Abstract

Aims

To describe real-world esketamine nasal spray access and use as well as healthcare resource use (HRU) and costs among adults with evidence of major depressive disorder (MDD) with suicidal ideation or behavior (MDSI).

Methods

Adults with ≥1 claim for esketamine nasal spray and evidence of MDSI 12 months before/on the date of esketamine initiation (index date) were selected from Clarivate’s Real World Data product (01/2016–03/2021). Patients initiated esketamine on/after 03/05/2019 (esketamine approval for treatment-resistant depression; later approved for MDSI on 08/05/2020) were included in the overall cohort. Esketamine access (measured as approved/abandoned/rejected claims) and use were described post-index; HRU and healthcare costs (2021 USD) were described over 6 months pre- and post-index.

Results

Among 269 patients in the overall cohort with esketamine pharmacy claims, 46.8% had the first pharmacy claim approved, 38.7% had it rejected, and 14.5% abandoned their claim; 169 patients were initiated on esketamine in the overall cohort (mean age 40.9 years, 62.1% female); 45.0% had ≥8 esketamine treatment sessions (recommended per label) with a mean [median] of 85.0 [58.5] days from index to 8th session (per label 28 days). Among 115 patients with ≥6 months of data post-index, in the 6-month pre- and post-index, respectively, 37.4 and 19.1% had all-cause inpatient admissions, 42.6 and 33.9% had emergency department visits, 92.2 and 81.7% had outpatient visits; mean ± standard deviation all-cause monthly total healthcare costs were $8,371±$15,792 and $6,486±$7,614, respectively.

Limitations

This was a descriptive claims-based analysis; no formal statistical comparisons were performed due to limited sample size as data covered up to 24 months of esketamine use in the US clinical setting.

Conclusions

Nearly half of patients experience access issues with first esketamine nasal spray treatment session. All-cause HRU and healthcare costs trend lower in the 6 months after relative to 6 months before esketamine initiation.

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY

Major depressive disorder (MDD), or clinical depression, can sometimes be accompanied by preoccupation with suicide along with suicidal behavior. Patients diagnosed with MDD with suicidal ideation or behavior (MDSI) can vary in their reactions to this condition, and some never seek treatment. This study investigated treatment patterns in real-world clinics of a recently approved nasal spray therapy, esketamine, which helps improve depressive symptoms in patients with MDSI. The study results highlight challenges related to esketamine treatment access, particularly for the first treatment session. Still, healthcare resource utilization and healthcare costs trended lower following treatment initiation with esketamine in MDSI, suggesting the potential benefits of esketamine in mitigating the clinical and economic burden of MDSI among those who gain access to the drug. Streamlining the approval process by health plan providers to remove hindrances related to compliance with plan requirements may ensure more timely access to esketamine for MDSI.

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a recurrent psychiatric condition affecting 8.4% of adults in the United States (US) Citation1. MDD causes considerable impairments in multiple areas of functioning that negatively affect patients’ livesCitation2. Suicidal ideation and behavior can potentially be a devastating symptom of MDDCitation3. Patients with MDD are at increased risk for suicideCitation4,Citation5, particularly during major depressive episodes (MDEs)Citation6. According to the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, nearly 50% of adult patients with an MDE in the past year had either serious suicidal ideations or made suicide plans or attemptsCitation7.

Notably, the prevalence of MDD with acute suicidal ideation or behavior (MDSI) is likely underestimated given MDSI is an underdiagnosed condition. Some individuals with MDSI never seek mental health treatment, and hence are never diagnosed, for reasons such as stigma, concerns about being committed to a psychiatric hospital, and lack of insurance coverageCitation1,Citation8,Citation9. The prevalence of MDSI may have further increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, as quarantine measures and financial losses have placed a substantial strain on the mental health of the general population, leaving individuals vulnerable to mental health issues and suicidal behaviorCitation10,Citation11. For patients with existing MDSI, depressive symptoms may worsen, further contributing to increased suicidal riskCitation12.

MDSI has been shown to be associated with a substantial economic burdenCitation13,Citation14. A recent US studyCitation13 reported that among commercially insured adults with MDSI, the incremental healthcare costs relative to the non-MDD cohort were $7,839 per patient within the first month of a suicide-related event, largely driven by acute hospital care following the event. That study also found that nearly half of patients with MDSI did not receive antidepressants or psychotherapy prior to the suicide-related event. These findings suggest that early identification and treatment of patients with MDSI may reduce the risk of suicidal ideation or behavior, which may in turn prevent the subsequent economic burden associated with acute care.

Antidepressants, as monotherapy or combination therapy, have demonstrated efficacy in treating depressive episodes, which supports their use for individuals with MDSICitation4. For patients with MDD at high risk of suicide, electroconvulsive therapy may be consideredCitation3. Esketamine nasal spray is a novel therapy approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment-resistant depression (TRD) on 03/05/2019Citation15,Citation16 and for MDSI on 08/05/2020Citation17. The esketamine MDSI trials were among the first antidepressant global registration studies to enroll patients with MDD at imminent risk of suicide, in which esketamine has demonstrated rapid and significant reduction in depressive symptoms amongst patients with MDSI, when taken in combination with an oral antidepressantCitation18,Citation19. Since suicidal ideation or behavior symptoms may manifest in both MDD and TRDCitation4, patients with MDSI could have been initiated on esketamine after its approval for either indication. Consequently, variations in patient profiles related to drug indication approvals may exist in clinical practice.

Our previous study using the IBM MarketScan Commercial and Medicare Supplemental Databases has found that most patients with TRD who initiated esketamine nasal spray completed induction treatment at dosing intervals longer than the label recommendationCitation20. However, little is known about esketamine use for MDSI in the real world. Notably, TRD and MDSI are two distinct indications for esketamine nasal spray, and that timely access to treatment can be particularly important for patients with MDSI. Therefore, based on just over six months of data available since the approval of esketamine nasal spray for MDSI and up to 24 months since its approval for TRD at the time of the study initiation, the aim of this hypothesis generating study was to understand characteristics of patients with MDSI initiated on esketamine nasal spray and describe their treatment patterns, healthcare resource use (HRU), costs, as well as access to esketamine nasal spray. This new study used Clarivate’s Real World Data (RWD) product, an open claims database containing information on prescription life cycle allowing for an analysis of access to esketamine based on approved, rejected, and abandoned esketamine pharmacy claims and reasons for claim rejection by insurer.

Methods

Data source

Data were obtained from the Clarivate’s RWD product (01/2016–03/2021), a provider-based open claims database that collects and links information from different pharmacy and clinical networks. The RWD product contains patient demographics, medical claims (including charged amounts, i.e. payment amount for the entire claim as requested by providers), and pharmacy claims (including costs from a private payer’s perspective, as well as status of pharmacy claims, i.e. approved, rejected, abandoned [defined below]). The RWD product includes patients from all US regions. Data were de-identified and complied with the patient requirements of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996; therefore, no review by an institutional review board was required per Title 45 of CFR, Part 46.101(b)(4)Citation21.

Study design

A retrospective observational descriptive study design was used. The index date was defined as the date of initiation of esketamine nasal spray on or after the date of evidence of MDSI, and on or after 03/05/2019 (the date of esketamine nasal spray approval for TRD, its first indication, was used to preserve sample size). The baseline period was defined as the 12-month period of continuous clinical activity before the index date. Clinical activity was based on the first and last patient-level activity flags in the data, with flags defined as either a pharmacy or a medical claim. The follow-up period spanned from the index date until the earliest of the end of continuous clinical activity or end of data availability.

Study cohort and subgroups

To increase sample size, patients with MDSI initiated on esketamine on or after 03/05/2019 (esketamine approval date for TRD in the US) were included in the overall cohort. Given the esketamine approval date for MDSI in the US was on 08/05/2020, a subgroup analysis among patients with MDSI initiating esketamine only on or after 08/05/2020 (i.e. the 2020-initiator subgroup) was also conducted to validate trends observed in the overall cohort.

Among patients in the overall cohort, patients with ≥6 months of clinical activity following the index date comprised another subgroup (i.e. the 6-month subgroup), in which outcomes were described during the most recent 6 months of the baseline period and during the first 6 months of the follow-up period.

Since the recommended treatment course of esketamine for MDSI is 8 treatment sessions in 1 monthCitation17, a sensitivity analysis was also conducted among patients in the overall cohort who had ≥1 month of clinical activity following the index date (i.e. the 1-month subgroup); in this analysis, outcomes were described during the last month of the baseline and the first month of the follow-up periods.

Sample selection

Patients were included in the study if they met the following criteria: had ≥1 pharmacy claim (National Drug Codes [NDC] codes: 50458-0028-00, 50458-0028-02, 50458-0028-03) or medical claim for esketamine nasal spray (Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System [HCPCS] codes: G2082, G2083, S0013; International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Procedure Coding System: XW097M5) with the first claim on or after 03/05/2019; had evidence of MDSI during the baseline period or on the index date, defined as ≥1 claim with a code for either suicidal ideation (International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-10-CM]: R45.851) or behavior (suicide attempt or intentional self-harm as described by Hedegaard et al.Citation22) and ≥1 claim with a diagnosis for MDD (ICD-10-CM: F32.X [excluding F32.8 and F32.A], F33.X [excluding F33.8]); had ≥12 months of continuous clinical activity before the index date; and were ≥18 years old on the index date.

Patients were excluded from the study if they initiated esketamine before evidence of MDSI, before the approval date of esketamine for TRD (03/05/2019), and/or had ≥1 claim with a diagnosis for schizophrenia spectrum or other psychotic disorders during the baseline period (ICD-10-CM: F06.0, F06.1, F06.2, F20.81, F20.9, F21, F22, F23, F25.0, F25.1, F28, F29).

Outcome measures

Esketamine nasal spray access and use were reported for the overall cohort and the 2020-initiator subgroup. Specifically, access to esketamine was assessed among patients with pharmacy claims for esketamine of any status (i.e. approved, rejected, or abandoned), as claim status information was available only for pharmacy claims. Approved claims are claims submitted by a pharmacy and approved for payment by health plans after claims adjudication. Rejected claims are adjudicated claims for prescriptions denied by health plans. Abandoned claims are adjudicated claims for prescriptions, approved by health plans that patients decided to abandon, usually due to cost or non-compliance. Only the final status of each claim was reported. For esketamine use, esketamine treatment sessions (number, frequency, and dose) were assessed among patients with approved pharmacy or medical claims for esketamine. Esketamine treatment sessions were identified based on claims observed on unique days. The dose of esketamine treatment sessions was based on NDC and HCPCS codes for esketamine pharmacy and medical claims (i.e. the dose of 56 mg was identified using NDC code 50458-0028-02 and HCPCS code G2082, and the dose of 84 mg was identified using NDC code 50458-0028-03 and HCPCS code G2083; dose for HCPCS code S0013 was dependent on number of units).

The following outcomes were reported among the 6-month subgroup of the overall cohort during the 6 months pre- and post-index: severity of depressive symptoms based on the most recent diagnosis for MDD among patients with ≥1 MDD diagnosis both pre- and post-index (ICD-10-CM codes for severe: F32.2, F32.3, F33.2, F33.3; moderate: F32.1, F33.1; mild: F32.0, F33.0; unspecified: F32.9, F33.9; in remission: F32.4, F32.5, F33.4), all-cause and mental health–related per-patient-per-month (PPPM) HRU and healthcare costs. All-cause and mental health–related PPPM HRU and healthcare costs were also reported for the sensitivity analysis, in the 1-month subgroup during the 1 month pre- and post-index. Healthcare costs, which included pharmacy costs from a private payer’s perspective and medical costs reported as charged amounts were adjusted for inflation using the medical care component of the US Consumer Price Index and presented in 2021 US dollars.

Statistical analysis

Analysis was descriptive with means, standard deviations (SDs), and medians reported for continuous variables and frequencies and proportions reported for binary variables.

Results

Access to esketamine nasal spray

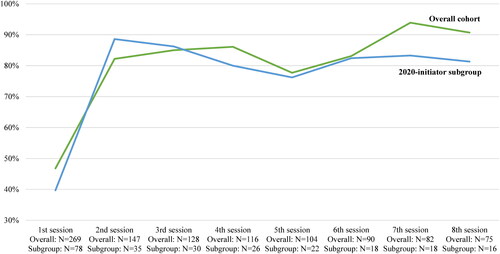

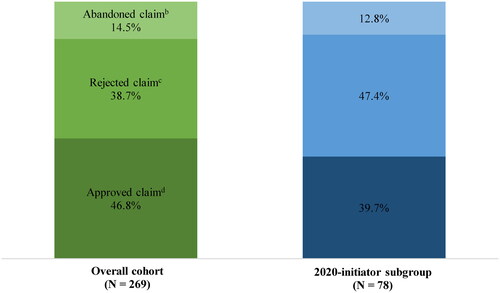

A total of 269 patients in the overall cohort and 78 patients in the 2020-initiator subgroup had pharmacy claims of esketamine nasal spray. When the claim for the first treatment session was a pharmacy claim, 46.8 and 39.7% of patients had the claim approved, 38.7 and 47.4% had the claim rejected, and 14.5 and 12.8% abandoned their claim, in the overall cohort and 2020-initiator subgroup, respectively (). The main reasons for rejections were “claim errors” (overall cohort: 52.9%; 2020-initiator subgroup: 54.1%), “not covered by plan” (overall cohort: 52.9%; 2020-initiator subgroup: 45.9%), and “prior authorization required” (overall cohort: 26.9%; 2020-initiator subgroup: 37.8%).

Figure 1. Proportion of patients with approved, rejected, and abandoned first esketamine nasal spray claimsa. Notes: (a) Assessed among patients for whom the first claim was a pharmacy claim. (b) Abandoned claims are adjudicated prescriptions (i.e. approved by health plans that patients decided to abandon, usually due to cost or non-compliance). (c) Rejected claims are adjudicated prescriptions denied by health plan and never received by patients. (d) Approved claims are adjudicated prescriptions submitted via pharmacy that are approved for payment by health plans.

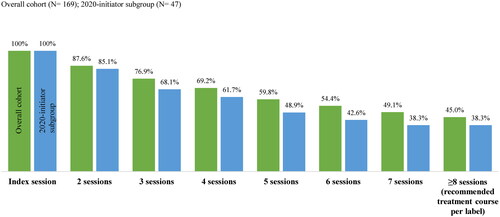

The approval rate of esketamine nasal spray treatment sessions was lowest for the first session and increased to 90.7 and 81.3% by the 8th session in the overall cohort and 2020-initiator subgroup, respectively (). The mean [median] number of attempts to submit a claim before receiving a final decision from health plans was 4.8 [3.0] and 4.0 [3.0] for the first esketamine treatment session and decreased to 2.0 [1.0] and 1.5 [1.0] attempts by the 8th session, in the overall cohort and 2020-initiator subgroup, respectively. The mean [median] time between the first attempt to submit the claim and the final decision was 7.9 [0.0] and 8.7 [0.0] days for the first esketamine treatment session and decreased to 0.4 [0.0] and 0.3 [0.0] days by the 8th session in the overall cohort and 2020-initiator subgroup, respectively.

Baseline characteristics among patients who received access to esketamine nasal spray

A total of 169 patients in the overall cohort and 47 in the 2020-initiator subgroup were initiated on esketamine nasal spray (i.e. had ≥1 approved pharmacy claim or a medical claim for esketamine).

Overall, patients had similar baseline characteristics (). Patients in the 2020-initiator subgroup were slightly younger than patients in the overall cohort (mean age of 37.7 vs. 40.9 years). Nearly all patients had a diagnosis of suicidal ideation or behavior during the baseline period (99.4% of the overall cohort and 97.9% of the 2020-initiator subgroup), with the remaining patients having their diagnosis on the index date. The mean [median] number of days from the most recent claim with a code for suicidal ideation or behavior during the baseline period (including the index date) to the index date was 134.1 [109.0] in the overall cohort and 117.9 [72.0] in the 2020-initiator subgroup. The most common sites of care of the most recent claim with a suicidal ideation or behavior code were inpatient (40.8% of the overall cohort and 44.7% of the 2020-initiator subgroup) and outpatient (37.3% of the overall cohort and 36.2% of the 2020-initiator subgroup).

Table 1. Patient baseline characteristics.

Furthermore, 12.4% of the overall cohort and 8.5% of the 2020-initiator subgroup had claims-based evidence of TRD (i.e. initiation of a new antidepressant therapy line of adequate dose after changing two different lines of adequate dose and duration within the MDE in which esketamine was initiated) at any time before or on the index date.

The mean [median] number of months of follow-up was 10.3 [9.8] in the overall cohort and 3.2 [3.6] in the 2020-initiator subgroup.

Pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapy use during follow-up period

In the overall cohort and 2020-initiator subgroup, respectively, 39.6% and 36.2% of patients had claims for ≥1 unique antidepressant agent during the follow-up period; the most frequently observed antidepressants are presented in . Also, 37.9% of the overall cohort and 27.7% of the 2020-initiator subgroup had a psychotherapy visit; and 16.6% in the overall cohort and 8.5% in the 2020-initiator subgroup received a psychiatric diagnostic evaluation. The proportion of patients who received care in an inpatient psychiatric facility during the follow-up period was 7.7% in the overall cohort and 2.1% in the 2020-initiator subgroup. The proportion of patients who received electroconvulsive therapy during the follow-up period was 5.9% in the overall cohort and 2.1% in the 2020-initiator subgroup.

Table 2. Antidepressant use during the follow-up period.

Number of esketamine nasal spray treatment sessions

During the follow-up period, patients in the overall cohort had a mean [median] of 11.1 [6.0] esketamine nasal spray treatment sessions, while patients in the 2020-initiator subgroup had a mean [median] of 7.9 [4.0] sessions. The proportion of patients completing ≥8 esketamine treatment sessions (recommended treatment course per label)Citation17 was 45.0% in the overall cohort and 38.3% in the 2020-initiator subgroup (). The mean [median] time from the index date to the 8th session was 85.0 [58.5] days in the overall cohort and 50.8 [49.0] days in the 2020-initiator subgroup; per label, esketamine is indicated as 8 doses in 4 weeks (28 days) for patients with MDSICitation17.

Most patients initiated esketamine with a dose of 56 mg (overall cohort: 74.6%; 2020-initiator subgroup: 61.7%) and titrated to the dose of 84 mg by the 2nd session (overall cohort: 58.8%; 2020-initiator subgroup: 70.0%); per label, the recommended dose of esketamine for MDSI is 84 mg and may be reduced to 56 mg based on tolerabilityCitation17.

Severity of depressive symptoms, HRU, and healthcare costs in the 6-month subgroup

Among 169 patients initiated on esketamine nasal spray, 115 (68.0%) had ≥6 months of follow-up after the index date. The mean [median] age of this 6-month subgroup was 42.0 [42.5] years and 65.2% were female.

Severity of depressive symptoms in the 6-month pre- and post-index periods

A total of 67.8% of patient in the 6-month subgroup had ≥1 diagnosis for MDD during both the 6-month pre- and post-index periods. The proportion of patients with severe MDD was 76.9% in the 6 months pre-index and 60.3% in the 6 months post-index (Supplementary Figure 1).

All-cause and mental health–related HRU in the 6-month pre- and post-index periods

All-cause and mental health–related HRU in the 6-month subgroup appeared lower in the 6 months after relative to the 6 months before esketamine initiation. During the 6-month pre- and post-index periods, 37.4 and 19.1% of patients had ≥1 all-cause inpatient admission, 42.6 and 33.9% had ≥1 all-cause emergency department visit, and 92.2 and 81.7% had ≥1 all-cause outpatient visit, respectively. Similar trends were observed for all mental health–related HRU components (Supplementary Figure 2).

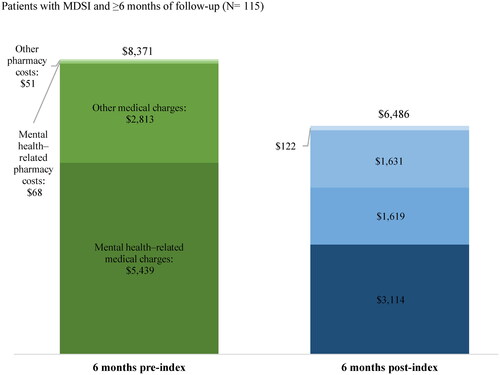

All-cause and mental health–related healthcare costs in the 6-month pre- and post-index periods

The total mean ± SD [median] all-cause PPPM healthcare costs (i.e. medical charges and pharmacy costs) incurred by patients in the 6-month subgroup were $8,371 ± $15,792 [$3,475] in the 6 months pre-index and $6,486 ± $7,614 [$3,906] in the 6 months post-index (). Specifically, the mean ± SD [median] all-cause PPPM medical healthcare charges were $8,252 ± $15,770 [$3,188] in the 6 months pre-index and $4,733 ± $7,505 [$1,652] in the 6 months post-index, driven by outpatient (mean ± SD [median]; pre-index: $4,439 ± $11,786 [$1,313], post-index: $2,570 ± $4,610 [$1,006]) and inpatient charges (mean ± SD [median]; pre-index: $2,507 ± $5,655 [$0], post-index: $1,188 ± $4,096 [$0]) (Supplementary Table 1). The proportion of mental health–related medical healthcare charges among all-cause medical healthcare charges were 65.9% in the 6 months pre-index and 65.8% in the 6 months post-index.

Figure 4. All-cause and mental health–related healthcare costs 6 months pre- and post-indexa–c. Notes: (a) Healthcare costs are reported per-patient-per-month and are adjusted for inflation using the 2021 US Consumer Price Index. (b) Medical charges are reported as the payment amount for the entire claim as requested by the provider; pharmacy costs are reported from a private payer’s perspective. (c) Mental health–related medical charges were identified based on claims with an ICD-10-CM diagnosis between F01 and F99 (inclusive). Abbreviations: ICD-10-CM, International Classification of Disease, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification; MDSI, major depressive disorder with acute suicidal ideation or behavior; US: United States.

Sensitivity analysis: HRU and healthcare costs in the 1-month subgroup

Among 169 patients initiated on esketamine nasal spray, 155 (91.7%) patients had ≥1 month of follow-up after the index date and were included in the sensitivity analysis.

All-cause and mental health–related HRU in the 1-month pre- and post-index periods

All-cause inpatient and outpatient HRU appeared to be lower in the month after esketamine initiation relative to the month before initiation. Specifically, 11.0 and 3.2% of patients had ≥1 all-cause inpatient admission, and 62.6 and 58.1% of patients had ≥1 all-cause outpatient visit during the 1-month pre- and post-index periods, respectively. Moreover, reductions in all mental health–related HRU components were observed (Supplementary Figure 3).

All-cause and mental health–related healthcare costs in the 1-month pre- and post-index periods

The total mean ± SD [median] all-cause PPPM healthcare costs incurred by patients in the 1-month subgroup were $6,941 ± $15,346 [$918] in the month pre-index and $8,546 ± $10,622 [$6,499] in the month post-index (Supplementary Figure 4). The mean ± SD [median] all-cause PPPM medical healthcare charges decreased from $6,786 ± $15,330 [$748] in the month pre-index to $5,007 ± $10,754 [$1,750] in the month post-index, driven by inpatient charges (Supplementary Table 2). The proportion of mental health–related medical healthcare charges among all-cause medical healthcare charges were 79.4% in the month pre-index and 59.6% in the month post-index.

Discussion

This real-world observational study highlights that patients with MDSI face challenges when accessing prescribed esketamine nasal spray in the real world, particularly for the first treatment session. At the same time, it suggests potential benefits of esketamine nasal spray in mitigating the clinical and economic burden of MDSI among those who manage to gain access to the drug.

Barriers to esketamine adoption in clinical practice, such as administrative requirements of prior authorization from payers, have been recognizedCitation23–25; however, studies specifically evaluating patient access to prescribed esketamine treatment are limited. The current claims-based analysis revealed that a large portion of patients with MDSI had difficulty accessing their initial esketamine treatment due to physician claim errors, treatment not covered by patient’s insurance, and prior authorization requirementCitation26. Patients may also be reluctant to be treated in hospitals due to stigma, but some insurance companies may require an inpatient admission prior to initiation of esketamine treatment. Notably, timely access to treatment is crucial for patients with MDSI because of the serious consequences if the condition is left untreated, as the functional and social impairments associated with the suicidal ideation or behavior of patients with MDSI can pose a negative impact on patients’ daily livingCitation14,Citation27.

In this study, among those who had access to the esketamine nasal spray, less than half completed the label-recommended treatment course, and the median time to completing the treatment was longer than the label recommendation. This may be due to the organizational challenges patients and their caregivers face complying with the treatment schedule. Esketamine is indicated for MDSI twice a week for four weeks, needs to be administered in a Risk Evaluation Management Strategy (REMS)–certified treatment center, and patients cannot drive after a treatment sessionCitation17. For working-age adults and their caregivers, a twice-a-week commute to a treatment center during the working hours with two additional hours of monitoring after each session could be burdensome. Of note, more than 95% of patients in this study were at the working age of under 65 years old. While the REMS requirements are intended to ensure the safe use of medicationsCitation28, support programs are warranted to help patients and caregivers manage the time and logistics related to the treatment.

Esketamine nasal spray was approved by the FDA for the treatment of MDSI in August 2020, and clinical trials of esketamine have demonstrated rapid reduction in depressive symptoms in patients with MDSI receiving esketamine and concomitant oral antidepressant, compared with those receiving placebo plus oral antidepressantCitation18,Citation19. However, MDSI has been associated with high HRU and healthcare costsCitation13,Citation14,Citation29, likely attributable to care in a hospital settingCitation3. In this study patient’s mean age and sex ratio were comparable to those in the esketamine MDSI trialsCitation18,Citation30,Citation31; a numerical decrease was observed in inpatient and emergency department visits and total healthcare costs 6 months following esketamine initiation, signaling a potential reduction in disease severity after treatment. The relatively higher healthcare costs in the 6 months pre-esketamine initiation could be due to the occurrence of suicidal ideation or behavior events, which often result in hospitalizations and could be costly. The currently observed reductions in HRU and costs were consistent with the apparent reduction in MDD severity post-esketamine based on diagnosis codes. While lower HRU, costs and MDD severity could be associated with esketamine initiation, it is important to note that these changes in the post-esketamine period may be subject to regression towards the mean, as patients with a suicidal ideation or behavior event at baseline may have spontaneous remission from this extreme symptom. Nonetheless, the presence and severity of depressive symptomsCitation32, as well as the time spent depressedCitation6, have been shown to increase suicidal risk in patients with MDD, highlighting that early access to effective treatment may not only prevent symptom escalation but also reduce the associated economic burden among patients with MDSI. As rapid access to effective treatment for the underlying depression, such as esketamineCitation17, is crucial in MDSI careCitation14,Citation27, health plan providers should ensure that timely access to esketamine is not hindered by compliance issues with plan requirements. Strategies to help patients with MDSI reach timely and effective care may prevent the devastating consequences of delayed treatment in this vulnerable population.

Esketamine nasal spray is indicated in conjunction with an oral antidepressant. The American Psychiatric Association guideline also recommends long-term use of antidepressants for suicidal patients with recurrent depressive disorder and highlights the central role of psychotherapies in the clinical care of suicidal patientsCitation4. In the current study, about 40% of patients with MDSI in the overall cohort had observed claims for antidepressants during the follow-up period and about one-third of patients were observed to receive psychotherapy. This lower than anticipated utilization of antidepressants and psychotherapies may be at least partially explained by the limitations of the data, as drug samples and drugs and medical services paid out-of-pocket or received from providers outside of the Clarivate’s RWD product network are not being captured. For the same reasons, the proportion of patients with TRD identified with a claims-based algorithm may be underreported.

Limitations

The findings of this study should be considered in light of certain additional limitations. First, pharmacy claims do not guarantee that the medication dispensed was taken as prescribed; with respect to esketamine pharmacy claims, the exact date of the esketamine administration may be unknown. Second, the results may not be generalizable to individuals without health insurance. Third, the requirement for patients to have ≥1 and ≥6 months of continuous clinical activity post-index may have introduced immortal-time bias. Fourth, at the time this analysis was conducted, the data covered only 24 months of esketamine use in the US clinical setting. While HRU and costs were compared during 6-month baseline and follow-up periods to preserve sample size, studies with more recent data and longer follow-up are needed to confirm the trends in this descriptive analysis and test hypotheses related to outcomes of esketamine use. Fifth, in pre/post analyses, time-varying events may influence the association of treatment initiation with observed outcomes. Lastly, since the study period covers the COVID-19 era, it is not possible to separate the impact on treatment patterns, HRU, and costs caused by this pandemic from those associated with esketamine treatmentCitation1,Citation11.

Conclusions

Patients with MDSI experience difficulties with access to prescribed esketamine nasal spray treatment. Efforts should be made to facilitate the coverage of esketamine nasal spray by health plan providers. The data also suggest that HRU and healthcare costs, as well as MDD severity based on diagnosis codes, trend lower after patients with MDSI initiate treatment with esketamine nasal spray. Future research should evaluate the effect of MDSI treatment with esketamine nasal spray on HRU and costs.

Transparency

Author contributions

MZ, DP, AS, and GCL contributed to study conception and design, collection and assembly of data, and data analysis and interpretation. AT and KJ contributed to study conception and design, data analysis and interpretation. All authors reviewed and approved the final content of this manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Medical writing support was provided by Flora Chik and Chris Crotty, employees of Analysis Group, Inc. Ella Daly contributed to the study design and interpretation of results and was an employee of Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC at the time this study was conducted.

Reviewer disclosures

A reviewer on this manuscript has received manuscript or speaker’s fees from Astellas, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Elsevier Japan, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Kyowa Yakuhin, Lundbeck Japan, Meiji Seika Pharma, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, MSD, Nihon Medi-Physics, Novartis, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Shionogi, Shire, Sumitomo Pharma, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Tsumura, Viatris, Wiley Japan, and Yoshitomi Yakuhin, and research grants from Eisai, Mochida Pharmaceutical, Meiji Seika Pharma, Shionogi and Sumitomo Pharma. The other peer reviewers on this manuscript have no other relevant financial relationships or otherwise to disclose.

Previous presentations

Part of the material in this manuscript has been presented at the American Psychiatric Association (APA) Annual Meeting in New Orleans, LA, May 21–25, 2022, the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology (ASCP) Annual Meeting in Scottsdale, AZ, May 31–June 3, 2022, and the Neuroscience Education Institute (NEI) 2022 Congress in Colorado Springs, CO, November 3–6, 2022.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (94.8 KB)Declaration statement of funding

This study was funded by Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC. The sponsor commissioned the study but had no role in the decision to publish the final paper.

Declaration statement of financial/other interests

AT and KJ are employees of Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, and are stockholders of Johnson & Johnson. MZ, DP, AS, and GCL are employees of Analysis Group, Inc., a consulting company that has provided paid consulting services to Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, which funded the development and conduct of this study and manuscript.

References

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: results from the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP21-07-01-003, NSDUH Series H-56). Rockville, MD. [updated 2021 Oct]. Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt35325/NSDUHFFRPDFWHTMLFiles2020/2020NSDUHFFR1PDFW102121.pdf.

- Otte C, Gold SM, Penninx BW, et al. Major depressive disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16065.

- Gelenberg A, Freeman M, Markowitz J. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:1–118.

- Jacobs DG, Baldessarini RJ, Conwell Y, et al. Assessment and treatment of patients with suicidal behaviors. APA Practice Guidelines. 2010;1:183.

- Cai H, Xie XM, Zhang Q, et al. Prevalence of suicidality in major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:690130.

- Holma KM, Melartin TK, Haukka J, et al. Incidence and predictors of suicide attempts in DSM-IV major depressive disorder: a five-year prospective study. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(7):801–808.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health – Appendix B: List of tables Rockville, MD2020 [cited 2022 March 30]. Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt35323/NSDUHDetailedTabs2020/NSDUHDetailedTabs2020/NSDUHDetTabsAppB2020.htm.

- Sheehan L, Dubke R, Corrigan PW. The specificity of public stigma: a comparison of suicide and depression-related stigma. Psychiatry Res. 2017;256:40–45.

- Yakunina ES, Rogers JR, Waehler CA, et al. College students’ intentions to seek help for suicidal ideation: accounting for the help-negation effect. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2010;40(5):438–450.

- Gunnell D, Appleby L, Arensman E, et al. Suicide risk and prevention during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(6):468–471.

- Ornell F, Schuch JB, Sordi AO, et al. Pandemic fear" and COVID-19: mental health burden and strategies. Braz J Psychiatry. 2020;42(3):232–235.

- Hao F, Tan W, Jiang L, et al. Do psychiatric patients experience more psychiatric symptoms during COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown? A case-control study with service and research implications for immunopsychiatry. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:100–106.

- Pilon D, Neslusan C, Zhdanava M[, et al. In press] economic burden of commercially insured patients with major depressive disorder and acute suicidal ideation or behavior in the United States. J Clin Psychiatry. 2022;83(3):21m14090.

- Benson C, Singer D, Carpinella CM, et al. The health-related quality of life, work productivity, healthcare resource utilization, and economic burden associated with levels of suicidal ideation among patients self-reporting moderately severe or severe major depressive disorder in a national survey. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2021;17:111–123.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves new nasal spray medication for treatment-resistant depression; available only at a certified doctor’s office or clinic [cited 2020 Mar 18]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-new-nasal-spray-medication-treatment-resistant-depression-available-only-certified.

- Janssen Pharmaceuticals Inc. SPRAVATO (esketamine) nasal spray prescribing information Titusville, NJMarch 2019 [cited 2022 Mar 28]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/211243lbl.pdf.

- Janssen Pharmaceuticals Inc. SPRAVATO (esketamine) nasal spray prescribing information Titusville, NJJuly 2020 [cited 2022 Mar 28]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/211243s004lbl.pdf.

- Canuso CM, Singh JB, Fedgchin M, et al. Efficacy and safety of intranasal esketamine for the rapid reduction of symptoms of depression and suicidality in patients at imminent risk for suicide: results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(7):620–630.

- Canuso CM, Ionescu DF, Li X, et al. Esketamine nasal spray for the rapid reduction of depressive symptoms in major depressive disorder with acute suicidal ideation or behavior. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2021;41(5):516–524.

- Joshi K, Pilon D, Shah A, et al. Treatment patterns, healthcare utilization, and costs of patients with treatment-resistant depression initiated on esketamine intranasal spray and covered by US commercial health plans. J Med Econ. 2023;26(1):422–429.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 45 CFR 46: pre-2018 requirements [cited 2020 Oct 16]. Available from: https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/regulations/45-cfr-46/index.html#46.101.

- Hedegaard H, Schoenbaum M, Claassen C, et al. Issues in developing a surveillance case definition for nonfatal suicide attempt and intentional self-harm using international classification of diseases, tenth revision, clinical modification (ICD-10-CM) coded data. Natl Health Stat Report. 2018;(108):1–19.

- The Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy (AMCP). AMCP partnership forum: optimizing prior authorization for appropriate medication selection. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2020;26(1):55–62.

- The National Board of Prior Authorization Specialists (NBPAS). What is prior authorization? Oradell, NJ2020 [updated 2020 Dec 15, cited 2023 Apr 5]. Available from: https://www.priorauthtraining.org/prior-authorization/.

- American Medical Association (AMA). 2022 AMA Prior authorization (PA) physician survey 2023. Available from: https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/prior-authorization-survey.pdf

- Janssen. Supporting appropriate payer coverage decisions. [updated 2017 Sep]. Available from: https://www.janssencarepath.com/sites/www.janssencarepath-v1.com/files/supporting-appropriate-payer-coverage-decisions.pdf.

- Szanto K, Dombrovski AY, Sahakian BJ, et al. Social emotion recognition, social functioning, and attempted suicide in late-life depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;20(3):257–265.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Risk evaluation and mitigation strategies | REMS 2021 [cited 2023 Apr 12]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/risk-evaluation-and-mitigation-strategies-rems.

- Voelker J, Cai Q, Daly E, et al. Mental health care resource utilization and barriers to receiving mental health services among us adults with a major depressive episode and suicidal ideation or behavior with intent. J Clin Psychiatry. 2021;82(6):20m13842.

- Fu DJ, Ionescu DF, Li X, et al. Esketamine nasal spray for rapid reduction of major depressive disorder symptoms in patients who have active suicidal ideation with intent: double-blind, randomized study (ASPIRE I). J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81(3):19m13191.

- Ionescu DF, Fu DJ, Qiu X, et al. Esketamine nasal spray for rapid reduction of depressive symptoms in patients with major depressive disorder who have active suicide ideation with intent: results of a phase 3, double-blind, randomized study (ASPIRE II). Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2021;24(1):22–31.

- Sokero TP, Melartin TK, Rytsala HJ, et al. Prospective study of risk factors for attempted suicide among patients with DSM-IV major depressive disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186:314–318.