Abstract

Background and aim

Human papillomavirus (HPV) testing has been recommended by the WHO as the first choice method in cervical cancer screening. So far, only a limited number of countries have implemented primary HPV testing, partly because of the assumed high costs of HPV testing. We assessed tender-based prices of HPV testing in Italy, where programmatic HPV-based screening has been implemented at the regional level.

Materials and methods

Procurement notices and awards, published between 2014 and December 2021, were retrieved from the European online platform for public procurement. The unit price per HPV test was calculated as the ratio of the contract award price and contract volume. The association between the unit price and contract volume, calendar year, number of offers, region’s per capita gross domestic product and population density was assessed by linear regression. Fractional polynomials were used to describe the association between the unit price and contract volume.

Results

We retrieved data from 29 procurement procedures. The median unit price per HPV test was €10.75, ranging from €4.30 to €204.80. The unit price was not higher than €5 for 6 out of 11 contract awards with a volume of at least 100,000 tests. After discarding two low-volume contracts with very high contract prices (€182.40 and €204.80), volume explained 86.5% of the variation in unit price. The unit price was not associated with other variables.

Conclusions

The Italian experience showed that the tender-based unit price of an HPV test is very low when procured at high volume, indicating that there is no reason for countries to further delay the implementation of HPV-based screening because of prohibitively high HPV testing costs.

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY

Health authorities purchase healthcare goods and services in bulk through a procedure called tendering that drives the price down as a result of price competition. A contract is made between the health authority and the supplier for a fixed price (i.e. tender-based price) for a certain amount of goods (i.e. contract volume) and a certain period. HPV testing for cervical cancer screening is subject to tendering and tender-based prices are important to inform about the costs associated with cervical screening. We collected public tender documents for HPV testing in Italian regions and calculated tender-based unit prices per HPV test. We found tender-based unit prices ranging from €4.30 and €204.80, with low prices for contracts with large volumes. In particular, the unit price per HPV test was not higher than €5 for the majority of contracts with a volume of at least 100,000 tests. This shows that the implementation of HPV-based screening does not lead to prohibitively high costs and may even lead to cost savings. Health authorities might collaborate in order to contract large volumes of HPV tests. Transparency around the prices of HPV testing as provided by this study is important to support health authorities when organizing a tender for the purchase of HPV tests.

Introduction

Human papillomavirus (HPV) testing is more effective in preventing cervical precancer and cancer, less labor intensive and less prone to quality problems than visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA) or cytology-based tests. HPV testing has been recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) as the primary screening method for cervical cancer prevention in all countries, including low- and middle-income countriesCitation1,Citation2. However, after nearly a decade from the first WHO recommendation, only a limited number of countries have implemented (organized) HPV-based screening programs using primary HPV testing either alone (e.g. Australia, Argentina, Italy, Malaysia, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Sweden, Turkey, UK) or in combination with cytology (e.g. US)Citation3–6.

The cost-effectiveness of HPV-based screening has been extensively shown in the literatureCitation7–9, but key concerns of stakeholders about introducing HPV screening remain in particular about high initial costs and high costs of test procurementCitation10–12. In fact, the list prices used in cost-effectiveness analyses often highlight the higher costs of HPV testing as compared to VIA or cytologyCitation13–15. To control healthcare costs, health authorities usually procure healthcare goods and services through a tendering procedure. Tendering is a public procurement procedure based on a competitive bidding process where the contract is granted to the supplier with the best bid depending on defined criteriaCitation16,Citation17.

In this report, we assessed and analyzed tender-based prices of HPV testing in a cervical cancer screening program, using Italy as a case study. Italy offers a unique possibility to study variables that may influence tender-based HPV test prices because i) Italy was the first country that approved implementation of HPV-based screening in 2014 after a decade of randomized and non-randomized pilot studiesCitation18, ii) Italy is implementing programmatic HPV-based screening at the regional level which means that several region-specific procurement documents are available, iii) procurement documents are publicly available through the European tender website (TED, ted.europa.eu). By collecting public procurements, it is possible to perform an assessment of tender-based prices of HPV testing after nearly a decade of regional HPV-based screening in Italy.

Methods

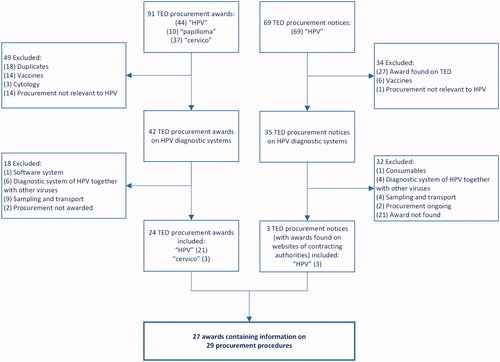

We conducted a search on the Tenders Electronic Daily (TED, ted.europa.eu), which is the online version of the ‘Supplement to the Official Journal of the European Union’ dedicated to European public procurementCitation19. We searched the platform’s archives for procurement award notices tendered in Italy up to 31st December 2021 using the search terms ‘HPV’, ‘papilloma’, and ‘cervico’ (Italian for ‘cervical’) (). We searched for general HPV tests (DNA or RNA) based on the principle of target amplification (i.e. polymerase chain reaction, PCR) or signal amplification. We only selected procurement awards for HPV diagnostic systems (i.e. HPV test only), because cervical sampling and transport are tendered separately.

Figure 1. Diagram of contract awards collection process for the unit prices of the HPV test. Abbreviations: HPV, human papillomavirus; TED, Tenders Electronic Daily.

The standardized procurement awards from the TED website usually stated the total end-value of the contract, reflecting the final agreement on the procurement of a specified volume, but not the contract volume. To retrieve the contract volume, we searched the website of the contracting authority for the procurement documents using the identification code, name and/or year of the contract. The contract volume was usually stated in one of the official documents containing technical specifications. In case we were unable to retrieve the contract volume, we contacted the person responsible for the tendering directly through e-mail or phone.

To minimize the chance of missing contract award notices, we repeated the search on the TED platform for procurement notices (instead of award notices) tendered up to 31st December 2021 using the search term ‘HPV’ (). When the procurement notice did not have a corresponding award on the TED platform, we searched the website of the contracting authority for the contract award using the identification code, name and/or year of the notice. A procurement notice was included only when the respective contract award could be located. All documents were checked in their original language (Italian). Details about the procurement notices and awards, including the TED publication number, can be found in the Supplementary Appendix (Table S1).

We stored information on the following parameters: the type of procedure (open or restricted); the number of offers received in the procurement procedure; the award selection criteria; the contractor; the calendar contract year; the duration of the contract; the total end-value of the contract (value added tax (VAT) excluded); and the contract volume, defined as the estimated number of tests for the entire duration of the contract. Additionally, we stored information on the type and intended use of the HPV test, i.e. DNA- or RNA-based, whether its use in cervical screening was explicitly stated, and whether genotyping was included in the contract. Besides, we obtained region-specific information from Eurostat on per capita gross domestic product (GDP) and population density in Italy in 2018Citation20.

The tender-based unit price was calculated by dividing the total end-value of the contract by the contract volume. The association between the unit price of the HPV test and volume was estimated by a fractional polynomial and uncertainty was represented by pointwise 99 percent confidence intervals. Multiple linear regression was applied to study the association between unit price of HPV test and contract volume, calendar year, number of offers, region’s GDP and region population density. Analyses were performed in Microsoft Excel 2016 and Stata/SE 14.1. For estimating the fractional polynomial, the STATA procedure fp was applied.

Results

The search on the European tender platform yielded a total of 91 procurement awards and 69 procurement notices (). We identified 27 awards for HPV diagnostic testing systems for which we were able to locate the contract award, either from the TED website (n = 24) or from the website of the contracting authority (n = 3). Two awards contained information on two different tenders so, altogether, we included 29 procurements for HPV testing performed in 15 Italian regions (). Procurements were done at different authority levels, for a single hospital, for the city or for the entire region. For five procurements we were unable to get information about the contract volume, leaving 24 procurements with complete information for calculation of the unit price of the HPV test. Of those, three procurements were awarded in 2014, three in 2015, one in 2017, seven in 2018, two in 2019, three in 2020, and five in 2021. Twenty out of the 25 procurements used quality and price as award selection criteria, and four used only the price criterion. The number of offers received in the procurement procedure ranged from one to three, and the duration of the contracts ranged from two to six years. Twenty-two out of the 24 procurements were for DNA-based HPV tests and two were for RNA-based HPV tests.

Table 1. Characteristics of the contract awards.

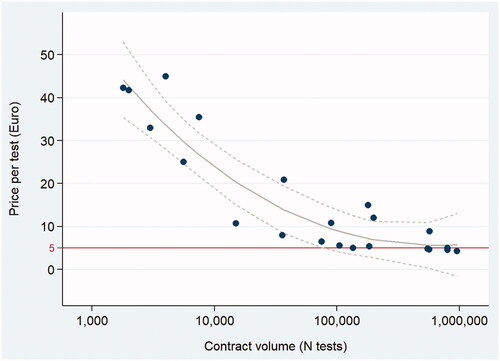

The median tender-based unit price per HPV test was €10.75, and prices ranged from €204.80 for a contract with a volume of 2,200 tests to €4.30 for a contract with a volume of 960,000 tests. There were two contracts with very high unit prices of €181.64 and €204.80 and low volumes of 2,000 and 2,200 respectively. All other contracts had unit prices below €45 and the median unit price was €9.78. In the subgroup of contracts that explicitly mentioned HPV testing as part of a regional cervical screening program, the median unit price was €5.45. In five contracts that explicitly mentioned genotyping on top of the positive/negative HPV test result, the median contract price was €41.76. Seventy-five percent (6 out of 8) low-volume tenders (contract volume ≤10,000) received only one offer, while 88 percent (14 out of 16) tenders with a contract volume >10,000 received two or three offers. Unit prices are plotted in by contract volume. The association between the unit price and volume was fitted by a linear regression model with a fractional polynomial of degree 2 (), which explained 86.5 percent of the variance in the unit price. None of the other contract parameters and region parameters was associated with a unit price after adjusting for contract volume. also illustrates that the unit price did not exceed €5 for six out of eleven contract awards with a contract volume of at least 100,000 tests.

Figure 2. Linear regression analysis of tender-based unit price per HPV test by contract volume. The fractional polynomial regression line with a 99 percent confidence interval is shown in grey and a reference line for a unit price of €5 is shown in red.

Two contract awards with very high unit prices (Cagliari 2018 unit price €204.80 and volume 2,200; Roma 2021 unit price €181.64 and volume 2,000) are not depicted in the plot. R-squared of the fractional polynomial regression model with degree 2 = 86.5 percent.

Discussion

By collecting public procurements, we were able to perform an assessment of tender-based prices of HPV testing after nearly a decade of regional HPV-based screening in Italy. We found that the unit price was strongly influenced by the contract volume (i.e. number of tests contracted for a pre-specified time period) and that six out of eleven contract awards with a volume of at least 100,000 tests had a tender-based unit price of the HPV test not exceeding €5.

In an early health technology assessment conducted in 2012, the reference price of an HPV test in the Italian screening program setting was estimated at €15 for a volume of 80,000Citation15. The same study indicated that HPV-based screening would lead to extra costs in the first round of screening, but that the program as a whole would remain cost-effective when shifting from eleven rounds of cytology screening to seven rounds of HPV screening. On the basis of the health technology assessment in 2012, a 2016 reportCitation21 advised regional public health authorities to use a provisional price of €10 for HPV testing. Our search revealed that half of the contract awards had tender-based prices which were at least two-thirds lower than the 2012 reference unit price and at least 50 percent lower than the 2016 provisional price level of €10. With such marked differences, formal cost-effectiveness analyses might even conclude that HPV-based screening is not only a cost-effective but also a cost-saving strategyCitation22. However, such conclusions can only be drawn after adjusting for the increase in follow-up diagnostic costs and treatment costs in the first round of HPV-based screening because of the lower specificity of HPV testing compared to cytologyCitation9,Citation15.

We found a very strong association between the procurement outcome and contract volume: at volumes above 100,000, more than half of the contracts had a unit price below or equal to €5 and at a volume close to 1 million, a unit price of €4.30 was observed. Increasing the contract volume gives public health authorities more bargaining power since the market becomes more interesting to manufacturers. Therefore, scaling up screening services, as suggested not only for high- but also for low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) Citation12, seems a feasible strategy for implementing HPV testing in a budget-neutral or even cost-saving way. The low HPV test prices achieved at high volumes further demonstrate that transparency in tender procedure outcomes does not increase contract prices. In some countries like the NetherlandsCitation23 and the UK, outcomes of tendering processes are not disclosed and one of the arguments is that it may lead to a higher contract award price. The low tender-based prices in Italy proves them wrong, supporting the idea that health authorities at the national and sub-national level should make contract awards publicly available. On the other hand, full disclosure of unit prices in high-income countries may allow companies to set a reference price for LMICCitation24,Citation25, but international efforts are in place to strengthen policies, promote transparency and joint procurement to support fair prices and enhance equal access to medicines and health technologies around the worldCitation26. Examples of international organizations that procure vaccines for LMIC are the GAVI alliance, PAHO, and UNICEFCitation27.

The use of tendering as public procedure for the procurement of healthcare goods/services is widespread knowledge, but assessment of tender-based prices of specific goods/services is not common in the literature. There is a small but growing literature on competitive bidding in healthcare, but it has mostly focused on the quality of the tendering process and the impact of tendering on the marketCitation17,Citation28. A few country-specific studies which report on the impact of tendering on prices include a study from Greece which showed that centralized tendering reduced the prices of healthcare goods by 57 percentCitation29, a study from South Africa which showed that tendering reduced the prices of medicines by at least 40 percentCitation30, and a recent US study which showed that competitive bidding reduced prices of healthcare goods by 45 percentCitation31.

The methodology in our study, which is the evaluation of tender-based prices by collecting public procurements, was previously used for the procurement of HPV vaccines in Italy and EuropeCitation32,Citation33. To our knowledge, our study estimated the level of tender-based prices for HPV testing from contract awards for the first time, although millions of HPV screening tests are conducted annually. Therefore, our study provides essential costing information. For formal cost-effectiveness analyses of HPV screening programs, the unit prices of the HPV tests need to be complemented with costs of sampling and transportation, consumables, personnel, and facilities. With respect to the costs of personnel and infrastructure, it can be noted that extensive PCR testing capacity, staffing expertise for testing and the use of existing infrastructures, deployed all over the world during the COVID-19 pandemic, represent opportunities for cervical cancer screening in both high-income countries and LMICCitation34,Citation35.

We chose Italy for our case study because it is one of the first countries in the world that initiated implementation of primary HPV screening and procurement of HPV tests is done at the regional level. Reported HPV prevalences in Italian provinces lie between 6.3% and 8.7%, which are similar to that of other regions/countries in Europe where HPV-based screening has been implemented recentlyCitation36. We believe that the outcome of our study is generalizable to other settings because, besides contract volume, we did not find other variables that were associated with unit HPV test price. Specifically, we found no association between the unit price and calendar year and low prices were observed throughout the entire period 2014–2021. Therefore, as a future drop in the price of HPV tests is not to be expected without further increasing contract volumes, there is no reason for countries to delay implementation of HPV-based screening. Notably, the previously published analysis on tender-based prices of HPV vaccines showed that the price per dose strongly decreased with calendar year and this may have motivated countries to postpone the implementation of HPV vaccination until prices had plateaued, which happened about a decade after the introduction of HPV vaccination in 2007Citation33.

A limitation of our study was that we were not able to compare the price of HPV DNA testing to HPV mRNA testing, the latter attracting considerable interest because of the relatively high specificityCitation37,Citation38. Our search identified only two RNA-based HPV tests with contract volumes of 2,000 and 180,000. The mRNA test contract with a volume of 180,000 had a unit price of €15, which lies about €10 above the estimated price-volume curve (), but more contracts are needed to make a reliable comparison. Another limitation of our study is that we only relied on the European TED website as our primary source of information, meaning that we did not consider procurements that did not fit our search criteria or that were registered outside of the European platform. Italy was used as a case study and our findings may not be generalizable to all countries. In particular, the income level, represented by the GDP, may have an effect on procurement outcomes as shown for HPV vaccinesCitation33 although we did not find an effect of GDP in our study. Besides, not all regions in Italy have fully implemented HPV-based screening, meaning that the total number of HPV tests needed will be higher in the future and, if health authorities work together, the purchase costs per region may further decrease as a consequence of increasing contract volumes.

In conclusion, we showed that the tender-based price of an HPV test can be as low as 4 to 5 euros, suggesting that implementation of HPV-based screening does not lead to extra costs in the first round and would be cost-saving in subsequent rounds. Enhancing transparency by reporting tender-based unit prices may help national health authorities to procure HPV tests for cervical cancer screening at a cost-based price. Besides, in countries without primary HPV screening, it can support health authorities in their decision to implement primary HPV screening. Our analyses and results can be used to infer on healthcare goods and services besides HPV testing for cervical cancer screening. Assessment of tender-based prices is possible by collecting public procurements, where these are present. Public availability of such documents stimulates transparency around tendering procedures and costs associated with healthcare. The association between tender-based prices and contract volume indicates that purchasing power is higher when larger quantities are contracted, thus centralized tendering is preferable to local tendering and the formation of alliances for pooled tendering should be considered whenever possible.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This work was supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (RISCC, grant agreement number 847845). The funders had no role in the identification, design, conduct, reporting, and interpretation of the analysis.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

FI and JB had financial support from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (RISCC, grant agreement number 847845) for the submitted work. No other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

FI and JB conceived and designed the study, FI collected the data, FI and JB conducted the analysis, drafted and revised the manuscript.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (23.3 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the people responsible for the procurement procedures who very kindly helped us retrieving information on the contract agreements.

Data availability statement

This study is based on procurement notices and awards publicly available on the European tender platform TED (ted.europa.eu)Citation19. TED procurement publication numbers can be found on the Supplementary Appendix (Supplementary Table 1).

References

- WHO guideline for screening and treatment of cervical pre-cancer lesions for cervical cancer prevention, second edition; 2021. [cited 2021 Dec 17]. Available from https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240030824.

- Bouvard V, Wentzensen N, Mackie A, et al. The IARC perspective on cervical cancer screening. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(20):762–1918.

- Maver PJ, Poljak M. Primary HPV-based cervical cancer screening in Europe: implementation status, challenges, and future plans. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26(5):579–583.

- Guidelines for primary HPV testing for cervical cancer screening in Malaysia. Family Health Development Division, Ministry of Health Malaysia. 2019. [cited 2021 Dec 20]. Available from https://www.ogsm.org.my/docs/GUIDELINES%20FOR%20PRIMARY%20HPV%20TESTING%20FOR%20CERVICAL%20CANCER%20SCREENING%20IN%20MALAYSIA.pdf.

- About the National Cervical Screening Program. Department of Health, Australian Governement. [cited 2021 Dec 20]. Available from https://www.health.gov.au/initiatives-and-programs/national-cervical-screening-program/about-the-national-cervical-screening-program.

- Fontham ETH, Wolf AMD, Church TR, et al. Cervical cancer screening for individuals at average risk: 2020 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA A Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(5):321–346.

- Goldie SJ, Kim JJ, Wright TC. Cost-effectiveness of human papillomavirus DNA testing for cervical cancer screening in women aged 30 years or more. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103(4):619–631.

- Kim JJ, Wright TC, Goldie SJ. Cost-effectiveness of human papillomavirus DNA testing in the United Kingdom, The Netherlands, France, and Italy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(12):888–895.

- Vijayaraghavan A, Efrusy MB, Mayrand MH, et al. Cost-effectiveness of high-risk human papillomavirus testing for cervical cancer screening in Québec, Canada. Can J Public Health. 2010;101(3):220–225.

- Felix JC, Lacey MJ, Miller JD, et al. The clinical and economic benefits of co-testing versus primary HPV testing for cervical cancer screening: a modeling analysis. J Womens Health. 2016;25(6):606–616.

- Petry KU, Barth C, Wasem J, et al. A model to evaluate the costs and clinical effectiveness of human papilloma virus screening compared with Annual Papanicolaou Cytology in Germany. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017;212:132–139.

- Tsu VD, Njama-Meya D, Lim J, et al. Opportunities and challenges for introducing HPV testing for cervical cancer screening in Sub-Saharan Africa. Prev Med. 2018;114:205–208.

- Goldie SJ, Gaffikin L, Goldhaber-Fiebert JD, et al. Cost-effectiveness of cervical-cancer screening in five developing countries. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(20):2158–2168.

- Darus N, Chandriah H, Lajis R. Health Technology Assessment Report: HPV DNA-based screening test for cervical cancer. Ministry of Health Malaysia. 2011. [cited 2021 Dec 20]. Available from https://www.moh.gov.my/moh/resources/auto%20download%20images/587f12c7011bb.pdf.

- Ronco G, Biggeri A, Confortini M, et al. Health technology assessment report: HPV DNA based primary screening for cervical cancer precursors. Epidemiol Prev. 2012;36(3–4 Suppl 1):e1–72.

- Leopold C, Habl C, Vogler S. Tendering of pharmaceuticals in EU Member States and EEA countries: results from the country survey; 2008. [cited 2021 Dec 17]. Available from http://whocc.goeg.at/Literaturliste/Dokumente/BooksReports/Final_Report_Tendering_June_08.pdf.

- Maniadakis N, Holtorf AP, Otávio Corrêa J, et al. Shaping pharmaceutical tenders for effectiveness and sustainability in countries with expanding healthcare coverage. Appl Health Econ Health Policy; 2018;16(5):591–607.

- Ronco G, Giorgi-Rossi P, Carozzi F, et al. Efficacy of human papillomavirus testing for the detection of invasive cervical cancers and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(3):249–257.

- Ted -Tender electronic daily. Supplement to the Official Journal. Available from: http://www.ted.europa.eu.

- Eurostat - The statistical office of the European Union. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat.

- Giorgi Rossi P, Naldoni C, Di Stefano F, et al. Report MIDDIR – Methods for investments/disinvestments and distribution of health technologies in Italian Regions. Chapter 5. 2016. [cited 2021 Dec 20]. Available from: https://www.cpo.it/workspace/files/report-middir-aprile2016-571a18a7556a9.pdf.

- Mandelblatt JS, Lawrence WF, Womack SM, et al. Benefits and costs of using HPV testing to screen for cervical cancer. Jama. 2002;287(18):2372–2381.

- den Ambtman A, Knoben J, van den Hurk D, et al. Analysing actual prices of medical products: a cross-sectional survey of Dutch Hospitals. BMJ Open. 2020;10(2):e035174.

- Kaló Z, Annemans L, Garrison LP. Differential pricing of new pharmaceuticals in lower income European Countries. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2013;13(6):735–741.

- Shaw B, Mestre-Ferrandiz J. Talkin' about a resolution: issues in the push for greater transparency of medicine prices. Pharmacoeconomics. 2020;38(2):125–134.

- Perehudoff K, Mara K, Hoen E. WHO Health Evidence Network Synthesis Report, No. 73 – What is the evidence on legal measures to improve the transparency of markets for medicines, vaccines and other health products (World Health Assembly resolution WHA72.8); 2021.

- Hussain R, Bukhari NI, Ur Rehman A, et al. Vaccine prices: a systematic review of literature. Vaccines. 2020;8(4):629.

- Barbier L, Simoens S, Soontjens C, et al. Off-Patent biologicals and biosimilars tendering in Europe-a proposal towards more sustainable practices. Pharmaceuticals. 2021;14(6):499.

- Kastanioti C, Kontodimopoulos N, Stasinopoulos D, et al. Public procurement of health technologies in Greece in an era of economic crisis. Health Policy. 2013;109(1):7–13.

- Wouters OJ, Sandberg DM, Pillay A, et al. The impact of pharmaceutical tendering on prices and market concentration in South Africa over a 14-year period. Soc Sci Med. 2019;220:362–370.

- Ji Y. Can Competitive Bidding Work in Health Care? Evidence from Medicare Durable Medical Equipment. Harvard University. 2021. [cited 2022 May 21]. Available from: https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/yunan/files/dme.pdf.

- Garattini L, van de Vooren K, Curto A. Pricing human papillomavirus vaccines: lessons from Italy. Pharmacoeconomics. 2012;30(3):213–217.

- Qendri V, Bogaards JA, Berkhof J. Pricing of HPV vaccines in European tender-based settings. Eur J Health Econ. 2019;20(2):271–280.

- Woo YL, Gravitt P, Khor SK, et al. Accelerating action on cervical screening in Lower- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs) post COVID-19 era. Prev Med. 2021;144:106294.

- Vorsters A, Bosch FX, Poljak M, et al. HPV prevention and control – The way forward. Prev Med. 2022;156:106960.

- IARC 2022. Cervical cancer screening. IARC Handb Cancer Prev. 18:1–456. [cited 2022 May 21]. Available from https://publications.iarc.fr/604.

- Iftner T, Becker S, Neis KJ, et al. Head-to-Head comparison of the RNA-Based aptima human papillomavirus (HPV) assay and the DNA-Based hybrid capture 2 HPV test in a routine screening population of women aged 30 to 60 years in Germany. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53(8):2509–2516.

- Maggino T, Sciarrone R, Murer B, et al. Screening women for cervical cancer carcinoma with a HPV mRNA test: first results from the Venice Pilot Program. Br J Cancer. 2016;115(5):525–532.