Abstract

Aims

To describe real-world use of esketamine (ESK) intranasal spray and healthcare outcomes among patients with treatment-resistant depression (TRD) in the United States (US).

Methods

Adults with TRD initiated on ESK (index date) between 5 March 2019 (US approval date for TRD) and 31 October 2020 were sampled from IBM MarketScan Research Databases. TRD was defined as claims for ≥2 unique antidepressants during the same major depressive episode. Subgroups of the TRD cohort with comorbid cardiometabolic conditions, pain, anxiety disorder, and substance use disorder (SUD) were identified. Patients had ≥6 months of continuous health plan eligibility pre- and post-index.

Results

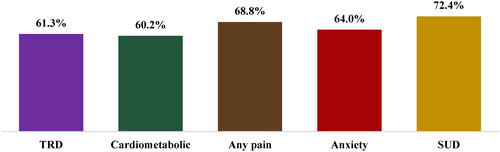

The TRD cohort comprised 269 patients; comorbidity subgroups included 123 (cardiometabolic), 144 (pain), 189 (anxiety disorder), and 58 (SUD) patients. Proportion of patients completing ≥8 ESK sessions (number of sessions in induction phase) was 61.3% in the TRD cohort and ranged from 60.2% (cardiometabolic subgroup) to 72.4% (SUD subgroup) in subgroups. Median frequency of induction sessions was every 5–8 days among the TRD cohort and subgroups. Mean mental health–related inpatient costs reduced from pre- to post-index periods in the TRD cohort (mean ± standard deviation [median] costs per-patient-per-6-months: $3,480 ± $13,328 [$0] pre-ESK initiation; $3,262 ± $16,666 [$0] post-ESK initiation; mean difference: –$218) and subgroups (largest decrease in cardiometabolic subgroup: $4,864 ± $14,271 [$0]; $2,792 ± $15,757 [$0]; –$2,072). Mean mental health–related emergency department (ED) costs decreased in the TRD cohort ($608 ± $2,525 [$0]; $269 ± $1,143 [$0]; –$339) and subgroups (largest decrease in the SUD subgroup: $1,403 ± $3,752 [$0]; $351 ± $868 [$0]; –$1,052).

Limitations

This is a descriptive analysis; sample size for some comorbidity subgroups is small.

Conclusions

The majority of patients completed ESK induction phase, and most dosing intervals were longer than the label recommendation. In this descriptive analysis, mental health–related inpatient and ED costs trended lower post-ESK initiation.

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a debilitating and often recurrent psychiatric condition affecting 8.4% of adults in the United States (US).Citation1 Approximately 30% of patients with MDD who receive pharmacological therapy, corresponding to 1.1% of the US adult population, experience treatment-resistant depression (TRD), a condition most commonly defined as inadequate response to two or more antidepressant treatment courses of adequate dose and duration.Citation2–4 It has been previously demonstrated that remission and response rates drop substantially after two antidepressant trials, complicating management of patients with TRD.Citation2

TRD, representing $43.8 billion in healthcare, unemployment, and productivity costs annually, is responsible for nearly half of the total annual burden of medication-treated MDD in the US.Citation4 With respect to productivity loss specifically, patients with TRD have an average of 35.8 work loss days each year, translating to a work loss rate of 1.7 times higher than employees without TRD and 6.2 times higher than employees without MDD. Patients with TRD also exhibit higher rates of comorbid physical and mental conditions, such as cardiometabolic disease or anxiety disorder, relative to the general population.Citation5 Additionally, among patients with comorbid conditions, those with TRD have been shown to have higher physical/mental condition–related healthcare resource use and medical costs relative to non-TRD MDD controls.Citation6,Citation7 Together, existing evidence suggests that TRD constitutes a considerable burden to the patients and the society at large.

Esketamine (ESK) is an intranasal spray approved for the treatment of TRD. In combination with an oral antidepressant, ESK has demonstrated efficacy in reducing depressive symptoms in as early as 24 h,Citation8 while oral antidepressants alone typically require 4–8 weeks to reach full effectiveness.Citation9 In phase 3 clinical trials of ESK among patients with TRD, most adverse events were mild to moderate and were transient.Citation8,Citation10 The safety profile of ESK includes the potential to increase blood pressure, and patients with cardiovascular and cerebrovascular conditions taking ESK may be at an increased risk of associated adverse events.Citation11 In the US, ESK is available only through the Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) distribution program and must be administered under direct supervision of a healthcare provider.Citation12

Given the approval of ESK for treating patients with TRD in the US since 2019,Citation13 it is essential to evaluate the use patterns of ESK in the real world. This study aimed to assess the real-world use of ESK and the association between ESK and healthcare resource use and costs among patients with TRD treated in US REMS-certified treatment centers, including those with a history of comorbid physical and mental conditions who may have elevated burden prior to treatment initiation.

Methods

Data source

Health insurance claims data from IBM MarketScan Commercial and Medicare Supplemental Databases (January 2015–October 2020) were used. Data were de-identified and included demographic and insurance eligibility information as well as medical and prescription drug claims of patients spanning all US census regions, with a concentration in the South and North Central regions. The data complied with the patient requirements of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996 as no individually identifiable information was collected; therefore, no review by an institutional review board was required per Title 45 of CFR, Part 46.101(b)(4).Citation14

Study design

This was a descriptive retrospective cohort study. The index window began on 5 March 2019 (ESK approval date for TRD); the index date was the date of the first ESK claim. The baseline period was the 6-month period preceding the index date, and the follow-up period was the 6-month period starting on the index date.

Study cohort and subgroups

The TRD cohort in this study included patients who met the definition for evidence of TRD (as defined below) prior to the initiation of ESK. Subgroups with a history of selected comorbid conditions commonly associated with depression were also identified to examine how the presence of these comorbidities may affect ESK treatment patterns and outcomes.Citation5,Citation15 The four non–mutually exclusive comorbidity subgroups included were the cardiometabolic subgroup, the pain subgroup, the anxiety disorder subgroup, and the substance use disorder (SUD) subgroup.

Sample selection

Patients were included in the TRD cohort if they met the following criteria: (1) had ≥1 pharmacy claim (National Drug Code [NDC]: 50458-0028-00, 50458-0028-02, 50458-0028-03) or medical claim (Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System [HCPCS] codes: G2082, G2083, S0013; International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Procedure Coding System [ICD-10- PCS]: XW097M5) for ESK with the first claim on or after 5 March 2019 (ESK approval date for TRD); (2) had evidence of TRD during the major depressive episode (MDE) in which ESK was initiated and before or on the index date; (3) had ≥1 claim with a diagnosis for MDD (International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-10-CM]: F32.X (excluding F32.8), F33.X [excluding F33.8]) during the MDE in which ESK was initiated; (4) had ≥6 months of continuous health plan eligibility before and after the index date; and (5) were ≥18 years old on the index date.

Patients in the comorbidity subgroups were additionally required to have ≥1 claim with a diagnosis or procedure for metabolic (diabetes, hypothyroidism, obesity) or cardiovascular (acute myocardial infarction, coronary artery disease, coronary artery bypass graft surgery, heart failure and cardiomyopathy, hypertension) conditions, pain, anxiety disorder, or SUD during the baseline period (Supplementary Table 1 for list of codes).

Patients were excluded from the study if they had ≥1 pharmacy or medical claim for ESK before 5 March 2019 or before evidence of TRD.

Definition of TRD

Evidence of TRD was defined as claims for ≥2 unique antidepressants during the MDE in which ESK was initiated. MDE was characterized by a period without gaps of ≥6 months without MDD diagnoses or antidepressants.

Outcome measures

ESK treatment sessions (number, frequency, and dose) were identified based on claims observed on distinct days. Per label, the induction phase of ESK comprises eight sessions, with ESK administered twice a week for 28 days; the first maintenance phase comprises four sessions (i.e. the 9th to 12th sessions), with ESK administered once weekly; and the second maintenance phase starts from the 13th session and should be individualized based on response.Citation12 The dose of an ESK treatment session was reported based on NDC and HCPCS codes for ESK pharmacy and medical claims. The recommended ESK dose is 56 mg on day 1 and 56 mg or 84 mg thereafter.Citation12

All-cause and mental health–related acute care medical costs (i.e. inpatient and emergency department [ED] costs), as well as outpatient medical costs, were assessed over the entire pre- and post-ESK periods and reported per-patient-per-6-months from a private payer’s perspective. Costs were adjusted for inflation using the medical care component of the US Consumer Price Index and reported in 2020 US dollars.

All-cause and mental health–related acute care healthcare resource utilization (i.e. inpatient visits and ED visits) reported per-100-patients-per-6-months, as well as outpatient visits reported per-patient-per-6-months, were also assessed over the entire pre- and post-ESK periods.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were descriptive using means, standard deviations (SDs), and medians to summarize continuous variables, and frequencies and proportions to summarize binary variables.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 269 patients were included in the TRD cohort, among which 123 were included in the cardiometabolic subgroup, 144 in the pain subgroup, 189 in the anxiety disorder subgroup, and 58 in the SUD subgroup (). The mean age of the TRD cohort was 44.6 years; across the comorbidity subgroups, the mean age ranged from 41.9 to 48.5 years. In the TRD cohort, 62.5% of patients were female; proportions of female were similar across comorbidity subgroups. Among patients in the cardiometabolic subgroup, 56.1% had a history of a comorbid cardiovascular condition during the baseline period; the most frequently observed cardiovascular condition in this subgroup was hypertension (53.7%), followed by coronary artery disease (7.3%), heart failure (1.6%), and coronary artery bypass graft (1.6%); none of the patients in the cardiometabolic subgroup had acute myocardial infarction.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics.

ESK treatment patterns

During the follow-up period, the mean [median] number of ESK treatment sessions was 11 [10] in the TRD cohort and ranged from 11 [9] (cardiometabolic subgroup) to 13 [11] (SUD subgroup) across the comorbidity subgroups.

In the TRD cohort, 61.3% completed at least the number of sessions in the induction phase of ESK (≥8 sessions)Citation12; this proportion ranged from 60.2% (cardiometabolic subgroup) to 72.4% (SUD subgroup) across the comorbidity subgroups (). The mean [median] time to completing 8 sessions was 56.9 [38.0] days in the TRD cohort and ranged from 54.8 [36.0] (anxiety disorder subgroup) to 63.6 [44.0] days (SUD subgroup) across the comorbidity subgroups. The median number of days between sessions during the induction phase ranged from 5 to 8 days among the TRD cohort and subgroups. Per label, time to complete ESK induction is 28 days with twice-a-week frequency of sessions.Citation12

Figure 1. Proportion of patients with ≥8 ESK treatment sessions. Abbreviations. Cardiometabolic: metabolic or cardiovascular condition; ESK: esketamine; SUD: substance use disorder; TRD: treatment resistant depression.

In the TRD cohort, 40.5% completed at least the number of sessions in the first maintenance phase of ESK (≥12 sessions)Citation12; this proportion was 36.6% in the cardiometabolic subgroup, 44.4% in the pain subgroup, 42.3% in the anxiety disorder subgroup, and 43.1% in the SUD subgroup. The mean [median] time from the 9th to the 12th session was 24.0 [21.0] days in the TRD cohort and ranged from 22.1 [21.0] (cardiometabolic subgroup) to 24.5 [21.0] days (pain subgroup) across the comorbidity subgroups. The median number of days between sessions during the first maintenance phase ranged from 6 to 8 days among the TRD cohort and subgroups. Per label, ESK is administered weekly during the first maintenance phase.Citation12

Most patients initiated ESK with the 56-mg dose, which is recommended per label,Citation12 including 78.1% in the TRD cohort, 78.0% in the cardiometabolic subgroup, 81.3% in the pain subgroup, 80.4% in the anxiety disorder subgroup, and 75.9% in the SUD subgroup. By the 12th session, most patients had titrated to the 84-mg dose, including 88.1% in the TRD cohort, 91.1% in the cardiometabolic subgroup, 87.5% in the pain subgroup, 83.8% in the anxiety disorder subgroup, and 96.0% in the SUD subgroup.

Medical costs during the 6-month post- versus pre-ESK period

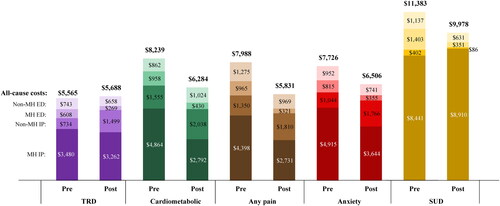

Overall, in the descriptive analysis conducted, the mean all-cause and mental health–related acute care medical costs generally trended lower in the 6-month period post- relative to pre- initiation of ESK (; Supplementary Table 2).

Figure 2. Mean acute care costs per-patient during the 6-month pre- and post-ESK periods. Abbreviations. Cardiometabolic: metabolic or cardiovascular condition; ED: emergency department; ESK: esketamine; IP: inpatient; MH: mental health; SUD: substance use disorder; TRD: treatment resistant depression.

While mean all-cause inpatient costs increased in the TRD cohort in the post-ESK period (mean ± SD [median] costs per-patient-per-6-months: $4,213 ± $16,576 [$0] pre-ESK initiation; $4,761 ± $20,147 [$0] post-ESK initiation; mean difference: +$547), mean mental health–related inpatient costs were lower ($3,480 ± $13,328 [$0]; $3,262 ± $16,666 [$0]; –$218). Thus, the increase was due to mean non-mental health-related inpatient costs (+$765), which were observed in only 8 patients in the cohort and were related to diseases of the circulatory and respiratory systems and general symptoms, signs and abnormal clinical and lab findings.

Further, mean all-cause inpatient costs decreased numerically in most comorbidity subgroups, including the cardiometabolic subgroup ($6,419 ± $20,190 [$0] pre-ESK initiation; $4,830 ± $20,250 [$0] post-ESK initiation; mean difference: –$1,589), the pain subgroup ($5,748 ± $20,145 [$0]; $4,541 ± $18,134 [$0]; –$1,207), and the anxiety disorder subgroup ($5,959 ± $19,522 [$0]; $5,410 ± $23,062 [$0]; –$549), except for the SUD subgroup ($8,843 ± $20,164 [$0]; $8,995 ± $32,141 [$0]; +$153). This was driven by numerical decreases in mean mental health–related inpatient costs in the comorbidity subgroups, with the largest decrease in the cardiometabolic subgroup ($4,864 ± $14,271 [$0]; $2,792 ± $15,757 [$0]; –$2,072); exception was the SUD subgroup in which an increase ($8,441 ± $19,256 [$0]; $8,910 ± $31,983 [$0]; +$469) was observed.

The mean all-cause ED costs decreased numerically in the TRD cohort ($1,351 ± $4,314 [$0] pre-ESK initiation; $927 ± $2,825 [$0] post-ESK initiation; mean difference: –$424) and comorbidity subgroups, with the largest decrease in the SUD subgroup ($2,541 ± $6,045 [$0]; $982 ± $2,671 [$0]; –$1,558). The mean mental health–related ED costs decreased numerically in the TRD cohort ($608 ± $2,525 [$0]; $269 ± $1,143 [$0]; –$339) and comorbidity subgroups, with the largest decrease in the SUD subgroup ($1,403 ± $3,752 [$0]; $351 ± $868 [$0]; –$1,052).

While mean costs of acute medical care generally trended lower in the 6-month period post- relative to pre-initiation of ESK, mean outpatient costs trended higher. The mean ± SD [median] all-cause outpatient costs increased from $7,340 ± $17,021 [$2,812] in the 6-month pre-ESK period to $10,183 ± $13,017 [$5,977] in the 6-month post-ESK period in the TRD cohort. Similarly, the costs were observed to increase in the cardiometabolic ($10,180 ± $23,120 [$4,332] pre-ESK initiation; $12,266 ± $15,520 [$6,584] post-ESK initiation), pain ($9,401 ± $21,352 [$4,415]; $11,955 ± $14,261 [$7,909]), anxiety disorder ($7,519 ± $13,860 [$3,280]; $10,825 ± $12,345 [$6,556]) and SUD ($11,141 ± $13,591 [$4,689]; $13,218 ± $14,890 [$6,911]) subgroups. The mean mental health–related outpatient costs increased from $4,106 ± $11,197 [$1,150] in the 6-month pre-ESK period to $6,610 ± $8,302 [$4,166] in the 6-month post-ESK period in the TRD cohort. Similarly, the costs were observed to increase in the cardiometabolic ($5,036 ± $14,244 [$1,421] pre-ESK initiation; $6,620 ± $7,748 [$3,832] post-ESK initiation), pain ($4,163 ± $12,749 [$1,386]; $6,854 ± $7,297 [$4,262]), anxiety disorder ($4,805 ± $12,950 [$1,449]; $7,559 ± $9,322 [$4,757]) and SUD ($7,593 ± $11,831 [$2,302]; $8,323 ± $8,010 [$5,419]) subgroups.

Healthcare resource utilization during the 6-month post- versus pre-ESK period

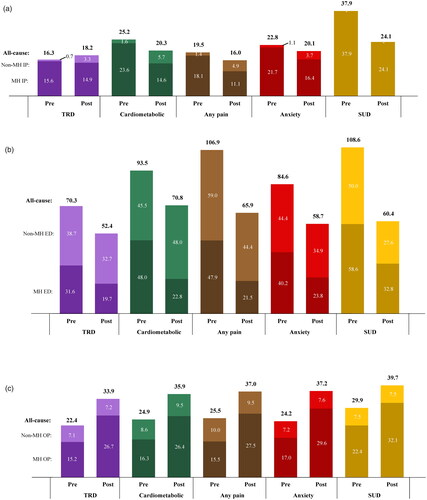

In the descriptive analysis conducted, the mean number of all-cause and mental health–related inpatient admissions in the cardiometabolic, pain, anxiety disorder, and SUD subgroups as well as ED visits in the TRD cohort and subgroups trended lower in the 6-month post relative to pre-ESK initiation period.

The mean number of all-cause inpatient admissions (reported per-100-patients-per-6-months) increased by 1.9 in the TRD cohort. This was driven by increase in the mean number of non-mental health-related inpatient admissions (+2.6 admissions), which were observed in 8 patients in the cohort. In the comorbidity subgroups, the decrease in all-cause inpatient admissions ranged from 2.7 (anxiety disorder subgroup) to 13.8 (SUD subgroup). The mean number of mental health–related inpatient admissions decreased in the TRD cohort (–0.7 admissions) and in the comorbidity subgroups, with the largest reduction in the SUD subgroup (–13.8 admissions) ().

Figure 3. (a) Mean number of inpatient admissions per 100 patients during the 6-month pre- and post-ESK periods. (b) Mean number of emergency department visits per 100 patients during the 6-month pre- and post-ESK periods. (c) Mean number of outpatient visits during the 6-month pre-and post-ESK periods. Abbreviations. Cardiometabolic: metabolic or cardiovascular condition; ED: emergency department; ESK: esketamine; IP: inpatient; OP: outpatient; MH: mental health; SUD: substance use disorder; TRD: treatment resistant depression.

The mean number of all-cause ED visits (reported per-100-patients-per-6-months) decreased in the TRD cohort (–17.9 visits) and comorbidity subgroups, with the largest reduction in the SUD subgroup (–48.2 visits). The mean number of mental health–related ED visits decreased across the TRD cohort and subgroups, with reductions ranging from 11.9 visits in the TRD cohort to 26.4 in the pain subgroup ().

Across the TRD cohort and subgroups, the mean number of all-cause and mental health–related outpatient visits per-patient-per-6-months increased in the post relative to the pre-ESK initiation period ().

Discussion

This descriptive study found that the majority of patients with TRD completed at least the number of sessions typically corresponding to the induction phase of ESK intranasal spray and had dosing intervals longer than the twice-a-week interval recommended per label. In the 6 months post- relative to pre-ESK initiation, reductions in mental health–related inpatient costs were observed in the TRD cohort and comorbidity subgroups (except the SUD subgroup), and reductions in all-cause and mental health–related ED costs were observed in the TRD cohort and all subgroups. The reductions in costs appeared to be driven by fewer mental health–related inpatient admissions, fewer all-cause ED visits, and fewer mental health–related ED visits in the TRD cohort and all subgroups.

Real-world ESK use patterns observed in the current study were not fully aligned with the recommendations in the ESK label for the TRD indication. The presence of comorbidities did not considerably affect how ESK was used. Factors that may explain longer intervals between ESK doses likely varied, and the reasons underlying the observed ESK treatment patterns were not captured in this study. Potential factors may include difficulties scheduling or re-scheduling an appointment for a treatment session, securing help to be driven to a treatment center, and coordinating time off-work. ESK therapy is offered only at REMS-certified treatment centers, typically on certain days of the week; thus, missing one treatment session can substantially prolong the dosing interval. Further, as entering the maintenance phase is a clinical decision based on assessment at the end of induction,Citation12 it is also expected that not all patients who complete induction phase may enter the maintenance phase. Finally, patient preference or clinician’s judgement on dosing schedule could have also impacted observed treatment patterns. Although the current study did not capture therapeutic benefits, it stands to reason that better compliance with the recommended frequency of ESK administration may translate to improved clinical outcomes for patients with depressive disorders.Citation9,Citation16 The impact of the real-world ESK dosing observed in this study should be further investigated, and strategies should be explored to improve ESK use patterns for patients with TRD.

Prior studies have shown that the presence of comorbidities is associated with the severity of depression.Citation17,Citation18 Additionally, among patients with mental and physical comorbidities, those with TRD have also been associated with higher healthcare resource utilization and costs compared with those with non-TRD MDD.Citation6,Citation7 These studies suggest that patients with TRD and comorbid conditions bear a considerable clinical and economic burden at baseline, which may explain the generally larger reductions in healthcare resource utilization and costs observed among patients with comorbidities in the current study. Specifically, apart from the inpatient costs in the SUD subgroup, reductions were observed in the mean mental health–related inpatient costs and admissions as well as the mean all-cause and mental health–related ED costs and visits across all comorbidity subgroups. The reduced need for acute care management among these patients following ESK initiation may be associated with the rapid improvement of depressive symptoms achieved by ESK, as shown in clinical trials.Citation12 The observed increases in outpatient medical costs and visits following ESK initiation are not surprising, as these likely captured administrations of ESK.

Limitations

Findings of this study should be considered in light of certain limitations. First, at the time this analysis was conducted, the data covered only 20 months of ESK use in the US clinical setting, and the sample size, particularly in some comorbidity subgroups, is low. While a 6-month time window was used in this study to preserve sample size, studies with more recent data and longer follow-ups are needed to confirm the trends in this descriptive analysis and test hypotheses related to outcomes of ESK use. Second, clinical information for identifying TRD was not available in claims data, and a definition of TRD based on pharmacy claims for antidepressants were used. Yet, because prior authorization is required for ESK to be covered by health insurance, it is unlikely that patients in this study received ESK without having TRD. Third, pharmacy claims do not guarantee that the medication dispensed was taken as prescribed and do not capture medications dispensed over the counter or as samples. Additionally, dates of ESK pharmacy claims may not correspond to the dates of ESK administration, and thus the time between ESK treatment sessions may be misestimated. Fourth, the results may not be generalizable to individuals without health insurance or those without commercial/Medicare supplemental insurance. Fifth, the required ≥6 months of follow-up may have led to immortal time bias. Lastly, in pre/post analyses, time-varying events may influence the association of treatment initiation with observed outcomes.

Conclusions

The majority of patients with TRD initiated on ESK intranasal spray in a real-world setting, including those with a history of comorbid conditions, completed induction treatment at dosing intervals longer than the label recommendation suggesting that it might be challenging for patients to routinely maintain appointments. Mental health–related inpatient admissions and costs post ESK initiation trended lower among patients with TRD and those with a history of comorbid cardiometabolic disease, pain, and anxiety disorder. Notable reductions were observed in all-cause and mental health–related ED costs post ESK initiation among patients with TRD, including those with comorbid cardiometabolic disease, pain, anxiety disorder, and SUD. Future studies should investigate the impact of the observed ESK dosing on real-world clinical outcomes of patients with TRD.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was supported by Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC. The sponsor commissioned the study but had no role in the decision to publish the final paper.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

KJ and SK are employees of Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, and are stockholders of Johnson & Johnson. DP, AS, and MZ are employees of Analysis Group, Inc., and CH is a former employee of Analysis Group, Inc., a consulting company that has provided paid consulting services to Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, which funded the development and conduct of this study and manuscript.

Author contributions

DP, AS, CH, and MZ contributed to study conception and design, collection and assembly of data, and data analysis and interpretation. KJ and SK contributed to study conception and design, data analysis and interpretation. All authors reviewed and approved the final content of this manuscript.

Reviewer disclosures

A reviewer on this manuscript has disclosed that they have received manuscript or speaker’s fees from Astellas, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Elsevier Japan, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Kyowa Yakuhin, Lundbeck Japan, Meiji Seika Pharma, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, MSD, Nihon Medi-Physics, Novartis, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Shionogi, Shire, Sumitomo Pharma, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Tsumura, Viatris, Wiley Japan, and Yoshitomi Yakuhin, and research grants from Eisai, Mochida Pharmaceutical, Meiji Seika Pharma, Shionogi and Sumitomo Pharma. The peer reviewers on this manuscript have no other relevant financial relationships or otherwise to disclose.

Previous presentations

Part of the material in this manuscript has been presented at the Psych Congress in San Antonio, TX, and Virtual, 29 October–1 November 2021, at the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology (ASCP) Annual Meeting in Scottsdale, AZ, 31 May–3 June 2022, and at the Neuroscience Education Institute (NEI) 2022 Congress in Colorado Springs, CO, 3–6 November 2022.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (31.9 KB)Acknowledgements

Medical writing support was provided by Flora Chik, an employee of Analysis Group, Inc.

References

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: results from the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP21-07-01-003, NSDUH Series H-56). Rockville (MD): Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2021.

- Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, et al. Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: a STAR* D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(11):1905–1917.

- Gaynes BN, Asher G, Gartlehner G, et al. Definition of treatment-resistant depression in the Medicare population. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2018.

- Zhdanava M, Pilon D, Ghelerter I, et al. The prevalence and national burden of treatment-resistant depression and major depressive disorder in the United States. J Clin Psychiatry. 2021;82(2):20m13699.

- Jaffe DH, Rive B, Denee TR. The humanistic and economic burden of treatment-resistant depression in Europe: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19(1):247.

- Zhdanava M, Kuvadia H, Joshi K, et al. Economic burden of treatment-resistant depression in privately insured U.S. patients with physical conditions. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2020;26(8):996–1007.

- Zhdanava M, Kuvadia H, Joshi K, et al. Economic burden of treatment-resistant depression in privately insured US patients with co-occurring anxiety disorder and/or substance use disorder. Curr Med Res Opin. 2021;37(1):123–133.

- Popova V, Daly EJ, Trivedi M, et al. Efficacy and safety of flexibly dosed esketamine nasal spray combined with a newly initiated oral antidepressant in treatment-resistant depression: a randomized double-blind active-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176(6):428–438.

- Gelenberg AJ, Freeman MP, Markowitz JC, et al. The American Psychiatric Association practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2010. p. 1–152.

- Daly EJ, Trivedi MH, Janik A, et al. Efficacy of esketamine nasal spray plus oral antidepressant treatment for relapse prevention in patients with treatment-resistant depression: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(9):893–903.

- Doherty T, Wajs E, Melkote R, et al. Cardiac safety of esketamine nasal spray in treatment-resistant depression: results from the clinical development program. CNS Drugs. 2020;34(3):299–310.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. SPRAVATO® (esketamine) prescribing information. Titusville (NJ): Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2020.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves new nasal spray medication for treatment-resistant depression; available only at a certified doctor’s office or clinic. 2019. [cited 2021 June 7]. Available from https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-new-nasal-spray-medication-treatment-resistant-depression-available-only-certified.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 45 CFR 46: pre-2018 requirements [cited 2020 Oct 16]. Available from: https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/regulations/45-cfr-46/index.html#46.101.

- Davis L, Uezato A, Newell JM, et al. Major depression and comorbid substance use disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2008;21(1):14–18.

- Geddes JR, Carney SM, Davies C, et al. Relapse prevention with antidepressant drug treatment in depressive disorders: a systematic review. York (UK): Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (UK); 2003. [cited 2022 June 6]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK70041/

- Cancino A, Leiva-Bianchi M, Serrano C, et al. Factors associated with psychiatric comorbidity in depression patients in primary health care in Chile. Depress Res Treat. 2018;2018:1–9.

- Ziobrowski HN, Leung LB, Bossarte RM, et al. Comorbid mental disorders, depression symptom severity, and role impairment among veterans initiating depression treatment through the Veterans Health Administration. J Affect Disord. 2021;290:227–236.