Abstract

The current use of economic evidence in the decision-making process in the US is increasing. Meta-analysis of economic evaluations (MAEE) has gained recognition in recent years and can support decision-making at the global level or for countries with resource constraints. The focus of this article is to demonstrate how MAEE may contribute to the decision-making process in the US healthcare system. We demonstrated that MAEE can provide an efficient mechanism to quantitatively summarize cost-effectiveness findings based on all existing studies from the US answering the same question across different assumptions. This sort of evidence is important for US policymakers to support policy decision-making. MAEE methods can streamline the process of reviewing complex economic models and their findings, which has been previously reported by stakeholders as a barrier to the use of economic evidence in decision-making in the US. However, the currently proposed method may not fully address the issue of heterogeneity observed among MAEEs. There is a critical need to explore sources of heterogeneity and develop a standardized approach to handle it to improve the efficiency and acceptability of future MAEEs.

Introduction

Since the 1990s, the number of economic evaluations (EEs), such as cost-effectiveness or cost-utility analyses (CEA/CUA), has grown considerably, involving a wide range of diseases and interventionsCitation1. Although the evidence on the cost-effectiveness of health interventions is increasingly being used in healthcare decision-making globally, the extent to which this evidence influences decision varies by country. Many public and private organizations in developed countries have formally adopted economic evidence to inform healthcare policy and reimbursement decisionsCitation1. Meanwhile, considering economic evidence in healthcare decisions has long been viewed as unattractive in the United States (US). One exception is the use of economic evidence by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) to inform national recommendations on immunization policyCitation2.

Recently, a growing concern about rising costs and inefficient health care spending has led to greater use of economic evidence in public and nonprofit organizations’ health care decisions in the US. For instance, the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER) Group, a US-based independent, nonprofit organization, generates drug value assessment reports to provide a reasonable benchmark with which to assess drug prices set by manufacturers and assess the success of public and private strategies designed to place downward pressure on those pricesCitation3. A drug value assessment report is a systematic review of a drug’s comparative clinical effectiveness in comparison to other drug treatment options, combined with an analysis of its long-term cost-effectiveness versus those other optionsCitation3. Recently, such reports are increasingly being used by state Medicaid programs, many of which have deployed them for prior authorization elements of coverage decisionsCitation3. The US Department of Veterans Affairs is making greater use of them in price negotiations with manufacturersCitation3. Private insurers and pharmacy benefit managers have started using them in their coverage processes as a guide to fair pricing and fair accessCitation3,Citation4. The International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) special task force on the US value assessment frameworks proposed greater use of economic evidence in payer’s decision-making process in order to better serve the interest of the plan members and patients who they representCitation5. Recent surveys of US payers, including decision-makers in managed care, pharmacy benefit management organizations, hospitals, and others, revealed that 59% of respondents or their organizations had used ICER's assessments in formulary decisionsCitation4. Moreover, medical professional societies and other organizations also initiated to develop practice guidelines that take economic evidence into account (e.g. American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association (ACC–AHA), the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), etc.)Citation1. It is clear from the evidence gathered to date that economic evidence can be a valuable supplemental tool in the decision-making process in the US. The current use of economic evidence is increasing, and stakeholders especially payers are using them in a number of different waysCitation4,Citation6. However, stakeholders observed several challenges such as reviewing complex economic models and their findings, the risk of potential bias, and other concerns that have been discussed in greater detail elsewhereCitation4,Citation5,Citation7,Citation8, while employing economic evidence in decision-making in the US.

Why meta-analysis of economic evaluations?

The use of EEs to inform decision-making has rapidly increased in recent decades across the world. Decision-makers are confronted with often unmanageable amounts of information and conflicting findings from such evaluations. Systematic reviews of economic evaluations (SREEs) can provide an efficient mechanism to synthesize existing cost-effectiveness evidence to answer a specific questionCitation9; the number of such evaluations is steadily increasing. However, SREEs provided only a descriptive and qualitative summary of evidence. The Cochrane handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions discussed that there are no agreed methods for pooling estimates of cost-effectiveness but did not expand on the issuesCitation10. Later, Crespo et al. 2014 suggested statistical methods for performing meta-analysis of economic evaluation studies (MAEE) using comparative efficiency research (COMER)Citation11. The incremental net benefit (INB) is used as the outcome of interest in this approach, rather than the more commonly used incremental cost-effectiveness ratio as seen in CEAs. Our research teams have recently further modified their methods and devised a step-by-step data harmonization to ease in performing MAEE effectivelyCitation12. A detailed methodology for performing MAEE that covers all aspects has been published elsewhereCitation12. The Immunization and Vaccine-related Implementation Research Advisory Committee (IVIR-AC)-World Health Organization (March 2021) agrees that the quantitative evidence generated from MAEEs was useful to support clear policy recommendations and can facilitate decision-making in resource-strained settings where context-specific EEs are not availableCitation13. Instead of using MAEEs to support decision-making at the global level or for countries with similar resource constraints, the rest of this article uses examples of MAEEs to describe the potential application of MAEEs in the US healthcare setting.

The potential application of MAEE in the US healthcare setting

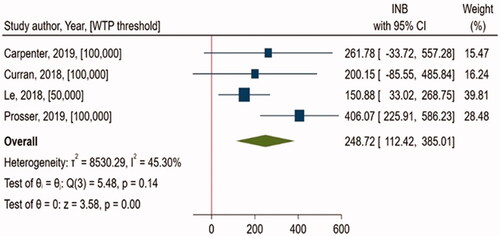

The first example demonstrated the findings from a MAEE comparing the cost-effectiveness of Recombinant Zoster Vaccine (RZV) vs. no vaccination (NoV) using four studiesCitation14–17 conducted from a societal perspective in the US (). All studies were CEAs reporting cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY). Previously, CDC conducted a CEA comparing RZV, Zoster Vaccine Live (ZVL), or NoV from a societal perspective, using time horizon of lifetimeCitation14. It estimated that vaccination with RZV, compared with NoV, was cost-effective for immunocompetent adults aged ≥50 years. Currently, the ACIP Herpes Zoster Vaccines Work Group is recommending RZV for immunocompetent adults aged ≥50 years for the prevention of Herpes ZosterCitation2. We included three more CEAs in this MAEECitation15–17, one of which was a manufacturer-sponsored analysisCitation16. The primary outcome of interest was INB. A positive INB favors the intervention as cost-effective, whereas a negative INB favors the comparator with the intervention being not cost-effective. In this meta-analysis, quantitative synthesis of economic evidence indicated that RZV is significantly cost-effective compared to NoV (pooled INB, $248.72 (95% CI, $112.42, $385.01), I2 = 45.3%), which is consistent with ACIP's recommendation which supports the use of RZVCitation2. MAEE methodology uses a systematic review process to identify comprehensively all studies for a specific focused question, appraise the model and assumptions of the included studies, and scrutinize their overall qualityCitation12. This streamlines the process of reviewing complex economic models and their findings, which has been previously cited by payersCitation4,Citation8 and other stakeholdersCitation7 as a barrier to using economic evidence in decision-making in the US. In addition, this process may also enable to generate a collection of study strata with similar characteristics, for example, subgroup of population, perspective, assumptions of EE model and clinical settings, study quality, funding, etc., allowing further analyses such as sensitivity or subgroup analyses to observe how findings varied across different conditions.

Generally, CEAs that address the same question are likely to generate varying or conflicting findings, which might be due to the substantial variability in assumptions (such as willingness-to-pay (WTP) threshold, perspective, model assumptions, etc.) employed in their analysisCitation18. As shown in this example, four studies that addressed the same question generated somewhat varied results ( and ). Two studies (Curran, 2018; Carpenter, 2019) that used a willingness-to-pay (WTP) threshold of $100,000/QALY failed to attain statistical significance, but one study (Prosser, 2019) with a threshold of $100,000/QALY and another (Le, 2018) with a threshold of $50,000/QALY did. MAEE can provide an efficient mechanism to quantitatively summarize cost-effectiveness findings based on all existing studies from the US answering the same question across different assumptions. This sort of evidence might be important for US policymakers who want to endorse a clear policy recommendation. Furthermore, as shown in additional analyses can be performed by applying a single WTP threshold value across individual studies, thus minimizing the variability in WTP threshold across studies and deriving pooled INB from MAEE when all studies used the same WTP threshold. WTP threshold is used as a cut-off for determining whether an intervention is cost-effective in CEAs. Even though there was no specific threshold explicitly stated, a range of $50,000–150,000 has been used in the context of the US healthcare systemCitation1. In this example, additional analyses illustrate that RZV is cost-effective in all acceptable threshold ranges in the US, including $50,000, with no heterogeneity (), demonstrating the value of this intervention. Identifying the cutoff threshold value at which an intervention would be cost-effective is a piece of valuable information that may support decision-making, and MAEE can offer such evidence using this approach.

Table 1. The calculated INB values and MAEE results when WTP threshold cut-offs were varied and applied uniformly across studies for cost-effectiveness of Recombinant Zoster Vaccine (RZV) vs. no vaccination (NoV) of four studies conducted from a societal perspective in the US.

Heterogeneity: a potential challenge in MAEE

Although we discussed several possible MAEE applications in the US healthcare setting, one of the major methodological challenges, i.e. the large heterogeneity observed in MAEEsCitation12, has yet to be fully addressed. There are many sources that might contribute to heterogeneity while performing MAEE, including study characteristics (such as setting, WTP threshold, perspective, funding source) and methodological characteristics (such as time horizon, data source, model type, input parameters, and assumptions)Citation18. As an example, EEs that utilized the same meta-analysis of clinical effectiveness as an input parameter in the model are more likely to have similar cost-effectiveness findings, allowing the results to be pooled with minimal heterogeneity. It is important to emphasize that because we are pooling findings across those EEs, this is not directly related to the issue of double counting as seen in traditional meta-analysis of clinical effectiveness. Instead, this is a part that would explain potential differences in findings across studies. The larger the differences in input parameters and assumptions used across EEs, the more likely substantial heterogeneity in MAEE would be observed. As shown in the previous example, we observed a high level of heterogeneity of 45.3% in the main analysis (). However, when we used a single WTP threshold value across individual studies while performing MAEE, heterogeneity is reduced to zero in all scenarios as shown in . It suggests that variation in the WTP threshold observed in individual studies might be one source of heterogeneity. provided findings on heterogeneity from MAEEs comparing Direct Oral Anticoagulants (DOACs) (i.e. dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban) versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation in the US settingCitation19. With the exception of the comparison between rivaroxaban vs warfarin, we found significant heterogeneity in all other comparisons. As shown in , when we standardized the WTP threshold across individual studies into a single value, we found only a minimal change from heterogeneity observed in the main analysis. As an example, MAEE comparing Dabigatran vs. warfarin, demonstrated substantial level of heterogeneity (I2 = 89.28%) in the primary analysis (). Among 9 studies included in this MAEE, three were manufacturer’s sponsored economic analysesCitation19. It is expected that findings in cost-effectiveness analyses may vary by funding source and there is likelihood of observing high level of heterogeneity when we pool these studies. The potential underlying reason for this phenomenon is the assumptions applied to the economic evaluations that vary by funding source. According to meta-regression, funding source partially explains heterogeneity observed in this MAEECitation19. This clearly demonstrates that, in many instances, other factors, in addition to WTP, might contribute to heterogeneity. This indicates a strong need to explore other drivers that may be a potential cause of heterogeneity.

Table 2. The changes in the magnitude of heterogeneity (I2) compared to the main analysis when WTP threshold cut-offs were varied and applied uniformly across studies for the cost-effectiveness of Direct Oral Anticoagulants in the US.

Conclusions

The current use of economic evidence in the decision-making process in the US is increasing. We believe that MAEE makes SREEs more meaningful and can provide an efficient mechanism to quantitatively summarize cost-effectiveness findings based on all existing studies from the US answering the same question across different assumptions. There is a critical need to explore sources of heterogeneity seen among MAEEs and to develop a standardized approach to handle it.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of financial/other relationship

The authors declare that they have no known conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this article.

A reviewer on this manuscript has disclosed that they are an employee of PRECISIONheor, a health economics consulting firm that provides services to pharmaceutical companies. I also hold equity in our parent company, Precision Medicine Group. The other peer reviewers on this manuscript have no other relevant financial relationships or otherwise to disclose.

Author contributions

SKV, AT, and NC designed and drafted the article.

SKV and SS performed data preparation and analysis.

Code availability

The data analysis file is available from the corresponding author upon request.

Consent for publication

All authors approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Acknowledgements

None stated.

Data availability statement

All data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

- Kim DD, Basu A. How does cost-effectiveness analysis inform health care decisions? AMA J Ethics. 2021;23(8):750–647.

- Dooling KL. Recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices for use of Herpes Zoster Vaccines. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67.

- Pearson SD, Emond SK. How independent assessment of drug value can help states. 2022; [cited 2022 May 23]. Available from: https://icer.org/news-insights/commentaries/how-independent-assessment-of-drug-value-can-help-states/.

- Lising A, Drummond M, Barry M, et al. Payers’ use of independent reports in decision making – will there be an ICER effect?. Value Outcomes Spotlight. 2017. https://www.ispor.org/publications/journals/value-outcomes-spotlight/abstract/march-april-2017/payers-use-of-independent-reports-in-decision-making-will-there-be-an-icer-effect.

- Garrison LP, Neumann PJ, Willke RJ, et al. A health economics approach to US value assessment frameworks-summary and recommendations of the ISPOR special task force report. Value Health. 2018;21(2):161–165.

- Fazio L, Rosner A, Drummond M. How do U.S. payers use economic models submitted by life sciences organizations? Value Outcomes Spotlight. 2016;2(2):18–21.

- Richardson JS, Messonnier ML, Prosser LA. Preferences for health economics presentations among vaccine policymakers and researchers. Vaccine. 2018;36(43):6416–6423.

- Biskupiak J, Oderda G, Brixner D, et al. Payer perceptions on the use of economic models in oncology decision making. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2021;27(11):1560–1567.

- van Mastrigt GAPG, Hiligsmann M, Arts JJC, et al. How to prepare a systematic review of economic evaluations for informing evidence-based healthcare decisions: a five-step approach (part 1/3). Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2016;16(6):689–704.

- Higgins JPT, Green S (Editors). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.1.0 [Updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.Handbook.Cochrane.Org.

- Crespo C, Monleon A, Díaz W, et al. Comparative efficiency research (COMER): meta-analysis of cost-effectiveness studies. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14(1):139.

- Bagepally BS, Chaikledkaew U, Chaiyakunapruk N, et al. Meta-analysis of economic evaluation studies: data harmonisation and methodological issues. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):202.

- World Health Organization. Meeting of the immunization and vaccine-related Implementation Research Advisory Committee (IVIR-AC). 2021;96(17):133–143.

- Prosser LA, Harpaz R, Rose AM, et al. A cost-effectiveness analysis of vaccination for prevention of Herpes Zoster and related complications: input for national recommendations. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170(6):380–388.

- Carpenter CF, Aljassem A, Stassinopoulos J, et al. A cost-effectiveness analysis of an adjuvanted subunit vaccine for the prevention of Herpes Zoster and post-herpetic Neuralgia. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019;6(7):ofz219.

- Curran D, Patterson BJ, Van Oorschot D, et al. Cost-effectiveness of an adjuvanted recombinant zoster vaccine in older adults in the United States who have been previously vaccinated with zoster vaccine live. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(4):765–771.

- Le P, Rothberg MB. Cost effectiveness of a shingles vaccine Booster for currently vaccinated adults in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2017;53(6):829–836.

- Shields GE, Elvidge J. Challenges in synthesising cost-effectiveness estimates. Syst Rev. 2020;9(1):289.

- Noviyani R, Youngkong S, Nathisuwan S, et al. Economic evaluation of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) versus vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Bmj EBM. 2021;2021:bmjebm-2020-111634.