Background

Clinical validation is a critical step for any health economic (HE) modeling analysis and is often required (or at least highly suggested) by health technology assessment agencies.Citation1,Citation2 Clinical validation can also play a role in early value assessment. As HE models are increasingly developed to support provisional value propositions, clinical validation can help to provide a solid foundation for decisions made in the early product lifecycle.Citation3 Additionally, a description of model validation methods should be included as part of health technology assessment reporting, according to the most recent statement by the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) and ISPOR-SMDM.Citation4,Citation5

As part of the clinical validation process, HE model inputs, treatment pathway, assumptions, and results are evaluated by clinical experts and key opinion leaders (KOLs) to confirm the clinical relevance and/or validity of the conceptual framework or content of the model, also considered a part of the face validity evaluation.Citation5 Guidelines suggest that five elements of an HE model should be validated: 1) problem formulation, 2) model structure, 3) data sources, 4) assumptions, and in some cases, 5) results.Citation1,Citation5 However, these guidelines do not recommend specific timing for the costly and time-consuming consultations required to obtain validation from outside experts. Additionally, the rigor or thoroughness of the clinical validation process are rarely discussed. For example, the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) advises the consultation should be done early and iteratively over the course of HE model developmentCitation1 but no specific suggestion is provided on when or how to ask questions to clinical experts, who are generally not familiar with HE concepts.

While the literature lacks reviews of common problems that arise during clinical validation of an HE model, we generally find that clinical validation is not timed properly, not effective at filling all the gaps, or not done at all. Using the wrong clinical validation strategy will limit the inferences that can be drawn from KOLs. The result is data gaps that are not addressed or assumptions that are not properly supported.Citation6 This editorial defines a stepwise approach to clinical validation of HE models. The proposed framework provides guidance on the timing, format, and types of questions that should be proposed to KOLs throughout the validation process. It was developed through a literature review and the experience of the authors coordinating the validation of HE models. We limited our search to sources with substantial, focused guidance on clinical validation of HE models, and therefore our findings did not include articles with more general recommendations for HE model design.

Results of the literature review

The results of the literature review are presented in . Previous guidelines and studies have considered face validity as a necessary part of HE-model validation and recommend that it be started early and iteratively throughout model development.Citation1 However, there is no consensus on what type of expert should be consulted. Eddy et al. suggest that clinical experts be involved in the validation process while CADTH recommends engaging “content experts”. Two studies use the term “expert” with no mention of clinical knowledge.Citation8,Citation9

Table 1. The face validity of HE models in published guidelines or articles.

There is general agreement that face validation of HE models should involve three main phases: model structure, model inputs (assumptions and data), and results. A few general and specific questions focused on validation of HE models were provided.

Philips et al.Citation9 provide more details on how to involve experts in the model validation; if group interviews are preferred, five to eight KOLs should be selected from different practice setting in various geographical locations. While Philips and colleagues recommend Delphi panels for consultation with clinical experts, particularly when consensus is desired for low-information topics, interviews or surveys have also been described as a preferred approachCitation1,Citation5,Citation10 given that face validity is subjective and clinical validation necessitates a qualitative process.

A framework for clinical validation of HE models

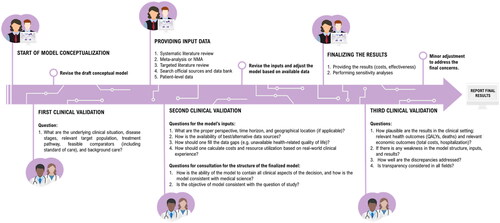

Clinical validation is a time-consuming and expensive but critical task. In this section, we provide a framework for consultation with KOLs during an economic evaluation (). Based on the need for expert guidance at several points during the process of model design and evaluation, we suggest that clinical validation take place in three phases:

Figure 1. A new time-oriented HE model-validation framework for the questions which should be proposed to clinical experts. Abbreviations. NMA, network meta-analysis; QALY, quality-adjusted life-year.

Phase 1: At the start of model design, the HE modeler should seek clinical validation of the conceptual framework, which captures the underlying disease and treatment pathway. This phase—also called first-order validation—attempts to evaluate whether the HE analysis can represent the medical condition being addressed.Citation10 At this stage, the KOL should be blind to any possible model results.

Phase 2: The second order of the clinical validation process should take place after the HE model has been constructed. At this time, the HE modelers should seek clinical validation on the model’s inputs. This can include data on health-related quality of life (e.g. utilities), transition probabilities, costs, and resource use. Key model assumptions should also be validated. A comprehensive review of the final model structure can also be conducted in this phase. Once again, the KOL should be blind to any possible model results.

Note, Phase 1 and Phase 2 are often pooled to limit the number of interactions with KOLs. While this is a less costly approach, three phases are recommended as it is more likely to capture all the necessary information related to the model’s conceptualization, methodology, and results.

Phase 3: The third order—and last phase—of clinical validation should be scheduled when the results of the model are available. The model’s results, which can be reported as quality-adjusted life years, costs, or length of survival, should be evaluated against clinical understanding. Other aspects of the model, such as the trace and extrapolation techniques, along with sensitivity analyses and pre-determined statistical tests, can be also validated at this time.

According to our literature review, modified Delphi panels with a steering committee are considered the best practice to engage KOLs in the validation process as they are designed to develop consensus when there is little or no definitive evidence available.Citation7,Citation11 Based on the authors’ experience, three to five clinical experts are suggested for a modified Delphi approach to best address any disagreement to reach a final consensus by the end of the session. This is substantially below the literature-recommended 30 to 50 experts,Citation11 which would be unfeasible in most HE-evaluation contexts. We would also note that many “Delphi approaches” presented in the literature often resemble more of a nominal group techniqueCitation12 due to the lack of anonymity and small number of experts (see Table 2 in Nasa et al.).Citation11 Nevertheless, organizing KOLs in the group setting required for a modified Delphi panel may be challenging due to time and financial constraints.

Traditional Delphi panels can prove helpful when modified Delphi panels are not feasible since they do not rely on synchronicity. As another alternative, we recommend semi-structured, one-on-one interviews with KOLs via phone or video as another, more practical, option. In a semi-structured interview, the list of questions and probes are prepared in advance, but time is allotted for additional questions that may arise during the interview itself.Citation13 Semi-structured interviews are often considered “the best of both worlds” as they combine elements of structured and unstructured interviews to ensure comparable data across interviews with the flexibility to ask follow-up questions and spontaneously explore relevant topics.

In our experience, the results of semi-structured interviews can be improved by the careful preparation of interview materials and communications. Examples of appropriate questions are provided by several sources identified in the literature review (). Any directional or anchored questions should be reviewed thoroughly to ensure they are not introducing significant interviewer bias. In situations where a question may be difficult for a KOL to answer, an evidenced-based example can be provided. It can be based on data on file or published literature, such as HTA reviews or real-world evidence. This example will provide some guidance to the KOL and an anchor to use when formulating their response. It will reduce the amount of missing data (e.g. if the KOL otherwise felt unable or uncomfortable to answer a question) and encourage the KOL to provide more precise information that can be operationalized in the model (i.e. by focusing the discussion around a specific estimate instead of a range of possible values). Background information and the list of questions may be sent to the KOL in advance of the interview.

If individual phone or video interviews are not feasible, a questionnaire can be distributed by email. The first round of emails would contain the background information and a list of closed-ended questions, with binned ranges for quantitative responses. It is important to avoid open-ended questions in this context. The second round of emails would contain the KOL’s answers with follow-up questions and requests for clarification (if applicable). KOLs should be asked to review and, if necessary, modify their answers for the last time.

Regardless of the method (Delphi, interview, questionnaire), KOLs should be selected in consideration of the country-specific perspective of the HE analysis (e.g. if the model has a UK payer perspective, the experience of clinicians practicing in the UK should be prioritized in KOL selection). Additionally, KOLs from different practice settings and geographic locations can contribute to the generalizability of model findings.

Another important factor is the documentation of the clinical validation process and findings. The questions posed to the KOLs, their individual answers, and the aggregated analysis should be available to health technology assessment agencies, payers, and model reviewers if needed. Many reports will simply reference “data on file” or “expert opinion.” More transparent documentation is required to avoid misleading or potentially wrong referencing approaches. At a minimum, the interviews should be recorded and the following information documented: interviewer name and affiliation, date of interview, clinical speciality of the KOL, location of practice, objective of interview, list of questions, detailed notes on the answers to individual questions, and aggregated analysis of findings across interviews. This is necessary to ensure the validity and replicability of the validation process. Permission to retain recordings can be obtained after informing KOLs of data sharing policies and providing a list of potential parties who may have access to the recording in the future.

Discussion

An HE model must be technically correct, but also clinically relevant. It is widely accepted that HE models require clinical validation. This should be considered an iterative process, where KOLs are consulted in a systematic and structured manner during three phases of model development: at the conceptual framework stage, after the first draft of the model has been developed, and once the results are available. However, specific guidance on the clinical validation process is lacking. To our knowledge, this is the first attempt at developing a specific stepwise approach for the clinical validation of HE models. This process could also be applied to comparative effectiveness research, including network meta-analyses and matching-adjusted indirect comparisons.

One limitation of our proposed clinical validation approach is clear: because there are very few publications on the subject, little is known on the effectiveness of Delphi panels or targeted interviews for HE clinical validation. Our concept is therefore based on a qualitative assessment that takes into account published best practices as well as practical considerations based on the experiences of the authors in conducting HE clinical validation. Further research, including the development of alternative consensus approaches, should be developed to aid investigators in navigating the use of KOL feedback for model validation. The suggested efforts to maximize data transparency would facilitate methodological comparisons of the recommended three-phase approach in the HE context, which could help validate the proposed framework.

Transparency

Declaration of financial/other relationships

GT is an employee of Cytel Inc, and BH was an employee of Cytel Inc at the time of manuscript writing.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgements

None reported.

Data availability statement

None.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Health Economics Working Group. Guidelines for the economic evaluation of health technologies: Canada. Canada: CADTH (Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health); 2017.

- Haute Autorité de Santé. Choices in methods for economic evaluation. Department of Economics and Public Health Assessment; 2012.

- IJzerman MJ, Koffijberg H, Fenwick E, et al. Emerging use of early health technology assessment in medical product development: a scoping review of the literature. PharmacoEconomics. 2017;35(7):727–740.

- Husereau D, Drummond M, Augustovski F, et al. Consolidated health economic evaluation reporting standards 2022 (CHEERS 2022) statement: updated reporting guidance for health economic evaluations. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2022;20(2):213–221.

- Eddy DM, Hollingworth W, Caro JJ, et al. Model transparency and validation: a report of the ISPOR-SMDM modeling good research practices task force-7. Med Dec Mak Inter J Soc Med Dec Making. 2012;32(5):733–743.

- Frederix GWJ. Check your checklist: the danger of over- and underestimating the quality of economic evaluations. PharmacoEconomics Open. 2019;3:433–435.

- Philips Z, Ginnelly L, Sculpher M, et al. Review of guidelines for good practice in decision-analytic modelling in health technology assessment. Health Technol Assess. 2004;8(36):1–158.

- Caro J, Eddy DM, Kan H, et al. Questionnaire to assess relevance and credibility of modeling studies for informing health care decision making: an ISPOR-AMCP-NPC good practice task force report. Value Health J Inter Soc Pharmacoeconomics Outcomes Res. 2014;17(2):174–182.

- Vemer P, Corro Ramos I, van Voorn GA, et al. AdViSHE: a Validation-Assessment tool of Health-Economic models for decision makers and model users. PharmacoEconomics. 2016;34(4):349–361.

- McHaney R. Computer simulation: a practical perspective. San Diego, CA: Academic Press, Inc.; 1991.

- Nasa P, Jain RDJ. Delphi methodology in healthcare research: how to decide its appropriateness. World J Methodol. 2021;11(4):116–129.

- McMillan SS, King M, Tully MP. How to use the nominal group and delphi techniques. Inter J Clin Pharm. 2016;38(3):655–662.

- DiCicco-Bloom B, Crabtree BF. The qualitative research interview. Med Educ. 2006;40(4):314–321.