Abstract

Aims

To analyze secondary objectives of the REGAIN study related to acute headache medication use and healthcare resource utilization (HCRU) in patients with chronic migraine treated with galcanezumab, a monoclonal antibody to calcitonin gene-related peptide.

Methods

Adults with chronic migraine (N = 1,113) were randomized (2:1:1) and treated with double-blind monthly injections of placebo, galcanezumab-120 mg, or galcanenzumab-240 mg for 3 months, followed by a 9-month open-label extension with 120 or 240 mg/month galcanezumab. Headache and medication information was collected by daily eDiary. HCRU was reported for the 6 months before randomization, monthly thereafter, and converted to rate per 100-patient-years.

Results

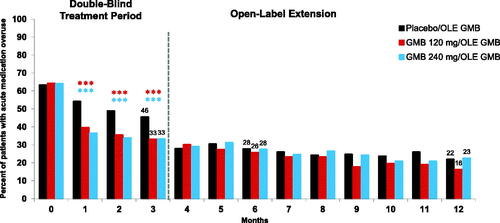

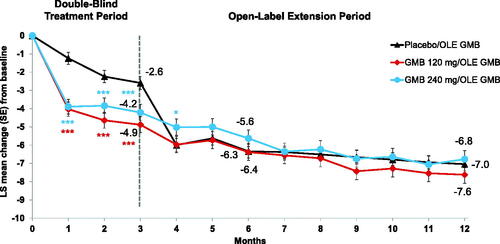

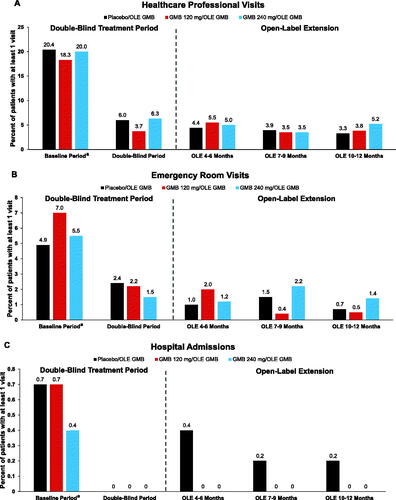

At baseline, 63–64% of patients met criteria for acute headache medication overuse. At Month 3, incidence of headache medication overuse in the galcanezumab groups (33% and 33%) was significantly lower than in the placebo group (46%, both p < .001) and was 16% and 23% in the previous-galcanezumab groups at Month 12. From a baseline of 14.5 to 15.5, reduction in mean number of monthly migraine headache days with acute headache medication use was also significantly greater in the galcanezumab groups at Month 3 (−4.2 and −4.9) than in placebo (−2.6, both p < .001), with reductions of −6.8 and −7.6 in the previous-galcanezumab groups at Month 12. Migraine-specific HCRU rates decreased for all groups, with no significant between-group differences at Month 3. At Month 12, in the two previous-galcanezumab groups, emergency room visits decreased by 58% and 75%, hospital admissions by 100%, and healthcare professional visits by 54% and 67%.

Limitations

Only 3 months of double-blind, placebo-controlled data, a longer HCRU recall period for baseline than postbaseline, and patients receiving care in the clinical trial itself, may limit generalizability.

Conclusions

Treatment with galcanezumab resulted in significant reductions in headache medication overuse and migraine headache days requiring acute medication use, with notable reductions in migraine-specific HCRU.

Clincal trial registry::

Introduction

Among people with chronic migraine, the prevalence of acute medication overuse may be as high as 60–65%Citation1, and rates of migraine-specific emergency room visits range from approximately 12% to 30% across the globeCitation2,Citation3. Chronic migraine is diagnosed based on specific headache frequency criteria (≥15 headache days/month for >3 months with features of migraine on ≥8 days/month), while episodic migraine represents the other side of the spectrum (<15 headaches days/month)Citation4,Citation5. Chronic migraine may present immediatelyCitation6 or evolve from episodic migraine to chronic migraine over months or yearsCitation7,Citation8 and is linked to the following risk factors: high frequency of attacks (episodic migraine), overuse of acute migraine medications, ineffective acute therapy, obesity, anxiety and depression, and stressful life eventsCitation8–11. Accordingly, disease burden is substantially higher in people with chronic migraine than those with episodic migraine, including greater rates of headache-related disability, poorer quality of life, and higher rates of comorbid medical and psychiatric conditions and healthcare resource utilization (HCRU)Citation12.

The high economic burden associated with migraine is driven by both direct and indirect costsCitation2,Citation13–16 and is considered the costliest of the purely neurological diseasesCitation17. The majority of direct costs are for outpatient services as opposed to hospital stays such as medications, office or clinic visits, urgent care visits, outpatient infusion visits to mitigate migraine attacks, emergency room visits, laboratory and diagnostic services, and management of treatment-associated side effects. Indirect costs from lost productivity in the workplace are also substantialCitation18. Following the initiation of preventive therapy in 264 patients, although 6-month triptan costs increased by $5,423 (19%), substantial reductions in headache-related visits to the office and emergency room were observed (32% and 49%, respectively) and were associated with a net savings of $18,757, despite the increase in costs for triptansCitation18. In addition, among some patients with chronic migraine, acute treatments become less effective over time, and utilization increases to the point of meeting the criteria for medication overuse headache, which is associated with even greater disability and economic burdenCitation19,Citation20.

Although numerous oral preventive medications (prior to the availability of calcitonin gene-related peptide [CGRP] antibodies) have the potential to reduce migraine attack frequency and severity especially for episodic migraineCitation21, few drugs have been proven effective for the treatment of chronic migraine in robust clinical studiesCitation10,Citation22, and many are discontinued early due to lack of efficacy, poor tolerability, or bothCitation23,Citation24. Ford et al.Citation25 recently reported that in patients with episodic or chronic migraine, >75% switched or discontinued their initial preventive treatment within 12 months of initiation for medications available in 2011. Regardless, all people with chronic migraine require preventive medicationCitation10. Notably, adherence to effective preventive medications is often associated with reductions in acute medication use for migraine and reversion from chronic migraine to episodic migraineCitation8. However, the Phase 3 REsearch Evaluating Migraine Prophylaxis Therapy 1 (PREEMPT 1) study failed to demonstrate a significant reduction in overall acute headache pain medication use following onabotulinumtoxinA vs placebo as a preventive medication in adults with chronic migraineCitation26.

Galcanezumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody that binds CGRP and is approved for the preventive treatment of migraine in adults based on Phase 3 studies in both episodic and chronic migraineCitation27–29. Reductions in acute medication use and HCRU have already been reported for a 12-month open-label study of galcanezumab, among patients with primarily episodic migraineCitation30. Therefore, it is important to evaluate changes in acute medication use and HCRU in patients with chronic migraine following preventive treatment with galcanezumab (120 mg and 240 mg). This research is based on the 1-year findings from a randomized, 3-month double-blind, placebo-controlled Phase 3 study (REGAIN) with a 9-month open-label extension (OLE) period of galcanezumab. The prespecified analysis hypothesis is that galcanezumab significantly reduces the number of migraine headache days with acute medication use and decreases HCRU in patients with chronic migraine.

Methods

Study design

Details of the study’s design have been published previouslyCitation29. Briefly, the study REGAIN consisted of an initial screening and washout (3–45 days); a prospective lead-in or baseline period wherein the frequency of migraine headache days or probable migraine headache days was determined (30–40 days); 3-month double-blind treatment period (Months 1–3), a 9-month optional OLE period (Months 4–12) and a 4-month post-treatment (washout) period (Months 13–16). During the double-blind treatment period, patients were randomized to receive 2:1:1 monthly subcutaneous injection of placebo:galcanezumab 120-mg (with a galcanezumab 240-mg loading dose): galcanezumab 240 mg/month. Randomization was stratified within country by presence or absence of acute headache medication overuse during the 30-day baseline, and presence or absence of concurrent migraine prophylaxis. At the first OLE injection visit (end of Month 3), all patients including those who received placebo during the double-blind treatment period received a loading dose of galcanezumab 240 mg. At Month 4, all patients received a maintenance dose of galcanezumab 120 mg. At Month 5 and onwards, patients received either galcanezumab 120 mg or galcanezumab 240 mg based on the investigator’s discretion. At baseline and during treatment and post-treatment periods, headache information, such as pain severity and duration, other related symptoms, and acute medication use, were recorded using a hand-held electronic diary (eDiary) device. Patients were also permitted to take specified acute migraine medications during these periods.

This study is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02614261). The study protocol was reviewed and approved by appropriate institutional review boards at each study site and was conducted according to Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki. Patients provided written informed consent before initiating study procedures.

Patient selection

Key inclusion criteria: Both male and female, 18–65 years of age, diagnosis of chronic migraine per the International Classification of Headache Disorders 3rd edition (ICHD-3, beta version)Citation5 criteria, i.e. ≥15 headache days/month for >3 months, of which at least eight were monthly migraine headache days, migraine onset prior to 50 years of age, a history of at least one headache-free day/month for 3 months prior to study entry as well as at least one headache-free day during the prospective baseline period. Preventive migraine medications were not allowed, except for stable doses of topiramate or propranolol which were allowed in a small subset (15%) of patientsCitation29. Patients with a history of headache other than migraine, tension type headache, or medication overuse headache within 3 months prior to randomization were excluded.

Outcome measures

Acute medication use for headache was captured in the daily eDiary. The number of migraine headache days per month with acute headache medication use was a prespecified secondary outcome measure based on patients’ eDiary entries. Allowable headache treatments included acetaminophen (paracetamol); nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs); triptans; ergotamine and derivatives; isometheptene mucate, dichloralphenazone, and acetaminophen combination (Midrin); or combinations thereof. The following medications were allowed with restrictions: (1) opioid and barbiturates no more than 3 days/month and (2) single dose of injectable steroids allowed only once during the study, in an emergency setting. The name and dose of concomitant medications used for the acute treatment of migraine or headache and the use of other pain medications were captured.

Change in HCRU (including migraine-specific HCRU) was a prespecified secondary objective of the study. At baseline, patients reported HCRU for the previous 6 months and then monthly during the treatment periods. Specifically, the HCRU was solicited by study personnel while documenting patient responses and included three questions related to (1) emergency room visits, (2) hospital inpatient admissions, and (3) any other visits with a healthcare professional that occurred since the patient’s last study visit that were not associated with their participation in the study. When patients reported an event, they were also asked about frequency or length of stay and the number of healthcare events that were related to migraine.

Acute medication overuse definition

Acute medication overuse was determined during the prospective baseline period based on patients’ eDiary entries. Acute medication overuse criteria were adapted from Section 8.2 of the ICHD-3 (beta version) guidelinesCitation5 and were prespecified in the statistical analysis plan. At baseline, medication overuse was defined as present if a patient exceeded the thresholds for total number of days of use for any of the following drug classes (or medications containing drugs from these classes) during the 30-day prospective baseline period as reported in the electronic diary: triptans for ≥10 days, ergot or ergotamine derivative for ≥10 days, NSAIDs or aspirin for ≥15 days, acetaminophen/paracetamol for ≥15 days, any combination drugs containing ≥2 of the above medication classes for ≥10 days, and total days with drug use from ≥2 of the above categories ≥10 days. Analysis of medication overuse over time (at each postbaseline month) was conducted post hoc using the prespecified baseline definition of medication overuse.

Data analysis

The statistical models used in these analyses were prespecified in the original study protocols/statistical analysis plan or are consistent with those prespecified.

Results are presented by groups, per dose assignment during the double-blind treatment period: placebo, 120 mg galcanezumab (120 mg), and 240 mg galcanezumab (240 mg). Mean reductions across time in the number of migraine headache days/month with acute medication use were calculated for the following time periods: baseline through completion of double-blind treatment period (Month 3), baseline through Month 6 of the OLE, and baseline through Month 12 of the OLE. These mean values were estimated via restricted maximum likelihood-based mixed models with repeated measures with effects for treatment, pooled country, baseline medication overuse, concurrent prophylaxis use, month, treatment-by-month interaction, baseline, and baseline-by-month interaction. The incidences of acute medication overuse over time are reported using raw rates but were analyzed using a generalized linear mixed model for repeated measure binary outcomes with factors for treatment, baseline medication overuse, concurrent migraine preventive use, month, and treatment-by-month interaction. These models of acute medication overuse were run separately for the double-blind and OLE treatment periods. Mean migraine-specific HCRU across baseline to double-blind to OLE treatment periods (per 100 patient-years) was estimated with changes from baseline in exposure-adjusted rates compared within treatment using a Wilcoxon signed-rank test and compared between treatment and placebo with a Kruskal-Wallis test.

Analyses (SAS software version 9.4, SAS Institute, Cary, NC) included all patients who were randomized and received at least 1 dose of study drug and who had both a baseline and at least 1 postbaseline value. In cases where there were missing eDiary data on certain days of the month, the overall number of migraine headache days with medication were estimated using the observed count reweighted by the number of days with observations, but if a patient had less than 50% compliance with their eDiary entries in a given month, the month was considered missing. A two-sided p-value ≤.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Patients

A total of 1,903 patients were screened, of whom 1,113 patients with chronic migraine were randomized and received at least 1 dose of study drug (4 additional patients were randomized but did not receive study drug) (placebo, n = 558; 120 mg galcanezumab, n = 278; 240 mg galcanezumab, n = 277). A total of 1,073 patients who entered the double-blind period had sufficient data for HCRU analyses (placebo, n = 533; 120 mg galcanezumab, n = 269; 240 mg galcanezumab, n = 271). Overall, 1,037 of 1,113 patients (93.2%) completed treatment during the double-blind treatment period (placebo, 91.0%; 120 mg, 94.6%; 240 mg, 96.0%). A total of 1,021 patients entered the OLE period.

The patient population was predominately female (85.0%) and white (79.1%), with a mean age of 41.0 years (). Duration of migraine illness was on average 20–22 years, and during the baseline period, patients had an average of 21.4 headache days/month and 19.4 migraine headache days/month. A total of 63.8% of patients met criteria for acute headache medication overuse. Overall, treatment groups were balanced with respect to baseline demographics and disease characteristics, with a few exceptions. Mean age in the galcanezumab 120 mg group was significantly lower than in the placebo group (39.7 vs 41.6 years; p < .05). Mean duration of migraine illness was significantly lower in the galcanezumab 240 mg group than in the placebo group (20.1 vs 21.9 years; p < .05). At baseline, the mean number of migraine headache days/month with acute medication use for each treatment group was 15.5 for placebo, 15.1 for 120 mg galcanezumab, and 14.5 for 240 mg galcanezumab (p < .05 vs placebo).

Table 1. Baseline demographics and disease burden.

Acute medication use

Mean reductions in the number of migraine headache days/month with acute headache medication use were significantly greater (p < .001) for both galcanezumab dose groups compared to placebo starting in the first month and at each subsequent month in the double-blind treatment period, with continued reductions during the OLE, when all patients were receiving galcanezumab (). From the double-blind baseline (Month 0), mean changes in monthly migraine headache days with acute medication use at Month 3, Month 6, and Month 12, respectively, for the placebo group were −2.59, −6.34, and −7.04; for the 120 mg galcanezumab group were −4.88, −6.38, and −7.62; and for the 240 mg galcanezumab group were −4.21, −5.63, and −6.77. Baseline medication overuse status (presence or absence at baseline) was included as a control factor in the analysis model for mean change in monthly migraine headache days with acute medication, but this factor was highly non-significant in the model (p = 0.909), indicating that the presence of medication overuse did not reduce the efficacy of galcanezumab.

Figure 1. Mean change from baseline in the number of migraine headache days with acute medication use. Abbreviations: GMB, galcanezumab; LS, least squares; OLE, open-label extension; SE, standard error. *p < .05 vs previous placebo. ***p < .001 vs placebo.

Acute medication overuse at baseline was found in 63.4% of placebo, 64.3% of 120 mg galcanezumab, and 64.1% of 240 mg galcanezumab recipients (). During the double-blind and open-label treatment periods, acute medication overuse incidence declined from Month 1 through Month 12 (). Statistically significant separation of galcanezumab treatments (both 120 mg and 240 mg) from placebo was observed at each month during the double-blind treatment period (all p < .001), with changes from baseline continuing to be observed during the open-label treatment period. At Month 12, the percentage of patients with medication overuse had decreased to 22.0% in the previous placebo, 16.3% in the previous 120 mg galcanezumab, and 22.6% in the 240 mg galcanezumab groups.

Healthcare resource utilization

Incidence of HCRU during the study was low, with no statistically significant differences between groups (, ). When compared with baseline, the percentages of patients with a least 1 migraine-specific HCRU event declined in all 3 treatment groups with respect to healthcare professional visits, emergency room visits, and hospital admissions (defined as overnight hospital stays) during the double-blind and OLE periods (). Migraine-specific HCRU rates (events per 100 patient-years) in each study period are summarized in . Rate of postbaseline emergency room visits was consistently lower across all treatment groups (percent reductions ranged from 21% to 40% in the double-blind period and 58% to 79% in the OLE). Rates of hospital admissions were lower than baseline rates (100% reduction in all groups in the double-blind period and 21–100% reduction in the OLE), with reductions in durations (in days) of hospital stays by 100% in the double-blind period and 39–100% in the OLE. Rates of HCP visits were also lower than baseline rates (60–75% reduction in the double-blind period and 54–74% reduction in the OLE).

Figure 3. Migraine-specific healthcare resource utilization as count of patients with at least 1 visit (%) during treatment period. (a) Healthcare Professional Visits; (b) Emergency Room Visits; (c) Hospital Admissions. Abbreviations: GMB, galcanezumab; OLE, open-label extension period. aThe reported baseline value is the collected baseline value (previous 6 months) divided by 2.

Table 2. Migraine-specific healthcare resource utilization rates per 100 patient-yearsa.

Discussion

The analyses described for patients with chronic migraine in this Phase 3 clinical study found significant reductions in the number of migraine headache days requiring acute medication use for all classes of drugs as early as Month 1 and, as reported previously, were statistically significantly greater for both doses of galcanezumab compared to placebo for the 3-month double-blind treatment period. By the end of the OLE period (1 year from start of double-blind treatment), the number of migraine headache days requiring acute medication use was significantly reduced by approximately 50% overall (∼6–7 fewer treatments/month). Moreover, among all patients, the proportion with acute medication overuse decreased from 64% at baseline to 21% at Month 12, with significantly lower rates for galcanezumab compared to placebo during the 3-month double-blind treatment period. Finally, galcanezumab use was associated with meaningful reductions (∼50%) in the number of emergency room visits, hospital admissions (and reduced length of stay), and healthcare professional visits over 1 year. During the double-blind treatment period (3 months), statistical separation from placebo in migraine-specific HCRU was not observed.

The findings from our study are clinically relevant to both patients and practitioners as people with chronic migraine have high unmet needs. Overuse of acute medication is common among people with chronic migraine, placing them at risk of developing medication overuse headache and even greater disability and HCRUCitation1,Citation20. While the overall economic burden of chronic migraine is high, access to effective and tolerable preventive treatments that patients adhere to has the potential to decrease acute medication overuse and enable possible reversion of chronic migraine to episodic migraineCitation8.

Previous reports with other drugs for the preventive treatment of chronic migraine, including agents that inhibit CGRPCitation26,Citation31–36, corroborate our findings with galcanezumab in reducing acute medication use and support their integration into daily clinical practiceCitation37. Yet, an important distinction of the galcanezumab episodic and chronic migraine Phase 3 studiesCitation27–29 was that acute medication use was not limited to the use of triptans but was inclusive of all acute medications given to treat headache pain. In the PREEMPT 1 study, a post hoc analysis in patients with chronic migraine found that triptan use was significantly reduced from baseline in the onabotulinumtoxinA vs placebo group (−3.3 vs −2.5, respectively; p = .023) at Week 24; however, overall acute medication use was not significantly decreased between onabotulinumtoxinA vs placeboCitation26. Another study, which included patients who overused acute pain medications during the 1-month baseline period, demonstrated that onabotulinumtoxinA 195 U significantly reduced acute pain medication intake days/month from baseline to 3 months, 12 months, and 24 months of therapy (pretreatment, 21.0 ± 5.1; 3 months, 13.8 ± 3.2; 12 months, 5.6 ± 1.4; and 24 months, 3.7 ± 1.3; all p < .001) Citation32. In a Phase 2 study, significant reductions from baseline in monthly acute migraine-specific drug treatment days were observed after administration of erenumab 70 mg (−3.5; p < .0001) and erenumab 140 mg (−4.1; p < .0001) vs placebo (−1.6) during the last 4 weeks of the 12-week double-blind treatment periodCitation34. A post hoc analysis in patients with chronic migraine on fremanezumab 675/225 mg and 900 mg also found that a greater percentage of patients achieved at least a 50% reduction in days of acute medication use across all three months of the double-blind study relative to placebo-treated patients (26% and 22% vs 11% placebo, p = .0098 and p = .0492)Citation35.

In 2010, there were 1.2 million (95% confidence interval, 0.9–1.4 million) migraine emergency room visits in the United States, although the estimate is likely higher because many people with migraine may be assigned a nonspecific headache diagnostic code upon presentation at the emergency roomCitation38,Citation39. Notably, the most common reason for people with migraine presenting to the emergency room in the past year was unbearable pain; thus, emergency room use may represent a marker for suboptimal ongoing disease managementCitation40. The International Burden of Migraine Study found that HCRU was high among people with migraine in 9 countries, and those with chronic migraine used more healthcare resources (primary care, neurologist, emergency room visits, and hospitalizations) than people with episodic migraineCitation41. Therefore, in addition to the previously reported favorable efficacy, safety, and tolerability profile of galcanezumabCitation29, the results of our acute medication use and HCRU analyses demonstrate statistically significant reductions in acute medication use as early as Month 1 as well as reductions in healthcare professional visits, emergency room visits, hospital admissions, and length of overnight hospitalization stays.

There are few published results evaluating changes in HCRU when patients are treated with a preventive medication for chronic migraine. Rothrock et al. reported that 6-month onabotulinumtoxinA treatment in patients with chronic migraine led to 55% fewer emergency room visits, 59% fewer urgent care visits (changes in healthcare professional visits were not reported), and 57% fewer hospitalizations, compared with the 6 months predating initial treatment in a real-world setting (p < .01 for all)Citation31. Unlike onabotulinumtoxinA, galcanezumab can be self-administered at home via an autoinjector with only 1 monthly injection, after the 2-injection loading dose at initiation. The HCRU results for the patients randomized and treated with galcanezumab (120 mg or 240 mg) in our study were generally consistent with those of Rothrock et al.Citation31.

The results presented herein must be interpreted based on several potential limitations. Restrictions in the inclusion criteria, such as the exclusion of patients who have failed more than 3 standard-of-care preventive medications due to lack of efficacy, may limit the generalizability of the data presented. However, a strength was that patients with medication overuse headache in the past 3 months were not excluded. Medication overuse headache is common among patients with chronic migraine but often goes undiagnosed; therefore, the study applied predefined medication overuse criteria based on ICHD-3 (beta version) definitionsCitation5 to identify this higher risk subpopulation. Another limitation is that although the 3-month duration of the double-blind treatment period is sufficient to demonstrate efficacy, it may not be long enough to demonstrate the ultimate effects of the treatment. Inclusion of the 9-month OLE analysis provides added confidence in longer-term findings albeit these data are uncontrolled. The study design also introduced dosing fluctuations in the OLE that may confound the results and are unlikely in clinical practice. Also, at baseline, patients had to recall HCRU for the past 6 months. However, a 6-month recall period is more likely to be associated with underreporting or accurate reporting (76%) vs overreporting HCRU (25%)Citation42. Specifically among patients with chronic illnesses and higher HCRU, a 6-month recall period of self-reported physician visits was found to be underreported, while emergency room visits and hospitalizations had low discrepancy, with only slight overestimation among patients with higher utilizationCitation43. The present study was a Phase 3 registration study that required monthly clinical site visits, and HCRU in real-world settings have not yet been evaluated for galcanezumab. Furthermore, this study was not powered to specifically address changes in HCRU, and incidence of HCRU was relatively low, with most patients reporting no such events at baseline, particularly with respect to emergency room visits and hospitalizations. Moreover, clinical trial participation itself may reduce the need for care. Exposure-adjusted changes in migraine-specific HCRU rates are reported to give a clearer representation of observed differences; however, a much larger clinical trial would be needed to determine if those differences were clinically relevant. There are also several strengths for this study, including the international population, longer-term follow-up, evaluation of acute medication overuse, use of a 1-month prospective baseline period, use of a daily headache diary to capture acute medication use, and the monthly evaluation of HCRU during the treatment periods.

Conclusions

The findings described herein indicate that in addition to significant and clinically meaningful reductions in migraine headache daysCitation29, galcanezumab also reduces acute medication use and medication overuse in patients with chronic migraine. Galcanezumab treatment was also associated with reductions in HCRU over 1 year. Clinicians are in need of preventive treatments that are effective, safe, and tolerable for this debilitating neurological disease. When ineffectively treated, this patient population is at great risk of developing medication overuse headache with substantial additional burden, including poor health-related quality of life, severe headache-related disability, and higher direct and indirect costsCitation17,Citation44,Citation45. Overall, this research indicates that galcanezumab is a suitable treatment option for clinicians to consider when treating patients with chronic migraine and has the potential to reduce utilization of healthcare services and acute headache medications.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

Eli Lilly and Company provided the funding for this study.

Declaration of financial/other interests

Dr. Tobin received compensation from Eli Lilly for serving on an advisory board and for speaking engagement. Dr. Joshi received compensation from Eli Lilly for serving on an advisory board. Dr. Aurora is an ex-employee of Eli Lilly and Company. All remaining authors are employees and minor stockholders of Eli Lilly and Company or Lilly USA, LLC.

Acknowledgements

Data analyses were performed by Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, IN.

Data sharing statement

Lilly provides access to all individual participant data collected during the trial, after anonymization, with the exception of pharmacokinetic or genetic data. Data are available to request 6 months after the indication studied has been approved in the United States and European Union and after primary publication acceptance, whichever is later. No expiration date of data requests is currently set once data are made available. Access is provided after a proposal has been approved by an independent review committee identified for this purpose and after receipt of a signed data sharing agreement. Data and documents, including the study protocol, statistical analysis plan, clinical study report, blank or annotated case report forms, will be provided in a secure data sharing environment. For details on submitting a request, see the instructions provided at www.vivli.org.

References

- D’Amico D, Grazzi L, Bussone G, et al. Are depressive symptomatology, self-efficacy, and perceived social support related to disability and quality of life in patients with chronic migraine associated to medication overuse? Data from a cross-sectional study. Headache. 2015;55(5):636–645.

- Lanteri-Minet M. Economic burden and costs of chronic migraine. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2014;18(1):385.

- Mao X, Shrestha S, Baser O, et al. A retrospective analysis of the economic burden among patients diagnosed with chronic migraine using the Veterans Health Administration medical data. Value Health. 2015;18(3):A282–A283.

- Aurora SK, Brin MF. Chronic migraine: an update on physiology, imaging, and mechanism of action of two available pharmacologic therapies. Headache. 2017;57(1):109–125.

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The international classification of headache disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia. 2013;33:629–808.

- Weatherall MW. The diagnosis and treatment of chronic migraine. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2015;6(3):115–123.

- Turner DP, Smitherman TA, Penzien DB, et al. Rethinking headache chronification. Headache. 2013;53(6):901–907.

- Schwedt TJ. Chronic migraine. BMJ. 2014;348:g1416.

- May A, Schulte LH. Chronic migraine: risk factors, mechanisms and treatment. Nat Rev Neurol. 2016;12(8):455–464.

- Lipton RB, Silberstein SD. Episodic and chronic migraine headache: breaking down barriers to optimal treatment and prevention. Headache. 2015;55 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):103–122.

- Bigal ME, Serrano D, Buse D, et al. Acute migraine medications and evolution from episodic to chronic migraine: a longitudinal population-based study. Headache. 2008;48(8):1157–1168.

- Buse DC, Manack AN, Fanning KM, et al. Chronic migraine prevalence, disability, and sociodemographic factors: results from the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention Study. Headache. 2012;52(10):1456–1470.

- Raval AD, Shah A. National trends in direct health care expenditures among US adults with migraine: 2004 to 2013. J Pain. 2017;18(1):96–107.

- Linde M, Gustavsson A, Stovner LJ, et al. The cost of headache disorders in Europe: the Eurolight project. Eur J Neurol. 2012;19(5):703–711.

- Martelletti P, Schwedt TJ, Vo P, et al. Healthcare resource use and indirect costs associated with migraine in Italy: results from the My Migraine Voice survey. J Med Econ. 2021;24(1):717–726.

- Negro A, Sciattella P, Rossi D, et al. Cost of chronic and episodic migraine patients in continuous treatment for two years in a tertiary level headache Centre. J Headache Pain. 2019;20(1):120.

- Stovner LJ, Andrée C, Eurolight Steering Committee. Impact of headache in Europe: a review for the Eurolight project. J Headache Pain. 2008;9(3):139–146.

- Goldberg LD. The cost of migraine and its treatment. Am J Manag Care. 2005;11(2 Suppl):S62–S67.

- Tepper D. Medication overuse headache. Headache. 2017;57(5):845–846.

- Shah AM, Bendtsen L, Zeeberg P, et al. Reduction of medication costs after detoxification for medication-overuse headache. Headache. 2013;53(4):665–672.

- Silberstein SD, Holland S, Freitag F, et al. Evidence-based guideline update: pharmacologic treatment for episodic migraine prevention in adults: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society. Neurology. 2012;78(17):1337–1345.

- Diener HC, Solbach K, Holle D, et al. Integrated care for chronic migraine patients: epidemiology, burden, diagnosis and treatment options. Clin Med. 2015;15(4):344–350.

- Blumenfeld AM, Bloudek LM, Becker WJ, et al. Patterns of use and reasons for discontinuation of prophylactic medications for episodic migraine and chronic migraine: results from the Second International Burden of Migraine Study (IBMS-II). Headache. 2013;53(4):644–655.

- Estemalik E, Tepper S. Preventive treatment in migraine and the new US guidelines. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013;9:709–720.

- Ford JH, Schroeder K, Nyhuis AW, et al. Cycling through migraine preventive treatments: implications for all-cause total direct costs and disease-specific costs. JMCP. 2019;25(1):46–59.

- Aurora SK, Dodick DW, Turkel CC, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA for treatment of chronic migraine: results from the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase of the PREEMPT 1 trial. Cephalalgia. 2010;30(7):793–803.

- Stauffer VL, Dodick DW, Zhang Q, et al. Evaluation of galcanezumab for the prevention of episodic migraine: the EVOLVE-1 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75(9):1080–1088.

- Skljarevski V, Matharu M, Millen BA, et al. Efficacy and safety of galcanezumab for the prevention of episodic migraine: results of the EVOLVE-2 phase 3 randomized controlled clinical trial. Cephalalgia. 2018;38(8):1442–1454.

- Detke HC, Goadsby PJ, Wang S, et al. Galcanezumab in chronic migraine: the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled REGAIN study. Neurology. 2018;91(24):e2211–e2221.

- Ford JH, Foster SA, Stauffer VL, et al. Patient satisfaction, health care resource utilization, and acute headache medication use with galcanezumab: results from a 12-month open-label study in patients with migraine. PPA. 2018;12:2413–2424.

- Rothrock JF, Bloudek LM, Houle TT, et al. Real-world economic impact of onabotulinumtoxinA in patients with chronic migraine. Headache. 2014;54(10):1565–1573.

- Negro A, Curto M, Lionetto L, et al. A two years open-label prospective study of onabotulinumtoxinA 195 U in medication overuse headache: a real-world experience. J Headache Pain. 2015;17:1.

- Vikelis M, Argyriou AA, Dermitzakis EV, et al. Sustained onabotulinumtoxinA therapeutic benefits in patients with chronic migraine over 3 years of treatment. J Headache Pain. 2018;19(1):87.

- Tepper S, Ashina M, Reuter U, et al. Safety and efficacy of erenumab for preventive treatment of chronic migraine: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16(6):425–434.

- Halker Singh RB, Aycardi E, Bigal ME, et al. Sustained reductions in migraine days, moderate-to-severe headache days and days with acute medication use for HFEM and CM patients taking fremanezumab: post-hoc analyses from phase 2 trials. Cephalalgia. 2019;39(1):52–60.

- Tepper SJ, Ashina M, Reuter U, et al. Reduction in acute migraine-specific and non-specific medication use in patients treated with erenumab: post-hoc analyses of episodic and chronic migraine clinical trials. J Headache Pain. 2021;22(1):81.

- Tiseo C, Ornello R, Pistoia F, et al. How to integrate monoclonal antibodies targeting the calcitonin gene-related peptide or its receptor in daily clinical practice. J Headache Pain. 2019;20(1):49.

- Friedman BW, West J, Vinson DR, et al. Current management of migraine in US emergency departments: an analysis of the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. Cephalalgia. 2015;35(4):301–309.

- Friedman BW. Managing migraine. Ann Emerg Med. 2017;69(2):202–207.

- Friedman BW, Serrano D, Reed M, et al. Use of the emergency department for severe headache. A population-based study. Headache. 2009;49(1):21–30.

- Blumenfeld AM, Varon SF, Wilcox TK, et al. Disability, HRQoL and resource use among chronic and episodic migraineurs: results from the International Burden of Migraine Study (IBMS). Cephalalgia. 2011;31(3):301–315.

- Bhandari A, Wagner T. Self-reported utilization of health care services: improving measurement and accuracy. Med Care Res Rev. 2006;63(2):217–235.

- Ritter PL, Stewart AL, Kaymaz H, et al. Self-reports of health care utilization compared to provider records. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(2):136–141.

- D'Amico D, Grazzi L, Curone M, et al. Cost of medication overuse headache in Italian patients at the time-point of withdrawal: a retrospective study based on real data. Neurol Sci. 2017;38(Suppl 1):3–6.

- Lantéri-Minet M, Duru G, Mudge M, et al. Quality of life impairment, disability and economic burden associated with chronic daily headache, focusing on chronic migraine with or without medication overuse: a systematic review. Cephalalgia. 2011;31(7):837–850.