Abstract

Aims

Using a national electronic health records (EHR) database, the current study describes treatments, depression severity, and health care resource utilization (HRU) among patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) and acute suicidal ideation or behavior (MDSI) prior to, during, and following a suicide-related event in the United States.

Materials and methods

This retrospective matched cohort study used data collected from the Optum EHR de-identified database for patients with diagnosis codes for MDD and acute suicidal ideation or behavior and a propensity score–matched cohort of patients without MDD or a suicide-related event. The study period was 31 October 2015–30 September 2019. MDD-related treatments and 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) scores, when available, were assessed at the first health care encounter for a suicide-related event (index period), 12 months before (pre-period), and 6 months after (post-period). All-cause and MDD-related HRU were assessed during the post-period.

Results

The mean (standard deviation) age of patients with MDSI was 39 (16) years; 55.0% were female. Index events occurred as follows: inpatient stay, 38.9%; observation unit stay, 4.6%; emergency department (ED) visit, 46.5%; and outpatient visit, 10.1%. Antidepressants and psychotherapy were the most common pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatments, respectively, prescribed during the pre- (31.3%, 9.5%, respectively) and index (41.2%, 18.7%, respectively) periods. Post-period data (n = 40,261) revealed only 43.4% received an antidepressant and 20.5% had psychotherapy after the suicide-related event. Few patients had PHQ-9 scores recorded during the pre- (4.4%), index (1.3%), and post- (7.6%) periods. During the post-period, 11.8%, 5.0%, and 33.1% of patients had ≥1 all-cause inpatient stay, observation unit stay, and ED visit, respectively; 61.0% had ≥1 all-cause and 33.4% ≥1 MDD-related outpatient visit. Most patients with MDSI and an inpatient encounter or ED visit were discharged to home or self-care (65.4%). Odds of an all-cause hospital encounter during the post-period were higher for patients with versus without MDSI (by 30.1, 33.5, and 33.9 times for inpatient stay, ED visit, and observation unit stay, respectively).

Conclusion

This analysis highlights an opportunity to improve outcomes for this vulnerable population. More complete data on patient outcomes is needed to inform strategies designed to optimize screening and treatment.

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is among the most common mood disorders, with depression being the leading cause of disability worldwideCitation1–3. An estimated 19.4 million adults in the United States in 2019 had ≥1 major depressive episode (MDE) in the past year, representing approximately 7.8% of the adult population; of these, nearly two-thirds had an MDE with severe impairmentCitation4. Particularly severe symptoms, including acute suicidal ideation or behavior, place some patients with MDD at increased risk of poor outcomesCitation5. In 2018, 32.0% of adults with MDD reported serious thoughts of suicide, 11.7% reported a suicide plan, and 4.6% reported a suicide attemptCitation6. The total economic burden of MDD in the United States is substantial, estimated at $326.2 billion in 2018, including direct medical costs, absenteeism and presenteeism, and lost lifetime earnings due to suicideCitation7. Health systems often struggle with providing adequate care for mental health disorders, such as MDD, and there is a need to improve both continuity of care and the patient experienceCitation8,Citation9.

Empirical studies focused on clinical and economic burden of patients with MDD and acute suicidal ideation or behavior (MDSI) have recently been reported using different databases covering different populations, such as the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) system datasetCitation10, OptumHealth Care Solutions, Inc. databaseCitation11, Premier Hospital databaseCitation12, and online patient community platform, PatientsLikeMeCitation13. The findings from these analyses suggest the need for better care, better screening, and more efficacious treatment of MDSI. However, to our knowledge, this is the first study focused on this population receiving care in the integrated delivery network (IDN) setting. Electronic health record (EHR) data potentially offer advantages in the study of conditions like MDD because, in addition to records of outpatient visits, hospitalizations, diagnostic procedures, medications, and laboratory results, they may contain useful information in the clinical notes, including patient-reported outcomes data. One measure of depression captured in the EHR of particular interest to this patient population is the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). The PHQ-9, a patient self-reported instrument, is aligned with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) symptom criteria for MDD and has been validated as a standardized tool to screen for depressive disorders and to measure depression symptom severity and treatment responseCitation14. The PHQ-9 has shown high accuracy, with sensitivity and specificity of 61.5–92% and 82–88%, respectivelyCitation15–17, compared with semi-structured diagnostic interviews for MDD. In 2016, the PHQ-9 was endorsed as a quality measure by the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) for inclusion in NCQA Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) measuresCitation14,Citation18. Therefore, HEDIS should incentivize its use and collection. In this study, PHQ-9 was used as a tool to measure depression symptom severity from unstructured data derived from the EHR database.

The purpose of the current study was to leverage a national EHR database to describe treatments, depression severity, and health care resource utilization (HRU) prior to, during, and following a suicide-related event among patients with MDSI. A more complete understanding of the treatment progression and HRU of this patient population may help to identify opportunities to improve treatment pathways and outcomes.

Methods

Study design and data source

This was a retrospective, matched cohort study that used data from the Optum de-identified EHR database. The Optum EHR database is a longitudinal patient-level medical record of >100 million patients treated at >700 hospitals and >7,000 clinics across the United States. This study analyzed data from adult patients (≥18 years of age) enrolled in an IDN (approximately 80% of the full dataset) in order to capture the continuum of care from ambulatory to inpatient/facility settings. Patients from a non-IDN were excluded to avoid missing data from incomplete records. During the study period (31 October 2015–30 September 2019), patients were followed from the index date (defined as the first occurrence of a diagnosis code for acute suicidal ideation or behavior) to the earliest of the following occurrences: death, end of health care activity in the dataset, or end of data availability. Acute suicidal ideation or behavior was defined by International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) codes for (1) suicidal ideation, (2) suicide attempt, or (3) intentional self-harm suggestive of suicidal behavior, based on the coding classification in Hedegaard et al. (Supplementary Appendix 1)Citation19. To increase the likelihood that intentional self-harm events were reflective of suicidal behavior, a suicidal ideation diagnosis code was required to be observed on the index date or within 6 months post-index. All patient data contained in the Optum EHR database were de-identified and in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. Since this study consisted of secondary data analyses of de-identified patient records, the study was exempt from institutional review board approval.

Patient and public involvement

No patient involved.

Study cohorts

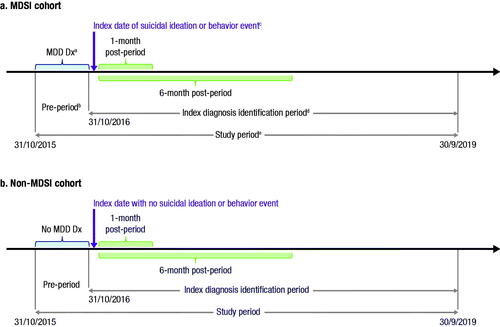

Patients were categorized into two mutually exclusive cohorts (MDSI and non-MDSI) based upon study-defined criteria. The study design incorporated a study period, pre-index period, index diagnosis identification period, and post–index event period (). Patients within the MDSI cohort met the following criteria:

Within the study period, ≥1 diagnosis for MDD as defined using the ICD-10-CM codes F32 and F33. Codes specific for F32.8 (other depressive episodes) and F33.8 (other recurrent depressive disorders) were excluded.

Within the index period, ≥1 diagnosis code indicating acute suicidal ideation or behavior between 31 October 2016 and 30 September 2019 (Supplementary Appendix 1). The date of the first code for suicidal ideation or behavior determined the index date. Only those events with evidence of health care activity ≥12 months prior to the index date and within the study period were included.

Within the 12 months prior to or on the index date (pre-period), ≥1 diagnosis for a depressive disorder (ICD-10-CM: F32, F33, F34.1, F43.21), and no diagnosis for bipolar or related disorders, mania, dementia, intellectual disability, schizophrenia, schizotypal, delusional, or other nonmood psychotic disorders during the study period.

Figure 1. Study design. (a) MDSI cohort. (b) Non-MDSI cohort. Abbreviations: MDSI, major depressive disorder and acute suicidal ideation or behavior; MDD, major depressive disorder; Dx, diagnosis. a≥1 diagnosis for MDD or other depressive disorder within the 12 months prior to or on the index date. b≥12 months of health care activity prior to the index period. cThe date of the first occurrence of suicidal ideation is defined as the index date and could occur any time within the index period. d≥1 diagnosis code for acute suicidal ideation or behavior during 31 October 2016 to 30 September 2019. e≥1 diagnosis for a depressive disorder during the study period.

The non-MDSI cohort was chosen to be the comparative cohort as a reflection of the general population without the condition of the case cohort (i.e. MDSI) and was constructed in two steps. First, the index date of each patient in the MDSI cohort was used to select a sample of patients (100 per each patient in the MDSI cohort) with health care activity documented on that same date who also met the following criteria:

No diagnosis indicating MDD or acute suicidal ideation or behavior at any time during the study period.

No diagnosis for a depressive disorder on or within 12 months prior to their index event, and ≥12 months of health care activity prior to the index event (pre-period).

No diagnosis for bipolar or related disorders, mania, dementia, intellectual disability, schizophrenia, schizotypal, delusional, or other nonmood psychotic disorders during the study period.

Due to the nonrandomized nature of this noninterventional study, comparisons of HRU between these two cohorts may be confounded by differences in the populations at baseline. Thus, a statistical procedure was employed to minimize the potential influence of this issue on the comparisons and focus on economic differences arising from differences in clinical characteristics. Specifically, patients in the MDSI cohort were matched to patients in the non-MDSI cohort using a 1:1 propensity score–matching method to balance differences in patient demographics, regional trends in care, and changes in care over time among the two cohortsCitation11,Citation20–22. The propensity score was defined as the probability of being in the MDSI cohort versus the non-MDSI cohort and was estimated using a logistic regression model based on the following baseline characteristics as covariates: age group, sex, race, ethnicity, insurance type, geographic region, geographic division, and the year of index date. Any characteristics related to the state of health were excluded from the propensity score matching. A patient with MDSI was matched to a patient without MDSI whose propensity score was closest to that of the patient with MDSI. Once a patient without MDSI was matched to a patient with MDSI, that patient without MDSI was no longer eligible for consideration as a match for other patients with MDSI. Balance on baseline covariates was assessed with standardized differences, with an absolute standardized difference ≥0.1 chosen as the threshold for potentially meaningful imbalanceCitation23.

Outcome measures

Patient demographics and insurance type were assessed for both the MDSI and non-MDSI cohorts during the 12 months prior to the index date (pre-period) and were used in the statistical matching procedure. Mental health comorbidities (based on the DSM-5) were also evaluated during the pre-period and compared between the MDSI and non-MDSI cohortsCitation24.

The use of MDD-related pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic therapies was assessed for the MDSI cohort during the pre-period, index period, 1-month post-period, and 6-month post-period. MDD-related pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic therapies, obtained from prescription and procedure records, respectively, were summarized into the following categories: use of antidepressants (i.e. selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, serotonin modulators, norepinephrine-serotonin modulators, tricyclic and tetracyclic antidepressants, miscellaneous antidepressants, and monoamine oxidase inhibitors), adjunctive treatments for MDD (i.e. anticonvulsants/mood stabilizers, atypical/second-generation antipsychotics, psychostimulants, thyroid hormone, buspirone, and lithium), other psychotherapeutic drugs (e.g. benzodiazepines), and use of nonpharmacologic therapy (i.e. psychotherapy, transcranial magnetic stimulation, electroconvulsive therapy, and vagus nerve stimulation).

PHQ-9 scores were used to categorize depression symptom severity and were obtained (if available) from unstructured data derived from the EHR note fields using Optum’s proprietary natural language processing algorithm. Among patients in the MDSI cohort with PHQ-9 scores recorded in their medical records, the scores were evaluated during the pre-period, index period, and 6-month post-period. Severity categories were defined as: none/minimal, score of 0–4; mild, 5–9; moderate, 10–14; moderately severe, 15–19; and severe, 20–27Citation15. For patients with multiple PHQ-9 scores during a period, only the most recent one during a period was used. Among patients with ≥2 PHQ-9 score records (one during the pre-period and another during the 6-month post-period), the change in depression severity was calculated.

All-cause and MDD-related HRU were reported by category (i.e. inpatient stay, observation unit stay, emergency department [ED] visit, and outpatient visit) and assessed during the 1-month post-period and 6-month post-period. The same four categories were used to describe the care setting of the index event. Using patient discharge codes, discharge disposition was examined for those patients in the MDSI cohort with an index care setting of inpatient stay, observation unit stay, or ED visit.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were represented using means and standard deviations (SDs), and categorical variables were represented with counts and percentages. Differences in proportions of categorical variables were assessed using Chi-square tests. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS Enterprise Guide, version 7.1.

Odds ratios (ORs) generated using a logistic regression model were used to compare the proportion of patients with ≥1 encounter of all-cause or MDD-related HRU between the MDSI and non-MDSI cohorts.

Results

Patient demographics and mental health comorbidities

A total of 71,161 patients with MDSI were included in this analysis. The mean (SD) age was 39 (16) years, and 55.0% of patients were female. Index events were distributed across health care settings as follows: inpatient stay, 38.9%; observation unit stay, 4.6%; ED visit (with no inpatient admission), 46.5%; and outpatient visit, 10.1%. Propensity score matching yielded a well-matched non-MDSI cohort (, Supplementary Appendix 2).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics in the MDSI cohort, matched non-MDSI cohort, and standard differences in propensity score–matched cohorts.

Among patients with MDSI, the most common DSM-5–related comorbidity during the pre-period was anxiety disorder (30.3%). The top 10 most prevalent pre-period mental health comorbidities (based on the MDSI cohort) are presented in Supplementary Appendix 3; all comorbidities were significantly more common among patients in the MDSI cohort than among those in the non-MDSI cohort (all p <0.0001).

Pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic therapies

Among patients in the MDSI cohort, antidepressants were the most prescribed medication during the pre-period (31.3%), index period (41.2%), 1-month post-period (29.1%), and 6-month post-period (43.4%), with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors being the most prescribed antidepressant across time periods ().

Table 2. Depression and other mental health–related treatments recorded for patients with MDSI.

Atypical antipsychotics indicated for adjunctive use in MDD were the most commonly prescribed augmentation agents during the pre-period (5.2%), index period (14.1%), 1-month post-period (6.8%), and 6-month post-period (10.8%). The proportions of patients receiving nonpharmacologic therapy were lower than the proportions prescribed pharmacologic therapy, with psychotherapy being the most common nonpharmacologic therapy (ranging from 9.5% of patients during the pre-period to 20.5% of patients during the 6-month post-period).

PHQ-9 scores

Overall, very few patients in the MDSI cohort had PHQ-9 scores recorded during the pre-period, index period, and 6-month post-period (4.4%, 1.3%, and 7.6%, respectively; ).

Table 3. PHQ-9 scores for the MDSI cohorta.

Less than 2% of patients (n = 1,139) had PHQ-9 scores during both the pre-period and 6-month post-period ().

Table 4. Shifts in PHQ-9 score categories for patients with MDSI with scores during pre- and 6-month post-periods (n = 1,139)a.

Among these patients, 22.7%, 21.1%, and 23.0% had moderate, moderately severe, and severe depression, respectively, during the pre-period. Of note, although 61.1% of patients with severe depression during the pre-period shifted to a less severe level of symptomatology during the 6-month post-period, 38.9% remained in the severe range.

HRU

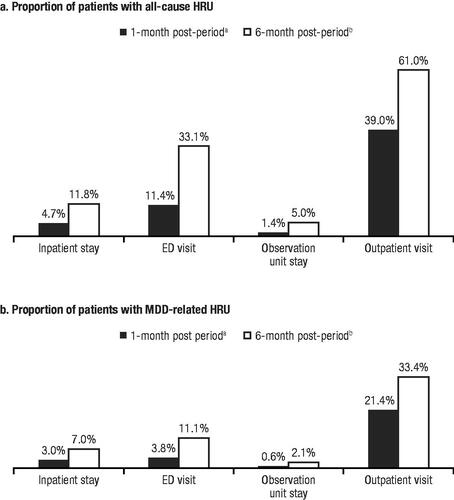

For patients in the MDSI cohort (n = 40,261), 61.0% of patients had an all-cause HRU in the outpatient setting 6 months after a suicide-related event, whereas 33.4% of patients had an MDD-related HRU in the same period (). Notably, that leaves 39% of patients without an outpatient visit 6 months following a suicide-related event. Visits to the ED 6 months after an event were less frequent but still high, with 33.1% of patients having an all-cause HRU in the ED and 11.1% of patients having an MDD-related HRU. Inpatient stays were similar between the two groups, with 11.8% and 7.0% of patients having an all-cause or MDD-related HRU after a suicide-related event, respectively.

Figure 2. Post-period HRU in the MDSI cohort. (a) Proportion of patients with all-cause HRU. (b) Proportion of patients with MDD-related HRU. Abbreviations: HRU, health care resource utilization; MDSI, major depressive disorder and acute suicidal ideation or behavior; ED, emergency department; MDD, major depressive disorder. aHRU reported for the 57,058 patients in the MDSI cohort with ≥1 month of data in the post-period. bHRU reported for the 40,261 patients in the MDSI cohort with ≥6 months of data in the post-period.

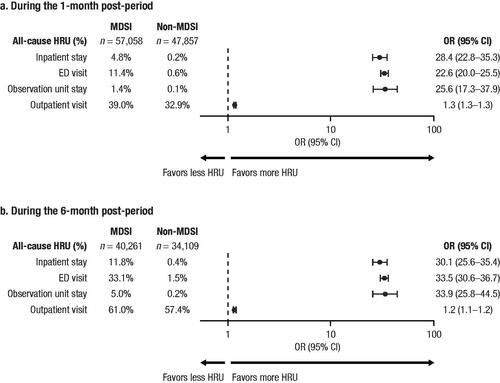

Compared to those in the non-MDSI cohort (n = 34,109), patients in the MDSI cohort (n = 40,261) had higher odds of an all-cause hospital encounter during the 6-month post-period (). Specifically, the OR of an inpatient admission, ED visit, or observation unit stay during the 6-month post-period was 30.1, 33.5, and 33.9 for MDSI versus non-MDSI, respectively, compared with 1.2 for an outpatient visit.

Figure 3. All-cause HRU: MDSI versus non-MDSI cohorts. (a) During the 1-month post-period. (b) During the 6-month post-period. Abbreviations: HRU, health care resource utilization; MDSI, major depressive disorder and acute suicidal ideation or behavior; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; ED, emergency department.

The majority of patients with MDSI and an index event classified as either an inpatient encounter or ED visit (n = 64,005) were discharged to home or self-care (65.4%). Other discharge dispositions included discharge to a psychiatric hospital (17.8%) and other types of facilities (11.7%). The disposition was unknown for 3.7% of patients, and 1.3% of patients left against medical advice.

Discussion

This was a real-world study analyzing the continuum of care of patients experiencing major depression and suicidal ideation and behavior. There have been limited studies within this patient population to date. This study used nationally representative data from an EHR database to gain insight into how patients with MDSI are managed in real-world clinical practice, with practical findings to help inform optimization of treatment pathways for this vulnerable population. Findings demonstrate that a substantial proportion of patients did not receive standard-of-care therapies to treat their underlying depressive disorder, including oral antidepressants and psychotherapy. The majority of patients with MDSI (∼90%) required hospitalization (i.e. inpatient stay, observation unit stay, or ED visit), which clearly highlights the fragility of this patient population. Furthermore, among the subset of the population with PHQ-9 scores available, the presence of possible ineffective treatment options, treatment inertia, treatment-resistant depression, and medication nonadherence were suggested by the observation that patients’ depression category often stayed the same or worsened after the suicide-related event. Despite the recognition of high rates of recurrence of suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and hospitalization in patients with MDD in the 6 months following a suicide-related eventCitation12, a sizeable proportion did not have an all-cause or MDD-related outpatient visit 1 month and 6 months after the index event. In totality with the aforementioned findings, it was consistent to observe high levels of HRU among patients with MDSI as well as significantly higher odds of an all-cause hospital encounter compared to patients without MDSI in the periods after the suicide-related event.

These results expand upon previous findings from a cross-European study of data from the National Health and Wellness Survey, which showed that, among patients with MDD, those with suicidal ideation were at greater risk of HRU events compared with those with MDD but without suicidal ideation (relative risk: health care provider visits, 7.84; general/family practitioner visits, 3.88; hospitalizations, 2.48; ER visits, 2.38)Citation25. The study also showed that HRU was generally higher among patients with MDD, regardless of suicidal ideation, compared with the general populationCitation25.

Despite significant contact with health care practitioners among patients with MDSI observed in the dataset, sizeable proportions did not receive any antidepressant therapy or psychotherapy, even after a documented suicidal ideation or suicide attempt. This is consistent with previous studies that reported inadequate treatment for patients with MDD or suicidal ideation. In an analysis of data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, more than 30% of participants who made suicide plans and/or attempted suicide received no mental health treatment either before or after planning or attempting suicideCitation26. Patients with mental health conditions may face numerous barriers to receiving care. A recently published study evaluated patients with suicidal ideation and found certain factors, such as stigma, anticipation of provider overreaction, and loss of autonomy, precluded patients from disclosing their suicidal ideations to health care providersCitation27.

The PHQ-9 is recognized as an important quality measure by NCQACitation18; however, its use in routine clinical practice varies. EHR studies report the PHQ-9 form was used to evaluate 13.5–73.7% of patients with depression in primary careCitation28–31. Other studies have reported incomplete PHQ-9 questionnaires in an analysis of depression in EHR recordsCitation32. In the current study, only a small proportion of patients had PHQ-9 scores recorded in their medical records (<10%), and among the subgroup of patients with PHQ-9 scores during both the pre-period and 6-month post-period, results suggest a need for further investigation of the reasons for symptom improvement (and lack thereof). For example, clinical inertia, a well-recognized phenomenon in the treatment of depression, has been explored in previous studies, although not in the MDSI subpopulation specifically. Research using data from the Quality Improvement for Depression collaboration found that only 29% of patients receiving care for depression achieved a full response to therapy (defined as >50% improvement in symptoms), while treatment adjustments were made for 64% of patientsCitation33. Another study assessed clinician adherence to depression practice guidelines and found low adherence to nearly half the recommendations (e.g. assessment of symptoms and history of depression, management of suicide risk, and treatment adjustment for patients who do not respond to initial treatment)Citation34.

Inadequate treatment of mental health disorders has led to evaluation of varying strategies, such as enhanced mental health resources and collaborative care models, to improve the quality of careCitation35,Citation36. Currently, there are no standard-of-care clinical practice guidelines for MDSI. Related guidelines include the 2019 Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense (VA/DoD) Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Patients at Risk for SuicideCitation37, the 2019 American Psychiatric Association (APA) Clinical Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Depression Across Three Age CohortsCitation38, and the 2019 National Action Alliance (NAA) Best Practices in Care Transitions for Individuals with Suicide RiskCitation39. For individuals with a history of suicide risk who are transitioning from suicide-related hospitalization to outpatient care, these guidelines recommend a team-based approach, such as scheduling a follow-up appointment within 24 hours of discharge and no later than 7 days post-dischargeCitation39. In this study, substantial proportions of patients did not receive any follow-up care or symptom screening within 30 days. The PHQ-9 presents an opportunity for IDNs to improve treatment for patients with MDSI by collection of relevant depression data. Given its inclusion in multiple quality measures, including HEDIS, the PHQ-9 is a practical way to screen for and assess depression symptom severity in the real worldCitation40. Additionally, the PHQ-9 was referenced in guidelines or endorsed by multiple health systems as a tool to screen for and manage depressionCitation41–43, making it even more relevant to clinicians and further supporting its use in the management of depression. Identification of individuals at risk for MDD and with suicidal ideation or behaviors provides a chance to improve the treatment and management of their depression. Routine use of the PHQ-9 presents an opportunity to identify these patients more effectively in a real-world setting.

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting results of this study. First, the study was unable to account for assessments that might have been made outside of the clinics/hospitals that contribute data to the Optum EHR database. In an effort to address this issue, the analysis focused on only patients who were enrolled in an IDN; however, this action may limit the generalizability of these findings to patients from other health care settings. Additionally, within any EHR database, data can be inaccurate or incomplete, or patients can drop out of the dataset. Second, prescription data reflect the prescriptions written by the health care provider and thus do not necessarily indicate the medication was filled and taken as prescribed; alternatively, patients may have received medication outside of the IDN. Third, this study used propensity score matching to adjust for confounding; however, the possibility of unmeasured or residual confounding cannot be excluded. Fourth, because no scheduling data were reported in this dataset, the number of patients who met the follow-up appointment was not available. Fifth, the proportion of outpatient visits for the MDSI population in this study was relatively small; visits were likely under-recorded due to stigma or the perception of accidental injuryCitation27,Citation44–46. In addition, the entire population-based distribution could be underestimated, based on suicidal ideation and suicide attempt codes, if the intent or cause of an injury was unknown. Finally, PHQ-9 scores were available for a relatively small subset of the population with MDSI. The analysis of changes in depression severity and post-event treatments were therefore limited in this study. Additionally, it is possible that there is systematic bias in why some patients might receive a PHQ-9 assessment compared to others. Thus, it cannot be inferred that the findings are generalizable to the entire population in this sample or externally. Expanding the study population of patients with MDSI may be considered in future studies.

Conclusions

This study documents a high level of HRU among patients with MDSI as well as higher odds of an all-cause hospital encounter relative to patients without MDSI, with the greatest number of health care encounters occurring in the outpatient setting. Few patients had PHQ-9 scores recorded, and sizeable portions of patients did not receive pharmacologic and/or nonpharmacologic therapy, even after a documented suicidal ideation or suicide attempt. To our knowledge, this is the first study focused on the MDSI population receiving care in the IDN setting. This study illustrates the urgency for health systems to dedicate greater resources to studying treatment patterns and outcomes for patients with MDSI. Results of this study suggest there is an urgent need for improved screening, data collection, treatment, and follow-up within health care systems for this vulnerable population.

Transparency

Competing interests

CN, YC, MS, and JV are employees of Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, and are stockholders in Johnson & Johnson. MS is an employee of Mu Sigma, which received consultancy fees from Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, for performing the study.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study design and concept, data analysis and review, data interpretation, and manuscript review.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Previous presentation

Neslusan C, et al. Poster presented at: Neuroscience Education Institute (NEI) MAX! Virtual Congress; 5–8 November 2020.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (21.2 KB)Acknowledgements

Medical writing support was provided by Caryn Gordon, PharmD, and Courtney St. Amour, PhD, of Lumanity Communications Inc., and was funded by Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC.

Data sharing statement

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Additional information

Funding

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Major depressive disorder. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. p. 160–168.

- National Institute of Mental Health. Depression; 2020 [updated Feb 2018; 2020 Oct 22]. Available from: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/depression/index.shtml.

- GBD Disease Injury Incidence Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392(10159):1789–1858.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: results from the 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS publication no. PEP20-07-01-001, NSDUH series H-55). Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2020.

- Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, et al. Suicide and suicidal behavior. Epidemiol Rev. 2008;30(1):133–154.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. (HHS publication no. PEP19-5068, NSDUH series H-54). Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2019.

- Greenberg PE, Fournier AA, Sisitsky T, et al. The economic burden of adults with major depressive disorder in the United States (2010 and 2018). Pharmacoeconomics. 2021;39(6):653–665.

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Crossing the Quality Chasm: Adaptation to Mental Health and Addictive Disorders. Improving the quality of health care for mental and substance-use conditions: quality chasm series. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US); 2006.

- Clarke JL, Skoufalos A, Medalia A, et al. Improving health outcomes for patients with depression: a population health imperative. report on an expert panel meeting. Popul Health Manag. 2016;19(suppl 2):S1–S12.

- Neslusan C, Chopra I, Joshi K, et al. Clinical and economic burden of major depressive disorder with acute suicidal ideation or behavior in a US Veterans Health Affairs database. Curr Med Res Opin. 2022;38(9):1603–1611.

- Pilon D, Neslusan C, Zhdanava M, et al. Economic burden of commercially insured patients with major depressive disorder and acute suicidal ideation or behavior in the United States. J Clin Psychiatry. 2022;83(3):21m14090.

- Neslusan C, Voelker J, Lingohr-Smith M, et al. Characteristics of hospital encounters and associated economic burden of patients with major depressive disorder and acute suicidal ideation or behavior. Hosp Pract (1995). 2021;49(3):176–183.

- Borentain S, Nash AI, Dayal R, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in major depressive disorder with suicidal ideation: a real-world data analysis using PatientsLikeMe platform. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):384.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Utilization of the PHQ-9 to monitor depression symptoms for adolescents and adults; 2019 [cited 2022 Nov 17]. Available from: https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/pqmp/measures/chronic/chipra-245-fullreport.pdf.

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613.

- Santos IS, Tavares BF, Munhoz TN, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) among adults from the general population. Cad Saúde Pública. 2013;29(8):1533–1543.

- Levis B, Benedetti A, Thombs BD; DEPRESsion Screening Data (DEPRESSD) Collaboration. Accuracy of Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for screening to detect major depression: individual participant data meta-analysis. BMJ. 2019;365:l1476.

- NCQA. HEDIS depression measures specified for electronic clinical data systems [cited 2021 Jan 26]. Available from: https://www.ncqa.org/hedis/the-future-of-hedis/hedis-depression-measures-specified-for-electronic-clinical-data/.

- Hedegaard H, Schoenbaum M, Claassen C, et al. Issues in developing a surveillance case definition for nonfatal suicide attempt and intentional self-harm using International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) coded data. Natl Health Stat Report. 2018;(108):1–19.

- Lin J, Szukis H, Sheehan JJ, et al. Economic burden of treatment‐resistant depression among patients hospitalized for major depressive disorder in the United States. Psychiatr Res Clin Pract. 2019;1(2):68–76.

- Zhdanava M, Voelker J, Pilon D, et al. Excess healthcare resource utilization and healthcare costs among privately and publicly insured patients with major depressive disorder and acute suicidal ideation or behavior in the United States. J Affect Disord. 2022;311:303–310.

- Sussman M, O'Sullivan AK, Shah A, et al. Economic burden of treatment-resistant depression on the U.S. health care system. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2019;25(7):823–835.

- Austin PC. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivariate Behav Res. 2011;46(3):399–424.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

- Jaffe DH, Rive B, Denee TR. The burden of suicidal ideation across Europe: a cross-sectional survey in five countries. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019;15:2257–2271.

- Choi NG, DiNitto DM, Marti CN. Mental health treatment use and perceived treatment need among suicide planners and attempters in the United States: between and within group differences. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8:305.

- Richards JE, Whiteside U, Ludman EJ, et al. Understanding why patients may not report suicidal ideation at a health care visit prior to a suicide attempt: a qualitative study. Psychiatr Serv. 2019;70(1):40–45.

- Elliott T, Renier C, Palcher J. PS1-29: PHQ-9 use in clinical practice: electronic health record data at Essentia Health. Clin Med Res. 2013;11(3):167–168.

- Gill JM, Chen YX, Grimes A, et al. Electronic clinical decision support for management of depression in primary care: a prospective cohort study. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2012;14(1):PCC.11m01191.

- Adekkanattu P, Sholle ET, DeFerio J, et al. Ascertaining depression severity by extracting Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) scores from clinical notes. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2018;2018:147–156.

- Korsen N, Gerrish S. Use of PHQ-9 for monitoring patients with depression in integrated primary care practices. Ann Fam Med. 2022;20(suppl 1):2769.

- Coley RY, Boggs JM, Beck A, et al. Defining success in measurement-based care for depression: a comparison of common metrics. Psychiatr Serv. 2020;71(4):312–318.

- Henke RM, Zaslavsky AM, McGuire TG, et al. Clinical inertia in depression treatment. Med Care. 2009;47(9):959–967.

- Hepner KA, Rowe M, Rost K, et al. The effect of adherence to practice guidelines on depression outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(5):320–329.

- Patel V, Belkin GS, Chockalingam A, et al. Grand challenges: integrating mental health services into priority health care platforms. PLoS Med. 2013;10(5):e1001448.

- Asarnow JR, Jaycox LH, Duan N, et al. Effectiveness of a quality improvement intervention for adolescent depression in primary care clinics: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293(3):311–319.

- Department of Veterans Affairs, Department of Defense. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the assessment of management of patients at risk for suicide; 2019 [cited 2022 Jun 22]. Available from: https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/srb/VADoDSuicideRiskCPGProviderSummaryFinal5088212019.pdf.

- American Psychological Association. APA clinical practice guideline for the treatment of depression across three age cohorts; 2019 [cited 2022 Jun 22]. Available from: https://www.apa.org/depression-guideline/guideline.pdf.

- National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention. Best practices in care transitions for individuals with suicide risk: inpatient care to outpatient care. Washington, DC: Education Development Center, Inc.; 2019.

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. The PHQ-9: a new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatr Ann. 2002;32(9):1–7.

- Kaiser Permanente. Adult & adolescent depression screening, diagnosis, and treatment guideline; 2017 [cited 2022 Nov 17]. Available from: https://wa.kaiserpermanente.org/static/pdf/public/guidelines/depression.pdf.

- The Management of Major Depressive Disorder Working Group. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the management of major depressive disorder; 2016 [cited 2022 Nov 17]. Available from: https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/mdd/VADoDMDDCPGFinal508.pdf.

- Department of Veterans Affairs, Department of Defense. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the management of major depressive disorder; 2022 [cited 2022 Jun 22]. Available from: https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/mdd/VADoDMDDCPGFinal508.pdf.

- Voelker J, Cai Q, Daly E, et al. Mental health care resource utilization and barriers to receiving mental health services among US adults with a major depressive episode and suicidal ideation or behavior with intent. J Clin Psychiatry. 2021;82(6):20m13842.

- Knaak S, Mantler E, Szeto A. Mental illness-related stigma in healthcare: barriers to access and care and evidence-based solutions. Healthc Manage Forum. 2017;30(2):111–116.

- Jordan JT, McNiel DE. Perceived coercion during admission into psychiatric hospitalization increases risk of suicide attempts after discharge. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2020;50(1):180–188.