Abstract

Background

Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) is associated with poor prognosis. Healthcare-related management likely presents a substantial economic burden associated with time away from work in patients with CCA.

Objectives

To assess productivity loss, associated indirect costs, and all-cause healthcare resource utilization and costs owing to workplace absenteeism, short-term disability, and long-term disability in CCA patients with work absence and disability benefits eligibility in the United States.

Methods

US retrospective claims data from Merative MarketScan Commercial and Health and Productivity Management Databases. Eligible patients were adults with ≥1 non-diagnostic medical claim for CCA in the index period (1 January 2011–31 December 2019) and had ≥6 months of continuous medical and pharmacy benefit enrolment before and ≥1 month of follow-up and full-time employee work absence and disability benefits eligibility after the index date. Outcomes were assessed in patients with CCA, intrahepatic CCA (iCCA), and extrahepatic CCA (eCCA) in absenteeism, short-term disability, and long-term disability cohorts (measured per patient per month [PPPM] for a month of 21 workdays), with costs standardized to 2019 USD.

Results

One thousand and sixty-five patients with CCA were included (iCCA: n = 624 [58.6%]; eCCA: n = 380 [35.7%]). The mean age was 51.9–53.9 years across cohorts. In patients with iCCA and eCCA, respectively, the number of mean all-cause days absent PPPM for illness was 6.0 and 4.3, and 12.9 and 6.6% had ≥1 CCA-related short-term disability claim. Median indirect costs PPPM owing to absenteeism, short-term disability, and long-term disability, respectively, in patients with iCCA were $622, $635, and $690, and $304, $589, and $465 in patients with eCCA. Patients with iCCA vs. eCCA had higher inpatient, outpatient medical, outpatient pharmacy, and all-cause healthcare costs PPPM.

Conclusions

Patients with CCA had high productivity losses, indirect costs, and medical costs. Outpatient services costs contributed greatly to the higher healthcare expenditure observed in patients with iCCA vs. eCCA.

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY

Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) changes patients’ health, lives, finances, and work. We wanted to understand the effect of CCA on work, costs of lost workdays, and costs of healthcare for patients in the US. We looked at health insurance claims for 1,065 adults which included payments requested to insurance providers for covered healthcare from 2011 to 2019. We grouped people in three ways. The “absence group” included 107 people whose work absences we could track. The “short-term leave” (STL) group included 617 people whose jobs allowed short-term medical leave benefits. The “long-term leave” (LTL) group included 549 people whose jobs allowed long-term medical leave benefits. People could belong to more than one group, i.e. a person who had an absence could also take STL or LTL. About two thirds of the employees with CCA in the absence group missed at least 1 day of work because of illness and lost more than 5 workdays per month on average. Work lost for all absences generally costs employers almost $1000 per month. About half of the STL group took short-term leaves. On average, they lost 6–7 workdays per month, costing about $860. About one-tenth of the LTL group took long-term leaves. On average, they lost just over 6 workdays per month, costing about $800. Average total healthcare costs for all groups were about $10,300–$11,200 per month. Overall, people with CCA inside the liver missed more days from work because of illness and had higher total healthcare costs compared to those with CCA outside the liver.

Introduction

Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) is an aggressive cancer of the bile duct affecting working age patients which often presents at an advanced stage and is associated with a poor prognosisCitation1. CCA is the second most common type of primary liver cancer after hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)Citation1. CCA can be classified as intrahepatic CCA (iCCA) which arises above the second-order bile ducts and extrahepatic CCA (eCCA), encompassing perihilar and distal CCACitation1. The estimated 5-year mortality rate of CCA in the United States is 80.1%Citation2.

From 1997 to 2012, the frequency of discharges of patients in the United States with CCA per 100,000 admissions increased from 5.6 to 7.8 in patients 18–44 years of age, and from 40.5 to 43.0 in patients 45–64 years of age.Citation3 Based on Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) data from CCA diagnoses in the United States, 33.0% of patients with CCA were <65 years of age at diagnosis; the age-adjusted incidence rates of CCA generally increased between 2001 and 2017 in patients 18–44 and 45–64 years of ageCitation2, indicating an increase in the incidence of working-age patients with CCA. Moreover, costs are higher for these patients. A retrospective claims-based study in the United States found that costs related to previously treated advanced CCA were greater for patients younger than 65 years of age than patients 65 years of age and olderCitation4. Healthcare-related management, including systemic and surgical treatment, and palliative measures, such as radiation therapy or stenting procedures that may improve quality of life, is likely to increase the time away from work and to have a notable economic effect on these patients. There is a paucity of data on the economic burden of CCA, especially in working-age patients. To address this aspect of disease burden, the effects of CCA on work and productivity loss for patients need to be understood.

This study assessed the productivity loss and indirect costs associated with workplace absenteeism, short-term disability, and long-term disability among patients with CCA with work absence and disability benefit eligibility. All-cause healthcare resource utilization and costs from a US commercial insurance perspective were also assessed among patients with CCA.

Methods

Study design

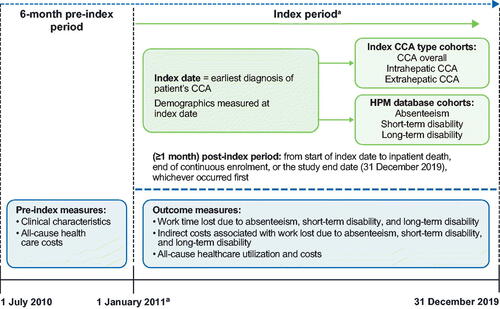

This retrospective cohort study used administrative claims data from the Merative MarketScan Commercial Database and the Merative MarketScan Health and Productivity Management Database between 1 July 2010 and 31 December 2019, so that the most recently available data for patients with CCA were used at the time of the study. The Merative MarketScan Commercial Database contains drug and medical data from health plans and employers for employees covered by employer-sponsored private health insurance in the United StatesCitation5,Citation6. The Health and Productivity Management Database contains data on workplace absence, short-term and long-term disability, and workers’ compensation with medical or surgical claims and outpatient drug data, with direct and indirect costs associated with a particular treatment or conditionCitation5,Citation6.

The study design consisted of a 6-month pre-index period and at least a 1-month follow-up period post-index date (). The index date was the date of earliest CCA diagnosis between 1 January 2011 and 1 December 2019. The follow-up period was initiated from the index date and extended through inpatient death, disenrolment, or study end date (31 December 2019), whichever occurred first.

Patient eligibility

Patients were men or women 18 years of age and older with one or more non-diagnostic medical claims with an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth or Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification diagnosis code (ICD-9-CM/ICD-10-CM; iCCA: 155.1/C22.1; eCCA: 156.1, 156.9/C24.0, C24.9) for CCA between 1 January 2011 and 31 December 2019; had continuous enrolment and full-time employee eligibility in the Health and Productivity Management Database at least 1 month after the index date; and had a continuous enrolment in medical and pharmacy benefits from at least 6 months before the index date and at least 1 month after the index date. Patients were excluded from the analysis if they had a diagnosis of cancer of overlapping sites of the biliary tract (ICD-9-CM: 156.8 or ICD-10-CM: C24.8) or a diagnosis of gallbladder cancers (ICD-9-CM: 156.0 or ICD-10-CM: C23.0) during the study.

Study outcomes and analyses

Patients were grouped by diagnosis (CCA, iCCA, or eCCA). Productivity losses, associated indirect costs, and all-cause healthcare resource utilization and costs were reported among three productivity loss cohorts: absenteeism, short-term disability, and long-term disability.

The absenteeism cohort included employees for which employers contributed the payroll information necessary to determine days missed from work. Descriptive analyses were performed on the subset that had one or more days absent from work for any reason or for illness. Annual indirect costs for absenteeism were derived by multiplying the number of workdays lost by the mean daily wage, which was determined for each patient based on age, sex, and region using the 2019 Labor Statistics/Bureau of the Census Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic SupplementCitation7.

The short-term disability and long-term disability cohorts included patients known to be eligible for short-term or long-term disability leave, respectively. These cohorts were comprised of those who were employed by employers who contributed this data type to the database, including those who did and did not utilize this benefit. One aim of this study was to determine the proportion of patients who did use this leave benefit, and therefore, the denominator used was all employers for whom this disability information was available. Descriptive analyses were performed on the subset that had one or more claims for disability leave for any reason or for CCA. Annual indirect costs of disability were derived by multiplying the number of days lost by the mean daily wage and then a 70% wage adjustment, which is standard for work disability benefitsCitation8.

Healthcare costs were estimated based on inpatient admissions, outpatient medical services, and outpatient pharmacy costs. Costs were based on paid amounts of adjudicated claims, including insurer and health plan payments as well as the patient-paid portion (i.e. copayment, deductible, and coinsurance). All productivity loss outcomes and costs were assessed and estimated per patient per month (PPPM) during the post-index period, defined using a month of 21 workdays. Costs were adjusted for inflation using the Consumer Price Index and standardized to 2019 US dollarsCitation9. Data in this manuscript are presented using descriptive statistics, and no formal statistical testing was conducted for differences between cohorts. Data were analyzed using World Programming System Analytics software.

Results

Patient disposition

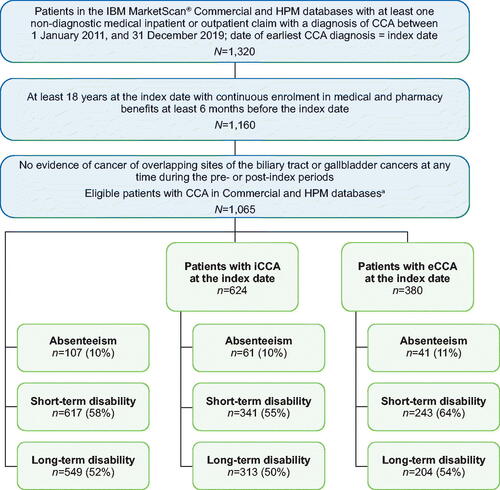

Overall, 1,065 patients (iCCA: n = 624 [58.6%]; eCCA: n = 380 [35.7%]) met all eligibility criteria and were included in the analysis (). The numbers of eligible patients with CCA with evidence of work absence and disability eligibility benefits for analysis in absenteeism, short-term disability, and long-term disability were 107, 617, and 549, respectively.

Figure 2. Patient cohorts. Patients with evidence of work absence and disability benefits eligibility for analysis in each cohort in patients with CCA, iCCA, and eCCA were full-time employees with ≥1-month post-index enrolment in the HPM and Commercial databases. aPatients with CCA include patients with iCCA, eCCA, or both. In the overall HPM sample, 61 patients had diagnoses for both iCCA and eCCA and were not included in the subsequent iCCA and eCCA cohorts. Abbreviations. CCA, cholangiocarcinoma; eCCA, extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma; HPM, health and productivity management; iCCA, intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma.

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics

The mean ages of patients were similar across all cohorts (). There were more men (range: 61–85% across cohorts) than women in each cohort (range: 15–39%), with most patients residing in the southern United States (29.5–41.3%). The most common insurance type in each cohort was an exclusive provider organization or preferred provider organization ().

Table 1. Baseline demographics and characteristics.

The mean Deyo-Charlson Comorbidity Index score across cohorts was higher in patients with iCCA (range: 4.2–4.4) compared with patients with eCCA (range: 3.3–3.5; ). The most frequently reported comorbidities across all cohorts were pain (64–74%), any malignancy excluding CCA, gallbladder/biliary tract, and cancers involving the skin (51–67%), and moderate or severe liver disease (49–72%) (Supplementary Figure S1). Among the patients with moderate or severe liver disease, hepatitis C virus was present in more patients with iCCA than eCCA in all cohorts: absenteeism (15 vs. 5%), short-term disability (15 vs. 7%), and long-term disability (13 vs. 7%). Non-alcoholic cirrhosis was also present in more of these patients who had iCCA compared with eCCA: absenteeism (26 vs. 10%), short-term disability (19 vs. 8%), and long-term disability (18 vs. 7%).

Absenteeism

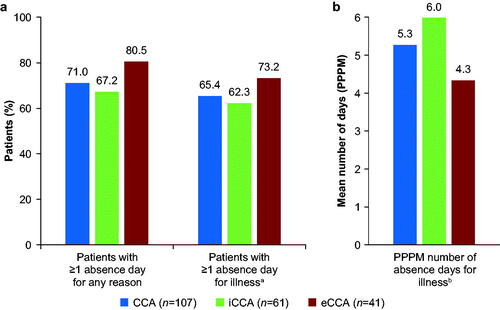

In the absenteeism cohort, the mean (standard deviation) duration of follow-up in days was 725.0 (730.4) for CCA, 732.0 (729.4) for iCCA, and 751.5 (772.4) for eCCA. Seventy-six patients (71.0%) with CCA had one or more absence days for any reason (). The percentage of patients with iCCA who had one or more absence days for any reason (67.2%) was lower than for patients with eCCA (80.5%). Seventy patients (65.4%) with CCA had one or more absence days for illness (iCCA: 62.3%; eCCA: 73.2%). The number of mean days absent for illness PPPM was higher for patients with iCCA (6.0) than for those with eCCA (4.3) ().

Figure 3. Patients with CCA with one or more absence days during follow-up. (a) Percentage of patients with CCA with one or more absence days during follow-up for any reason or for illness, and (b) the mean number of absence days for illness PPPM. aNot all employers report a specific reason for sick time; reasons included disability, medical leave act, and sick leave. bAmong the subset with one or more absence days for illness (i.e. the mean does not include employees with 0 illness days). Abbreviations. CCA, cholangiocarcinoma; eCCA, extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma; iCCA, intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma; PPPM, per patient per month.

Short-term disability

For patients with short-term disability eligibility, the percentage with one or more short-term disability claims for any reason was similar for iCCA (48.7%) and eCCA (49.4%) (). Among all patients with CCA who used short-term disability benefits for any reason, the mean time to first claim was 71.4 days from the index date, with a mean of 6.7 claim days PPPM. A higher percentage of patients with iCCA (12.9%) than eCCA (6.6%) had one or more short-term disability claims owing to CCA, and the mean number of days PPPM on short-term disability owing to CCA was higher for patients with iCCA (6.5 days) than eCCA (4.3 days). Among patients with short-term disability claims for any reason, 23 patients (13.9%) with iCCA and 20 patients (16.7%) with eCCA also had a long-term disability claim.

Table 2. Patients with one or more short-term disability or long-term disability claims during follow-up.

Long-term disability

Among patients with long-term disability eligibility, 9.5% (iCCA: 8.9%; eCCA: 11.8%) had one or more long-term disability claims for any reason (). Among patients who used long-term disability benefits for any reason, the mean time to claim was 271.8 days from the index date, with a mean use of 6.2 days PPPM. The percentage of patients who had one or more long-term disability claims owing to CCA was similar between patients with iCCA (2.6%) and eCCA (2.9%). Patients with iCCA had a notably shorter time to their first long-term disability claim for any reason than patients with eCCA (187.7 vs. 369.9 days). Patients with iCCA and eCCA had similar long-term disability duration for any reason (6.2 and 6.3 days PPPM, respectively).

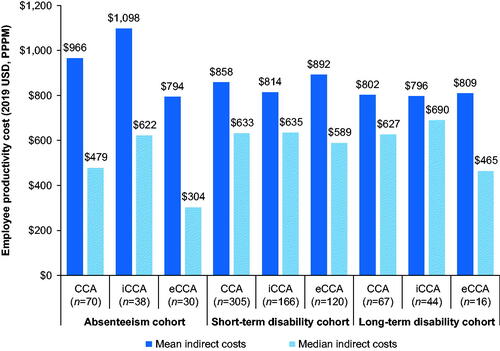

Indirect and all-cause costs

In the absenteeism cohort, patients with iCCA had higher mean and median employee productivity costs PPPM than those with eCCA (). In the short-term disability eligibility cohort, indirect costs were more similar between iCCA and eCCA. In the long-term disability eligibility cohort, patients with iCCA had similar mean indirect costs PPPM compared with patients with eCCA, but higher median indirect costs PPPM. In the absenteeism, short-term disability, and long-term disability cohorts, respectively, mean indirect costs associated with productivity loss contributed to 8.6, 7.2, and 6.7% of the total costs ($11,287, $11,887, and $11,977).

Figure 4. Employee productivity costs during follow-up. Abbreviations. CCA, cholangiocarcinoma; eCCA, extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma; iCCA, intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma; PPPM, per patient per month.

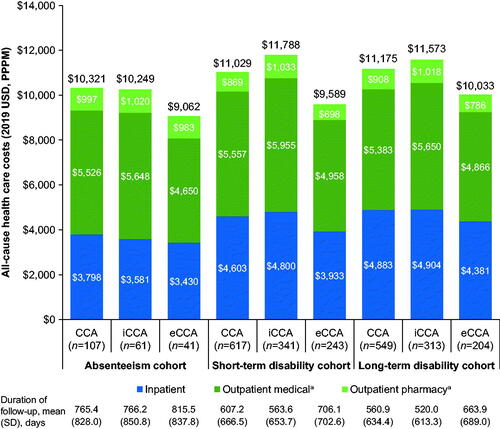

Mean all-cause healthcare costs PPPM during the follow-up period were higher among patients with iCCA compared with those with eCCA across all cohorts (). Costs associated with outpatient services were the highest contributor to total costs. The percentage of patients with CCA, iCCA, or eCCA being admitted to the hospital were similar across each cohort of absenteeism (75.7, 72.1, and 78.0%, respectively), short-term disability (75.9, 73.9, and 75.3%, respectively), and long-term disability (73.8, 71.2, and 74.5%, respectively). The percentage of patients with CCA, iCCA, or eCCA experiencing emergency department visits were also similar across each cohort of absenteeism (58.9, 59.0, and 58.5%, respectively), short-term disability (54.3, 54.0, and 54.3%, respectively), and long-term disability (52.6, 50.8, and 55.4%, respectively).

Figure 5. Mean all-cause healthcare costs during follow-up. aOutpatient pharmacy services do not include therapies administered in an office setting; infusion therapies administered in an office setting are reflected in the outpatient medical services. Outpatient medical services also include emergency department visits, outpatient office visits, and other outpatient services. Abbreviations. CCA, cholangiocarcinoma; eCCA, extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma; iCCA, intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma; PPPM, per patient per month; SD, standard deviation.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first retrospective cohort study to assess the effect of CCA on productivity loss owing to workplace absenteeism, short-term disability, and long-term disability, and to present the associated indirect costs and direct all-cause healthcare costs and health resource utilization in patients with CCA, iCCA, and eCCA in the United States. Compared with patients with eCCA, a higher percentage of patients with iCCA had one or more short-term disability claims owing to CCA, with a higher mean number of short-term disability days PPPM. A similar percentage of patients with iCCA and eCCA had one or more long-term disability claims owing to CCA. The mean durations of follow-up were generally comparable between the short-term disability and long-term disability claim groups, as well as between patients with iCCA and eCCA within each group. The mean number of days from the index date to the first long-term disability claim in patients with iCCA (188 days) was substantially shorter than in patients with eCCA (370 days). Among patients with work absence claims, patients with iCCA compared with eCCA had a higher number of mean days PPPM for illness-related absences, higher related mean indirect costs PPPM, and higher mean all-cause total healthcare costs PPPM, the biggest driver of which was outpatient services. Higher healthcare expenditure may, in part, be related to the greater mean comorbidity score among patients with iCCA.

The higher productivity loss and costs in patients with iCCA vs. eCCA may, in part, reflect differences in the clinical or symptomatic presentation that result in greater symptom burden in patients with iCCA vs. eCCA. Because of its anatomic location, iCCA is typically not associated with symptoms of biliary tract obstruction, whereas patients with eCCA often initially present with jaundiceCitation10. Instead, iCCA is usually asymptomatic during early stages and often has a late presentation with non-specific symptoms seen in advanced disease, such as abdominal pain, weight loss, fever, anorexia, asthenia, fatigue, malaise, and nausea, with jaundice being less frequentCitation1,Citation10,Citation11. Based on these differences in symptomology, it has been suggested that eCCA (specifically perihilar CCA) may be diagnosed earlier and when smaller in size compared with iCCACitation12. Taken together, these observations along with the higher comorbidity score in patients with iCCA, suggest that iCCA may have a higher burden of illness that could make it more challenging for patients to work. Further studies would be needed to assess the differences between iCCA and eCCA in terms of the impact of symptom burden on associated productivity loss and costs.

Direct comparisons between the present findings and those of previous studies are rendered difficult by differences in the databases, patient populations, and timeframes used. A retrospective claims analysis conducted using Optum’s de-identified Clinformatics Data Mart Database from 2007 to 2019 reported substantial healthcare costs in 1,298 patients in the United States with previously treated advanced CCA, with reported mean all-cause healthcare costs of $14,403 and inpatient costs of $6,523 PPPM (standardized to 2019 US dollars)Citation4. Higher mean all-cause healthcare costs PPPM related to CCA were reported in patients younger than 65 years of age ($10,481) compared with patients 65 years and older ($6,696)Citation4, representing higher costs in working-age patients. This group of patients had a higher mean age (69.1 years)Citation4, compared with the present CCA population in this analysis (52.4–52.6 years across cohorts), a shorter mean length of follow-up (229 daysCitation4 vs. a range of 614–725 days across cohorts in this analysis), and had failed at least one line of chemotherapy. Whereas reported costs from the previous analysis were higher than the mean all-cause healthcare costs (range: $10,321–$11,175) and inpatient costs (range: $3,798–$4,883) PPPM across CCA cohorts in our analysis, these disparities may be owing to differences in the patient inclusion criteria of each analysis; selecting for patients with previously treated CCA may have resulted in an older patient population with more advanced disease.

Productivity loss and burden of illness studies published in patients with HCC can provide useful comparisons with our data; although such comparisons should be interpreted with caution due to the divergent trajectories of care for HCC vs. CCA. In a study assessing the financial burden associated with HCC in the United States, the indirect cost (value of lost productivity) was $3,553 (10.8% of the total healthcare and productivity costs) and direct healthcare costs were $29,354 per patient (adjusted to 2006 US dollars)Citation13. The overall per-patient cost of HCC was $32,907, representing $7,845 PPPM after adjusting for average follow-upCitation13. Adjusting to 2019 US dollars, the overall PPPM cost of HCC was $9,949Citation14, which is lower than the sum of the mean indirect costs associated with productivity loss (range: $802–$966) and mean all-cause healthcare costs (range: $10,321–$11,175) PPPM in patients with CCA across cohorts in our analysis. In our study, mean indirect costs of CCA associated with productivity loss contributed to ∼6.7–8.6% of the total costs across cohorts, which is slightly lower than the contribution of indirect costs to the total per-patient costs reported in patients with HCCCitation13. Considering the scarcity of economic evaluations published in CCA, these comparisons provide valuable insights into the productivity loss, associated indirect costs, and direct healthcare costs in patients with CCA vs. patients with HCC, and highlight the high economic burden associated with CCA comparable to that of HCC.

The results of our analysis suggest that, in the United States, employed patients with CCA experience a substantial economic burden associated not only with direct healthcare utilization costs but also with indirect costs, such as time away from work. Thus, the productivity losses and indirect costs to patients owing to workplace absenteeism and short-term and long-term disability leave may result in an additional financial and emotional burden on patients with CCA who are already facing substantial hardship and decreased quality of life owing to their symptoms, emotional and cognitive effects, and treatment-related adverse eventsCitation15,Citation16.

All patients in this analysis had employer-sponsored private health insurance and many had access to paid healthcare leaves of absence, which is not available to all workers in the United States. For example, a survey in March 2021 showed that 79% of all US civilian workers had access to paid sick leave, but this decreased dramatically by wage, with only 35% of the lowest 10% of earners having access to paid sick leaveCitation17. In 2019, 56.4% of people in the United States had employer-sponsored private health insuranceCitation18. This suggests that patients in our analysis are more economically advantaged than the overall population of the United States, many of whom do not have access to paid sick leave or are not provided with insurance by their employers. Thus, our analysis may underestimate the productivity losses within the overall population of the United States.

The limitations of this study include those inherent in the analysis of administrative claims data. The Health and Productivity Management Database is limited to individuals with commercial health coverage; therefore, these findings may not be generalizable to patients with other insurance or without health insurance coverage. Absenteeism claims reflect any absence that a patient takes from work, and although some employers do provide some classification for absences (e.g. illness), no information is available on whether illness-related work absenteeism is specifically owing to CCA. Claims databases only include information on patients collected during their coverage by the health plan. In the MarketScan databases, patient information is only included in the database while they are covered by a health plan during continuous employment by an employer; if they end or switch their employment, any further claims would not be included in the database. As a result, all of a patient’s clinical claims may not be captured consistently. Formal statistical comparisons were not prespecified and not included in this study. Multiple comparisons reduce the statistical power of the analyses and the sample size was as available in the database, and as such no a priori hypothesis was being tested. Because new treatments for CCA could improve the well-being and quality of life of patients with CCA while reducing the financial burden of illness and absences from work on patients and the healthcare system, it is of interest to assess inpatient/outpatient utilization and costs for specific procedures and treatments for CCA. However, these data were not analyzed in this study. In the analysis of comorbidities (Supplementary Figure S1), it is possible that CCA was misdiagnosed as another type of gastrointestinal cancer in some patients during the diagnosis period, which may have contributed to the high rate of any malignancy as a comorbidity. Finally, data on the cancer stage were not collected; therefore, we cannot assess the effect that the cancer stage may have on productivity loss and costs. However, patients with CCA in this analysis had a mean length of follow-up of 614–725 days across eligibility cohorts, which may imply a population with a high proportion of early disease.

The strengths of this study are that it contributes valuable information on not only all-cause healthcare utilization costs in working patients with CCA in the United States, but also productivity losses and associated indirect costs owing to time away from work, which to our knowledge have not yet been studied in patients with CCA. In particular, the results demonstrate differences in workplace absenteeism, short-term disability, and long-term disability claims between patients with iCCA and eCCA, whereas to our knowledge other economic evaluations have not differentiated between these outcomes based on classification of CCA (iCCA vs. eCCA).

Conclusions

In summary, CCA is associated with substantial healthcare-related costs, including productivity losses, indirect costs owing to days missed from work, and direct medical costs in working-age patients. Overall, patients with iCCA incurred substantially more illness-related absence days, had a shorter time to long-term disability, and had greater median indirect costs related to productivity loss, mean days PPPM on short-term disability for CCA-related reasons, and mean all-cause total healthcare costs than patients with eCCA.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by Incyte Corporation (Wilmington, DE, USA). AT and SP are current or former employees of Incyte Corporation. Other employees of Incyte Corporation reviewed the manuscript and provided comments. All decisions regarding the manuscript were made and approved by the authors.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

SP is an employee of and receives stock options from Incyte Corporation. ET and JP are former employees of Merative (IBM Watson Health at the time of the analysis). AT was an employee of Incyte Corporation at the time this study was conducted and is currently an employee of and receives stock options from AstraZeneca.

Author contributions

All authors collaborated in the conception and design of the study, critically revised the content of the manuscript, read and approved the final manuscript for publication, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Reviewer disclosures

A reviewer on this manuscript has disclosed that they have been involved with research for Arcus, AstraZeneca, BioNtech, BMS, Celgene, Genentech/Roche, Helsinn, Puma, QED, Servier, Silenseed, Yiviva, and Consulting Alnylam, AstraZeneca, Autem, Beigene, Berry Genomics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Cend, CytomX, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Exelixis, Flatiron, Genentech/Roche, Helio, Helsinn, Incyte, Ipsen, Merck, Newbridge, Novartis, QED, Rafael, Servier, Silenseed, Sobi, Vector, Yiviva. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no other relevant financial relationships or otherwise to disclose.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (360.9 KB)Acknowledgements

Medical writing assistance was provided by Ciara Duffy, Ph.D., CMPP (Evidence Scientific Solutions, Sydney, Australia), and funded by Incyte Corporation. Part of this work was presented as a poster at the ASCO GI Cancers Symposium 2022 and AMCP Nexus 2022.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Merative. However, restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study and are not publicly available.

References

- Banales JM, Marin JJG, Lamarca A, et al. Cholangiocarcinoma 2020: the next horizon in mechanisms and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;17(9):557–588.

- Javle M, Lee S, Azad NS, et al. Temporal changes in cholangiocarcinoma incidence and mortality in the United States from 2001 to 2017. Oncologist. 2022;27(10):874–883.

- Wadhwa V, Jobanputra Y, Thota PN, et al. Healthcare utilization and costs associated with cholangiocarcinoma. Gastroenterol Rep. 2017;5(3):213–218.

- Chamberlain CX, Faust E, Goldschmidt D, et al. Burden of illness for patients with cholangiocarcinoma in the United States: a retrospective claims analysis. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2021;12(2):658–668.

- IBM Corporation. IBM MarketScan research databases [Internet]. Armonk (NY): IBM Corporation; 2021 [cited 2022 Mar 31]. Available from: https://www.ibm.com/products/marketscan-research-databases/databases

- IBM Corporation. IBM MarketScan research databases for life sciences researchers [Internet]. Somers (NY): IBM Corporation; 2021 [cited 2022 Mar 31]. Available from: https://www.ibm.com/downloads/cas/OWZWJ0QO

- United States Census Bureau. Annual social and economic supplements; current population survey, 2019 annual social and economic (ASEC) supplement conducted by the Bureau of the Census for the Bureau of Labor Statistics [Internet]. Washington (SC): U.S. Census Bureau; 2019 [cited 2022 Mar 30]. Available from: https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/cps/techdocs/cpsmar19.pdf

- Hill DB. Employer-sponsored long-term disability insurance. Monthly Lab Rev. 1987;110:16–22.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer price index [Internet]. Washington (DC): U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics; 2020 [cited 2022 Mar 30]. Available from: https://www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/cpi_01142020.htm

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology (NCCN guidelines): hepatobiliary cancers. NCCN; 2022 [cited 2022 Jun 24]. Available from: https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/guidelines-detail?category=1&id=1438

- Sarcognato S, Sacchi D, Fassan M, et al. Cholangiocarcinoma. Pathologica. 2021;113(3):158–169.

- Blechacz B, Komuta M, Roskams T, et al. Clinical diagnosis and staging of cholangiocarcinoma. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;8(9):512–522.

- Lang K, Danchenko N, Gondek K, et al. The burden of illness associated with hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. J Hepatol. 2009;50(1):89–99.

- U.S. Official Inflation Data Alioth Finance. $7,845 in 2006 is worth $9,948.58 in 2019 [Internet]. San Mateo (CA): Official Data Foundation; 2022 [cited 2022 May 10]. Available from: https://www.officialdata.org/us/inflation/2006?endYear=2019&amount=7845

- Patel N, Lie X, Gwaltney C, et al. Understanding patient experience in biliary tract cancer: a qualitative patient interview study. Oncol Ther. 2021;9(2):557–573.

- Hunter LA, Soares HP. Quality of life and symptom management in advanced biliary tract cancers. Cancers. 2021;13(20):5074.

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Paid sick leave was available to 79 percent of civilian workers in March 2021 [Internet]. Washington (DC): U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics; 2021 [cited 2022 May 10]. Available from: https://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2021/paid-sick-leave-was-available-to-79-percent-of-civilian-workers-in-march-2021.htm

- US Census Bureau. Current population survey, 2020 annual social and economic supplement (CPS ASEC): percentage of people by type of health insurance coverage: 2019 [Internet]. Washington (DC): US Census Bureau; 2020 [cited 2022 May 11]. Available from: https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/visualizations/2020/demo/p60-271/figure1.pdf