?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Objective

In Canada, a persistent barrier to achieving healthcare system efficiency has been patient days accumulated by individuals with an alternate level of care (ALC) designation. Transitional care units (TCUs) may address the capacity pressures associated with ALC. We sought to assess the cost-effectiveness of a nursing home (NH) based TCU leveraging existing infrastructure to support a hospitalized older adult’s transition to independent living at home.

Methods

This case-control study included frail, older adults who received care within a function-focused TCU following a hospitalization between 1 March 2018 and 30 June 2019. TCU patients were propensity score matched to hospitalized ALC patients (“usual care”). The primary outcome was days without requiring institutional care six months following discharge, defined as institutional-free days. This was calculated by excluding all days in hospitals, rehabilitation facilities, complex continuing care facilities and NHs. Using the total direct cost of care up to discharge from TCU or hospital, the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio was calculated.

Results

TCU patients spent, on average, 162.0 days institution-free (95% CI: 156.3–167.6d) within six months days post-discharge, while usual care patients spent 140.6 days institution-free (95% CI: 132.3–148.8d). TCU recipients had a lower total cost of care, by CAN$1,106 (95% CI: $–6,129–$10,319), due to the reduced hospital length of stay (mean [SD] 15.6d [13.3d] for TCU patients and 28.6d [67.4d] days for usual care). TCU was deemed the more cost-effective model of care.

Limitations

The main limitation was the potential inclusion of patients not eligible for SAFE in our usual group. To minimize this selection bias, we expanded the geographical pool of ALC patients to patients with SAFE admission potential in other area hospitals.

Conclusions

Through rehabilitative and restorative care, TCUs can reduce hospital length of stay, increase potential for independent living, and reduce risk for subsequent institutionalization.

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY

A persistent barrier to achieving efficiency within the Canadian healthcare system has been days accumulated by patients who no longer require the intensity of hospital care but are waiting to be discharged to more appropriate care settings. Prolonged hospital stays are known to expose patients to various health risks.

Transitional care units are care settings designed to improve care continuation for patients moving between different locations or levels of care. They an opportunity to address the capacity pressures and health risks associated with prolonged hospital stays.

Studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of transitional care units to improve outcomes among older adults, such as reducing hospital length of stay, nursing home placement, and falls, as well as improving functional status, quality of life, and likelihood of being discharged home. However, the financial implications of transitional care units, in terms of resources required to operate their services, and value for money are not well understood.

This study found that a nursing home-based, function-focused transitional care unit reduced the length of stay in hospitals and the risk for subsequent institutionalization among frail, older adults. This was achieved at a lower total cost of care. Older adults who received transitional care were able to remain at home for three weeks longer without requiring institutional care compared to those who did not receive transitional care. Considering the growing investments in transitional care, this research provides evidence supporting nursing home-based transitional care programs.

Introduction

A central indicator of healthcare system efficiency is timely access to careCitation1. In Canada, a persistent barrier to achieving such efficiency has been patient-days accumulated by individuals waiting to be discharged from the hospital to a more appropriate care settingCitation1. Alternate level of care, or ALC, is a designation given to patients who no longer require the intensity of services or resources provided in hospital but, due to inadequate community-based services or continuing post-acute care requirementsCitation2, are unable to be discharged. Patients designated ALC, many of whom are older, accounted for nearly 16% of patient-days in hospitals in 2019 in CanadaCitation3.

The health risks of prolonged hospital stays are also well-documented. Extended hospitalization is associated with an elevated risk of deconditioning (particularly for frail older adults), exposure to hospital-acquired infections, and social isolationCitation4–9. Functional decline associated with prolonged hospital stays may prevent the return to independent living, lead to premature admission to institutional care and contribute to hospital readmissionsCitation10,Citation11.

Transitional care—also known as intermediate care, post-acute care, subacute care or convalescent care—offers a potential opportunity to address the capacity pressures and health risks associated with prolonged hospital stays. Transitional care units (TCUs) are designed to improve care continuation for patients moving between different locations or levels of careCitation12,Citation13. They can support the timely discharge of patients and ensure care is received in more appropriate settings. TCUs frequently prioritize rehabilitative care to restore independenceCitation14. This approach is rooted in evidence demonstrating the beneficial effects of rehabilitative care for older adults, particularly frail adults with restorative potentialCitation15.

Existing studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of TCUs in improving outcomes among older adults in Canada and abroad, such as reducing hospital length of stayCitation16–20, nursing home placementCitation21,Citation22 and fallsCitation20, as well as improving functional statusCitation16,Citation20,Citation22, care qualityCitation23, quality of lifeCitation24 and the likelihood of being discharged homeCitation20,Citation23. However, the financial implications of TCUs, in terms of resources required to establish and operate the services and value for money, is less understoodCitation25. Of 37 studies included in a scoping review on TCUs for older adults, only 9 considered costs in addition to outcomes, with 6 concluding TCUs to be cost-effectiveCitation14. This review also found that TCUs were more expensive in three studies due to longer hospital staysCitation14. Considering the growing investments into TCUs in Canada, including OntarioCitation26, a cost-effectiveness study is warranted to inform decision-makers of the value of such programs. The objective of this study was to assess the cost-effectiveness of a nursing home-based TCU, located in the capital city of Canada.

Methods

Study design and data sources

We conducted a cost-effectiveness study of the Sub-Acute care for Frail Elderly (SAFE) Unit, a TCU in Ottawa, Canada, compared to usual care from the perspective of the public payer (Ontario Health). The timeframe of this study was six months (180 days) post-discharge. We linked health administrative databases housed at ICES, an independent non-profit research organization, to facility-level data from SAFE to enable prospective observation of patients’ post-discharge healthcare use and outcomes. These datasets were linked using unique encoded identifiers and analyzed at ICES. See Table S1 (Supplemental Digital Content 1) for a description of databases used. This study adheres to the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS)Citation27.

Setting

SAFE was a 20-bed function-focused TCU established in 2018 at Perley Health, a large 450-bed nursing home in Ottawa, Ontario, CanadaCitation28. As a collaborative model between acute care and a nursing home provider, the primary goal of the program was to restore independence, allowing patients to return home following acute care discharge through an inter-professional team approach and specialized training in sub-acute careCitation28. Eligible patients were medically complex older adults at risk of deconditioning in hospital but expected to return home in the community or to a retirement homeCitation28. A recent study by Robert et al. demonstrated that patients discharged from SAFE were less likely to be discharged to settings other than home and had shorter hospital staysCitation29.

Study cohort

SAFE patients included those who received transitional care at Perley Health following a hospitalization between 1 March 2018 and 30 June 2019. See Table S2 (Supplemental Digital Content 1) for SAFE Unit admission criteria. Our comparison group (or “usual” care) consisted of hospitalized patients designated as ALC within the same period, who did not receive transitional care at SAFE. As previous research has found variations in the level and types of rehabilitation services and home care provided across different regions in OntarioCitation30–32, a contextual risk factor for ALCCitation33–35, we limited the selection of the usual care group to individuals who had been designated ALC for at least one day in a hospital within the same health region as SAFE (i.e. the Ontario East Home and Community Care Support Services (HCCSS) formerly known as the Champlain Local Health Integration Network (LHIN)). This analysis only included SAFE and usual care patients who survived the full 180-days post-discharge to ensure all patients included were eligible for the primary outcome, institution-free days.

Measurement of effectiveness

Hospital-free days has been utilized in healthcare and clinical research, including clinical trials, as a patient-centred, objective, clinically meaningful and reliable outcome measureCitation36–38. This is based on the premise that most patients have a strong preference for longer lives and to have those days take place outside of hospitalsCitation36–38. As such, the overall success of a healthcare intervention may be measured by days at home, days out of hospital, treatment-free days, and other related metricsCitation36–38. These metrics are often readily available in administrative healthcare databases and demonstrate improved external validity relative to a disease- or intervention-specific outcomeCitation38.

We selected institution-free days within 180 days post-discharge from SAFE (for SAFE patients) or from hospital (for usual care patients) as the measure of effectiveness. One of the considerations for a patient’s admission to SAFE is their desire to return to their private residence post-discharge (Table S2). While this may not be the preference of all older adults in our control group (i.e. those who received usual care), we believe institution-free days is an appropriate outcome for our evaluation as it is one of the goals of care for those who received care in SAFE. This outcome is a broader measure of hospital-free days through the inclusion of other types of institutional care. Specifically, institutional care was defined as services provided in hospitals (including acute care and mental health hospitals), rehabilitation facilities, complex continuing care facilities and nursing homes.

Measurement of cost

Costs included those borne to Ontario Health and incurred during the index hospitalization up to discharge from SAFE (for SAFE patients) or hospital (for usual care patients). The per diem cost for SAFE was $439.65. A detailed breakdown of the cost components of SAFE and a description of the costing methodology for costs incurred during index hospitalization can be found in Table S3 (Supplemental Digital Content 1). Costs were presented in 2019 Canadian dollars.

Analysis

We estimated net costs and net effectiveness using a propensity-matching approach. To create a matched cohort, SAFE patients were first hard-matched 1:1 to usual care patients on age, specified continuously as a whole number, and sex. Then, SAFE and usual care patients were matched using propensity scores estimated from a logistic regression, with admission to SAFE as the dependent variable. Propensity score matching was performed to obtain a more balanced dataset that minimizes selection bias. Based on prior research on risk factors for hospital readmission and nursing home admissionsCitation39–46, we included the following variables in the propensity model: the patients’ medical complexity (measured using the Johns Hopkins ACG System Version 10); rurality of their residence (a proxy for access to home and community support); prior acute care admission within six months before index admission; as well as several specific comorbidities (stroke, dementia, arrhythmia, congestive heart failure [CHF], chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD] and lower respiratory tract infection). ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes are assigned to one of 32 Aggregated Diagnosis Groups (ADGs) within the ACG SystemCitation47. Five clinical factors of the condition (duration, severity, diagnostic certainty, aetiology and specialty care involvement) are considered when diseases or conditions are assigned to one of the 32 ADG clustersCitation47. We used the total number of ADGs with a lookback period of two years as a measure of the patients’ medical complexity, as the ACG score is a widely recognized indicator for measuring medical complexity in older adultsCitation48–52. The overall ACG score was used to control for heterogeneity in frailty and medical complexity between the two groups, as they would not be balanced otherwise. The aforementioned variables were reviewed by the Medical Director of SAFE (the senior author of this study) to ensure the matching algorithm included variables that informed a recommendation for patient admission to SAFE. Although this may be vulnerable to subjectivity, as in all clinical judgments, the Medical Director is a recognized expert in the field and a decision-maker involved in admissions to SAFE.

We employed nearest neighbour calliper matching, using callipers of width equal to 0.2 of the standard deviation (SD) of the logit of propensity scores, without replacement and with subjects selected in random order, as recommended by AustinCitation53. Balance in baseline characteristics between SAFE patients and usual care patients was evaluated using standardized differences with a threshold of 0.1. Net benefit was calculated by subtracting the number of institution-free days incurred by usual care patients from the number of institution-free days incurred by SAFE patients. Net cost was similarly calculated by subtracting the total cost of care for usual care patients from the total cost of care for SAFE patients. 95% confidence intervals around the difference in means were calculated using 5,000 bootstrapped samples.

Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio

We calculated the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of transitional care on institution-free days. This represents the additional cost for each additional institution-free day in the community by providing transitional care in the SAFE Unit. The ICER estimate was obtained by dividing net costs by net effectiveness, as displayed in EquationEquation (1)(1)

(1) below:

(1)

(1)

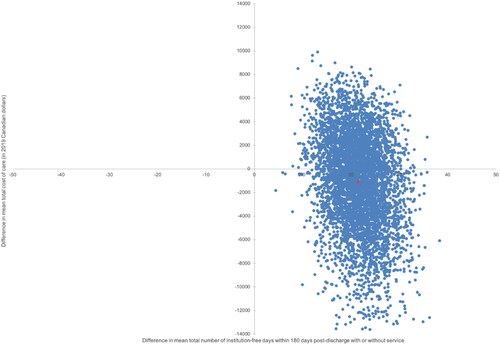

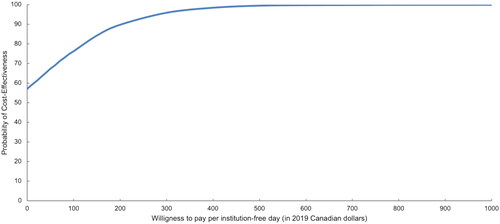

A bootstrap sample without replacement with 5,000 iterations was performed to represent the statistical uncertainty around the estimated ICER. Bootstrapped ICERs (pairs of effectiveness and cost) were plotted on a cost-effectiveness plane to graphically represent the differences in effectiveness (on the x-axis) and costs (on the y-axis). A cost-effectiveness acceptability curve was also plotted to visualize the probability that the intervention was cost-effective based on various willingness-to-pay thresholds. That is, if the government had a willingness-to-pay of a certain price, per outcome (institution-free day), the curve plots the probability that the ICER falls below this price.

Scenario analysis

We conducted a scenario analysis to verify the robustness of our findings using a more stringent measure of effectiveness; in this case, institution-free days without any services within 180-days post-discharge from the index event. This was performed as the need for home and community care support is often used as an indicator of functional dependence. Our definition of service-free days excluded days where care was received in hospitals, rehabilitation facilities, nursing homes as well as days where the patient received any home care services, primary care visits or was admitted to the emergency department (ED).

Ethics approval

ICES is a prescribed entity under section 45 of Ontario’s Personal Health Information Protection Act. Section 45 authorizes ICES to collect personal health information, without consent, for the purpose of analysis or compiling statistical information with respect to the management of, evaluation or monitoring of, the allocation of resources to or planning for all or part of the health system. Projects conducted under section 45 and have received approval by ICES’ Privacy and Legal Office, such as this one, do not require review by a Research Ethics Board.

Results

summarizes the sociodemographic characteristics of SAFE and usual care patients in the unmatched and matched cohorts across variables included in our propensity model. The unmatched cohort comprised 155 SAFE patients and 3,336 usual care patients. The matched cohort comprised 154 SAFE patients and 154 usual care patients. One SAFE patient was not matched due to a lack of suitable controls. See Figure S1 (Supplemental Digital Content 1) for cohort creation. Prior to matching, nearly all variables, with the exception of sex, were imbalanced with a standard difference exceeding 0.1 (), a suggested threshold for imbalanceCitation54. Post-matching, all variables were well balanced with a standard difference less than or equal to 0.1.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of SAFE Unit and usual care patients, before and after matching.

The matched cohort had a mean (SD) age at discharge of 82.5 years (9.0) for both SAFE and usual care patients, were mostly female (61.0%), and comprised mostly residents in urban centres (upwards of 96%). Among the included comorbidities, CHF was the most prevalent condition (55.8% and 54.5%) followed by COPD (33.1% and 30.5%). The mean (SD) ACG score was 13.7 (3.2) for SAFE patients and 13.9 (3.2) for usual care patients. The majority of SAFE and usual care patients did not have a prior acute care admission within six months of index (64.9% and 66.2%), while many had a lower respiratory tract infection (31.8% and 30.5%).

The care trajectory of patients admitted to SAFE from admission to the hospital up to discharge from SAFE is presented in Figure S2 (Supplemental Digital Content 1). The mean (SD) total length of stay in SAFE was 21.8 days (12.0). SAFE patients’ length of stay during index hospitalization was half the length of usual care patients (mean [SD]: 15.6 days [13.3] vs. 28.6 days [67.4]), while the length of stay in ALC for SAFE patients was less than a third in length compared to usual care patients (3.4 days [10.8] vs. 11.3 days [28.8]) (Figure S3, Supplemental Digital Content 1).

Effectiveness: institutional-free days

As shown in , SAFE patients spent, on average, 162.0 institution-free days (95% CI: 156.3–167.6 days) in the community within 180-days post-discharge, while usual care patients had an average of 140.6 institution-free days (95% CI: 132.3–148.8 days). The majority of institutional days for SAFE patients were spent in an acute care hospital (9.8 days, 95% CI: 6.8–12.8 days), while nursing homes accounted for the majority of institutional days among usual care patients (14.2 days, 95% CI: 7.9–20.6 days) (). The use of the rehabilitation facilities was almost completely prevented after SAFE (1.1 days, 95% CI: 0.3–1.8 days) while usual care patients spent, on average, 9.5 days (95% CI: 6.8–12.2 days) in such facilities ().

Table 2. Breakdown of effectiveness and cost (in CAD$2019).

Table 3. Breakdown of service use (in days) within 180 days post-discharge.

Cost

Costs of care for SAFE and usual care patients are displayed in . The mean total cost of the index hospitalization was lower among SAFE patients, at CAN$13,604 (95% CI: $11,559–$15,649), compared to usual care patients at CAN$24,294 (95% CI: $16,208–$32,379), given their overall shorter length of stay in hospital (Figure S3, Supplemental Digital Content 1). The mean total cost of care in the SAFE Unit was CAN$9,584 (95% CI: $8,741–$10,426). As the hospital cost savings that may have been gained from the shorter length of stay in their index hospitalization exceed the cost of care in the SAFE Unit, SAFE patients had a lower mean total cost at CAN$23,188 (95% CI: $20,895–$25,481) compared to CAN$24,294 (95% CI: $16,208–$32,379) for the usual care group, suggesting that the SAFE Unit was cost-saving compared to usual care by CAN$1,106 (95% CI: −$6,129–$10,319).

Cost-effectiveness analysis

As SAFE patients had more institution-free days and incurred a lower total cost of care, it was deemed as the more cost-effective (dominant) model of care. presents the distribution of the incremental benefit (95% CI: 12.3–31.0 days) and cost (95% CI: CAN$-10,319–$6,129) estimates from 5,000 bootstrap samples. All estimated cost-effectiveness pairs fell in the north-east or south-east quadrant indicating SAFE was more effective than usual care with respect to institution-free days; however, SAFE was associated with lower cost than usual care in 57% of the bootstrapped samples. The cost-effectiveness acceptability curve presented in indicates that if the willingness to pay is greater than $941 per institution-free day, SAFE is cost-effective 100% of the time. Even when we applied a more stringent definition of service-free days, by excluding community-based care services, SAFE remained cost-effective. See Table S4 (Supplemental Digital Content 1) for scenario analysis, Figure S4 (Supplemental Digital Content 1) for the cost-effectiveness plan and Figure S5 (Supplemental Digital Content 1) for the cost-effectiveness acceptability curve.

Discussion

Our analyses suggest that receiving care in a TCU, like SAFE, is a cost-effective model of care as it enables older frail patients to remain longer in the community at a lower cost. In our base case, we observed SAFE patients spent three additional weeks in the community institution-free compared to usual care patients. Nearly half of this difference was attributable to the greater number of days usual care patients spent in nursing homes. SAFE patients also had a shorter length of stay, by nearly two weeks, during the index hospitalization. The use of rehabilitation facilities was also almost entirely prevented among SAFE patients following discharge, possibly as a result of the SAFE Unit’s interdisciplinary approach to care which emphasizes both rehabilitative and restorative care.

These results are in line with the findings from our previous analysis, which found SAFE patients spent fewer days in the hospital and in an ALC bed during their index hospitalizationCitation29. The previous analysis also found higher odds of a readmission within 30 days (OR: 1.41, 95% CI: 0.8–2.31) among SAFE patientsCitation29. Although this result was not statistically significant, the elevated odds ratio may be a reflection of the higher level of frailty and medical complexity of SAFE patients. While we controlled for heterogeneity between SAFE and usual care patients in our regression model, we did not attempt to match them. Our earlier observations informed the approach for this paper, to use propensity score matching to create a more comparable control group. Utilizing a timeframe that would allow us to observe longer-term outcomes, the findings presented here are similar to our initial investigation, whereby SAFE patients continue to experience higher odds of re-admission and spend more days in the hospital than patients under usual care. However, they are much less likely to require long-term institutional care, such as care provided in other sub-acute complex continuing care facilities and in nursing homes. This suggests that the benefits of SAFE for this highly frail and medically complex population may not be in the mitigation of acute care use, which may be entirely unavoidable, but to lessen their likelihood of further functional deterioration and needing residential care.

With respect to the cost of providing transitional care, the cost of SAFE was fully offset by the savings incurred during the index hospitalization. However, the difference in costs was associated with some level of uncertainty, and it was possible that the unit might be associated with higher costs compared to usual care. This was not unexpected given that most new interventions and models of care within healthcare are expected to incur a higher cost. Future research should explore whether there may be downstream cost savings for the health care system. For example, cost savings may be realized through the observed reductions in nursing home admissions, rehabilitation facility visits, primary care visits and home care visits among SAFE patients. Additionally, the mean time between hospital admission and SAFE referral was over 10 days while the time between referral and SAFE admission was more than 5 days. Expediting this referral and admission process over time has the potential to further reduce days that SAFE patients spend in the hospital and their total cost of care.

Although the number of days spent institution-free was the primary outcome measured, the benefit of transitional care extends beyond this. The results of this study suggest potentially improved care experiences among SAFE patients. First, the provision of transitional care allowed patients to return home for three weeks longer institution-free compared to those who did not receive transitional care. According to a national survey, most Canadian seniors prefer to age at homeCitation55. The provision of transitional care may, therefore, be better aligned with patient preferences. Second, transitional care may have improved the health and health outcomes of patients by mitigating prolonged hospital stays. Patients describe ALC as an isolating and uncertain time, sentiments further echoed by their caregiversCitation33,Citation56–58. SAFE patients spend roughly a third of the time designated as ALC compared to usual care patients. Finally, with respect to health system implications, ALC accounted for 40% of the total length of stay among usual care patients during their index hospitalization. With better transitional care, resources may be used more appropriately towards patients needing acute care while also improving health system flow.

SAFE is not only a cost-effective but also unique model of care. In this study, we demonstrated that a non-hospital, nursing home-based TCU was cost-effective from a public payer’s perspective. We also highlight the possibility of a model of care that leverages existing infrastructure and the available rehabilitative and restorative care resources in nursing homes to support frail, older adults post-hospitalization.

Limitations

The main limitation of our study was the potential inclusion of patients not eligible for SAFE in our usual care group, due to our use of routinely-collected health administrative data to establish a comparison group. The process of admission to the SAFE commences with the screening of ALC patients by a program coordinator. Patients meeting the program’s inclusion criteria, including having rehabilitative potential, are then referred. In doing so, patients most likely to benefit from transitional care are selected. As a result of this process, ALC patients not referred to SAFE may be inherently different from those referred. Specifically, non-selected ALC patients included in the usual care cohort may not have rehabilitative potential and may therefore be less likely to live independently in the community post-discharge, the outcome of interest. We are unable to assess this in health administrative data. However, to minimize possible selection bias, we increased the pool of potential ALC patients to hospitals across the Champlain LHIN (not just ALC patients at the hospital where SAFE patients were admitted in their index event). Usual care patients, therefore, included ALC patients in other area hospitals with SAFE admission potential who were not selected for the program since the service was not available to them. Nonetheless, we were unable to include all eligibility criteria that are used to determine suitability for SAFE in our matching algorithm, as many variables were unavailable in the administrative datasets used. An additional limitation was that this study assumed a preference among patients to return home. Despite prior literature that indicate most older adults have a preference to stay at homeCitation59, this may not reflect the desire of all patients. The calculated measure of effectiveness, which excluded days in institutional care, would therefore be inflated in individuals with a preference for institutionalization. Likewise, the willingness to pay for an institution-free day would, in reality, be lower than that calculated. Lastly, cost effectiveness analyses are sensitive to the study time-horizonCitation60. Due to the limited time-horizon of this study, we were unable to observe healthcare service use beyond six months.

Conclusion

Given the literature on the volume of patients occupying an acute care bed due to insufficient alternative services, the need for transitional care is evident. This study demonstrates that the provision of interdisciplinary nursing and restorative care to older adults, in a program like SAFE, has the potential to improve post-discharge outcomes at a lower cost. Through rehabilitative and restorative care, TCUs can reduce the length of stay in hospitals, increase the potential for independent living, and reduce the risk of subsequent institutionalization. Considering the growing investments into transitional care, this cost-effectiveness research provides a benchmark of the value of nursing home-based transitional care programs with a focus on enhanced function-focused care.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This research was supported by the TOHAMO Innovation Fund of the Alternative Funding Plan for the Academic Health Sciences Centres of Ontario. This study was also supported by ICES, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC). The analyses, conclusions, opinions and statements expressed herein are solely those of the authors and do not reflect those of the funding or data sources; no endorsement is intended or should be inferred.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Author contributions

MM was responsible for the study design, analysis of the data, interpretation of results and writing of the manuscript. DS was responsible for the interpretation of results and provided critical revisions to the manuscript for important intellectual content. ATH was responsible for the study concept and study design and provided critical revisions to the manuscript for important intellectual content. KT was responsible for the study design, interpretation of results and provided critical reviews of the manuscript for its methodological content. AEB was responsible for the analysis and interpretation of data, and for providing critical revisions to the manuscript for its methodological content. AHS was responsible for the study design, and for providing critical revisions to the manuscript for its methodological content. BR was responsible for the inception of this project, provided critical revisions to the manuscript for important intellectual content and was integral to the initial proposal for and the implementation of the SAFE Unit. All authors reviewed the manuscript, gave final approval of the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work. This manuscript has not been submitted or published elsewhere and is not currently under consideration by another journal. The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Peer review disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose. The Deputy Editor in Chief helped with adjudicating the final decision on this paper.

Previous presentation

Poster Presentation at: 2022 Society for Epidemiologic Research (SER) Conference 2022 Conference; 14–17 June 2022; Chicago, United States of America.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (830.6 KB)Acknowledgements

No assistance in the preparation of this article is to be declared.

References

- Turcotte L, Hirdes JP. Long-stay alternate level of care in Ontario complex continuing care beds [Internet]. Waterloo: University of Waterloo School of Public Health and Health Systems; 2015. p. 11. Available from: https://www.oha.com/Documents/Long-Stay%20Alternate%20Level%20of%20Care%20in%20Ontario%20Complex%20Continuing%20Care%20Beds.pdf

- Costa AP, Hirdes JP. Clinical characteristics and service needs of alternate-level-of-care patients waiting for long-term care in Ontario hospitals. Healthc Policy Polit Sante. 2010;6:32–46.

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. Inpatient hospitalization, surgery and newborn statistics, 2019–2020 [Internet]. Ottawa, ON: CIHI; 2021. Available from: https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/dad-hmdb-childbirth-2019-2020-data-table-en.xlsx

- Tsilimingras D, Rosen AK, Berlowitz DR. Patient safety in geriatrics: a call for action. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58(9):M813–819.

- Gillis A, MacDonald B. Deconditioning in the hospitalized elderly. Can Nurse. 2005;101(6):16–20.

- Bhatia D, Peckham A, Abdelhalim R, et al. Alternate level of care and delayed discharge: lessons learned from abroad [Internet]. Toronto, ON: North American Observatory on Health Systems and Policies; 2020. p. 32. Available from: https://ihpme.utoronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/NAO-Rapid-Review-22_EN.pdf

- Quach C, McArthur M, McGeer A, et al. Risk of infection following a visit to the emergency department: a cohort study. Can Med Assoc J. 2012;184(4):E232–E239.

- Baker GR, Norton PG, Flintoft V, et al. The Canadian adverse events study: the incidence of adverse events among hospital patients in Canada. Can Med Assoc J . 2004;170(11):1678–1686.

- Costa AP, Poss JW, Peirce T, et al. Acute care inpatients with long-term delayed-discharge: evidence from a Canadian health region. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:172.

- Sutherland JM, Crump RT. Alternative level of care: Canada’s hospital beds, the evidence and options. Healthc Policy Polit Sante. 2013;9:26–34.

- Weeks LE, Macdonald M, Martin-Misener R, et al. The impact of transitional care programs on health services utilization in community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2018;16(2):345–384.

- Wee S-L, Vrijhoef HJM. A conceptual framework for evaluating the conceptualization, implementation and performance of transitional care programmes. J Eval Clin Pract. 2015;21(2):221–228.

- Eh KX, Han Ang IY, Nurjono M, et al. Conducting a cost-benefit analysis of transitional care programmes: the key challenges and recommendations. Int J Integr Care. 2020;20(1):5–5.

- McGilton KS, Vellani S, Krassikova A, et al. Understanding transitional care programs for older adults who experience delayed discharge: a scoping review. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21(1):210.

- Rehabilitative Care Alliance. Frail seniors guidance on best practice rehabilitative care in the context of COVID-19 [Internet]. 2020. p. 9. Available from: http://rehabcarealliance.ca/uploads/File/Initiatives_and_Toolkits/Frail_Seniors/Frail_Seniors_Guidance_Document.pdf

- Manville M, Klein MC, Bainbridge L. Improved outcomes for elderly patients who received care on a transitional care unit. Can Fam Physician Med Fam Can. 2014;60:e263–e271.

- Barnes DE, Palmer RM, Kresevic DM, et al. Acute care for elders units produced shorter hospital stays at lower cost while maintaining patients’ functional status. Health Aff. 2012;31(6):1227–1236.

- Blewett LA, Johnson K, McCarthy T, et al. Improving geriatric transitional care through inter-professional care teams. J Eval Clin Pract. 2010;16(1):57–63.

- Jayadevappa R, Chhatre S, Weiner M, et al. Health resource utilization and medical care cost of acute care elderly unit patients. Value Health. 2006;9(3):186–192.

- Fox MT, Persaud M, Maimets I, et al. Effectiveness of acute geriatric unit care using acute care for elders components: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(12):2237–2245.

- Counsell SR, Holder CM, Liebenauer LL, et al. Effects of a multicomponent intervention on functional outcomes and process of care in hospitalized older patients: a randomized controlled trial of acute care for elders (ACE) in a community hospital. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(12):1572–1581.

- Landefeld CS, Palmer RM, Kresevic DM, et al. A randomized trial of care in a hospital medical unit especially designed to improve the functional outcomes of acutely ill older patients. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(20):1338–1344.

- Orvik A, Nordhus G, Axelsson S, et al. Interorganizational collaboration in transitional care – a study of a post-discharge programme for elderly patients. Int J Integr Care. 2016;16(2):11.

- Naylor MD, Brooten DA, Campbell RL, et al. Transitional care of older adults hospitalized with heart failure: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(5):675–684.

- Wilson MG. Rapid synthesis: examining the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of rehabilitationcare models for frail seniors [Internet]. Hamilton, ON: McMaster Health Forum; 2013. p. 20. Available from: https://www.mcmasterforum.org/docs/default-source/product-documents/rapid-responses/examining-the-effectiveness-and-cost-effectiveness-of-rehabilitation-care-models-for-frail-seniors.pdf?sfvrsn=0

- Government of Ontario. Ontario adding over 200 more transitional care beds across the province [Internet]. Newsroom; 2020; [cited 2021 Oct 25]. Available from: https://news.ontario.ca/en/release/58823/ontario-adding-over-200-more-transitional-care-beds-across-the-province

- Husereau D, Drummond M, Augustovski F, et al. Consolidated health economic evaluation reporting standards 2022 (CHEERS 2022) statement: updated reporting guidance for health economic evaluations. Health Policy OPEN. 2022;3:100063.

- Boutette M, Hoffer A, Plant J, et al. Establishing an integrated model of subacute care for the frail elderly. Healthc Manage Forum. 2018;31(4):133–136.

- Robert B, Sun AH, Sinden D, et al. A case-control study of the sub-acute care for frail elderly (SAFE) unit on hospital readmission, emergency department visits and continuity of Post-Discharge care. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021;22(3):544–550.e2.

- Mahomed NN, Lau JTC, Lin MKS, et al. Significant variation exists in home care services following total joint arthroplasty. J Rheumatol. 2004;31(5):973–975.

- Armstrong JJ, Zhu M, Hirdes JP, et al. Rehabilitation therapies for older clients of the Ontario home care system: regional variation and client-level predictors of service provision. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37(7):625–631.

- Coyte PC, Young W. Regional variations in the use of home care services in Ontario, 1993/95. Can Med Assoc J. 1999;161:376–380.

- Kuluski K, Im J, McGeown M. “It’s a waiting game” a qualitative study of the experience of carers of patients who require an alternate level of care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):318.

- Challis D, Hughes J, Xie C, et al. An examination of factors influencing delayed discharge of older people from hospital. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;29(2):160–168.

- Afilalo M, Soucy N, Xue X, et al. Characteristics and needs of psychiatric patients with prolonged hospital stay. Can J Psychiatry. 2015;60(4):181–188.

- Bell M, Eriksson LI, Svensson T, et al. Days at home after surgery: an integrated and efficient outcome measure for clinical trials and quality assurance. EClinicalMedicine. 2019;11:18–26.

- Auriemma CL, Taylor SP, Harhay MO, et al. Hospital-Free days: a pragmatic and patient-centered outcome for trials among critically and seriously ill patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;204(8):902–909.

- Cho H, Wendelberger B, Gausche-Hill M, et al. ICU-free days as a more sensitive primary outcome for clinical trials in critically ill pediatric patients. J Am Coll Emerg Phys Open. 2021;2(4):e12479.

- Tomiak M, Berthelot J-M, Guimond E, et al. Factors associated with nursing-home entry for elders in Manitoba, Canada. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55(5):M279–M287.

- Temkin-Greener H, Meiners MR. Transitions in long-term care1. Gerontologist. 1995;35(2):196–206.

- Liu K, Coughlin T, McBride T. Predicting nursing-home admission and length of stay: a duration analysis. Med Care. 1991;29(2):125–141.

- Krumholz HM, Normand S-LT, Wang Y. Trends in hospitalizations and outcomes for acute cardiovascular disease and stroke: 1999–2011. Circulation. 2014;130(12):966–975.

- Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1418–1428.

- Pedersen MK, Meyer G, Uhrenfeldt L. Risk factors for acute care hospital readmission in older persons in Western countries: a systematic review. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2017;15(2):454–485.

- Spector WD, Mutter R, Owens P, et al. Thirty-day, all-cause readmissions for elderly patients who have an injury-related inpatient stay. Med Care. 2012;50(10):863–869.

- CIHI. All-cause readmission to acute care and return to the emergency department [Internet]. Ottawa, Ontario: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2013. p. 64. Available from: https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2013/icis-cihi/H118-93-2012-eng.pdf

- University of Manitoba. Concept: adjusted Clinical Groups® (ACG®) - overview [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2021 Dec 13]. Available from: http://mchp-appserv.cpe.umanitoba.ca/viewConcept.php?printer=Y&conceptID=1304

- Weiner JP, Starfield BH, Steinwachs DM, et al. Development and application of a population-oriented measure of ambulatory care case-mix. Med Care. 1991;29(5):452–472.

- Starfield B, Kinder K. Multimorbidity and its measurement. Health Policy. 2011;103(1):3–8.

- Starfield B, Weiner J, Mumford L, et al. Ambulatory care groups: a categorization of diagnoses for research and management. Health Serv Res. 1991;26(1):53–74.

- Weir S, Aweh G, Clark RE. Case selection for a Medicaid chronic care management program. Health Care Financ Rev. 2008;30(1):61–74.

- Girwar S-AM, Fiocco M, Sutch SP, et al. Assessment of the adjusted clinical groups system in Dutch primary care using electronic health records: a retrospective cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):217.

- Austin PC. A comparison of 12 algorithms for matching on the propensity score. Stat Med. 2014;33(6):1057–1069.

- Stuart EA, Lee BK, Leacy FP. Prognostic score–based balance measures for propensity score methods in comparative effectiveness research. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(8 Suppl):S84.e1–S90.e1.

- March of Dimes Canada. National survey shows Canadians overwhelmingly want to age at home; just one-quarter of seniors expect to do so [Internet]. News Room; 2021 [cited 2021 Nov 15]. Available from: https://www.marchofdimes.ca/en-ca/aboutus/newsroom/pr/Pages/Aging-at-Home.aspx

- Swinkels A, Mitchell T. Delayed transfer from hospital to community settings: the older person’s perspective. Health Soc Care Community. 2009;17(1):45–53.

- Cressman G, Ploeg J, Kirkpatrick H, et al. Uncertainty and alternate level of care: a narrative study of the older patient and family caregiver experience. Can J Nurs Res. 2013;45(4):12–29.

- Kydd A. The patient experience of being a delayed discharge. J Nurs Manag. 2008;16(2):121–126.

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. Health care in Canada, 2011: a focus on seniors and aging [Internet]. Ottawa, ON: CIHI; 2011. Available from: https://www.homecareontario.ca/docs/default-source/publications-mo/hcic_2011_seniors_report_en.pdf

- Cohen DJ, Reynolds MR. Interpreting the results of cost-effectiveness studies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(25):2119–2126.