Abstract

Background and Aim

Benralizumab is a biologic add-on treatment for severe eosinophilic asthma that can reduce the rate of asthma exacerbations, but data on the associated medical utilization are scarce. This retrospective study evaluated the economic value of benralizumab by analyzing healthcare resource utilization (HRU) and medical costs in a large patient population in the US.

Methods

Insurance claims data (11/2016–6/2020) were analyzed. A pre-post design was used to compare asthma exacerbation rates, medical HRU and medical costs in the 12 months pre vs. post index (day after benralizumab initiation). Patients were aged ≥12 years, with ≥2 records of benralizumab and ≥2 asthma exacerbations pre index, and constituted non-mutually exclusive cohorts: biologic-naïve, biologic-experienced (switched from omalizumab or mepolizumab to benralizumab), or with extended follow-up (18 or 24 months).

Results

In all cohorts (mean age 51–53 years; 67–70% female; biologic-naïve, N = 1,292; biologic-experienced, N = 349; 18-month follow-up, N = 419; 24-month follow-up, N = 156), benralizumab treatment reduced the rate of asthma exacerbation by 53–68% (p < .001). In the biologic-naïve cohort, inpatient admissions decreased by 58%, emergency department visits by 54%, and outpatient visits by 58% post index (all p < .001), with similar reductions in exacerbation-related medical HRU in other cohorts. Exacerbation-related mean total medical costs decreased by 51% in the biologic-naïve cohort ($4691 pre-index, $2289 post-index), with cost differences ranging from 16% to 64% across other cohorts (prior omalizumab: $2686 to $1600; prior mepolizumab: $5990 to $5008; 18-month: $3636 to $1667; 24-month: $4014 to $1449; all p < .001). Medical HRU and cost reductions were durable, decreasing by 64% in year 1 and 66% in year 2 in the 24 month follow-up cohort.

Conclusion

Patients treated with benralizumab with prior exacerbations experienced reductions in asthma exacerbations and exacerbation-related medical HRU and medical costs regardless of prior biologic use, with the benefits observed for up to 24 months after treatment initiation.

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY

Benralizumab is a biologic approved as an add-on treatment for severe eosinophilic asthma. Previous real-world studies and clinical trials have shown that benralizumab can reduce the rate of asthma exacerbations and systemic corticosteroid use. However, there is little information on the economic value of benralizumab in real-world patient populations. This study showed that patients with severe asthma in the United States had lower rates of asthma exacerbations after starting treatment with benralizumab. The patients also had fewer asthma exacerbation-related hospitalizations, emergency department visits, and outpatient visits as well as lower medical costs related to asthma exacerbations compared with before the treatment. These benefits were observed in patients who had never taken and those who had been previously treated with biologic therapies, and for up to 24 months after starting benralizumab treatment. These results show that the clinical value of benralizumab translates into reduced medical utilization for patients with severe asthma.

Introduction

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the airways affecting about 8% of the population in the United States (US)Citation1. Although only 5–10% of asthma cases can be classified as severe according to the European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society (ERS/ATS) definitionCitation2, these account for an unduly large proportion of the disease and economic burden. Severe uncontrolled asthma is associated with higher healthcare resource utilization (HRU; including inpatient [IP], outpatient [OP], and emergency department [ED] visits), and individuals with severe disease have medical costs nearly three times higher than those with mild or moderate diseaseCitation3–6. In addition, there are also indirect costs from loss of productivity and absenteeism from workCitation5. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has estimated the cost of severe asthma for the US healthcare system at more than $80 billion annuallyCitation7, and the total cost of uncontrolled asthma in the US in the 20-year period from 2019 to 2038 is projected to be $964 billionCitation8. In this context, symptom control is not just a clinical management goal for severe asthma, but can also have major economic benefits for individuals and society.

The Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) 2022 report recommends several classes of therapy to manage the frequent respiratory symptoms and pulmonary exacerbations that characterize severe uncontrolled asthma. These include bronchodilators (e.g. short-acting [SABAs] and long-acting β-agonists) and inhaled or oral CSs that target airway inflammationCitation9. However, CSs have systemic adverse effects, and their short- and long-term use can increase HRU and costs of severe asthma managementCitation3,Citation10,Citation11. In contrast, monoclonal antibody-based biologic medications that have been approved for asthma treatment target specific inflammatory mechanisms, thereby minimizing the adverse effects of and dependence on systemic CSsCitation12. However, given the more recent introduction of biologics for the treatment of asthma, long-term adverse effects are not well studied and the cost the biologics is much great than the cost of corticosteroids.

Benralizumab is a biologic medication that targets the alpha subunit of the interleukin 5 receptor (IL-5Rα), which leads to the destruction of eosinophils and prevents production of eosinophils, and is indicated as an add-on treatment for patients aged ≥12 years with severe eosinophilic asthmaCitation13. The recommended dose of benralizumab is 30 mg once every 4 weeks for the first 3 doses followed by one every 8 weeks thereafter. Real-world studies have shown that benralizumab significantly decreases the rate of asthma exacerbations and systemic CS use and improves lung function in patients with severe eosinophilic asthmaCitation14–18. Importantly, the demonstrated clinical improvements associated with benralizumab have translated into substantial cost savings. In the ZEPHYR1 study, patients with severe eosinophilic asthma in the US who received benralizumab had fewer exacerbations and reduced oral CS dependence, accompanied by lower HRU and medical costs, compared with the 12-month period before treatment initiationCitation16.

Real-world evidence of the impact of novel therapies on medical HRU can help inform healthcare stakeholders’ decisions. It is especially important to gather data from diverse patient populations that may be excluded from clinical trials and patient populations that are frequently seen in clinical practice, such as biologic-naïve or biologic-experienced patients. In this work, we assessed the economic impact of benralizumab by analyzing medical HRU and direct medical costs in the largest real-world cohort of patients with severe, uncontrolled asthma, defined as ≥2 prior asthma exacerbations, in the US analyzed to date—including patients without or with prior biologic use, and patients with up to 24 months of follow-up—using data from an administrative database. This analysis focused on the impact on medical HRU and costs and did not examine the impact of pharmacy costs.

Methods

The efficacy outcomes from this study for the biologic-experienced and extended follow-up cohorts have been previously publishedCitation14.

Data source

This study used US data from the PatientSource and DiagnosticSource databases supplied by Symphony Health Solutions (SHS) from November 2016 to June 2020. The databases include open medical, laboratory, and pharmacy insurance claims from a range of US payers with healthcare information on approximately 274 million patients annually. Data were available on the medical costs in the claims but information on indirect costs was not available. As this was a retrospective study using deidentified claims data, approval from an ethics committee was not required. These data were used in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration as revised in 2013.

Study design

In this retrospective cohort study, patients with asthma were required to be ≥12 years of age at the time of benralizumab initiation and have ≥2 claims for benralizumab from November 2017 to June 2019. The day after benralizumab initiation was defined as the index date; and the 12-month periods before and after this date were the pre- and post-index periods, respectively. For the extended follow-up cohorts, the follow-up period was expanded to 18 and 24 months post index. A pre–post design was used to compare asthma exacerbations, medical HRU, and medical costs between pre- and post-index periods.

Patient inclusion criteria

Patient inclusion criteria first ensured that patients had data that comprehensively captured encounters in the healthcare system. Eligible patients had ≥1 medical and pharmacy claim in the 12 months before and after the index date (from December 2016 to June 2020) for any reason. Patients were also required to receive benralizumab from physicians or pharmacies with regular reporting, defined as reporting in ≥80% of the included months. Additionally, patients were required to receive care at a hospital for any reason within a 100-mile radius of their first benralizumab administration and the hospital was also required to have ≥50 medical or pharmacy claims per month for 80% of months in the included time period. Inclusion criteria were then applied to select the patient population of interest. Patients in all cohorts were then required to have ≥2 benralizumab records in the claims data, ≥1 asthma diagnosis pre-index, be ≥12 years old on index and have ≥2 asthma exacerbation episodes (to proxy the label indication of severe asthma) during the pre-index period.

Study cohorts

Patients were categorized into non-mutually exclusive cohorts. No comparisons between cohorts were performed given the overlap between them (e.g. there are biologic-naïve and biologic-experienced patients in the 18-month follow-up cohort); all analyses were conducted within cohorts comparing the pre-index period to the post-index period. The biologic-naïve cohort comprised patients with asthma with no biologic use during the pre-index period. The biologic-experienced cohort included patients with asthma with ≥1 record of omalizumab (targeting immunoglobulin E)Citation19 or mepolizumab (targeting IL-5)Citation20 during the pre-index period and no additional biologic use during the post-index period. Patients with asthma in the extended follow-up cohort had 18 or 24 months of data available during the post-index period. Patients in the nasal polyps (NP) cohort had a diagnosis of NPs during the pre-index period (data shown in Supplementary Table S1 and Figures S1 and S2).

Definition of asthma exacerbation

The definition of asthma exacerbations was adapted from ERS/ATS criteria and modified based on clinical input and data availability and are shown in Supplementary Table S2Citation2,Citation14.

Study measures and outcomes

Patient demographics and comorbidities (identified using International Classification of Diseases codes) were described during the pre-index period. Rates of asthma exacerbation per person-year (PPY) and asthma exacerbation-related medical HRU (i.e. unique encounters in the IP, ED, or OP setting) PPY were compared between pre- and post-index periods. Medical costs were estimated from charges using a cost-to-charge ratio of 0.2575 calculated from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) 2018 national hospital inpatient data by dividing the median medical costs by the median medical chargesCitation21. Outliers were identified at the HRU encounter level separately for IP, ED, and OP charges, and replaced using the 1.5 times the interquartile range criterion. Medical costs were annualized for the period from 12 to 18 months post index in the 18-month follow-up group.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were compared with the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, categorical variables with the McNemar test, and rates of asthma exacerbation and exacerbation-related HRU using generalized estimating equations. No imputation was done to address missing data. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the study population

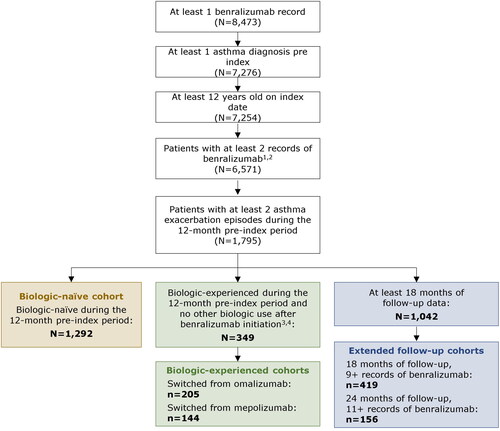

Of the 8,473 patients in the SHS database with at least 1 benralizumab record, 1,292 were included in the biologic-naïve cohort and 349 in the biologic-experienced cohort (). In the latter, 205 patients had switched from omalizumab and 144 had switched from mepolizumab to benralizumab. A total of 419 patients met the inclusion criteria for the 18-month follow-up group; of these patients, 156 were included in the 24-month follow-up group.

Figure 1. Sample selection diagram of patients in the biologic-naïve, biologic-experienced, and 18/24-month follow-up cohorts. 1The record for benralizumab occurring on the day before the index date was included in the count of benralizumab records. 2All patients included in the final sample had at least 1 encounter record every 12 months in the pre- and post-index periods. 3Biologics included dupilumab, mepolizumab, omalizumab, and reslizumab. 4Patients were considered biologic-experienced if they had a new prescription record during the 12-month pre-index period or a prescription record before the 12-month pre-index period with days of supply carrying into the pre-index period.

Baseline characteristics of patients in the biologic naïve cohort are summarized in . Data from the biologic-experienced and extended follow-up cohorts have been previously publishedCitation14,Citation18. The mean age of patients was similar across cohorts (range: 51.2–52.8 years). Most patients were female (67.1–69.5%). The mean Charlson Comorbidity Index was ∼1.5 in all cohorts. The most common cardiovascular comorbidities were hypertension (43.0–44.7%) and hyperlipidemia (28.4–32.0%); the most common infection-related comorbidities were chronic sinusitis (31.5–32.2%) and acute sinusitis (22.3–27.0%); and the most common allergy-related comorbidity was allergic rhinitis (59.1–66.8%). Other common comorbidities included gastroesophageal reflux disease (39.9–40.8%), obesity (31.5–33.0%), and obstructive sleep apnea (25.7–26.5%). NPs were observed in 12.6–14.0% of patients. Oral corticosteroids were commonly used during baseline (95.1%--98.5%).

Table 1. Baseline characteristicsTable Footnotea of patients in the biologic-naïve cohortTable Footnoteb.

In the biologic-naive cohort, patients had a mean number of 4.9 (SD 2.5) records of benralizumab prior to discontinuation. In the cohort of prior omalizumab users, patients had a mean of 5.4 (2.5) records of benralizumab prior to discontinuation and prior mepolizumab users had a mean of 5.5 (2.6) records of benralizumab prior to discontinuation. In the 18-month follow-up cohort, patients received a mean of 7.0 (2.1) records of benralizumab in the 12-month follow-up period, and the 24-month cohort received a mean of 6.7 (2.4) records in the 12-month follow-up period.

Asthma exacerbation reductions with benralizumab

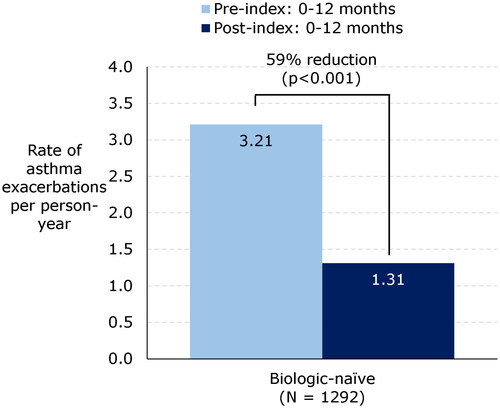

In all cohorts examined, treatment with benralizumab significantly reduced the rate of asthma exacerbations. Among patients without prior biologic treatment (biologic-naïve cohort), the rate of exacerbations decreased significantly by 59%, from 3.21 PPY pre index to 1.31 PPY post index (p < .001; ). Similar decreases were observed among patients in the biologic-experienced cohort (62% and 53% reductions in patients switching to benralizumab from omalizumab and mepolizumab, respectively) and in the extended follow-up cohort (60% reduction at 12 months and 65% reduction at 18 months post index in the 18-month follow-up group; and 59% reduction at 12 months and 68% reduction at 24 months in the 24-month follow-up group) (all p < .001).

Asthma exacerbation-related medical HRU and medical costs with benralizumab

Medical HRU and cost reductions in biologic-naïve and -experienced patients

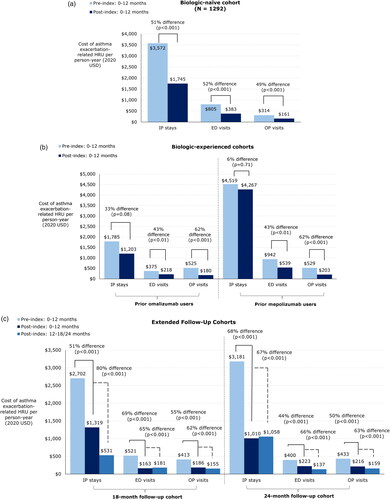

Medical HRU and medical costs related to asthma exacerbations were reduced by benralizumab treatment in all cohorts. In the biologic-naïve cohort, IP admissions decreased by 58%, from 0.51 PPY pre index to 0.21 PPY post index (). Similar decreases were observed for ED visits (from 0.65 to 0.30 PPY, −54%) and OP visits (3.03 to 1.28 PPY, −58%) (both p < .001). Accordingly, exacerbation-related mean total medical costs decreased significantly from $4,691 pre index to $2,289 post index (−51%, p < .001); cost reductions for IP admissions, ED visits,and OP visits ranged from 49% to 52% (all p < .001). The average cost per exacerbation-related HRU during the pre- and post-index periods, prior to the outlier rule being applied, was $9,819 per IP admission, $1,501 per ED visit and $473 per OP visit.

Figure 3. (a) Asthma exacerbation-related HRU and medical costs before and after benralizumab initiation in the biologic-naïve cohort. Abbreviations. ED, emergency department; HRU, healthcare resource utilization; IP, inpatient; OP, outpatient; SD, standard deviation. (b) Asthma exacerbation-related medical costs and HRU before and after benralizumab initiation in the biologic-experienced cohort. Abbreviations. ED, emergency department; HRU, healthcare resource utilization; IP, inpatient; OP, outpatient; SD, standard deviation. (c) Asthma exacerbation-related HRU and medical costs before and after benralizumab initiation in the extended follow-up cohort. Abbreviations. ED, emergency department; HRU, healthcare resource utilization; IP, inpatient; OP, outpatient; SD, standard deviation.

The same trends in medical HRU and costs were observed among patients in the biologic-experienced cohort. Patients switching from omalizumab had a 39% reduction in IP admissions (from 0.28 to 0.17 PPY, p < .05), 42% reduction in ED visits (from 0.31 to 0.18 PPY, p < .01), and 66% reduction in OP visits (3.71 to 1.26 PPY, p < .001) (), with corresponding decreases in mean exacerbation-related medical costs overall (from $2,686 to $1,600, −40%, p < .001) and in the ED (−42%, p < .05) and OP (−66%, p < .001) settings. The cost of IP admissions were similar pre- and post-benralizumab initiation among patients who switched from omalizumab ($1,785 to $1,203, −33%, p = .08). Among patients who switched from mepolizumab, asthma exacerbation-related ED visits (−50%, p < .01) and OP visits (−61%, p < .001) and associated costs (−43%, p < .01 and −62%, p < .001, respectively) were significantly decreased by benralizumab treatment, with a total mean cost reduction from $5,990 to $5,008 (−16%, p < .001). The cost of IP admissions were similar pre- and post-benralizumab initiation among patients who switched from mepolizumab ($4,519 to $4,267, −6%, p = .71).

Medical HRU and cost reductions with extended treatment

The medical HRU and cost benefits of benralizumab were apparent in patients treated over the long term. In the 18-month follow-up group, asthma exacerbation-related medical HRU rates decreased significantly in the 0- to 12-month post-index period, with a 66% reduction in IP admissions (from 0.44 to 0.15 PPY), 58% reduction in ED visits (from 0.42 to 0.18 PPY), and 60% reduction in OP visits (from 3.51 to 1.42 PPY) (all p < .001; ). The decreases in medical HRU rates persisted across all treatment settings in the 12- to 18-month post-index period (60–78% reduction; all p < .001). The medical HRU reductions were accompanied by reductions in exacerbation-related mean medical costs: total costs decreased from $3,636 to $1,667 0–12 months post index (−54%, p < .001), whereas cost reductions for IP admissions, ED visits, and OP visits ranged from 51% to 69% (all p < .001). Similar decreases were also observed at 12–18 months post index, with a 76% decrease in total costs and cost differences ranging from 62% to 80% across treatment settings (all p < .001).

In patients with 24 months of follow-up, asthma exacerbation-related medical HRU rates were decreased by benralizumab treatment across all settings in the 0- to 12-month post-index period (50–74% reduction, all p < .05) and at 12–24 months (57–77% reduction, all p < .01). Exacerbation-related medical costs decreased accordingly: in the 12-month post-index period, total mean costs decreased from $4,014 to $1,449 (−64%, p < .001) and in the 12- to 24-month period, the cost difference from pre to post index was $2,659 (−66%, p < .001), with decreases across treatment settings in the 12- to 24-month period ranging from 63% to 66% (all p < .001).

Discussion

Severe, uncontrolled asthma affects a small proportion of patients with asthma but incurs disproportionately high HRU and medical costs compared with mild/moderate or sub-optimally/well-controlled diseaseCitation3,Citation6,Citation22,Citation23. ZEPHYR2 is the largest real-world study to date of patients with severe asthma treated with a biologic. We previously reported that patients with severe eosinophilic asthma in the ZEPHYR2 study achieved symptom control with benralizumab across a range of blood eosinophil counts, after switching from another biologic, and for up to 24 months post indexCitation14. In this study, we analyzed the economic impact of this effect in a large population of patients with diverse profiles (biologic-naïve or -experienced) or who were evaluated after 18 or 24 months of follow-up. While the impact of pharmacy costs was not considered, the results show that the decrease in the rate of asthma exacerbations with benralizumab was accompanied by reductions in exacerbation-related medical HRU and medical costs. These findings confirm the medical cost reductions associated with benralizumabCitation16. These results were also similar to a European study which found a 57% reduction in hospitalizations after initiation of an anti-IgE and a 71% reduction in hospitalizations after initiation of an anti-IL5/5RCitation24. This study demonstrates for the first time in real-world patients with different biologic treatment histories that the medical HRU and medical cost reductions are long-lasting.

The use of systemic CS to reduce the frequency of exacerbations that characterize severe asthma can lead to a variety of complications and increase medical HRU and healthcare costsCitation3,Citation5,Citation10,Citation11. A dose-response relationship between systemic CS use and the risk of developing complications—and use of associated healthcare resources—has been reportedCitation10,Citation11. In a previous retrospective claims-based study of patients with asthma in the US, frequent severe exacerbations or use of rescue medications including CSs was associated with a higher probability of IP admissions and ED visits and more frequent use of OP services; moreover, 1-year total healthcare costs were increased 1.5 foldCitation5. Conversely, achieving asthma symptom control can be cost-savingCitation25,Citation26. We previously showed that in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma receiving benralizumab, the rate of exacerbations was decreased by 52–68% and the use of oral CSs by 12–20% across different cohorts of patientsCitation14. The decrease in exacerbation rate with benralizumab was confirmed in this study, and was accompanied by lower medical HRU and total medical costs in both biologic-naïve and -experienced patients. Thus, by decreasing the rate of exacerbations, benralizumab not only has clinical value but may also help to reduce medical HRU for patients with severe asthma.

A large proportion of patients with severe asthma treated with benralizumab achieve clinical remissionCitation27, which could diminish medical HRU and healthcare costs over the long term. In our analysis, exacerbation-related medical costs calculated over a 24-month period decreased from $4,014 pre index to $1,449 in the first year and $1,355 in the second year, with decreases observed across all treatment settings. Asthma exacerbation-related medical HRU rates were also decreased by up to 77% with benralizumab after 24 months. Thus, benralizumab treatment of severe asthma led to substantial long-term reductions in medical costs, as evidenced by the greater decrease observed from 12–24 months as compared with 0–12 months after benralizumab initiation. This long-term medical cost savings associated with benralizumab could have important implications for stakeholders.

Switching between biologics is a treatment option for severe asthma patients who are refractory or show suboptimal response to an initial biologicCitation28–30. In this study, the rate of exacerbations decreased by 62% and 53% in patients switching to benralizumab from omalizumab and mepolizumab, respectively. No comparisons between benralizumab and omalizumab or mepolizumab were conducted in this study. Patients switching from omalizumab had a 66% reduction in OP visits, with a 40% decrease in exacerbation-related total medical costs. Decreases in medical HRU and total medical costs were also observed for patients who switched from mepolizumab. While the reduction in total medical costs was lower than what was observed in the biologic-naïve cohort, this may be related to the prior biologic treatment’s impact on medical costs during the pre-index. These medical HRU and cost results are supported by findings from other studies. Patients with severe eosinophilic asthma who were refractory to omalizumab, mepolizumab, or reslizumab showed a significant improvement in asthma control, as evidenced by decreases in the number of exacerbations, CS use, and HRU up to 12 months after switching to benralizumabCitation31–33. Collectively, the evidence from this study and others indicates that optimizing treatment regimens by switching from another biologic to benralizumab can lead to clinical improvement, which can in turn decrease the use of healthcare resources.

Strengths and limitations

This study builds on real-world evidence of the efficacy of benralizumab in patients with severe eosinophilic asthmaCitation14 by showing that the clinical benefits translate into reductions in medical HRU and medical costs. This was demonstrated in diverse patient cohorts and over a long follow-up period. The large claims-based data provided a robust sample of patients who are likely to be representative of the population of patients with severe, uncontrolled asthma in the US who initiate benralizumab. Although the data were not closed, stability rules were carefully implemented to comprehensively capture patients’ encounters. Nonetheless, there were also certain limitations to this study. First, a main limitation is that pharmacy costs were not considered in the current analysis. After observing consistent asthma exacerbation rate reductions among patients treated with benralizumab across patient populations, we set out to understand benralizumab’s impact on medical costs as a result of its real-world effectiveness. However, an evaluation of total healthcare costs including pharmacy costs would be valuable, especially given the high cost of biologics, to understand the total healthcare costs rather than medical benefit. Second, as patients were required to be active in the data for at least 24 months in the extended cohort and 12 months in the other cohorts, those with <24 and <12 months, respectively, of activity regardless of the reason (e.g. a change in employment status or healthcare provider) were excluded; therefore, the generalizability of the findings may be limited if these patients differed from the overall population who initiated benralizumab. Third, we were unable to directly identify patients with severe eosinophilic disease from the data; therefore, although patients in the primary cohort had to have ≥2 asthma-related exacerbations prior to the index date to serve as a proxy for the severe eosinophilic asthma population per the benralizumab product labelCitation13, the results may not be generalizable to individuals with <2 exacerbations. A further study evaluating the population prescribed benralizumab, such as the number of exacerbations and severity of asthma, would be beneficial to understand its real-world use. Fourth, not all variables of interest were available in the claims data; for example, medical costs were estimated from charges using a charge-to-cost ratio from HCUP, although this was consistently applied to both pre- and post-index costs. Additionally, indirect costs of metrics that would allow us to estimate indirect costs, such as absenteeism, were not available in the claims data. Fifth, the pre-post study design could not control for possible temporal changes that may have occurred in the absence of benralizumab treatment. However, this study did not include a comparison group to non-benralizumab users so bias due to confounding is not relevant in this study. Last, claims data do not include information on first-dose samples of benralizumab given to patients that could potentially impact pre- and post-benralizumab asthma exacerbation rates and other outcomes.

Conclusions

The results from this study of a real-world patient population in the US highlight the clinical and medical cost benefit of benralizumab for the treatment of severe asthma. Specifically, patients treated with benralizumab who had prior exacerbations experienced reductions in asthma exacerbations and related medical HRU and medical costs regardless of prior biologic use, with the benefits observed for up to 24 months after treatment initiation. Given the considerable disease and medical cost burden of severe, poorly controlled, or uncontrolled asthma, our findings can inform clinical management decisions to ensure optimal patient care.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

AstraZeneca funded this study, and participated in the study design, data collection, data analysis, and data interpretation. AstraZeneca reviewed the publication, without influencing the opinions of the authors, to ensure medical and scientific accuracy, and the protection of intellectual property. The authors had access to all data in the study, and had the final responsibility for the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

DJM received consultant/speaker fees from AstraZeneca, GSK, Amgen, Sanofi/Regeneron.

FM, EC, DY, and KB are employees of Analysis Group, Inc., a consulting company that has provided paid consulting services to AstraZeneca, which funded the development and conduct of this study and manuscript. Joshua Young was an employee of Analysis Group, Inc. at the time this study was conducted.

DC and YC are employees of AstraZeneca and own stock/stock options in AstraZeneca.

EG was an employee of AstraZeneca at the time this study was conducted and owns stock/stock options in AstraZeneca.

Author contributions

YC: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft preparation, Writing—review and editing. DJM: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft preparation, Writing—review and editing. FM: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data validation, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft preparation, Writing—review and editing. EEC: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data validation, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft preparation, Writing—review and editing. DY: Data validation, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft preparation, Writing—review and editing. JAY: Data validation, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft preparation, Writing—review and editing. KAB: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft preparation, Writing—review and editing. EG: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing—review and editing. DC: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft preparation, Writing—review and editing.

All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have received an honorarium from JME for their review work but have no other relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Previous presentations

Part of the material in this manuscript was presented at the American College of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology Annual Scientific Meeting held on November 4–8, 2021 in New Orleans, LA, USA; American Academy of Allergy Asthma & Immunology Annual Meeting held on February 25–28, 2022 in Phoenix, AZ, USA; Eastern Allergy Conference held on June 2–5, 2022 in Palm Beach, FL, USA; and CHEST Annual Meeting held on October 16–19, 2022 in Nashville, TN, USA as a poster presentation.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (58 KB)Acknowledgements

Medical writing assistance was provided by Janice Imai, an employee of Analysis Group, Inc., and funded by AstraZeneca.

References

- Pate CA, Zahran HS, Qin X, et al. Asthma surveillance—United States, 2006–2018. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2021;70(5):1–32. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss7005a1.

- Holguin F, Cardet JC, Chung KF, et al. Management of severe asthma: a European respiratory society/American thoracic society guideline. Eur Respir J. 2020;55(1):1900588. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00588-2019.

- Barry LE, Sweeney J, O’Neill C, et al. The cost of systemic corticosteroid-induced morbidity in severe asthma: a health economic analysis. Respir Res. 2017;18(1):129. doi: 10.1186/s12931-017-0614-x.

- Chastek B, Korrer S, Nagar SP, et al. Economic burden of illness among patients with severe asthma in a managed care setting. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2016;22(7):848–861. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2016.22.7.848.

- Settipane RA, Kreindler JL, Chung Y, et al. Evaluating direct costs and productivity losses of patients with asthma receiving GINA 4/5 therapy in the United States. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019;123(6):564–572. e3. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2019.08.462.

- Song HJ, Blake KV, Wilson DL, et al. Medical costs and productivity loss due to mild, moderate, and severe asthma in the United States. J Asthma Allergy. 2020;13:545–555. doi: 10.2147/JAA.S272681.

- Nurmagambetov TA, Krishnan JA. What will uncontrolled asthma cost in the United States? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200(9):1077–1078. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201906-1177ED.

- Yaghoubi M, Adibi A, Safari A, et al. The projected economic and health burden of uncontrolled asthma in the United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200(9):1102–1112. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201901-0016OC.

- Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA). Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention. 2021. https://ginasthma.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/GINA-Main-Report-2022-FINAL-22-07-01-WMS.pdf

- Dalal AA, Duh MS, Gozalo L, et al. Dose-response relationship between long-term systemic corticosteroid use and related complications in patients with severe asthma. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2016;22(7):833–847. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2016.22.7.833.

- Lefebvre P, Duh MS, Lafeuille M-H, et al. Acute and chronic systemic corticosteroid–related complications in patients with severe asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136(6):1488–1495. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.07.046.

- Calzetta L, Aiello M, Frizzelli A, et al. Oral corticosteroids dependence and biologic drugs in severe asthma: myths or facts? A systematic review of Real-World evidence. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(13):7132. doi: 10.3390/ijms22137132.

- FASENRA (benralizumab) Prescribing information. AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP. Wilmington. 2021.

- Carstens D, Maselli DJ, Mu F, et al. Largest real-world effectiveness study of benralizumab for severe eosinophilic asthma: ZEPHYR 2. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2023;11(7):2150–2161.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2023.04.029.

- Charles D, Shanley J, Temple SN, et al. Real‐world efficacy of treatment with benralizumab, dupilumab, mepolizumab and reslizumab for severe asthma: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2022;52(5):616–627. doi: 10.1111/cea.14112.

- Chung Y, Katial R, Mu F, et al. Real-world effectiveness of benralizumab: results from the ZEPHYR 1 study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2022;128(6):669–676. e6. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2022.02.017.

- Kayser MZ, Drick N, Milger K, et al. Real-world multicenter experience with mepolizumab and benralizumab in the treatment of uncontrolled severe eosinophilic asthma over 12 months. J Asthma Allergy. 2021;14:863–871. doi: 10.2147/JAA.S319572.

- Menzella F, Fontana M, Galeone C, et al. Real world effectiveness of benralizumab on respiratory function and asthma control. Multidiscip Respir Med. 2021;16(1):785. doi: 10.4081/mrm.2021.785.

- XOLAIR (omalizumab) Prescribing information. Genentech, South San Francisco. 2021.

- NUCALA (mepolizumab) Prescribing information. GlaxoSmithKline LLC, Philadelphia. 2022.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). HCUPnet - Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Rockville, MD. 2022. https://hcupnet.ahrq.gov/

- Reibman J, Tan L, Ambrose C, et al. Clinical and economic burden of severe asthma among US patients treated with biologic therapies. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2021;127(3):318–325. e2. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2021.03.015.

- Kerkhof M, Tran TN, Soriano JB, et al. Healthcare resource use and costs of severe, uncontrolled eosinophilic asthma in the UK general population. Thorax. 2018;73(2):116–124. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2017-210531.

- Pfeffer PE, Ali N, Murray R, et al. Comparative effectiveness of anti-IL5 and anti-IgE biologic classes in patients with severe asthma eligible for both. Allergy. 2023;78(7):1934–1948. doi: 10.1111/all.15711.

- Nguyen HV, Nadkarni NV, Sankari U, et al. Association between asthma control and asthma cost: results from a longitudinal study in a primary care setting. Respirology. 2017;22(3):454–459. doi: 10.1111/resp.12930.

- López-Tiro J, Contreras-Contreras A, Rodríguez-Arellano ME, et al. Economic burden of severe asthma treatment: a real-life study. World Allergy Organ J. 2022;15(7):100662. doi: 10.1016/j.waojou.2022.100662.

- Menzies-Gow A, Hoyte FL, Price DB, et al. Clinical remission in severe asthma: a pooled post hoc analysis of the patient journey with benralizumab. Adv Ther. 2022;39(5):2065–2084. doi: 10.1007/s12325-022-02098-1.

- Menzies-Gow AN, McBrien C, Unni B, et al. Real world biologic use and switch patterns in severe asthma: data from the international severe asthma registry and the US CHRONICLE study. J Asthma Allergy. 2022;15:63–78. doi: 10.2147/JAA.S328653.

- Numata T, Araya J, Miyagawa H, et al. Effectiveness of switching biologics for severe asthma patients in Japan: a single-center retrospective study. J Asthma Allergy. 2021;14:609–618. doi: 10.2147/JAA.S311975.

- Panettieri RA, Jr Ledford DK, Chipps BE, et al. Biologic use and outcomes among adults with severe asthma treated by United States subspecialists. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2022;129(4):467–474.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2022.06.012.

- Fernández AG-B, Gallardo JFM, Romero JD, et al. Effectiveness of switching to benralizumab in severe refractory eosinophilic asthma. J Asthma Allergy. 2022;15:727.

- Jackson DJ, Burhan H, Menzies-Gow A, et al. Benralizumab effectiveness in severe asthma is independent of previous biologic use. J Allergy Clin Immunol Prac. 2022;10(6):1534–1544.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2022.02.014.

- Martínez-Moragón E, García-Moguel I, Nuevo J, et al. Real-world study in severe eosinophilic asthma patients refractory to anti-IL5 biological agents treated with benralizumab in Spain (ORBE study). BMC Pulm Med. 2021;21(1):417. doi: 10.1186/s12890-021-01785-z.