Abstract

Background

No research to date has examined antipsychotic (AP) use, healthcare resource use (HRU), costs, and quality of care among those with schizophrenia in the Medicare program despite it serving as the primary payer for half of individuals with schizophrenia in the US.

Objectives

To provide national estimates and assess regional variation in AP treatment utilization, HRU, costs, and quality measures among Medicare beneficiaries with schizophrenia.

Methods

Cross-sectional descriptive analysis of 100% Medicare claims data from 2019. The sample included all adult Medicare beneficiaries with continuous fee-for-service coverage and ≥1 inpatient and/or ≥2 outpatient claims with a diagnosis for schizophrenia in 2019. Summary statistics on AP use; HRU and cost; and quality measures were reported at the national, state, and county levels. Regional variation was measured using the coefficient of variation (CoV).

Results

We identified 314,888 beneficiaries with schizophrenia. About 91% used any AP; 20% used any long-acting injectable antipsychotic (LAI); and 14% used atypical LAIs. About 28% of beneficiaries had ≥1 hospitalization and 47% had ≥1 emergency room (ER) visits, the vast majority of which were related to mental health (MH). Total annual all-cause, MH, and schizophrenia-related costs were $23,662, $15,000 and $12,109, respectively. Among those with hospitalizations, 18.4% and 27.3% had readmission within 7 and 30 days and 56% and 67% had a physician visit and AP fill within 30 days post-discharge, respectively. Overall, 81% of beneficiaries were deemed adherent to their AP medications. Larger interstate variations were observed in LAI use than AP use (CoV: 0.21 vs 0.02). County-level variations were larger than state-level variations for all measures.

Conclusions

In this first study examining a national sample of Medicare beneficiaries with schizophrenia, we found low utilization rates of LAIs and high levels of hospital admissions/readmissions and ER visits. State and county-level variations were also found in these measures.

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a severe, chronic, and disabling mental illness characterized by multidimensional symptoms such as psychosis, reduced emotional responsiveness, and cognitive impairmentCitation1. There are many different subtypes of schizophrenia given the condition can be due to one or more neurobiological processesCitation2. While the estimated prevalence of schizophrenia ranges from 0.25% to 1.1% in the United StatesCitation3–6, it is associated with significant health, social, and economic burdensCitation1. For instance, individuals with schizophrenia have a higher risk of premature deathCitation7–9 and the excess economic burden of schizophrenia was an estimated $62 billion in direct healthcare costs alone in 2019Citation10.

Antipsychotic (AP) medications are the mainstay therapy for the management of this serious mental illness. Adherence to these medications is critical to improve disease symptoms, reduce the risk of acute psychotic episodes, and decrease the frequency of relapses and psychiatric hospitalizations. Yet many individuals with schizophrenia on oral antipsychotics find it challenging to maintain adherence to their daily regimen in the real-world settingCitation11–13. Nonadherence to AP medications is associated with higher likelihood of relapseCitation14, more medical hospitalizationsCitation15, substance abuse, and arrestsCitation16. The introduction of long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAIs) provided an important treatment option for patients since these agents need to be administered less frequently than the daily use of oral antipsychotic medications. While first-generation antipsychotic (FGA) LAIs have typically been monthly injections, some second-generation antipsychotic (SGA) LAIs have offered the benefit of even less frequent administration (e.g. injections to be taken once every 2 months, 3 months, or 6 months). In addition to being more convenient for patients and improving a subjective sense of symptom control, LAI treatment affords fewer opportunities to miss doses and facilitates more engaged clinical management given physicians can be immediately made aware of missed visits or injections before the recurrence of symptomsCitation17–20. Previous observational research has shown LAI use—particularly SGA LAI useCitation21–23—to be associated with lower rates of non-adherence and/or discontinuation, decreased risk of schizophrenia-related hospitalizations, and reduced risk of mortality relative to OAPs in the real-world settingCitation24–29.

Despite their benefits, numerous studies have shown that LAIs are underutilized across various settings in the U.S.Citation17,Citation30–32. At the same time, studies show high rates of health care resource use, particularly emergency room visits and hospital admissions, and associated costs suggestive of poor management of schizophreniaCitation33–35. Research also suggests suboptimal quality of care with respect to key quality indicators such as rates of hospital readmissions, continuity of care after hospital discharge, and AP medication adherence among individuals with this serious mental illnessCitation36–38.

Surprisingly, all the U.S. studies to date on antipsychotic utilization, health care resource use, costs, and quality of care have focused on individuals with schizophrenia covered by either private insurance, Veterans Affairs, or Medicaid. None have examined elderly and/or disabled individuals with schizophrenia receiving coverage from Medicare, a federally funded health insurance program in the U.S.Citation39. This is a critical gap in the literature for several reasons. First, Medicare is the primary payer for half of all individuals with schizophrenia in the U.S. Second, the vast majority of these patients are severely disabled and low-income with >90% eligible for the Medicare Part D low-income subsidy (LIS), indicating an income below 135% of the federal poverty level, which makes them a particularly vulnerable populationCitation40. Third, access to national data on medical and prescription claims linked with eligibility data are available for all Medicare beneficiaries from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) for research purposes. The availability of national data permits a baseline population-level assessment of the schizophrenia treatment management, health care resource and cost burden, and quality of care in one of the largest, albeit under-studied group of individuals with schizophrenia and informs federal officials of areas for further investigation and potential quality improvement initiatives and policy interventions. Furthermore, the availability of national data also permits assessment of these measures by state and county of residence. These findings could then inform policies and decisions related to health care resource availability and clinical care for serious mental illnesses that typically occurs at the local level.

The objectives of this study were (1) to provide national-level, state-level, and county-level estimates of antipsychotic treatment utilization, HRU, healthcare costs, and quality measures among all fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries with schizophrenia in the U.S.; and (2) to examine geographic variation by state and county of residence in these measures.

Methods

Data source

This study used the Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse (CCW) 100% Medicare files for 2019 available from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). The CCW 100% Medicare files contain data on all fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries in the United States. The CCW database includes Medicare Part A and Part B medical claims as well as Part D prescription drug event (PDE) files, which are linked to Medicare personal summary files that contain patient demographics and eligibility information.

The University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board deemed this study to be exempt from institutional review per Title 45 of Code of Federal Regulations, Part 46.101(b)(4)Citation41.

Study design and sample selection

This study was a cross-sectional descriptive study. Beneficiaries were included in the sample if they met the following criteria in the year 2019: (1) ≥1 inpatient claim and/or ≥2 outpatient claims on different days with a diagnosis of schizophrenia (ICD-10-CM: F20.XX, F21, and F25.X) in any position, (2) continuous Medicare fee-for-service and stand-alone Part D prescription plan coverage, (3) absence of ≥1 inpatient claim and/or ≥2 outpatient claims on different days with a diagnosis (ICD-10-CM: F31.xx) for bipolar disorder in any position, (4) age ≥18 years, (5) non-missing state code (i.e. FIPS code), and (6) residence in one of the 50 states plus D.C. (i.e. excluded beneficiaries from Puerto Rico, U.S. Virgin Islands, and Guam). All patients in the Medicare population meeting the above inclusion criteria were included in our study sample. No sampling (e.g. consecutive or random sampling) was conducted.

Outcome measures

Outcome measures included antipsychotic treatment utilization rates, HRU, and healthcare costs and quality metrics during 2019. The measures were described at the national level as well as at the state and county level. antipsychotic utilization rates were defined as the proportion of all beneficiaries with schizophrenia in 2019 with ≥1 claim for the specific antipsychotic. We report the utilization rates for any antipsychotic, any LAI, and any oral antipsychotics (OAP) only (i.e. only use of OAP without LAI use in 2019). We also report the utilization rates specifically for SGAs, namely any SGA, any SGA LAI, and any SGA OAP only (i.e. any SGA OAP use without LAI use in 2019).

HRU measures included the proportion of all beneficiaries with schizophrenia in 2019 with any inpatient admission, any emergency room (ER) visit, and any evaluation and management (E&M) physician visit. We also assessed the mean number of admissions/visits among those with evidence of at least one admission/visit in 2019. Similarly, the total length of stay among those with any inpatient admission in 2019 was also examined. Healthcare cost measures included total healthcare costs, medical costs and pharmacy costs. Medical costs were retrieved from the Medicare Part A and B medical claims including the inpatient, hospital outpatient, and carrier claims files in 2019. The HRU and cost measures were categorized as all-cause, mental health-related, and schizophrenia-related. Mental health-related HRU and medical cost measures were defined based on claims with an ICD-10 diagnosis code between F00 and F99 (inclusive) in any diagnosis position. Schizophrenia-related HRU and medical cost measures were defined based on claims with an ICD-10 diagnosis code of F20.XX, F21, and F25.X in any diagnosis position. Pharmacy costs were based on Medicare Part D prescription drug claims. All-cause pharmacy costs included costs for all prescription drug claims during 2019. Mental health-related pharmacy costs were defined as costs for claims with National Drug Codes (NDCs) for mood stabilizers, anxiolytics, antidepressants, and antipsychotics. Schizophrenia-related pharmacy costs were defined as costs for antipsychotics.

We assessed four quality measures informed by metrics used by CMSCitation42–44. We first examined antipsychotic medication adherence among beneficiaries using an antipsychotic prescription based on the proportion of days covered (PDC) methodCitation45. The rate of antipsychotic medication adherence was defined as the percentage of beneficiaries using AP medications in 2019 who had a PDC greater than or equal to 80%. The PDC was defined as the number of days in the observation period that are covered with a days’ supply from any antipsychotic medication (i.e. OAP or LAI) divided by the total number of days in the observation period (i.e. from the date of the earliest antipsychotic prescription received in 2019 until 31 December 2019Citation44) All OAPs and the vast majority of LAIs were billed under the Part D prescription claims, which have a days’ supply field available to allow counting of days covered. For the small number of LAI prescriptions found under Part B medical claims, which lack the days’ supply field present on pharmacy claims, the days’ supply was assigned based on the recommended dosage regimen in the prescribing information for that injection (e.g. 15 days for the every-2-weeks risperidone LAI)Citation46. In sensitivity analysis, we similarly assigned the days’ supply for LAI prescription claims billed under Part D, however, the PDC estimates remained very similar and hence are not reportedCitation46.

Besides antipsychotic medication adherence, 3 quality measures were reported among Medicare beneficiaries with ≥1 all-cause inpatient admission between 1 January 2019 and 1 December 2019, wherein we assessed the proportion of beneficiaries with: (1) any inpatient readmission within 7 days and 30 days post-discharge, (2) any physician visit for evaluation and management (E&M visit) within 30 days post-discharge, and (3) any antipsychotic medication dispensed within 30 days post-discharge.

Analysis

Patient characteristics were described for the overall national sample and the Part D LIS subgroups. Sociodemographic characteristics such as age, sex, race/ethnicity, Part D low-income subsidy (LIS) status, original reason for Medicare eligibility, census region, and metropolitan status of residence were examined. Several clinical characteristics were also described. Since schizophrenia has several subtypes, we report the type of schizophrenia disorder identified via diagnosis codes in the medical claims. Comorbidity burden was measured via the Elixhauser comorbidity indexCitation47,Citation48 specified as the count of the number of comorbidities (<2, 3–4, 5+) as well as indicators for select physical comorbidities and mental comorbiditiesCitation3.

Summary statistics on antipsychotic medication use, HRU and cost, and quality measures were reported at the national, state, and county levels. Mean and standard deviation (SD) were reported for continuous variables; count and proportion were reported for categorical variables. It should be noted that we report arithmetic mean for the cost measures despite potential skewness since the arithmetic mean is the policy relevant parameter of interest for policymakers and other decision makersCitation49. This is because from the budgetary perspective it allows decision-makers to calculate the total costs incurred (i.e. arithmetic mean cost times the number of patients equals total cost).

Regional variation was reported at the state and county-levels. Regional variation across the 50 states plus D.C. was described using state-level mean, median, 25th percentile, 75th percentile, and the coefficient of variation ([CoV] i.e. SD divided by the mean) for each measure of interest. Regional variation at the county-level was measured similarly across all counties in the U.S. which had greater than 10 beneficiaries from our sample residing in that county. In addition to reporting the measures in the overall sample, we report results separately for subgroups defined by the Part D LIS status. LIS individuals have lower incomes and face significantly subsidized prescription cost sharing compared to non-LIS individuals, which can impact antipsychotic use, adherence, and other measures of interest. Following the CMS reporting criteria, estimates based on <11 beneficiaries were not reported.

All analyses were conducted using SAS Enterprise Guide 9.4 versionCitation50.

Results

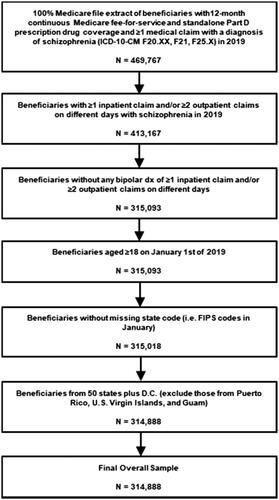

The final overall national sample included 314,888 fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries with schizophrenia in 2019 across the 50 states plus D.C. (). The mean age of the overall sample was 56.5 years (SD 15.0) and 68.5% of the beneficiaries were <65 years old (). Most of the sample was male (58.8%) and White (65.5%). About 91% of the sample received LIS under Medicare Part D; the vast majority (95.2%) of the LIS patients were dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid. The comorbidity burden was substantial, with 75.7% of beneficiaries having 5+ Elixhauser comorbidities. Common physical comorbidities included hypertension (58.9%), diabetes (with [22.6%] and without complications [33.0%]), and obesity (28.8%). Common mental comorbidities included depressive disorders (35.2%), anxiety disorders (34.9%) and substance-related and addictive disorders (29.2%) ().

Table 1. Characteristics of National Sample of Fee-for-Service Medicare Beneficiaries with Schizophrenia in 2019.

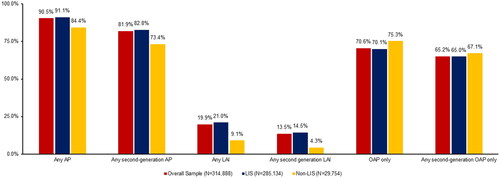

About 90% of the overall national sample had evidence of any antipsychotic use; 20% used any LAI and 14% used an SGA LAI in 2019 (). Given that vast majority of the sample was receiving LIS, results were similar for the LIS beneficiaries and the overall sample. Larger differences were observed in antipsychotic use between LIS and non-LIS beneficiaries. Rates of any LAI use were over double (21.0% vs. 9.1%) and rates of any SGA LAI use were more than triple (14.5% vs. 4.3%) among LIS beneficiaries compared to non-LIS beneficiaries ().

Figure 2. Antipsychotic utilization in the national sample of fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries with schizophrenia in 2019, overall and by Part D low income subsidy status. Abbreviations. LIS, Low-income subsidy; AP, antipsychotic medication; OAP, oral antipsychotic medication; LAI, long-acting injectable.

About 28% of the overall national sample had ≥1 all-cause inpatient admission with the mean number of hospitalizations of 2.0 (SD: 1.7) and total length of stay (LOS) of 27.4 days (SD: 76.4) in 2019 (). Approximately half of the sample (47%) had ≥1 all-cause emergency room (ER) visit with a mean number of visits of 4.3 (SD: 6.0) in 2019, of which the vast majority (94.7%) were mental health-related. Additionally, most mental health-related HRU was related to schizophrenia. No major differences in the HRU measures were observed between LIS and non-LIS beneficiaries ().

Table 2. Annual healthcare resource utilization in the national sample of fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries with schizophrenia in 2019, overall and by Part D low income subsidy status.

Total all-cause healthcare costs were $23,662 (SD: $31,923) per person per year in the overall national sample (). Approximately two-thirds of these costs were mental health-related ($15,000) and most mental health-related costs were attributable to schizophrenia ($12,109). LIS beneficiaries had higher total all-cause costs than non-LIS beneficiaries ($24,092 vs. $19,537), with the difference largely attributable to higher pharmacy costs ($10,892 vs. $4,909) among LIS compared to non-LIS beneficiaries. Similar patterns of differences between LIS and non-LIS beneficiaries were observed for mental health-related and schizophrenia-related costs.

Table 3. Annual healthcare costs in the national sample of fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries with schizophrenia in 2019, overall and by Part D low income subsidy status.

Over 80% of the antipsychotic users in our overall national sample were deemed adherent to antipsychotics based on PDC ≥ 0.80 (). Among beneficiaries with an inpatient admission, 18.4% had evidence of an inpatient readmission within 7 days of discharge and 27.3% had evidence of an inpatient readmission within 30 days of discharge. Only slightly over half of beneficiaries (55.6%) had E&M physician visits within 30 days of discharge. Over two-thirds of beneficiaries (67.1%) had evidence of an antipsychotic dispensed within 30 days of discharge. Major differences were mainly observed between the LIS and non-LIS beneficiaries in the antipsychotic medication related quality measures, namely LIS beneficiaries had a higher antipsychotic adherence rate (81.3% vs 76.5%) and a higher antipsychotic dispensed rate (68.3% vs 57.1%) compared to non-LIS beneficiaries ().

Table 4. Quality measures in the national sample of fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries with schizophrenia in 2019, overall and by Part D low income subsidy status.

presents measures of variation at the state-level and county-level in key metrics of antipsychotic utilization, HRU, costs, and quality of care in the overall national sample. Larger interstate variations were observed for any LAI use than any antipsychotic medication use (CoV: 0.21 vs 0.02; interquartile range [IQR]: 5.8% vs 2.0%). Similarly, large interstate variations were observed for inpatient admissions and inpatient total length of stay relative to other HRU measures. County-level variations were larger than state-level variations for all measures. For example, the CoV for the rate of all-cause hospital admissions was 0.34 vs 0.11. Similarly, the CoV was 0.24 vs 0.08 for all-cause costs ().

Table 5. State and county-level variations in selected measures of antipsychotic utilization, healthcare resource utilization, costs, and quality of care in a national sample of fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries with schizophrenia, 2019.

Supplementary Table 1a presents the key measures for each of the 50 states plus D.C. for the overall sample. LAI use among all Medicare beneficiaries with schizophrenia was the lowest in Massachusetts (14%) and the highest in Arizona (33%) (Supplementary Table 1a). Total all-cause healthcare costs ranged from as low as $17,216 (New Mexico) to as high as $27,647 (California) (Supplementary Table 1a). Rates of 30-day inpatient readmissions ranged from 19% (Hawaii) to 34% (Florida) (Supplementary Table 1a). The percentage of beneficiaries adherent to antipsychotic medications also ranged from as low as 71% in DC to as high as 88% in North Dakota. Large variations were also identified across the states for LIS beneficiaries (Supplementary Tables 1b and 3).

Supplementary Table 2a presents the key measures for each of the counties for the overall sample. Similar to the results in , the differences were even larger among the highest and lowest ranking region in the county-level results than the state-level results. For instance, LAI use among all Medicare beneficiaries with schizophrenia was lowest in Washington County, Vermont (8%) and highest in Hampton County, South Carolina (72%) (Supplementary Table 2a). Total all-cause healthcare costs ranged from as low as $7,492 (Shelby County, Texas) to as high as $54,870 (Decatur County, Illinois) (Supplementary Table 2a). Rates of 30-day inpatient readmissions ranged from 12% (Santa Cruz County, California) to 69% (Mohave County, Arizona) (Supplementary Table 2a). Even within the same state, large county-level variations were observed. For example, within North Carolina, large county-level variations were found in LAI use (14% [Stanly and Iredell] to 36% [Franklin]), all-cause hospitalizations (19% [Randolph and Rutherford] to 48% [Granville]), all-cause ER visits (32% [Watauga] to 69% [Pender]), all-cause total costs ($11,871 [Currituck] to $35,316 [Jones]), and 30-day hospital readmissions (17% [Gaston] to 38% [Cumberland]). Large variations were also identified across the counties for LIS beneficiaries (Supplementary Tables 2b and 4).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine a national sample of fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries with schizophrenia and produce a baseline understanding of their antipsychotic treatment utilization, healthcare resource use, costs, and quality of care at the national, state, and county level. As such, it offers several important insights into this under-studied population that have direct implications for policy, clinical practice, and potential directions for future research.

Over 90% of beneficiaries were receiving the low-income subsidy (LIS) benefits to cover their cost sharing for prescription drugs under Medicare Part D. Receipt of LIS likely serves as a proxy measure for low socioeconomic status. Additionally, over two-thirds of beneficiaries were less than 65 years old, meaning they qualified for Medicare due to disability and not age. Despite being younger, Medicare beneficiaries with schizophrenia had a high comorbidity burden with about three-quarters having 5 or more comorbidities, with particularly high rates of cardiometabolic comorbidities and co-occurring mental conditions. Our findings are consistent with previous literature which has linked schizophrenia with high rates of such comorbid illnessesCitation51. The combination of the above factors along with our other findings discussed below suggests that the fee-for-service Medicare population with schizophrenia represents a particularly vulnerable subgroup at risk of poor outcomes needing additional attention from researchers, mental health providers, and policymakers.

Most Medicare beneficiaries with schizophrenia had some evidence of AP treatment utilization, with 90% of beneficiaries having evidence of at least one AP medication fill. However, AP use was largely limited to oral AP medications, with slightly over 70% of beneficiaries receiving oral treatment only. LAIs were used by only 1 in 5 Medicare beneficiaries with schizophrenia in 2019 (two-thirds received an SGA LAI but one-third received an FGA LAI only). Over the same time frame, we also found that about a quarter of the beneficiaries had an inpatient admission and over half of beneficiaries had an ER visit, with the vast majority being mental health-related. Beneficiaries who were hospitalized had an average of two inpatient admissions and those with an ER visit had an average of 4 visits in the same year. The all-cause and mental-health related costs were also substantial in this population. One explanation for this finding may be sub-optimal management of high-risk beneficiaries with schizophrenia resulting in repeated hospitalizations and ER visits and associated clinical and economic burden. In fact, our study found that nearly half the beneficiaries did not have an outpatient physician visit for evaluation and management within 30 days of hospital discharge and more than 1 in 4 beneficiaries had an inpatient readmission within 30 days of discharge. However, the concurrently observed high rates of antipsychotic adherence (as measured based on prescription refills) in our study seem counterintuitive to the above findings and could suggest that patients are filling prescriptions but not consuming the pills.

When taken together, these descriptive findings suggest the need for better management of schizophrenia in this population. One of the key missed opportunities by mental health providers and health systems surrounds the prescribing and uptake of LAIs given the generous access to these agents under Medicare Part D. All antipsychotics (OAPs, FGA LAIs, and SGA LAIs) must be covered on plan formularies due to their status as a “protected” drug class under Medicare Part D. Further, the vast majority (over 90%) of beneficiaries with schizophrenia face nominal copayments for these agents due to their Part D LIS status, and thus out-of-pocket costs are unlikely to pose a burdenCitation52. In the absence of these traditional access barriers, additional research is needed to identify and address other patient, provider, and system-level barriers to wider LAI prescribing and uptake specifically in the Medicare population given the numerous advantages of these agents outlined in the recent American Psychiatric Association (APA)Citation53 and other clinical practice guidelinesCitation54–59. For instance, one common explanation for lower LAI uptake is patient anxiety around the potential discomfort of injectionsCitation17. To address this barrier, the APA guideline suggests that clinicians can minimize discomfort by administering SGA LAIs rather than FGA LAIs, which have sesame oil-based vehicles or using LAIs with longer dosing intervals and hence requiring less frequent administrationsCitation53. Evidence also suggests that clinicians fail to consider LAIs as a treatment option even when a patient would be an ideal candidateCitation60–62. Health systems and behavioral health centers could address this issue using computerized clinical decision support systems to alert physicians to consider an LAI for Medicare beneficiaries who are appropriate candidates (e.g. history of non-adherence, recent ER visit or inpatient discharge, co-occurring substance use disorder)Citation53.

Additional research is also needed to identify factors (in addition to non-adherence) that are associated with hospital readmissions and repeated ER visits specifically in the Medicare population so as to inform the characteristics of patient subgroups at greater risk and what modifiable factors can be targeted for interventions. For instance, lack of access to transportation may be a real issue in our study population which primarily consists of very low-income patients typically dually eligible for Medicaid. This may become a logistical barrier to travel to the clinic for outpatient follow-up after inpatient discharge or even for regular medical appointments. Another way this barrier can be addressed is with policies promoting access to transportation assistance. For instance, some states have revised Medicaid regulations to make it easier for ride-sharing companies such as Uber and Lyft to provide nonemergency transportation to medical appointmentsCitation63. If transportation access is a barrier for LAI use, which requires regular visits for the injection administrations, clinicians can also consider prescribing longer dosing interval LAIs requiring fewer visits to the clinic.

Another key finding of our study was significant state and county-level variations with respect to AP medication use, HRU, costs, and quality measures for Medicare beneficiaries with schizophrenia. It should also be noted that substantial variation existed even between states that are relatively close geographically and demographically. For instance, while the rate of LAI use was 33% in Arizona, it was only 17% in California. We also observed significant state-level differences in annual HRU and healthcare cost measures. There were also large differences in the rate of 30-day inpatient readmissions as well as post-discharge follow-up physician visits. Given that outpatient follow-up after discharge can improve medication adherence and reduce the risk of rehospitalization, our findings highlight a significant unmet need for beneficiaries with schizophrenia in certain regions of the countryCitation21. County-level variations were larger than state-level variations for all measures. Future research should evaluate reasons for these geographic variations (e.g. whether it is due to regional variations in access to healthcare resources) and specifically whether the absence or presence of modifiable factors such as availability of community-based mental health services (e.g. certified community behavioral health clinics) in the county and state policies (e.g. authorizing pharmacists to administer LAIs) contribute to the variationsCitation64,Citation65.

State and local policymakers and mental health providers undoubtedly have a role to play in developing targeted policies and quality improvement initiatives for beneficiaries with schizophrenia and address these geographic disparities, other approaches may involve policies and initiatives targeted for schizophrenia under the federal Medicare program. One possibility is through enhanced use of Medicare Part D medication therapy management (MTM) programs for Medicare beneficiaries with schizophrenia. Currently, all Medicare Part D plan sponsors are required to offer an MTM program as part of their services. However, recent work suggests that beneficiaries with mental health conditions such as schizophrenia, though more likely to be enrolled in an MTM than a beneficiary without such a condition, generally receive fewer comprehensive medication reviews as part of their MTMCitation66.

Finally, our study also found key differences between beneficiaries receiving the low-income subsidy (more than 90% of our sample) and beneficiaries who were not receiving the subsidy (non-LIS). Lower proportions of non-LIS beneficiaries were using LAIs relative to LIS beneficiaries (9% vs 21%). In general, non-LIS beneficiaries performed worse in quality measures compared to LIS beneficiaries: non-LIS beneficiaries had lower adherence rates for antipsychotics, higher readmission rates, and lower AP dispensed rate post discharge. Lower LAI use and lower adherence to antipsychotics may be due to the fact that non-LIS beneficiaries face higher cost-sharing for prescription drugs than LIS beneficiariesCitation52. The recently passed Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) includes provisions to cap annual out-of-pocket costs under Medicare Part D and gives non-LIS beneficiaries the option to smooth out these costs by paying them in monthly installmentsCitation67. Hopefully, these reforms will alleviate the financial burden placed on non-LIS beneficiaries with schizophrenia. It will be important to assess how the Medicare Part D benefit design changes implemented by the IRA impact access and adherence to LAIs and long-term outcomes among these Medicare beneficiaries with schizophrenia.

Our study had several limitations. First, our sample included Medicare beneficiaries with fee-for-service coverage and hence our findings may not be generalizable to those with Medicare Advantage (i.e. Medicare beneficiaries covered by managed care plans). Future research should be conducted in this population. Second, there were limitations commonly associated with claims databases which depend on correct diagnosis, procedure, drug and billing codes. The coding inaccuracies may lead to case misidentification. Third, this was a cross-sectional study using 2019 data. We could not determine causality between our observed measures (for example, between AP utilization and HRU measures). Furthermore, our sample selection requirement that beneficiaries have ≥1 inpatient claim and/or ≥2 outpatient claims on different days with a diagnosis for schizophrenia during the calendar year of 2019 may underestimate the number of beneficiaries with schizophrenia (i.e. beneficiaries with a single outpatient diagnosis in the study year but another one in the previous or next year will be excluded). Fourth, our proportion of days covered measure (based on prescription fill data) may not accurately reflect the true antipsychotic adherence. As with all claims database studies, prescription fills do not account for whether the medication dispensed was taken as prescribed, potentially overestimating adherence. Further, we followed the HEDIS approachCitation44 in assessing adherence from the date of the earliest antipsychotic prescription received by each patient in 2019 until the end of the year rather than over the entire year (i.e. fixed 365-day period). This method avoids underestimating adherence for patients who may have filled a 90-day antipsychotic fill in December 2018 (i.e. outside our study data period). However, this approach overestimates adherence for patients who did not have any antipsychotic days supply at hand before their first antipsychotic fill date in 2019. If we had used a fixed 365-day period instead of the period between first fill date and end of 2019, our adherence estimates would have been much lower (i.e. 72% vs. 81%, respectively, in the overall sample). Also, LAIs received in an inpatient setting may not have been recorded as a prescription, and as such will not be captured in our analysis. Finally, due to CMS reporting requirements, measures for some counties were not reported due to small sample sizes.

In conclusion, this first national study of all fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries with schizophrenia found low utilization rates of LAIs, high hospital admission and ER visit rates and costs, and poor performance on quality measures of readmissions and continuity of care after hospital discharge. State and county-level variations were found in these measures, with larger variations reported for LAI use, hospital admissions, readmissions, and costs. Our findings identify opportunities to improve schizophrenia management and quality of care and highlight significant unmet need in this vulnerable population, overall and particularly among those residing in certain regions of the country. Insights drawn from these population-level baseline estimates provide directions for future research in this population that has been conspicuously absent in the literature to date. They also serve as a call to action for mental health providers, health systems, Medicare program officials, and policy makers at the federal, state, and local level to develop policies and interventions for improving the management of fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries with schizophrenia, particularly in regions where outcomes are significantly worse than average.

Transparency

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study design and concept, data analysis and review, data interpretation, and manuscript review.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have received an honorarium from JME for their review work but have no other relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Excel (2 MB)Acknowledgements

None reported.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

PL, ZG: Nothing to disclose; CB, SS, CP: Employees of Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC; JAD: Consultancy for AbbVie, Acadia, Allergan, Janssen, Merck, Otsuka, and Takeda; research funding from Janssen, Merck, Regeneron, and Spark Therapeutics.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions.

Correction Statement

This article was originally published with errors, which have now been corrected in the online version. Please see Correction (http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13696998.2023.2265633)

Additional information

Funding

References

- National Institute of Mental Health. Schizophrenia. National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). [cited 2023 Jan 26]. n.d. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/schizophrenia.

- De Berardis D, De Filippis S, Masi G, et al. A neurodevelopment approach for a transitional model of early onset schizophrenia. Brain Sci. 2021;11:275.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5TM. 5th ed. Arlington (VA): American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2013.

- Regier D, Narrow W, Rae D, et al. The de facto US mental and addictive disorders service system. Epidemiologic catchment area prospective 1-year prevalence rates of disorders and services. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50(2):85–94.

- McGrath J, Saha S, Chant D, et al. Schizophrenia: a concise overview of incidence, prevalence, and mortality. Epidemiol Rev. 2008;30:67–76.

- Desai PR, Lawson KA, Barner JC, et al. Estimating the direct and indirect costs for community-dwelling patients with schizophrenia. J Pharm Health Serv Res. 2013;4:187–194.

- Olfson M, Gerhard T, Huang C, et al. Premature mortality among adults with schizophrenia in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(12):1172–1181.

- Schoenbaum M, Sutherland JM, Chappel A, et al. Twelve-month health care use and mortality in commercially insured young people with incident psychosis in the United States. Schizophr Bull. 2017;43(6):1262–1272.

- Simon GE, Stewart C, Yarborough BJ, et al. Mortality rates after the first diagnosis of psychotic disorder in adolescents and young adults. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(3):254–260.

- Kadakia A, Catillon M, Fan Q, et al. The economic burden of schizophrenia in the United States. J Clin Psychiatry. 2022;83:22m14458.

- Byerly MJ, Nakonezny PA, Lescouflair E. Antipsychotic medication adherence in schizophrenia. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2007;30:437–452.

- Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, et al. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(12):1209–1223.

- Higashi K, Medic G, Littlewood KJ, et al. Medication adherence in schizophrenia: factors influencing adherence and consequences of nonadherence, a systematic literature review. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2013;3(4):200–218.

- Olivares JM, Sermon J, Hemels M, et al. Definitions and drivers of relapse in patients with schizophrenia: a systematic literature review. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2013;12:32.

- Gilmer TP, Dolder CR, Lacro JP, et al. Adherence to treatment with antipsychotic medication and health care costs among Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(4):692–699.

- Ascher-Svanum H, Faries DE, Zhu B, et al. Medication adherence and long-term functional outcomes in the treatment of schizophrenia in usual care. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(3):453–460.

- Correll CU, Citrome L, Haddad PM, et al. The use of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in schizophrenia: evaluating the evidence. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(suppl 3):1–24.

- Velligan DI, Weiden PJ, Sajatovic M, et al. Strategies for addressing adherence problems in patients with serious and persistent mental illness: recommendations from the expert consensus guidelines. J Psychiatr Pract. 2010;16(5):306–324.

- West JC, Marcus SC, Wilk J, et al. Use of depot antipsychotic medications for medication nonadherence in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34(5):995–1001.

- Yeo V, Dowsey M, Alguera-Lara V, et al. Antipsychotic choice: understanding shared decision-making among doctors and patients. J Ment Health. 2021;30(1):66–73.

- Marcus SC, Zummo J, Pettit AR, et al. Antipsychotic adherence and rehospitalization in schizophrenia patients receiving oral versus long-acting injectable antipsychotics following hospital discharge. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2015;21(9):754–768.

- Lafeuille M-H, Grittner AM, Fortier J, et al. Comparison of rehospitalization rates and associated costs among patients with schizophrenia receiving paliperidone palmitate or oral antipsychotics. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2015;72(5):378–389.

- Pilon D, Tandon N, Lafeuille M, et al. Treatment patterns, health care resource utilization, and spending in medicaid beneficiaries initiating second-generation long-acting injectable agents versus oral atypical antipsychotics. Clin Ther. 2017;39(10):1972–1985.e2.

- Taipale H, Mehtälä J, Tanskanen A, et al. Comparative effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs for rehospitalization in Schizophrenia-a nationwide study with 20-year follow-up. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44(6):1381–1387.

- Taipale H, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Alexanderson K, et al. Antipsychotics and mortality in a nationwide cohort of 29,823 patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2018;197:274–280.

- Tiihonen J, Haukka J, Taylor M, et al. A nationwide cohort study of oral and depot antipsychotics after first hospitalization for schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:603–609.

- Tiihonen J, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Majak M, et al. Real-world effectiveness of antipsychotic treatments in a nationwide cohort of 29 823 patients with schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74:686–693.

- Kishimoto T, Nitta M, Borenstein M, et al. Long-acting injectable versus oral antipsychotics in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of mirror-image studies. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74:957–965.

- Kishimoto T, Hagi K, Nitta M, et al. Effectiveness of long-acting injectable vs oral antipsychotics in patients with schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of prospective and retrospective cohort studies. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44:603–619.

- Brown JD, Barrett A, Caffery E, et al. State and demographic variation in use of depot antipsychotics by Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65:121–124.

- Lawson W, Johnston S, Karson C, et al. Racial differences in antipsychotic use: claims database analysis of Medicaid-insured patients with schizophrenia. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2015;27:242–252.

- Sultana J, Hurtado I, Bejarano-Quisoboni D, et al. Antipsychotic utilization patterns among patients with schizophrenic disorder: a cross-national analysis in four countries. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2019;75:1005–1015.

- Patel C, Emond B, Morrison L, et al. Risk of subsequent relapses and corresponding healthcare costs among recently-relapsed Medicaid patients with schizophrenia: a real-world retrospective cohort study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2021;37:665–674.

- Sun SX, Liu GG, Christensen DB, et al. Review and analysis of hospitalization costs associated with antipsychotic nonadherence in the treatment of schizophrenia in the United States. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23:2305–2312.

- Nicholl D, Akhras KS, Diels J, et al. Burden of schizophrenia in recently diagnosed patients: healthcare utilisation and cost perspective. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26:943–955.

- Horvitz-Lennon M, Volya R, Donohue JM, et al. Disparities in quality of care among publicly insured adults with schizophrenia in four large U.S. states, 2002-2008. Health Serv Res. 2014;49:1121–1144.

- Olfson M, Marcus SC, Doshi JA. Continuity of care after inpatient discharge of patients with schizophrenia in the Medicaid program: a retrospective longitudinal cohort analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:831–838.

- Patel C, Pilon D, Gupta D, et al. National and regional description of healthcare measures among adult Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia within the United States. J Med Econ. 2022;25:792–807.

- Khaykin E, Eaton WW, Ford DE, et al. Health insurance coverage among persons with schizophrenia in the United States. Psychiatric Serv. 2010;61:830–834.

- Zhang Y, Baik SH, Newhouse JP. Use of intelligent assignment to Medicare Part D plans for people with schizophrenia could produce substantial savings. Health Aff. 2015;34:455–460.

- Department of Health and Human Services. 45 CFR 46. HHS.Gov. 2016. [cited 2022 Dec 21]. https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/regulations/45-cfr-46/index.html.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Hospital quality initiative: measure methodology. 2021. [cited 2022 Dec 21]. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/HospitalQualityInits/Measure-Methodology.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Inpatient psychiatric facility quality reporting (IPFQR) program overview. n.d. [cited 2022 Dec 21]. https://qualitynet.cms.gov/ipf/ipfqr.

- National Committee for Quality Assurance. Adherence to antipsychotic medications for individuals with schizophrenia. NCQA. n.d. [cited 2023 Feb 23]. https://www.ncqa.org/hedis/measures/adherence-to-antipsychotic-medications-for-individuals-with-schizophrenia/.

- Peterson A, Nau D, Cramer J, et al. A checklist for medication compliance and persistence studies using retrospective databases. Value Health. 2007;10:3–12.

- Campagna EJ, Muser E, Parks J, et al. Methodological considerations in estimating adherence and persistence for a long-acting injectable medication. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2014;20:756–766.

- Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, et al. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36:8–27.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Elixhauser comorbidity software, version 3.7. healthcare cost and utilization project (HCUP). 2017. [cited 2023 Feb 9]. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/comorbidity/comorbidity.jsp.

- Glick HA, Doshi JA, Sonnad SS, Polsky D, editors. Economic evaluation in clinical trials. 2nd ed. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press; 2014.

- SAS Institute. SAS: analytics, artificial intelligence and data management. 2022. [cited 2022 Dec 21]. https://www.sas.com/en_us/home.html.

- Laursen TM, Nordentoft M, Mortensen PB. Excess early mortality in schizophrenia. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2014;10:425–448.

- Li P, Benson C, Geng Z, et al. Out-of-pocket costs for long-acting injectable and oral antipsychotics by low-income subsidy status of Medicare part D beneficiaries with schizophrenia. Presented at: American Society of Health-System Pharmacists 2022 Midyear Clinical Meeting and Exhibition; December 4-8, 2022; Las Vegas, NV. Poster 8-130.

- Keepers GA, Fochtmann LJ, Anzia JM, et al. The American psychiatric association practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177:868–872.

- Barnes TRE. Schizophrenia consensus group of British association for psychopharmacology. Evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of schizophrenia: recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2011;25:567–620.

- Buchanan RW, Kreyenbuhl J, Kelly DL, et al. The 2009 schizophrenia PORT psychopharmacological treatment recommendations and summary statements. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36:71–93.

- Galletly C, Castle D, Dark F, et al. Royal Australian and New Zealand college of psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for the management of schizophrenia and related disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2016;50:410–472.

- Hasan A, Falkai P, Wobrock T, et al. World federation of societies of biological psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for biological treatment of schizophrenia, part 1: update 2012 on the acute treatment of schizophrenia and the management of treatment resistance. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2012;13:318–378.

- National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (UK). Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: treatment and management. Updated ed. 2014. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK); 2014.

- Remington G, Addington D, Honer W, et al. Guidelines for the pharmacotherapy of schizophrenia in adults. Can J Psychiatry. 2017;62:604–616.

- Hamann J, Kissling W, Heres S. Checking the plausibility of psychiatrists׳ arguments for not prescribing depot medication. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;24(9):1506–1510.

- Heres S, Hamann J, Kissling W, et al. Attitudes of psychiatrists toward antipsychotic depot medication. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(12):1948–1953.

- Kirschner M, Theodoridou A, Fusar-Poli P, et al. Patients’ and clinicians’ attitude towards long-acting depot antipsychotics in subjects with a first episode of psychosis. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2013;3:89–99.

- Galewitz P. Uber and Lyft ride-sharing services hitch onto Medicaid. Kaiser Health News; 2019. [cited 2023 Feb 8]. https://khn.org/news/uber-and-lyft-hitch-onto-medicaid/.

- National Council for Mental Wellbeing. CCBHC Locator. National Council for Mental Wellbeing 2021. [cited 2022 Dec 21]. https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/program/ccbhc-success-center/ccbhc-overview/ccbhc-locator/.

- National Alliance of State Pharmacy Associations. Pharmacist authority to administer long-acting antipsychotics. n.d. [cited 2022 Dec 21]. https://naspa.us/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Pharmacists-Authority-to-Administer-Medications.pdf.

- Murugappan MN, Seifert RD, Farley JF. Examining Medicare Part D medication therapy management program in the context of mental health. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2020;60:571–579.e1.

- Yarmuth, JA. H.R.5376 - 117th Congress (2021-2022): Inflation Reduction Act of 2022. 2022. [cited 2022 Dec 20]. http://www.congress.gov/.