Abstract

Aims

Pembrolizumab, as monotherapy in first-line recurrent or metastatic (R/M) head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) with a combined positive score (CPS) ≥1 and in combination with platinum and 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) in the overall R/M HNSCC population, received US FDA approval based on the KEYNOTE-048 trial. Using public drug prices, from a US payer perspective, we evaluated the cost-effectiveness of each pembrolizumab regimen vs. cetuximab + platinum+5-FU (EXTREME regimen, trial comparator), cisplatin + docetaxel + cetuximab (TPEx regimen), cisplatin + paclitaxel, and platinum+5-FU.

Methods

A three-state partitioned-survival model was used to project costs and outcomes over 20 years with 3% annual discounting. Progression-free and overall survival were modeled using long-term extrapolation of KEYNOTE-048 data and, for alternative comparators, data from a network meta-analysis was used. Time-on-treatment was derived from KEYNOTE-048 or approximated using network meta-analysis progression-free survival estimates. Costs included first-line and subsequent treatments, disease management, adverse events, and terminal care costs. Utilities were derived from the KEYNOTE-048 Euro-QoL five-dimension data and using a US algorithm.

Results

In the CPS ≥1 R/M HNSCC population, pembrolizumab monotherapy was dominant vs. EXTREME and TPEx regimens, and cost-effective (at $100,000/QALY threshold) vs. platinum+5-FU ($86,827/QALY) and cisplatin + paclitaxel ($81,473/QALY). Pembrolizumab combination therapy in the overall R/M HNSCC population was dominant vs. TPEx regimen, and cost-effective vs. EXTREME regimen ($1769/QALY), platinum+5-FU ($81,989/QALY), and cisplatin + paclitaxel ($89,505/QALY). Sensitivity analyses showed a high cost-effectiveness probability for pembrolizumab at the $100,000/QALY threshold.

Conclusions

First-line pembrolizumab monotherapy in patients with CPS ≥1, and pembrolizumab combination therapy in the overall R/M HNSCC population is cost-effective from the perspective of the US payers.

Introduction

Head and neck cancer encompasses tumors occurring in the region of the head and neck, including the oral cavity, nasal cavity, larynx, pharynx, paranasal sinuses, and salivary glandsCitation1. Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) accounts for roughly 90% of these cancers and refers specifically to tumors arising from the mucosa of the upper aero-digestive tractCitation2. A global incidence of 931,931 cases was estimated in 2020, including 58,864 cases from the United States (US)Citation3. According to the American Cancer Society (ACS), the incidence of oral cavity, pharynx, and larynx cancers will be 66,630 cases in 2021Citation4.

A minority of patients with HNSCC are initially diagnosed with metastatic disease (3.7%)Citation5. Most patients are diagnosed with locoregionally advanced disease (stage III-IVB) and receive chemotherapy primarily with platinum-based regimens, with or without surgery or radiationCitation6–8. However, many of these patients are at high risk of disease recurrence, with the 5-year risk ranging between roughly 50 and 60%Citation9–11. For patients with recurrent or metastatic (R/M) HNSCC, systemic therapy is used as palliative treatment, but treatment options have been limited. Historically, for patients with R/M HNSCC, platinum-based chemotherapy in combination with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), a taxane, or cetuximab has been the standard first-line treatmentCitation12–15.

Recently, PD-1 inhibitors have demonstrated effective antitumor activity with manageable safety in patients with R/M HNSCCCitation16–20. In phase III KEYNOTE-048 trial, the efficacy and safety of pembrolizumab monotherapy and pembrolizumab in combination with platinum+5-fluorouracil (5-FU) were compared with cetuximab in combination with platinum+5-FU (EXTREME regimen) in previously untreated R/M HNSCC patientsCitation19. Compared with the EXTREME regimen, the OS improved with pembrolizumab monotherapy in participants whose tumors express PD-L1 combined positive score (CPS) ≥1 (HR, 0.74; 95% CI: 0.61, 0.90), and with pembrolizumab in combination with platinum and 5-FU (pembrolizumab combination therapy) in the overall R/M HNSCC population (HR, 0.72; 95% CI: 0.60, 0.87). Pembrolizumab demonstrated a manageable safety profile compared with the EXTREME regimen; the incidence of grade ≥3 adverse events (AEs) was favorable with pembrolizumab monotherapy and similar with pembrolizumab combination therapy. On 10 June 2019, the FDA approved pembrolizumab monotherapy in patients with CPS ≥1 and pembrolizumab combination therapy in the overall population for the first-line treatment of R/M HNSCCCitation21. Subsequently, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) treatment guidelines included pembrolizumab as a preferred first-line option in R/M HNSCCCitation6. Following treatment with immunotherapy, the patient may receive subsequent treatment with a taxane or methotrexane and/or cetuximab, or best supportive careCitation22,Citation23.

Increasing healthcare expenditures require decision-makers to assess the value and cost-effectiveness of pembrolizumab. In the US, managed care organizations rely on clinical efficacy, safety, and cost data to develop evidence-based treatment pathways to ensure high-value cancer treatments are used in clinical practiceCitation24,Citation25. As such, there are limited data available on the cost-effectiveness of first-line pembrolizumab for R/M HNSCCCitation26–28. We took a US payer perspective to estimate the lifetime costs and health outcomes of pembrolizumab vs. the EXTREME regimen as first-line treatment for R/M HNSCC, utilizing patient-level data from the KEYNOTE-048 study (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02358031). The cost-effectiveness of pembrolizumab was also compared with other commonly used first-line R/M HNSCC treatments including cisplatin + docetaxel +cetuximab (TPEx regimen), cisplatin + paclitaxel, and platinum+5-FU utilizing results form a network meta-analysis (NMA)Citation29,Citation30.

Methods

Population

The economic evaluation was conducted in the FDA-approved populationCitation31. Baseline patient characteristics were obtained from the US enrolled patient subgroup across all arms in the KEYNOTE-048 intent-to-treat trial population. On average, patients were 62.3 years, with a mean weight of 73.8 kg and a mean body surface area (BSA) of 1.87 m2. Females represented 15.3% of the populationCitation32. The KEYNOTE-048 study protocol and all amendments were approved by the appropriate ethics committee at each centre. The study was done in accordance with the protocol, its amendments, and standards of Good Clinical Practice. All participants provided written informed consent before enrolmentCitation19.

Model structure

In accordance with the model structure used in the United Kingdom National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) health technology appraisals of cetuximab and of nivolumab for treating RM/HNSCC, we modeled the effects of treatments in terms of progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS)Citation33–35 from the KEYNOTE-048 trialCitation19. The model health states (progression-free, progressed-disease, and death) are mutually exclusive and associated with variations in quality of life and resource utilization outcomes.

We used a partitioned-survival modelCitation36. Patients enter the progression-free health state and receive treatment with pembrolizumab or a comparator regimen. Following each weekly cycle, patients remain within the same health state, or transition from the progression-free to the progressed-disease state, or die. Costs and outcomes were evaluated over 20 years, which was assumed as a reasonable lifetime time horizon for this population during which most deaths are expected to occur. The model used weekly cycles to incorporate different treatment schedules to allow sufficient precision to assess costs and outcomes. Simpson’s within-cycle correction was applied. For drug acquisition and their administration, however, costs were ascribed at the beginning of each treatment cycle to reflect the timing of cost occurrence more accuratelyCitation37.

Progression-free survival and overall survival

The final KEYNOTE-048 trial data cut-off, 25 February 2019, with a median follow-up of 11.5, 13.0, and 10.7 months in the pembrolizumab monotherapy, pembrolizumab combination therapy, and EXTREME regimen therapy group, respectively, was used to inform the analysisCitation32. For projecting long-term PFS and OS, Kaplan-Meier PFS and OS curves from the KEYNOTE-048 trial were used until a specific time cut-off, and thereafter parametric survival functions were used to fit the dataCitation38. The extrapolation fits were selected based on goodness of fit Akaike information criteria (AIC) and Bayesian information criteria (BIC) and visual inspection. For PFS, the 52-week cut-off point suggested by the Chow testCitation39 was used as it allowed for plausible long-term extrapolations when using the exponential curve beyond this time. Similarly, for OS, the 80-week cut-off was suggested by the Chow test, allowing for plausible long-term extrapolations when using the log-logistic functions among patients with CPS ≥1 and log-normal functions in the overall R/M HNSCC population.

For non-trial comparators, OS and PFS were obtained using time-varying hazard ratios relative to pembrolizumab based upon fractional polynomial NMACitation29,Citation30 (). For the NMA, a systematic literature review (SLR) was conducted to identify randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating the efficacy and safety outcomes of first-line systemic treatments in R/M HNSCC patients ineligible for curative treatment (i.e. surgery or radiation). Furthermore, included RCTs required a minimum treatment-free period of at least 6 months before study entry in the primary analyses and at least 3 months as secondary analyses. The final NMA network for OS and PFS outcomes included the KEYNOTE-048 trial and five other trials in the primary analysesCitation12–15,Citation19,Citation40, and three additional trials in the secondary analysesCitation41–43.

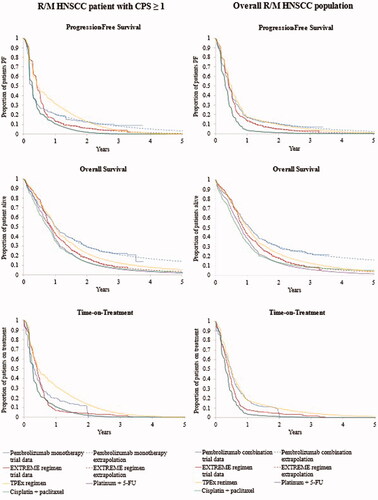

Figure 1. Long-term survival and time-on-treatment extrapolations for pembrolizumab regimens and comparators in patients with CPS ≥1 (left column) and in overall R/M HNSCC population (right column). Abbreviations. CPS, combined positive score; EXTREME regimen, Cetuximab + platinum + 5-Fluorouacil; KM, Kaplan-Meier; OS, overall survival; PF, progression-free; PFS, progression-free survival; TPEx regimen, Cisplatin + docetaxel + cetuximab; 5-FU, 5-fluorouracil.

Treatment-related adverse events

Hospital-related costs and disutilities were ascribed for Grade 3-5 treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs)Citation44 occurring in at least 5% of patients in any arm of the KEYNOTE-048 trial or other trials for alternative comparatorsCitation12–15,Citation19,Citation40. The observed proportion of patients experiencing TRAEs was converted into weekly probabilities based on time-on-treatment (ToT) from KEYNOTE-048 (for pembrolizumab monotherapy, pembrolizumab combination therapy, and the EXTREME regimen) and estimated using PFS data (as a proxy for ToT) for other comparators. Due to the availability of multiple RCTs for platinum+5-FU, a weighted average rate of TRAE was derived using the respective study population size of each trial (Supplemental Material, Table S1).

Table 1. Drug regimens and the calculated average cost per week.

Costs

Direct medical costs (in 2020 US dollars) from the perspective of US third-party payers included treatment-related costs (drug acquisition, one-time PD-L1 testing for pembrolizumab monotherapy, drug administration, TRAE management, and subsequent treatments) and disease management costs (health state weekly costs, one-time disease progression costs, and terminal care).

Drug acquisition costs were calculated based on public prices ()Citation45. Except for pembrolizumab, for which the dosing was 200 mg fixed dose intravenously every 3 weeks for a maximum of 35 cycles (2 years)Citation31, average drug costs for other therapies were approximated using the least expensive combination of vials for an average patient without allowing for vial sharing between patients. The drug cost for cetuximab was based on a weekly schedule until disease progression, without a maximum number of treatment cyclesCitation46, whereas for cisplatin, carboplatin, docetaxel, paclitaxel, and 5-FUCitation46–51, drugs were administered once every three weeks for a maximum of six cycles. For platinum-based therapies with either carboplatin or cisplatin, the average cost was calculated assuming that 42.13 and 57.87% of patients receive cisplatin and carboplatin, respectively, based on the KEYNOTE-048 trial. Each cycle, the cost for drug acquisition and their administration were applied to patients still on treatment based on ToT curves. For pembrolizumab monotherapy, pembrolizumab combination therapy, and the EXTREME regimen, ToT was derived using KEYNOTE-048 trial data and for other model comparators, extrapolated PFS curves were used as a proxy for ToT data ().

PD-L1 testing costs shown in were applied only for pembrolizumab monotherapy, indicated in R/M HNSCC patients with CPS ≥1. The cost was derived by considering the totality of all tests performed in R/M HNSCC patients, including the tests performed on R/M HNSCC patients with CPS <1. As each test cost is $127.40Citation52, and 85.2%Citation32 of patients have a CPS ≥1, a one-time cost for PD-L1 testing of $149.53 per patient was applied for the pembrolizumab monotherapy group.

Table 2. Model inputs for direct medical costs and health utility.

Drug administration costs shown in for time and resources spent on intravenous infusions were based on the national payment amount from the 2020 Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) payment rates (4th Edition)Citation52. The administration costs for paclitaxel were calculated based on 24 h of infusion for each dose. As the infusion of 5-FU is assumed to take place at home (the device is installed on day 1 and removed on day 4), the cost for 1 h of infusion for a subsequent agent was added to 5-FU-containing regimens. For the cetuximab loading dose, 2 h of infusions were applied. For all the other treatment administrations, the cost for 1 h of infusion time was applied, including pembrolizumab for which the infusion lasts 30 min.

The weekly cost of TRAE management shown in was applied to the number of patients still on treatment and was obtained by multiplying the number of TRAE occurring each week by their respective management costs (derived based on diagnosis-related group [DRG])Citation53 (Supplemental Material, Tables S1 and S2).

In each cycle, the disease management cost for each health state shown in was applied to the number of patients in the corresponding states. These were estimated as a weekly average cost for providing routine follow-up care and patient monitoring including CT scans, blood tests, and consultations with healthcare practitioners to evaluate disease activity (Supplemental Material, Table S3). The weekly costs were obtained by multiplying the current procedural terminology (CPT) code-based unit costCitation52 for each type of visit or procedure by their weekly utilization in each respective health state, which was sourced from the literatureCitation54. When necessary, the unit costs were calculated as a weighted average across several CPT codes. In addition, at disease progression, a one-time cost was included by assuming an oncologist visit and a CT scanCitation55. The one-off progression cost was applied to the difference in the progressive disease health state occupancy in each model cycle plus progression-related deaths occurring during each cycle. The proportion of progression-related deaths was calculated by taking the ratio between progressive disease health state occupancy and the total number of patients alive at cycle entry.

Table 3. Base-case cost-effectiveness analysis results for first-line pembrolizumab vs. comparators in R/M HNSCC over a 20-year time horizon.

The costs for terminal care representing care given in the weeks or months before death is shown in were modeled separately and applied as a one-time cost at deathCitation56.

Using KEYNOTE-048 trial data, a one-time cost of subsequent treatment after the initial therapy with pembrolizumab or a comparator was assessed () and applied at the time of treatment discontinuation. For the non-trial comparators, the subsequent treatment costs were assumed the same as for the EXTREME regimen. The average cost of subsequent treatment was determined based on the expected proportions of patients receiving each subsequent therapy, and on their associated average cost (estimated based on public prices), recommended dosing schedule, mean ToT, drug administration costs, and TRAE costs (Supplemental Material, Tables S4 and S5). Based on KEYNOTE-048 trial, in patients with CPS ≥1, 75.74 and 92.41% received subsequent therapies following pembrolizumab monotherapy and EXTREME regimen, respectively, whereas in the overall population, the proportions treated after first-line pembrolizumab combination therapy and EXTREME regimen were 74.34 and 90.59%, respectively. The most utilized subsequent treatments within the KEYNOTE-048 trial were considered to derive subsequent treatment costs. Patients who received first-line pembrolizumab received costly regimens, such as cetuximab-containing regimens (45.09% in patients with CPS ≥1 and 39.36% in the overall R/M HNSCC population) in the second line, and none received a PD-1 inhibitor. However, among the patients with CPS ≥1 and in the overall R/M HNSCC population, 65.03 and 63.75% of those who received the EXTREME regimen as first-line treatment received a PD-1 inhibitor as subsequent treatment, and 8.67 and 8.50% received a cetuximab-containing regimen, respectively (Supplemental Material, Table S5). The duration of subsequent treatments was assumed independent of the primary treatment used and estimated by the mean durations derived from the KEYNOTE-048 clinical data across each intervention arm. The costs of treatment administration and of managing TRAEs for subsequent treatments were also includedCitation15,Citation16,Citation19,Citation41,Citation43,Citation57–59 (Supplemental Material, Table S5).

In each cycle, the one-off subsequent treatment cost is applied to newly discontinued patients, calculated as the difference in the ToT curve from each cycle to the next, and to a proportion of patients who die and are assumed to have received subsequent treatment before death. The proportion of patients incurring subsequent treatment costs before death was equal to the ratio between the number of patients off treatment and the number of patients alive during that cycle.

Health utility

Life-years were adjusted for quality of life using patient-level EuroQol five-dimension three-level (EQ-5D-3L) responses collected every three weeks before treatment discontinuation in the KEYNOTE-048 trial and mapped to an index score using the US social tariffCitation60. Health state utility values and disutility due to the presence of TRAEs and proximity to death in the last months of life were modeled using a multivariate linear mixed regression with the same weights applied to each treatment arm (Supplemental Material, Table S6). Based on the statistical significance of the covariates and clinical interpretations, the final model retained the ECOG score status (1 or >1) as an additional variable amongst several others also considered for inclusion, such as age, gender, smoking status, disease presentation (R/M or neither recurrent nor metastatic), human papillomavirus (positive or negative), baseline PD-L1 expression level, and tumor location (oral cavity or not). In each cycle, the health state utility weights were applied based on health state occupancy, the disutility associated with TRAE was applied to patients still on treatment, and the disutility associated with proximity to death was applied to new death events.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses were performed which are described in Supplemental Material (Table S7). A one-way deterministic sensitivity analysis (DSA) was described to assess the magnitude of the variations in the incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) induced by changes made in one parameter value. The results are summarized via a tornado diagram which ranks the 15 most influential parameters on the incremental cost per QALY gained with pembrolizumab vs. the EXTREME regimen. Uncertainty was further assessed through probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA), using 1000 iterations, in which standard errors or variance–covariance matrices for the selected parameter distributions were based on original data sources, when available, and otherwise were set at 20% of the mean values. In the current analysis, $100,000 per QALY was assumed as the threshold for cost-effectiveness, in alignment with the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review which uses the range of $100,000 to $150,000 per QALY as the standard value for health benefits for all economic assessments for the USCitation61. The results of the PSA are plotted graphically on cost-effectiveness acceptability curves showing the probabilities of cost-effectiveness at different willingness to pay thresholds going from $50,000 to $250,000 per QALY.

Results

Base-case analysis

Survival with pembrolizumab monotherapy was higher compared to any of the comparators. In year 2, for example, 29.6% of patients with CPS ≥1 on pembrolizumab monotherapy were alive vs. 17.2, 13.0, 13.2, and 22.4% of patients on the EXTREME regimen, platinum+5-FU, cisplatin + paclitaxel, and the TPEx regimen, respectively (). Pembrolizumab monotherapy dominated the EXTREME regimen among patients with CPS ≥1, decreasing total costs ($8110) and increasing life-years (+1.103) and QALYs (+0.867). Pembrolizumab was also dominant when compared to the TPEx regimen and resulted in ICERs of $86,827 and $81,473 per QALY gained vs. platinum+5-FU and cisplatin + paclitaxel, respectively ().

Survival with pembrolizumab combination therapy in the overall population was also higher vs. each comparator. Two years after treatment initiation, 30.0% of patients on pembrolizumab combination therapy were alive vs. 17.5, 12.9, 13.4, and 22.5% of patients on the EXTREME regimen, platinum+5-FU, cisplatin + paclitaxel, and the TPEx regimen, respectively (). Pembrolizumab combination therapy was cost-effective with an ICER of $1769 per QALY gained vs. the EXTREME regimen. In comparison with the EXTREME regimen, pembrolizumab increased total costs by $1846, and total life-years and QALYs by 1.329 and 1.044, respectively. Pembrolizumab combination therapy was dominant vs. TPEx regimen and the ICER vs. platinum+5-FU and cisplatin + paclitaxel were $81,989 and $89,505 per QALY gained, respectively ().

Sensitivity analyses

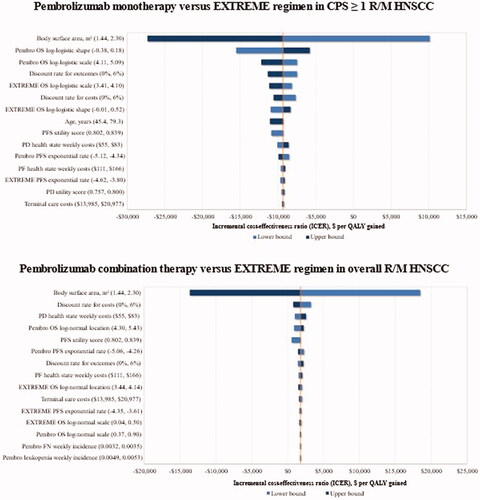

When key model parameters were varied in deterministic one-way sensitivity analyses according to defined lower and upper bounds (Supplemental Material, Table S7), the BSA and OS parameters were the key drivers of the ICER for pembrolizumab regimens in comparison with the EXTREME regimen (). The ICER for pembrolizumab monotherapy vs. EXTREME regimen ranged between −$27,340 and $10,126 per QALY gained, the negative ICERs indicating that pembrolizumab monotherapy dominated the EXTREME regimen. Despite varying the parametric assumptions for OS and PFS, pembrolizumab monotherapy was dominant vs. the EXTREME regimen in every scenario. Similarly, when comparing pembrolizumab combination therapy to the EXTREME regimen in the overall population, the ICER ranged between −$13,682 and $18,478 per QALY gained, with BSA revealed as being the key driver. These results were similar for the comparison of pembrolizumab regimens with other comparators although the BSA was the key driver for comparison with cetuximab-containing regimens.

Figure 2. The main variation in ICER of pembrolizumab regimens vs. the EXTREME regimen trial comparator upon one-way deterministic changes in model parameters. Abbreviations. CPS, combined positive score; EXTREME regimen, Cetuximab + platinum+5-Fluorouacil; PD, progressive disease; PF, progression-free; PFS, progression-free survival; QALY, quality-adjusted life years; R/M HNSCC, recurrent or metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; 5-FU, 5-fluorouracil.

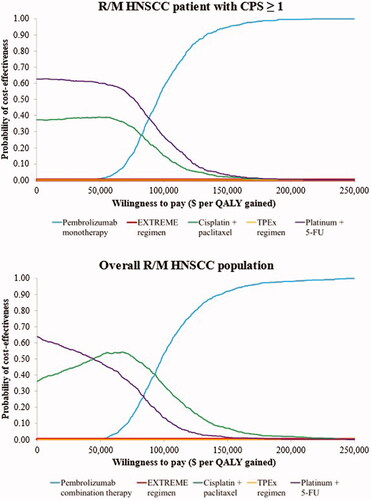

The results of the PSA are presented graphically using cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (). Considering the $100,000 per QALY threshold, pembrolizumab monotherapy in patients with CPS ≥1 and pembrolizumab combination therapy in the overall population are the regimens with the highest probability of cost-effectiveness.

Figure 3. Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves for pembrolizumab monotherapy and comparators in R/M HNSCC patients with CPS ≥1 and pembrolizumab combination and comparators in the overall R/M HNSCC population. Abbreviations. CPS, combined positive score; EXTREME regimen, Cetuximab + platinum+5-Fluorouacil; QALY, quality-adjusted life years; R/M HNSCC, recurrent or metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; TPEx regimen, Cisplatin + docetaxel + cetuximab; 5-FU, 5-fluorouracil.

Discussion

The long-term prognosis of patients with R/M HNSCC is typically poor, highlighting the high unmet need for treatments that improve survival. Platinum-based and cetuximab-based chemotherapies (e.g. EXTREME regimen) have historically been standard treatments for these patientsCitation12–15. In KEYNOTE-048, pembrolizumab monotherapy in the CPS ≥1 population and pembrolizumab combination therapy in the overall R/M HNSCC population demonstrated increased OS in comparison with the EXTREME regimenCitation19. The safety profile was favorable with pembrolizumab monotherapy and similar with pembrolizumab combination therapy compared with the EXTREME regimen.

To support US payers making decisions about the reimbursement of oncology drugs and generate relevant cost evidence in defining oncology treatment pathwaysCitation25, we assessed the cost-effectiveness of pembrolizumab treatments compared with the KEYNOTE-048 trial comparator, and with other comparators relevant to the US landscape. We found pembrolizumab regimens were cost-effective from a third-party payer perspective. Pembrolizumab treatments conferred considerable survival gains and improved QALYs vs. each comparator and were cost-saving vs. the EXTREME and the TPEx regimens when used in monotherapy. In the overall population, pembrolizumab combination therapy cost slightly more than the EXTREME regimen but was cost-saving vs. the TPEx regimen. Both pembrolizumab regimens were cost-effective in the US vs. platinum+5-FU and cisplatin + paclitaxel at a commonly used threshold of $100,000 or $150,000 per QALYCitation61.

The primary driver of first-line therapy costs with pembrolizumab was ToT. In the KEYNOTE-048 clinical study, pembrolizumab patients stayed on treatment longer than patients receiving comparator regimens, consistent with the efficacy benefits observed. The mean ToT for patients receiving pembrolizumab monotherapy over the model time horizon was 6.9 vs. 6.2 months for the EXTREME regimen. For pembrolizumab combination, the mean ToT was 7.6 vs. 6.4 months for the EXTREME regimen. The additional costs for pembrolizumab regimens due to longer ToT over some of the comparators were economically justified by the health benefits they confer, i.e. improved survival and quality of life. Furthermore, treatment with pembrolizumab resulted in cost-offsets associated with lower adverse event costs due to the favorable safety profile of pembrolizumab monotherapy and subsequent treatment costs following initial therapy with pembrolizumab vs. comparators. One of the reasons for lower subsequent treatment costs was that patients from the comparator arm often received a PD-1 inhibitor in the second line whereas patients in the pembrolizumab arms did not. This trend of high PD-1 inhibitor utilization as subsequent treatment was also observed in a recent US real-world study; among platinum-progressed R/M HNSCC patients, 71% of patients received subsequent treatment with pembrolizumab or nivolumabCitation62.

Our results corroborate a previous analysis of the cost-effectiveness of first-line pembrolizumab vs. the EXTREME regimen for R/M HNSCC in the USCitation26. Pembrolizumab monotherapy was dominant among PD-L1 expressers with CPS ≥1, and pembrolizumab combination therapy was cost-effective using a $100,000 per QALY threshold ($66,630/QALY). While still cost-effective, the higher ICER compared to ours is primarily because Lang et al. leveraged utilities from older publications (2015 and 2011) for more advanced patient populations, as opposed to the KEYNOTE-048 trial which reflects first-line R/M HNSCC patients under current medical practices. This assumption resulted in much lower utilities for both the progression-free and progressed-disease health states. From a Chinese perspective, Lang et al. reported the pembrolizumab regimens to be not cost-effective when a threshold of $27,538 per QALY was usedCitation26. This can be explained by the price of pembrolizumab relative to cetuximab in China. In Argentina, first-line pembrolizumab regimens in R/M HNSCC were shown to be cost-effective vs. the EXTREME regimen from the public health care security systemCitation28. The results of the current study further establish the cost-effectiveness of pembrolizumab regimens in the US through comparison against the EXTREME regimen using trial-based data, and over other less costly treatment alternatives commonly utilized (i.e. platinum in combination with a taxane and with 5-FU), which was not explored in prior models.

This economic assessment has several strengths beginning with PFS and OS projections performed using KEYNOTE-048 clinical trial dataCitation32 and the inclusion of alternative comparators using an NMACitation29,Citation62. While long-term extrapolation of OS and PFS is subject to uncertainty, our projections were validated against available long-term survival data published in the evidence submitted to NICE for the EXTREME regimen in first-line R/M HNSCCCitation33 and also against more recently available long-term KEYNOTE-048 trial data with about 4.5 years of follow up, which showed a small deviation between extrapolated curves and trial dataCitation63. Furthermore, the cost-effectiveness model results were confirmed over a broad range of deterministic and PSA varying assumptions including the extrapolation of OS and PFS, disease management cost, and health utilities. In addition, utility and disutility values used were obtained from KEYNOTE-048 study data and therefore, are considered representative of the target population for pembrolizumab.

In this model only grade 3–5 TRAEs with >5% incidence were included. The use of this threshold may have underestimated their impact given pembrolizumab monotherapy has a more favorable tolerability profile than the chemotherapy-containing comparator regimens. It should be noted though that the contribution of TRAEs to costs was low in the model. Another limitation of this model might be that in the pembrolizumab interventions and EXTREME regimen arms of the KEYNOTE-048 study, PFS was shorter than ToT. This was driven by a few patients receiving treatment beyond disease progression. However, in clinical practice, therapies are commonly administered on a treat-to-progression basis and therefore, the costs of pembrolizumab and comparator treatments might have been overestimated.

Conclusions

First-line pembrolizumab monotherapy for patients with CPS ≥1, and pembrolizumab combination therapy in the overall R/M HNSCC population show substantial clinical benefits in terms of OS and QALYs gained and are cost-effective treatment options compared with alternative regimens at a $100,000 per QALY threshold in the US. Our study provides an informative economic assessment that can support healthcare payers making decisions regarding the reimbursement of therapies for R/M HNSCC.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was supported by Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

RHB, KR, and DC are employees of Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA. JG and PD are employee of Complete Health Economics Outcomes Research Solutions, which received consultancy fees from Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (54.9 KB)Acknowledgements

None reported.

References

- National Cancer Institute. Head and neck cancers [cited 2020 Oct 30]. Available from: https://www.cancer.gov/types/head-and-neck/head-neck-fact-sheet

- Union for International Cancer Control. Locally advanced squamous carcinoma of the head and neck; 2014 [cited 2020 Nov 24]. Available from: https://www.who.int/selection_medicines/committees/expert/20/applications/HeadNeck.pdf

- International Agency for Research on Cancer-World Health Organization. Estimated number of new cases in 2020 [cited 2021 May 7]. Available from: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/home

- American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures; 2021 [cited 2021 Jun 18]. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2021/cancer-facts-and-figures-2021.pdf

- National Cancer Institute-Surveillance Research Program. SEER*Stat software version 8.2.1: incidence (relative survival) – total U.S., 1969–2012 counties. Data on file; 2013.

- Pfister DG, Spencer S, Adelstein D, et al. Head and neck cancers, version 2.2020. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2020;18(7):873–898.

- Winquist E, Agbassi C, Meyers BM, et al. Systemic therapy in the curative treatment of head and neck squamous cell cancer: a systematic review. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;46(1):29.

- Ang KK, Chen A, Curran WJ, et al. Head and neck carcinoma in the United States: first comprehensive report of the longitudinal oncology registry of head and neck carcinoma (LORHAN). Cancer. 2012;118(23):5783–5792.

- Cooper JS, Zhang Q, Pajak TF, et al. Long-term follow-up of the RTOG 9501/intergroup phase III trial: postoperative concurrent radiation therapy and chemotherapy in high-risk squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;84(5):1198–1205.

- Bernier J, Domenge C, Ozsahin M, et al. Postoperative irradiation with or without concomitant chemotherapy for locally advanced head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(19):1945–1952.

- Pignon JP, Maître A l, Maillard E, et al. Meta-analysis of chemotherapy in head and neck cancer (MACH-NC): an update on 93 randomised trials and 17,346 patients. Radiother Oncol. 2009;92(1):4–14.

- Forastiere AA, Metch B, Schuller DE, et al. Randomized comparison of cisplatin plus fluorouracil and carboplatin plus fluorouracil versus methotrexate in advanced squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck: a southwest oncology group study. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10(8):1245–1251.

- Jacobs C, Lyman G, Velez-García E, et al. A phase III randomized study comparing cisplatin and fluorouracil as single agents and in combination for advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10(2):257–263.

- Gibson MK, Li Y, Murphy B, et al. Randomized phase III evaluation of cisplatin plus fluorouracil versus cisplatin plus paclitaxel in advanced head and neck cancer (E1395): an intergroup trial of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(15):3562–3567.

- Vermorken JB, Mesia R, Rivera F, et al. Platinum-based chemotherapy plus cetuximab in head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(11):1116–1127.

- Ferris RL, Blumenschein G, Fayette J, et al. Nivolumab for recurrent squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(19):1856–1867.

- Bauml J, Seiwert TY, Pfister DG, et al. Pembrolizumab for platinum- and cetuximab-refractory head and neck cancer: results from a single-arm, phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(14):1542–1549.

- Colevas AD, Bahleda R, Braiteh F, et al. Safety and clinical activity of atezolizumab in head and neck cancer: results from a phase I trial. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(11):2247–2253.

- Burtness B, Harrington KJ, Greil R, et al. Pembrolizumab alone or with chemotherapy versus cetuximab with chemotherapy for recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (KEYNOTE-048): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2019;394(10212):1915–1928.

- Siu LL, Even C, Mesía R, et al. Safety and efficacy of durvalumab with or without tremelimumab in patients with PD-L1-Low/negative recurrent or metastatic HNSCC: the phase 2 CONDOR randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(2):195–203.

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration. FDA approves pembrolizumab for first-line treatment of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. FDA; 2019 [cited 2021 Jan 19]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-pembrolizumab-first-line-treatment-head-and-neck-squamous-cell-carcinoma

- De Felice F, de Vincentiis M, Valentini V, et al. Follow-up program in head and neck cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2017;113:151–155.

- Machiels J-P, René Leemans C, Golusinski W, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity, larynx, oropharynx and hypopharynx: EHNS-ESMO-ESTRO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Oral Oncol. 2021;113(11):105042.

- BlueCross BlueShield of North Carolina. Medical oncology program and cancer treatment pathways [cited 2022 Jun 22]. Available from: www.medicaloncologyprogram.com

- AIM Specialty Health. AIM cancer treatment pathways – anthem cancer care quality program [cited 2022 Jun 22]. Available from: https://aimproviders.com/medoncology-anthem/about-the-program/cancer-treatment-pathways/

- Lang Y, Dong D, Wu B. Pembrolizumab vs the EXTREME regimen in recurrent or metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Clin Drug Investig. 2020;40(12):1137–1146.

- Zhou K, Li Y, Liao W, et al. Pembrolizumab alone or with chemotherapy for squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: a cost-effectiveness analysis from Chinese perspective. Oral Oncol. 2020;107:104754.

- Wurcel V, Chirovsky D, Borse R, et al. Cost-effectiveness of pembrolizumab regimens for the first-line treatment of recurrent or metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in Argentina. Adv Ther. 2021;38(5):2613–2630.

- Keeping (Precision XTRACT) S. Network meta-analysis of pembrolizumab for the first-line treatment of recurrent/metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (R/M HNSCC); 2019. Data on file.

- Ramakrishnan K, Mojebi A, Ayers D, et al. Network meta-analysis (NMA) of pembrolizumab for first-line (1L) treatment of recurrent/metastatic (R/M) head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC). J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(15_suppl):e18012.

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration-Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Highlights of prescribing information – KEYTRUDA® (Pembrolizumab); 2021 [cited 2021 Jun 10]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/125514s096lbl.pdf

- Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. KEYNOTE-048 clinical study report. Data file; 2019.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Cetuximab for treating recurrent or metastatic squamous cell cancer of the head and neck; 2017 [cited 2020 Oct 30]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta473

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Nivolumab for treating recurrent or metastatic squamous-cell carcinoma of the [ID971], head and neck after platinum-based chemotherapy; 2017 [cited 2020 Oct 30]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta490/documents/committee-papers

- Bagust A, Greenhalgh J, Boland A, et al. Cetuximab for recurrent and/or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: a NICE single technology appraisal. Pharmacoeconomics. 2010;28(6):439–448.

- Woods B, Sideris E, Palmer S, et al. NICE DSU technical support document 19: partitioned survival analysis for decision modelling in health care: a critical review report by the decision support unit; 2017 [cited 2021 Apr 30]. Available from: www.nicedsu.org.uk

- Elbasha EH, Chhatwal J. Theoretical foundations and practical applications of within-cycle correction methods. Med Decis Making. 2016;36(1):115–131.

- Latimer N. NICE DSU technical support document 14: survival analysis for economic evaluations alongside clinical trials-extrapolation with patient-level data report by the decision support unit; 2011 [cited 2020 Aug 28]. Available from: www.nicedsu.org.uk

- Chow GC. Tests of equality between sets of coefficients in two linear regressions. Econometrica. 1960;28(3):591.

- Guigay J, Aupérin A, Fayette J, et al. Cetuximab, docetaxel, and cisplatin versus platinum, fluorouracil, and cetuximab as first-line treatment in patients with recurrent or metastatic head and neck squamous-cell carcinoma (GORTEC 2014-01 TPExtreme): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(4):463–475.

- Bossi P, Miceli R, Locati LD, et al. A randomized, phase 2 study of cetuximab plus cisplatin with or without paclitaxel for the first-line treatment of patients with recurrent and/or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(11):2820–2826.

- Friesland S, Tsakonas G, Kristensen C, et al. Randomised phase II study with cetuximab in combination with 5-FU and cisplatin or carboplatin versus cetuximab in combination with paclitaxel and carboplatin for treatment of patients with relapsed or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (CETMET trial). J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(15_suppl):6032–6032.

- Burtness B, Goldwasser MA, Flood W, et al. Phase III randomized trial of cisplatin plus placebo compared with cisplatin plus cetuximab in metastatic/recurrent head and neck cancer: an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(34):8646–8654.

- U.S. Departement of Health and Human Services. Common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE) Version 4.0; 2009 [cited 2020 Oct 30]. Available from: https://evs.nci.nih.gov/ftp1/CTCAE/CTCAE_4.03/Archive/CTCAE_4.0_2009-05-29_QuickReference_8.5x11.pdf

- Medi-Span Price Rx; 2020 [cited 2021 Jan 20]. Available from: https://go.wolterskluwer.com/medispan-price-rx-bcom.html

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration-Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Highlights of prescribing information – ERBITUX® (cetuximab); 2019 [cited 2021 Jun 23]. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/medicaldevices/productsandmedicalprocedures/invitrodiagnostics/ucm301431.htm

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration-Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Highlights of prescribing information – Cisplatin; 2019 [cited 2021 Jun 23]. Available from: www.fda.gov/medwatch

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration-Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Highlights of prescribing information – PARAPLATIN® (Carboplatin) [cited 2021 May 20]. Available from: www.fda.gov/medwatch

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration-Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Highlights of prescribing information – TAXOTERE (Docetaxel); 2020 [cited 2021 Jun 23]. Available from: www.fda.gov/medwatch

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration-Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Highlights of prescribing information – ABAXANE (paclitaxel); 2020 [cited 2021 Jun 23]. Available from: www.fda.gov/medwatch

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration-Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Highlights of prescribing information – Fluorouracil; 2016 [cited 2021 Jun 23]. Available from: www.fda.gov/medwatch

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Current procedural terminology. 4th ed.; 2020. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/apps/physician-fee-schedule/search/search-criteria.aspx

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). ICD-10-CM/PCS MS-DRG v37.0 definitions manual. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/icd10m/version37-fullcode-cms/fullcode_cms/P0002.html

- Nash Smyth E, La E, Talbird S, et al. Treatment patterns and health care resource use (HCRU) associated with repeatedly treated metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (mSCCHN) in the United Kingdom (UK); 2015.

- American Academy of Professional Coders (AAPC). Current procedural terminology – codify by AAPC. Available from: https://www.aapc.com/codes/cpt-codes-range?rf=aapc

- Enomoto LM, Schaefer EW, Goldenberg D, et al. The cost of hospice services in terminally ill patients with head and neck cancer. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;141:1066–1074.

- Guigay J, Fayette J, Mesia R, et al. TPExtreme randomized trial: TPEx versus extreme regimen in 1st line recurrent/metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (R/M HNSCC). J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(15_suppl):6002–6002.

- Cohen EEW, Soulières D, Le Tourneau C, et al. Pembrolizumab versus methotrexate, docetaxel, or cetuximab for recurrent or metastatic head-and-neck squamous cell carcinoma (KEYNOTE-040): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2019;393(10167):156–167.

- Fayette J, Wirth L, Oprean C, et al. Randomized phase II study of duligotuzumab (MEHD7945A) vs. cetuximab in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (MEHGAN study). Front Oncol. 2016;6:232.

- Shaw JW, Johnson JA, Coons SJ. US valuation of the EQ-5D health states: development and testing of the D1 valuation model. Med Care. 2005;43(3):203–220.

- Institute for Clinical and Economic Review. 2020–2023 Value assessment framework; 2020. Available from: https://icer.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/ICER_2020_2023_VAF_102220.pdf

- Ramakrishnan K, Liu Z, Baxi S, et al. Real-world time on treatment with immuno-oncology therapy in recurrent/metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Future Oncol. 2021;17(23):3037–3050.

- Borse R, Hu P, Ramakrishnan K, et al. Validity of long-term oncology modeling extrapolations: a case study in recurrent or metastatic head and neck cancer. POSA132,2021-11; 2021.