Abstract

Aims

To investigate the preferences of the Japanese population for government policies expected to address infectious disease outbreaks and epidemics.

Methods

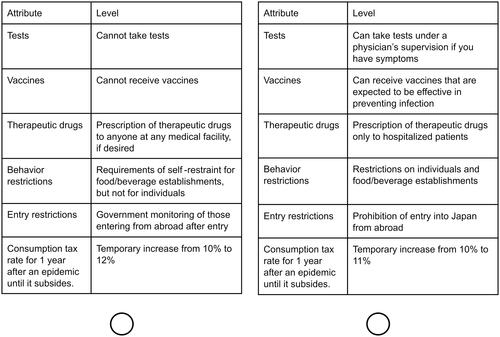

We performed a conjoint analysis based on survey data in December 2022 (registration number: UMIN000049665). The attributes for the conjoint analysis were policies: tests, vaccines, therapeutic drugs, behavior restrictions (e.g. self-restraint or restrictions on the gathering or travel of individuals and the hours of operation or serving of alcoholic beverages in food/beverage establishments), and entry restrictions (from abroad), and monetary attribute: an increase in the consumption tax from the current 10%, to estimate the monetary value of the policies. A logistic regression model was used for the analysis.

Results

Data were collected from 2,185 respondents. The accessibility of tests, vaccines, and therapeutic drugs was preferred regardless of the accessibility level. The value for accessibility of drugs to anyone at any medical facility was estimated at 4.80% of a consumption tax rate, equivalent to JPY 10.5 trillion, which was the highest among the policies evaluated in this study. The values for implementing behavior or entry restrictions were negative or lower than those for tests, vaccines, and drugs.

Limitations

Respondents chosen from an online panel were not necessarily representative of the Japanese population. Because the study was conducted in December 2022, a period during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, the results may reflect the situation at that time and potentially be subject to rapid change.

Conclusions

Among the policy options evaluated in this study, the most preferred option was easily accessible therapeutic drugs and their monetary value was substantial. Wider accessibility of tests, vaccines, and drugs was preferred over behavior and entry restrictions. We believe that the results provide information for policymaking to prepare for future infectious disease epidemics and for assessing the response to COVID-19 in Japan.

Introduction

In the context of the many possible governmental responses to an infectious disease outbreak and epidemic, the preferences of the population are key for policy decision-making. Implementation of strategies scientifically considered to have the best outcomes may be desirable; however, the scientifically best approach may not always be acceptable to the population. During the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, different approaches were implemented globally, such as lockdownsCitation1–3, travel restrictionsCitation1–3, and vaccination recommendationsCitation2–4, with measures and durations varying among countries. The extent to which these policy decisions reflect the public will varies, but the policies likely reflect not only differences in the infection situation and direct impact of disease but also differences in public preferences. Another consideration is that policy implementation imposes a public cost burden. Therefore, it is necessary to identify the degree of a population’s willingness to pay for a policy, as well as their preferences.

Preferences for some policy options have been investigated using conjoint analysis in Japan and other populations, such as factors associated with willingness to undergo vaccinationCitation5–13. Regarding entry from other countries, the factors that reduce negative bias toward foreign travelers, focusing on the effect of health certifications (e.g. vaccination certification, negative test certification) were examined in JapanCitation14. Public preferences and acceptance of various pandemic policies and measures, such as lockdown, behavior restriction, school/office closure, and mask-wearing, have been reported in the United KingdomCitation15, FranceCitation16,Citation17, the United StatesCitation18–20, AustraliaCitation21, PortugalCitation22, GermanyCitation23, and IranCitation24. Public preference for exit strategies from such measures has also been investigated in GermanyCitation25 and the NetherlandsCitation26. To our best knowledge, however, no comprehensive studies have addressed preferences for different policies on widespread infectious disease from both the medical and political approach, and the monetary value of each policy option for the population has not been fully assessed to date.

In Japan, although the COVID-19 pandemic remains ongoing, restrictions on behavior and entry have been relaxed since 2022. Currently, polymerase chain reaction and antigen test kits have become easier to obtain, and vaccines are available to those who want them. Some oral medications are now available; molnupiravir (LagevrioFootnotei), nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (PaxlovidFootnoteii), and ensitrelvir (XocovaFootnoteiii) were approved in Japan under an emergency regulatory approval pathway in December 2021Citation27, February 2022Citation28, and November 2022Citation29, respectively.

For this study, we investigated the preferences of the Japanese population for government policies expected to address infectious disease outbreaks during a pandemic, specifically in terms of monetary value. The policies were based on those implemented for COVID-19 in Japan: tests, vaccines, therapeutic drugs, behavior restrictions (e.g. self-restraint or restrictions on the gathering or travel of individuals and the hours of operation or serving of alcoholic beverages in food/beverage establishments), and entry restrictions (from abroad). To estimate the monetary value of each policy, the amount of an increase in the consumption tax from the current 10% was considered to facilitate realistic assumptions of the cost burden to the study respondents. The study was conducted in December 2022, during the eighth wave of the SARS-CoV-2 virus with the Omicron strain and after various policies had been implemented.

Methods

Study design and participants

This study was based on a conjoint analysis to estimate preferences for government policies related to infectious disease outbreaks and epidemics. Data collection was done by an online survey (15–20 December 2022). Survey respondents were selected from an online panel across Japan managed by an affiliated company of Macromill Carenet, Inc. Members of the panel registered themselves in advance to participate in online surveys. Respondents were both men and women aged 18 − 79 years who agreed to participate in this survey. We planned to collect data from 2,000 respondents with a distribution of age (by 10 years), gender, and area of residence by prefecture similar to that of the Japanese populationCitation30.

Participants of the survey could withdraw from the survey at any time and those who withdrew were excluded from the respondent pool.

Survey methods

At the start of the survey, the following explanation was provided to respondents as the context for their responses:

“We are asking you to answer the following questions assuming a future epidemic of infectious diseases similar to COVID-19. Please answer what do you think should be done about tests, vaccines, behavior restrictions, entry restrictions, and therapeutic drugs against the epidemic. Suppose that the government pays for all the tests, vaccines, and treatments, but instead, the consumption tax is temporarily raised from the current 10% for one year until the epidemic subsides.”

Table 1. Attributes and levels for each attribute in conjoint analysis.

Respondents were also asked for demographic information for subgroup analyses (Tables S1–S22).

Statistical analysis

The respondents’ preference level for each level for each attribute was estimated based on the survey results using conjoint analysis with a logistic regression model. In the model, we assumed that the preference level was equivalent among respondents. The preference level for each level for the attributes was calculated as the difference from the level indicating not available in each attribute, other than the consumption tax rate attribute. Here, the positive values of the preference level indicate that the accessibility or implementation of the policies was preferred, whereas negative values imply that it was not preferred. The preference levels were converted to monetary values as an increase in the consumption tax rate from the current rate (10%) by comparing the preference level for the consumption tax rate attribute. The monetary values as consumption tax rate were also converted to currency values in JPY (approximately JPY 133.44 = $1.00 as of January 2023) based on the total consumption tax revenue of JPY 22 trillion at the 10% tax rate in 2021Citation31. Mean and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for the preference levels and monetary values, and the significance of differences was assessed based on the 95% CIs.

Conjoint analyses were also conducted for subgroups based on demographic data. Subgroup thresholds were set for education, annual income, and household annual income to include approximately 50% of the total respondents. Subgroup analyses were not performed for groups of less than 300 respondents. Data analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 and Microsoft Excel 2016.

Results

Respondents

Of the 3,147 participants who started the survey, 2,185 completed it, including 1,087 men and 1,098 women. The mean age was 50.0 years (standard deviation [SD] 16.3 years). The distribution of respondents by age is shown in . The age and gender distribution was comparable to that of the Japanese population in 2022Citation32 (Table S23). Responses to demographic questions are shown in Tables S1–S22.

Table 2. Distribution of respondents by gender and age.

Estimated value for government policies on infectious disease outbreaks and epidemics

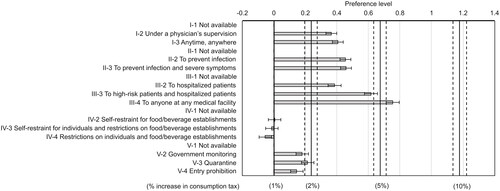

The preference level for each level for each attribute was estimated by conjoint analysis as shown in and . The monetary values for the levels of attributes were calculated as the consumption tax rate by comparing the preference level for each level of attributes to the preference level for the consumption tax rate attribute, as shown in . The value of accessibility of tests, vaccines, and therapeutic drugs to at least some extent was positive when referring to not available. The preference level for the best and second best accessibility for drugs—to anyone at any medical facility and to high-risk patients and hospitalized patients—was 0.7538 and 0.6165, respectively, which was higher than for other attributes. The monetary value of these accessibility levels for drugs was calculated at 4.80% and 3.61% as a consumption tax rate, which is equivalent to JPY 10.5 trillion and JPY 7.9 trillion, respectively. A higher value was indicated for levels associated with easier access or access for more patients to tests and therapeutic drugs; however, no difference was noted for the value of accessibility of vaccines between those to prevent infection and those to prevent both infection and severe symptoms. The value of accessibility of vaccines (2.50% for vaccines to prevent infection and 2.52% for vaccines to prevent infection/severe symptoms, as a consumption tax rate, equivalent to JPY 5.5 trillion and JPY 5.5 trillion) was higher than the accessibility of tests under a physician’s supervision (1.87%) and similar to that of anytime, anywhere (2.16%).

Figure 2. Preference level for each valuable for all respondents. I. Tests, II. Vaccines, III. Therapeutic drugs, IV. Behavior restrictions, V. Entry restrictions. Preference levels for an increase in the consumption tax rate are indicated with an increase rate with a mean (solid line) and 95% confidential intervals (dotted lines). The amount of the increase in the consumption tax rate is indicated in parentheses at the bottom of the graph.

Table 3. Preference level and monetary value of each level for each attribute for all respondents.

Among the levels of behavior restrictions, the lowest value was for the implementation of restrictions on individuals and food/beverage establishments (−0.23% as a consumption tax rate), which was lower than that for no implementation of restraint and restrictions. The mean value of self-restraint for individuals and restrictions on food/beverage establishments was negative (−0.05% as a consumption tax rate); whereas the mean value of self-restraint for food/beverage establishments was positive (0.02%). However, the differences were not significant compared with no implementation of restraint and restrictions. The monetary value of the implementation of any entry restrictions was positive, but it was less than 1% as a consumption tax rate for all levels. The value was the highest for quarantine (0.91% as consumption tax rate), followed by government monitoring (0.76%), and entry prohibition (0.61%).

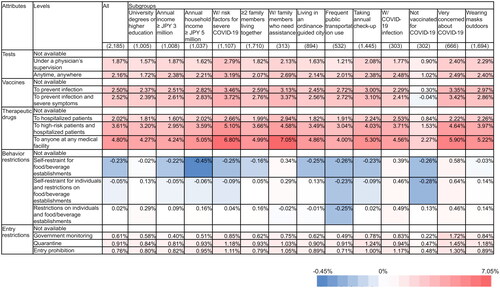

Comparison of the estimated value for government policies by subgroups

shows the estimated monetary value of each level of each attribute as the consumption tax rate for 13 subgroups. Subgroup analyses showed an almost similar order of the values for attribute levels although the amount of the values was slightly different, compared with all respondents for the following subgroups: university degree or higher; annual income ≥ JPY 3 million; annual household income ≥ JPY 5 million; ≥ 2 family members living together; living in an ordinance-guided city; undergoing annual health check-up; and wearing masks outdoors. Among these subgroups, those undergoing annual health check-ups and those wearing masks outdoors exhibited relatively greater value for the accessibility of tests, vaccines, and therapeutic drugs.

Figure 3. The monetary value of each level for each attribute by subgroups. Numbers in parentheses represent the number of respondents in each subgroup. Abbreviation: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; w/, with.

The subgroup with risk factors for severe COVID-19 also had a similar tendency in the order of the values to all respondents; however, the value of accessibility of tests, vaccines, and therapeutic drugs, and implementation of entry restrictions was higher than that in all respondents or other subgroups. The subgroup of respondents living together with family members who need assistance showed a higher value for accessibility of tests, vaccines, and therapeutic drugs, and implementation of entry restrictions, similar to the subgroup with risk factors for severe COVID-19, as well as implementation of behavior restrictions. The subgroup concerned about COVID-19 infection also had a higher value for behavior restrictions and entry restrictions. The subgroup with COVID-19 infection experience showed a positive value for self-restraint and restrictions on behavior.

The subgroup with no COVID-19 vaccination showed a different trend from other subgroups. The value for accessibility of vaccine to prevent infection and severe symptoms was negative in this no-vaccination subgroup, and the value for accessibility of tests and therapeutic drugs were positive for all levels, but the value amounts were almost half of those in other groups. Negative or lower values were indicated for the implementation of behavior restrictions and entry restrictions in the no-vaccination subgroup relative to other subgroups. Higher negative values for the implementation of behavior restrictions were also indicated in the subgroup that utilized public transportation frequently; however, preferences and values for other policies were not substantially different from those of other subgroups.

Of note, we had planned a subgroup analysis for respondents who or whose family members worked in certain fields or industries that may be affected by infectious diseases or disease countermeasures, such as the medical fields, food/beverage industry, and travel industry. However, we could not perform these analyses because of the small number of respondents in each category (152, 125, and 33 respondents, respectively; Tables S10–S12).

Discussion

We evaluated the preferences of the Japanese population for government policies that may be considered in response to infectious disease outbreaks and epidemics, as a monetary value. The policies included tests, vaccines, therapeutic drugs, behavior restrictions, and entry restrictions. Because the Japanese government compensated the industries impacted by behavior restrictions and entry restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic at the national expense, the majority of the respondents were likely aware that they would be subject to a rise in the consumption tax to pay for it. Under this situation, the accessibility of tests, vaccines, or therapeutic drugs was preferred regardless of the level of accessibility, and the value of accessibility of drugs to anyone at any medical facility was the highest among the policies evaluated in this study. Values for implementation of behavior or entry restrictions were negative or lower than those for accessibility of tests, vaccines, and therapeutic drugs. Some differences in these values were found among the subgroups.

Higher values for accessibility of tests, vaccines, and therapeutic drugs seem reasonable, given the expectation of a direct impact on disease prevention or treatment. The monetary value of drugs available to anyone at any medical facility was estimated at 4.80% of a consumption tax rate, which is equivalent to JPY 10.5 trillion. It should be noted that the budget for COVID-19 control in Japan was JPY 77 trillionCitation33, and the national healthcare budget was approximately JPY 43 trillion in 2020Citation34, suggesting that the Japanese population considers a significant cost burden acceptable if therapeutic drugs are available.

In comparison with the accessibility of vaccines (approximately JPY 5.5 trillion as monetary value), the value for accessibility of drugs to anyone at any medical facility or to high-risk patients and hospitalized patients was higher, but the value for accessibility of drugs to hospitalized patients was lower. In the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of patients with severe conditions requiring hospitalisation decreased since the outbreak of the Omicron strain, so respondents may prefer the accessibility of vaccines that can be used for themselves and their families to drugs that can only be used for hospitalized patients. In this survey, each level of the attributes of the drugs mentioned target patients, but the effects of the drugs were not mentioned. Therefore, the preference for accessibility of therapeutic drugs may be influenced by the difference in effects expected by the respondents.

No difference was noted between the accessibility of vaccines to prevent infection versus both infection and severe symptoms, suggesting that vaccines were considered to prevent infection and may not be expected to have an additional effect on the progression to severe symptoms. Another possible reason for the lack of difference between these vaccine accessibilities is that no specific numbers were provided in the options regarding vaccine effects (e.g. the degree to which the infection rate can be reduced). Therefore, it is possible that respondents estimated the prevention effects very highly and thought that the effects on progression to severe symptoms were unnecessary if they did not become infected after vaccination.

The value of securing tests anytime, anywhere was similar to that of vaccines. Considering that taking the test itself has no effect on preventing or curing the disease, the value seems relatively high. This finding may be due to the difficulty of taking tests during the COVID-19 pandemic, especially at the beginning of the pandemic, such that the respondents felt the need to secure the tests. Another possibility is that respondents expected other people to take the tests and act on the test results, rather than expecting the respondents to experience the effects for themselves.

The order of values among the options of tests, vaccines, and therapeutic drugs was mostly similar among the subgroups, except for the no-vaccination subgroup for COVID-19; however, the amount of monetary value differed. A higher monetary value for these options in subgroups of respondents who may be particularly affected by the infection (e.g. risk factors for progression to severe COVID-19, living with family members who need assistance) seems reasonable. Subgroups of respondents who underwent annual health check-ups and those who wore masks outdoors also placed a relatively high value on these options. In the former group, individuals receiving a health check-up may be health-conscious and place a higher value on medical-related policies. Regarding the latter group, since the majority of Japanese wore masks outdoors, as shown by the high percentage (approximately 77.5%) in this study, they possibly wore masks for reasons other than COVID-19 concerns, such as peer pressure and habits. However, given the higher values for the policies found in this study, wearing a mask outdoors may be associated with COVID-19 concerns to some degree. In the no-vaccination subgroup, in addition to negative value for accessibility of vaccines, the monetary values for accessibility of tests or drugs were much lower, almost half of those in the other subgroups. Possible reasons for non-vaccination may be various factors, such as constitutional inability to vaccinate, skepticism about vaccine efficacy, concern about adverse effects, and so on. Nevertheless, given the results for the other attributes, it may be that the no-vaccination subgroup did not consider it necessary to spend money, not only on vaccines but also on other responses to infectious diseases such as COVID-19.

In terms of behavior and entry restrictions, these choices depend on a balance of two factors—self and others. That is, in general, we want to avoid restrictions on ourselves and prefer restrictions on others. Among the options for behavior restrictions, the value of the implementation of restrictions on individuals and food/beverage establishments was negative. Given the positive mean value for the implementation of self-restraint for food/beverage establishments, the respondents may believe that measures related to food/beverages were somewhat effective. Nevertheless, it is suggested that they did not seem to prefer to refrain from their behavior or to be subject to restrictions themselves.

Implementation of any entry restrictions was preferred, although their monetary value was low. A possible reason is, whereas respondents may be somewhat affected by restrictions or self-restraint for individuals or food/beverage establishments, most may not be affected by entry restrictions themselves, so they consider entry restrictions preferable. It is noteworthy that more than 85% of respondents did not travel abroad during 2019 (Table S20). Nevertheless, the strictest restriction—prohibition of entry—had the lowest value among the entry restriction options, suggesting that although entry restriction itself is considered effective and desirable, prohibition of entry is considered undesirable in terms of economic impact. It should also be noted that this survey was conducted at a time when the entry restrictions against COVID-19 had been relaxed since 11 October 2022Citation35, which may have contributed to the low monetary value of entry restrictions.

A relatively high value for the implementation of behavior and entry restrictions was observed among the subgroups living together with family members who need assistance, having COVID-19 infection experience, and being concerned about COVID-19 infection. These subgroups appeared to strongly expect stricter measures against human movement to avoid the risk of infection. In addition, it is possible these subgroups self-regulated their behavior independently of the regulations, in which case they may have had a different preference from other subgroups because the restrictions did not affect their own behavior. In contrast, a negative value was indicated for the implementation of behavior restrictions in the subgroup that utilized public transportation frequently. This may be due to the fact respondents in this group were more likely to socialize daily.

Some differences in preferences and values among subgroups in this study seem consistent with those previously reported. A Japanese study performed a survey in July 2021 and found respondents living with family members with chronic diseases were more likely to accept vaccinationCitation8. Another Japanese study performed a survey in November 2020 and found respondents with moderate/extreme fear of viral infection and those who had routine visits to the healthcare facility (more frequently than monthly) were more willing to be vaccinatedCitation6. These results align with our results, in which a higher value for accessibility of vaccines was indicated by respondents with risk factors for severe COVID-19, those living with family members who need assistance, and those concerned about COVID-19. However, although higher income or higher education was reported to be associated with greater willingness for vaccinationCitation6,Citation8, our study showed no differences in preferences and monetary value based on income or education. This difference is likely due to variations in the survey designs as well as timing. In fact, in the July 2021 study, 36.6% of respondents were already vaccinated, and the percentage of those who did not intend to vaccinate and those who were undecided was 12.5% and 17.9%, respectivelyCitation8. The percentage has since increased—as of December 2022, more than 80% of Japanese adults were vaccinated more than twiceCitation2. Vaccine awareness may have changed with an increase in vaccinated people.

This study had several limitations. First, we collected data for the conjoint analysis through an online survey of individuals who registered in advance for online survey participation. Therefore, the respondents were not necessarily representative of the Japanese population because they had the willingness and ability to participate in the online survey. Second, as described in the introduction, these results may differ from those in other countries. In addition, because the study was conducted in December 2022, a period still during the COVID-19 pandemic, the results may differ from those in a different period. Furthermore, these preferences of the population are potentially subject to rapid change. Third, as mentioned in the discussion, the effects of the therapeutic drug and vaccine options were not clearly stated in the survey. Therefore, the understanding of the effects of these options may differ among respondents, which may influence their choice of options. Including attributes with certain magnitudes of the effects may help to more accurately measure preferences, but we did not include them because we believed that doing so would increase the number of options to be selected and make it more difficult for respondents to respond. Nevertheless, because such effects are unknown at the stage of policy consideration, it would be natural to survey public preferences without limiting the magnitude of the effects. Rather, the respondents may have expected the effects based on their experience with COVID-19, which may have influenced the results. However, we do not believe that this is a particular issue because the population is likely to make judgments based on their own experience with COVID-19 when such preferences are surveyed for future infectious diseases. Fourth, although we conducted subgroup analyses focusing on characteristics that may influence the preference, we may have overlooked some crucial characteristics. For instance, despite the possibility that education for children influences preference, we did not identify respondents with school-aged children for the subgroup analysis. Finally, the reliability of the study results depends on the extent to which respondents understood the questions adequately and responded truthfully.

Conclusions

We estimated the preferences of the Japanese population for government policies to address infectious disease outbreaks and epidemics in 2022. Among the policy options, the preference for accessibility of therapeutic drugs to anyone at any medical facility was the highest, with a monetary value of 4.80% as a consumption tax rate, which is equivalent to JPY 10.5 trillion. The value was higher for accessibility of tests, vaccines, and drugs than that for implementation of behavior and entry restrictions. In particular, the subgroups highly affected by COVID-19 showed higher monetary values for these options.

We believe that the results of this study provide information for considering what kind of measures can be agreed upon by the public for future infectious disease outbreaks and epidemics, as well as for evaluating responses to the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan.

Transparency

Declaration of financial/other relationships

IM, KK, MY and SH are employed by Shionogi & Co., Ltd. IM, KK, MY and SH report company stock in Shionogi & Co., Ltd. KI, TT and CH are employed by Milliman Inc., which has received consultancy fees from Shionogi & Co., Ltd. AI has received consulting fees from Shionogi & Co., Ltd., MSD Inc., Pfizer Japan Inc., Moderna Japan Inc., Gilead Science K.K., and AstraZeneca. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have received an honorarium from JME for their review work but have no other relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

All authors were involved in the conception and design. KI and CH were involved in data analysis. All authors were involved in interpretation of the data. TT drafted the paper, and all authors revised it critically for intellectual content. All authors were involved in the final approval of the version to be published and agree to accountable for all aspects of the work.

Ethics statement

This study was performed following the Declaration of Helsinki and the Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology and the Ministry of Health, Labour and WelfareCitation36. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Health Outcome Research Institute (No. 2022-03) on 11 November 2022, and registered with the University Hospital Medical Information Network Clinical Trial Registry (UMIN000049665). Agreements to participate in the survey were obtained from all respondents online.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (164.5 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors thank Mr. Hidetoshi Ikeoka (Shionogi & Co., Ltd.) for his contribution to the conception and design of this study and the interpretation of the data. The authors also thank Macromill Carenet, Inc. for the execution of the online survey and Enago (www.enago.jp) for the language review, both of which were funded by Shionogi & Co., Ltd.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

i Lagevrio is a registered trade name of MSD, Rahway, NJ, USA.

ii Paxlovid is a registered trade name of Pfizer Inc., New York, NY, USA.

iii Xocova is a registered trade name of Shionogi & Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan.

References

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. The territorial impact of COVID-19: managing the crisis across levels of government. OECD policy responses to coronavirus (COVID-19). Paris (France): Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; 2020.

- Mathieu E, Ritchie H, Rodés-Guirao L, et al. Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) [Internet]. OurWorldInData.org; 2020 [cited 2023 Apr 6]. Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus

- Halperin DT, Hearst N, Hodgins S, et al. Revisiting COVID-19 policies: 10 evidence-based recommendations for where to go from here. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):2084. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-12082-z.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Access to COVID-19 vaccines: global approaches in a global crisis. OECD policy responses to coronavirus (COVID-19). Paris (France): Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; 2021.

- Kawata K, Nakabayashi M. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine preference: a survey study in Japan. SSM Popul Health. 2021;15:100902. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100902.

- Igarashi A, Nakano Y, Yoneyama-Hirozane M. Public preferences and willingness to accept a hypothetical vaccine to prevent a pandemic in Japan: a conjoint analysis. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2022;21(2):241–248. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2022.2016402.

- Ohmura H. Analysis of social combinations of COVID-19 vaccination: evidence from a conjoint analysis. PLoS One. 2022;17(1):e0261426. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0261426.

- Okamoto S, Kamimura K, Komamura K. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and vaccine passports: a cross-sectional conjoint experiment in Japan. BMJ Open. 2022;12(6):e060829. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-060829.

- Schwarzinger M, Watson V, Arwidson P, et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in a representative working-age population in France: a survey experiment based on vaccine characteristics. Lancet Public Health. 2021;6(4):e210–e221. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00012-8.

- Motta M. Can a COVID-19 vaccine live up to Americans’ expectations? A conjoint analysis of how vaccine characteristics influence vaccination intentions. Soc Sci Med. 2021;272:113642. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113642.

- Kreps S, Prasad S, Brownstein JS, et al. Factors associated with US adults’ likelihood of accepting COVID-19 vaccination. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(10):e2025594. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.25594.

- Kaplan RM, Milstein A. Influence of a COVID-19 vaccine’s effectiveness and safety profile on vaccination acceptance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118(10):e2021726118.

- Wang K, Wong EL, Cheung AW, et al. Impact of information framing and vaccination characteristics on parental COVID-19 vaccine acceptance for children: a discrete choice experiment. Eur J Pediatr. 2022;181(11):3839–3849. doi: 10.1007/s00431-022-04586-6.

- Kubo Y, Okada I. COVID-19 health certification reduces outgroup bias: evidence from a conjoint experiment in Japan. Humanit Soc Sci Commun. 2022;9(1):306. doi: 10.1057/s41599-022-01324-z.

- Loría-Rebolledo LE, Ryan M, Watson V, et al. Public acceptability of non-pharmaceutical interventions to control a pandemic in the UK: a discrete choice experiment. BMJ Open. 2022;12(3):e054155. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-054155.

- Sicsic J, Blondel S, Chyderiotis S, et al. Preferences for COVID-19 epidemic control measures among French adults: a discrete choice experiment. Eur J Health Econ. 2023;24(1):81–98. doi: 10.1007/s10198-022-01454-w.

- Blayac T, Dubois D, Duchêne S, et al. What drives the acceptability of restrictive health policies: an experimental assessment of individual preferences for anti-COVID 19 strategies. Econ Model. 2022;116:106047. doi: 10.1016/j.econmod.2022.106047.

- Li L, Long D, Rouhi Rad M, et al. Stay-at-home orders and the willingness to stay home during the COVID-19 pandemic: a stated-preference discrete choice experiment. PLoS One. 2021;16(7):e0253910. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0253910.

- Eshun-Wilson I, Mody A, McKay V, et al. Public preferences for social distancing policy measures to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 in Missouri. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(7):e2116113. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.16113.

- Reed S, Gonzalez JM, Johnson FR. Willingness to accept trade-offs among COVID-19 cases, social-distancing restrictions, and economic impact: a nationwide US study. Value Health. 2020;23(11):1438–1443. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2020.07.003.

- Manipis K, Street D, Cronin P, et al. Exploring the trade-off between economic and health outcomes during a pandemic: a discrete choice experiment of lockdown policies in Australia. Patient. 2021;14(3):359–371. doi: 10.1007/s40271-021-00503-5.

- Filipe L, de Almeida SV, Costa E, et al. Trade-offs during the COVID-19 pandemic: a discrete choice experiment about policy preferences in Portugal. PLoS One. 2022;17(12):e0278526. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0278526.

- Mühlbacher AC, Sadler A, Jordan Y. Population preferences for non-pharmaceutical interventions to control the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: trade-offs among public health, individual rights, and economics. Eur J Health Econ. 2022;23(9):1483–1496. doi: 10.1007/s10198-022-01438-w.

- Homaie Rad E, Hajizadeh M, Yazdi-Feyzabadi V, et al. How much money should be paid for a patient to isolate during the COVID-19 outbreak? A discrete choice experiment in Iran. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2021;19(5):709–719. doi: 10.1007/s40258-021-00671-3.

- Krauth C, Oedingen C, Bartling T, et al. Public preferences for exit strategies from COVID-19 lockdown in Germany-a discrete choice experiment. Int J Public Health. 2021;66:591027. doi: 10.3389/ijph.2021.591027.

- Mouter N, Hernandez JI, Itten AV. Public participation in crisis policymaking. How 30,000 Dutch citizens advised their government on relaxing COVID-19 lockdown measures. PLoS One. 2021;16(5):e0250614. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0250614.

- Lagevrio Capsules 200 mg. Report on the deliberation results. Tokyo (Japan): Pharmaceutical Evaluation Division, Pharmaceutical Safety and Environmental Health Bureau; 2021.

- Paxlovid PACK. Report on the deliberation results. Tokyo (Japan): Pharmaceutical Evaluation Division, Pharmaceutical Safety and Environmental Health Bureau; 2022.

- Xocova Tablets 125 mg. Report on the deliberation results. Tokyo (Japan): Pharmaceutical Evaluation Division, Pharmaceutical Safety and Environmental Health Bureau; 2022.

- Population Estimates. Population estimates/intercensal adjustment of current population estimates intercensal adjustment of current population estimates 2015-2020 table 10 [Internet]. Tokyo (Japan): Statistic Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications; 2022 [cited 2023 May 10]. Available from: https://www.e-stat.go.jp/en/stat-search/files?stat_infid=000032166848

- Data on Tax Revenue [Internet]. Tokyo (Japan): Ministry of Finance; 2022 [cited 2023 Feb 9]. Available from: https://www.mof.go.jp/tax_policy/summary/condition/a03.htm. Japanese.

- Population Estimates. Annual report (October 1, 2022) Table 1 [Internet]. Tokyo (Japan): Statistic Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications; 2023 [cited 2023 May 10]. Available from: https://www.e-stat.go.jp/en/stat-search/files?tclass=000001007604&cycle=7&year=20220

- #Your Corona Budget [Internet]. Tokyo (Japan): Japan Broadcasting Corporation; 2022. [cited 2023 Apr 6]. Available from: https://www3.nhk.or.jp/news/special/covid19-money/. Japanese.

- Annual national medical care expenditure and ratio to gross domestic product (table 1). Estimates of national medical care expenditure. 2020. Tokyo (Japan): Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare; 2022. Japanese.

- Measures for Resuming Cross-Border Travel [Internet]. Tokyo (Japan): Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan; 2022 [cited 2023 Apr 6]. Available from: https://www.mofa.go.jp/ca/cp/page22e_000925.html

- Ethical guidelines for life science and medical research involving human subjects. Tokyo (Japan): Ministry of Education Culture, Sports, Science and Technology; Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare; 2021, partial revision in 2022. Japanese.