Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate the impact of early (at first-line) vs delayed (3-year delay) ofatumumab initiation and long-term clinical, societal, and economic outcomes of ofatumumab vs teriflunomide in relapsing multiple sclerosis (RMS) patients from a Spanish societal perspective.

Methods

A cost-consequence analysis was conducted using an Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS)-based Markov model. Inputs were sourced from ASCLEPIOS I and II trials and published literature.

Results

At the end of 10 years, compared with first-line teriflunomide treatment, early first-line ofatumumab initiation was projected to result in 35.6% fewer patients progressing to EDSS ≥ 7 and 27.8% fewer relapses. The ofatumumab cohort required 7.3% reduced informal care time and had 19% fewer disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) than the teriflunomide cohort. A 3-year delay in ofatumumab treatment (3-year teriflunomide + 7-year ofatumumab) was projected to result in 32.2% more patients progressing to EDSS ≥ 7, 20.2% more relapses, 5.4% increased informal care time, and 16.6% more DALYs compared with early ofatumumab initiation. Early ofatumumab initiation was associated with total annual cost savings (excluding disease-modifying-therapies’ acquisition costs) of €35,328 ($34,549; conversion factor 1€= $1.02255) and €24,373 ($23,836) per patient vs teriflunomide and 3-year delayed ofatumumab initiation, respectively.

Conclusions

This study highlights the benefits of early initiation of high-efficacy therapy such as ofatumumab vs its delayed initiation for improving the outcomes in RMS patients (having characteristics similar to those of patients included in the ASCLEPIOS trials). Ofatumumab treatment was projected to provide improved long-term clinical, societal, and economic outcomes vs teriflunomide treatment in RMS patients from a Spanish societal perspective.

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY

The therapeutic benefits of ofatumumab in relapsing multiple sclerosis (RMS) patients have been reported in the ASCLEPIOS I and II trials. Using an Expanded Disability Status Scale-based Markov model, this study aimed to assess the impact of early (i.e. at first-line, as the first treatment after diagnosis) vs delayed (i.e. 3-year delay) ofatumumab initiation in RMS patients from a Spanish societal perspective. In addition, the long-term clinical, societal, and economic outcomes of ofatumumab vs teriflunomide treatment were assessed. Evidence from this study suggests that early initiation of a high-efficacy therapy such as ofatumumab, compared with its delayed initiation, is an effective and cost-saving strategy for improving outcomes in RMS patients. Furthermore, patients receiving ofatumumab for 10 years are projected to experience comparatively better outcomes (clinical, societal, and economic) than those receiving teriflunomide.

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic neurodegenerative disorder characterized by inflammatory demyelination, gliosis, and neuronal loss. Estimates suggest that the prevalence of MS ranges between 0.10% and 0.13% of the total population in SpainCitation1,Citation2. MS is two times more prevalent in women than in men and is a leading cause of neurological disability in young and middle-aged adults, resulting in remarkable health and socioeconomic burdenCitation2,Citation3.

The economic burden imposed by MS in Spain is substantial. The overall annual costs related to MS in Spain are estimated to range from €1,200 to €1,337 million (amounting to €24,272 and €33,457 per patient per year)Citation3. Several moderate-efficacy (beta interferons, glatiramer acetate, dimethyl fumarate, and teriflunomide) and high-efficacy (natalizumab, alemtuzumab, cladribine, ocrelizumab, ofatumumab, fingolimod, and ozanimod) disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) are currently used in clinical practice for treating relapsing MS (RMS) patientsCitation4,Citation5. While escalation strategy is the most applied treatment algorithm for RMS patients, emerging data have shown a positive long-term impact of high-efficacy DMTs when initiated earlier in the disease course without compromising the safety of the patientsCitation5–9. There exists ambiguity across the MS treatment guidelines in terms of classifying DMTs based on their efficacyCitation10,Citation11. While the 2015 version of the Association of British Neurologists guidelines classifies S1P-receptor (S1P-R) modulators such as fingolimod as a moderate-efficacy DMTCitation10, the Brazilian guidelines categorizes fingolimod as a high-efficacy DMTCitation11. Given the differences between the MS treatment guidelines, we used evidence from recent studies, most of which report S1P-R modulators (i.e. fingolimod and ozanimod) as high-efficacy DMTsCitation4,Citation5,Citation9,Citation12–14.

Anti-CD20 B-cell-depleting therapies are high-efficacy DMTs that are increasingly being used to treat MSCitation15. Ofatumumab is the first fully human anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody approved for the treatment of RMS in EuropeCitation16. Data from pivotal clinical trials (ASCLEPIOS I and II) have demonstrated the therapeutic benefits and comparable safety profile of ofatumumab and teriflunomide in overall and treatment-naive RMS patientsCitation17,Citation18. Moreover, several studies have emphasized the therapeutic benefits of early initiation of high-efficacy therapy (HET) vs an escalation approach in MS patientsCitation5–9,Citation19–22. Although the clinical outcomes of HETs such as ofatumumab, in newly diagnosed treatment-naive MS patients has been reportedCitation17, the impact of early ofatumumab vs teriflunomide initiation on the long-term clinical, societal, and economic outcomes in RMS patients remains unexplored. To fill this knowledge gap, in the present study, a cost-consequence analysis was conducted to assess the impact of early (i.e. at first-line, as the first treatment after diagnosis) vs delayed (i.e. 3-year delay) ofatumumab initiation and the long-term clinical, societal, and economic outcomes of ofatumumab vs teriflunomide from a Spanish societal perspective. As part of the clinical outcomes, the present study assessed the distribution of MS patients in the different Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) states, the proportion of wheelchair and bedridden patients (i.e. EDSS ≥ 7), the number of relapses, and the number of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs). The economic outcomes assessed included direct (excluding DMT costs), relapse, and indirect costs. In addition, the societal outcomes assessed were productivity measure (i.e. % employed and % retired early) and informal care days per annum. A cost–consequence analysis is a simplified variant of economic evaluation in which the outcomes are reported separately from all costs (direct and indirect costs), allowing decision-makers to compare the incremental costs with the incremental consequences of the different interventionsCitation23.

Methods

Study population and interventions

The patient population considered in this model was aligned to patients included in the ASCLEPIOS I and II clinical trialsCitation18. Thus, the characteristics of the cohort at the start of the model were assumed to match the baseline characteristics of the ASCLEPIOS I and II trial participants (Supplemental Table S1)Citation18. The interventions considered for this study were ofatumumab 20 mg administered subcutaneously once every month and teriflunomide 14 mg administered orally once dailyCitation16,Citation24.

Model structure and inputs

A discrete-time Markov model based on the EDSS health states (0 = normal neurological exam and no disability; 10 = death) was developed in Microsoft Excel 2013. A hypothetical cohort of RMS patients with a cycle length of 1 year was tracked as they progressed through the disability states or naturally regressed to lower disability states or to the death state, as well as experienced a relapse (Supplementary Figure S1). The model was run from a societal perspective (i.e. direct [excluding DMT acquisition costs] and indirect MS management costs) and adopted a 10-year time horizon, as forecasting the productivity outcomes beyond 10 years using the current inputs might not be meaningful. The extrapolation of disability progression reported in the current study is in line with several published cost-effectiveness analysis and health technology assessment submissionsCitation25–28.

All model inputs and their respective sources are presented in Supplementary Table S2. For the natural history model, the most used sources of long-term natural history on disease progression in MS are the British ColumbiaCitation29 and the London Ontario datasetsCitation30. This British Columbia dataset measures changes in EDSS from 1980 to 1995 and was used instead of the London Ontario cohort, which may not reflect present-day MS patients as data were collected from the 1970s to the 1980s. The annualized relapse rate (ARR) by EDSS during the untreated course of the disease was based on published natural history dataCitation31,Citation32.

The transition probabilities for the on-treatment model (i.e. those receiving DMTs) were derived by applying the treatment efficacy (time to 6-month confirmed disability progression) observed during clinical trial to natural history disability progression. Disability progression efficacy was applied using hazard ratio (HR) for time to 6-month confirmed disability progression (CDP), and relapse efficacy was applied using the rate ratio (RR) for ARR. Based on evidence from the ASCLEPIOS trials, it is expected that patients on ofatumumab would take more time to progress to high disability states and achieve a lower relapse rate than those on other less efficacious DMTs. The inputs for the treatment-adjusted model, i.e. HR for time to 6-CDP and RR for ARR, were sourced from a network meta-analysis (NMA)Citation33. Efficacy estimates were considered from the NMA for ofatumumab vs teriflunomide because of its robustness over the effect estimate from the ASCLEPIOS trials. The annual discontinuation probabilities for ofatumumab and teriflunomide were sourced from the ASCLEPIOS trials and the above-mentioned NMACitation18,Citation33. The all-cause mortality rates for the general population were derived from the age- and gender-specific mortality rates for SpainCitation34 and adjusted for the MS population using the mortality multipliers reported in the literatureCitation35. MS-specific disability weights to calculate the DALYs were considered from Cho et al.’s studyCitation36. MS-related productivity loss data (i.e. proportion of patients employed or retired early and the number of informal care days per annum by EDSS) were retrieved from published literatureCitation37,Citation38. Retirement age and working days per year were assumed as 65 years and 251 days, respectively. Cost inputs, namely, annual disease-related costs stratified according to the EDSS state and adverse event (AE) costs (general clinical visit, neurology visit, and medication), were sourced from the Spanish Health Costs and Cost-Effectiveness Ratios databaseCitation39. Additionally, annual relapse costs were based on the severity of the relapse and adapted from Hawton et al.’s studyCitation40.

Model assumptions

Treatment effects were applied in the model in the form of delaying disability progression and reducing the number of relapses over the 10-year period to assess the clinical, societal, and economic outcomes of the treatment. Patients were assumed as fully adherent before treatment discontinuation. Patients who discontinued ofatumumab/teriflunomide treatment were moved to receive best supportive care either when they reached EDSS ≥ 7 or during all-cause discontinuation in line with the ASCLEPIOS trialsCitation18.

Scenarios

Three scenarios with a 10-year time horizon were simulated. The two base scenarios evaluated ofatumumab (i.e. 10 years on ofatumumab at first-line) vs teriflunomide (i.e. 10 years on teriflunomide at first-line). The third scenario simulated a 3-year delay in ofatumumab treatment (i.e. 3-year teriflunomide treatment, followed by 7-year ofatumumab treatment).

Model outcomes

Clinical outcomes, including the distribution of MS patients in the different EDSS states, the proportion of wheelchair and bedridden patients (EDSS ≥ 7), the number of relapses, and the number of DALYs, were estimated. DALY was calculated as the sum of the years of life lost (YLL) due to premature mortality and years lived with disability (YLD). Societal outcomes that were reported included productivity measure (% employed and % retired early) and informal care days per annum. Economic outcomes included direct, relapse, and indirect costs. Direct costs comprised healthcare costs (disease management, drug administration and monitoring, AE management, and non-medical) and excluded DMT acquisition costs. The drug acquisition costs were not considered in the model because the net drug acquisition cost of any drug (in this case ofatumumab and teriflunomide) is confidential in Spain. Relapse costs were those associated with the management of relapse events. Indirect costs referred to costs due to productivity losses incurred by patients and caregivers. All cost estimates were reported in 2020 euros using the Spanish consumer price index dataCitation41.

Results

Clinical outcomes

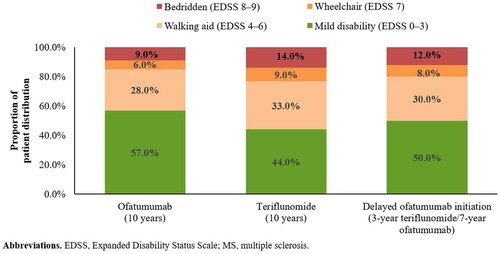

At the end of 10 years, the proportion of patients in a mild disability state (EDSS 0–3) were projected to be higher in the ofatumumab cohort than in the teriflunomide cohort (57.0% vs 44.0%). Compared with early ofatumumab initiation, a 3-year delay in ofatumumab initiation (i.e. as the first treatment after diagnosis) was found to result in an 11.4% reduction in the proportion of patients in a mild disability state ().

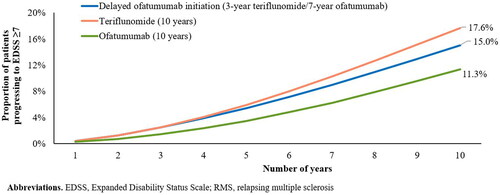

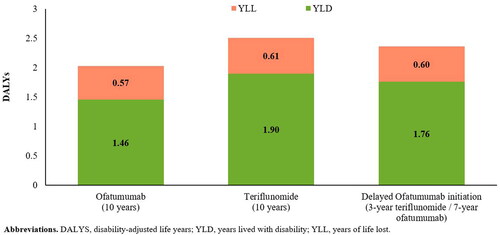

Over 10 years, the proportion of patients requiring a wheelchair or bedridden (EDSS ≥ 7) was projected to be lower in the ofatumumab cohort than in the teriflunomide cohort (11.3% vs 17.6%) (). Furthermore, patients in the ofatumumab cohort were projected to experience 27.8% fewer relapses (3.8 vs 5.3) and 19% fewer DALYs (2.0 vs 2.5) vs those in the teriflunomide cohort. The difference in the number of DALYs was mainly due to differences in YLD, which was considerably lower in the ofatumumab cohort than in the teriflunomide cohort (1.46 vs 1.90) (). Compared with early ofatumumab initiation, a 3-year delay in initiation was estimated to result in 32.2% more patients progressing to EDSS ≥ 7 (), 20.2% more relapses (4.6 vs 3.8), and 16.6% more DALYs over 10 years ().

Societal outcomes

At the end of 10 years, the proportion of patients who were employed was projected to be higher (40.0% vs 35.2%) and that of patients who retired early was relatively lower (13.0% vs 15.4%) in the ofatumumab cohort than in the teriflunomide cohort. Additionally, patients in the ofatumumab cohort were projected to require 7.3% reduced informal care time than those in the teriflunomide cohort (1,542 vs 1,664 days). A 3-year delay in ofatumumab initiation was projected to result in lower productivity (i.e. 6% less employed; 9.1% retired early) and 5.4% increased informal care time (1,625 vs 1,542 days) in patients receiving delayed vs early ofatumumab initiation.

Economic outcomes

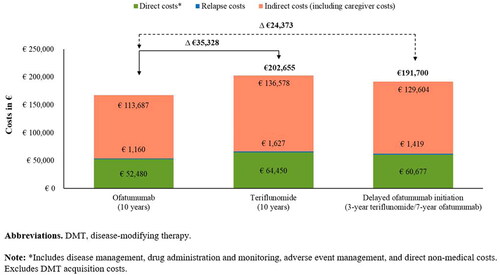

Over 10 years, patients in the ofatumumab cohort were estimated to incur 17.4% lower costs than those in the teriflunomide cohort (€167,327 vs €202,655 per patient). Additionally, a 3-year delay in ofatumumab initiation was projected to result in an incremental cost of €24,373 per patient compared with early ofatumumab initiation (191,700 vs 167,327 per patient over 10 years) (). In line with the clinical and societal outcomes, a 3-year delay in ofatumumab initiation was projected to result in 14.6% more costs compared with early ofatumumab initiation (€191,700 vs €167,327 per patient). Indirect costs accounted for two-thirds of the total costs, whereas direct costs (excluding DMT acquisition costs) accounted for one-third. Across the three scenarios, disease management and non-medical costs were the key contributors to the direct costs, while costs associated with productivity loss (short- and long-term absence from work, invalidity, and early retirement) accounted for most of the total indirect costs (Supplementary Table S3).

Discussion

Based on the results from this cost-consequence economic modeling analysis, early initiation of HET such as ofatumumab, compared with its delayed initiation, was found to be an effective and cost-saving strategy for improving the long-term (i.e. 10 years) outcomes in RMS patients. Furthermore, patients receiving ofatumumab for long-term (i.e. 10 years) were projected to experience better outcomes (clinical, societal, and economic) than those receiving teriflunomide among RMS patients from a Spanish societal perspective.

The therapeutic landscape of MS has witnessed a discernible shift in the last decade with the availability of multiple HETsCitation42. Evidence supporting the early initiation of HETs, contrary to a treatment escalation approach, continues to accumulate with benefits to both the patients and societyCitation5–9,Citation19–22. A population-based Danish Multiple Sclerosis Registry study showed a lower risk of 6-month EDSS worsening (16.7% vs 30.2%) and first relapse (HR: 0.50, 95% confidence interval: 0.37–0.67) in patients initiated on HET as the first therapy vs a matched cohort initiated on a moderate-efficacy DMTCitation19. Data from two cohort studies from the UK and Italy reported that long-term trajectories are more favorable with an early intensive therapy strategy than with moderate-efficacy DMTsCitation5,Citation6. Similarly, data from a retrospective international observational study showed that commencement of HETs within 2 years of disease onset was associated with lesser disability after 6–10 years compared with commencement later in the disease course in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis patientsCitation7. Despite the growing body of evidence in favor of early initiation of HETs, widespread use of high-efficacy DMTs as the first-line treatment in newly-diagnosed MS patients has not yet been established as the standard treatment paradigm. Moreover, most treatment guidelines recommend initiating moderate-efficacy DMTs in patients with mild-to-moderate disease activity, while HETs are often reserved for later use in the disease course or for highly active patients with a rapidly evolving aggressive diseaseCitation43–46.

Data from this cost-consequence analysis showed that, over 10 years, patients in the ofatumumab cohort experienced better health outcomes, i.e. a lower proportion of patients required a wheelchair or were bedridden (EDSS ≥ 7), reduced relapse rates, lower disability states (i.e. fewer number of DALYs), lesser informal care time, and higher productivity, compared with those in the teriflunomide cohort. This was also reflected by a higher proportion of patients in the ofatumumab cohort maintaining a mild disability state over the 10 years than those in the teriflunomide cohort. The results of this study are in line with those of previous studies that reported favorable long-term health benefits (delayed disability progression, reduced relapse rates, increased likelihood of achieving no evidence of disease activity, increased work attendance and work productivity, and lower work productivity activity impairment) with the initiation of HETs compared with other moderate-efficacy DMTsCitation5,Citation6,Citation9,Citation21,Citation47–50. In addition to the health benefits, our model estimated that 10-year ofatumumab treatment led to a considerable cost-saving compared with teriflunomide treatment (Δ €35,328 per patient).

We further explored the implications of early vs delayed ofatumumab initiation. As expected, a 3-year delay in ofatumumab initiation was found to impose an incremental health (32.2% more patients progressing to EDSS ≥ 7, 20.2% more relapses, 5.4% increased informal care time, and 16.6% more DALYs) and cost (14.6% more healthcare costs) burden compared with its early initiation. These results highlight the potential health and socioeconomic merits of early vs delayed ofatumumab initiation. A direct comparison of our findings with those of other studies is not possible as this is the first study to explore the impact of early vs delayed ofatumumab initiation. However, we can benchmark the results with a few existing studies that have reported the positive benefits of early vs delayed initiation of HETsCitation5–8,Citation19,Citation21,Citation22.

This study has a few limitations. First, the baseline characteristics, natural history data, and efficacy were based on data from the ASCLEPIOS I and II trials, which included patients from multiple countries. Moreover, Spanish MS patients accounted for approximately 5% of the population in ASCLEPIOS trials; thus, the patient population included in this analysis and their characteristics may not be representative of the broader Spanish population. The model can be updated once Spanish-specific data are available. Productivity-related inputs were sourced from a cross-sectional retrospective studyCitation37, which had limitations including small subsets of patients in moderate (29%) and severe (11%) disability states and data for moderate and severe states being underestimated compared to those reported in the UK studyCitation38. Moreover, Oreja-Guevara et al.’s studyCitation37 reported estimates as per mild (EDSS 0–3), moderate (EDSS 4–6.5), and severe (EDSS 7–9) and does not provide inputs as per EDSS (as required for cost-consequence analysis); therefore, regression was fitted to derive inputs. Although this method provides EDSS-wise inputs, this is further hampered by the small sample size of the study. The disability weights used to derive DALYs were from a Korean study and may not be generalizable to Spanish settingsCitation36. The Markov model is based on EDSS health states, which focus on functional mobility and are insensitive to cognitive impairments; therefore, there are limitations inherent to the Markov model, such as being memoryless and the transition probabilities used in the model might not reflect actual patient movement in clinical practice. These issues are relevant to most current models of MS disease. The data on age- and gender-specific mortality rates considered in the model were derived from Office for National Statistics reference 2021Citation34 and are assumed to be the same over the entire time horizon of the model. This is a limitation that commonly exists in cost-effectiveness and cost-consequence analysis whose time horizon is long. However, its impact on results may be negligible as same age- and gender-specific mortality rates were applied to both cohorts (i.e. patients on ofatumumab and teriflunomide). Finally, the cost savings presented in this study may vary as we did not include drug acquisition costs, which means that, while all other medical costs can be assessed, the overall treatment costs cannot be compared.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study highlights the benefits of early initiation of HETs such as ofatumumab vs its delayed initiation for improving outcomes in RMS patients (having characteristics similar to those of patients included in the ASCLEPIOS trials). Based on the results of this economic modeling analysis, ofatumumab treatment was projected to improve the long-term clinical, societal, and economic outcomes, compared with teriflunomide treatment, in RMS patients from a Spanish societal perspective.

Transparency

Declaration of financial/other interests

UV, MP, KG, EK, and NA are employees of Novartis.

Author contributions

UV, KG, EK, and NA were responsible for the conception and design of the project. UV, MP, and KG were responsible for the analysis and development of the model. All authors participated in critically reviewing and interpreting the data. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript for intellectual content and all authors approved the final version for publication submission. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Reviewer disclosures

A reviewer on this manuscript has disclosed that they consult for MS pharma including Novartis and Genzyme Sanofi; they have also advised on ASCLEPIOS. All the peer reviewers on this manuscript have received an honorarium from JME for their review work but have no other relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Previous presentations

Study results were previously presented at the 37th Congress of the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis (virtual) held between 13 and 15 October 2021.

Supplemental Material

Download JPEG Image (69.9 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (26.9 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Santosh Tiwari (Novartis Healthcare Pvt. Ltd., Hyderabad) for providing medical writing support for this manuscript.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Fernández O, Fernández V, Guerrero M, et al. Multiple sclerosis prevalence in Malaga, Southern Spain estimated by the capture-recapture method. Mult Scler. 2012;18(3):372–376.

- Multiple Sclerosis International Federation (MSIF). Atlas of MS. 2013. [cited 2021 Nov 28]. https://www.msif.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Atlas-of-MS.pdf

- Fernández O, Calleja-Hernández MA, Meca-Lallana J, et al. Estimate of the cost of multiple sclerosis in Spain by literature review. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2017;17(4):321–333.

- Filippi M, Danesi R, Derfuss T, et al. Early and unrestricted access to high-efficacy disease-modifying therapies: a consensus to optimize benefits for people living with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 2022;269(3):1670–1677.

- Iaffaldano P, Lucisano G, Caputo F, et al. Long-term disability trajectories in relapsing multiple sclerosis patients treated with early intensive or escalation treatment strategies. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2021;14:175628642110195.

- Harding K, Williams O, Willis M, et al. Clinical outcomes of escalation vs early intensive disease-modifying therapy in patients with multiple sclerosis. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(5):536–541.

- He A, Merkel B, Brown JWL, et al. Timing of high-efficacy therapy for multiple sclerosis: a retrospective observational cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(4):307–316.

- Merkel B, Butzkueven H, Traboulsee AL, et al. Timing of high-efficacy therapy in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Autoimmun Rev. 2017;16(6):658–665.

- Simonsen CS, Flemmen HØ, Broch L, et al. Early high efficacy treatment in multiple sclerosis is the best predictor of future disease activity over 1 and 2 years in a Norwegian population-based registry. Front Neurol. 2021;12:693017.

- Scolding N, Barnes D, Cader S, et al. Association of British Neurologists: revised (2015) guidelines for prescribing disease-modifying treatments in multiple sclerosis. Pract Neurol. 2015;15(4):273–279.

- Marques VD, Passos GRD, Mendes MF, et al. Brazilian consensus for the treatment of multiple sclerosis: Brazilian Academy of Neurology and Brazilian Committee on treatment and research in multiple sclerosis. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2018;76(8):539–554.

- Grand’Maison F, Yeung M, Morrow SA, et al. Sequencing of high-efficacy disease-modifying therapies in multiple sclerosis, perspectives and approaches. Neural Regen Res. 2018;13(11):1871–1874.

- Inshasi JS, Almadani A, Fahad SA, et al. High-efficacy therapies for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: implications for adherence. An expert opinion from the United Arab Emirates. Neurodegener Dis Manag. 2020;10(4):257–266.

- Samjoo IA, Worthington E, Drudge C, et al. Efficacy classification of modern therapies in multiple sclerosis. J Comp Eff Res. 2021;10(6):495–507.

- Margoni M, Preziosa P, Filippi M, et al. Anti-CD20 therapies for multiple sclerosis: current status and future perspectives. J Neurol. 2022;269(3):1316–1334.

- European Medicines Agency. Ofatumumab (Kesimpta). [cited 2021 Sep 15]. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/overview/kesimpta-epar-medicine-overview_en.pdf

- Gartner J, Hauser S, Bar‐Or A, et al. Benefit-risk of ofatumumab in treatment-naïve early relapsing multiple sclerosis patients. Mult Scler J. 2020;26(3 suppl):210.

- Hauser SL, Bar-Or A, Cohen JA, et al. Ofatumumab versus teriflunomide in multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(6):546–557.

- Buron MD, Chalmer TA, Sellebjerg F, et al. Initial high-efficacy disease-modifying therapy in multiple sclerosis: a nationwide cohort study. Neurology. 2020;95(8):e1041–e1051.

- Kavaliunas A, Manouchehrinia A, Stawiarz L, et al. Importance of early treatment initiation in the clinical course of multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2017;23(9):1233–1240.

- Prosperini L, Mancinelli CR, Solaro CM, et al. Induction versus escalation in multiple sclerosis: a 10-year real world study. Neurotherapeutics. 2020;17(3):994–1004.

- Spelman T, Magyari M, Piehl F, et al. Treatment escalation vs immediate initiation of highly effective treatment for patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: data from 2 different national strategies. JAMA Neurol. 2021;78(10):1197–1204.

- Mauskopf JA, Paul JE, Grant DM, et al. The role of cost-consequence analysis in healthcare decision-making. Pharmacoeconomics. 1998;13(3):277–288.

- European Medicines Agency. Teriflunomide (Aubagio) summary of product characteristics. [cited 2021 Sep 15]. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/aubagio-epar-product-information_en.pdf

- Taheri S, Sahraian MA, Yousefi N. Cost-effectiveness of alemtuzumab and natalizumab for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis treatment in Iran: decision analysis based on an indirect comparison. J Med Econ. 2019;22(1):71–84.

- Baharnoori M, Bhan V, Clift F, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of ofatumumab for the treatment of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis in Canada. Pharmacoecon Open. 2022;6(6):859–870.

- Versteegh MM, Huygens SA, Wokke BWH, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of 360 disease-modifying treatment escalation sequences in multiple sclerosis. Value Health. 2022;25(6):984–991.

- Canadian Agency for Drugs & Technologies in Health (CADTH). CADTH common drug review. Pharmacoeconomic review report Ocrelizumab (Ocrevus) version 1.0. 2017. [cited 2022 Oct 31]. Available from: https://www.cadth.ca/sites/default/files/cdr/pharmacoeconomic/SR0519_Ocrevus_RMS%20_PE_Report.pdf

- Palace J, Bregenzer T, Tremlett H, et al. UK multiple sclerosis risk-sharing scheme: a new natural history dataset and an improved markov model. BMJ Open. 2014;4(1):e004073.

- Scalfari A, Neuhaus A, Degenhardt A, et al. The natural history of multiple sclerosis: a geographically based study 10: relapses and long-term disability. Brain. 2010;133(Pt 7):1914–1929.

- Orme M, Kerrigan J, Tyas D, et al. The effect of disease, functional status, and relapses on the utility of people with multiple sclerosis in the UK. Value Health. 2007;10(1):54–60.

- Patzold U, Pocklington PR. Course of multiple sclerosis. First results of a prospective study carried out of 102 MS patients from 1976–1980. Acta Neurol Scand. 1982;65(4):248–266.

- Samjoo IA, Worthington E, Drudge C, et al. Comparison of ofatumumab and other disease-modifying therapies for relapsing multiple sclerosis: a network meta-analysis. J Comp Eff Res. 2020;9(18):1255–1274.

- Office for National Statistics reference. Spain life expectancy. [cited 2021 Sep 20]. Available from: https://www.ine.es/en/index.htm

- Pokorski RJ. Long-term survival experience of patients with multiple sclerosis. J Insur Med. 1997;29(2):101–106.

- Cho JY, Hong KS, Kim HJ, et al. Disability weight for each level of the Expanded Disability Status Scale in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2014;20(9):1217–1223.

- Oreja-Guevara C, Kobelt G, Berg J, et al. New insights into the burden and costs of multiple sclerosis in Europe: results for Spain. Mult Scler. 2017;23(2_suppl):166–178.

- Thompson A, Kobelt G, Berg J, et al. New insights into the burden and costs of multiple sclerosis in Europe: results for the United Kingdom. Mult Scler. 2017;23(2_suppl):204–216.

- Gisbert R, Brosa M. Spanish health costs and cost-effectiveness ratios database: ESALUD [Online]. [cited 2021 Sep 20]. Available from: http://esalud.oblikue.com/

- Hawton AJ, Green C. Multiple sclerosis: relapses, resource use, and costs. Eur J Health Econ. 2016;17(7):875–884.

- The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. [cited 2021 Sep 20]. Available from: https://www.oecd.org/spain/

- Simpson A, Mowry EM, Newsome SD. Early aggressive treatment approaches for multiple sclerosis. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2021;23(7):19.

- García Merino A, Ara Callizo JR, Fernández Fernández O, et al. Consensus statement on the treatment of multiple sclerosis by the Spanish Society of Neurology in 2016. Neurologia. 2017;32(2):113–119.

- Montalban X, Gold R, Thompson AJ, et al. ECTRIMS/EAN guideline on the pharmacological treatment of people with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2018;24(2):96–120.

- Rae-Grant A, Day GS, Marrie RA, et al. Practice guideline recommendations summary: disease-modifying therapies for adults with multiple sclerosis: report of the guideline development, dissemination, and implementation subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2018;90(17):777–788.

- Wiendl H, Gold R, Zipp F. Multiple sclerosis therapy consensus group (MSTCG): answers to the discussion questions. Neurol Res Pract. 2021;3(1):44.

- Bosco-Lévy P, Debouverie M, Brochet B, et al. Comparative effectiveness of dimethyl fumarate in multiple sclerosis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2022;88(3):1268–1278.

- Chen J, Taylor BV, Blizzard L, et al. Effects of multiple sclerosis disease-modifying therapies on employment measures using patient-reported data. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2018;89(11):1200–1207.

- Lee A, Pike J, Edwards MR, et al. Quantifying the benefits of dimethyl fumarate over β interferon and glatiramer acetate therapies on work productivity outcomes in MS patients. Neurol Ther. 2017;6(1):79–90.

- Neuberger EE, Abbass IM, Jones E, et al. Work productivity outcomes associated with ocrelizumab compared with other disease-modifying therapies for multiple sclerosis. Neurol Ther. 2021;10(1):183–196.