Abstract

Objectives

To conduct a comprehensive literature review on the state of population aging, healthcare financing, and provision in India.

Methods

To obtain relevant records in the Indian context, multiple publications were searched from databases, such as Scopus, ScienceDirect, Web of Science, Medline/PubMed, JSTOR, and Google Scholar using the following keywords: “Population Ageing,” “Population Aging,” “Health System,” “Demographic Dividend,” “Non-communicable Diseases,” “Double Burden of Diseases,” “Health Spending,” “Sustainable Health Financing,” and “Health Coverage.” Data on different health indices were collected from different websites of the government of India and international organizations (e.g. World Bank, UN, WHO, and Statista).

Results

As people live longer, India faces a double burden of disease, with the rising incidence of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) amidst the presence of widespread communicable diseases. The combined problem of the double burden of diseases and population aging poses a severe sustainability challenge for its healthcare financing and the entire health system. Healthcare financing based on progressive taxation and large-scale prepayment coverage is an effective solution for sustaining the health system. However, due to the prevalence of indirect taxes, India’s tax system is regressive. Hence, community-based health insurance (CBHI) schemes can be a feasible solution to cover the large mass of poor working in the informal sector.

Conclusions

India needs to address the alterations in its healthcare needs and demands brought on by the advancing demographic shift. To achieve so, the country’s healthcare system must be reformed to accommodate strong national policies focusing on universal access to critical care especially geriatric and palliative care.

Introduction

Located in South Asia, India has the largest population in the region. Academic curiosity and wonder have always surrounded its illustrious past as ancient India, which included today’s Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka. The Republic of India at present is making headlines for its accomplishments in the social and economic domains. Due to its significant potential as emerging market economies, South Asia, and particularly India, moved up to the third position in terms of the global economy’s center of gravity after the European Union and the United States of America. After gaining independence from the British Raj, it went from having a meager per capita income of Rs. 252–255 ($3.17–$3.21)Citation1 to become the third-largest economy in the world in purchasing power parity (PPP) terms in 2021. In the 1950s, an Indian’s average lifespan was only 32 yearsCitation2 and has been raised to 70 years in 2020 given the government of India’s constant efforts and economic growthCitation3. While life expectancy is rising in India and other South Asian nations, a challenge with an aging population is taking their place. Traditionally, two processes are thought to be involved in the aging of a population: aging at the base and aging at the apex of the population. The former is due to a decrease in fertility, whereas the latter is due to a decrease in mortality among the elderlyCitation4. During the twentieth century, the combination of low fertility and low mortality resulted in substantial and rapid increases in older populations as increasingly bigger cohorts reached old age. Despite the fact that the population of this region is still quite young, population aging may soon start becoming a cause of worry for these nations as the recent rapid decrease in fertility is sure to result in an increasing proportion of the elderly in the future, which will have jeopardizing effects on national output, public health, and sustainability of both social security and health systemCitation5. Since, the elderly population is associated with high health risks due to diseases, disabilities, and low quality of lifeCitation6. These demographic shifts prompted the World Health Organization and the United Nations to declare the period 2021–2030 as the “Decade of Healthy Ageing,” a research, policy development, and outreach initiative aimed at understanding and communicating the aging experience and the needs of aging populations in the public health ecosystemCitation7.

Being home to one-sixth of the world’s population, the health of Indians has a big impact on the health of the rest of the world and being the fastest-growing developing economy, it represents the face of all developing nations in transition. The present paper reviews the status of population aging and its implication for health and health financing in India.

Methods

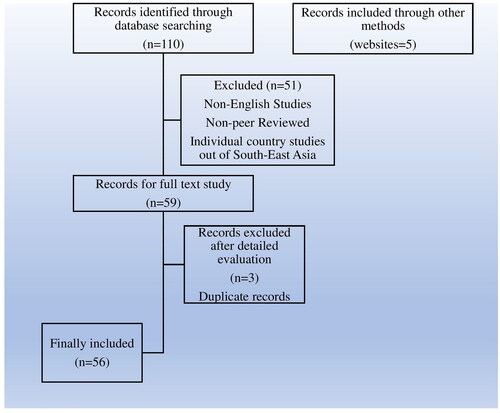

To obtain relevant records in the Indian context, multiple publications were searched from databases, such as Scopus, ScienceDirect, Web of Science, Medline/PubMed, JSTOR, and Google Scholar. To ensure broad coverage of relevant records and some government documents, the keywords selected were “Demographic Dividend,” “Non-communicable Diseases,” “Double Burden of Diseases,” “Health System,” “Health Spending,” “Sustainable Health Financing,” “Health Coverage,” and “India.” To accommodate the variation in spelling, two variants of the keyword “Population Aging” were used: “Population Aging” and “Population Ageing.” Data on different health indices were collected from different websites of the government of India and international organizations (e.g. World Bank, UN, WHO, and Statista). A total of 110 records were identified through database searches, and five records were identified through other methods, such as website searches, making a total of 115 records. From the 110 database records, 51 non-English records, non-peer-reviewed articles, and individual country studies not related to South-East Asia were excluded. Following the exclusion, a total of 59 database records remained, of which three duplicate records were dropped upon detailed evaluation. Finally, a total of 61 records—56 records from the database search along with five records from the website search were included in the review. All the above processes were performed between 14 June to 30 August 2022. shows the steps followed during the review process.

Results and discussions

Demography in India: past, present, and future

DavisCitation8 in “India’s Historical Demography” addressed Indian civilization as “a long-enduring static system in which the centuries roll by monotonously with little or no change.” Although the preceding phrase gives the impression of stagnancy, the book later explains the demographic shift the Indian subcontinent underwent from the colonial era to the creation of modern India following independence in 1947. Even the terrestrial definition of India, along with its economic and demographic structure underwent a significant transformation.

Pre-independence India experienced widespread poverty, recurrent famines (Great Bengal Famine 1770, Bihar Famine 1873, and Bengal Famine 1943), and epidemics (Cholera Outbreak 1817–1881 and 1890, Bombay Plague Epidemic 1896, and Influenza of 1918–1919) that transformed into high death rate and low life expectancy in the region. The last time India’s population decreased as a result of famine, or any calamity was in the year 1921, which is frequently referred to as the “Year of the Great Divide.” Even though the death rates were high in the following era till independence, the population remained largely stable because of the high birth rates that were in place to make up for the population that was lost. After more than three centuries as a British colony, the region finally attained sovereignty and became an independent nation in 1947. Despite the turbulent circumstances of the partition and ongoing wars, the new administration in India began simultaneous endeavors for social welfare and economic development. Several economic and welfare projects were implemented. As economic prosperity began to emerge, life expectancy increased with improvements in the nation’s health infrastructure. The growth in life expectancy in India has been slower in comparison to the other two large countries in South Asia. Bangladesh experienced the fastest growth in life expectancy followed by PakistanCitation9. Despite the slow rise in life expectancy in comparison to its neighbors, India saw a rapid increase in its population which became a cause of worry for the government due to increasing pressure on the already limited resources of the country. Family welfare initiatives and policies in India were centered on reducing fertility rates till the end of the twentieth century because the government anticipated a population explosionCitation10. Despite the efforts, India’s population was estimated to be 1.21 billion according to the preliminary census findings from 2011Citation11. The United Nations estimate shows India had 1.39 billion people in its whole population and contributed 18% of the world population as of 2019 making it the world’s second-most populous country after China. In 2027, India is predicted to overtake China as the country with the largest populationCitation12. Decades of high fertility and population growth on a plus side brought a huge percentage of the young population who had already entered or were about to enter the labor force. The demographic transition in favor of the working-age population had already started by the late 1900s, however, the transition took momentum only after 2010. While the period before 1970 saw a decline in the economically active age group aged 15–59 years, it is only during the period from 1971 to 2019, an increase was shown in the percentage of people within this age groupCitation13. The percentage of the 15–59 age group population increased from 53.08% in 1971 to 63.46% in 2019Citation12.

This demographic dividend may result in rapid economic development given the relationship between the economic life cycles and this change in the age distribution, which is likely to increase the labor supply, boost saving, and investment practicesCitation14,Citation15. However, only having favorable demography is not sufficient. The demographic dividend requires supportive institutions, high-quality education, improved health, and labor market variables to turn the increase in the population of working-age individuals into a useful economic assetCitation16–18. The East Asian miracle was largely credited to the creation of policy environments that allowed them to fully capitalize on their demographic dividendsCitation5,Citation19.

In recent decades the population rise in India has been slowing down due to falling fertility rates. In 24 states, about half of India’s population has attained the replacement fertility rate of 2.1 children per woman, which is the ideal family size when population growth slows. Albeit the national picture, state-level variations exist and are hidden by the overall picture. Scholars have examined the demographic gap between the south and other regions of the country. In 2019 lowest crude birth rate was recorded in the southern state of Kerela and the highest in the eastern state of BiharCitation13. The slowdown in population growth is news of administrative and economic delight given the low-resource setting of the country. However, with falling fertility and increased longevity comes population aging. Population aging begins as the sizable working-age cohort that generated the demographic dividend ages. India (median age of 28.4 years) is still relatively in its juvenile stage of population aging in comparison to the majority of its neighbors in East Asia and regional neighbors in South Asia like Sri Lanka (34 years). It has already aged past Bangladesh (27.6 years) which is currently the youngest nation in the regionCitation12.

India is currently second only to China relating to absolute numbers of older adults aged 60 and above, and this ranking will probably not change over the next few decades. Experts are of the opinion that even as the number of India’s aging population rises, the country’s substantial youth population will continue to fuel economic growthCitation12. Despite this, it is impossible to overlook the issue of population aging as it steadily becomes a challenge. According to the Sample Registration SystemCitation13, India’s population is increasing older rather than younger. The percentage of the 60 and above population has increased from 5.3% in 1971 to 8% in 2019 due to improvements in education, healthcare, and life expectancy. In the meantime, the percentage of “oldest old” adults 80 and older has more than doubled, it increased from 0.4% of the total population in 1950 to 0.94% in 2015, and by 2050, it is predicted to have increased to over 3%, or close to 48 million individualsCitation20. There exist regional differences in the aging profile among the states despite the headline data. For instance, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, and Jharkhand were the three youngest states, with nearly 30% of the population falling into the 0–14 age range. Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and Himachal Pradesh were the three oldest states with nearly 10% of the population falling into the above 60 age rangeCitation13. The remarkable rapidity of population aging in Asia is also one noteworthy aspect. The EU or any other conventional developed nation matured much more slowly than Asia, which is a sharp contrastCitation21–23. The cause of worry is that a majority of the developing countries in this continent will become old before they become wealthy since aging is happening more quickly than progressCitation24. For countries like India, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Nepal, it has been a serious source of concernCitation25.

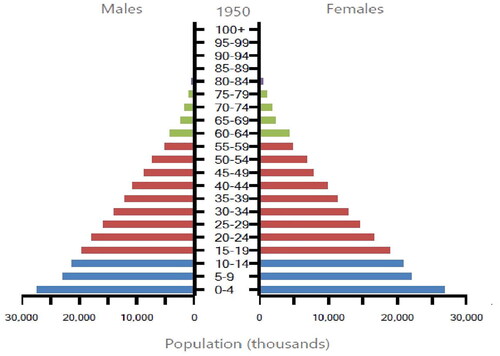

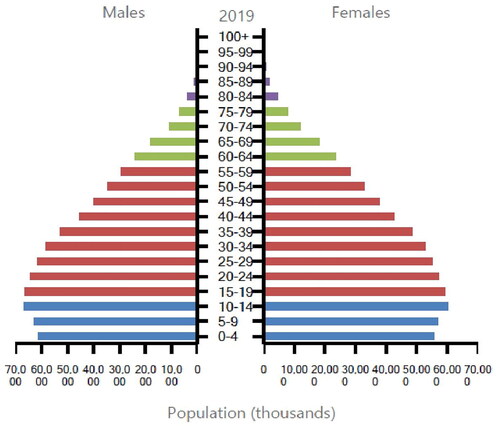

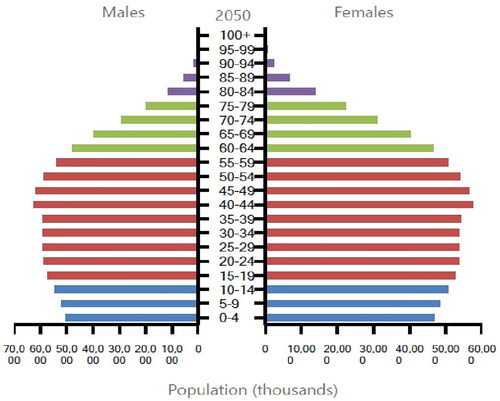

There is also the issue of “feminization of the aging population,” as women’s life expectancies rise with falling rates of maternal and female mortality. In countries like India, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh, there are already more older women than menCitation26,Citation27. The sex ratio among the older population is further expected to worsen in the future with more females outliving malesCitation12. This feminization of the aging population is becoming more of a concern since the majority of older women are widowed due to the common tendency for women to marry males older than themselvesCitation28. The majority of these widowed older women are staying alone or are less likely to remarry as they were forbidden by society from doing so, rendering them more exposed to poverty in the event that their husbands pass away and necessitating the help of social security programs. show the feminization of the aged population in India from 1950 to 2050.

Figure 2. Population distribution by sex and age group in India in 1950 (in thousands). Source: UNCitation12.

Figure 3. Population distribution by sex and age group in India in 2019 (in thousands). Source: UNCitation12.

Figure 4. Population projection by sex and age group in India for 2050 (in thousands). Source: UNCitation12.

Health in changing population landscape

India’s transition in the health sector has been remarkable. It has achieved breakthrough public health milestones by eradicating smallpox by 1977, yaws by 2004, and polio by 2014Citation29. The world is well versed in its success in reducing mortality and improving life expectancy. Once an importer of medicinal drugs, now justifiably called the “world’s pharmacy” with its success in the overseas pharmaceutical market with the help of companies like Ranbaxy and DRL. Over the past 40 years or more, the nation’s once-almost non-existent pharmaceutical industry has experienced rapid expansion and transformation, enabling it to compete on a global scale by manufacturing high-class generic medicationsCitation30–33.

However, recently with rapid demographic change, India is witnessing an increase in disease rates. As people live longer, there is an increasing incidence of disabilities, non-communicable diseases (NCDs), and the need for care for illnessesCitation27,Citation34. The epidemiological change took place with a consistent increase in the burden of NCDs. While the incidence of NCDs is increasing, the country still suffers from widespread communicable diseases, especially in its slums and rural areas. Evidence of its suffering from this “double burden of diseases” can be judged from the fact that while all five of the leading sources of disease burden in the nation in 1990 were communicable illnesses, three of the top five causes in 2016 were NCDs (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, ischemic heart disease, and cerebrovascular disease), while the other two were communicable disorders (diarrhea and lower respiratory infections)Citation35. About 5.87 million deaths in India are attributable to NCDs, which make up 60% of all fatalities. In South-East Asia, India accounts for more than two-thirds of all NCD-related deaths. Diabetes, chronic respiratory illnesses, cancer, and cardiovascular diseases are the four types of NCDs that contribute most significantly to morbidity and mortality cases from NCDsCitation36. Inter-state diversity in the epidemiological pattern makes it difficult to be generalized to the whole of India. It is crucial to comprehend the regional and economic disparities in the burden of disease while making inferences. In states with lower levels of development (Jharkhand, Rajasthan, Odisha, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Bihar, and Chhattisgarh), NCD accounts for a much smaller percentage of deaths (55%) than the higher development states (Tamil Nadu, Goa, Himachal, and Kerala), where they account for up to 72% of all fatalitiesCitation35. Chronic respiratory diseases (22%) are the leading cause of NCD mortality, followed by malignancies (12%), diabetes (5%), and cardiovascular disorders (heart disease, stroke, and hypertension) at 45% of all NCD deaths (3%). The likelihood of dying from one of the four major NCDs between the ages of 30 and 70 is 26%Citation36. This burgeoning burden of chronic illnesses among the productive age of 30–70 years can result in staggering economic losses. According to the estimates of a 2014 World Economic Forum report between 2012 and 2030, NCDs may cost India $4.3 trillion in productivity losses and healthcare costs, which is twice the nation’s annual GDPCitation34. India among the BRICS countries accounts for the second highest degree of economic loss due to cancer-related fatalities in relation to national GDPCitation37.

Briefly, the nation will certainly need to address the alterations in its healthcare needs and demands brought on by the advancing demographic shift.

Indian health system: a tail of adversities

Although India has implemented numerous changes and healthcare programs in recent decades and there has been a corresponding improvement in health indicators, in some indicators it still compares unfavorably to other low and middle income countries (LMICs)Citation38,Citation39. Basic issues with access, affordability, competency, and accountability still plague the nation’s healthcare system. State-level, rural-urban, and socioeconomic class-based health disparities are still significantCitation38. While both public and private healthcare make up the majority of the Indian healthcare system, larger reliance on the private healthcare system has made healthcare inaccessible to the underprivileged population. With the demographic and epidemiological change, India is witnessing a rise in healthcare demand and spendingCitation27,Citation40. Behera and DashCitation41 studied the relationship between population aging and health expenditure. They found that a 1% increment in the share of the aged population to the total population, leads to a 0.06% change in government expenditure on health. In countries like Japan where population aging is already in an advanced stage, healthcare spending per person is almost four times greater for those 65 and older than for the general populationCitation9.

While health expenditure as a share of GDP rising rapidly, the government’s share is still negligible with a high share of out-of-pocket expenditure making India’s healthcare financing system regressiveCitation41–43. A significant proportion of the population in India is unable to access healthcare due to financial barriers and a majority of them get pushed into poverty every year by paying for medical servicesCitation38,Citation44,Citation45. JakovljevicCitation46 projected future health expenditure for BRICS countries. India is predicted to have the greatest out-of-pocket spending shares in 2030 with 55.7%. Even though the government has implemented various schemes to subsidize the health expenditure for the poor, these schemes are most often seen as ineffective as the poorest 20% of the population only receive 10% of available subsidies, while the richest 20% receive 33% of themCitation47.

While the rise in health difficulties affecting the elderly population has come to the attention of the government and medical professionals, high health spending among the elderly coupled with the absence of insurance coverage exposes the elderly—particularly those belonging to lower socio-economic strata—to great financial riskCitation27. The family system is the key source of funding for healthcare for the majority of older Indians. However, both out-of-pocket spending and family as a source of health spending for them are insufficient and unsustainableCitation26. This brings the debate of “who pays” and “how” to the forefront. The current health system in India provides limited financial protection and coverage of prepayment schemes to its peopleCitation41. The social security system for the elderly is not well developed and there is no separate health program for the aged populationCitation26. Increasing social security needs due to the aging of young India, the economic slowdown that the country is going through since the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, and increasing healthcare demand due to the rise in disease burden will put a strain on the sustainability of financing sourcesCitation48,Citation49. The pandemic outbreak brought the worst public health disaster; the nation has ever experienced as a result of the deficiencies in the healthcare systemCitation39. The elderly particularly experienced severe health and food-security difficulties at the onset of the lockdown in March 2020Citation50. The changing population needs must be addressed effectively to achieve healthful living for every Indian.

The way forward: the quest for a sustainable health financing system

A discussion on “sustainable healthcare finance” was first started in 2013 by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) at an EU-level summit titled “sustainable healthcare.”Citation48 Sustainable healthcare finance is concerned with both raising additional funds for health and maximizing the use of already available financesCitation51. Even among the richest countries, the combined problem arising from the double burden of diseases and population aging poses a severe sustainability challengeCitation52. Catastrophic household health expenditure from out-of-pocket spending on the rising NCDs might push nearly 150 million individuals into poverty worldwideCitation53.

Evidence has shown healthcare financing based on progressive taxation and large-scale prepayment coverage is an effective solution for sustaining the health systemCitation48. As a result, one of the objectives of healthcare finance should be to increase the contribution of public prepayment programs like progressive taxation or social health insurance (SHI) and decrease out-of-pocket (OOP) payments. It is highly challenging for the SHI alone to attain universal healthcare coverage (UHC) due to a sizable informal sector and a sizable population living below the poverty line in India. This leaves us with the choice of taxes. Albeit health financing based on progressive taxation is more sustainable than SHI, the function of income tax is quite minimal, as the tax system mainly relies on regressive indirect taxes (consumption taxes) and there are significant tax evasions. Community-based health insurance (CBHI) schemes can be a feasible solution to cover India’s large mass of poor working in the informal sector. It is a non-profit insurance coverage system that involves community involvement and targets the informal sector in developing nations. Under this insurance system, community members usually pool funds among themselves to cover the cost of healthcare. The advantages of CBHI include its potential for future expansion into more extensive financing arrangements which will also be able to cover India’s huge informal sector, its ability to meet community needs, and its increased knowledge of prepaid and insurance financing options. But CBHI also has a lot of difficulties in the form of low enrolment resulting in insufficient risk sharing and weak financial stability due to the majority of its contributors being poorCitation44. Both the federal and state governments should put more effort to provide necessary funds to such CBHIs in order to encourage their growth, if accepted and practiced widely these schemes can protect the Indian poor from regressive health financing options.

Population aging in public health policy framework

No health system change is likely to be implemented successfully on its own. The majority of reforms are interconnected and need to be implemented alongside reforms in other aspects of the health systemCitation54. NCDs and communicable diseases, both considerably increase disease burden and death rates in India and there are disparities in their prevalence at various phases of life, geographies, and across various social and economic groupingsCitation35. To reduce the inequity priority should be given to health in the concurrent list. To improve the capability of the healthcare system and health financing in India, a coordinated strategy must be established at the national levelCitation39,Citation55. To enhance the efficiency of the public sector and reduce the pressure from the national budget, effective PPP models which are already successful in various Indian states should be implemented at a national level. These models include including infrastructure subsidies for the opening of super-specialized hospitals, the transfer of management responsibility of primary health centers to NGOs, the adoption of local primary health centers or sub-centers by industry, the adoption of villages for the improvement of health by industrial corporate houses, and the encouragement and mobilization of patients to form health action associationsCitation38,Citation47.

Strong national policies that emphasize prevention and universal access to necessary treatments are also required, and they must be developed and put into action. The government of India (GoI) launched the National Programme for Health Care of the Elderly (NPHCE) in 2011 with the vision to: (1) provide accessible, affordable, and good quality long-term, comprehensive, and dedicated care services to an aging population; (2) construct a new “architecture” for aging; (3) build a framework to create an enabling environment for “a Society for all Ages,” and (4) To promote the concept of “Active and Healthy Aging.”Citation56 However, the success of NPHCE in achieving its vision has been limitedCitation57. Recently, the National Health Policy 2017 by the GoI has endorsed the goal of providing universal access to high-quality healthcare services for individuals of all ages without causing financial hardship to anyone. The program advised the commencement of Ayushman Bharat, the government of India’s flagship program, to realize the goal of Universal Health Coverage (UHC). Under the Ayushman Bharat scheme, PM-JAY is the world’s largest health assurance program, which aims to cover both secondary and tertiary care hospitalization for over 107.4 million vulnerable and poor families, who represent the poorest 40% of the Indian population, with a health benefit of Rs. 5 lakhs per family per yearCitation58. Health and Wellness Centers (AB-HWCs) are also planned under the program to provide comprehensive care, including geriatric and palliative careCitation59. However, the nation’s public health aspirations for its rapidly aging population should be backed by an effective implementation system to be materializedCitation60,Citation61.

Conclusions

In India, population aging is inevitable, and the government is now unprepared to meet the rising and changing requirements of aged people. This demographic phenomenon will have significant policy concerns, to which the country must begin to adapt. The country needs to address the alterations in its healthcare needs and demands brought on by the advancing demographic shift. To achieve so, the country’s health system must be reformed to accommodate strong national policies focusing on prevention and universal access to critical care especially geriatric and palliative care. With its sizable youth population, the nation must also concentrate on providing them with improved health facilities to benefit from the widely discussed demographic dividend. India needs to choose between an unsustainable GDP-driven economy in which economic growth prevails at the expense of an unhealthy population or a health-driven economy that is more sustainable.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This work was not funded by any funding agency.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

The authors declare that they have no known competing interests for this work.

Author contributions

All authors PMS, HSR, and MMJ were major contributors to writing this paper. PMS and HSR reviewed the articles and prepared the first draft of the manuscript. MMJ developed the idea, supervised the workflow, and revised the manuscript draft for important intellectual content. All three authors analyzed the contents and participated in writing the paper fulfilling ICMJE rules for full authorship.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

The Editor in Chief helped with adjudicating the final decision on this paper.

Consent for publication

The final version of the manuscript for submission was approved by all authors.

Acknowledgements

The authors are very much thankful to the three anonymous reviewers and the editorial team of the Journal of Medical Economics for their valuable comments and suggestions.

References

- Raychaudhuri GS. On some estimates of national income: Indian economy 1858–1947. Econ Polit Wkly. 1996;1(16):673–679.

- Statista [Internet]. Life expectancy (from birth) in India from 1800 to 2020; 2022 [cited 2022 Jul 25]. Available from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1041383/life-expectancy-india-all-time/

- World Bank [Internet]. Washington (DC): The World Bank. 2022 [cited 2022 Jul 19]. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/country/IN

- Chanana HB, Talwar PP. Aging in India: its socioeconomic and health implications. Asia Pac Popul J. 1987;2(3):23–38.

- Lee S, Mason A, Park D. Why does population aging matter so much for Asia? Population aging, economic growth, and economic security in Asia. Manila: Asian Development Bank; 2011. (ADB Economics Working Paper Series; Report number 284).

- Irshad CV, Dash U. Healthy aging in India: evidence from a panel study. JHR. 2022;36(4):714–724.

- Thiyagarajan JA, Mikton C, Harwood RH, et al. The UN decade of healthy ageing: strengthening measurement for monitoring health and wellbeing of older people. Age Ageing. 2022;51:1–5.

- Davis K. Foreward. New York (NY): Routledge Library; 2022. p. viii.

- Bloom D, Canning D, Rosenberg L. Demographic change and economic growth in South Asia. Cambridge (MA): Harvard School of Public Health; 2011. (Program on the Global Demography of Aging; PGDA Working Paper No. 67).

- Ram U, Ram F. Demographic transition in India: insights into population growth, composition, and its major drivers. Glob Public Health. 2021. DOI:10.1093/acrefore/9780190632366.013.223

- Census India [Internet]. New Delhi: Government of India; 2011 [cited 2022 Aug 3]. Available from: https://censusindia.gov.in/census.website/

- UN. World population prospect. Washington (DC): United Nations: Population Division; 2019.

- Registrar General of India [Internet]. New Delhi: Government of India; 2022 [cited 2022 Jul 25]. Available from: https://censusindia.gov.in/census.website/node/294

- Mason A. Demographic transition and demographic dividends in developed and developing countries. United Nations Expert Group Meeting on Social and Economic Implications of Changing Population Aging Structure; 2005 Aug 31; Mexico.

- Ladusingh L, Narayana MR. Chapter 7, aging, economic growth, and old-age security in Asia. In: Demographic dividends for India: evidence and implications based on national transfer accounts. Cheltenham, UK; MA, USA; Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd.; 2012. p. 203–230.

- Golley J, Tyers R. Demographic dividends, dependencies, and economic growth in China and India. Asian Econ Pap. 2012;11(3):1–26.

- Mason A, Lee R, Abrigo M, et al. Support ratios and demographic dividends: estimates for the world. New York (NY): United Nations Population Division; 2017. (Technical Paper No. 2017/1).

- Nagar P, Dhawan A. Economic advantages of demographic dividend: the case for India. Int J Sci Basic Appl Res. 2018;8(6):1230–1241.

- Navaneetham K, Dharmalingam A. Age structural transitions, demographic dividends and millennium development goals in South Asia: opportunities and challenges. XXVI IUSSP International Population Conference; 2009; Morocco.

- Agarwal A, Lubet A, Mitgang E, et al. Chapter 9, population change and the impact in Asia and the Pacific. In: Population aging in India: facts, issues, and options. Tokyo: Springer; 2020. p. 201–220.

- Jakovljevic M. The aging of Europe. The unexplored potential. Farmeconomia. 2015;16(4):89–92.

- Jakovljevic MM, Netz Y, Buttigieg SC, et al. Population aging and migration – history and UN forecasts in the EU-28 and its east and south near neighborhood – one century perspective 1950–2050. Glob Health. 2018;14(30):1–6.

- Balachandran A, de-Beer J, James KS, et al. Comparison of population aging in Europe and Asia using a time-consistent and comparative aging measure. J Aging Health. 2020;32(5–6):340–351.

- Srivastavaa A, Saikia N. Aging in India: comparison of conventional and prospective measures, 2011. medRxiv. 2022:1–25.

- Marois G, Zhelenkova E, Ali B. Labour force projections in India until 2060 and implications for the demographic dividend. Soc Indic Res. 2022;164(1):477–497.

- Rajan S. Implications of population aging with special focus on social protection for elderly persons in South Asia. Indian J Hum Dev. 2008;2(1):203–221.

- Sahoo H, Govil D, James K, et al. Health issues, health care utilization and health care expenditure among elderly in India: thematic review of literature. Aging Health Res. 2021;1(2):100012–100017.

- Rajan S. Population aging and health in India. Mumbai: Centre for Enquiry into Health and Allied Themes (CEHAT); 2006 [cited 2022 Jul 28]. Available from: https://www.cehat.org/cehat/uploads/files/ageing(1).pdf

- WHO [Internet]. Feature stories: India; 2021 [cited 2022 Jul 20]. Available from: https://www.who.int/india/news/feature-stories/detail/a-push-to-vaccinate-every-child-everywhere-ended-polio-in-india#:∼:text=Within%20two%20decades%2C%20India%20received,Bengal%20on%2013%20January%202011

- Smith R, Correa C, Oh C. Trade, TRIPS, and pharmaceuticals. Lancet. 2009;373(9664):684–691.

- Kedron P, Bagchi-Sen P. US market entry processes of emerging multinationals: a case of Indian pharmaceuticals. Appl Geogr. 2011;31(2):721–730.

- Mohiuddin M, Mazumder M, Chrysostome E, et al. Relocating high-tech industries to emerging markets: case of pharmaceutical industry outsourcing to India. Transnatl Corp Rev. 2017;9(3):201–217.

- Jakovljevic M, Liu Y, Cerda Y, et al. The global south political economy of health financing and spending landscape – history and presence. J Med Econ. 2021;24(sup1):25–33.

- Bloom DE, Sekher TV, Lee J. Longitudinal aging study in India (LASI): new data resources for addressing aging in India. Nat Aging. 2021;1(12):1070–1072.

- Kluwer W. Communicable or noncommunicable diseases? Building strong primary health care systems to address the double burden of disease in India. J Family Med Prim Care. 2019;8(2):326–329.

- WHO. Burden of NCDs and their risk factors in India. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014.

- Romaniuk P, Poznanska A, Brukało K, et al. Health system outcomes in BRICS countries and their association with the economic context. Front Public Health. 2020;8:80.

- Patel V, Parikh R, Nandraj S, et al. Assuring health coverage for all in India. Lancet. 2015;386(10011):2422–2435.

- Mallya P. Health in India: need for a paradigm shift. Procedia Soc. 2012;37:111–122.

- Jakovljevic M. Comparison of historical medical spending patterns among the BRICS and G7. J Med Econ. 2016;19(1):70–76.

- Behera D, Dash U. Healthcare financing in south-east Asia: does fiscal capacity matter? Int J Healthc Manag. 2018;13(1):375–384.

- Pradhan J, Dwivedi R, Pati S, et al. Does spending matters? Re-looking into various covariates associated with out of pocket expenditure (OOPE) and catastrophic spending on the accidental injury from NSSO 71st round data. Health Econ Rev. 2017;7(1):48.

- Rout S, Choudhury S. Does public health system provide adequate financial risk protection to its clients? Out of pocket expenditure on inpatient care at secondary level public health institutions: causes and determinants in an eastern Indian state. Int J Health Plan Manage. 2018;33(2):1–12.

- Kwon S. Health care financing in Asia: key issues and challenges. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2011;23(5):651–661.

- Marten R, McIntyre D, Travassos C, et al. An assessment of progress towards universal health coverage in Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa (BRICS). Lancet. 2014;384(9960):2164–2171.

- Jakovljevic M, Lamnisos D, Westerman R, et al. Future health spending forecast in leading emerging BRICS markets in 2030: health policy implications. Health Res Policy Syst. 2022;20(23):1–14.

- Younger D. Health care in India. Neurol Clin. 2016;34(4):1103–1114.

- Liaropoulos L, Goranitis I. Health care financing and the sustainability of health systems. Int J Equity Health. 2015;14:80.

- Gauttam P, Patel P, Singh B, et al. Public health policy of India and COVID-19: diagnosis and prognosis of the combating response. Sustain. 2021;13(6):3415–3418.

- Duflo E, Banerjee A, Schilbach F, et al. Aging and health in India: a longitudinal study and an experimental platform. Cambridge, MA: Jameel Abdul Lateef Poverty Action Lab; 2022.

- Jakovljevic MB. Resource allocation strategies in southeastern European health policy. Eur J Health Econ. 2013;14(2):153–159.

- Rath S, Yu P, Srinivas S. Challenges of non-communicable diseases and sustainable development of China and India. Acta Ecol Sin. 2018;38(2):117–125.

- Jakovljevic M, Jakab M, Gerdtham U, et al. Comparative financing analysis and political economy of noncommunicable diseases. J Med Econ. 2019;22(8):722–727.

- Beattie A. EDI health policy seminar. Johannesburg: World Bank; 1998.

- Rout HS. Socio-economic factors and household health expenditure: the case of Orissa. J Health Manag. 2008;10(1):101–118.

- Verma R, Khanna P. National program of health-care for the elderly in India: a hope for healthy ageing. Int J Prev Med. 2013;4(10):1103–1107.

- Mathur A. Ageing issues in India: practices, perspectives and policies. In: Geriatric practice: its status in India. Singapore: Springer; 2022. p. 157–170.

- National Health Authority [Internet]. Government of India; 2017 [cited 2022 Jul 30]. Available from: https://nha.gov.in/PM-JAY

- Goel A, Kaur A. The state of elderly in India: life and challenges in the decade of healthy aging. Indian J Public Health. 2022;66(1):1–2.

- Jakovljevic M, Sugahara T, Timofeyev Y, et al. Predictors of (in)efficiencies of healthcare expenditure among the leading Asian economies – comparison of OECD and Non-OECD nations. Risk Manag Healthc Policy; 2020;13:2261–2280.

- Ranabhat CL, Jakovljevic M, Dhimal M, et al. Structural factors responsible for universal health coverage in low- and middle-income countries: results from 118 countries. Front Public Health. 2020;7:414.