Abstract

Aims

To our knowledge, literature describing the place of care and associated costs during acute bipolar I disorder (BP-I) episodes is limited. We conducted a claims-based retrospective study to address this gap.

Materials and methods

Adults with BP-I were identified via IBM MarketScan Commercial and Medicare Supplemental databases. The acute episode index date was defined by ≥1 inpatient BP-I claim(s) or ≥1 outpatient or ≥3 outpatient BP-I claims (depending on visit type) in a 2-week (manic/mixed) or 4-week (depressive) period. Likely acute episodes were defined as 3- and 6-week periods for manic/mixed and depressive episodes, respectively; total mental health-related medical costs (health plan + patient) were collected during these intervals and stratified by setting (inpatient versus outpatient). Initial and subsequent episodes were captured; data were reported in subgroups without and with clozapine use, a proxy for disease severity. The remission index date was the earliest outpatient claim with a bipolar remission diagnosis with no acute episode or treatment. Remission costs were collected over a 3-month period. All results were analyzed descriptively.

Results

A total of 41,516 patients with 130,221 acute manic/mixed episodes and 47,763 patients with 149,207 acute depressive episodes met the study criteria. Over 84% of acute episodes were treated in outpatient settings. Mental health-related medical costs for manic/mixed episodes were $15,444 for inpatient and $1,577 for outpatient settings; inpatient and outpatient costs for depressive episodes were $17,376 and $2,154, respectively. Health plans covered approximately 78% of medical costs for both episode types with and without prior clozapine use. A total of 8,143 patients met remission criteria; the total 3-month outpatient costs were $1,225.

Conclusions

Most BP-I acute manic/mixed or depressive episodes were treated in the outpatient setting. Episodes with inpatient care were 8–10 times more costly than outpatient-only episodes. Health plans covered most medical costs, but additional patient-incurred out-of-pocket costs remained.

Introduction

Bipolar I disorder (BP-I) is a chronic, disabling mental health condition with a 12-month prevalence of 1.5% and a lifetime prevalence of 2.1% in the United States (US)Citation1. The course of illness is characterized by one or more manic episodes and alternating episodes of mania and depression, with depressive episodes occurring 3 times more often than manic episodesCitation2,Citation3. During manic, hypomanic, or depressive episodes, patients with bipolar disorder (BD) may also experience opposite polarity symptoms (i.e. mixed features). Regardless of mood state, BD is a burdensome disease that is associated with significant functional disability, cognitive impairments, and reduced quality of lifeCitation1,Citation4,Citation5. Further, BD imposes a substantial economic burden on the US healthcare systemCitation6–8. The estimated total annual economic burden of BP-I in 2015 was just over $200 billion, with approximately 20% attributed to direct healthcare costs and approximately 70% attributed to indirect healthcare costs, such as reduced productivity, unemployment, and caregivingCitation8. Additionally, evidence suggests that indirect costs associated with productivity loss are significantly higher among patients with BP-I compared with a general population without BD ($4,775 versus $2,548 over the past 12 months; p < .001)Citation9. One study found that patients with BP-I use 3- to 4-fold more healthcare resources and incur over 4-fold greater healthcare costs compared with patients without BDCitation10.

The goal of acute BD treatment is remission, defined as the absence or minimal symptoms of both mania and depression for at least 1 weekCitation11. Several first-line acute treatments are available for manic episodes associated with BP-I, including atypical antipsychotics and mood-stabilizing drugs (e.g. lithium, valproate)Citation12. Currently, the only FDA-approved first-line treatments for bipolar depression are cariprazineCitation13, fluoxetine-olanzapine combinationCitation14, lumateperoneCitation15, lurasidoneCitation16, and quetiapineCitation17. Of these, only cariprazineCitation13 and quetiapineCitation17 are approved in the US to also treat manic/mixed episodes associated with BP-I. Although clozapine is not FDA-approved for any phase of BDCitation18, US-based guidelinesCitation19 provide recommendations for the use of clozapine in resistant BD in acute mania (in combination with a mood stabilizer; Level 3) and as an adjunctive agent for maintenance therapy (Level 3). In general, clozapine is used infrequently (only in about 1.1–1.5% of patients with BD) and is commonly reserved for cases of treatment-resistant BDCitation20,Citation21. For the purpose of this study, clozapine use was considered a proxy for more severe (i.e. treatment-resistant) BP-I.

Though the majority of patients with BD can be managed in the outpatient setting during an acute episodeCitation22,Citation23, inpatient hospitalizations account for approximately 50% of the cost of medical encounters and represent one of the costliest resources used in BDCitation8. In general, inpatient care is reserved for patients who have not responded to prior outpatient treatments or who present with acute symptoms of agitation/aggression and pose a threat to harm themselves or othersCitation22,Citation23. There is limited published literature characterizing the setting utilized on the acute episode level across various BP-I mood episodes and associated costs. An expert panelCitation24 predicted that outpatient care is utilized in 65% of acute manic episodes and 85% of acute depressive episodes in non-hospitalized patients with BD. However, episode-level costs incurred in the inpatient and outpatient settings for acute BP-I episodes are not well described overall.

To our knowledge, no prior study has explicitly examined the place of care and associated costs during BP-I episodes and remission periods. To address this gap, we used a novel methodological approach to identify likely acute BP-I episodes and remission periods using claims data. The objective of this retrospective observational study was to describe the place of care and estimate mental health-related costs associated with acute episodes and untreated remission periods among patients with BP-I.

Methods

Study design

Adults (age ≥18 years) with BP-I were identified using the IBM MarketScan Commercial and Medicare Supplemental databases (January 1, 2009 to December 31, 2018). The Commercial database comprises medical and pharmacy claims for over 225 million unique patients from 300 contributing employers and 40 contributed health plans across the US. The Medicare database contains enrollment and healthcare claims of 6.4 million retirees and disabled persons with Medicare insurance. Neither database includes out-of-network treatments. Patients who were continuously enrolled for at least 12 months prior to and 6 months after the index date were included in the study. Two patient cohorts were evaluated separately: 1) patients in an acute treatment phase (acute episodes), which was further subdivided into manic/mixed versus depressive episodes, and 2) patients in remission, defined in this study as a stable, no treatment phase.

Acute episodes

A novel, claims-based approach was used to identify acute episodes: BP-I diagnosis code (Supplementary Table 1), place of service and frequency, and time period were intentionally selected to identify likely acute BP-I episodes using claims data. Acute episode index date was defined by: ≥1 inpatient bipolar claim(s) or ≥ 1 outpatient claim(s) at an urgent care facility, outpatient hospital (on campus), emergency room (hospital), skilled nursing facility, nursing facility, ambulance (land), comprehensive inpatient or outpatient rehabilitation facility or ≥ 3 outpatient claims on 3 distinct days within a 2-week (manic/mixed) or 4-week (depressive) period at a pharmacy, telehealth, office, patient or group home, assisted living facility, outpatient hospital (off campus), custodial care facility, independent clinic, federally qualified health center, psychiatric facility partial hospitalization, community mental health center, intermediate care/intellectual disability, residential or non-residential substance abuse facility, psychiatric residential treatment center, state/local public health clinic, rural health clinic, or outpatient (not elsewhere classified); the first claim was defined as the index date. In addition, patients were required to have ≥1 inpatient or outpatient claim with a bipolar diagnosis in any position and ≥2 prescriptions for an atypical antipsychotic (i.e. aripiprazole, asenapine, brexpiprazole, cariprazine, clozapine, fluoxetine hydrochloride/olanzapine, iloperidone, lurasidone, olanzapine, paliperidone, pimavanserin, quetiapine, risperidone, ziprasidone) or other bipolar treatment (i.e. lithium, olanzapine-fluoxetine, carbamazepine, valproate [divalproex and valproic acid], lamotrigine, electroconvulsive therapy) in the baseline period. For acute episodes of each type (manic/mixed or depressive), the main cohort (all patients) was evaluated as well as subgroups of patients without or with prior clozapine use (defined as the presence of ≥2 prescriptions for clozapine in the baseline period on separate days). The use of clozapine, which is typically reserved for treatment-resistant BD, was used as an indication of greater disease severity.

Remission periods

The remission index date was defined by ≥1 outpatient claim with a BP-I remission diagnosis with no acute episode and no oral or injectable atypical antipsychotic or other bipolar treatment claims in the 6-month follow-up period. Patients included in this cohort were also required to have ≥1 inpatient or outpatient claim with a BP-I diagnosis in any position anytime during the baseline period.

Outcomes and analysis

Demographics and baseline characteristics were assessed descriptively. Place of care (inpatient versus outpatient) and details pertaining to the length of stay and number of episodes were summarized descriptively for acute episodes. Direct mental health-related medical and pharmacy costs (identified by coding and adjusted to 2019 values) associated with place of care for acute episodes (inpatient and outpatient) and during remission were assessed. Only non-capitated costs were included in the analysis. For acute episodes, total costs were the sum of medical costs and pharmacy costs, which were additionally classified by the following medication subgroups: oral atypical antipsychotics, non-oral antipsychotics, typical antipsychotics, other bipolar treatments (e.g. lithium, olanzapine-fluoxetine, carbamazepine, valproate [divalproex and valproic acid], lamotrigine, electroconvulsive therapy), and other mental health medications (i.e. excluding all antipsychotics and other bipolar treatments). For acute episodes, all mental health-related costs were included for an observation period starting at the inpatient admission date and continuing for 3 weeks (manic/mixed) or 6 weeks (depressive) post-episode start (e.g. inpatient stay and corresponding follow-up) or at first qualifying outpatient claim and continuing for 2 weeks (manic/mixed) or 4 weeks (depressive). For periods of remission, total costs were the sum of medical costs and all pharmacy costs (excluding oral or injectable typical and atypical antipsychotics and other bipolar treatments), which were captured during the 3 months post-index. Data were analyzed descriptively and presented as means for the total payment to the provider (health plan + patient) and health plan-only payment to the provider.

Results

Patient selection

A total of 41,516 patients with manic/mixed acute episodes and 47,763 patients with depressive episodes met the selection criteria (Supplemental Figure 1). The vast majority (∼99%) did not have prior clozapine use. A total of 8,143 patients met the criteria for a period of remission (Supplemental Figure 2).

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics

Demographics and baseline patient characteristics at the index date were generally similar between groups () and between the without and with prior clozapine cohorts (Supplemental Table 2). The average age was early-to-mid 40 s, and most patients were female. Approximately 90% of patients were on commercial insurance, and over 50% of patients were on preferred provider organization health plans.

Table 1. Patient demographics and baseline characteristics.

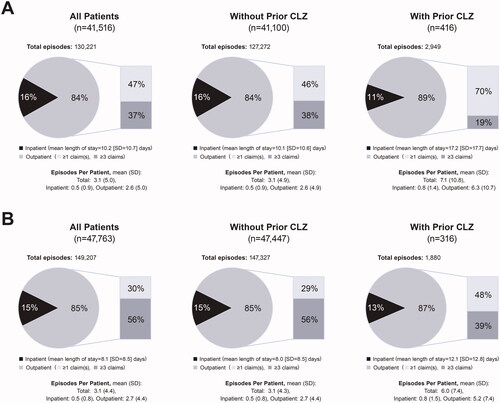

Acute episodes place of care

Regardless of episode type or prior clozapine use, most acute episodes (84%–89%) were treated in an outpatient setting (). For manic/mixed acute episodes, mean (SD) episodes per patient were 3.1 (5.0) for all patients, 3.1 (4.9) without prior clozapine use, and 7.1 (10.8) with prior clozapine. The mean (SD) length of stay when hospitalized was 10.2 (10.7) days for all patients, 10.1 (10.6) days without prior clozapine use, and 17.2 (17.7) days with prior clozapine. For depressive acute episodes, mean (SD) episodes per patient were 3.1 (4.4) for all patients, 3.1 (4.3) without prior clozapine use, and 6.0 (7.4) with prior clozapine use. The mean (SD) length of stay when hospitalized was 8.1 (8.5) days for all patients, 8.0 (8.5) days without prior clozapine use, and 12.1 (12.8) days with prior clozapine use.

Costs

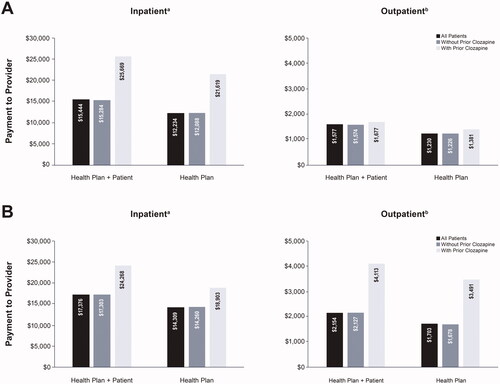

Acute episodes

Total mental health-related inpatient and outpatient medical costs (health plan + patient) were similar for manic/mixed and depressive acute episodes (). Mean total inpatient costs (SD) were $15,444 ($18,336) for manic/mixed episodes and $17,376 ($21,515) for depressive episodes; mean total outpatient health costs were $1,577 ($5,186) for manic/mixed episodes and $2,154 ($7,083) for depressive episodes. For patients with manic/mixed episodes without prior clozapine use, mean total inpatient costs were $15,284 ($18,128) (health plan=$12,088 [$16,488]); mean total outpatient costs were $1,574 ($5,146) (health plan=$1,226 [$4,396]). For those with prior clozapine use for manic/mixed episodes, mean total inpatient costs were $25,669 ($26,844) (health plan=$21,619 [$26,550]); mean total outpatient costs were $1,677 ($5,955) (health plan=$1,381 [$5,664]). For those with depressive episodes without clozapine use, mean total inpatient costs were $17,303 ($21,428) (health plan=$14,260 [$19,850]); mean total outpatient costs were $2,127 ($6,206) (health plan=$1,678 [$5,579]). For those with clozapine use for depressive episodes, mean total inpatient costs were $24,268 ($27,734) (health plan=$18,903 [$21,982]); mean total outpatient costs were $4,113 ($30,090) (health plan=$3,491 [$29,393]). Across all patients and episode types, health plans covered approximately 78% or more of medical costs; patient-incurred out-of-pocket medical costs were around 20%, regardless of setting or acute episode type.

Figure 2. Acute mental health-related medical costs for (A) manic/mixed acute episodes and (B) depressive acute episodes of bipolar I disorder.

aInpatient medical costs include claims during an inpatient stay and include a 3-week (manic/mixed) or 6-week (depressive) observation period post-episode start.

bOutpatient medical costs include physician visits, lab visits, and other outpatient visits during a 2-week (manic/mixed) or 4-week (depressive) observation period for identifying outpatient claims.

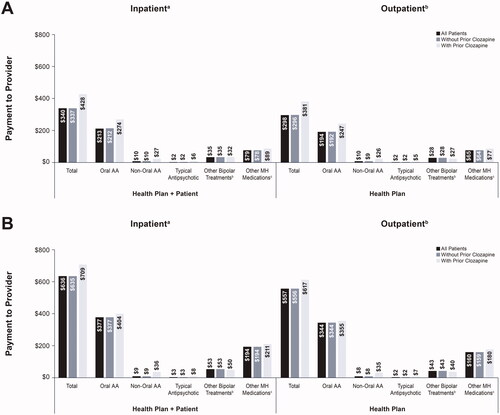

Pharmacy

Total mental health-related pharmacy costs during acute episodes were numerically higher for depressive acute episodes than in manic/mixed episodes (). The mean total pharmacy costs for manic/mixed episodes were $340 for all patients, $337 for patients without prior clozapine use, and $428 for those with prior clozapine use. For both episode types and all patients, health plans generally covered >80% of pharmacy costs. Patient-incurred out-of-pocket total pharmacy costs were approximately 12% in both acute manic and depressive episodes.

Figure 3. Mental health-related pharmacya costs for (A) manic/mixed acute episodes and (B) depressive acute episodes of bipolar I disorder.

aPharmacy costs are for both inpatient and outpatient episode types.

bIncludes lithium, olanzapine-fluoxetine, carbamazepine, valproate (divalproex and valproic acid), lamotrigine, and electroconvulsive therapy.

cOther mental health medications (listed in Supplemental Table 3) are for pharmacy fills excluding antipsychotics (atypical and typical) and other bipolar treatments. Abbreviations. AA, atypical antipsychotic; MH, mental health.

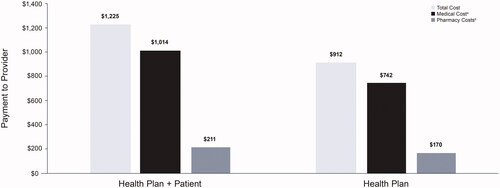

Remission

The 3-month mean outpatient mental health-related costs for patients with a period of remission were $1,225 (health plan + patient) and $912 for health plan only (). The bulk of these costs was for medical visits (>80%).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to estimate costs and place of care associated with acute BP-I episodes and remission periods, refining our understanding of the location of care and the associated costs. Overall, the majority of acute episodes (>84%) in patients with BP-I were treated in the outpatient setting. This finding is higher than the previously reported expert panel prediction for the outpatient treatment of acute manic episodes (3 weeks)—only 65%—but is consistent with their 85% prediction in acute depressive episodes (6 weeks) in non-hospitalized patientsCitation24. Inpatient length of stay and the percentage of episodes treated in the outpatient setting were generally similar among those with manic mixed/episodes and depressive episodes.

Mean mental health-related medical costs associated with depressive episodes were generally higher than costs associated with manic/mixed episodes. Evidence suggests that the depressive phase is the more disabling feature of BDCitation25, which may have contributed to the higher costs observed in our study. In addition, the differences may be attributed to the longer observation period for depressive episodes (inpatient: 6 weeks; outpatient: 4 weeks) than for manic/mixed episodes (inpatient: 3 weeks; outpatient: 2 weeks). However, these results are descriptive, and analyses to formally compare costs between episode types were not conducted. Mental health-related medical costs were 8–10 times higher for episodes requiring inpatient care than for outpatient-only episodes. However, the outpatient-only episode costs were substantial and should be considered when determining the cost of acute episodes. Costs were higher in patients with clozapine use, likely reflecting its use in more severe BP-I. Regardless of the setting, mental health-related pharmacy costs associated with acute BP-I episodes were considerably lower than medical costs. Approximately 60% of pharmacy costs for acute mania and depression were for atypical antipsychotics, which are commonly prescribed in patients with BP-I. Other non-antipsychotic medications (e.g. lithium, mood stabilizers) accounted for approximately 8% of pharmacy costs for depressive episodes and 10% for manic/mixed episodes. During remission, medical visits accounted for the majority (>80%) of the 3-month outpatient total costs. Health plans covered the majority of medical and pharmacy costs of both acute episodes and remission periods; however, patient-incurred out-of-pocket costs remained.

Inpatient services represent a considerable portion of the economic burden associated with BD. In this descriptive analysis, the costs of episodes with inpatient care were approximately 10 times higher than outpatient-only costs for acute manic/mixed episodes and approximately 8 times higher than outpatient-only costs for acute depressive episodes. This finding aligns with previous studies reporting that hospitalization in patients with BD is the costliest resource and contributes to approximately 33% to 66% of overall costsCitation8,Citation26. Because most patients with BP-I require at least 1 hospitalization during their lifetimeCitation26, strategies that prevent hospitalization should be explored to ease this economic burden and improve clinical outcomes. For example, medication nonadherence, which has been linked to greater use of inpatient resourcesCitation27, is common in BDCitation28, and the use of medications with better tolerability profiles may reduce nonadherence and minimize the high costs associated with inpatient care. Future research is needed to identify effective strategies to improve care and reduce costly inpatient services among patients with BP-I.

This study is the first of its kind to estimate mental health-related costs and setting according to acute BP-I episodes. Novel methods were used to identify likely acute episodes using claims data, which present certain methodological challenges. For example, it is difficult to discern whether a patient is experiencing an acute episode using claims data due to the lack of documented clinical assessments. To mitigate these challenges, the type of procedure and diagnosis code, frequency, and time period were intentionally selected prior to the start of the study. Despite their limitations, claims data contain useful information for evaluating costs and setting associated with acute BP-I episodes.

The results of this study should be interpreted within its limitations, most of which are inherent to claims database analyses. Analysis was limited to individuals with commercial or Medicare coverage; therefore, the results may not be generalizable to patients with other types of insurance (e.g. Medicaid) or no insurance. Additionally, a minimum coverage period was required, which may have contributed to selection bias. As with claims data, there is potential for data coding and/or entry errors. Also, out-of-network treatments for BP-I were not captured in these databases. The sample size of patients with prior clozapine use was small and contributed to <1% of the total patient population; therefore, comparisons between the cohorts without and with prior clozapine use should be interpreted with caution. Data surrounding the use of clozapine in combination with a mood stabilizer were not collected. Clozapine was only used as a proxy for disease severity in this study; episode type was determined using ICD codes. Although used infrequently in patients with BP-I, recent evidence suggests that clozapine may benefit patients with either manic or depressive symptomsCitation21. In addition, as remission may be underreported in claims, it is possible that the number of patients in remission during this study was conservative. Finally, it was not known for certain whether a patient was experiencing an acute episode since proxy measures (diagnosis codes and visits) were used due to limited available claims information classifying events as part of such episodes; periods of remission were also identified via a proxy measure. While these proxies were discussed with and approved by all investigators, it is possible that they did not capture the full nature of BP-I episodes and periods of remission.

In conclusion, the results of this novel study indicate the majority of acute BP-I episodes were treated in the out patient setting. Episodes that required inpatient care were approximately 10 times more costly than outpatient-only episodes. Patients with prior clozapine use had greater costs than patients without prior clozapine use. Health plans covered the majority of mental health-related medical and pharmacy costs, though some patient-incurred out-of-pocket costs remained. This study is the first to estimate the setting and costs of acute BP-I episodes, advancing our understanding of the locus of BP-I care and its cost to the healthcare system.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was sponsored by Allergan plc (prior to its acquisition by AbbVie).

Declaration of financial/other relationships

RM has received research grant support from CIHR/GACD/National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC); speaker/consultation fees from Lundbeck, Janssen, Alkermes, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Purdue, Pfizer, Otsuka, Takeda, Neurocrine, Sunovion, Bausch Health, Novo Nordisk, Kris, Sanofi, Eisai, Intra-Cellular, NewBridge Pharmaceuticals, AbbVie, Atai Life Sciences. RM is a CEO of Braxia Scientific Corp. SH was an employee of AbbVie at the time of the study. QVD, DA, DO are employees of Genesis Research, which was contracted to perform the study. PG is an employee of AbbVie and may hold stock. AH was an employee of AbbVie at the time of the study and may hold stock. All authors met the ICMJE authorship criteria. Neither honoraria nor payments were made for authorship.

Author contributions

DA, QVD, AH, SH, PG, and DO contributed to study conception and design, collection and assembly of data, and data analysis and interpretation. RM contributed to study conception and design, data analysis and interpretation. All authors reviewed and approved the final content of this manuscript and are accountable for all aspects of the work.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (122.1 KB)Acknowledgements

Writing and editorial assistance were provided to the authors by Susan Bartko-Winters, PhD, and Caroline Warren, PharmD, of Prescott Medical Communications Group (Chicago, IL), a contractor of AbbVie.

Data availability statement

This study was exempt from Ethics Committee approval and institutional review because it is a retrospective analysis that used anonymized and de-identified data certified as fully compliant with United States patient confidentiality requirements set forth in the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996. Allergan (prior to its acquisition by AbbVie) obtained permission to access and use the IBM MarketScan data used in the analysis through licensing agreements.

References

- Blanco C, Compton WM, Saha TD, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 bipolar I disorder: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions – III. J Psychiatr Res. 2017;84:310–317.

- Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, et al. The long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(6):530–537.

- McIntyre RS, Berk M, Brietzke E, et al. Bipolar disorders. Lancet. 2020;396(10265):1841–1856.

- Bonnin CDM, Reinares M, Martinez-Aran A, et al. Improving functioning, quality of life, and well-being in patients with bipolar disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2019;22(8):467–477.

- Khafif TC, Belizario GO, Silva M, et al. Quality of life and clinical outcomes in bipolar disorder: an 8-year longitudinal study. J Affect Disord. 2021;278:239–243.

- Dilsaver SC. An estimate of the minimum economic burden of bipolar I and II disorders in the United States: 2009. J Affect Disord. 2011;129(1–3):79–83.

- Bessonova L, Ogden K, Doane MJ, et al. The economic burden of bipolar disorder in the United States: a systematic literature review. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2020;12:481–497.

- Cloutier M, Greene M, Guerin A, et al. The economic burden of bipolar I disorder in the United States in 2015. J Affect Disord. 2018;226:45–51.

- Culpepper L, Higa S, Martin A, et al. Reduced health-related quality of life and increased costs associated with bipolar I disorder. Poster presented at the Psych Congress. San Antonio, TX; 2021.

- Bryant-Comstock L, Stender M, Devercelli G. Health care utilization and costs among privately insured patients with bipolar I disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2002;4(6):398–405.

- Hirschfeld RM, Calabrese JR, Frye MA, et al. Defining the clinical course of bipolar disorder: response, remission, relapse, recurrence, and roughening. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2007;40(3):7–14.

- Rolin D, Whelan J, Montano CB. Is it depression or is it bipolar depression? J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2020;32(10):703–713.

- Allergan. Vraylar® (cariprazine) prescribing information. Madison (NJ); 2019.

- Deeks ED, Keating GM. Spotlight on olanzapine/fluoxetine in acute bipolar depression. CNS Drugs. 2008;22(9):793–795.

- Intra-Cellular Therapies Announces US FDA Approval of Caplyta (lumateperone) for the Treatment of Bipolar Depression in Adults. Intra-Cellular Therapies. [cited 2021 Dec 20]. Available from: https://ir.intracellulartherapies.com/news-releases/news-release-details/intra-cellular-therapies-announces-us-fda-approval-caplytar.

- Alembic Pharmaceuticals. Lurasidone hydrochloride prescribing information. Bridgewater (NJ); 2019.

- ACI Healthcare. Quetiapine extended release prescribing information. Cora Springs (FL); 2021.

- Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation. Clozaril® prescribing information. East Hanover (NJ); 2014.

- Florida Medicaid Drug Therapy Management Program for Behavioral Health, University of South Florida College of Behavioral & Community Sciences. Psychotherapeutic Medication Guidelines for Adults 2019-2020. Agency for Health Care Administration State of Florida; 2019. Available from: https://floridabhcenter.org/.

- Wilkowska A, Cubała WJ. Clozapine as transformative treatment in bipolar patients. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019;15:2901–2905.

- Costa MH, Kunz M, Nierenberg AA, et al. Clozapine and the course of bipolar disorder in the systematic treatment enhancement program for bipolar disorder (STEP-BD): La clozapine et l’évolution du trouble bipolaire dans le programme d’amélioration systématique du traitement du trouble bipolaire (STEP-BD). Can J Psychiatry. 2020;65(4):245–252.

- Shah N, Grover S, Rao GP. Clinical practice guidelines for management of bipolar disorder. Indian J Psychiatry. 2017;59(Suppl 1):S51–S66.

- Al Jurdi RK, Schulberg HC, Greenberg RL, et al. Characteristics associated with inpatient versus outpatient status in older adults with bipolar disorder. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2012;25(1):62–68.

- Begley CE, Annegers JF, Swann AC, et al. The lifetime cost of bipolar disorder in the US: an estimate for new cases in 1998. Pharmacoeconomics. 2001;19(5 Pt 1):483–495.

- Miller S, Dell’Osso B, Ketter TA. The prevalence and burden of bipolar depression. J Affect Disord. 2014;169(Suppl 1):S3–S11.

- Bergeson JG, Kalsekar I, Jing Y, et al. Medical care costs and hospitalization in patients with bipolar disorder treated with atypical antipsychotics. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2012;5(6):379–386.

- Ascher-Svanum H, Faries DE, Zhu B, et al. Medication adherence and long-term functional outcomes in the treatment of schizophrenia in usual care. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(03):453–460.

- Chakrabarti S. Treatment-adherence in bipolar disorder: a patient-centred approach. World J Psychiatry. 2016;6(4):399–409.