Abstract

Background

While global efforts have been made to prevent transmission of HIV, the epidemic persists. Men who have sex with men (MSM) are at high risk of infection. Despite evidence of its cost-effectiveness in other jurisdictions, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for MSM is neither approved nor reimbursed in Japan.

Method

The cost-effectiveness analysis compared the use of once daily PrEP versus no PrEP among MSM over a 30-year time horizon from a national healthcare perspective. Epidemiological estimates for each of the 47 prefectures informed the model. Costs included HIV/AIDS treatment, HIV and testing for sexually transmitted infections, monitoring tests and consults, and hospitalization costs. Analyses included health and cost outcomes, as well as the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) reported as the cost per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) for all of Japan and each prefecture. Sensitivity analyses were performed.

Findings

The estimated proportion of HIV infections prevented with the use of PrEP ranged from 48% to 69% across Japan, over the time horizon. Cost savings due to lower monitoring costs and general medical costs were observed. Assuming 100% coverage, for Japan overall, daily use of PrEP costs less and was more effective; daily use of PrEP was cost-effective at a willingness to pay threshold of ¥5,000,000 per QALY in 32 of the 47 prefectures. Sensitivity analyses found that the ICER was most sensitive to the cost of PrEP.

Interpretation

Compared to no PrEP use, once daily PrEP is a cost-effective strategy in Japanese MSM, reducing the clinical and economic burden associated with HIV.

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY

HIV remains an epidemic, and men who have sex with men (MSM) are at higher risk of infection. Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is a preventive treatment that can reduce someone's risk of getting infected with HIV and has been shown to provide good value for money. PrEP, however, is neither approved nor reimbursed in Japan. In order to determine the value for money in Japan, an economic model was developed to estimate the number of HIV infections and AIDS cases that could be avoided, along with whether daily use of PrEP among MSM in Japan is cost effective. Findings showed that with use of daily PrEP, the proportion of HIV infections and AIDS cases prevented was 63% and 59%, respectively, across Japan. Over a 30-year time horizon, daily use of PrEP would cost the health system less and be more effective than no use of PrEP. Daily PrEP should therefore be considered for reimbursement in MSM in Japan, given its value for money.

Introduction

Globally, in 2021, an estimated 38.4 million people were living with HIVCitation1. In Japan alone, an estimated 30,000 people were living with HIV in 2017Citation2 (a prevalence of less than 1%); the number of annual new HIV infections and AIDS cases notified is around 1300Citation3. Men who have sex with men (MSM) are at high risk of HIV infectionCitation4. While few data on HIV prevalence in MSM in Japan are available, a study from 2018 estimated the prevalence of HIV among a cohort of MSM in Tokyo to be 3%Citation5; with no change in current interventions, the prevalence of HIV among MSM is estimated to rise to 9% by 2050Citation6. In addition to HIV, in 2018, approximately one-third of the total HIV infections/AIDS cases are identified as new “AIDS cases”, suggesting that a diagnosis of AIDS was made only when a patient sought care for AIDS symptomsCitation3. The occurrence of these cases has resulted in the use of the term “Ikinari-AIDS”, a situation in which an HIV-positive person is diagnosed with AIDS without prior knowledge of being HIV positiveCitation7.

Infection with HIV is a complex chronic disease resulting in significant morbidity, and both HIV and AIDS result in considerable economic burden. A study estimating the socio-economic impact of HIV infection in Japan in 1999 reported that the outpatient costs for HIV treatment ranged from ¥180,000 to ¥216,000 per month with 83% of the total cost going toward antiretroviral therapy (ART)Citation8. While ART is the standard of care for HIV infection, some treatment options, if used prior to exposure, can be used as pre-exposure prophyalxis (PrEP). The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends PrEP as a prevention strategy for people at substantial risk for HIV infection, including MSMCitation9. Oral emtricitabine (FTC)/tenofovir disoproxil (TDF) (known as TRUVADA®) was shown to provide protection against HIV infection in two large clinical trialsCitation10,Citation11, with statistically significant reductions in the incidence of HIV attaining 99% among MSM with daily use of PrEPCitation10. A feasibility study among 124 MSM in Japan found that PrEP effectively prevented HIV infection in a real-world setting, reporting an average adherence rate of >95% and a retention rate at two years of ∼80%, both of which are keys to successful implementationCitation12.

In addition to its clinical efficacy, the economic value of PrEP has been demonstrated to be cost-effective in preventing HIV/AIDS in multiple countriesCitation13–15. While under the current National Health Insurance system FTC/TDF for use as PrEP is not available in JapanCitation6, FTC/TDF is available and approved for the treatment of HIV infectionCitation16. Discussions for the approval of FTC/TDF for PrEP are ongoing at Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (MHLW) committeeCitation17. A previous study highlighted the cost-effectiveness of PrEP among MSM in TokyoCitation18, however, the results of this one prefecture cannot be generalized to other prefectures due to differences in the incidence of HIV. Thus, the objective of this analysis is to assess the cost-effectiveness of daily use of PrEP versus no PrEP use among MSM for Japan and each of its 47 prefectures from the Japanese healthcare perspective.

Methods

Model overview

A Markov model, developed in Microsoft Excel ® with six health states, was used to compare daily use of PrEP to no PrEP use (current standard of care) in a Japanese MSM population from a national healthcare perspective. While a static Markov model structure is limited in that it does not contain dynamic elements reflective of infection risk, modeling good practice states that static models are also acceptable when an intervention is projected to be cost-effective and dynamic effects would further enhance thisCitation19; further, this approach aligns with previous cost-effectiveness analyses in Japan where a discrete-time Markov chain with stationary transition probabilities was usedCitation18. The model time horizon was 30 years, with a cycle length of one month; costs and effects were discounted at 2% per annum, aligning with current guidelines in JapanCitation20.

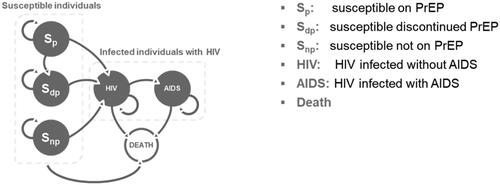

An overview of the model is provided in . Susceptible individuals were MSM over the age of 15, who were HIV-negative and at risk of infection. Within susceptible individuals, three health states were included: “susceptible on PrEP” (Sp), “susceptible discontinued PrEP” (Sdp) and “susceptible not on PrEP” (Snp). In the daily use of PrEP arm, all susceptible individuals started in the Sp health state; in the no PrEP use arm, all susceptible individuals started in the Snp health state. All susceptible individuals (Sp, Sdp, and Snp) could remain susceptible, or become HIV positive (at different rates). For simplicity, individuals who discontinued could not re-start PrEP. As a proportion of MSM may become infected with HIV or develop AIDS, based on current epidemiological estimates in Japan, 6.6% and 2.9% of MSM started in the HIV and AIDS health state, respectivelyCitation7; the remaining proportion started in the “susceptible not on PrEP” state (90.6%). In the model, individuals infected with HIV could develop AIDS, or die from HIV or non-HIV-related causes; individuals with AIDS either remain in the same health state or die from AIDS or non-AIDS-related causes. The model differentiated between HIV and AIDS within the infected health states to account for different death rates, utilities, and health care costs. Transition probabilities used for movement between health states are presented in Table S1.

Model inputs

Population

A population cascade using epidemiological estimates was used to determine the number of eligible patients among MSM who are >15 years of age at risk of HIV infection (Figure S1). The mean age of the patient population was 38 yearsCitation21. The population of the prefectures was taken from the Statistics Bureau of Japan (Table S2)Citation22. The proportion of MSM in the male population over the age of 15 was reported by prefecture; for overall analyses of Japan, a proportion of 4.6% was usedCitation23. The proportion of MSM at high risk of becoming infected with HIV was estimated based on a survey from 2019 regarding MSM in Japan, where it was reported that of the MSM who had multiple sexual partners in the previous 6 months, 55.8% did not use a condomCitation21. Incidence of HIV and AIDS was calculated on an annual basisCitation22. Annual trends of new individuals infected with HIV and the number who develop AIDS were sourced from reports released by the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Health Bureau AIDS Surveillance Committee on 24 August 2021Citation7. The monthly probability of dying from HIV and AIDS was calculated as 0.0374% and 0.1266%, respectivelyCitation24.

PrEP

PrEP inputs considered in the model included coverage rates, efficacy and discontinuation of PrEP. The PrEP coverage rate relates to the proportion of susceptible individuals (MSM without HIV/AIDS) who are considered for daily use of PrEP. In the base case, it was assumed that 100% of susceptible patients would be considered for daily use of PrEP. The efficacy of PrEP was based on the literature and was 99%Citation10,Citation25; the discontinuation rate of PrEP was assumed to be 2% annually.

Costs

All costs are reported in 2022 Japanese yen (¥). The model included direct costs only from the following cost categories: drug costs, monitoring costs and general medical costs.

Drug costs included both the cost of PrEP and the cost of ART (). The cost of PrEP was based on the cost of FTC/TDFCitation26; the cost of ART was derived from published drug prices and reported treatment shares, using a weighted cost calculation, where the daily cost is weighted against treatment share (Table S3)Citation27. Reported drug costs are inclusive of the 30% patient co-payCitation28.

Table 1. Drug costs.

Monitoring costs included costs related to HIV testing and disease monitoring (). It was assumed that HIV testing would be performed every 3 months (4 times per year) for patients in the Sd, Sdp and Snp health state; of these, 0.34% of the positive tests would require confirmatory testing via HIV-1 ribonucleic acid quantification at a unit cost of ¥10,540Citation29. Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and monitoring tests were included with frequencies varying for AIDS and non-AIDS health statesCitation12. Testing costs were applied as a weighted average on a monthly basis. Not all MSM get regularly tested for HIV and STIs. Based on a previous study, 67.2% of those who are susceptible on PrEP, 33.6% of those who are susceptible and discontinued PrEP and 16.8% of those who are not susceptible but not on PrEP would receive STI and HIV testingCitation12; it was assumed that 100% of those in the HIV and AIDS health states were to be tested monthly for HIV and STIs. Of note, test interpretation fees for HIV and AIDS health states were not included for STI tests, as these occur at the same time as monitoring tests, thus, no additional fees were necessary.

Table 2. Disease monitoring and general medical costs.

Monthly hospital costs were calculated using the unit cost and the annual probability of admission for HIV and AIDS (). Given the lack of data, the probability of hospitalization for HIV was assumed to be 5%; the probability of hospitalization for AIDS was based on Japanese literature (88.8%)Citation30.

General medical costs included consultation fees (with separate frequencies for AIDS and non-AIDS health states), prescription fees (included only for those on PrEP or with HIV and/or AIDS) and pharmacy costs (included only for those on PrEP or with HIV and/or AIDS). Pharmacy-related costs were based on the basic charge, dispensing fee and administration costs and were added to drug costs for those on PrEP or with HIV and/or AIDSCitation28.

Utilities

Utilities were defined by the health state. Utilities for susceptible individuals were based on Japanese populations (). The utility for the HIV and AIDS health states was calculated using disutilities from the published literature.

Table 3. Utility inputs.

Analyses

Base case analyses

Results are presented for all of Japan, and individually for each of the 47 prefectures (Supplemental Materials). Both health and cost outcomes are reported. Health outcomes include the proportion of HIV infections and AIDS cases prevented with daily use of PrEP use and the number needed to treat (NNT) to prevent one HIV infection. Cost outcomes include the total costs per individual over the model time horizon, the annual cost to prevent one HIV infection, along with total lifetime costs and cumulative costs of daily use or no use of PrEP. Cost-effectiveness outcomes include life years (LYs), quality-adjusted life years (QALYs), as well as the cost per QALY gained, presented as the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER). An ICER of ¥5,000,000 (equivalent to 37,000 United States dollars [USD]) was considered cost-effectiveCitation31.

Sensitivity analyses

To account for the uncertainty around model parameters, and to test the robustness of the model, both deterministic sensitivity analysis (DSA) and probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA) were conducted. One-way DSA were conducted by varying one parameter at a time by their published variance, where available or by +/-10% of their base case values, where no variance was reported. The DSA is presented as a tornado diagram displaying the ten most influential parameters on the ICER. A multivariate PSA randomly sampled parameters from within chosen distributions over 5000 iterations and is presented as a cost-effective scatterplot with the incremental QALY and incremental cost plotted for each iteration.

Scenario analyses

Three scenario analyses were explored. Given the anticipation of the adoption of PrEP in Japan, alternate PrEP coverage values (90%, 50% and 30%) were explored. As the base case discontinuation rate is an assumption, higher (3%) and lower (1%) annual discontinuation rates were assessed. Finally, alternate time horizons of 10 and 50 years were considered.

Results

Base case analyses

Health outcomes

Across Japan, over the 30-year time horizon, the number of HIV infections and AIDS cases prevented with daily use of PrEP was estimated as 389,466 and 108,735, respectively with 61,205 HIV/AIDS deaths avoided. Compared to no PrEP use, daily use of PrEP resulted in 63% and 59% of HIV infections and AIDS cases prevented, respectively, and 58% of HIV/AIDS deaths avoided. When exploring results by prefecture, the lowest proportion of HIV infections prevented with daily use of PrEP was 48% (Shimane) while the highest proportion of HIV infections prevented was 69% (Iwate) (Table S4). The number needed to treat (NNT) to prevent one HIV or AIDS case for Japan was 3; for the individual 47 prefectures, the NNT ranged from 2 to 11 (Table S4).

Cost outcomes

When considering the daily use of PrEP, the annual cost to prevent one HIV infection in Japan was ¥2,611,764. Across the 47 prefectures, the annual cost to prevent one HIV infection ranged from ¥1,859,684 (Saga) to ¥10,770,472 (Tokushima) (Table S4).

Total costs per individual for Japan, over the time horizon, are presented in . Both disease monitoring costs as well as general medical costs (pharmacy dispensing fees and hospital costs) were lower with daily use of PrEP versus no PrEP use; these lower costs offset the higher drug costs with daily use of PrEP, resulting in cost savings of ¥5,168 over the time horizon. Total incremental costs with daily use of PrEP varied and ranged from cost savings (multiple prefectures) to ¥12,924,493 (Iwate) (Table S5).

Table 4. Cost outcomes per individual over time horizon, Japan.

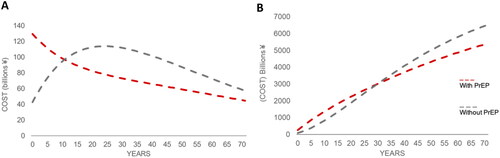

Annual total costs, along with cumulative total lifetime costs, for Japan, are presented in with and without the use of PrEP. As seen in , when considering the annual costs over time, daily use of PrEP becomes cost-saving at year 12 (where annual costs for use of PrEP are less than annual costs for no PrEP use). Cumulative total costs over time for daily use of PrEP are less than no PrEP use after 30 years ().

Cost-Effectiveness outcomes

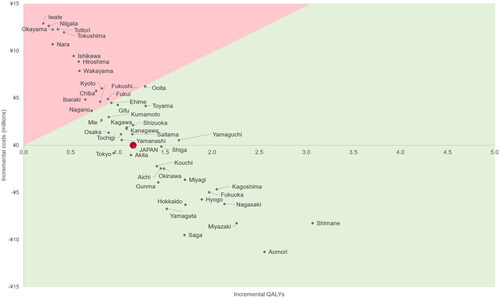

As noted above, across Japan, daily use of PrEP resulted in cost savings. Further, both total LYs and total QALYs were higher, resulting in incremental QALYs of 1.16 compared to no PrEP use (). Thus, daily use of PrEP is considered highly cost-effective at a willingness to pay of ¥5,000,000 per QALY as it is less costly and more effective.

Table 5. Cost-effectiveness results (per individual), Japan.

Across all 47 prefectures, daily use of PrEP always resulted in incrementally more QALYs and cost savings in 18 prefectures (see Table S5 for details). Daily use of PrEP was considered cost-effective at a willingness to pay of ¥5,000,000/QALY in 32 of the 47 prefectures ().

Sensitivity analyses

Sensitivity analyses showed that the results were robust when model parameters were varied. In the DSA, the key driver of the model for ICER was the unit cost of PrEP (Figure S2). Increasing the cost of PrEP by 10% (upper bound) resulted in an ICER of ¥2,443.308, which remains below the cost-effectiveness threshold in Japan; other parameters had minimal impact on the ICER. In the PSA, the mean ICER was ¥77,879; less than 1% of all iterations were above the threshold of <¥5,000,000 per QALY (Figure S3).

Scenario analyses

Scenario analyses for Japan are presented in Table S6. Decreasing PrEP coverage from the base case (100%) decreases the proportion of both HIV infections and AIDS cases prevented; incremental costs are decreased, along with incremental QALYs. However, for all scenarios of PrEP coverage, daily use of PrEP was less costly and more effective than no PrEP use. Lower discontinuation rates (1%) of daily use of PrEP increased incremental costs due to higher total drug costs, resulting in an ICER of ¥393,860 per QALY, which is still considered cost-effective. A shorter time horizon (10 years) resulted in an ICER of ¥26,616,021 per QALY; increasing the time horizon to 50 years resulted in the greatest cost savings.

Discussion

This is the first analysis to investigate the cost-effectiveness of PrEP in each of the 47 prefectures in Japan. The results of this analysis found that among Japanese MSM, daily use of PrEP was cost-effective at a willingness to pay threshold of ¥5,000,000 (37,000 USD) per QALY in 32 of the 47 prefectures. Despite the increase in drug costs, daily use of PrEP resulted in minimal incremental costs due to lower monitoring and general medical costs. Further, after 12 years, it was estimated that annual total costs would be less with daily use of PrEP versus the standard of care (no PrEP use). Results were most sensitive to the cost of PrEP.

While global efforts have been made to prevent the transmission of HIV, the epidemic persists and MSM are disproportionately affected. The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) has set goals to reduce HIV infections and AIDS-related morbidity and mortality by 2030 and has put in place interim 2025 AIDS targetsCitation32. The strategies identified to reach these targets include the ability to access health services, use of combination prevention, people knowing their status, eliminating vertical transmission, initiating treatment, and achieving viral suppression for those on treatmentCitation32. Multiple interventions and strategies have been used to reduce the transmission of HIV, with early interventions including expanding the use of ART through test-and-treatCitation33 and condom useCitation34. It should be noted that while condom use is recognized as a strategy to prevent the transmission of HIV, inconsistent use of condoms is considered an HIV-risk factor among MSMCitation35. A recent prospective study in Tokyo among MSM found that daily use of PrEP alone significantly decreased incidental HIV infections, with no infections among PrEP users after a 2-year follow-upCitation12. In addition to these strategies, a model estimated the impact of behavioral or biomedical interventions on the transmission of HIV among Japanese MSMCitation36. The interventions forecasted to achieve elimination of HIV among MSM by 2050 included an annual number of sexual partners among high-risk MSM less than 9, or condom use rate above 65%, or with HIV testing and treatment rates above 80% or with PrEP coverage rates of more than 10%Citation36.

Ending the epidemic has also been recognized as a highly efficient investmentCitation37. In a global study including the Asia-Pacific region, accelerating the treatment and prevention to reduce new HIV infections and AIDS-related deaths results in added economic and social valueCitation37. A prior publication in Japan found that a PrEP program results in cost savingsCitation18. Using a discrete-time Markov chain over a 30-year time horizon, under a 50% PrEP coverage scenario, a PrEP program was dominant (less costly and more effective) over a program without PrEP; this model did not consider discontinuation among PrEP usersCitation18. Our analysis found similar cost-effectiveness results with daily use of PrEP in 32 of the 47 prefectures, as well as for the overall analysis of Japan, while including discontinuation rates and higher PrEP coverage rates. Despite the growing evidence of the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of PrEP, discussions on its approval are still ongoing in Japan.

As with all economic models, findings should be interpreted in the context of key limitations and assumptions. While this model assumed that coverage with daily use of PrEP use is 100%, it is likely that the adoption of PrEP, even if reimbursed, would increase slowly over timeCitation38. However, as observed in the scenario analyses of lower PrEP coverage, the impact of 100% coverage on cost-effectiveness is conservative given that 100% coverage is associated with higher total PrEP drug costs (versus lower coverage rates and lower associated drug costs). The model also assumed that the risk of infection was constant, whereas, in reality, risk of infection in susceptible individuals would be a function of the proportion of the population infected and may vary with other co-morbidities such as STI, which may increase HIV infectiousnessCitation39. As the benefits of reduced transmission of HIV with daily use of PrEP are not considered in a Markov model, our model may be considered conservative in the number of HIV infections/AIDS cases prevented as the benefits of reduced transmission are not consideredCitation19. Thus, the model structure used in this analysis may underestimate the net benefit of daily PrEP use as it does not capture the indirect reduction in onward HIV transmission. Further, the model assumed that individuals who discontinue PrEP would not re-start; this may not reflect patterns of real-world PrEP use where individuals who discontinue may re-start at a later date. We consider this assumption conservative as allowing individuals who discontinue to restart would increase PrEP use over time. This model only considered the cost of tests for STIs; future work should explore both the impact of uptake of PrEP on rates of STIsCitation40. While every effort was made to use data from Japan, some assumptions were necessary, though sensitivity analyses found that the model was robust against many of these assumptions. Further, while it was important to present a comprehensive view of Japan, including all 47 prefectures individually, it should be noted that the incidence of HIV and AIDS in some prefectures was small and resulted in higher ICERs. It should be noted that the lower observed incidence of HIV and AIDS may be a result of lack of identification of HIV/AIDS positivity; increased testing, with subsequent linkage to care, is a recognized strategy in eliminating new infectionsCitation6,Citation32. Finally, this model did not consider the societal impact of reducing the number of HIV infections from use of PrEP, including a reduction in fear and anxiety surrounding HIV infectionsCitation41.

Use of PrEP contributes to the global strategy of ending the HIV epidemic by supporting the elimination of HIV transmission and decreasing the clinical and economic burden associated with HIV and AIDS. This analysis found that daily use of PrEP among MSM resulted in fewer HIV infections and AIDS cases across all prefectures in Japan. Further, daily use of PrEP was cost-effective across Japan, and in the majority of the prefectures, particularly in those where the incidence of HIV is higher. The approval and reimbursement of PrEP should be considered across Japan as a tool for HIV prevention among MSM.

Transparency

Declaration of financial/other relationships

DM, KH, YN, YP are employees and stockholders of Gilead Sciences. FEM, MC and LB received consulting fees as employees of Maple Health Group for the purpose of this analysis and manuscript. DM and TT have no conflicts to disclose.

Author contributions

DM contributed to the conceptualization of the study design, data collection, data interpretation, and the writing, reviewing and editing of the manuscript. YN contributed to the data acquisition, study design, data interpretation, project administration, and writing, reviewing and editing of the manuscript. DM contributed to the literature search, conceptualization, data interpretation, validation, and writing, reviewing and editing of the manuscript. KH contributed to the study design, data collection, data interpretation, and the writing, reviewing and editing of the manuscript. YP contributed to the project administration, data interpretation, validation, and writing, reviewing and editing of the manuscript. LB contributed to the interpretation, validation, visualization and writing of the manuscript. FEM contributed to the conceptualization, literature search, visualization of data, study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, validation and writing, reviewing and editing of the manuscript. MC contributed to the conceptualization, methods, acquisition and analysis of the data. TT contributed to the supervision, writing and data interpretation. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (583.6 KB)Data availability statement

The data and model informing this analysis are available upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- World Health Organization. HIV 2022 [October 18, 2022]. Available from: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/hiv-aids.

- Nishiura H. Estimating the incidence and diagnosed proportion of HIV infections in Japan: a statistical modeling study. PeerJ. 2019;7:e6275. doi: 10.7717/peerj.6275.

- National Institute of Infectious Diseases. HIV/AIDS in Japan. 2019. IASR. 2021;41:175–176.

- Biello KB, Mimiaga MJ, Santostefano CM, et al. MSM at highest risk for HIV acquisition express greatest interest and preference for injectable antiretroviral PrEP compared to daily, oral medication. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(4):1158–1164. doi: 10.1007/s10461-017-1972-6.

- Takano M, Iwahashi K, Satoh I, et al. Assessment of HIV prevalence among MSM in Tokyo using self-collected dried blood spots delivered through the postal service. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):627. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3491-0.

- Gilmour S, Peng L, Li J, et al. New strategies for prevention of HIV among Japanese men who have sex with men: a mathematical model. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):18187. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-75182-7.

- AIDS Prevention Information Network. Situation in Japan: Committee on AIDS Trends. Quarterly Report 2022 2022. Available from: https://api-net.jfap.or.jp/status/japan/index.html.

- Kimura H. Cost of HIV treatment in highly active antiretroviral therapy in Japan. Nihon Rinsho. 2002;60(4):813–816.

- World Health Organization. Guideline on when to start antiretroviral therapy and on pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV. 2015.

- Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2587–2599. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011205.

- Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. N Engl J Med. 2012; 2012/08/02367(5):399–410. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108524.

- Mizushima D, Takano M, Ando N, et al. A four-year observation of HIV and sexually transmitted infections among men who have sex with men before and during pre-exposure prophylaxis in Tokyo. J Infect Chemother. 2022;28(6):762–766. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2022.02.013.

- Cambiano V, Miners A, Dunn D, et al. Cost-effectiveness of pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men in the UK: a modelling study and health economic evaluation. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):85–94. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30540-6.

- Nichols BE, Boucher CAB, van der Valk M, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV-1 prevention in The Netherlands: a mathematical modelling study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16(12):1423–1429. Decdoi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30311-5.

- ten Brink DC, Martin-Hughes R, Minnery ME, et al. Cost-effectiveness and impact of pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent HIV among men who have sex with men in asia: a modelling study. PLoS One. 2022;17(5):e0268240. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0268240.

- PrEPMAP. PrEP status by country [cited October 24, 2022]. Available from: https://www.prepmap.org/prep_status_by_country#japan.

- Ministry of Health LaW. Requests submitted in Part IV 2021. Available from: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/0000111297.html.

- Yamamoto N, Koizumi Y, Tsuzuki S, et al. Evaluating the cost-effectiveness of a pre-exposure prophylaxis program for HIV prevention for men who have sex with men in Japan. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):3088. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-07116-4.

- Pitman R, Fisman D, Zaric GS, et al. Dynamic transmission modeling: a report of the ISPOR-SMDM modeling good research practices task force-5. Value Health. 2012;15(6):828–834. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2012.06.011.

- Center for Outcomes Research and Economic Evaluation for Health. Guideline for preparing cost-effectiveness evaluation to the central social insurance medical council. (C2H) Nioph, editor. version 3.0 approved by CSIMC on 19th January, 2022; 2022. Available from: https://c2h.niph.go.jp/tools/guideline/guideline_en.pdf

- Research group on the system for providing pre-exposure and post-exposure prophylactic medication for HIV infection. Health, Labor and Welfare Science Research Grant. AIDS Policy Research Project “Questionnaire Survey on PrEP”. 2019.

- Statistics Bureau of Japan. Chapter 2 Population and Households 2017. Available from: https://www.stat.go.jp/english/data/nenkan/66nenkan/1431-02.html.

- Community centers in the Tokyo metropolitan area. Status of HIV/AIDS infection in Japan. 2013.

- Nishijima T, Inaba Y, Kawasaki Y, et al. Mortality and causes of death in people living with HIV in the era of combination antiretroviral therapy compared with the general population in Japan. AIDS. 2020;34(6):913–921. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000002498.

- Underhill K, Morrow KM, Colleran C, et al. Explaining the efficacy of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention: a qualitative study of message framing and messaging preferences among US men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(7):1514–1526. Juldoi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1088-9.

- Gilead Sciences. Data on file. 2022.

- Higasa S, Kojima K, Masuda J. Basic survey for anti-HIV therapy and adherence to anti-HIV drug prescription trend survey at the start of treatment. O-C6-*. Annual Congress of the Japan Society for AIDS Research, et al. 2020.

- Japan National Health Insurance. Prescription fee 2022. Available from: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/12400000/000603756.pdf.

- Kato H, Kanou K, Arima Y, et al. The importance of accounting for testing and positivity in surveillance by time and place: an illustration from HIV surveillance in Japan. Epidemiol Infect. 2018;146(16):2072–2078. doi: 10.1017/S0950268818002558.

- Asahata S, Imamura A, Yanagisawa Y, et al. A study on hospitalization of AIDS patients in the HAART era. JJapanese AIDS Soc. 2013;15:194–198.

- Hasegawa M, Komoto S, Shiroiwa T, et al. Formal implementation of cost-effectiveness evaluations in Japan: a unique health technology assessment system. Value Health. 2020;23(1):43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2019.10.005.

- UNAIDS. Prevailing against pandemics by putting people at the centre. 2020. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/prevailing-against-pandemics_en.pdf

- Montaner JS, Hogg R, Wood E, et al. The case for expanding access to highly active antiretroviral therapy to curb the growth of the HIV epidemic. Lancet. 2006;368(9534):531–536. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69162-9.

- Pinkerton SD, Abramson PR. Effectiveness of condoms in preventing HIV transmission. Soc Sci Med. 1997;44(9):1303–1312. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00258-4.

- Smith DK, Herbst JH, Zhang X, et al. Condom effectiveness for HIV prevention by consistency of use among men who have sex with men in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015; 168(3):337–344. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000461.

- Wang Y, Tanuma J, Li J, et al. Elimination of HIV transmission in Japanese MSM with combination interventions. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2022;23:100467. doi: 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2022.100467.

- Lamontagne E, Over M, Stover J. The economic returns of ending the AIDS epidemic as a public health threat. Health Policy. 2019;123(1):104–108. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2018.11.007.

- van Dijk M, de Wit JBF, Guadamuz TE, et al. Slow uptake of PrEP: behavioral predictors and the influence of price on PrEP uptake among MSM with a high interest in PrEP. AIDS Behav. 2021;25(8):2382–2390. doi: 10.1007/s10461-021-03200-4.

- Kalichman SC, Pellowski J, Turner C. Prevalence of sexually transmitted co-infections in people living with HIV/AIDS: systematic review with implications for using HIV treatments for prevention. Sex Transm Infect. 2011;87(3):183–190. doi: 10.1136/sti.2010.047514.

- Cannon C, Celum C. Sexually transmissible infection incidence in men who have sex with men using HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis in Australia. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22(8):1103–1105. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00284-5.

- Keen P, Hammoud MA, Bourne A, et al. Use of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) associated with lower HIV anxiety among gay and bisexual men in Australia who are at high risk of HIV infection: results from the flux study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2020;83(2):119–125. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000002232.

- Japan National Health Insurance. Price list 2022. Available from: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/12400000/000603751.pdf.

- National Center for Global Health and Medicine. Average cost of inpatient cases [September 28, 2022]. Available from: http://www.hosp.ncgm.go.jp/inpatient/070/index.html.

- Shiroiwa T, Noto S, Fukuda T. Japanese population norms of EQ-5D-5L and health utilities index mark 3: disutility catalog by disease and symptom in community settings. Value Health. 2021;24(8):1193–1202. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2021.03.010.

- Miners A, Phillips A, Kreif N, et al. Health-related quality-of-life of people with HIV in the era of combination antiretroviral treatment: a cross-sectional comparison with the general population. Lancet HIV. 2014;1(1):e32-40–e40. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(14)70018-9.