?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Aims

Despite migraine being one of the most common neurological diseases, affected patients are often not effectively treated. This analysis describes the burden of migraine in Germany and assesses real-world treatment patterns and healthcare resource utilization (HCRU) of preventive-treated migraine patients from the perspective of Statutory Health Insurance.

Methods

A retrospective analysis was conducted using InGef Research Database claims data from 2018–2019. Migraine patients were stratified into cohorts by acute and preventive treatment status. Patients on preventive treatment were further stratified according to the type of prophylaxis received. Disease burden in preventively treated migraine patients was reported via treatment patterns, pathways, and comorbidities. HCRU was assessed through outpatient provider visits, hospitalizations, and sick leave.

Results

160,164 adult migraine patients were identified, of which 55,378 (34.6%) were prescribed preventive treatment with conventional (n = 25,984, 46.9%), calcitonin gene-related peptide monoclonal antibody (CGRP mAb) (n = 613, 1.1%), or off-label therapies (n = 28,781, 52.0%). 936 (1.7%) patients received Botulinum Neurotoxin Type A (BoNTA). CGRP mAb-treated patients had a high rate of triptan prescriptions (2018: 95.5%; 2019: 88.9%), migraine-related hospitalizations (2018: 33.0%; 2019: 21.0%), and sick leave (2018: 26.8%; 2019: 22.5%). A high proportion of CGRP mAb- and BoNTA-treated patients was diagnosed with abdominal and pelvic pain (34.3% and 36.2%) and low back pain (34.1% and 35.3%). These patients also showed a high prevalence of depressive episodes (49.1% and 50.1%) and chronic pain disorders (37.5% and 32.9%).

Limitations

This study focused on descriptive analyses which do not allow for assessment of causality when comparing treatment groups.

Conclusions

Disease burden was high in patients receiving CGRP mAbs suggesting that patients treated preventively with CGRP mAbs shortly after product launch in Germany were severely affected, chronic migraine patients. The same may be true for patients receiving BoNTA who also showed an increased disease burden.

Introduction

Migraine headaches are one of the most common neurological diseases with a one-year prevalence between 10% and 15%, and a higher prevalence in females compared to malesCitation1. The Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 reported migraine as the leading cause of disability in young women and the second leading cause of years lived with disability worldwideCitation2. Studies have also shown high productivity losses and high financial burdens due to migraineCitation3–7.

Despite the high prevalence of migraine and the availability of evidence-based nationalCitation1 and internationalCitation8 guidelines, evidence indicates that patients are often under-recognized, under-diagnosed, and under-treatedCitation9–13. About 80% of migraine patients treat their headaches with acute treatments including analgesics or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), which can be purchased over the counter (OTC)Citation1,Citation14. For patients who respond inadequately or suffer from moderate to moderate-severe attacks, triptans are available as a specific acute treatment for migraineCitation1.

Patients that have severe symptoms need preventive treatment to reduce the frequency, severity, and duration of migraine attacksCitation1. Currently, the approved migraine preventive treatments available in Germany, which include the beta-receptor blockers propranolol and metoprolol, the calcium antagonist flunarizine, the anticonvulsants valproic acidFootnotei and topiramate, and the tricyclic antidepressant amitriptyline, are effective in many patients. In addition, other off-label preventive treatment options are in use (e.g. other beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, other tricyclic antidepressants)Citation1. In general, evidence suggests that undesirable side effects could lead to low adherence and persistence of preventive medications for migraineCitation15–17.

Botulinum Neurotoxin Type A (BoNTA) is a treatment option for symptom relief in adult patients with chronic migraine who respond inadequately to preventive medication. BoNTA received regulatory approval in Germany in 2011 because it was shown to be an effective and safe treatment for chronic migraine in the Phase 3 REsearch Evaluating Migraine Prophylaxis Therapy (PREEMPT) clinical trialsCitation18–21. Recently, several comprehensive clinical studies have shown monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) targeting the calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) or CGRP receptor to be effective in migraine prophylaxisCitation22. ErenumabCitation23, galcanezumabCitation24, and fremanezumabCitation25 have been approved for preventive treatment of migraine in adults and are reimbursed in Germany since November 2018, April 2019, and May 2019, respectively. EptinezumabCitation26 was most recently approved in January 2022. At the time of study conduct, treatment with CGRP mAbs was reimbursed in Germany in patients with migraine on ≥4 days/months who have not responded to ≥4 of the conventional preventive medications (metoprolol, propranolol, flunarizine, topiramate, amitriptyline) or who cannot be treated with other preventive treatments due to contraindications or side effects. Patients, particularly those with chronic migraine (≥15 headache days/month, of which ≥8 days with migraine), may be prescribed CGRP mAbs if they have also failed to respond to treatment with BoNTACitation27. As of April 2022, erenumab can already be reimbursed for the treatment of patients with ≥4 migraine days/month when prior prophylaxis with metoprolol, propranolol, flunarizine, topiramate, amitriptyline, or BoNTA has not been effective, was not tolerated, or there are contraindications to all of the above agents. Regarding the use of the other CGRP mAbs, reimbursement guidelines remained unchangedCitation1.

The aim of this descriptive analysis was to describe the real-world pharmaceutical treatment patterns and healthcare resource utilization (HCRU) of preventive-treated migraine patients and to assess the corresponding disease burden from the perspective of the German Statutory Health Insurance (SHI).

Methods

Data source

This was a retrospective analysis using anonymized claims data from the “Institute for Applied Health Research Berlin” (InGef) Research Database, which includes about 4 million covered individuals and is structured to represent the German population in terms of age and sex. As of 2020, the database represents 4.8% of the German populationCitation28 and about 5.5% of the SHI populationCitation29. The InGef Research Database has been proven to have a high external validity to the German population in terms of morbidity, mortality, and drug useCitation30,Citation31. Sampling strategy, characteristics, and representativeness of the InGef Research Database are detailed in the recent publication by Ludwig et al. (2021)Citation31. Because the InGef Research Database complies with German privacy regulations and the use of anonymized secondary data is in accordance with national law, ethics committee approval was not required, and no waiver was received for this non-interventional study.

Patient and Cohort Identification

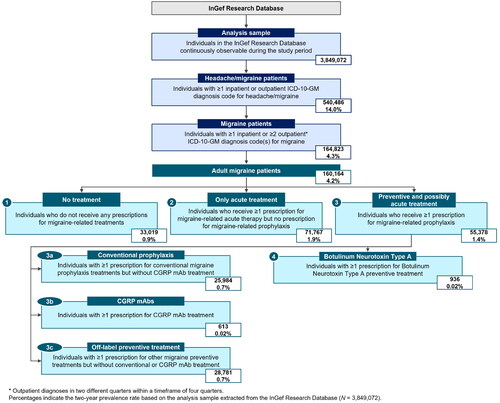

The study period was 1 January 2018 to 31 December 2019. The overall study population () consisted of all headache and migraine patients identified in the InGef Research Database who were continuously enrolled throughout the study period. Patient age and sex were recorded at data cutoff (31 December 2019). Patients were required to have ≥1 recorded headache and/or migraine diagnosis, based on the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, German Modification (ICD-10-GM) diagnosis codes G43, G44, or R51 (see Supplemental Table 1 for a complete list of ICD-10-GM codes used). Within this population, migraine patients were identified as those presenting with ≥1 migraine diagnosis (ICD-10-GM code G43) in the inpatient setting. Outpatient migraine diagnoses were considered if they met the M2Q criterion defined as the presence of ≥2 verified outpatient diagnosis records of G43 in two different quarters within a timeframe of four quartersCitation32.

Based on Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification (ATC) System (Supplemental Table 2) and German Central Pharmaceutical Number (PZN) codes (Supplemental Table 3), adult migraine patients were stratified into the following treatment cohorts.

Cohort 1: Adult migraine patients who did not receive any prescriptions for migraine-related treatments (acute or preventive) at the expense of the SHI.

Cohort 2: Adult migraine patients who had received ≥1 prescription for migraine-related acute therapy, but did not present with any prescriptions for migraine-related prophylaxis.

Cohort 3: Adult migraine patients receiving ≥1 prescription for migraine-related prophylaxis and potentially also receiving migraine-related acute therapy.

Patients in Cohort 3 were further stratified according to the type of prophylaxis received. The stratification led into distinct treatment Cohorts 3a, 3b, and 3c as described in the following. Cohort 3a included those treated with conventional migraine preventive treatment (metoprolol, propranolol, flunarizine, topiramate, amitriptyline). Patients receiving BoNTA were also included, while those taking CGRP mAbs were not included in this sub-cohort. However, additional acute treatments and off-label preventives were not exclusion criteria for this cohort.

Since the prescription of CGRP mAbs is only recommended for patients who do not respond to, are unsuitable for, or do not tolerate conventional migraine preventive medicationCitation1, Cohort 3b included those receiving CGRP mAbs (erenumab, galcanezumab, or fremanezumab). Patients also receiving acute treatments and conventional or off-label preventives were included in this sub-cohort.

Cohort 3c included patients treated with unconventional or off-label migraine preventive treatment. Patients also taking acute treatments were included, while those receiving conventional preventive medication or CGRP mAbs were excluded from this sub-cohort.

Additionally, a sensitivity analysis included all patients from Cohort 3 that received treatment with BoNTA (Cohort 4).

Outcomes

The primary objective was to descriptively report the disease burden of migraine in patients who were preventively treated by describing treatment patterns, pathways, and comorbidities. HCRU was assessed including outpatient provider visits, hospitalizations, and sick leave. A complete list of ICD-10-GM codes and codes from the Official German Remuneration Scheme for Outpatient Care (Einheitlicher Bewertungsmaßstab – EBM) used to identify all considered outcomes is provided in the Supplemental Table 4.

Treatment patterns and pathways

Treatment patterns were assessed for the years 2018 and 2019. Patients were stratified by acute treatment (triptans, non-triptans) and prophylaxis (conventional preventive treatment, CGRP mAbs, off-label preventive treatments) (Supplemental Table 2 and Supplemental Table 3). To avoid including patients taking non-triptans for other indications, only prescriptions where a headache (G44 and/or R51) and/or migraine (G43) ICD-10-GM diagnosis was documented by the same physician in the same quarter were considered.

Throughout the study period, treatment pathways depicting initiation, switch, or discontinuation of migraine preventive medications were described in patients of Cohort 3 and the corresponding sub-cohort 3b (CGRP mAbs). The number of patients continuing, switching, or discontinuing their current prophylaxis was counted for each quarterly transition of the study period (Q1/2018 – Q4/2019). Sankey plots visualizing treatment pathways are depicted in Supplemental Table 5.

Comorbidities

Pre-selected comorbidities of special interest were derived from scientific literature and in consultation with medical experts. These comorbidities include obesity, insomnia, hypertension, osteoarthritis, back pain, and several mental and behavioral disorders (see Supplemental Table 4 for a complete list of analyzed comorbidities). For patients in Cohort 3 and its corresponding sub-cohorts, comorbidities with ≥1 recorded inpatient (primary and secondary diagnoses) or outpatient (verified diagnoses) ICD-10-GM code (Supplemental Table 4) during the study period were identified.

Healthcare resource utilization

Annual HCRU was determined for the years 2018 and 2019 for patients in Cohort 3 and its respective sub-cohorts. For this purpose, the study cohorts were stratified into two separate annual sub-cohorts for 2018 and 2019. In accordance with the hierarchy CGRP mAb > conventional treatment > off-label treatment described in the section “Patient and Cohort Identification”, patients were considered in the year in which they received treatment at the highest hierarchy level - e.g. a patient receiving conventional preventive treatment in 2018 and CGRP mAb treatment in 2019 was only included in the analysis for 2019 as part of the CGRP mAb treatment cohort.

Outpatient provider visits:

All-cause outpatient provider visits were identified by each date with a recorded EBM code requiring any kind of physician specialty contacts. Migraine-related outpatient provider visits were identified by each date with a recorded EBM code, where a verified diagnosis of migraine (ICD-10-GM G43) was documented within the same quarter of the consultation and stratified by physician specialty. General practitioners, neurologists, and orthopedists were identified based on corresponding specialist groupsCitation33. Physicians with additional qualifications for pain therapy are further referred to as pain specialists. A specialization for pain therapy could be identified by special EBM billing codes according to the “Quality Assurance Agreement on Pain Therapy for Patients with Chronic Pain”Citation34 (Supplemental Table 4).

Hospitalizations:

All-cause hospitalizations included all hospitalizations occurring regardless of recorded diagnoses. Migraine-related hospitalizations including the ICD-10-GM G43 diagnosis as an admission or primary or secondary inpatient code were recorded. Length of stay (LOS) was assessed for all identified all-cause and migraine-related hospitalizations using the formula:

Sick leave:

All-cause sick leave included all sick leaves occurring regardless of recorded diagnoses. Migraine-related sick leave was identified by a migraine diagnosis (ICD-10-GM G43). The number of days of all-cause and migraine-related sick leave was assessed based on the start and the end date of the sick leave by calculating

Results

Study cohorts

Among the 3,849,072 continuously observable individuals in the InGef Research Database during the study period, 540,486 patients (14.0%) presented with a headache or migraine diagnosis. Of this population, 164,823 patients (30.5%) presented with migraine, corresponding to a two-year prevalence rate of 4.3%. The study's restriction to adult patients resulted in 160,164 adult migraine patients, of which 20.6% (N = 33,019) did not receive migraine treatment charged to the SHI (Cohort 1), 44.8% (N = 71,767) had prescriptions for acute treatment only (Cohort 2), and 34.6% (N = 55,378) were prescribed preventive and possibly acute treatment (Cohort 3).

Among patients in Cohort 3, 46.9% (n = 25,984) received conventional preventive treatment (Cohort 3a), 1.1% (n = 613) started treatment with CGRP mAbs (Cohort 3b), and 52.0% (n = 28,781) had prescriptions for off-label preventive medications (Cohort 3c). Additionally, 1.7% (n = 936) were treated with BoNTA (Cohort 4) ().

Patient demographics

Females comprised 65% of the headache/migraine population (N = 540,486) and 78% of migraine patients (N = 160,164). Of the patients receiving preventive treatment (Cohort 3), more than 80% were female.

Migraine patients had a mean (standard deviation [SD]) age of 47.9 (17.7) years, while headache/migraine patients were 42.8 (20.0) years on average. Patients receiving preventive treatment (Cohort 3) had a mean age of 57.0 (15.8) years. Among preventively treated patients, those treated with CGRP mAbs (Cohort 3b) were 48.4 (12.0) years on average and patients treated with BoNTA (Cohort 4) had a mean age of 50.2 (13.6) years.

Overall, male patients had a lower mean age than female patients except for patients treated with BoNTA (Cohort 4). Further details on age and sex distribution can be found in Supplemental Table 6.

Treatment patterns and pathways

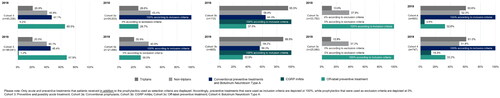

Patterns of acute migraine treatment

About half (51.1%) of patients in Cohort 3 received prescriptions for acute treatment in addition to preventive treatments (), with an average of 4.1 prescriptions per patient per year (Supplemental Table 7). Most patients in Cohort 3b (95%) had prescriptions for triptans, with 9.8 (6.6) prescriptions in 2018 and 7.5 (6.4) prescriptions in 2019. On the other hand, 27% of patients in Cohort 3a and 21% of patients in Cohort 3c had prescriptions for triptans (average of 4.2 and 3.0 prescriptions per year, respectively). In Cohort 4 (receiving BoNTA), 60% of patients received approximately 7 prescriptions for triptans in each year.

Patterns of preventive migraine treatment

Off-label preventive treatments were the most common treatments among patients taking preventive therapy in Cohort 3 (2018: 65.5%, 2019: 67.9%) (). An average of 3.6 (2.6) and 3.8 (2.6) prescriptions for off-label preventive treatments were filled in 2018 and 2019, respectively (Supplemental Table 7). Preventively treated patients in Cohort 3 received an average of 3.5 prescriptions for conventional preventive treatments in 2018 and 2019, representing 47.1% and 45.4% of the cohort, respectively. Prescriptions for CGRP mAbs were seen in 0.2% of Cohort 3 patients in 2018 and 1.2% in 2019. Regarding the number of prescriptions for CGRP mAbs, patients in Cohort 3b had a mean of 1.6 (0.6) prescriptions in 2018 and 4.2 (2.4) prescriptions in 2019. Cohort 3b also had prescriptions for conventional prophylaxis (64.3%) and/or off-label preventive treatments (37.5%) in 2018. Similar numbers were seen in 2019, with 56.2% and 32.9% of Cohort 3b patients having prescriptions for conventional prophylaxis and/or off-label preventive treatments, respectively. Among patients treated with BoNTA (Cohort 4), the proportion of patients receiving CGRP mAbs was 5.6% in 2018 and 14.3% in 2019. Patients in Cohort 4 had on average 1.5 (0.6) prescriptions in 2018 and 3.4 (2.1) prescriptions in 2019 for CGRP mAbs.

Treatment pathways

In Q1 2018, 18% of patients in Cohort 3 were on conventional preventive treatment, and 24.4% of patients were on off-label preventive treatment. This initial distribution remained consistent through Q4 2019, as most patients continued their initiated conventional or off-label preventive treatment until the end of the analysis period.

When looking at Cohort 3b, 18.3% of patients started therapy with CGRP mAbs shortly after the market launch in Q4 2018. By Q4 2019, 91.8% of patients in Cohort 3b and 1.0% of all preventive-treated patients in Cohort 3 received prophylaxis with CGRP mAbs. Most patients who initiated treatment with a CGRP mAb (Cohort 3b) were previously treated with conventional preventive treatments, and many patients received conventional preventive medication alongside their CGRP mAb treatment.

Treatment switching between conventional and off-label preventive treatments was the most common change in treatment (up to 2.9% of patients per quarter), and about one-fifth of all preventive-treated patients in Cohort 3 discontinued their treatment in Q4 2019. However, treatment switching or discontinuation after initiating a CGRP mAb was rare.

Comorbidities

Patients in Cohort 3 suffered most frequently from hypertension (68.4%), followed by lower back pain (65.8%) and lipometabolic disorders (41.5%). Among patients receiving CGRP mAbs (Cohort 3b) or BoNTA (Cohort 4), the proportion of patients who had abdominal and pelvic pain (34.3% and 36.2%, respectively) and lower back pain (34.1% and 35.3%, respectively) was high.

Depressive episodes (43.4%), somatoform disorders (39.8%), and other anxiety disorders (23.4%) were found to be the most prevalent psychiatric comorbidities (ICD-10-GM F diagnoses) among all preventive-treated patients in Cohort 3. Patients in Cohort 3b and Cohort 4 showed a high prevalence of depressive episodes (49.1% and 50.1%, respectively), chronic pain disorders with somatic and psychological factors (37.5% and 32.9%, respectively), recurrent depressive disorders (27.7% and 26.7%, respectively), persistent affective disorders (9.5%, and 8.9%, respectively) and abuse of non-psychoactive substances (10.4% and 9.0%, respectively). Further details on comorbidities of special interest can be found in Supplemental Table 8.

Healthcare resource utilization

Outpatient provider visits

Cohort 3 patients visited an outpatient physician on average 28.9 times per year, of which about one-third were migraine-related visits (2018: 10.4 (9.4) visits; 2019: 10.2 (8.8) visits) (). Patients receiving treatment with CGRP mAbs (Cohort 3b) averaged about five more all-cause (2018: 34.1 (21.4) visits; 2019: 32.6 (17.9) visits) and up to nine more migraine-related (2018: 19.7 (14.0) visits; 2019: 17.7 (10.2) visits) outpatient physician visits per year.

Table 1. Summary measures of all-cause and migraine-related outpatient provider visits.

The distribution of migraine-related outpatient provider visits stratified by physician specialty () showed, that about 80% of conventional (Cohort 3a) and off-label preventive-treated (Cohort 3c) patients visited a general practitioner due to migraine in 2018 and 2019. Among patients receiving CGRP mAbs (Cohort 3b), 96.4% (2018) and 90.4% (2019) had migraine-related general practitioner visits. Migraine-related visits to a neurologist occurred in 17% of patients in Cohort 3a and in 7% of patients in Cohort 3c. The corresponding percentages for visits to orthopedists were 2% vs 1%, and for visits to pain specialists 4% vs 1%, respectively.

Table 2. Summary measures of migraine-related outpatient specialist visits.

Of patients in Cohort 3b, about 60% had ≥1 neurologist visit with 6.0 (5.5) visits in 2018 and 3.9 (3.6) visits in 2019. Furthermore, orthopedists and pain specialists were frequently visited by patients of Cohort 3b (2018: 20.5%, 6.6 (3.6) visits; 2019: 19.0%, 6.2 (4.6) visits).

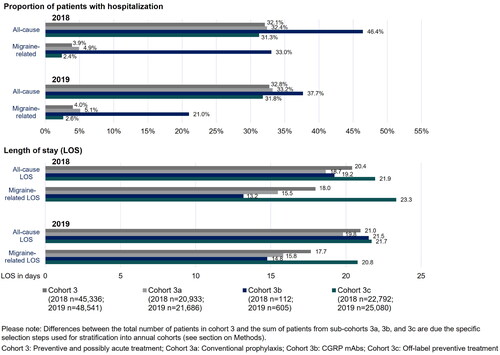

Hospitalizations

In 2018 and 2019, approximately 32% of all Cohort 3 patients had ≥1 admission to the hospital (). Of these, 4% were migraine-related hospitalizations. The proportion of patients with all-cause and migraine-related hospitalizations in conventionally treated patients (Cohort 3a) was slightly higher compared to patients with off-label preventive treatments (Cohort 3c). A high rate of hospitalizations was observed in patients receiving CGRP mAbs (Cohort 3b), where 46.6% had ≥1 hospitalization in 2018 and 37.7% in 2019. The proportion of patients in Cohort 3b with migraine-related hospitalizations was 33.0% in 2018 and 21.0% in 2019.

The LOS of patients with hospitalization varied between 20 and 22 days for all-cause hospitalizations and between 14 and 23 days for migraine-related inpatient stays. A long LOS of both all-cause (2018 and 2019: 22 days) and migraine-related (2018: 23 days; 2019: 21 days) hospitalizations was observed in patients in Cohort 3c. In contrast, migraine-related hospitalizations of patients receiving CGRP mAb prophylaxis (Cohort 3b) had a rather short LOS with about 13 days (2018) and 14 days (2019).

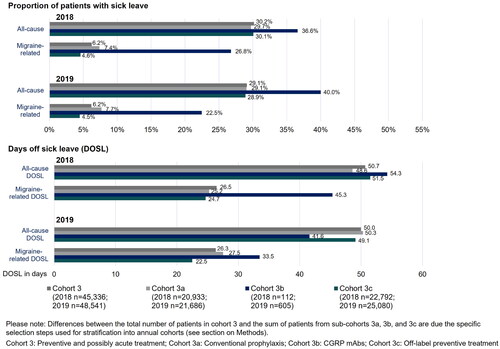

Sick leave

Approximately 30% of all patients in Cohort 3 had an average of 50 days of all-cause sick leave per year in 2018 and 2019 (). Migraine-related sick leaves occurred in about 6% of patients and averaged 26 days per year.

There were only slight differences in the proportion of patients with sick leave and the number of days of sick leave (DOSL) between conventional and off-label preventive-treated patients (Cohorts 3a and 3c). A high proportion of patients with all-cause (2018: 36.6%; 2019: 40.0%) and migraine-related (2018: 26.8%; 2019: 22.5%) sick leave were observed in patients receiving CGRP mAbs (Cohort 3b). Average DOSL for all-cause sick leave were 54.3 days and 41.6 days, and 45.3 days and 33.5 days for migraine-related sick leave in 2018 and 2019, respectively.

Discussion

This retrospective claims data analysis describes the disease burden of migraine and evaluates real-world treatment patterns and HCRU of preventively treated migraine patients in Germany. Results suggest a wide variety in migraine severity, with the most severely affected patients being preventively treated with CGRP mAbs or BoNTA.

Epidemiological findings on the number of migraine patients in Germany were largely consistent with previously published studies. Our analysis found a two-year rate of migraine of 4.3%, which is consistent with an increasing trend of migraine diagnoses reflected in an increase in reported migraine from 3.1% to 4.7% described in other claims data studies between 2012 and 2018Citation11,Citation35,Citation36. However, the results reported here differ from the 6-month prevalence of self-reported migraine of 7.2% from a 2016 German surveyCitation37, indicating that the prevalence of migraine in Germany might be higher than the reported values estimated based on claims data. Regarding the age and sex distribution, migraine patients in our analyses were on average 47.9 years old, and 78% of patients were female which is in line with findings of previous studiesCitation9,Citation11,Citation36,Citation38.

The results of this analysis indicate a large variation in the degree of migraine severity. Between 2018 and 2019, 20.6% of migraine patients did not receive any migraine-related treatment at the expense of the SHI (Cohort 1) and 44.8% had prescriptions for acute treatments only (Cohort 2). These patients might be individuals with mild to moderate migraines, which are treatable with analgesics, NSAIDs, or triptans, or patients who might be unwilling to use a preventive medication for other reasons. On the other hand, 34.6% of adult migraine patients received prescriptions for preventive treatments (Cohort 3), and of these, 21% were additionally treated with triptans in the same year, indicating that these patients have significantly more severe symptoms with the need for prophylaxis.

Stratification of patients in Cohort 3 according to preventive treatment revealed that most adult migraine patients (N = 160,164) received conventional (Cohort 3a: 16.2%) or only off-label preventive treatment (Cohort 3c: 18.0%). Given that BoNTA is approved only for adult patients with chronic migraine who respond inadequately to preventive medication, 0.6% (n = 936) of adult migraine patients in our analysis received ≥1 prescription for BoNTA in 2018 or 2019. This is consistent with findings of 0.8% of BoNTA prescriptions in 2016 as reported by Roessler et al.Citation11 and 0.5% of patients initiating preventive treatment with BoNTA in 2014 or 2015 as reported in Hardtstock et al.Citation38. Furthermore, 0.4% (n = 613) of adult migraine patients started treatment with CGRP mAbs between 2018 and 2019. When extrapolated to the entire German SHI population, this results in 11,634 [95% confidence interval 10,732–12,593] migraine patients who started treatment with a CGRP mAb. This is in line with data from the TK Headache Report, which reported a total of 10,765 insured persons in the SHI who had received a prescription for CGRP mAbs since their market launch through June 2019Citation36.

At the time of study conduct, initiation of treatment with CGRP mAbs in Germany was only reimbursed in patients with episodic (migraine-type headaches on up to 14 days/month) or chronic migraine (≥15 headache days/month, of which ≥8 days with migraine) who have failed ≥4 conventional preventive medicationsCitation27. This analysis showed that 64.3% of patients in 2018 and 56.2% in 2019 who initiated CGRP mAbs also received prescriptions for conventional preventive treatments. Analysis of treatment pathways indicated that more than 40% of patients who started CGRP mAb treatment had previously received ≥1 conventional preventive agent, and that a considerable proportion of patients started therapy with CGRP mAbs shortly after market launch. Thus, results suggest that these severely affected patients were already receiving late-line treatment before CGRP mAbs were approved but may have switched treatment due to dissatisfaction. However, the fact that many patients received conventional therapy alongside CGRP mAbs may suggest that CGRP mAb-treated patients are still difficult to treat. With the update of reimbursement guidelines for erenumab (see section “Introduction”) as of April 2022Citation1, further research of treatment pathways leading to initiation of prophylaxis with CGRP mAbs is warranted.

Prescriptions for triptans were observed frequently in patients receiving CGRP mAbs (2018: 95.5%, 2019: 88.9%) or BoNTA (2018: 60.6%, 2019: 61.0%) However, the analysis does not allow us to determine whether the prescription of triptans preceded or paralleled the prescription of CGRP mAbs/BoNTA. Nonetheless, the high proportion of triptan prescriptions may be attributed to the chronic and severe effect of migraines in these patients such that all other available preventive treatments may have already been exhausted – hence aligning with the indications for CGRP mAbs and BoNTA. Future studies may provide further insight into how migraine-related co-medications accompany the course of CGRP mAbs and BoNTA treatment.

The analysis of comorbidities indicated a high disease burden in CGRP mAb-initiating patients (Cohort 3b) and patients receiving BoNTA (Cohort 4). Diagnoses of abdominal and pelvic pain, lower back pain, depressive episodes, and recurrent depressive disorders were frequent in these sub-cohorts. These results align with the most commonly reported comorbidities in preventive-treated patients in the study by Hardtstock et al. Citation38. In general, literature on comorbidities of migraine patients confirms that such patients are often diagnosed with diseases expected to be concomitant to or indirect consequences of chronic headacheCitation39. This is especially true for a large number of mental disorder diagnosesCitation39,Citation40. Therefore, these comorbidity results suggest that the migraine patients receiving treatment with CGRP mAbs or BoNTA are chronically, severely affected patients. Interestingly, cohort 3 was generally older than cohort 1 and 2, while patients in cohort 3b were less so. Unfortunately, it is not possible to interpret these differences based on a claims data analysis. Younger patients may have not yet developed a need for preventive treatment due to their early stage of the disease. On the other hand, the patients in cohort 3b might be the younger patients with a high medical need who require preventive treatment and who act as early adopters of new available treatment options (CGRP mAb). It will be interesting to see the development of this patient group once the sample size increases in the coming years.

The mean number of all-cause outpatient provider visits (2018: 34.1 visits, 2019: 32.6 visits) was proportionally high in patients treated with CGRP mAbs. In comparison, the results of the BARMER Physician Report showed an average of 12.1 days for men and 16.8 days for women in terms of billing for all-cause healthcare services in 2019Citation41. Specifically in CGRP mAb-treated patients, 19.7 (in 2018) and 17.7 (in 2019) reported outpatient provider visits were migraine-related, and about 6 visits were reported by specialists (neurologists and pain specialists). These results may reflect the recommendations for patients treated with CGRP mAbs to be monitored by neurologists and pain specialists who are experienced in migraine diagnosis and treatmentCitation42–44. In addition, the frequency of reported physician visits may be related to the frequency of these patients obtaining prescriptions for their migraine treatment. These patients had an average of 4 to 12 prescriptions for acute treatments and 4 to 8 prescriptions for preventive treatments per year. Both of these types of prescriptions would have required a prescribing physician – thus contributing to the high number of observed outpatient provider visits. Furthermore, 36.6% (in 2018) and 40.0% (in 2019) of patients receiving CGRP mAbs took sick leave, which would have required a physician to issue a sick leave certificate – therefore adding to the reported number of physician visits. As indicated by this analysis and in line with findings from surveys conducted by Müller et al.Citation45 and Koch et al. Citation46, consultation behavior is significantly associated with headache frequency and migraine treatment involves a variety of healthcare providers. Finding appropriate treatment may often require multiple referrals to different specialists or headache centersCitation46. Hence, a high number of outpatient visits may be necessary, especially for severely affected patientsCitation45, until a migraine medication is properly matched to a patient”s specific needs.

In terms of hospitalizations, this analysis depicted a high proportion of patients receiving CGRP mAb treatment having all-cause (2018: 46.4%, 2019: 37.7%) and migraine-related hospitalizations (2018: 33.0%, 2019: 21.0%). Assuming patients starting therapy with CGRP mAbs are severely affected by migraine and therefore hospitalized more frequently, the results correspond to findings of the claims data study by Roessler et al.Citation11.

Among patients receiving CGRP mAb prophylaxis, a large proportion of 40% took all-cause sick leave for an average of 54 days (2018) and 42 days (2019) per year, and 25% took migraine-related sick leave for an average of 45 days (2018) and 34 days (2019) per year. These results are consistent with previous studies on sick leave in preventively treated migraine patientsCitation38 and in improved vs worsened/stable migraineCitation47, therefore, suggesting that a higher proportion and longer duration of sick leave might be related to migraine severity.

Overall, patients initiating treatment with CGRP mAbs were more likely to receive additional migraine-specific treatments, particularly triptans, and to have more records of migraine-related comorbidities, outpatient provider visits, hospitalizations, and sick leave. Additionally, an increased disease burden was observed for patients receiving BoNTA. As confirmed by other studies, HCRU is generally higher for patients with frequent and severe migraine attacks (represented by the group of CGRP mAb- and BoNTA-treated patients) than for patients with infrequent or less severe migraine attacksCitation11,Citation36,Citation38,Citation47. The results of this analysis indicated that more effective preventive treatments are needed to adequately treat migraines. CGRP mAbs may represent an improvement in the care of migraine patients, but further research with a longer follow-up would be needed to confirm whether CGRP mAbs are a sufficient solution for this difficult-to-treat population.

Limitations

In general, claims data is an appropriate and comprehensive tool for analyzing epidemiological measures, HCRU, and health care costs, as this data is recorded independently of any study purposes or recruitment for clinical research. Nevertheless, due to the nature of the underlying data, some limitations should be considered when interpreting the results.

This study describes the current care situation of differently preventive-treated migraine patients in the early stages of CGRP mAb availability in Germany and assesses corresponding disease burden from the perspective of the German SHI. A comparison of the disease burden of patients treated with different preventive treatment options was not intended.

The decision for a descriptive study design was based on the fact that only a short observation period of 2 years with CGRP mAb in the market was available at the time of study conduct. With only 14 months of follow-up after the approval of the first CGRP mAb, erenumab, in November 2018 in Germany, the number of CGRP mAb-treated patients is small, and comparisons between 2018 and 2019 may not be meaningful. Also, based on the study design a comparison between cohorts was not possible due to the differences in age and sex distribution as well as the fact that patients may also find themselves in different stages of their migraine journey. To account for the differences between the respective cohorts in future research, more recent data, a larger sample size, as well as a sufficient follow-up period will be required.

Due to the short study period, no valid data could be obtained on previous treatment pathways of CGRP mAb-treated patients, and thus on adherence to treatment guidelines. Equally, adherence and persistence of CGRP mAb treatment and related switching and discontinuation rates could not be validly assessed based on the short follow-up period available.

Furthermore, the use of the M2Q criterion in our analysis may be associated with an underestimation of the migraine prevalence. While considering only patients with ≥2 outpatient diagnosis records in two different quarters within one year increases diagnostic confidence, it excludes migraine patients with only one diagnosis during the analysis period. Also, patients with one diagnosis in the observation period and the second diagnosis at the end of the previous year or the beginning of the following year were excluded based on the M2Q criterion.

Only migraine patients with an ICD-10-GM diagnosis record for migraine could be included in this claims data analysis, hence excluding patients who may not have visited a physician for this purpose and underestimating the estimated rate of migraine in this analysis. Regarding the treatment of migraine, it should be considered that prescription claims do not include a specific indication for treatment. In both cohorts of patients classified as preventive-treated and off-label preventive-treated migraine patients, it may be possible that respective substances may have been prescribed on-label for another indication. However, because the patient selection was based on a primary and secondary inpatient as well as verified and validated (via M2Q criterion) outpatient ICD-10-GM diagnosis codes for migraine, it can be assumed that these preventive (off-label) treatments were intended to treat migraine in those patients. Additionally, the prescription data does not include OTC medications, as these are not reimbursed by the SHI. This may result in an underestimation of acute medication use, as common OTC medications (e.g. acetylsalicylic acid, ibuprofen, and paracetamol) may be frequently used for the acute treatment of migraines. Moreover, some triptans (naratriptan, almotriptan, and sumatriptan 50 mg) approved for migraine-specific acute treatment are also available as OTC in Germany. Since only triptan prescriptions covered by the SHI were captured in our analysis, the number of patients receiving triptans and the corresponding prescription frequency may have been underestimated. This might have also led to an underestimation of the prevalence of migraine as patients with mild and/or less frequent symptoms might not have seen a clinician during our observation period but have treated themselves with OTC triptans. Our results may therefore represent the more severely affected patients of the migraine spectrum.

As claims data only record sick leave where a physician issues a sick leave certificate, an underestimation of DOSL cannot be ruled out. Sick leave may have been further underreported because sick leave periods with less than 3 days could not be conclusively analyzed, as not all employment contracts require a sick leave note from the first day of illness in Germany.

In general, analysis of observational data allows an association between variables to be made but does not necessarily determine causality. It was not possible to draw conclusions on whether physician contacts or hospitalizations increased the chance of receiving preventive medication, or whether patients receiving a certain preventive treatment needed to see a physician more often or stay in the hospital longer due to more severe disease. Reasons for the observed higher disease burden of CGRP mAb- and BoNTA-treated patients could be multifactorial, and the purely descriptive analyses do not allow for assessment of causality when comparing treatment groups.

Conclusion

The results of this claim data study indicate a high disease burden of migraine in Germany, reflected by increased medication use, comorbidities, and HCRU. However, a high proportion of migraine patients identified in this analysis still received no preventive treatment or were treated only with off-label preventive medication. This analysis showed a high disease burden in terms of triptan prescriptions, comorbidities, and HCRU in patients treated with CGRP mAbs. Accordingly, the results suggest that patients treated preventively with CGRP mAbs, shortly after product launch in Germany, were severely affected chronic migraine patients. Based on a corresponding increased burden of disease, it can also be assumed that patients treated with BoNTA are among the most severely affected patients. These findings will need to be confirmed by further research assessing the impact of CGRP mAbs on HCRU compared to other migraine-specific treatment options once a longer follow-up period is available.

Transparency

Author contributions

C.G., K.S., A.H., T.M., A.E., and C.J. were responsible for conception, design and planning of the analysis. Data acquisition was performed by K.S. and C.J., and K.S., A.H., T.M., A.E., and C.J. were in charge of data analysis. The interpretation of the results was carried out by C.G., K.S., A.H., C.S., T.M., A.E., and C.J. Finally, C.G., K.S., A.H., C.S., T.M., A.E., B.F., and C.J. were responsible for critical review or revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (998.1 KB)Acknowledgements

The analyses were performed in collaboration with Wolfgang Greiner and the Institute for Applied Health Research Berlin (InGef). Medical writing support was provided by Hubert Kusdono, of Xcenda LLC. All services were funded by AbbVie.

Declaration of funding

AbbVie contributed to the design; analysis, and interpretation of data as well as in writing, reviewing, and approval of the final version. No honoraria or payments were made for authorship.

Declaration of interest of financial/other relationships

C.G. has received honoraria for consulting and lectures within the past three years from Allergan Pharma, Lilly, Novartis Pharma, Hormosan Pharma, Grünenthal, Sanofi-Aventis, Weber & Weber, Lundbeck, Perfood, and TEVA. His research is supported by a grant from the German Research Foundation (DFG). He does not hold any stocks of pharmaceutical companies. He is honorary secretary of the German Migraine and Headache Society. K.S. and C.J. are employed by Xcenda GmbH which received consulting fees for the execution of the analysis from AbbVie Deutschland GmbH & Co. KG. A.H., C.S., T.M., and B.F. are employees of AbbVie and may own AbbVie stock. A.E. was an employee of AbbVie at the time this analysis was planned and executed.

Data availability statement

A retrospective database analysis was conducted using anonymized claims from the “Institute for Applied Health Research Berlin” (InGef) Research Database. The data used in this analysis cannot be made available in the manuscript, the supplemental files, or in a public repository due to German data protection laws (Bundesdatenschutzgesetz). To facilitate the replication of results, anonymized data used for this analysis are stored on a secure drive at InGef. Access to the data used in this analysis can only be provided to external parties under the conditions of the cooperation contract of this research project and can be assessed upon request after written approval ([email protected]), if required.

Notes

i Pursuant to Annex VI, Section K of the German Medicinal Product DirectiveCitation48, valproic acid was approved as off-label medication for migraine prophylaxis in Germany until August 2020 and thus, was treated as on-label agent in this analysis.

References

- Diener H-C, Förderreuther S, Kropp P. Therapie der Migräneattacke und Prophylaxe der Migräne, S1-Leitlinie [Migraine attack therapy and migraine prophylaxis, S1 guideline]. Berlin: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Neurologie [German Society for Neurology]; 2022. Leitlinien für Diagnostik und Therapie in der Neurologie [Guidelines for diagnostics and therapy in neurology]; AWMF register number: 030/057. German. Available from: https://dgn.org/leitlinie/118.

- Steiner TJ, Stovner LJ, Jensen R, et al. Migraine remains second among the world”s causes of disability, and first among young women: findings from GBD2019. J Headache Pain. 2020;21(1):137.

- Amoozegar F, Khan Z, Oviedo-Ovando M, et al. The burden of illness of migraine in Canada: new insights on humanistic and economic cost. Can J Neurol Sci. 2022;49(2):249–262.

- Linde M, Gustavsson A, Stovner LJ, et al. The cost of headache disorders in Europe: the eurolight project. Eur J Neurol. 2012;19(5):703–711.

- Seddik AH, Branner JC, Ostwald DA, et al. The socioeconomic burden of migraine: an evaluation of productivity losses due to migraine headaches based on a population study in Germany. Cephalalgia. 2020;40(14):1551–1560.

- Shimizu T, Sakai F, Miyake H, et al. Disability, quality of life, productivity impairment and employer costs of migraine in the workplace. J Headache Pain. 2021;22(1):29.

- Tu S, Liew D, Ademi Z, et al. The health and productivity burden of migraines in Australia. Headache. 2020;60(10):2291–2303.

- Evers S, Afra J, Frese A, et al. EFNS guideline on the drug treatment of migraine: revised report of an EFNS task force. Eur J Neurol. 2009;16(9):968–981.

- Katsarava Z, Mania M, Lampl C, et al. Poor medical care for people with migraine in Europe – Evidence from the eurolight study. J Headache Pain. 2018;19(1):10.

- Piccinni C, Cevoli S, Ronconi G, et al. A real-world study on unmet medical needs in triptan-treated migraine: prevalence, preventive therapies and triptan use modification from a large italian population along two years. J Headache Pain. 2019;20(1):74.

- Roessler T, Zschocke J, Roehrig A, et al. Administrative prevalence and incidence, characteristics and prescription patterns of patients with migraine in Germany: a retrospective claims data analysis. J Headache Pain. 2020;21(1):85.

- World Health Organization. Atlas of headache disorders and resources in the world 2011. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44571/9789241564212_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- Ziegeler C, Brauns G, Jürgens TP, et al. Shortcomings and missed potentials in the management of migraine patients - Experiences from a specialized tertiary care center. J Headache Pain. 2019;20(1):86.

- Radtke A, Neuhauser H. Prevalence and burden of headache and migraine in Germany. Headache. 2009;49(1):79–89.

- Blumenfeld AM, Bloudek LM, Becker WJ, et al. Patterns of use and reasons for discontinuation of prophylactic medications for episodic migraine and chronic migraine: results from the second international burden of migraine study (IBMS-II). Headache. 2013;53(4):644–655.

- Hepp Z, Dodick DW, Varon SF, et al. Persistence and switching patterns of oral migraine prophylactic medications among patients with chronic migraine: a retrospective claims analysis. Cephalalgia. 2017;37(5):470–485.

- Hepp Z, Dodick DW, Varon SF, et al. Adherence to oral migraine-preventive medications among patients with chronic migraine. Cephalalgia. 2015;35(6):478–488.

- Allergan Inc. : BOTOX® von Allergan feiert 25 Jahre Zulassung in Deutschland [BOTOX® from Allergan celebrates 25 years of approval in Germany] Internet]2018. updated 2018 Dec 5; cited 2022 Mar 30]. German. Available from: https://www.allergan.de/de-de/news/news/botox-allergan-celebrates-25-years.aspx.

- AbbVie Ltd: BOTOX 100 Units: Summary of product characteristics [Internet]. Randalls Way, Leatherhead (UK): Datapharm Ltd; 2022. [updated 2022 May 23; cited 2023 Jan 20]. Available from: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/112.

- Aurora S, Dodick D, Turkel C, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA for treatment of chronic migraine: results from the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase of the PREEMPT 1 trial. Cephalalgia. 2010;30(7):793–803.

- Diener H-C, Dodick D, Aurora S, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA for treatment of chronic migraine: results from the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase of the PREEMPT 2 trial. Cephalalgia. 2010;30(7):804–814.

- Charles A, Pozo-Rosich P. Targeting calcitonin gene-related peptide: a new era in migraine therapy. Lancet. 2019;394(10210):1765–1774.

- Gemeinsamer Bundesausschuss [Federal Joint Committee]: Nutzenbewertungsverfahren zum Wirkstoff Erenumab (Migräne-Prophylaxe) [Benefit assessment procedure for the active substance erenumab (migraine prophylaxis)] [Internet]. 2018. updated 2019 May 2; cited 2023 Jan 20]. GermanAvailable from https://www.g-ba.de/bewertungsverfahren/nutzenbewertung/411/.

- Gemeinsamer Bundesausschuss [Federal Joint Committee]: Nutzenbewertungsverfahren zum Wirkstoff Galcanezumab (Migräne-Prophylaxe) [Benefit assessment procedure for the active substance galcanezumab (migraine prophylaxis)] [Internet]. 2019. updated 2019 Sept 19; cited 2023 Jan 20]. GermanAvailable from https://www.g-ba.de/bewertungsverfahren/nutzenbewertung/450/.

- Gemeinsamer Bundesausschuss [Federal Joint Committee]: Nutzenbewertungsverfahren zum Wirkstoff Fremanezumab (Migräne-Prophylaxe) [Benefit assessment procedure for the active substance fremanezumab (migraine prophylaxis)] [Internet]. 2019. updated 2019 Nov 7; cited 2023 Jan 20]. GermanAvailable from https://www.g-ba.de/bewertungsverfahren/nutzenbewertung/462/.

- European Medicines Agency (EMA): EPAR product information - Vyepti, eptinezumab Internet]2022. [updated 2022 Nov 29; cited 2023 Jan 20]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/vyepti-epar-product-information_en.pdf.

- Diener H-C, May A. Prophylaxe der Migräne mit monoklonalen Antikörpern gegen CGRP oder den CGRP-Rezeptor, Ergänzung der S1-Leitlinie [Prophylaxis of migraine with monoclonal antibodies to CGRP or the CGRP receptor, S1 guideline supplement.]. Berlin: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Neurologie [German Society for Neurology]; 2019. Leitlinien für die Therapie der Migräneattacke und Prophylaxe der Migräne [Guidelines for migraine attack therapy and migraine prophylaxis]; AWMF register number: Supplement to 030/057. German. Available from: https://dgn.org/leitlinie/154.

- Statistisches Bundesamt DESTATIS [Federal Office of Statistics]: Bevölkerung nach Nationalität und Geschlecht [Population by nationality and sex] [Internet]2021. [updated 2021 June 21; cited 2023 Jan 20]. German. Available from: https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Bevoelkerung/Bevoelkerungsstand/Tabellen/zensus-geschlecht-staatsangehoerigkeit-2020.html.

- Bundesministerium für Gesundheit : Kennzahlen der Gesetzlichen Krankenversicherung 2010 bis 2022 [Key figures for the statutory health insurance 2010 to 2022] [Internet]2022. [updated 2022 June; cited 2023 Jan 20]. German. Available from: https://www.bundesgesundheitsministerium.de/fileadmin/Dateien/3_Downloads/Statistiken/GKV/Kennzahlen_Daten/KF2022Bund_Juni_2022.pdf.

- Andersohn F, Walker J. Characteristics and external validity of the German health risk institute (HRI) database. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2016;25(1):106–109.

- Ludwig M, Enders D, Basedow F, et al. Sampling strategy, characteristics and representativeness of the InGef research database. Public Health. 2022;206:57–62.

- Bundesamt für Soziale Sicherung [Federal Office for Social Security]: Festlegungen nach § 8 Absatz 4 RSAV für das Ausgleichsjahr 2022. [Determinations pursuant to Section 8 (4) RSAV for the compensation year 2022] [Internet]. 2021 [updated 2021 Sep 30; cited 2023 Jan 20]. German. Available from: https://www.bundesamtsozialesicherung.de/fileadmin/redaktion/Risikostrukturausgleich/Festlegungen/2022/03_Klassifikation_AJ2022_Festlegung.zip.

- Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung (KBV) [National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians ]: Schlüsseltabellen S_BAR2_ARZTNRFACHGRUPPE (OID: 1.2.276.0.76.3.1.1.5.2.23) [Key tables S_BAR2_ARZTNRFACHGRUPPE (OID: 1.2.276.0.76.3.1.1.5.2.23)] [Internet]. 2019 [updated 2019 Apr 1; cited 2023 Jan 20]. German. Available from: https://applications.kbv.de/S_BAR2_ARZTNRFACHGRUPPE_V1.01.xhtml.

- Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung (KBV) [National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians]: Vereinbarung von Qualitätssicherungsmaßnahmen nach § 135 Abs. 2 SGB V zur schmerztherapeutischen Versorgung chronisch schmerzkranker Patienten [Agreement on quality assurance measures in accordance with Section 135 (2) of the German Social Code, Book V for pain therapy care for patients with chronic pain] [Internet]. 2004. [updated 2016 Oct 1; cited 2023 Jan 20]. German. Available from: https://kbv.de/media/sp/Schmerztherapie.pdf.

- Novartis Pharma GmbH. Dossier zur Nutzenbewertung gemäß § 35a SGB V zu Erenumab (Aimovig®) - Modul 3A [Dossier for the benefit assessment according to Section 35a SGB V on erenumab (Aimovig®) - Module 3A]. 2018. German. Available from: https://www.g-ba.de/downloads/92-975-2732/2018-10-22_Modul3A_Erenumab.pdf.

- Techniker Krankenkasse (TK). Kopfschmerzreport 2020 – Prävalenz, Pillen und Perspektiven [Headache Report 2020 - Prevalence, Pills and Perspectives]. Hamburg: Techniker Krankenkasse; 2020. Kopfschmerzreport [Headache Report]. German. Available from: https://www.tk.de/resource/blob/2088842/66767380cf7cce49b345b06baa704019/kopfschmerzreport-2020-data.pdf.

- Müller B, Dresler T, Gaul C, et al. More attacks and analgesic use in old age: self-reported headache across the lifespan in a German sample. Front Neurol. 2019;10:1000.

- Hardtstock F, Katsarava Z, Wilke T, et al. Real-world treatment and associated healthcare resource use among migraine patients in Germany. Ann Head Med. 2020;4:4.

- Grobe T, Steinmann S, Szecsenyi J. BARMER Arztreport 2017 [BARMER Physician Report 2017]. Berlin: Barmer Ersatzkasse; 2017. Schriftenreihe zur Gesundheitsanalyse [Series of publications on health analysis]; Volume 1. German. Available from: https://www.barmer.de/resource/blob/1026820/40985c83a99926e5c12eecae0a50e0ee/barmer-arztreport-2017-band-1-data.pdf.

- Porst M, Wengler A, Leddin J, et al. Migräne und Spannungskopfschmerz in Deutschland: Prävalenz und Erkrankungsschwere im Rahmen der Krankheitslast-Studie BURDEN 2020 [migraine and tension headache in Germany: prevalence and disease severity in the BURDEN 2020 disease burden study]. J Health Monit. 2020;5(S6):1–26. German.

- Grobe T, Szecsenyi J. BARMER Arztreport 2021 [BARMER Physician Report 2021]. Berlin: Barmer Ersatzkasse; 2021. Schriftenreihe zur Gesundheitsanalyse [Series of publications on health analysis]; Volume 27. German. Available from: https://www.barmer.de/resource/blob/1027518/043d9a7bf773a8810548d18dec661895/barmer-arztreport-2021-band-27-bifg-data.pdf.

- European Medicines Agency (EMA): EPAR product information - Aimovig, erenumab Internet]2018. [updated 2022 Mar 1; cited 2023 Jan 20]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/aimovig-epar-product-information_en.pdf.

- European Medicines Agency (EMA): EPAR product information - Ajovy, fremanezumab Internet]2019. updated 2022 June 7; cited 2023 Jan 20]. Available from https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/ajovy-epar-product-information_en.pdf.

- European Medicines Agency (EMA): EPAR product information - Emgality, galcanezumab Internet]2019. updated 2022 Nov 11; cited 2023 Jan 20]. Available from https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/emgality-epar-product-information_en.pdf.

- Müller B, Dresler T, Gaul C, et al. Use of outpatient medical care by headache patients in Germany: a population-based cross-sectional study. J Headache Pain. 2020;21(1):49.

- Koch M, Katsarava Z, Baufeld C, et al. Migraine patients in Germany – Need for medical recognition and new preventive treatments: results from the PANORAMA survey. J Headache Pain. 2021;22(1):106.

- Vo P, Swallow E, Wu E, et al. Real-world migraine-related healthcare resource utilization and costs associated with improved vs. worsened/stable migraine: a panel-based chart review in France, Germany, Italy, and Spain. J Med Econ. 2021;24(1):900–907.

- Gemeinsamer Bundesausschuss [Federal Joint Committee]: Beschluss zur Arzneimittel-Richtlinie/Anlage VI: Off-Label-Use, Aktualisierung Teil A Ziffer V, Valproinsäure bei der Migräneprophylaxe im Erwachsenenalter [Decision on the Guideline on Medicinal Products/Annex VI: Off-Label Use, Update Part A Item V, Valproic Acid in the Prophylaxis of Migraine in Adults] [Internet]. 2020. [updated 2020 Aug 1; cited 2023 Jan 20]. German. Available from: https://www.g-ba.de/beschluesse/4212/.