Abstract

Background

Antipsychotic discontinuation is common among patients with bipolar disorder, especially when psychotic symptoms are remitted. This analysis describes the prevalence, predictors, and economic impact of antipsychotic discontinuation among patients with bipolar disorder.

Methods

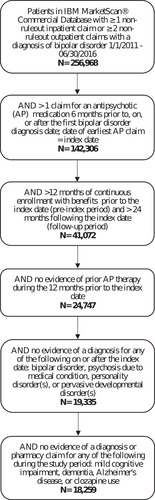

A retrospective, observational study was conducted using administrative claims data in the IBM MarketScan Commercial Database. Patients with ≥1 claim with a diagnosis for bipolar disorder (manic or mixed) and newly-initiating antipsychotic therapy between 1 January 2011 and 30 June 2016 were included. Baseline characteristics were assessed in the 12 months prior to the initiation. Outcomes were assessed during a 24-month follow-up. Discontinuation of antipsychotic therapy was utilized as a predictor of healthcare costs in models adjusted for baseline characteristics. Using limited set of variables in the claims database, predictors of discontinuation were also assessed.

Results

A total of 18,259 commercially-insured patients were identified as initiators of antipsychotics. Common comorbidities among the cohorts included major depressive disorder and dyslipidemia. Discontinuation was very common among these patients (85%). Major depressive disorder, drug abuse, and other substance abuse/dependency were predictive of discontinuation. Controlling for differences in baseline characteristics, discontinuation was associated with 33% higher inpatient and emergency visit costs (p <.001) among those using these services, and 24% higher total healthcare costs (p <.001) for the overall cohort.

Conclusions

Most patients with bipolar mania or mixed states discontinue antipsychotic treatment in less than 2 years. Antipsychotic discontinuation contributes to excess healthcare costs. Future research focusing on the reasons for discontinuation and tailoring disease management based on comorbidities may inform adherence improvement initiatives.

Introduction

Bipolar disorder is a mental illness which poses a significant clinical, humanistic and economic burden. The typical patient experience includes at least one episode of acute mania, along with depressive symptoms which alternate in dramatic mood swingsCitation1. Bipolar disorder is typically diagnosed in teen or early adulthood years and is associated with reduced quality-of-life, functional disability, and poses a substantial economic burden on both patients and the healthcare systemCitation2–5. The overall prevalence of all bipolar disorders in the US is reported to be 2–3% of the adult populationCitation6. Although the exact physiological causes are unknown, evidence suggests that family history plus various environmental stressors increase risk for developing the condition. Implicated environmental stressors include changes in sleep–wake schedules and alcohol and substance abuseCitation1,Citation7,Citation8. Bipolar disorder patients experience higher rates of metabolic conditions, including obesity and diabetes, and psychiatric comorbidities such as anxiety and personality disordersCitation9. These underlying conditions, along with bipolar disorder side-effects, may further complicate the treatment of bipolar disorder and overall disease management.

The goals of bipolar disorder treatment vary by disease state. Initiating antipsychotic pharmacotherapies is recommended for treatment of acute episodes; however, the continuation of antipsychotics into later phases is not as common despite published evidence of efficacy, and continuation on lithium or valproate may also be consideredCitation10. Those who experience two or more episodes are considered to have lifelong bipolar disorder, for which the treatment goal focuses on relieving current symptoms and also preventing future episodes. Maintenance therapy to prevent recurrences should be continued lifelongCitation11. Maintenance therapy is intended to prevent manic or depressive relapse, reduce subsyndromal symptoms, reduce suicide risk, reduce cycling frequency, stabilize mood, and improve functioningCitation12.

Given these long-term treatment goals, adherence to, and long-term continuation of, prescribed antipsychotic therapy is particularly important for this patient population. Non-adherence to therapy among bipolar disorder patients has been associated with relapses and higher healthcare costsCitation5. It is estimated that approximately half of all bipolar disorder patients will be non-adherent to antipsychotic therapyCitation13–16. Limited studies have evaluated the relationship between treatment adherence and economic outcomes in bipolar disease and those studies did not focus on antipsychotic treatment discontinuation. Gianfrancesco et al.Citation17 analyzed PharMetrics claims data and found that antipsychotic adherence was associated with reduced healthcare expenditures among bipolar patients. Broder et al.Citation18 reported full adherence in 32% of bipolar patients who initiated an atypical antipsychotic treatment. The psychiatric hospitalization costs were lower for fully adherent patients ($11,748), than those who were not adherent to antipsychotics ($13,170). The cyclic nature of the symptoms, lack of disease insight, inability to afford medication and other social factors have been hypothesized to contribute to low rates of medication adherenceCitation15,Citation19. There is a need for more in-depth analysis of real-world treatment patterns and identification of predictors of treatment discontinuation so that clinical practice and prescribing of medication may attempt to address these issues to ensure patients are receiving optimal care to reduce the need for expensive healthcare services and reduce the clinical and emotional burden of bipolar disorder symptoms.

The objective of this analysis was to describe the prevalence of antipsychotic treatment discontinuation and the association between treatment discontinuation and healthcare costs among manic or mixed sub-type bipolar disorder patients in a real-world setting. To our knowledge, this is the first analysis to assess treatment patterns of newly-initiated antipsychotic therapy over a 24-month follow-up period among the commercially-insured patients in the US. Treatment discontinuation is an important topic among this patient population, as high rates of treatment discontinuation represent an unmet need in the current pharmacological treatment options available for bipolar disorder.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study used US administrative medical and pharmacy claims data from the IBM MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters Database for the period between 1 January 2011 and 31 December 2016. The Database includes claims of over 100 million patients and their families who are insured through their employers. All study data were fully compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996, and therefore the study did not require approval or a waiver from an institutional review board.

Patient selection criteria

The study population included adult patients with evidence of bipolar disorder, defined as ≥1 inpatient or ≥2 non-diagnostic outpatient medical claims with a diagnosis of manic or mixed-type bipolar disorder: ICD-9-CM 296.0×, 296.4×, 296.6×; ICD-10-CM F31.1×, F31.2, F31.6×, F31.73, F31.74, F31.77, F31.78 between 1 January 2011 and 31 December 2017. Patients were required to have a prescription fill for an antipsychotic medication 6 months prior to, on, or after the first bipolar disorder diagnosis date in the study period; the date of the first antipsychotic claim served as the index date for this analysis. Patients had continuous enrollment in pharmacy and medical benefits during the 12 months preceding and the 24 months following the index date.

To ensure patients were free from prior antipsychotic prescriptions for at least the year prior to the index date, patients with claims for any antipsychotic in the 12 months prior to the index date were excluded. Patients were excluded if they had one or more medical claim for mild cognitive impairment, dementia, or Alzheimer’s disease during baseline, or bipolar disorder, psychosis due to medication condition, or personality disorder(s), pervasive developmental disorder(s) during the follow-up period. Patients with pharmacy claims for clozapine were also excluded as this is not typically prescribed in first-line therapy.

Demographic and baseline clinical characteristics

Demographic characteristics were measured at the index date. Baseline comorbidities were identified by the presence of at least one medical claim with an ICD-9-CM or ICD-10-CM diagnosis code for the condition during the baseline period. Conditions of interest included psychiatric conditions, cardiovascular/metabolic conditions, and substance abuse disorders. Additionally, the Deyo-Charlson Comorbidity Index (DCCI) was calculated to capture the underlying burden of coexisting medical conditionsCitation20. Medications received during the baseline period were identified using National Drug Codes on outpatient pharmacy claims.

Index antipsychotic medication characteristics

Patients were characterized in terms of the first antipsychotic therapy initiated at the index date. Separate from oral medications, we recorded whether patients’ index regimens included a long-acting injectable (LAI) medication as identified by procedure codes on medical claims. Patients with both oral and LAI antipsychotic medications on the index date were classified as having a LAI index treatment regimen. For the purposes of multivariate analysis, index medications were defined as high weight gain risk (HWGR) (olanzapine, chlorpromazine, iloperidone, paliperidone, quetiapine, risperidone, or mesoridazine) or low risk (LWGR) (fluphenazine, haloperidol, perphenazine, thioridazine, thiothixene, aripiprazole, asenapine, lurasidone, ziprasidone, brexpiprazole, trifluoperazine, or cariprazine)Citation21–24. The rationale for considering HWGR vs. LWGR medications as a predictor of antipsychotic adherence has been published elsewhereCitation25.

Study outcomes

Outpatient pharmacy claims were used to assess treatment patterns over the 24-month follow-up. Patients were considered to have discontinued antipsychotic therapy if there was no additional refill for the index treatment regimen 60 days after the run-out date of the previous prescription. This gap length has been extensively applied in claims-based treatment patterns analyses because it offers adequate evidence that two months have passed before obtaining additional medication (not a simple lapse in refilling). Patients were considered discontinued if they were on combination antipsychotics (more than one) and there was no additional refill for one or more components of the index treatment regimen 60 days after the run-out date of the previous prescription. Patients were also considered discontinued if they switched antipsychotics or restarted the same or different antipsychotics but discontinued the index regimens based on a 60 days gap. The discontinuation date was considered the run-out date of the previous prescription. Time to discontinuation (measured in days from initiation of antipsychotic to the first day in the 60+ day gap that qualified as an antipsychotic discontinuation) was also captured.

Medication Possession Ratio (MPR) was calculated to measure treatment adherence during the 24-month follow-up period. The MPR was operationally defined as the sum of the days that the index antipsychotic was supplied divided by the length of the follow-up period (in days) post-index treatment date. This indicates the proportion of days’ supply that a patient should have received or obtained the index medication as prescribed for the entire follow-up period. For those patients who received combination therapy (i.e. two or more antipsychotics), the average number of days’ supply of both medications was taken as the numerator of the MPR, which was subsequently divided by the total number of days in the follow-up period post-index treatment date. For LAI medications, the days of clinical benefit for such injection was used in the absence of days’ supply. We defined adherence as MPR values equal to or greater than 80%, indicating that patients showed continuous medication use for at least 80% of days in the follow-up period.

Healthcare utilization included claims for inpatient admissions, emergency department (ED) visits, outpatient office services, outpatient antipsychotic medication administration, and mental-health-related medication administration and prescriptions. Utilization and cost outcomes considered all claims and were not restricted to those with diagnoses or treatments for bipolar disorder. All-cause health care costs were reported as the mean and median costs during the 24-month follow-up period. All costs were adjusted for inflation using the Consumer Price Index and standardized to 2018 US dollars.

Statistical analysis

We conducted descriptive analyses of stratified patients by medication adherence (MPR ≥0.8 versus <0.8). Differences between strata were assessed using chi-square tests for categorical variables and t-tests or analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables.

We used logistic regression analyses to examine and identify baseline patient characteristics associated with treatment discontinuation. The resulting parameter estimates were used to provide estimates of the odds of discontinuation with 95% confidence intervals. Generalized linear models (GLM) were used to determine incremental cost differences between those who discontinued treatment and those who did not. Cost outcome models used a gamma log link and appropriate distribution functions to handle non-normal cost distributions. For all analyses, p = .05 was the maximum p-value for which differences were considered statistically significant.

Results

Study population

A total of 256,968 patients in the commercially-insured MarketScan database were identified with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, of which 18,259 were new initiators of antipsychotics and met the additional eligibility criteria as listed in . Among these patients, the mean (SD) age of the overall bipolar disorder cohort was 39.0 (16.2) years. displays the comorbidities measured in the baseline period. The most common comorbidities among the entire cohort included major depressive disorder, hypertension, other anxiety, dyslipidemia, and other mood disorder.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics.

Antipsychotic treatment characteristics

The most common atypical medications included quetiapine (34%), aripiprazole (29%), and risperidone (18%). The average days’ supply of the index antipsychotic was just over 1-month supply (mean = 32 days) (). During the 24-month follow-up period, index antipsychotic treatment discontinuation was very common (85%) Among those who discontinued treatment, the mean (SD) time from initiation to discontinuation was 127 (143) days.

Table 2. Index treatment types and treatment patterns.

Post-index healthcare costs and utilization

During the 24-month post-index period, the mean (SD) total healthcare cost was $41,016 ($62,049). The total healthcare costs were significantly different between adherent [$47,218 ($58,912)] and non-adherent [$39,483 ($62,708)] groups (p <.001) (). A third of the patients (33%) had an inpatient admission during the follow-up.

Table 3. Healthcare utilization and costs.

Predictors of antipsychotic discontinuation

Logistic regression models were applied to identify significant predictors of index therapy discontinuation (). Underlying mental health diagnoses, such as major depressive disorder and other anxiety disorder were associated with higher odds of discontinuing therapy (odds ratios (ORs) >1.0 and p-value <.05) (). Diagnoses for drug abuse and other substance abuse/dependency were also predictive of discontinuation. Baseline diagnoses for dyslipidemia was associated with lower odds of discontinuation in the follow-up (OR = 0.85; 95% Confidence Interval (CI) = [0.76–0.95]; p = .005).

Table 4. Predictors of discontinuation: commercially insured.

Predictors of costs

The gamma log-link linear regression model was fit to identify predictors of total healthcare costs during the 24-month follow-up period, with the addition of discontinuation as a covariate. As seen in , increasing age, female sex, weight gain/obesity, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, major depressive disorder, other mood disorder, drug abuse, alcohol abuse, other substance abuse/dependency, increasing MPR, and discontinuation were significantly associated with increased costs (cost ratio [CR] > 1.0 and p <.05), while high weight gain risk was associated with lower costs (CR <1.0 and p <.05). Specifically, controlling for differences in baseline characteristics, discontinuation of antipsychotic therapy was associated with 24% higher total healthcare costs (CR = 1.24; 95% CI = 1.18–1.31; p <.001).

Table 5. Predictors of total healthcare costs during the follow-up period.

Multivariate analysis among patients with non-zero inpatient and/or ED visit costs during the 24-month follow-up was conducted with discontinuation as a covariate (). Weight gain/obesity, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease/events, suicide ideation or behavior, major depressive disorder, other mood disorder, drug abuse, alcohol abuse, high weight gain risk, increasing MPR, and discontinuation were associated with higher inpatient and ED costs (all p <.05). While controlling for differences in baseline characteristics, discontinuation of antipsychotic therapy was associated with 33% higher inpatient + ER costs (CR = 1.33; 95% CI = 1.20–1.48; p <.001).

Table 6. Predictors of hospital setting (inpatient and ED visits) costs during the follow-up period.

Discussion

The findings from this real-world analysis reveal that there are high rates of antipsychotic therapy discontinuation in the 2 years following the therapy initiation. Previous studies have reported similar rates of therapy discontinuation and low rates of patient adherence to medication regimens among the bipolar disorder populationCitation16. Particularly, poor medication adherence is observable among patients with bipolar disorder in outpatient servicesCitation26. Our analysis contextualized these high discontinuation rates in terms of its association with high healthcare utilization and costs. In addition, various underlying medical conditions appeared to impact the patients’ odds of discontinuing treatment, which may help inform initiatives aiming to increase patient adherence to antipsychotic medications.

Over 80% of our patient samples had discontinued antipsychotic therapy during the 24-months following initiation. While claims data does not include reasons for discontinuation or provide insight into whether medication was prescribed but abandoned by the patient versus a clinician no longer prescribing the medication, this real-world data nevertheless provides a glimpse into the real-world experience of bipolar disorder patients. The majority of patients have at least one discontinuation, or gap, in antipsychotic therapy that may be necessary for preventing relapse.

A previous real-world, claims-based analysis reported discontinuation rates within 1 year of a therapy change (i.e. not first-line therapy) in the 70–80% rangeCitation16. This analysis compared those receiving long-acting injectable (LAI) medication versus oral antipsychotics and found significantly better adherence and therapy continuation among those with LAI regimens. Additional studies have identified the utilization of long-acting injectables to be associated with lower rates of therapy discontinuationCitation27. In our analysis, which started at the initial prescription of any antipsychotic (i.e. presumed first-line therapy), long-acting injectables were not frequently prescribed, and therefore were not included in the models to identify predictors of discontinuation.

The predictors of discontinuation identified in this analysis are supported by previously reported results from various study designs. Comorbid alcohol and substance abuse has been associated with increased risk of developing bipolar disorder and relapsesCitation7, as well as increased rates of medication non-adherence and higher healthcare costs in mental health disordersCitation28. Depression has been associated with lower medication adherence for chronic diseases in general, supporting our finding that underlying depression was significantly associated with higher odds of therapy discontinuationCitation29. Major depressive disorder was identified as a comorbidity in 31.3% of bipolar patients. It is likely that some patients with comorbid depression would have changed diagnosis from depression to bipolar disorder over time. However, those with comorbid depression might have received antidepressant treatments, which were not captured separately in this study, but they were considered in total pharmacy costs.

The study results suggest lower odds of discontinuation among patients with an underlying dyslipidemia diagnosis. This finding could possibly be explained by the pre-existing need for daily medication and the relatively lower impact of an additional antipsychotic medication compared to those patients who did not already take daily medication for chronic conditions. In addition, these patients may have been prescribed antipsychotics or antidepressants prior to our baseline period in this analysis, and those prior treatment regimens, and adherence to such regimens, may have led to the development of dyslipidemia, weight gain, or other metabolic side-effects which have been established in prior analyses among bipolar disorder patientsCitation30.

The standard deviations for healthcare costs were larger than the means in both adherent and non-adherent groups. This indicates substantial variations in costs across the study population which closely depend on the heavy health service users. Our findings that patients who discontinue antipsychotic therapy were more costly in the follow-up period are in alignment with previous findingsCitation17,Citation18.

There are a number of inherent limitations associated with administrative claims data used in this analysis. Claims data include the records of health care services submitted by providers for the purpose of reimbursement. Administrative databases are not recorded specifically for research purposes. These types of data have limitations in terms of miscoding and misclassification of disease status as coding errors are common when differential diagnoses have not been ruled out. In observational research based on medical claims, a diagnostic code cannot provide definitive evidence regarding the presence of a medical condition, intervention, or diagnostic procedure. Pharmacy claims which represent the filling of a prescription cannot provide evidence that the medication was taken as prescribed.

Another limitation of the current analysis is that discontinuation was measured during the same time period as healthcare costs, during the 24-month follow-up, so the order of events preceding the increased costs is unknown (i.e. discontinued and then cost increased, or costs increased and then the patient discontinued therapy).

Unmeasured confounders, such as social determinants of health, were not available for analysis and these may be important predictors of discontinuation. Furthermore, weight information was not available in the claims database. Future research incorporating patient and clinician reported outcomes or these important social determinants of health may identify additional predictors of discontinuation that we could not identify in this claims-based analysis. It is noteworthy to mention that the study results may not be fully generalizable to settings outside of the United States due to health insurance system and practice pattern differences.

This real-world analysis provides further insight into antipsychotic therapy discontinuation rates among patients with bipolar disorder and found that discontinuation is associated with significantly higher healthcare costs. Similar to previous research, underlying psychiatric comorbidities, such as anxiety, drug abuse, and depression, were significantly associated with increased odds of treatment discontinuationCitation26. This study did not take into account the impact of co-medications including other psychotropic medications in assessing the relationship between antipsychotic discontinuation and economic outcomes. This should be considered that variations in healthcare utilization and costs may not be attributed solely to antipsychotics discontinuation. Future research focusing on the reasons for discontinuation and patient treatment preferences for the acute and maintenance phases of bipolar disorder therapy may inform medication adherence initiatives to improve patient outcomes.

Transparency

Reviewer disclosures

A reviewer on this manuscript has disclosed that they have received manuscript or speaker’s fees from Astellas, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Elsevier Japan, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Kyowa Yakuhin, Lundbeck Japan, Meiji Seika Pharma, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, MSD, Nihon Medi-Physics, Novartis, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Shionogi, Shire, Sumitomo Pharma, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Tsumura, Viatris, Wiley Japan, and Yoshitomi Yakuhin, and research grants from Eisai, Mochida Pharmaceutical, Meiji Seika Pharma, Shionogi and Sumitomo Pharma. The other peer reviewers on this manuscript have no other relevant financial relationships or otherwise to disclose.

Ethical approval

All database records are statistically de-identified and certified to be fully compliant with US patient confidentiality requirements set forth in the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996. Because this study used only de-identified patient records and did not involve the collection, use, or transmittal of individually identifiable data, this study was exempted from Institutional Review Board approval.

Acknowledgements

None reported.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

FC and RK are employed by Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA and also hold Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA stocks.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from IBM Watson Health. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Hirschfeld RM, Bowden CL, Gitlin MJ, et al. Treatment of patients with bipolar disorder. APA Practice Guidelines 2002. 2010.

- Miller S, Dell’Osso B, Ketter TA. The prevalence and burden of bipolar depression. J Affect Disord. 2014;169 Suppl 1:S3–S11. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(14)70003-5.

- Sylvia LG, Montana RE, Deckersbach T, et al. Poor quality of life and functioning in bipolar disorder. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2017;5(1):10. doi: 10.1186/s40345-017-0078-4.

- Dilsaver SC. An estimate of the minimum economic burden of bipolar I and II disorders in the United States: 2009. J Affect Disord. 2011;129(1–3):79–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.08.030.

- Bessonova L, Ogden K, Doane MJ, et al. The economic burden of bipolar disorder in the United States: a systematic literature review. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2020;12:481–497. doi: 10.2147/CEOR.S259338.

- Harvard Medical School. National Comorbidity Survey (NCS). [cited 2017 Aug 21]. Available from: https://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/ncs/index.php.

- Azorin JM, Perret LC, Fakra E, et al. Alcohol use and bipolar disorders: risk factors associated with their co-occurrence and sequence of onsets. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;179:205–212. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.07.005.

- McIntyre RS, Berk M, Brietzke E, et al. Bipolar disorders. Lancet. 2020;396(10265):1841–1856. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31544-0.

- McIntyre RS, Danilewitz M, Liauw SS, et al. Bipolar disorder and metabolic syndrome: an international perspective. J Affect Disord. 2010;126(3):366–387. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.04.012.

- Jauhar S, Young AH. Controversies in bipolar disorder; role of second-generation antipsychotic for maintenance therapy. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2019;7(1):10. doi: 10.1186/s40345-019-0145-0.

- Gitlin M, Frye MA. Maintenance therapies in bipolar disorders. Bipolar Disord. 2012;14:51–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2012.00992.x.

- Bauer M, Glenn T, Alda M, et al. Trajectories of adherence to mood stabilizers in patients with bipolar disorder. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2019;7(1):19. doi: 10.1186/s40345-019-0154-z.

- Chakrabarti S. Treatment-adherence in bipolar disorder: a patient-centred approach. WJP. 2016;6(4):399–409. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v6.i4.399.

- Lingam R, Scott J. Treatment non-adherence in affective disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002;105(3):164–172. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.1r084.x.

- Jawad I, Watson S, Haddad PM, et al. Medication nonadherence in bipolar disorder: a narrative review. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2018;8(12):349–363. doi: 10.1177/2045125318804364.

- Garcia S, Martinez-Cengotitabengoa M, Lopez-Zurbano S, et al. Adherence to antipsychotic medication in bipolar disorder and schizophrenic patients: a systematic review. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2016;36(4):355–371. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0000000000000523.

- Gianfrancesco FD, Sajatovic M, Rajagopalan K, et al. Antipsychotic treatment adherence and associated mental health care use among individuals with bipolar disorder. Clin Ther. 2008;30(7):1358–1374. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(08)80062-8.

- Broder MS, Greene M, Chang E, et al. Atypical antipsychotic adherence is associated with lower inpatient utilization and cost in bipolar I disorder. J Med Econ. 2019;22(1):63–70. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2018.1543188.

- Mago R, Borra D, Mahajan R. Role of adverse effects in medication nonadherence in bipolar disorder. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2014;22(6):363–366. doi: 10.1097/HRP.0000000000000017.

- Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):613–619. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8.

- Muench J, Hamer AM. Adverse effects of antipsychotic medications. Am Fam Physician. 2010;81(5):617–622.

- Patel KR, Cherian J, Gohil K, et al. Schizophrenia: overview and treatment options. P T. 2014;39(9):638–645.

- Weiss C, Weiller E, Baker RA, et al. The effects of brexpiprazole and aripiprazole on body weight as monotherapy in patients with schizophrenia and as adjunctive treatment in patients with major depressive disorder: an analysis of short-term and long-term studies. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2018;33(5):255–260. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0000000000000226.

- Campbell RH, Diduch M, Gardner KN, et al. Review of cariprazine in management of psychiatric illness. Ment Health Clin. 2017;7(5):221–229. doi: 10.9740/mhc.2017.09.221.

- Khandker R, Chekani F, Limone B, et al. Cardiometabolic outcomes among schizophrenia patients using antipsychotics: the impact of high weight gain risk vs low weight gain risk treatment. BMC Psychiatry. 2022;22(1):133. doi: 10.1186/s12888-022-03746-0.

- Semahegn A, Torpey K, Manu A, et al. Psychotropic medication non-adherence and its associated factors among patients with major psychiatric disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst Rev. 2020;9(1):1–18. doi: 10.1186/s13643-020-1274-3.

- Gentile S. Discontinuation rates during long-term, second-generation antipsychotic long-acting injection treatment: a systematic review. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2019;73(5):216–230. doi: 10.1111/pcn.12824.

- Gerding LB, Labbate LA, Measom MO, et al. Alcohol dependence and hospitalization in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 1999;38(1):71–75. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(98)00177-7.

- Grenard JL, Munjas BA, Adams JL, et al. Depression and medication adherence in the treatment of chronic diseases in the United States: a meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(10):1175–1182. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1704-y.

- Torrent C, Amann B, Sánchez-Moreno J, et al. Weight gain in bipolar disorder: pharmacological treatment as a contributing factor. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2008;118(1):4–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01204.x.