Abstract

Aims

Schizophrenia has the highest median societal cost per patient of all mental disorders. This review summarizes the different costs/cost drivers (cost components) associated with schizophrenia in 10 countries, including all cost types and stakeholder perspectives, and highlights aspects of disease associated with greatest costs.

Materials and methods

Targeted literature review based on a search of published research from 2006 to 2021 in the United States (US), United Kingdom (UK), France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Canada, Japan, Brazil, and China.

Results

Sixty-four published articles (primary studies and literature reviews) were included. Comprehensive data were available on costs in schizophrenia overall, with very limited data for individual countries except the US. Most data is related to direct and not indirect costs, with extremely scarce data for several key cost components (adverse events, suicide, long-term care). Total schizophrenia-related per person per year (PPPY) costs were $2,004–94,229, with considerable variability among countries. Indirect costs were the main cost driver (50–90% of all costs), ranging from $1,852 to $62,431 PPPY. However, indirect costs are not collected systematically or incorporated in health technology assessments. Total schizophrenia-related PPPY direct costs were $4,394–31,798, with inpatient cost as the main cost driver (∼20–99% of direct costs). Intangible costs were not reported. Despite limited evidence, total schizophrenia-related costs were higher in patients with than without negative symptoms, largely due to increased costs of medication and medical visits.

Limitations

As this was not a systematic review, prioritization of studies may have resulted in exclusion of potentially relevant data. All costs were converted to USD but not corrected for inflation or subjected to a gross domestic product deflator.

Conclusions

Direct costs are most commonly reported in schizophrenia. The substantial underreporting of indirect and intangible costs undervalues the true economic burden of schizophrenia from a payer, patient, and societal perspective.

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY

The true costs of diseases such as schizophrenia extend far beyond the obvious direct costs of hospital visits, outpatient appointments and medications to include indirect costs such as loss of productivity among patients and caregivers due to unemployment, early retirement and premature death. This review of literature published between 2006 and 2021 reveals that the indirect costs of schizophrenia actually account for between 50% and 90% of all costs, but are often not taken into account in healthcare planning. In addition, intangible costs, including the pain, suffering, stress, and anxiety experienced by patients and caregivers due to schizophrenia have not been reported in the literature. Costs were also higher for patients with negative symptoms of schizophrenia (where patients appear withdrawn and lacking in emotion, with few social relationships) compared with those with positive symptoms (including delusions or hallucinations). This is largely due to the greater costs for medications and medical visits among patients with negative symptoms. In summary, this review demonstrates that the true cost of schizophrenia, including direct, indirect, and intangible costs, is likely to be substantially higher than the values for the cost of disease currently reported.

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a complex mental disorder, characterized by a combination of positive symptoms (e.g. hallucinations, delusions, disorganized thoughts or speech, and bizarre behaviors), negative symptoms (lack of motivation, drive, enjoyment, social interactions), cognitive dysfunction (affecting attention, memory, executive functioning, social interactions), and motor disturbances that can lead to functional impairment and poor health-related quality of lifeCitation1,Citation2. Schizophrenia typically presents in late adolescence to early adulthood, with peak prevalence around 40 years of ageCitation1,Citation3. Schizophrenia develops gradually, with positive symptoms diminishing over time while negative symptoms persistCitation3,Citation4.

Although schizophrenia is a chronic, long-term conditionCitation5, treatment with pharmaceutical therapies in combination with psychotherapeutic interventions is recommended for the management of psychosis and exacerbations, and for the prevention of relapseCitation6–8. However, the antipsychotic medications currently available predominantly target positive symptoms via a process of dopamine modulation. This creates an important unmet need, as a substantial number of patients continue to experience negative and cognitive symptomsCitation9.

Although the reported prevalence of schizophrenia is relatively low (global age-standardized prevalence was reported to be 0.28% in 2016Citation1) there is some evidence to suggest that symptoms may be underreported, partly due to the stigma associated with the condition, and also due to the high specificity but low sensitivity of community-surveying components of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI)Citation10,Citation11. The burden of schizophrenia is known to be substantialCitation1,Citation3, with impacts including mortality, psychiatric comorbidities such as substance abuse and depression, poor social functioning, and unemploymentCitation12.

A systematic literature review conducted to characterize costs of mental disorders reported that schizophrenia was associated with the highest median societal cost per patient worldwide, at 13,256 United States Dollars [USD] (adjusted according to purchasing power parity [PPP]) compared with 10,105 USD PPP for intellectual disabilities, 5,834 USD PPP for personality disorders, 4,681 USD PPP for substance use and 4,492 USD PPP for mood disordersCitation13. Healthcare costs of Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia have been reported to be twice as high compared with patients without schizophrenia ($28,644 vs. $14,557; p < .01), largely due to the increased costs of long-term care (incremental cost increase of $4,677), inpatient stays ($2,044), time spent in mental health institutes ($1,990), and pharmacy costs ($1,836) (p < .001 in all cases)Citation14. Similar increases in cost for patients with schizophrenia have also been reported among privately insured patients in the United States (US)Citation15.

Although cost of illness data are available for schizophrenia, methods used for the collection and reporting of costs are disparate, as well as lack an overarching framework or classification. The objectives of this manuscript therefore were to (1) Describe published evidence to date concerning the spectrum of types of costs in schizophrenia; (2) Identify and summarize published evidence on schizophrenia cost of illness in the US, United Kingdom (UK), France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Canada, Japan, Brazil, and China; (3) Identify and describe key cost drivers for schizophrenia from the perspective of different stakeholders (patient/caregiver/family member, healthcare system, society). In this context, the term ‘cost drivers’ refers to those components (cost types) that predominantly contribute to the total cost of schizophrenia. For the purposes of this review, only cost components were considered as cost drivers, with other cost factors associated with increased or decreased cost falling outside the scope of this review. In addition, a detailed exploration into reasons for the differences in costs among the included countries was also outside the scope of this review.

This targeted literature review provides a comprehensive overview of the different costs and cost drivers associated with schizophrenia in 10 countries, including all types of costs and all stakeholder perspectives. It also highlights the aspects of the disease that are associated with the greatest costs. Given the vast amount of published literature on this topic, and the existing availability of some comprehensive systematic literature reviews, this review did not aim to summarize all literature in this area. Instead, a pragmatic, targeted approach was adopted to provide focus to the review and avoid dilution of findings through an excess of data. This approach has previously been used in many published reviews of economic burdenCitation16–20.

Methods

Search strategy

As a first step in this project, an initial scoping review was carried out, which informed the decision to proceed with a targeted review and also helped to identify countries of interest. As part of the scoping review, structured searches were conducted in Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (MEDLINE; National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, MD) via Embase.com and in Excerpta Medica Database (Embase; Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) via Embase.com, using the search facet for disease (schizophrenia) and objectives of interest (economic burden). This approach identified >10,000 hits for screening. The top 250 hits were screened on the basis of the abstract, and the likely inclusion rate was found to be high, with >250–300 relevant studies anticipated. Due to the substantial expected volume of data, it was agreed to conduct a targeted review and focus on strategic geographies and other key aspects.

Following the scoping review, relevant publications were identified using MEDLINE via Embase.com and Embase. In addition, Google and Google Scholar were used to identify relevant publications. Each search was conducted using controlled vocabulary and key words. The publication timeframe was 2006–2021, although additional references dating back to 1994 were also included from back referencing of SLRs.

Selection criteria

Titles and abstracts (ti/ab) of articles identified were carefully screened by a single reviewer in the initial review for relevance to the topic. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for study selection are summarized in . In order to include a broad geographic scope and represent diverse healthcare systems, it was decided that the review would include studies conducted in the US, five European countries (UK, France, Germany, Italy, and Spain), Canada, Japan, Brazil, or China. Studies published in the English language only were included.

Table 1. Inclusion/exclusion criteria for study selection.

Articles identified as potentially relevant were obtained in full text for further evaluation. Every full-text article was screened by a single reviewer.

Prioritization

This review focused on key publications that adequately addressed the objectives of the research and fulfilled specific selection criteria such as adequacy of sample size, representativeness of data across key countries of interest, recentness of data, and coverage of multiple research questions. In particular, the original studies that were included were complementary to the published systematic literature reviews, providing an update to the evidence. The selection of data sources for extraction and reporting was done by two independent reviewers. Given the descriptive nature of this targeted review, relevant data were narratively synthesized and reviewed by all authors.

Currency reporting

Costs are reported in the currency of the country where the study was conducted, as reported in the original publication. To aid comparison among countries, currency-specific costs were also converted to USD using the exchange rate specific to the year of data collection, or the date of the original publication if the specific year was not specified.

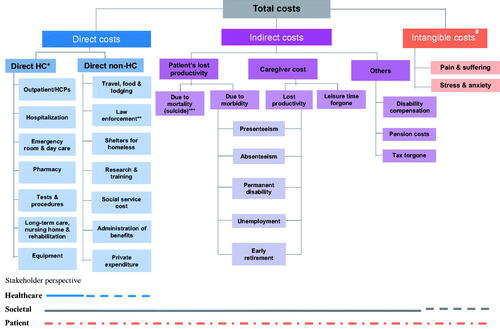

Classification of costs

Costs due to schizophrenia can broadly be divided into direct, indirect & intangible costs. Direct costs correspond to the costs of caring for the patient, and can be separated into direct medical costs and direct non-medical costs. Indirect costs correspond to productivity losses among patients and caregivers, including impact on paid activities as well as value to society, including voluntary work and household or familial duties. In schizophrenia specifically, indirect costs tend to include excess morbidity and premature mortality arising from comorbidities including cardio-metabolic and respiratory disorders. Intangible costs impact both patient and caregivers, and are a conceptual measure of the cost of pain and sufferingCitation21. All costs can be viewed from several perspectives, beginning with the patient, followed by the payer, the healthcare system, and finally society in general. Other potential perspectives are not considered in detail in this review. As described below, there may be some overlap between the perspectives of the different stakeholders.

The patient perspective focuses on the impact of disease on patients and family in managing the disease and its consequences. It can include co-payments or out-of-pocket expenditures, which can be directly related to care or expenditure required to adapt to the diseaseCitation21. The payer perspective includes costs covered and reimbursed by the payer and is affected by the specifics of individual healthcare systems. The payer perspective may be limited to direct costs only or may also include indirect costs when the payer is also responsible for daily allowance or disability pension. The perspective of the healthcare system may be broader than that of the payer, as the payer perspective depends on the limits of their financial and management responsibility. The societal perspective is the most comprehensive and includes all aspects that are important to society and its functioning, and takes into account both direct and indirect costs. As specific stakeholders have an interest in different costs and outcomes, the outcomes of studies tend to differ depending on the perspective of the stakeholderCitation22–24.

Results

Summary of included studies

Following the initial searches, 126 full-text publications were screened, with 64 articles selected for final inclusion in this review. The characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Supplementary Table 1.

Of the 64 publications included in this review, 47 were primary studies and 17 were literature reviews. Approximately 65% (n = 42) of the citations were published in the last 6 years. The majority of the 47 primary studies (∼85%; n = 39) were retrospective cohort studies. Approximately 75% (n = 34) of the studies had a sample size of greater than 1,000. Approximately 55% (n = 25) of the studies were conducted in North America (US, or Canada) and ∼25% (n = 13) were conducted in Europe (UK, France, Germany, Italy, or Spain), with four studies conducted in Japan, three in China, and two in Brazil.

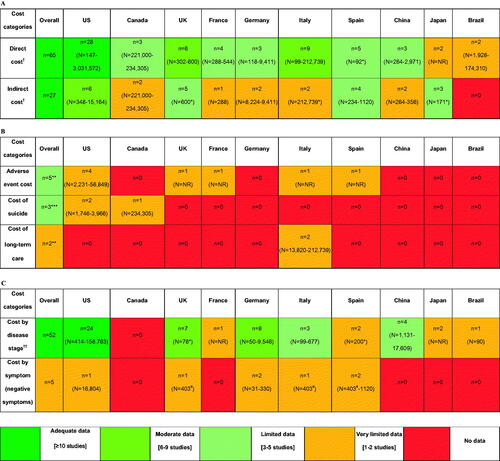

Based on the included 64 publications, comprehensive data were available on costs in schizophrenia taken as a whole (). However, on a country-level, data were limited or very limited for most of the countries except the US. In addition, most of the data available related to direct costs rather than indirect costs, with indirect cost data from Brazil in particular being poorly represented. For several key cost components of interest (adverse events [AEs], suicide and long-term care), there were extremely scarce data, coming from a limited number of studies. Costs by disease stage were generally better represented in the data than costs by symptomology (negative symptoms), with very limited or no data in all countries for the latter category.

Figure 1. Distribution of publications based on (a) Cost type (direct vs indirect); (b) Key cost components of interest; (c) Key drivers of cost (disease stage and negative symptoms). †Cost for all schizophrenia population (disease stage and/symptom profile not specified). *Sample size reported in one study only & not reported in other studies. **All studies reported direct costs. ***Two studies reported direct cost and one reported indirect costs for suicide ††Costs by specific stage of schizophrenia (e.g., relapsed, stable/chronic etc.) – all studies reported direct costs except one study from Japan which reported indirect cost. #The EPSILON study (Knapp 2002)Citation42 reports combined costs for the five European countries for two groups: patients with negative symptoms (N = 250) vs. w/o negative symptoms (N = 153) including UK (N = 84; patients with negative symptoms = 50), Spain (N = 100; patients with negative symptoms = 69), Italy (N = 107; patients with negative symptoms = 52), The Netherlands and Denmark. Abbreviations. n, number of studies reporting data for given cost category and country; N, sample size; NR, not reported; SCZ, schizophrenia; UK, United Kingdom; US, United States.

Overall costs

A schematic to represent the broad spectrum of cost components contributing to the overall schizophrenia-related economic burden has been devised based on the cost components reported in individual studies and described in this review ().

Figure 2. Characterization of the economic burden of schizophrenia. Schematic devised based on cost components presented in individual publications included in this review. *Includes costs of adverse events. **Incarceration, judicial & legal services, police protection; some studies consider these components under indirect costs. ***Some studies consider suicide under direct costs. #Includes costs for both patients and caregivers. Abbreviations. HC, healthcare; HCP, healthcare professional.

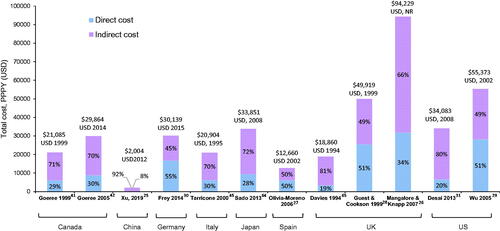

The total schizophrenia-related per patient per year (PPPY) cost varied from $2,004Citation25 to $94,229Citation26 in the assessed countries (). PPPY total costs were not reported for Brazil and France. Indirect costs were the main cost driver of total costs, ranging from ∼50%Citation27–29 to ∼90%Citation25 of total costs across all countries except Germany, where indirect costs accounted for 45% of total costsCitation30.

Figure 3. Total per patient per year costs of schizophrenia across countries. All costs quoted in the original publications were converted to USD using the exchange rate for the particular years of data collection, or for the year of publication if the data collection period was not specified. However, no GDP deflator was used, and costs were not corrected for inflation. All studies providing data on total costs from our prioritized data set are included. Abbreviations. GDP, gross domestic product; NR, not reported; PPPY, per patient per year; UK, United Kingdom; US, United States; USD, United States Dollar.

Direct costs

Overall direct costs

Overall, inpatient costs were the main cost driver for direct costs, contributing ∼20–99% of direct costs across all countries.

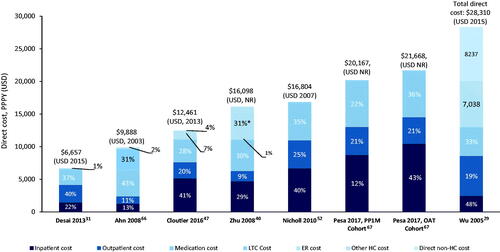

In the US, the total schizophrenia-related PPPY direct costs varied from $6,657Citation31 to $28,310Citation29 (). No consistent cost driver for direct cost was observed across studies (inpatient cost was the main driver in four studies, medication costs in two studies and outpatient costs in one study). Only one studyCitation29 included direct non-healthcare costs, consisting of costs for sheltered homes and legal costs.

Figure 4. Total PPPY direct costs ($) in the US. Costs were not corrected for inflation. *Other HC costs included psychosocial group therapy, medication management, individual therapy and case management. Abbreviations. ER, emergency room; HC, healthcare; LTC, long-term care; NR, not reported; PPPY, per patient per year; US, United States of America; USD, United States Dollar.

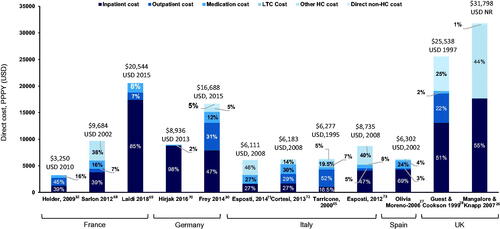

Across European countries (UK, France, Germany, Italy, and Spain), the total schizophrenia-related PPPY direct costs varied from $3,250 in FranceCitation32 to $31,798 in the UKCitation26 (). Inpatient costs were the main cost driver in the majority (∼70%) of the studies, contributing to ∼40–85% of the total direct costs. Only three studies included direct non-healthcare costs, with substantial variations in the type of non-healthcare costs including costs for sheltered homes and legal cost in the UKCitation28, legal costs and administration of benefits in the UKCitation26, and administration of benefits and transport costs in GermanyCitation30.

Figure 5. Total PPPY direct costs ($) across five European countries (France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and UK). All costs quoted in the original publications were converted to USD using the exchange rate for the particular years of data collection, or for the year of publication if the data collection period was not specified. However, no GDP deflator was used, and costs were not corrected for inflation. Abbreviations. ER, emergency room; GDP, gross domestic product; HC, healthcare; LTC, long-term care; NR, not reported; PPPY, per patient per year; US, United States of America; USD, United States Dollar.

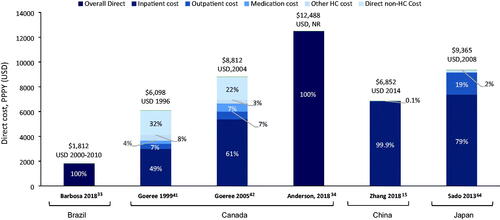

Across the remaining countries, the total schizophrenia-related PPPY direct costs varied from $1,812 in BrazilCitation33 to $12,488 in CanadaCitation34 (). Overall, inpatient costs were the main cost driver, contributing ∼50–99% of direct costs across Canada, China and Japan. Only two studies included direct non-healthcare costs (both from Canada), which included sheltered home costs, legal costs, administration of benefits.

Figure 6. Total PPPY direct costs ($) across other countries (Brazil, Canada, China, and Japan). All costs quoted in the original publications were converted to USD using the exchange rate for the particular years of data collection, or for the year of publication if the data collection period was not specified. However, no GDP deflator was used, and costs were not corrected for inflation. Abbreviations. ER, emergency room; GDP, gross domestic product; HC, healthcare; LTC, long-term care; NR, not reported; PPPY, per patient per year; US, United States of America; USD, United States Dollar.

Adverse events (AEs) costs

Overall, there were limited data on AE costs in schizophrenia. The total PPPY direct healthcare costs were higher in schizophrenia patients with incident cardiometabolic AEs due to antipsychotics than those without such AEs (US data reported only)Citation35. Over the 3-year study period, schizophrenia patients with incident cardiometabolic AEs incurred increases of $1,460 in mean psychiatric medication and visit costs/year (p = .0001), $266 in mean medical medication and visit costs/year (p < .0001), and $1,249 in mean total medication and visit costs (p = .003) compared with those without one of these conditions.

In Europe, among cardiometabolic events due to antipsychotics, the direct medical PPPY costs were generally higher for cardiovascular and metabolic events (diabetes, weight gain, hyperprolactinemia, QT prolongation) than other AEsCitation36 (). Schizophrenia-related PPPY direct costs were also higher in patients with extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) due to atypical antipsychotics compared with those without EPS ($18,682 vs $17,214, respectivelyCitation37 and $25,911 vs $21,500, respectivelyCitation38 for all-cause direct healthcare costs; and $9,377 vs $6,249, respectivelyCitation37 and $12,134 vs $6,230, respectivelyCitation38 for schizophrenia-specific direct healthcare costs) (US data reported only).

Table 2. Country-specific costs for management of AEs among schizophrenia patients in four European countries.

Other direct costs

Schizophrenia-specific criminal justice system costs accounted for ∼3% of the total direct costs in the USCitation39,Citation40 and 6% in CanadaCitation41. The costs of residential facilities accounted for 16.8% of the total direct costs of schizophrenia in CanadaCitation42 and 49% in ItalyCitation43.

Indirect costs

Overall indirect costs

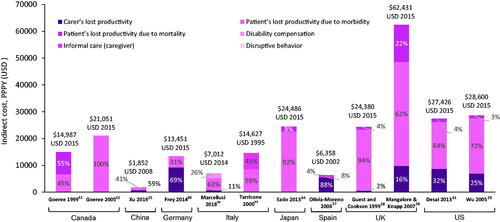

Indirect PPPY costs of schizophrenia ranged from $1,852Citation25 to $62,431Citation26 in the assessed countries (). Patient’s loss of productivity due to morbidity was the main cost driver (∼45–100% of indirect costs) across all countries except Germany and Spain where carer’s loss of productivity was the main cost driver (∼70%Citation30 to 88%Citation27.

Figure 7. Indirect per patient per year costs of schizophrenia across countries. All costs quoted in the original publications were converted to USD using the exchange rate for the particular years of data collection, or for the year of publication if the data collection period was not specified. However, no GDP deflator was used, and costs were not corrected for inflation. All studies providing data on total costs from our prioritized data set are included. PPPY indirect cost data reported for France and Brazil in the selected publications. Abbreviations. FCA, friction cost approach; GDP, gross domestic product; HCA, human capital approach; NR, not reported; PPPY, per patient per year; UK, United Kingdom; US, United States; USD, United States Dollar.

Other indirect costs

Schizophrenia-specific annual family impact costs were reported in one reviewCitation44 and accounted for 2.3% of the indirect costs in the UKCitation28, 17% in the USCitation39, ∼40% in ItalyCitation45, and 69–85% in SpainCitation46. The most common impacts on families were constraints on social activities, negative effects on family life, and feelings of loss, which might also be considered as components of intangible costs. Patients living in a family environment might impose additional costs through household expenditure, travel costs, or lost earnings for those who care for them.

Three studies reported the costs of suicide; one of which reported this as an indirect cost while two reported suicide as a direct cost of schizophrenia. According to these studies, the cost of premature mortality (suicide) accounted for 2.8% of the total indirect costs in the US ($3,307 million in total)Citation47, while the costs of suicide and attempted suicide (not including hospitalization) accounted for 0.3% of the total national direct costs of schizophrenia in Canada (CAN$6 million)Citation42.

Intangible costs

No data reporting on intangible costs for schizophrenia were identified.

Disease-related costs

Costs by patient symptomatology

Overall, there were very limited data on costs by patient symptomatology in schizophrenia. The available limited data suggest that total schizophrenia-related costs are higher in patients with negative symptoms than those without negative symptoms. In the US, the estimated mean annual inpatient cost of care for patients with negative symptoms of schizophrenia (NSS) ($45,410, SD=$26,768) was significantly higher than for patients with non-negative symptoms of schizophrenia (NNSS; $33,049, SD=$16,656; p < .001). Similarly, the estimated mean annual total cost of care for NSS patients ($55,864, SD=$68,298) was significantly higher than for NNSS patients ($43,385, SD=$40,068; p < .001)Citation48. In Spain, the total schizophrenia-related PPPY cost was higher in patients with negative symptoms (€2,170) than those without negative symptoms (€1,765), largely due to increased costs of medication (€1,019 vs €782), medical visits (€385 vs €323), and specialized medical visits (€273 vs €223)Citation49.

In the EPSILON study conducted in the UK, Spain, Italy, Denmark, and the Netherlands in 1998, the total direct PPPY cost was £5,966 for patients with negative symptoms compared with £3,555 for those without negative symptomsCitation50. Each unit increase in the negative symptom score (measured using Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale) was associated with increased inpatient costs of £1,950; equivalent to 10 days, which is of clinical and economic significance. Mean annual costs were 48–180% higher for patients with negative symptoms in all categories, except for outpatient care which were 42% lower for patients with negative symptoms (PPPY costs of inpatient care [£3,340 vs £1,986], outpatient care [£223 vs £386], day care [£1,334 vs 618], community services [£573 vs £387] and residential services [£496 vs £177]). The authors postulated that patients not experiencing acute positive symptoms might be considered relatively stable; therefore, the need for outpatient care might be under-recognized in these patients resulting in decreased outpatient costs.

In another study conducted in the mid-90s in GermanyCitation51, the total direct costs of schizophrenia were moderately correlated with negative symptoms (p < .05), but not with positive or general symptoms, however no separate cost data were reported for patients with and without negative symptoms.

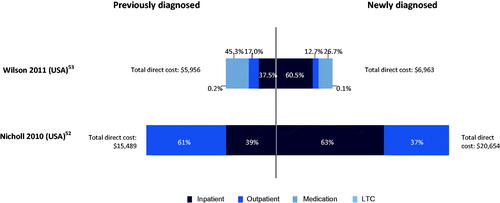

Costs by disease stage

The total schizophrenia-related PPPY direct cost was higher among newly diagnosed patients than among those with previously diagnosed chronic diseaseCitation15,Citation52,Citation53 (). In newly diagnosed patients, the higher hospitalization and emergency room use was due to widespread substance abuse and/or treatment adherence issues. In addition, there was less likelihood of seeking outpatient care necessary for appropriate disease management and relapse prevention. In previously diagnosed patients, lower inpatient costs were due to more complex medication regimes (higher medication costs are driven by greater use of costly atypical antipsychotics, including clozapine and olanzapine).

Figure 8. Total PPPY direct cost ($) for previously diagnosed vs newly diagnosed patients. Abbreviations. LTC, long-term care; PPPY, per patient per year; US, United States; USD, United States Dollar.

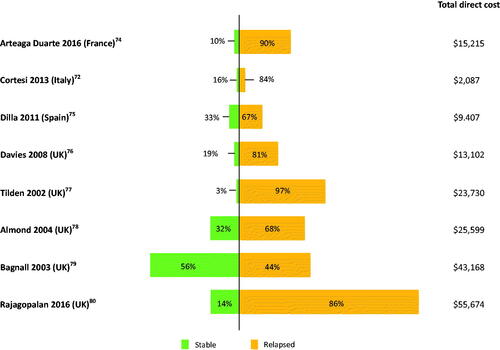

Total schizophrenia-related PPPY direct cost was higher among patients with relapsed schizophrenia compared with stable schizophreniaCitation36 (). The most common measure of relapse was hospitalization due to exacerbation of symptoms. The costs of relapse were a weighted average of the costs of relapses requiring and not requiring hospitalizations, using country-specific weights where available. Schizophrenia patients with relapse had 56–1,100%-higher total direct costs than those without a relapse in one systematic literature review (SLR)Citation54. Higher costs for relapsed patients were likely due to higher hospitalization rates and inpatient days, higher psychiatric outpatient visits, and more severe disease, treatment resistance. Most studies were limited to a healthcare perspective using clinical or administrative data; hence, there is limited evidence of the impact of relapse on social care costs. The only available data from China indicate that additional indirect costs of morbidity, mortality and criminal damage related to relapse are modest.

Figure 9. Total PPPY direct cost ($) for patients with relapsed schizophrenia vs stable schizophrenia. All costs quoted in the original publications were converted to USD using the exchange rate for the particular years of data collection, or for the year of publication if the data collection period was not specified. However, no GDP deflator was used, and costs were not corrected for inflation. Abbreviations. GDP, gross domestic product; PPPY, per patient per year; UK, United Kingdom; USD, United States Dollar.

Costs for non-remitted patients were significantly higher than those for remitting patients in every category except for inpatient costsCitation55. Indeed, for every 6-month period following baseline, costs associated with non-remitted patients were between $1,200 and $2,800 higher than those for non-remitted patients. As adherence to medication was lower among non-remitted patients, some of the increased costs could be due to increased numbers of relapses due to poor adherence. These findings indicate the need for more effective treatments that allow patients to achieve remission, thus reducing the costs of schizophrenia for healthcare systems.

Discussion

The objectives of this review were to identify and describe the different types of costs contributing to the overall cost of schizophrenia from a societal perspective. Our intention was also to highlight key cost drivers (components that predominantly contribute to the total cost of schizophrenia), existing evidence gaps, and those contributing costs that are not commonly collected or reported, including productivity losses and intangible costs.

The costs of schizophrenia can be evaluated from the perspective of the healthcare system, patients (including caregivers and family members), or society. Most studies report direct rather than indirect costs, showing a gap in the literature regarding the perspective of patients, their families and caregivers. However, results of this review reveal that indirect costs are actually more prominent than direct costs, contributing between 50% and up to 90% of total costs of schizophrenia across most countries. Patient loss of productivity due to morbidity and carer’s loss of productivity were the main driver of indirect costs. Considerably fewer studies reported on indirect costs compared with direct costs, suggesting that societal costs are not well quantified, and are likely to be underestimated.

In terms of disease stage, total schizophrenia-related PPPY direct costs were higher among newly diagnosed patients versus previously diagnosed patients, relapsed versus stable patients, and non-remitting versus remitting patients.

Our study also revealed considerable variation between countries in most cost measures. Although it was not an objective of this study to evaluate reasons for between-country differences in costs, we suggest that the divergences may be due to differences in the underlying study population that are inevitable when independent studies are compared. Most notable reasons for the cost differences may include study methodology (study design, data source used, methodologies used to recruit patients), time frame for data collection, cost components, methods of estimating costs, and differences in healthcare systems. Even within the same country, variations in reported costs could be due to differences in study methodology. For example, the heterogeneity in indirect costs was related to the type of productivity loss included (as only a few studies included carer’s lost productivity or patient lost productivity due to mortality, excluding these components may have led to underestimation of the indirect costs). In addition, variations in the methods used for estimating productivity losses (human capital approach [HCA] vs friction cost approach [FCA]) may explain some of the variation, as productivity losses estimated by the HCA were found to be nearly 70-times those estimated using the FCA.

In addition, many western countries have initiated a ‘deinstitutionalization’ process over recent decades, by transferring chronic treatment for the mentally ill from psychiatric hospitals to the community, potentially leading to increased risk of violent crime in these patients. This could explain why legal costs (direct non-healthcare cost) have been more commonly reported in studies conducted in western countries (Canada, US & Europe) than in countries such as Japan, in which few attempts at deinstitutionalization have been madeCitation56.

The limited data available on costs by predominant patient symptomatology suggest that total schizophrenia-related costs are higher in patients with negative symptoms than in those without negative symptoms. Up to 60% of schizophrenia patients have prominent or predominant negative symptoms that are clinically relevant and need treatmentCitation57,Citation58. Negative symptoms are associated with long-term morbidity and poor functional outcomesCitation59,Citation60, especially in areas such as impaired occupational and academic performance, household integration, social functioning, participation in activities, and quality of lifeCitation61. Antipsychotic medications, which are considered the standard of care in schizophrenia are effective for the treatment of positive symptoms, but have limited efficacy for treating negative symptomsCitation62. Negative symptoms therefore remain an unmet medical need in schizophrenia, which has led to an increased focus on the assessment and management of negative symptomsCitation59. Quantifying the costs associated with negative symptoms would therefore be useful to understand the monetary value of new treatments for negative symptomsCitation63.

This review also reveals several important evidence gaps in the published literature. For example, with the exception of the US, data on direct and indirect costs were confined to very limited data for most countries (although there were adequate data from the UK and Italy for direct costs). Overall, there were also very limited data for key cost components such as AEs, suicides, and long-term care/institutionalization. No data were identified on intangible costs including pain and suffering and stress and anxiety, despite the fact that intangible costs clearly contribute to the broader schizophrenia burden. Finally, there were very limited data on how costs vary by predominant patient symptomatology, particularly in patients with negative symptoms, with most of the available data being relatively older, limiting their applicability.

Limitations

There are a number of limitations of this research which should be acknowledged. One limitation could be the decision to conduct a targeted literature review, rather than a SLR. However, the methodology adopted in this review was robust and thorough, and was guided by similar principles to an SLR, including the a priori definition of clear objectives and the use of two independent reviewers to perform the selection of publications for extraction and reporting. While we acknowledge that prioritization of studies during selection may have resulted in the exclusion of potentially relevant data, we are confident that the most reliable studies were selected for detailed analysis following an initial scoping review, and it is therefore not expected that the conclusions of this review will be substantially impacted by the excluded literature.

All costs quoted in the original publications were converted to USD using the exchange rate for the particular years of data collection, or for the year of publication if the data collection period was not specified. However, no gross domestic product (GDP) deflator was used, and costs were not corrected for inflation. This means that an absolute comparison of costs between studies published at different timepoints is not strictly possible.

Most of the studies included in this review were retrospective cohort studies, reflecting the methodology most frequently used in published studies in this area. This opens the possibility of confounding by indication, which may have hindered accurate comparison across medications. However, as the review considered overall costs rather than costs of individual treatments, we believe that any effect on the study conclusions will be relatively small.

Another limitation is that due to a paucity of published data regarding costs by symptomology, we were not able to analyze costs by symptoms such as cognitive symptoms and were only able to comment on costs according to the presence of negative or positive symptoms.

Finally, cost-effectiveness and cost-utility analyses were listed as exclusions in the review protocol, meaning that some estimated cost data may not have been captured in this review.

Recommendations for future costs studies

To achieve a more comprehensive understanding of the economic burden of schizophrenia, further research is required. Most importantly, more consistent, comprehensive and comparable cost collection and reporting is required in future research studies, potentially using the overarching classification framework proposed in this study (). In order to explore more fully the reasons for the differences in costs noted between countries, future research should focus on the impact of differences in health and social care systems, as well as differences in the services and treatments offered, country-specific guideline recommendations, and local adherence to treatment guidelines. Prospective research should also aim to capture data from countries with developing economies, particularly with regard to indirect costs. Finally, further quantification of the cost impact of negative symptoms would be valuable as well as some quantification of intangible costs.

Conclusions

Total schizophrenia-related PPPY cost varied from $2,004 to $94,229 in the assessed countries, with indirect cost as the main cost driver (∼50–90% across all countries). Considerable variability was seen in costs across countries mainly due to differences in the underlying study population, time frame for data collection, cost components, methods of estimating costs, and differences in healthcare systems. Indirect costs are important cost drivers, but are not collected systematically or taken into account in health technology assessments. Despite the limited evidence available, negative symptoms appear to be associated with significant economic burden in schizophrenia.

Transparency

Author contributions

AK, DM and SD were involved in the conception and design of this study, as well as the analysis and interpretation of the data. AK, DM, SD, DJ and KS were involved in drafting the paper and revising it critically for intellectual content, as well as the final approval of the version to be published.

All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All authors agree with the presented findings, and agree that the work has not been published before nor is being considered for publication in another journal.

Reviewer disclosures

A reviewer on this manuscript has disclosed that they have received manuscript or speaker’s fees from Astellas, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Elsevier Japan, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Kyowa Yakuhin, Lundbeck Japan, Meiji Seika Pharma, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, MSD, Nihon Medi-Physics, Novartis, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Shionogi, Shire, Sumitomo Pharma, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Tsumura, Viatris, Wiley Japan, and Yoshitomi Yakuhin, and research grants from Eisai, Mochida Pharmaceutical, Meiji Seika Pharma, Shionogi and Sumitomo Pharma. The other peer reviewers on this manuscript have no other relevant financial relationships or otherwise to disclose.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (109.4 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge and thank Rachel Danks (Bridge Medical Consulting) for her editorial support and Shailesh Advani (Bridge Medical Consulting) for assistance in data analysis.

Declaration of funding

This work was supported by F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

AK and KS are employees and shareholders at F. Hoffmann- La Roche. DJ is an employee and a shareholder at Roche Products Ltd. DM and SD are employees of Bridge Medical Consulting, which was contracted by F. Hoffmann-La Roche to conduct this research.

References

- Charlson FJ, Ferrari AJ, Santomauro DF, et al. Global epidemiology and burden of schizophrenia: findings from the global burden of disease study 2016. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44(6):1195–1203.

- Kahn RS, Sommer IE, Murray RM, et al. Schizophrenia. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015;1:15067.

- Javitt DC. Balancing therapeutic safety and efficacy to improve clinical and economic outcomes in schizophrenia: a clinical overview. Am J Manag Care. 2014;20(8 Suppl):S160–S5.

- McCutcheon RA, Reis Marques T, Howes OD. Schizophrenia-an overview. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(2):201–210.

- Insel TR, Scolnick EM. Cure therapeutics and strategic prevention: raising the bar for mental health research. Mol Psychiatry. 2006;11(1):11–17.

- Grover S, Chakrabarti S, Kulhara P, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for management of schizophrenia. Indian J Psychiatry. 2017;59(Suppl 1):S19–S33.

- Keepers, et al. The American psychiatric association practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177:868–872.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: prevention and management. Clinical guideline [CG178]. 2014. [cited 2022 Jul]. Available from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg178.

- Krogmann A, Peters L, von Hardenberg L, et al. Keeping up with the therapeutic advances in schizophrenia: a review of novel and emerging pharmacological entities. CNS Spectr. 2019;24(S1):38–69.

- Cho SJ, Kim J, Kang YJ, et al. Annual prevalence and incidence of schizophrenia and similar psychotic disorders in the Republic Of Korea: a national health insurance data-based study. Psychiatry Investig. 2020;17(1):61–70.

- Cooper L, Peters L, Andrews G. Validity of the composite international diagnostic interview (CIDI) psychosis module in a psychiatric setting. J Psychiatr Res. 1998;32(6):361–368.

- Crespo-Facorro B, Such P, Nylander AG, et al. The burden of disease in early schizophrenia – a systematic literature review. Curr Med Res Opin. 2021;37(1):109–121.

- Christensen MK, Lim CCW, Saha S, et al. The cost of mental disorders: a systematic review. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2020;29:e161.

- Pilon D, Patel C, Lafeuille MH, et al. Prevalence, incidence and economic burden of schizophrenia among medicaid beneficiaries. Curr Med Res Opin. 2021;37(10):1811–1819.

- Zhang W, Amos TB, Gutkin SW, et al. A systematic literature review of the clinical and health economic burden of schizophrenia in privately insured patients in the United States. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2018;10:309–320.

- Loftus J, Camacho-Hubner C, Hey-Hadavi J, et al. Targeted literature review of the humanistic and economic burden of adult growth hormone deficiency. Curr Med Res Opin. 2019;35(6):963–973.

- Schultz NM, Bhardwaj S, Barclay C, et al. Global burden of dry age-related macular degeneration: a targeted literature review. Clin Ther. 2021;43(10):1792–1818.

- Dussart C, Gelas J, Geffroy L, et al. Medico-economic study of pain in an emergency department: a targeted literature review. J Mark Access Health Policy. 2019;7(1):1659099.

- Yeh YC, Yu X, Zhang C, et al. Literature review and economic evaluation of oral and intramuscular ziprasidone treatment among patients with schizophrenia in China. Gen Psychiatr. 2018;31(3):e100016.

- Németh B, Fasseeh A, Molnár A, et al. A systematic review of health economic models and utility estimation methods in schizophrenia. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2018;18(3):267–275.

- Fautrel B, Boonen A, de Wit M, et al. Cost assessment of health interventions and diseases. RMD Open. 2020;6(3):e001287.

- Tai BB, Bae YH, Le QA. A systematic review of health economic evaluation studies using the patient’s perspective. Value Health. 2016;19(6):903–908.

- Anggraeni M, Gupta J, Verrest HJLM. Cost and value of stakeholders participation: a systematic literature review. Environ Sci Policy. 2019;101:364–373.

- Vieta A, Badia X, Sacristán JA. A systematic review of patient-reported and economic outcomes: value to stakeholders in the decision-making process in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Clin Ther. 2011;33(9):1225–1245.

- Xu L, Xu T, Tan W, et al. Household economic burden and outcomes of patients with schizophrenia after being unlocked and treated in rural China. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2019;29:e81.

- Mangalore R, Knapp M. Cost of schizophrenia in England. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2007;10:23–41.

- Oliva-Moreno J, Lopez-Bastida J, Osuna-Guerrero R, et al. The costs of schizophrenia in Spain. Eur J Health Econ. 2006;7(3):182–188.

- Guest JF, Cookson RF. Cost of schizophrenia to UK society. An incidence-based cost-of-illness model for the first 5 years following diagnosis. Pharmacoeconomics. 1999;15(6):597–610.

- Wu EQ, Birnbaum HG, Shi L, et al. The economic burden of schizophrenia in the United States in 2002. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(9):1122–1129.

- Frey S. The economic burden of schizophrenia in Germany: a population-based retrospective cohort study using genetic matching. Eur Psychiatry. 2014;29(8):479–489.

- Desai PR, Lawson KA, Barner JC, et al. Estimating the direct and indirect costs for community-dwelling patients with schizophrenia. J Pharm Health Ser. Res. 2013;4(4):187–194.

- Heider D, Bernert S, König HH, et al. Direct medical mental health care costs of schizophrenia in France, Germany and the United Kingdom - findings from the European schizophrenia cohort (EuroSC). Eur Psychiatry. 2009;24(4):216–224.

- Barbosa WB, Costa JO, de Lemos LLP, et al. Costs in the treatment of schizophrenia in adults receiving atypical antipsychotics: an 11-year cohort in Brazil. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2018;16(5):697–709.

- Anderson M, Revie CW, Quail JM, et al. The effect of socio-demographic factors on mental health and addiction high-cost use: a retrospective, population-based study in Saskatchewan. Can J Public Health. 2018;109(5–6):810–820.

- Jerrell JM, McIntyre RS, Tripathi A. Incidence and costs of cardiometabolic conditions in patients with schizophrenia treated with antipsychotic medications. Clin Schizophr Relat Psychoses. 2010;4(3):161–168.

- Kearns B, Cooper K, Cantrell A, et al. Schizophrenia treatment with second-generation antipsychotics: a multi-country comparison of the costs of cardiovascular and metabolic adverse events and weight gain. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2021;17:125–137.

- Abouzaid S, Tian H, Zhou H, et al. Economic burden associated with extrapyramidal symptoms in a Medicaid population with schizophrenia. Community Ment Health J. 2014;50(1):51–58.

- Kadakia A, Brady BL, Dembek C, et al. The incidence and economic burden of extrapyramidal symptoms in patients with schizophrenia treated with second generation antipsychotics in a Medicaid population. J Med Econ. 2022;25(1):87–98.

- Rice DP, Miller LS. The economic burden of schizophrenia: conceptual and methodological issues, and cost estimates. In: Moscarelli M, Rupp A, Sartorius N, editors. Handbook of mental health economics and health policy. Volume 1: schizophrenia. Oxford: Wiley; 1996. p. 321–334.

- Zhu B, Ascher-Svanum H, Faries DE, et al. Costs of treating patients with schizophrenia who have illness-related crisis events. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:72.

- Goeree R, O'Brien BJ, Goering P, et al. The economic burden of schizophrenia in Canada. Can J Psychiatry. 1999;44(5):464–472.

- Goeree R, Farahati F, Burke N, et al. The economic burden of schizophrenia in Canada in 2004. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005;21(12):2017–2028.

- Marcellusi A, Fabiano G, Viti R, et al. Economic burden of schizophrenia in Italy: a probabilistic cost of illness analysis. BMJ Open. 2018;8(2):e018359.

- Knapp M, Mangalore R, Simon J. The global costs of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2004;30(2):279–293.

- Tarricone R, Gerzeli S, Montanelli R, et al. Direct and indirect costs of schizophrenia in community psychiatric services in Italy. The GISIES study. Interdisciplinary study group on the economic impact of schizophrenia. Health Policy. 2000;51(1):1–18.

- Haro JM, Salvador-Carulla L, Cabases J, et al. Utilization of mental health services and costs of patients with schizophrenia in three areas of Spain. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;173:334–340.

- Cloutier M, Aigbogun MS, Guerin A, et al. The economic burden of schizophrenia in the United States in 2013. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(6):764–771.

- Lavallee C, Maughn K, Gyanani A, et al. Real-world evidence investigation on healthcare utilization and cost among negative symptom patients and non-negative symptom patients in the USA. PMH25. Value in Health. 2019;22(suppl 2):S230.

- Sicras-Mainar A, Maurino J, Ruiz-Beato E, et al. Impact of negative symptoms on healthcare resource utilization and associated costs in adult outpatients with schizophrenia: a population-based study. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:225.

- Knapp M, McCrone P, Leeuwenkamp O. Associations between negative symptoms, service use patterns, and costs in patients with schizophrenia in five European countries. Clinc Neuropsych. 2008;5(4):195–205.

- Steinert T, Krueger M, Gebhardt RP. Costs of treatment and outcome measures in schizophrenia. Eur J Psychol Assess. 1999;13:209–214.

- Nicholl D, Akhras KS, Diels J, et al. Burden of schizophrenia in recently diagnosed patients: healthcare utilisation and cost perspective. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26(4):943–955.

- Wilson LS, Gitlin M, Lightwood J. Schizophrenia costs for newly diagnosed versus previously diagnosed patients. Am J Pharm Benefits. 2011;3(2):107–115.

- Pennington M, McCrone P. The cost of relapse in schizophrenia. Pharmacoeconomics. 2017;35(9):921–936.

- Haynes VS, Zhu B, Stauffer VL, et al. Long-term healthcare costs and functional outcomes associated with lack of remission in schizophrenia: a post-hoc analysis of a prospective observational study. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:222.

- Jin H, Mosweu I. The societal cost of schizophrenia: a systematic review. Pharmacoeconomics. 2017;35(1):25–42.

- Bobes J, Arango C, Garcia-Garcia M, et al. Prevalence of negative symptoms in outpatients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders treated with antipsychotics in routine clinical practice: findings from the CLAMORS study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(3):280–286.

- Rabinowitz J, Werbeloff N, Caers I, et al. Negative symptoms in schizophrenia–the remarkable impact of inclusion definitions in clinical trials and their consequences. Schizophr Res. 2013;150(2–3):334–338.

- Galderisi S, Mucci A, Buchanan RW, et al. Negative symptoms of schizophrenia: new developments and unanswered research questions. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(8):664–677.

- Rabinowitz J, Levine SZ, Garibaldi G, et al. Negative symptoms have greater impact on functioning than positive symptoms in schizophrenia: analysis of CATIE data. Schizophr Res. 2012;137(1-3):147–150.

- Foussias G, Agid O, Fervaha G, et al. Negative symptoms of schizophrenia: clinical features, relevance to real world functioning and specificity versus other CNS disorders. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;24(5):693–709.

- Erhart SM, Marder SR, Carpenter WT. Treatment of schizophrenia negative symptoms: future prospects. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32(2):234–237.

- Weber S, Scott JG, Chatterton ML. Healthcare costs and resource use associated with negative symptoms of schizophrenia: a systematic literature review. Schizophr Res. 2022;241:251–259.

- Sado M, Inagaki A, Koreki A, et al. The cost of schizophrenia in Japan. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013;9:787–798.

- Davies LM, Drummond MF. Economics and schizophrenia: the real cost. Br J Psychiatry. 1994;165(S25):18–21.

- Ahn J, McCombs JS, Jung C, et al. Classifying patients by antipsychotic adherence patterns using latent class analysis: characteristics of nonadherent groups in the California Medicaid (Medi-Cal) program. Value Health. 2008;11(1):48–56.

- Pesa JA, Doshi D, Wang L, et al. Health care resource utilization and costs of California Medicaid patients with schizophrenia treated with paliperidone palmitate once monthly or atypical oral antipsychotic treatment. Curr Med Res Opin. 2017;33(4):723–731.

- Sarlon E, Heider D, Millier A, et al. A prospective study of health care resource utilisation and selected costs of schizophrenia in France. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:269–276.

- Laidi C, Prigent A, Plas A, et al. Factors associated with direct health care costs in schizophrenia: results from the FACE-SZ French dataset. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2018;28(1):24–36.

- Hirjak D, Hochlehnert A, Thomann PA, et al. Evidence for distinguishable treatment costs among paranoid schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e0157635.

- Esposti LD, Sangiorgi D, Mencacci C, et al. Pharmaco-utilisation and related costs of drugs used to treat schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in Italy: the IBIS study. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:282.

- Cortesi PA, Mencacci C, Luigi F, et al. Compliance, persistence, costs and quality of life in young patients treated with antipsychotic drugs: results from the COMETA study. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:98.

- Esposti LD, Sangiorgi D, Ferrannini L, et al. Cost-consequences analysis of switching from oral antipsychotics to long-acting risperidone in the treatment of schizophrenia (provisional abstract). J Psychopathol. 2012;18(2):170–176.

- Arteaga Duarte C, Colin X, De Moor R, et al. Three-monthly long-acting formulation of paliperidone palmitate is a dominant treatment option, cost saving while adding QALYS, compared to the one-monthly formulation in the treatment of schizophrenia in France. Value Health. 2016;19(7):A378.

- Dilla T, O'Donohoe P, Möller J, et al. Cost-effectiveness of long-acting olanzapine versus long-acting risperidone in patients with schizophrenia in Spain. Value Health. 2011;14(7):A292.

- Davies A, Vardeva K, Loze JGJL, et al. Cost-effectiveness of atypical antipsychotics for the management of schizophrenia in the UK. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24(11):3275–3285.

- Tilden D, Aristides M, Meddis D, et al. An economic assessment of quetiapine and haloperidol in patients with schizophrenia only partially responsive to conventional antipsychotics. Clin Ther. 2002;24(10):1648–1667.

- Almond S, Knapp M, Francois C, et al. Relapse in schizophrenia: costs, clinical outcomes and quality of life. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184(4):346–351.

- Bagnall AM, Jones L, Ginnelly L, et al. A systematic review of atypical antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia. Health Technol Assess. 2003;7(13):1–193.

- Rajagopalan K, Trueman D, Crowe L, et al. Cost- utility analysis of lurasidone versus aripiprazole in adults with schizophrenia. Pharmacoeconomics. 2016;34(7):709–721.