Abstract

Aim

The goal of this research was to quantify and qualify all the costs associated with multiple myeloma (MM) from a healthcare and societal perspective and to highlight certain costs that are often underestimated.

Materials and Methods

The study used a mixed methods approach that consisted of three phases: a systemic literature review (SLR), a virtual roundtable discussion based on the results of the SLR, and an online survey.

Results

In total, 4321 records were identified by literature and snowball searches. After applying the eligibility criteria, 49 articles were included in the narrative summary. As combination treatments have become the mainstay of MM treatment, drug costs have become the most important component of the total healthcare costs. Collected evidence suggests that optimizing treatment pathways, besides prolonging patient survival and maintaining quality of life, has the potential to generate cost savings for all stakeholders (payers and patients). Improved patient access to new therapies that can improve outcomes may reduce the “financial toxicity” of MM by decreasing patients’ and caregivers’ productivity loss due to better prognosis and it also has the potential of reducing patients’ direct health care payments.

Limitations

Heterogeneity of research objectives of included studies, costing methods, and applied measurement units limited the comparability of cost data between studies. Data for more than half of the world’s population, including China, Russia, the Middle East, and Africa were not investigated.

Conclusion

While treatment costs are burdensome for healthcare systems, it is only one of several items that make up the True Cost of MM. Understanding these burdens is one way to argue for optimized treatment pathways and improve patient outcomes by tearing down access barriers.

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a malignant plasma cell disease with 159,985 new cases being diagnosed annuallyCitation1 worldwide. The true costs of the disease are rising for two main reasons. First, disease incidence has increased globally by 126% in the last 25 yearsCitation2 due to increasing awareness, access to better diagnostics and aging populations. Second, patient survival has improved due to the increased efficacy of novel therapies and drug combinations. Both factors lead to the increasing costs of MM treatment with considerable impacts on healthcare budgets.

Despite the research and data collection in the field of MM, there still is a lack of an all-encompassing report that reflects the true and complete cost of the disease. We can assume that the overall disease cost of MM is often underestimated as traditional analyses focus solely on direct treatment costs on the healthcare system such as diagnosis, in- and out-patient care and/or drug prescription costs. However, the patient pathway involves more than just routine medical diagnosis, inpatient care and/or drug prescriptions. When confronted by MM, patients seek professional help and advice from their doctors, and also rely on support from family members, peers and fellow patients.

In cost-of-illness (COI) studies, the estimation of direct medical costs is relatively uncontroversial, and utilization and cost of necessary treatments, diagnostics and other services of health care providers are historically captured in such studiesCitation3. On the other hand, there are more difficulties related to the estimation of costs outside the health care system, including the supportive care service costs of the disease (such as caregiving) and indirect costs (such as loss of income); which, if included, might confirm that direct treatment costs are only a fraction of the true economic burden of managing patients with MM.

Rationale and research objectives

The overall costs of MM are often underestimated as studies and assessments focus strongly on direct medical costs. Therefore, the goal of this research initiative was to quantify and qualify all the costs associated with the disease from a healthcare and societal perspective and to highlight certain costs that are often underestimated. An analysis of the true costs of MM could be used to estimate the burden on patients and raise awareness on the need to further increase patient access to the best possible treatment and, thereby, increase patient survival and quality of life.

The Beyond Medicines’ Barriers (BMB) Consortium was officially launched in January 2020 with the intention of helping MM patients worldwide gain greater access to much needed medicines. It is a consortium of medical and scientific research professionals, health economists, health technology assessment (HTA) experts, patients and their caregivers who are working together to fulfil the aims of the BMB initiative. The research goals and objectives align with the WHO UHC 2030Citation4, UN Agenda 2030Citation5, European Medicines Agency (EMA 2025 Strategy)Citation6 and EUnetHTA (European network for Health Technology Assessment)Citation7. Our intent is to not duplicate efforts but rather to compliment the work of the international community, and to ensure transferability and generalisability for knowledge sharing to other therapeutic areas.

Methods

The research study used a mixed methods approach that consisted of three phases. The first phase was the systemic literature review (SLR). Phase 2 involved a virtual roundtable discussion based on the results of the SLR and Phase 3 consisted of an online survey.

Phase 1: Systemic literature search strategy

The systemic literature search strategy was based on a combination of search strings (Supplementary Tables 1–4), allowing the capture of all relevant keywords and synonyms that may have appeared in the available literature. The literature search was performed on several databases, which included:

Medline (via PubMed)

Scopus

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews

PROSPERO

CRD Database

CEA Registry

Grey literature

Websites of HTA Agencies (i.e. NICE, CADTH)

Published conference abstracts of the American Society of Clinical Oncology and American Society of Hematology annual meetings

Due to the overlap of coverage between these databases, search results were first de-duplicated then screened by title/abstract and full-text for exclusion of irrelevant studies. All identified records and eligible studies underwent double screening; two independent reviewers went through the same set of articles and the potential conflicts were resolved by a third reviewer.

SLR key eligibility criteria and article selection

Articles were included if they were published on or after January 2010 and contained cost or resource use data originating from 2010 onward. The rationale behind the chosen cut-off is the rapidly changing therapeutic landscape in MM and cost escalation of novel anticancer medicationsCitation8,Citation9. Studies were considered if the patients were 18 years of age or older and diagnosed as having SMM (Smoldering MM) or MM. Articles were included if (1) the research was conducted in France, Germany, Italy, Spain, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, Colombia, Argentina and Austria, and (2) study language was English, French, German, Italian or Spanish. Worldwide level studies were also eligible. The geographical restriction was applied to align the scope of systematic review and roundtable discussion. Study types included COI and burden of disease studies, economic evaluations, systematic reviews, randomized controlled trials and studies published as abstracts or conference presentations (only if enough details were presented that allowed for evaluation of the methodology and the assessment of results). The reason for searching and reviewing previous systematic reviews was two-fold:

investigate if any other similar systematic review was performed in the recent period (not to duplicate any research), and

if a similar review was published earlier, further relevant primary studies within the citations of the existing systematic reviews could be identified.

Excluded articles were those: (1) without relevant title and English abstract, (2) without human subjects within the scope of this study, (3) without relevant outcome data, (4) without a relevant country within the scope of the study, (5) with less than 10 myeloma or smouldering myeloma patients. Case studies and editorials, as well as reviews and opinion papers were also excluded.

Data extraction and analysis

Data were recorded in a standard Microsoft® Office Excel spreadsheet and the extracted data was double-checked by a second reviewer. The following data items were collected:

General information on the paper (first author, publication year, country, study objective, main conclusion, study limitations)

Study dimensions (study design, data source, study period)

Baseline characteristics of studied cases (age, gender, disease stage, subgroups with available data)

Study perspective (healthcare, non-healthcare, third party payer or patient)

Costing method

Cost and resource-use estimates (costing year, follow-up period, unit, dispersion, currency)

The methodological quality of the included papers was assessed to determine the robustness of the review findings. It was evaluated using the method explained by Larg et al.Citation10 for COI studies and the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) ChecklistCitation11 for economic evaluations. In full-text articles, level of risk of bias was defined according to the share of positive answers to checklist questions. If the share of fulfilled questions was below 50%, between 50% and 70%, or above 70%, the study was deemed as being associated with high, moderate or low risk, respectively. The review was conducted and reported in compliance with the PRISMA StatementCitation12. Ethics approval was not required.

A narrative synthesis of research findings was provided, quantitative analysis was not performed. During the narrative synthesis special focus was dedicated to identifying existing evidence gaps in the scientific literature. These could be highlighted directly by the authors of identified studies or could be identified by the authors of the current systematic literature review.

Phase 2: virtual roundtable

The 1-hour virtual roundtable occurred on June 8, 2020 and included 49 participants from civil society: patients and caregivers, as well as HTA and medical experts in the field of MM. Slides were developed based on the results of the SLR and presented during the virtual roundtable. The suggestions and comments of the roundtable participants were recorded and used to develop phase 3 of the study.

Phase 3: online survey

Questions included in the online survey were shaped by the results of the virtual roundtable meeting and took the form of open-ended questions in English. A thematic analysis of responses was performed alongside the topics identified and discussed during the roundtable meeting in Phase 2. The responses were analysed by a single researcher and interpretation was backchecked by a second researcher. There were two different surveys administered: one for patients and caregivers, a second for health care professionals (HCPs) and HTAs. The survey was sent out by email to patients, HCPs and HTAs on July 13, 2020 using the International Myeloma Foundation’s mailing list and was electronically self-administered. The survey included 9 participants in total from the following countries: one each from Germany, France, the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, Columbia, Argentina and 2 from Hungary. The list of the questions is found in . Data collected in this study remained anonymous and confidential.

Table 1. Complete list of questions administered in the online survey.

Results

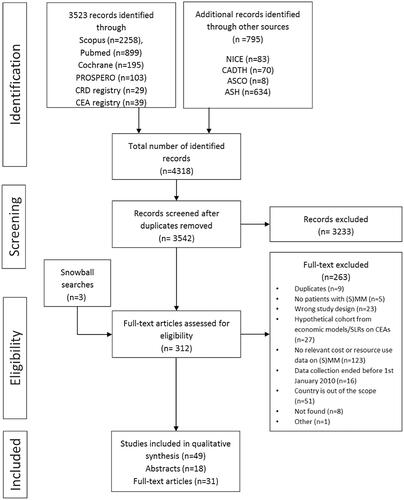

A total of 4321 records were identified by the literature and snowball searches. Records were imported into a reference management software, where reviewers conducted the title and abstract screening based on predefined criteria. Three hundred and nine (309) articles passed the initial screening process and were included in full-text screening. Snowball searches resulted in 3 additional studies included for full-text screening. After applying the eligibility criteria, 31 full-text studies, 14 original research abstracts and 4 systematic review abstracts were included in the data extraction, giving a solid basis for the narrative summary (). In case of four conference abstracts of previous systematic reviews, full presentations or posters were not available. We decided not to lose the main conclusions based on those abstracts; therefore, these studies were included.

Quality assessment of included full-text papers indicated a moderate or low risk of bias in the majority of the studies. However, the applied instruments warranted high risk of bias in seven cases. Results of the quality assessment have been marked in Supplementary Table 5.

Studies with multinational sample sizes (n = 10) and focusing on the United Kingdom (n = 12) were in majority across the identified articles.

Distribution by topic shows the general predominance of implications of chosen treatment regimens (addressed in 16 studies), while impact of disease stage and optimized treatment pathways (i.e. early discharge/outpatient/home care models) were both investigated in seven articles. Disease symptoms and complications were the focus in 5 studies. Autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) and the impact of planned/unplanned admissions were the main topics in 3 and 2 studies, respectively.

For a detailed description of the included studies, see the Supplementary Table 5.

Lower costs when patients achieve treatment response to therapy

Although treatment costs were the largest component of overall disease cost, several studies showed evidence of lower overall costs when patients achieved good therapy responseCitation13–17. Studies were consistent in ranking combination treatment cost as being the largest component of overall disease cost (). Gonzalez-McQuire et al.Citation14 assessed the real-world healthcare resource utilization (HRU) and costs associated with different treatment regimen used in relapsed MM in the United Kingdom, France, and Italy (analysis of 1,282 patients) in 2015. Costs were highly variable between countries. The mean total healthcare costs associated with a single line of treatment were €51,717 (SD: 42,342) in the United Kingdom, €37,009 (SD: 31,530) for France, and €34,496 (SD: 40,305) for Italy. Costs were largely driven by anti-myeloma medications contributing to 95.0% (United Kingdom), 90.0% (France) and 94.2% (Italy) of total costs. The total mean costs in the investigated countries were consistently higher for lenalidomide (range: €42,584–70,260) and pomalidomide based regimens (range: €64,468–78,595) across the 2 L–5L treatment lines and were lower for bendamustine-based regimens (range: €8,454–18,846). Mean cost per month across the countries from start of treatment until progression was lower for patients achieving a very good partial response or better (VGPR+) (range of €2,798–4,661) when compared to those with partial response (range of €2,920–6,427) and those with stable or progressive disease (range of €2,815–6,513). However, in patients achieving VGPR+, the total mean costs from treatment initiation to progression were higher because of the longer treatment duration (from start of treatment until progression) (range of country-specific total mean costs in those with very good partial response or better: €51,412–59,107 versus patients with partial response: €33,320–53,065 versus patients with stable or progressive disease: €18,874–36,405).

Table 2. Proportion of drug costs in total costs.

The study performed by Ashcroft et al.Citation13 suggests that maintenance therapy after first line can delay progression to further lines of therapy and reduce resource use on a time horizon of 15 months. displays the country-specific cost aspects of maintenance therapy post-transplant (analysis of 91 patients with complete resource use data). Applying country specific unit costs from the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Italy and Spain indicated different cost-saving potential related to maintenance therapy (total cost per month was €438.81 – €1001,74 in non-maintenance patients versus €238.29 – €638.14 in maintenance patients). Expenditure on hospitalization, HCP visits and monitoring tests was higher for patients without maintenance therapy (hospitalizations: €243.12 versus €59.78; HCP visits: €498.58 versus €181.11; monitoring tests: €198.48 versus €84.20 per patient/month, respectively).

Table 3. Cost aspects of being on maintenance therapy post-transplant.

Optimizing patient pathway may reduce healthcare costs and improve patient survival and quality of life

Optimizing MM treatment pathways may translate, most importantly, into increased patient survival and quality of life but also into decreased societal burden. Several studies addressed the question of how to optimize the treatment pathway to expand from traditional inpatient care to outpatient or even home-based strategies when possible. It was concluded that these approaches have the potential to generate cost savings for the healthcare system and at the same time improve the patient experience by allowing more time to be spent with the familyCitation18–24. As an example, Holbro et al.Citation18 investigated the cost-effectiveness of outpatient autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) in MM patients compared to usual inpatient setting. Authors found that the total cost of care was 62,259 CAD and 42,737 CAD in inpatient and outpatient ASCT, respectively. The cost of hospitalization related to the transplantation accounted for 41.9% of total costs in case of the inpatient setting, while the costs directly related to the outpatient ASCT procedure accounted only for the 6.1% of total costs, which is substantially lower.

Economic burden of MM is higher than other cancers

In the study by Kolovos et al.Citation25 the average number of MM-related hospital admissions per patient was more than three times higher than that of colon cancer (4.5 vs 1.4, respectively [statistical significance not tested]), thus leading to a higher economic burden per patient for those being admitted to hospital with MM (£2,455 for MM vs. £1,876 for colon cancer [statistical significance not tested]). Unplanned hospital admissions only represented 10% of all admissions, but accounted for 55% of the total hospitalization costsCitation25. In the same study, the average cost per patient per year reported for MM-related admissions was nearly three times higher than that of the average patient in the National Health Service (£2,455 vs £870 [statistical significance not tested])Citation25. When analysing high- and low- cost cancer patients in Ontario, Canada (study by De Oliveira et al. Citation26), a statistically significant overrepresentation of MM was found in the high cost group (share of MM patients was 1.6% and 0.3% in the high and non-high cost groups, respectively [total patient sample: n = 557,192] (p < .001)). Similar comparative analysis on different cancer types including the sub-group of myeloma patients was not identified from other eligible countries.

High patient and caregiver burdens are associated with important productivity loss

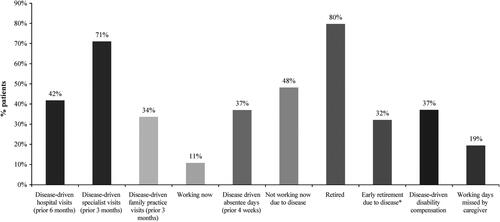

According to the study by Robinson et al.Citation17, pooling data on 263 refractory patients, being unable to work due to MM and disease-driven early retirement were moderately associated with age, both impacting more the younger patients (results of Spearmen correlation analysis were −0.67 and −0.66, respectively. Both parameters achieved statistical significance at p < .01). Time lost due to healthcare services, treatments and general absenteeism was an obvious opportunity cost for both patients and caregivers. The socio-economic burden of relapsed/refractory MM was also found to be important when patients and caregivers were asked about their specialist visits, hospital visits, reduced/absent working hours, and potential early retirement in the study by Robinson et al.Citation27 (). Only 10.8% of surveyed myeloma patients ≤ 65 years of age were working, among whom 37.0% reported disease-driven absenteeism ≥ 1 day over the previous 4 weeks. Almost half of the patients (48.2%) who did not work indicated that it was due to their health statusCitation25.

Figure 2. Leading Burdens on Patients with MM and their Caregivers. Adapted from Robinson et al.Citation27

Jackson et al.Citation16 determined that productivity loss following autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT), calculated with the human capital approach (average per-patient productivity loss discounted over a 20-year time horizon), was €290,601 on average (Range: €240,000 [Spain] - €308,000 [Germany]). The short-term productivity loss calculated using the friction cost approach (calculating with missed working hours until replacing the MM patient) was €2,575, which is still important compared to treatment costs.

Virtual roundtable and online survey results

Recurrent themes that were raised during the virtual roundtable discussions and online survey results were:

There is limited data available with regard to low- and middle-income countries and environments.

“Fragmented” health care systems (including multiple public and private payers), seemingly lead to a higher complexity of treatment pathways, which most likely increases overall burden and financial toxicity for patients. This is poorly documented in current publications.

Transparent access barriers (e.g. innovative medicines not being reimbursed or only available with significant copayment) and hidden access barriers (e.g. volume limits, limited diagnostic capacities) are both important factors but not well evaluated to date.

Limited access to innovative drugs remains one of the main barriers for patients to achieve a better outcome.

The cost of delayed diagnosis and cost of progression, relapse and death vs the cost of prolonging a progression free-state and overall survival.

Missing other costs (i.e. cost of transportation).

Future research on the true costs of MM will benefit from more patient representation.

Discussions

Our research showed that several cost elements contribute to the overall cost of MM. These need to be considered when one estimates the true cost of the disease. Besides the healthcare system, there are many other actors who face significant economic burden due to MM. The government and the society pay for early retirement and disability allowances, while the employer must accept missed working hours and reduced productivity of the patient and caregivers. Latter actors spend much of their time providing care and support, which is then expressed in opportunity cost. Finally and most importantly, the patient - besides facing emotional stress and reduced quality of life – also has to deal with time loss and reduced activity, which then manifest in potential job and income losses.

It is critically important that patients and prescribers have access to a wide variety of treatment options in order to optimize the treatment pathway and improve outcomes for the patient. The most important factor for improved patient survival is the actual access to the appropriate treatment options. In the short run, this has the potential to reduce the direct healthcare payments by patients and prevent further productivity loss, leading to relative cost savings both for the patient and society.

Substantial improvements in survival in the past decade can be attributed in part to the availability of novel therapies. Tearing down access barriers will lead to better treatment outcomes and better quality of life for patients but will also lead to higher direct treatment costsCitation28. Cost drivers include the use of combination therapies that have become a mainstay of MM treatment, and which are the most important component of the total healthcare costs. Better therapies and innovation come at a cost, which are important considerations of the true costs. This will have to be balanced not only with the additional health gains provided by the novel therapies (e.g. clinical benefits, QALY gains, etc.), but with the reduction in productivity loss and indirect costs to society. Important to note that the current research focused on the economic burden of MM with special attention to patient and caregiver burdens. This aspect did not consider the additional gains (e.g. clinical benefits, QALY gains, etc.) provided by the existing therapeutic options, and did not investigate if the incurred costs are acceptable compared to the benefits. To assess this, the existing cost-effectiveness studies should be reviewed and summarized. In the existing analyses it should be also investigated whether the identified elements of true cost were analyses or not. If not, an update of current value assessment approaches should be considered.

MM has a high COI compared to other types of cancer. The treatment paradigm has changed over the last decade to include better multidisciplinary care; nevertheless, the burden associated with treatment remains high and the total costs of care have increased overall.

In patients with relapsed MM achieving VGPR+, the total mean costs from treatment initiation to first progression were higher across treatment regimens because of the longer treatment duration (from start of treatment line until progression)Citation14. Effective drugs are able to delay disease progression resulting in reduced active treatment requirement needed and fewer unplanned hospitalizations; but, increase the total cost of treatment due to overall longer treatment duration. It is interesting to note that the mean monthly drug costs for patients treated with different treatment regimens were lower for individuals who achieved VGPR + than those who achieved partial response and those that had stable or progressive diseaseCitation14. Accordingly, improved treatment outcomes may reduce the overall HRU and related costs. Evidence suggests that finding the optimal treatment pathway for patients, including selecting the most appropriate treatment as well as the best structural model, has the potential to generate cost savings for all stakeholders (payers and patients), while improving the patient experienceCitation29. Different routes of drug administration can be a potential example of optimizing treatment pathways and selecting the most appropriate treatment for patients. In case of comparable effectiveness an oral or subcutaneous drug administration may carry substantial benefits over intravenous drug administration, which may allow for savings in both direct medical and indirect costs.

The burden of disease on patients, caregivers and society as a whole is significant. Even when patients are present at work, MM symptoms lead to disturbances in productivity. One way to lower the burden of disease is to consider an early discharge/home-care model. “The cost savings noted for outpatient ASCT represent significant savings for the Provincial Health Care System. These funds could be allocated, for example, to help cover the costs of new drugs to treat MM”Citation18. Reducing costs by optimizing and investing in other areas of healthcare delivery is a large focus for researchers.

Potential areas for savings (without compromising patient safety and satisfaction) include:

Enhancing the magnitude (depth and duration) of MM response to treatment, which can reduce the overall disease cost if the remission period can be prolonged resulting in a reduced requirement for active treatment.

Finding the optimal treatment pathway has the potential to generate cost savings for all stakeholders (payers and patients), while improving patient survival and quality of life.

Improving patient access to new therapies that can improve outcomes may diminish productivity loss in the workforce.

Future directions

There are still many gaps that need to be filled in with future research. Overall, a better understanding is needed of how patient access barriers can influence the financial toxicity for patients. Understanding how value assessment frameworks used by stakeholders (i.e. payers) can be adapted to accommodate new treatment paradigms (i.e. combinations, gene therapy, etc.) is an important area of interest. More information is needed on the burden of treatment; specifically, for newly diagnosed MM patients and those with Smoldering MM diagnosis (e.g. time spent with monitoring visits) versus the envisioned potential to induce longer responses with earlier treatment. Costs among specific subgroups of MM patients (e.g. frail elderly, renally impaired, high-risk patients defined cytogenetically or by expression analysis) also need to be studied.

In our review, regional disparities were not investigated; however according to worldwide-level studies, there are important differences to note. Despite an overall increase of autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplants rates, there are marked disparities when analysing regional distribution of usage. Inequality has been shown between high versus low- to middle-income countries with transplantation rates exceeding 20% in North America and Europe, while remaining underutilized in Africa and the East MediterraneanCitation30.

Understanding the financial toxicity of MM also includes future research into the impact of MM management on direct household expenditures and indirect costs associated with caregiver burden, as well as assessing the impact (in terms of caregiver burden) of using home care programs to reduce outpatient hospitalization visit costs for MM treatment (e.g. ASCT daily hospital visit costs).

Conclusions

While treatment cost is the most burdensome for healthcare systems, it is only one of several items that make up the true cost of MM. It is critically important that patients and prescribers have access to a wide variety of therapeutic options in order to optimize the treatment pathway and improve patient outcomes. As the most important factor for improved patient survival is actual access to appropriate treatment options, tearing down access barriers will lead to better treatment outcome and better quality of life for patients, but will also increase direct treatment costs. Furthermore, given the paucity of information related to indirect costs, ongoing research in this area is imperative. Improving access to healthcare will benefit MM patients but will only be possible if countries balance between the costs of delayed diagnosis and disease progression versus demonstration of the long-term benefits of new drug combinations. It will also require much more optimized patient management (e.g. out-patient treatment) and investments in novel patient management approaches, such as telehealth.

Limitations of the study include lack of country level comparisons due to differences in scope of the studies. Country specific differences could only be derived from multinational studies. Heterogeneity of study objectives, costing methods and applied measurement units limited the comparability of cost data between studies. Therefore, the focus of the analysis was on the elements of true and complete cost, key cost drivers in MM, presence of patient and caregiver perspective in the identified studies, and evidence gaps. A further limitation of the current research is that the number of participants in the online survey remained low. In spite of this, these results were utilized as the received responses were relevant from the patient burden point of view. It should be also noted that the current study was performed in a rapidly changing therapeutic era of MM treatments and only limited data were available on the novel therapeutics (e.g. immunotherapies) at the time of our literature search.

Progressively assessing the true cost of MM could complement clinical research initiatives aiming to define optimal treatment options, thereby, making these treatment options available to all patients.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

Funding for this study was provided by the International Myeloma Foundation and Sanofi US Services Inc.

Declaration of financial/other interests

MCQ and BD are employees of the International Myeloma Foundation. TZ and TA are employees of Syreon Research Institute, Budapest, Hungary. ZK and PK are partners at Syreon. Syreon received funding from the International Myeloma Foundation to collaborate with the BMB team for performing the SLR and conducting the analysis. The IMF received funding from Sanofi for leading, managing, performing the SLR, conducting the analysis and organising the Virtual Roundtable Meeting. MB, JLH and DH declare no conflict of interest.

Author contributions

MCQ, TZ, ZK and TA made substantial contributions to the conception and design of this study. Data acquisition and analysis was conducted by TA, TZ, and ZK. All authors contributed to the interpretation of data, took part in the drafting and revising of the manuscript, and gave final approval for the manuscript to be published. All authors agreed to be accountable for all aspects of this work.

Reviewer disclosures

The peer reviewers on this manuscript have received an honorarium from JME for their review work. A reviewer on this manuscript has disclosed that they have received research funding from Celgene, Janssen, Roche, Novartis, BMS, Amgen, Takeda, Pfizer, Incyte, Abbvie, GSK, Sanofi. They have in consultancy for Celgene, Janssen, Roche, Novartis, BMS, Amgen, Takeda, Pfizer, Incyte, Abbvie, GSK, Sanofi. The other peer reviewers on this manuscript have no other relevant financial relationships or otherwise to disclose.

Previous presentations

An abstract and poster presentation of the SLR data was presented during the virtual 2020 Lymphoma Leukemia & Myeloma Congress (October 21-24, 2020).

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (20.9 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (20.6 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (19.1 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (19 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (33.4 KB)Acknowledgements

Special thanks to the health care professionals, HTA experts, patients and caregivers who participated in the study. Editorial and medical writing assistance in the preparation of this manuscript was provided by Christina Sanguinetti. CS have provided permission to be acknowledged.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- International Myeloma Foundation. Who Gets Multiple Myeloma. 2019. [cited 2021 April 7]. https://www.myeloma.org/what-is-multiple-myeloma.

- Cowan AJ, Allen C, Barac A, et al. Global burden of multiple myeloma: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(9):1221–1227.

- Drummond M. Cost-of-Illness studies. Pharmacoeconomics. 1992;2(1):1–4.

- World Health Organization (WHO) Universal health coverage 2030 (UHC); 2022. https://www.uhc2030.org/

- United Nations (UN) Agenda 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2015. https://www.un.org/humansecurity/agenda-2030/

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). EMA Regulatory Science to 2025. EMA/110706/2020. 2020. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/regulatory-procedural-guideline/ema-regulatory-science-2025-strategic-reflection_en.pdf

- EUnetHTA (European network for Health Technology Assessment). 2021. https://eunethta.eu/

- Hamadeh I, Atrash S, Matusz Fisher A, et al. Advances & future prospects in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma patients. Adv Cell Gene Ther. 2021;4(1):e96.

- Hepp R. Blood cancer care costs skyrocket for Medicare patients. Oncology Times. 2020;42(S2):9–10.

- Larg A, Moss JR. Cost-of-illness studies: a guide to critical evaluation. Pharmacoeconomics. 2011;29(8):653–671.

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme 2018. CASP Economic Evaluation Checklist. [online]. https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/CASP-Economic-Evaluation-Checklist-2018_fillable_form.pdf.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, The PRISMA Group, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and MetaAnalyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

- Ashcroft J, Judge D, Dhanasiri S, et al. Chart review across EU5 in MM post-ASCT patients. Int J Hematol Oncol. 2018;7(1):IJH05.

- Gonzalez-McQuire S, Yong K, Leleu H, et al. Healthcare resource utilization among patients with relapsed multiple myeloma in the UK, France, and Italy. J Med Econ. 2018;21(5):450–467.

- Thompson JF, Teh Z, Chen Y, et al. A costing study of bortezomib shows equivalence of its real-world costs to conventional treatment. Br J Haematol. 2020;189(3):e76–e79.

- Jackson G, Galinsky J, Alderson DEC, et al. Productivity losses in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma following stem cell transplantation and the impact of maintenance therapy. Eur J Haematol. 2019;103(4):393–401.

- Robinson D, Jr Orlowski RZ, He J, et al. Economic burden of relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma: results from an international trial. Blood. 2015;126(23):875–875.

- Holbro A, Ahmad I, Cohen S, et al. Safety and cost-effectiveness of outpatient autologous stem cell transplantation in patients with multiple myeloma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19(4):547–551.

- Touati M, Lamarsalle L, Moreau S, et al. Cost savings of home bortezomib injection in patients with multiple myeloma treated by a combination care in outpatient hospital and hospital care at home. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(12):5007–5014.

- Martino M, Pellicano G, Moscato T, et al. At-home management of aplastic phase following high-dose melphalan and autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation for multiple myeloma patients: a pilot study. Blood. 2011;118(21):4497.

- Kodad SG, Sutherland H, Limvorapitak W, et al. Outpatient autologous stem cell transplants for multiple myeloma: Analysis of safety and outcomes in a tertiary care center. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2019;19(12):784–790.

- Lassalle A, Thomaré P, Fronteau C, et al. Home administration of bortezomib in multiple myeloma is cost-effective and is preferred by patients compared with hospital administration: results of a prospective single-center study. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(2):314–318.

- Nikonova A, Zeglinski C, Husain S, et al. Infectious complications in the outpatient and inpatient autologous stem cell transplantation setting for patients with multiple myeloma. Princess Margaret Cancer Center Experience. Blood. 2018;132(Suppl 1):4614–4614.

- Martino M, Console G, Russo L, et al. Autologous stem cell transplantation in patients with multiple myeloma: an activity-based costing analysis, comparing a total inpatient model versus an early discharge model. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2017;17(8):506–512.

- Kolovos S, Nador G, Kishore B, et al. Unplanned admissions for patients with myeloma in the UK: Low frequency but high costs. J Bone Oncol. 2019;17:100243.

- de Oliveira C, Cheng J, Chan K, et al. High-Cost patients and preventable spending: a Population-Based study. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2020;18(1):23–31.

- Robinson D, Jr Orlowski RZ, Stokes M, et al. Economic burden of relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma: Results from an international trial. Eur J Haematol. 2017;99(2):119–132.

- Wong R, Tay J. Economics of multiple myeloma. Blood. 2018;132(Suppl 1):4773–4773.

- Ashcroft J, Duran I, Hoefeler H, et al. Healthcare resource utilisation associated with skeletal‐related events in european patients with multiple myeloma: Results from a prospective, multinational, observational study. Eur J Haematol. 2018;100(5):479–487.

- Cowan AJ, Baldomero H, Atsuta Y, et al. The global state of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for multiple myeloma: an analysis of the worldwide network of blood and marrow transplantation (WBMT) database and the global burden of disease study. Blood. 2019;134(Supplement_1):412.