Abstract

There is an ongoing debate among researchers and policy-makers on how to make transparency a powerful tool of healthcare systems. This study addresses how the availability and accessibility of information about medical services to the general population affects healthcare outcomes in Russia. A systematic review was conducted and reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviewing and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines. Transparency indicators of health facilities used in the world’s most efficient healthcare systems are also reviewed. Although the increase of transparency in the Russian healthcare system is considered as a tool for improving its efficiency, very little has been done to improve the actual level of transparency. The existing institutional specifics of the Russian healthcare system impose serious restrictions on acceptable levels of transparency. In the reviewed empirical Russian studies, transparency is often viewed simplistically as either information available on the websites of medical organizations or issues related to the amount of accessible indicators of compulsory medical statistical reporting. The novelty of this study consists in (a) reviewing the most recent studies on the topic and (b) including studies in Russian in the analysis. We elaborate on general and specific policy implications for improving transparency-driven outcomes in the Russian healthcare system.

Introduction

Attention to transparency in healthcare has increased significantly in recent years, as transparency is critical to all aspects of healthcare systems, from the work of individual doctors, medical organizations and insurance companies to the performance of governmentsCitation1. Transparency in healthcare might be particularly prominent across the lower middle-income countries of the Global SouthCitation2. Here the fiscal sustainability of healthcare financing becomes more prominent in comparison to wealthy OECD countriesCitation3. For the purpose of this study, we define transparency as the availability and accessibility of information to the general population on the activities of medical organizations, health authorities, medical insurance funds and insurance companies.

Vukovic et al. analysed 62 papers published in English between 1988 and 2015 to evaluate the influence of public reporting on quality improvement, the healthcare provider’s perspective, healthcare consumers’ experience, service utilization, market share, and unintended consequencesCitation4. The results demonstrated that public reporting is associated with changes in medical providers’ behaviour and can affect market share. However, unintended consequences, such as “stinting on care, or directing exclusive attention to measured performance, to the detriment of important but unmeasured dimensions of care”Citation4, which are driven by potential attempts of healthcare provides to achieve their “targets” without improving the care delivered to patients, should be taken into account in public data release. The results of this review provide a description of how public reporting influences patients’ opinions of healthcare provider quality and helps patients to make better choicesCitation5.

Similar results were obtained in the literature review by Aydin et al.Citation6. The authors analysed 39 empirical studies published in English between 2010 and 2015 to demonstrate the effects of transparency on healthcare results. The findings confirmed a rise in healthcare transparency initiatives and showed mixed results regarding their influence on medical outcomes. Few articles related to the unintended consequences of public data release, which is considered to be a sign of their reduction. The results of this review can be used to understand the consequences of existing transparency efforts and to develop new transparency initiatives to improve the quality performance of medical organizations, especially in post-socialist countriesCitation2.

However, the review by Metcalfe et al. (2018) revealed different resultsCitation7. The authors analysed 12 studies published in English from the US, Canada, Korea, China, and the Netherlands. They checked how the published information about the quality and performance of medical institutions and doctors changed the behaviour of patients and healthcare providers and how it affected healthcare organization performance, healthcare consumer outcomes, and medical staff morale. The studies used for this review were published up to June 2017. The results showed that the evidence of the benefits of public performance data release are insufficient to directly influence policy and practice. More studies should be conducted to consider whether the public release of performance data can improve healthcare consumers’ experience, healthcare processes, and outcomesCitation8.

Our primary research question (RQ1) is: How does the availability and accessibility of information about medical services (i.e. transparency) for the general population affect healthcare outcomes and the efficiency of the Russian healthcare system? In other words, what is the impact of transparency constraints on the performance of medical organizations and what is the impact of transparency constraints on healthcare system efficiency? In order to address RQ1, we have to answer the following questions. RQ2: Which transparency indicators are typically used in the most efficient healthcare systems? RQ3: Which indicators are typically used to measure healthcare system efficiency? RQ4: What are the policy implications for increasing the transparency of healthcare systems worldwide, and specifically for Russia?

The contribution of this study consists in: (a) reviewing the impact of transparency constraints on the efficiency of healthcare outcomes globally and across major regions, (b) revealing the most informative and useful transparency and efficiency indicators in healthcare, (c) obtaining the newest insights from empirical studies, including those in Russian, on the effect of transparency on healthcare outcomes, which was not covered by previous reviews, and (d) elaborating policy recommendations tailored to Russia and countries with similar healthcare systems.

This introduction is followed by theoretical framework, the overview of research procedure, results, policy implications, discussion, and conclusions.

Relation to the literature and the regional specifics of transparency in healthcare

Defining key terms

In this subsection, we provide working definitions for the transparency, effectiveness, and efficiency of healthcare systems.

Transparency is a public value that requires that citizens are informed about how and why decisions are made, including procedures, criteria applied by government decision makers, the evidence used to reach decisions, and results. Often transparency refers to access to information.Citation9, p.2

For the purpose of this study, we define transparency as the availability and accessibility of information to the general population. More specifically, it refers to information on the activities of institutions of the healthcare system, such as medical organizations, health authorities, federal and regional funds of compulsory medical insurance, and insurance companies. It includes: (a) the transparency of the conditions on the provision of medical care for the population, (b) the transparency of institutions (rules) on resource allocation in the healthcare system and (c) the transparency of the outcomes of healthcare system institutions.

Effectiveness is usually related to healthcare service delivery, which is based on scientific knowledge and results in improved health outcomes. Health services are provided to all who could benefit and not provided to those who do not need them (see, e.g. Araujo et al.Citation10).

Efficiency is usually associated with healthcare services delivered in a manner, which maximizes resource use and avoids waste, including the waste of equipment, supplies, ideas, and energy. It is aimed at the greatest health improvement at the lowest cost, with the most advantageous cost-benefit (see, e.g. Araujo et al.Citation10) According to the results of Ravaghi et al.Citation11, 41% of studies used data envelopment analysis to estimate the effectiveness of medical organizations with output variables, such as the number of inpatients, the number of ambulances, health worker costs, etc. These absolute indicators, which are measured without any relation to healthcare outcomes, provide little information on either the effectiveness or efficiency of hospitals and healthcare systems.

We consider the efficiency of healthcare systems as a synonym to efficient healthcare system outcomes or the efficient aggregate performance of medical organizations in terms of standard healthcare performance (not financial performance) using indicators, such as mortality per 1,000 surgeries, the prevalence of major diseases, etc.

Global perspective

Over the past 20 years, healthcare organizations have increased their efforts to improve the efficiency and quality of their healthcare provisionCitation12,Citation13. They used transparency as a means to stimulate system enhancement by providing access to information about the efficiency of medical organizations to the public. Even though there are many advocates of healthcare transparency, some studies show its risks.

For example, Canaway et al.Citation14 noted that the public reporting system in Australia, which is a driver of transparency, has a number of flaws that are also common to other countries. First of all, there is a lack of clear aim for the information provision. There is also no consensus on who the main audience is, whether it is patients, government bodies, or other stakeholders. These fundamental issues require a solution as the way the information is presented depends on the audienceCitation14.

This leads to the problem of using the appropriate metrics for each group of stakeholders that are not only understandable, but also useful for stimulating the greater efficiency of medical organizations. The information should be presented with proper explanation of the indicators used that correspond to the needs of the main audience. Therefore, healthcare indicators should also be disclosed with cautionary and explanatory notes to the public, otherwise it brings only confusion and lessens the potential of information accessibilityCitation15–17.

According to Baccolini et al.Citation18, who report on healthcare performance and those who interpret it, such attention towards the explanation of the indicators is necessary due to poor health literacy. Patients are advised to become more active and engaged in their healthcare and look for the information about their medical options, thus creating a “healthcare consumerist culture” that drives clinical and hospital enhancements. However, in some cases, patients are not aware of the availability of the required information or may have issues with access to it. This problem is especially relevant to elderly patientsCitation18.

One more issue with transparency in healthcare is the discrepancies in the published data due to the poor measurement systems used or their politicizationCitation15,Citation16,Citation19. For example, depending on the rating system applied, the same hospital may be considered as having both low and high levels of mortalityCitation20. Such cases not only confuse stakeholders but also reduce the level of trust in the reports and value of such reports in general.

However, the discrepancies of the provided data may also appear due to medical professionals or institutions’ “gaming” itCitation14,Citation17,Citation21. For example, the doctors may avoid “difficult” patients in order to report better outcomes and obtain incentives for better results. This brings into question the validity of the information provided and raises concerns about “hidden” data, both of which hinder the improvement of the system. Such behaviour of doctors may be explained by the transparency strategy itself. Even though it is not aimed at blaming doctors for errors, but rather medical organizations, in some cases, only the individual doctors face the consequences of errors that lead to prosecutionCitation22. Hospitals, in turn, may avoid patients with serious illnesses as they negatively affect their quality performance resultsCitation21.

Not only are individual doctors reluctant to share data, but also healthcare institutions and units within them. They are afraid of the risks and unfair changes such information may cause themCitation14,Citation22.

Transparency of information did not succeed in increasing the efficiency of healthcare results without market pressure. This influenced the quality of healthcare in different ways depending on the unique features of transparency policies. However, the availability of healthcare information failed to bring necessary changes to those policies and, in some cases, the reporting of healthcare data was forbidden by the governmentCitation21.

Summing up, the advantages of transparency initiatives for healthcare efficiency are: (1) improving the quality and consistency of healthcare provision, (2) increasing patients’ trust in healthcare providers, (3) improving healthcare outcomes and the level of patient satisfaction, and (4) informing patients about the quality of healthcare providers. On the other hand, the disadvantages include: (1) a lack of clear aims and a proper explanation of the metrics used in public reporting on the quality of healthcare providers, (2) poor health literacy of those who report on healthcare performance and those who interpret it, (3) a lack of awareness and access to the information of the performance of healthcare organizations among patients, (4) discrepancies of the published data due to the poor measurement systems used or its politicization, and (5) “gaming” healthcare data by medical professionals or institutions.

Even though these transparency constraints can be common to various national contexts, there are differences among countries that are discussed in the following sections.

The US perspective

The US healthcare system is shifting towards patient-centred processes and transparencyCitation19. For example, online review systems are being implemented and expandedCitation19, all-payer claims data are being disclosedCitation21, price transparency requirements are being establishedCitation23, transparent succession management practices are being introduced etc.Citation24. However, all these initiatives have a number of flaws. According to KordzadehCitation19, only some types of healthcare institutions provide online review systems. Such systems, moreover, show inconsistent results as they use different instruments for assessing patients’ healthcare experiences, making it impossible to compare different hospitals. Han and LeeCitation21 demonstrate that the disclosure of all-payer claims data fails to differentiate medical centre quality without considering market pressure. According to Berkowitz et al.Citation23, despite new price transparency requirements, some standard medical charges remain unclear and vary depending on the hospital and its location.

European perspective: the EU and the UK

The European and UK healthcare systems are focusing on improving the quality of healthcare provision by promoting a culture of transparency and considering resources and cost efficiencyCitation22,Citation25,Citation26. However, compared to the EU countries, the UK has advanced further in fostering a culture of transparency. For example, only the UK publishes overall rankings for general practices and key healthcare institutions. Only the UK provides information on mortality rates achieved by every doctor nationally and a complex rating of the general quality of care in hospitalsCitation26. However, there is little evidence of any positive impact of these transparency initiatives on healthcare outcomes. There is, however, evidence of a negative influence on some individual doctors when the cases of their medical errors were publicizedCitation22. These transparency constraints are also common to some EU countries like the Netherlands, France, and GermanyCitation26.

Asian perspective: China and Japan

ChineseCitation27 and JapaneseCitation28 medical systems are moving towards organizational transparency which leads to patient well-being and quality enhancementCitation29–31. A number of initiatives were introduced: information disclosure of medical management, treatment, healthcare quality, finances, medical errors, and patient satisfaction surveysCitation29–31. Despite all the benefits of transparency in healthcare, such as the improvement of patient awareness, safety, and satisfaction, several studies point out a number of constraints. Firstly, error reporting may be highly subjective, biased, and incomparable among different medical institutionsCitation31. Secondly, the higher the transparency, the higher the patients’ expectations about healthcare services, which diminishes the positive effects of medical treatment quality and perceived value on patients’ level of satisfactionCitation30. Thirdly, the interpretation of the data may be difficult to understand for people outside the healthcare industryCitation29.

Russian perspective

The increase of transparency in the Russian healthcare system is considered as a tool for improving its efficiency in terms of resources and clinical results. However, very few initiatives have been implemented to improve the actual level of transparency. Most studies were devoted to the analysis of the websites of medical organizations and statistical reporting that had many issues and discrepanciesCitation32–34. Such reporting may lead to misinformation about the current state of healthcare and people’s mistrust of the medical system in general. The features and specifics of the Russian healthcare system impose some restrictions on acceptable levels of transparencyCitation35–Citation37. Thus, the rapid intensification of transparency may lead to negative consequences that may jeopardize the stable functioning of the healthcare system in RussiaCitation32.

Methods

Design

We employed a systematic review to identify and classify all the literature that is related to our research questions, following the PRISMA and ENTREQ reporting guidelinesCitation38,Citation39. This review has a results-based convergent synthesis design. This means that quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-methods research studies are found in a single search. They are then presented, described, and examined separately, and finally integrated during the data summaryCitation40,Citation41. In conducting this review, the steps were followed as outlined below: (1) a methodical search of literature, (2) data extraction, and (3) data integration and presentation.

Search strategy (algorithm)

We searched the following electronic databases: Scopus, Web of Science, and Russian Science Citation Index. We developed search terms for the main concepts related to the topic of our interest (e.g. transparency, information availability) and the relevant outcomes of medical organizations and healthcare systems in general (e.g. medical organizations, hospitals, healthcare system). The final search terms were: “transparency” OR “information availability” OR “information accessibility” AND “medical organization” OR “healthcare facility” OR “hospital” AND “effective care” OR “efficient care” OR “timely care” OR “healthcare outcomes” OR “surgical outcomes” OR “mortality” OR “readmission” OR “number of recoveries”. These keywords were searched for in the abstracts and/or titles of the respective articles. We focused our search on publications in English and Russian, published in 2016–2022 and in 2014–2022, respectively. The search algorithm in Russian was adjusted slightly according to the specifics of Russian terminology by, for example, adding Russian synonyms of key terms and relevant abbreviations. We also conducted a manual search of the reference lists of the research papers found in the initial search.

Search inclusion/exclusion criteria

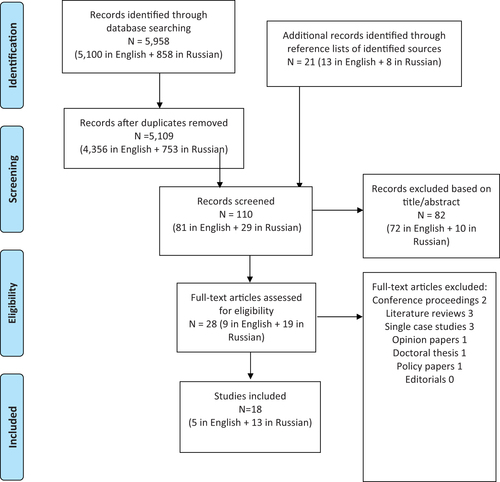

The initial search returned 5,958 publications in English and Russian, which were transferred into Endnote where duplicates were removed; 5,109 articles remained. The titles and abstracts of these articles were scanned, and articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria were removed. Subsequently, 89 articles were left and a second full-text screen was carried out and references were examined. After that, 21 additional studies were identified and all 110 research papers were evaluated against the eligibility criteria listed below, leaving five research papers in English and 13 publications in Russian. The PRISMA diagram demonstrates our search for eligible studies (see ). and summarize the articles in English and Russian, which were included in the analysis, respectively.

Table 1. Overview of the main analysed studies published in English.

Table 2. Overview of the main analysed studies published in Russian (authors’ translations).

We included publications if: (a) they included empirical data; (b) they were peer reviewed; (c) they had extractable data related to transparency [availability, accessibility, openness] of information on healthcare services; and (d) they belonged to the “research article” or “original study” type. We excluded publications of the following types: (a) expert opinion, (b) single-case study, (c) (systematic) literature review, (d) conceptual theoretical study, (e) editorial and (f) commentary. Literature reviews, which were found during the preliminary search, were summarized in the background section.

Data extraction procedure

We extracted data from the 18 studies and categorized according to the source, country, research methods/design, data, and main findings (see ). We kept categories broad due to methodological variances across and within research papers and, therefore, summary measures were not possible.

Data summary and synthesis

We combined articles to summarize descriptive statistics of the study characteristics, followed by a textual narrative synthesis. Such methods place different study types into more homogeneous subgroups. This helps in the synthesis of diverse types of evidence. It also helps to answer the research questions using different methodological approachesCitation42.

Results

The most informative and useful indicators of transparency

provides an overview of proxy-variables for “transparency” used in empirical studies related to Asia, Western Europe, and North America. Noteworthy, the transparency indicators used by the governments of the respective countries can essentially differ from their “academic analogues”.

Table 3. Overview of proxy-variables for “transparency” used in empirical studies.

In studies on healthcare system transparency in North America, scholars use the following indicators: the share of hospitals that successfully presented their performance on outpatient imaging effectivenessCitation21, the availability of standard charges (i.e. price transparency) and usability metricsCitation23,Citation43, the availability of data on medical errorsCitation44, the availability of online patient reviewsCitation19, and the degree of accessible data on patient satisfactionCitation21. According to research from Western Europe, major transparency-related indicators include, but are not limited to: the availability of a patient rights chart, waiting times, waiting lists, budgets, and professionals’ biographical sketches on healthcare facilities’ websitesCitation45, hospital managers’ perceptions of information retrieval, non-financial reporting, financial reporting and public disclosureCitation46, and survey-based openness scoresCitation22,Citation47. Asia-related studies rely on the following indicators: the disclosure of medical management, treatment and quality, the disclosure of financial statements, the disclosure of information about violations, the disclosure of the insured bed ratio, awareness and concernsCitation29, consumer satisfactionCitation30, and the reporting of incidents by doctorsCitation31.

Rechel et al.Citation26 map approaches to public reporting on waiting times, patient experience, and cumulative measures of quality and safety in 11 high-income countries (Australia, Canada, England, France, Germany, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland and the US). Their results suggest that most common, publicly available information refers to waiting times for hospital treatment and patient experiences. However, the latter is not usually available in terms of primary care services. Only England, out of the 11 examined countries, publishes multiple measures of overall quality and safety of care that allow the ranking of medical organizations. Likewise, the publication of information on the results of individual doctors remains rare.

In the Russian literature, typical transparency indicators refer to information accessible on healthcare facilities’ websites. In Russian public healthcare facilities, information accessibility is determined by federal legislation. However, only one fifth of healthcare facility websites fully meet the basic requirementsCitation48. Interestingly, this result is similar to the findings by Haque et al.Citation43 who demonstrated that “most US hospitals remained noncompliant with the CMS-1694-F ruling, and compliance was associated with patient ratings, hospital type, and ownership. Even when publicly accessible, chargemasters were frequently buried within websites and difficult to use accurately”. Omelyanovsky et al.Citation32 report that Russian medical organizations very often provide low-quality reports with statistical errors and deliberate distortions of the data. In Russia, more and diverse information can be found on the websites of private healthcare facilitiesCitation48. Notably, the state federal and regional monitoring authorities, such as the Federal Service for Surveillance in Healthcare (Roszdravnadzor), collect very detailed data on healthcare facilities’ financial and healthcare performanceCitation49. However, much of this data is not accessible to the general public.

In Russia, the poor quality of accessible information can be partially explained by the fact that mechanisms for providing official statistical accounting information to other potential users (citizens and organizations, including for scientific purposes) are not provided for by lawCitation32. In addition, issues of quality control and the safety of medical activities have a low priority in the activities of regional health authorities in RussiaCitation50.

Typically used healthcare system efficiency indicators

Before we proceed to our main research question, we identify how our target indicator differs among countries, especially in those with the best healthcare system outcomes.

Healthcare efficiency indicators can be divided into two groups: objective (e.g. the relative number of errors, patient waiting times) and subjective (e.g. patient satisfaction). Not surprisingly, there are differences in measuring healthcare outcomes and, therefore, healthcare effectiveness among countries. In , we summarize those related to very diverse healthcare systems across the globe, which are used in empirical studies. The noteworthy examples include studies by Arnetz et al.Citation51, Hota et al.Citation52, Jacobs and JacobsCitation53, Raeissi et al.Citation54 and Weeks et al.Citation55. Assessing technical efficiency is one of the most popular approaches to measuring healthcare system efficiency in many countries (for example, see Han et al.Citation21 in the US, Storto et al.Citation25 in 32 European countries; Jiang et al.Citation56 in China; and Zhang et al.Citation57 in Japan). Devasahay et al.Citation58 provide the most recent systematic review of key performance indicators used for measuring team performances in hospitals.

Table 4. Overview of proxy-variables for “healthcare system efficiency” and “healthcare outcomes” in empirical studies.

In official reports to state authorities, Russian healthcare facility managers have to use the following indicators: fulfilment of the state order (target indicators set by the federal government for each fiscal years), number of justified complaints, satisfaction with the quality of medical care provided, the implementation of plans to achieve salary ratios, the (completeness of) coverage by doctors and nurses, proportion of visits with a preventive purpose, neonatal coverage medical supervision/patronage, vaccination coverage, average duration of stay of the inpatients, the percentage of emergency calls with a waiting time of less than 20 min, the proportion of discrepancy between the diagnosis of the emergency from the reception department of the medical organization (see, e.g. Saitgareeva et al.Citation59).

The effect of transparency on healthcare outcomes: global perspective

The five reviewed English-language studies, although diverse in terms of both methodology and results, are united by considering transparency and openness as drivers of healthcare system efficiency, see for details on each study. According to a qualitative interview-based study by Canaway et al.Citation14, a weakness of public reporting (PR) of hospital performance data perceived by consumers, providers, and purchasers in Australia consists in the fact that “the public are often not considered its major audience, resulting in information ineffectually framed to meet the objective of PR informing consumer decision-making about treatment options”. The findings of Canaway et al.Citation14 suggest that public reporting should drive quality, safety, and performance improvements. The results of the following three quantitative studies clearly indicate the positive impact of transparency. Selvaratnam et al.Citation60, by performing an interrupted time-series analysis, document that, in Australia, the public reporting of a fetal-growth restriction performance indicator was associated with the improved detection of severe cases of babies small for gestational age and a decrease in the rate of stillbirths. Toffolutti and StucklerCitation22, using English acute care hospital data, demonstrate that a one-point increase in the standardized openness score was associated with a 6.48 percent reduction in English hospital mortality rates. Han et al. Citation21, utilising data from general acute care hospitals across the US, measure the relationships between transparent policies and technical efficiency. They recommend policymakers consider introducing competition together with the introduction of public reporting schemes to get the best outcomes from the US healthcare system. In contrast, the results of the randomized controlled trials documented by Arkedis et al.Citation61 demonstrate that the influence of a transparency and accountability program designed to improve maternal and new-born health (MNH) outcomes in Indonesia and Tanzania was insignificant.

The effect of transparency on healthcare outcomes: Russian perspective

There is contradictory empirical evidence coming from the articles in Russian on the effects of information accessibility on patient satisfaction, which can serve as a proxy for healthcare efficiency. A survey-based study by DavydovCitation62 suggests that patient satisfaction with the quality of the information provided on the healthcare facility activities in the Republic of Mordovia (East European part of Russia) is currently at a high level. In contrast, according to the results of an online survey by Garina et al.Citation63, a slight growth in the number of citizens’ appeals to authorities in connection with dissatisfaction in the provision of medical care is associated with the increased legal activity of the population and the openness of information of medical organizations in Moscow region.

Results of an interview-based study, conducted in the Republic of Tatarstan and Republic of Mari-El (both republics are located in East European part of Russia) by Savel’eva et al.Citation64 suggest that new information technologies have had a positive influence on openness and accessibility in the Russian healthcare system. However, there are some profound negative issues related to implementation, such as: (a) a lack of information provided to the public concerning state warranties of healthcare programs; (b) poor IT support of healthcare facility websites; and (c) age inequality in access to information about the services and in online booking of doctor’s appointmentsCitation64.

Utilising a survey of 50 pharmaceutical employees in the city of Khabarovsk (Russian Far East), Gnatyuk et al.Citation65 conclude that the information accumulated in the Unified Regional Information System is not accessible by patients. It does not allow for compliance with the basic requirements of good pharmacy practice, such as orientation toward the patient in order to preserve human health, promoting the rational prescription and appropriate use of medicines, and the orientation of each element of the pharmaceutical service to the individualCitation66. Employing content analysis of public healthcare facility websites in Stavropol region (South West of Russia), Murav’yova et al.Citation67 revealed common problems of these websites, which lead to inefficiencies in providing healthcare. On the one hand, there is insufficient information, which is of interest to patients, on transport accessibility, preferential medicines, health insurance companies providing compulsory medical insurance and regulatory organizations. On the other hand, the websites have poor usability due to poor design, low resolution of images, etc. These problems are caused by the formal minimalistic approach of poorly motivated website creators. These finding are supported by the results of similar studies by (a) Abramova et al. Citation33, Khodakova and Evstaf’evaCitation34 and (c) Ekkert and PolukhinCitation48 and PolukhinCitation35, who provide evidence from Zabaykalskiy Region (Russian Far East), the Republic of Mordovia, and Moscow region, respectively. According to the results of content analysis conducted by BidarovaCitation68, the majority of regional divisions of the Federal Service for Surveillance in Healthcare, a federal service at the Ministry of Health that controls the quality of healthcare provision, do not provide open data on their websites on the results of control and supervisory measures.

Policy recommendations for Russia

Insights on perceived barriers for the implementation of effective public reporting are discussed by Canaway et al.Citation14. Major barriers are conceptual (e.g. a lack of understanding of the benefits), systemic (related to deficiencies in the organization of the health system, including bureaucratization), technical and resource (e.g. lack of necessary infrastructure), and socio-cultural (for example, the illiteracy of the population on health issues, a fear of healthcare facility representatives, and the lack of complete and honest reporting on some performance indicators). The recommendations below aim at optimizing the Russian healthcare system and can be applicable in a number of other post-Soviet countries.

In order to improve information availability for the population, healthcare facility managers should receive sufficient specialized training, which would help them to optimize relevant decision-making regarding the volume and forms of public reporting and to comply with legislationCitation35,Citation36,Citation48. It would be useful to optimize the content of mandatory reportingCitation32 by defining the necessary elements and the procedure for its public presentation. State guarantee programs, in terms of the volume and procedures for providing free medical care to the population, should be widely discussed by the expert community with the involvement of the media and, ideally, an additional open public discussion before their legislative approvalCitation35,Citation36. The regular reporting of the solutions provided for patient appeals on healthcare facility websites can help to improve the quality of medical careCitation63. The content of the state-owned healthcare facility websites in terms of information “richness”, functionality, and convenience for patients should be structured in a more client-oriented fashion, using modern interactive functions that allow them to get information quickly and in an understandable formCitation34. For example, for health facilities located in large cities, it would be useful to add a link to an independent resource that compares quality indicators for similar types of medical care and services. The quality of medical care can be improved when objective parameters, which are understandable to the general public, such as an independent quality assessment of medical servicesCitation62.

In the Russian pharmaceutical market, the availability of information reported by licensed pharmaceutical market participants would restore public confidence. Providing highlights from Roszdravnadzor reports on the results of legal compliance-related inspections of pharmaceutical companies and pharmacies would ensure the quality, safety, and accessibility of drug treatment. The latter is especially important for citizens entitled to free prescriptions who have been negatively affected, among other things, by inaccurate media reportsCitation68,Citation69. This is in line with the general policy recommendations developed by Paschke et al.Citation70.

The following two conditions will determine the implementation success of the proposed policy recommendations. Firstly, it is necessary to take into account the existing barriers, mentioned above, in relation to Russian characteristics (for example, the lack of technical ability to familiarize the general public with published potentially useful information, especially among the elderly and residents of remote areas, as well as the habit of not disseminating optional information by representatives of medical organizations. Secondly, a pilot stage followed by a regulatory impact assessment is a necessary condition for the implementation of each measure.

Discussion and conclusions

There is no simple recommendation on the extent to which healthcare facilities should be transparent in order to improve healthcare outcomes. One needs to know what kind of transparency (information availability or information accessibility) positively affects healthcare system efficiency. Typically, governments regulate what kind of information should be made public. The list of indicators depends on the country. In Russia, state-owned healthcare facilities prefer to provide a minimum of information to third parties unless it is required by law. The major reason for the transparency constraint is twofold. First, they do not have enough resources to maintain high-quality access to specific information on their performance indicators. Second, facility managers try to avoid unwanted consequences from “excessive” transparency, such as patient claims with consequent audits by state authorities, and a potential decrease in bonuses.

The empirical findings related to Russia are driven by the nature of the inherited healthcare systemCitation37. For example, the “imitation” of transparency through providing a lack of relevant information for patients on healthcare facility websites is caused by systemic and institutional problems, such as unclearly documented recipients of transparency policy, lack of cooperation among the stakeholders of this policy, poorly paid staff, and a high differentiation among rural and urban areas. More specific transparency constraints of Russia’s healthcare system, which negatively affect its efficiency as well, include, but are not limited to the following: there is (a) no monitoring of waiting times for planned medical care through a centralized information portal, (b) closed access to information about the allocation of compulsory insurance funds among healthcare facilities of similar types, (c) outdated procedure for adjusting planned volumes of medical care during the year, (d) difficult access to information about distribution of budget subsidies among medical organizations for the purchase of expensive medical equipment, and (e) accessing medical care efficiency without taking into account the complexity of patients’ illnesses.

Therefore, we would not recommend employing either the North American experience of medical error communication (e.g. Bell et al.Citation44) the Japanese experience of public reporting accidents by medical doctors (e.g. Fukami et al.Citation31) or other unfavourable transparency indicators in Russia and other countries with similar cultures.

The major limitation of the Russian studies is their methodological restrictions. Typically, Russian research employs either content analysis of legislation or simple descriptions and/or comparisons of healthcare facility websites, sometimes survey-based, but without further non-parametric or parametric statistical analysis. Therefore, further research is necessary to quantify the impact on healthcare outcomes of (a) the existing transparency indicators used in Russia and (b) the major transparency indicators used in the countries with highly efficient healthcare systems.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This article is an output of a research project implemented as part of the Basic Research Program at the National Research University Higher School of Economics.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Author contributions

YT was responsible for the study design and research questions definition, supervised and coordinated the joint efforts. OD collected the data. YT interpreted the results of the analysis. YT and OD drafted the manuscript. MJ revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgements

None.

References

- The National Patient Safety Foundation. The National Patient Safety Foundation Shining a Light. Safer Health Care through Transparency. Boston, MA, USA. 2015; [cited 2022 April 18]. Available from https://psnet.ahrq.gov/issue/shining-light-safer-health-care-through-transparency.

- Jakovljevic M, Liu Y, Cerda A, et al. The global South political economy of health financing and spending landscape–history and presence. J Med Econ. 2021;24(sup1):25–33.

- Jakovljevic M, Cerda AA, Liu Y, et al. Sustainability challenge of Eastern Europe – historical legacy, belt and road initiative, population aging and migration. Sustain. 2021;13(19):11038.

- Vukovic V, Parente P, Campanella P, et al. Does public reporting influence quality, patient and provider’s perspective, market share and disparities? A review. Eur J Public Health. 2017;27(6):972–978.

- Jakovljevic M, Vukovic M, Chen CC, et al. Do health reforms impact cost consciousness of health care professionals? Results from a nation-wide survey in the Balkans. Balkan Med J. 2016;33(1):8–17. 2016

- Aydin R, Zengul FD, Quintana J, et al. Does transparency of quality metrics affect hospital care outcomes? A systematic review of the literature. In: Hefner JL, Al-Amin M, Huerta TR, Aldrich AM, Griesenbrock TE, editors. Transforming health care (Advances in health care management, Vol. 19). Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited; 2020. p. 129–156.

- Metcalfe D, Diaz AJR, Olufajo OA, et al. Impact of public release of performance data on the behaviour of healthcare consumers and providers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;9(9):CD004538–59.

- Jakovljevic M, Sugahara T, Timofeyev Y, et al. Predictors of (in) efficiencies of healthcare expenditure among the leading Asian economies–comparison of OECD and non-OECD nations. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2020;13:2261–2280.

- Vian T. Anti-corruption, transparency and accountability in health: concepts, frameworks, and approaches. Glob Health Action. 2020;13(sup1):1694744.

- Araujo CA, Siqueira MM, Malik AM. Hospital accreditation impact on healthcare quality dimensions: a systematic review. Int J Qual Health Care. 2020;32(8):531–544.

- Ravaghi H, Afshari M, Isfahani P, et al. A systematic review on hospital inefficiency in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: sources and solutions. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):1–20.

- Bates DW, Singh H. Two decades since to err is human: an assessment of progress and emerging priorities in patient safety. Health Aff. 2018;37(11):1736–1743.

- Dash S, Shakyawar SK, Sharma M, et al. Big data in healthcare: management, analysis and future prospects. J Big Data. 2019;6(1):1–25.

- Canaway R, Bismark M, Dunt D, et al. Perceived barriers to effective implementation of public reporting of hospital performance data in Australia: a qualitative study. BMC Health Ser Res. 2017;17(1):1–12.

- Halasyamani LK, Davis MM. Conflicting measures of hospital quality: ratings from “Hospital compare” versus “best hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(3):128–134.

- Austin JM, Jha AK, Romano PS, et al. National hospital ratings systems share few common scores and may generate confusion instead of clarity. Health Aff. 2015;34(3):423–430.

- Wu B, Jung J, Kim H, et al. Entry regulation and the effect of public reporting: evidence from home health compare. Health Econ. 2019;28(4):492–516.

- Baccolini V, Rosso A, Di Paolo C, et al. What is the prevalence of low health literacy in European Union member states? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(3):753–761.

- Kordzadeh N. Toward quality transparency in healthcare: exploring hospital-operated online physician review systems in northeastern United States. Health Policy Technol. 2020;9(1):56–61.

- Shahian DM, Wolf RE, Iezzoni LI, et al. Variability in the measurement of hospital-wide mortality rates. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(26):2530–2539.

- Han A, Lee KH. The impact of public reporting schemes and market competition on hospital efficiency. Healthcare. 2021;9(8):1031.

- Toffolutti V, Stuckler D. A culture of openness is associated with lower mortality rates among 137 English National health service acute trusts. Health Aff. 2019;38(5):844–850.

- Berkowitz ST, Siktberg J, Hamdan SA, et al. Health care price transparency in ophthalmology. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2021;139(11):1210–1216.

- Groves KS. Examining the impact of succession management practices on organizational performance: a national study of US hospitals. Health Care Manage Rev. 2019;44(4):356–365.

- Storto CL, Goncharuk AG. Performance measurement of healthcare systems in Europe. J Applied Manag Invest. 2017;2017(63):170–174.

- Rechel B, McKee M, Haas M, et al. Reporting on quality, waiting times and patient experience in 11 high-income countries. Health Policy. 2016;120(4):377–383.

- Sapkota B, Palaian S, Shrestha S, et al. Gap analysis in manufacturing, innovation and marketing of medical devices in the Asia-Pacific region. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2022;22(7):1043–1050.

- Ogura S, Jakovljevic M. Health financing constrained by population aging: an opportunity to learn from Japanese experience. Serb J Experiment Clin Res. 2014;15(4):175–181.

- Yan YH, Kung CM, Fang SC, et al. Transparency of mandatory information disclosure and concerns of health services providers and consumers. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(1):53.

- Yang Y. Is transparency a double-edged sword in citizen satisfaction with public service? Evidence from China’s public healthcare. J Service Theory Pract. 2018;28(4):484–506.

- Fukami T, Uemura M, Nagao Y. Significance of incident reports by medical doctors for organizational transparency and driving forces for patient safety. Patient Saf Surg. 2020;14(1):13–17.

- Omelyanovsky V, Zheleznyakova I. Совершенствование системы ведомственной статистической отчетности в сфере здравоохранения [Improving the system of departmental statistical reporting in healthcare]. 2019; Russian. [cited 2022 May 29]. Available from: http://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3347552

- Abramova YA, Davydov YA, Lemaikin VF, et al. Анализ качества и доступности предоставления медицинских услуг населению в государственных медицинских организациях республики Мордовия (2016 г.) [Analysis of the quality and accessibility of medical services to the population in state medical organisations of the Republic of Mordovia] Socio-Economic Development of the Republic of Mordovia in Year. Russian. 2016;2019:129–176. https://dentalcollege.ru/upload/iblock/d9a/d9ab8e22fffefad62e0a704fe5492d92.pdf

- Khodakova OV, Evstaf’eva YV. Комплексная оценка официальных сайтов медицинских организаций [The complex assessment of official websites of medical organisations]. Healthc RF. 2019;61(2):70–75. Russian.

- Polukhin NV. Анализ информационного наполнения сайтов медицинских организаций в сети интернет [Content analysis of healthcare facilities’ websites]. Bull Biomed Soc. 2018;3(1):1–4. Russian.

- Savel’eva ZhV, Kuznetsova IB, Mukharyamova LM. Социальная справедливость в здравоохранении: опыт и оценки россиян [Social justice in healthcare in the experiences and judgments of Russians]. Univ Russia Sociol Ethnol. 2018;27(3):154–179. Russian.

- Popovich L, Potapchik E, Shishkin S, et al. Russian Federation: health system review. Health Syst Transit. 2011;13(7):1–190.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int J Surg. 2021;88:105906.

- Tong A, Flemming K, McInnes E, et al. Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12(1):181–188.

- Noyes J, Booth A, Moore G, et al. Synthesising quantitative and qualitative evidence to inform guidelines on complex interventions: clarifying the purposes, designs and outlining some methods. BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4(Suppl 1):e000893.

- Hong QN, Pluye P, Bujold M, et al. Convergent and sequential synthesis designs: implications for conducting and reporting systematic reviews of qualitative and quantitative evidence. Syst Rev. 2017;6(1):1–14.

- Lucas PJ, Baird J, Arai L, et al. Worked examples of alternative methods for the synthesis of qualitative and quantitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7(1):1–7.

- Haque W, Ahmadzada M, Allahrakha H, et al. Transparency, accessibility, and variability of US hospital price data. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(5):e2110109.

- Bell SK, White AA, Jean CY, et al. Transparency when things go wrong: physician attitudes about reporting medical errors to patients, peers, and institutions. J Patient Saf. 2017;13(4):243–248.

- Bucci S, Tanzariello M, Avolio M, et al. Is there a relationship between transparency and outcome in hospital care? An analysis on the Italian public hospitals: Marta Marino. Eur J Public Health. 2014;24(suppl_2):96.

- Zehir C, Çınar F, Şengül H. Role of stakeholder participation between transparency and qualitative and quantitive performance relations: an application at hospital managements. Procedia-Soc and Behav Sci. 2016;229:234–245.

- McCarthy I, Dawson J, Martin G. Openness in the NHS: a secondary longitudinal analysis of national staff and patient surveys. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):1–12.

- Ekkert NV, Polukhin NV. Представление информации для потребителей медицинских услуг на веб-сайтах медицинских организаций: проблемы и пути решения [Presentation of information for consumers of medical services on the websites of health facilities: problems and solutions]. Med Tech Assessment Choice. 2019;3(3 (37):62–70. Russian.

- Reshetnikov V, Mitrokhin O, Shepetovskaya N, et al. Organizational measures aiming to combat COVID-19 in the Russian Federation: the first experience. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2020;20(6):571–576.

- Perkhov VI. О транспарентности обязательного медицинского страхования [About the transparency of compulsory health insurance]. Healthc Manag. 2018;10:14–22. Russian. https://elibrary.ru/download/elibrary_36613592_44770028.pdf.

- Arnetz BB, Goetz CM, Arnetz JE, et al. Enhancing healthcare efficiency to achieve the Quadruple Aim: an exploratory study. BMC Res Notes. 2020;13(1):1–6.

- Hota B, Webb TA, Stein BD, et al. Consumer rankings and health care: toward validation and transparency. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2016;42(10):439–446.

- Jacobs JP, Jacobs ML. Transparency and public reporting of pediatric and congenital heart surgery outcomes in North America. World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg. 2016;7(1):49–53.

- Raeissi P, Reisi N, Nasiripour AA. Assessment of patient safety culture in Iranian academic hospitals: strengths and weaknesses. J Patient Saf. 2018;14(4):213–226.

- Weeks WB, Kotzbauer GR, Weinstein JN. Using publicly available data to construct a transparent measure of health care value: a method and initial results. Milbank Q. 2016;94(2):314–333.

- Jiang S, Min R, Fang PQ. The impact of healthcare reform on the efficiency of public county hospitals in China. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):1–8.

- Zhang X, Tone K, Lu Y. Impact of the local public hospital reform on the efficiency of medium‐sized hospitals in Japan: an improved slacks‐based measure data envelopment analysis approach. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(2):896–918.

- Devasahay SR, DeBrun A, Galligan M, et al. Key performance indicators that are used to establish concurrent validity while measuring team performance in hospital settings – a systematic review. Comput Methods Programs Biomed Update. 2021;1:100040.

- Saitgareeva АА, Budarin SS, Volkova ОА. Показатели и критерии оценки эффективности деятельности медицинских организаций в федеральных и региональных нормативных правовых актах. [Indicators and criteria for evaluating the effectiveness of medical organizations in federal and regional regulatory legal acts]. Vestnik Roszdravnadzora. 2015;(6):12–23. Russian.

- Selvaratnam RJ, Davey MA, Anil S, et al. Does public reporting of the detection of fetal growth restriction improve clinical outcomes: a retrospective cohort study. BJOG. 2020;127(5):581–589. 10.1111/1471-0528.16038

- Arkedis J, Creighton J, Dixit A, et al. Can transparency and accountability programs improve health? Experimental evidence from Indonesia and Tanzania. World Dev. 2021;142:105369.

- Davydov DV. Независимая оценка качества условий оказания услуг медицинскими организациями республики Мордовия в 2018 г.: анализ результатов [Independent assessment of the quality of conditions for the provision of services provided by medical organisations in the republic of Mordovia: analysis of the results. Hum Polit-Legal Sts. Russian. 2019;4(7):54–64.

- Garina IB, Plutnitsky АN, Gurov AN. Основные направления анализа причин неудовлетворенности населения медицинской помощью на основе обращений граждан и независимой оценки качества оказания услуг медицинскими организациями [The main trends of analysis of the causes of patients’ discontent with the medical aid based on the patients’ complaints and independent assessment of the medical care quality in medical institutions]. Healthcare Manag. Russian. 2017;10:13–23.

- Savel’eva ZhV, Kuznetsova IB, Mukharyamova LM. Информационная доступность медицинских услуг в контексте справедливости здравоохранения [The information accessibility of medical services in the context of social justice in health care]. Kazan Med J. 2017;98(4):613–617. Russian.

- Gnatyuk OP, Amelina VI, Uryupin DA. Проблемы организации обеспечения лекарственными средствами отдельных категорий граждан Хабаровского края по результатам контрольных мероприятий и пути его улучшения [Problems of organisation of provision of drugs for certain categories of citizens of the Khabarovsk Krai in the course of control activities and methods of its improvement]. Vestnik Roszdravnadzora. 2015;5:63–68. Russian.

- Jakovljevic M, Timofeyev Y, Ekkert NV, et al. The impact of health expenditures on public health in BRICS nations. J Sport Health Sci. 2019;8(6):516–519.

- Murav’eva VN, Murav’ev AV, Khripunova AA, et al. Веб-ресурсы учреждений здравоохранения как механизм повышения доступности медицинской помощи населению [Web resources of the medical organizations as a mechanism to improve access to medical care]. Meditsinskiy Vestnik Severnogo Kavkaza. 2016;11(1):114–116.

- Bidarova FN. Практика внедрения информационной открытости контрольно-надзорных мероприятий сферы обращения лекарственных средств [Practice of information transparency introduction into supervisory actions over medicines turnover]. Bull Rus Milit Med Acad. 2018;20(1):178–181. Russian.

- Reshetnikov V, Arsentyev E, Bolevich S, et al. Analysis of the financing of Russian health care over the past 100 years. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(10):1848.

- Paschke A, Dimancesco D, Vian T, et al. Increasing transparency and accountability in national pharmaceutical systems. Bull World Health Organ. 2018;96(11):782–791.