Abstract

Aims

An analysis of the budget impact of using a bovine pericardial aortic bioprosthesis (BPAB) or a mechanical valve (MV) in aortic stenosis (AS) patients in Romania.

Materials and methods

A decision-tree with a partitioned survival model was used to predict the financial outcomes of using either a BPAB (the Carpentier-Edwards Perimount Magna Ease Valve) or MV in aortic valve replacement (AVR) procedure over a 5-year period. The budget impact of various resource consumption including disabling strokes, reoperations, minor thromboembolic events, major bleeding, endocarditis, anticoagulation treatment and monitoring, and echocardiogram assessments were compared for both types of valves. One-way sensitivity analyses (OWSA) were conducted on the input costs and probabilities.

Results

The use of BPAB compared to MV approaches budget neutrality due to incremental savings year-on-year. The initial surgical procedure and reoperation costs for BPAB are offset by savings in acenocoumarol use, disabling strokes, major bleeding, minor thromboembolic events, and anticoagulation complications. The cost of the initial procedure per patient is 460 euros higher for a BPAB due to the higher valve acquisition cost, although this is partially offset by a shorter hospital stay. The OWSA shows that the total procedure costs, including the hospital stay, are the primary cost drivers in the model.

Limitations

Results are limited by cost data aggregation in the DRG system, exclusion of costs for consumables and capital equipment use, possible underestimation of outpatient complication costs, age-related variations of event rates, and valve durability.

Conclusions

Adopting BPAB as a treatment option for AS patients in Romania can lead to cost savings and long-term economic benefits. By mitigating procedure costs and increasing anticoagulation treatment costs, BPAB offers a budget-neutral option that can help healthcare providers, policymakers, and patients alike manage the growing burden of AS in Romania.

Introduction

One of the most common valvular illnesses in Europe is aortic stenosis (AS)Citation1. Symptomatic AS has a poor prognosis in Romania, as it does throughout Europe; therefore, early management is suggested for patients with a high gradient, regardless of left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF)Citation2. Although epidemiological data on AS in Romania is unavailable, results from a meta-analysis undertaken in 27 European countries, the United States, and Canada estimated the prevalence of severe AS in the population older than 65 to be 1.34%, 1.3%-1.4% in the population aged 65–74 years, and 2.8–4.6% in the population aged 75+Citation2,Citation3. Another two meta-analyses in Europe, the United States, and Australasia up to 2017, reported a prevalence of AS of 2.8% in those 60–74 years old and 12.4%–13.1% in those 75 and olderCitation4,Citation5. In Sweden, results from population-based cohort research showed that while the prevalence was 0.2% in those aged 50–59 and 1.3% in those aged 60–69, it was substantially larger (3.9% and 9.8%, respectively) in those aged 70–79 and 80+Citation6. The prevalence of AS is also increasing due to aging and better access to accurate diagnosisCitation1,Citation7–10.

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of mortality in Romania with life expectancy (74.2 years, 2020) among the lowest recorded in Europe (average 80.6 years, 2020)Citation11. In Europe, the age-standardized death rate (ASDR) for AS in both males and females aged above 45 years of age has increased by an average of 164% from 2000 to 2017Citation9. In Romania, the ASDR change was 46% in males and 91% in females, lower compared to Europe, which may be due to under-reporting and a lower AS diagnosis rateCitation9.

Romania has a compulsory social health insurance (SHI) system governed by the Ministry of Health (MoH) and administered by the National Health Insurance House (NHIH) with a National Health Insurance Fund (NHIF) based on payments of contributionsCitation11,Citation12. The national program of cardiovascular diseases in Romania provides AS patients with treatment coverage including surgical intervention, at an average annual cost per adult patient treated by cardiovascular surgery at 8,187 lei (EUR 1,670, 2023)Citation13. Although health expenditure increased in the last decade to 4.6% of gross domestic product (GDP) (and is estimated to increase to 6.9% by 2028Citation14) it still remains the second lowest in EuropeCitation11,Citation12. Out-of-pocket (OOP) payments in Romania are dominated by pharmaceutical and medical device costs (per capita spending of EUR 353, 2019)Citation11.

The number of AS patients undergoing either surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) or transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) has significantly increased, as there are no medical therapies available to influence the natural history of ASCitation15,Citation16. The long-term safety and effectiveness of BPAB has been established in various studies and have shown some consistent resultsCitation17–20. Mortality rates vary across the studies, (2–2.8%) with actuarial survival rates averaging 73% ± 2%, 59% ± 3% and 35% ± 5% after 10, 15 and 20 years of follow-up, respectivelyCitation18–20. Reoperation rates were found to be higher in patients who received BPAP compared to MV in all studiesCitation17–20. Patients given a bioprosthesis had a lower risk for bleeding and stroke compared to MVCitation17,Citation20, and the expected valve durability is 19.7 yearsCitation18. According to clinical practice guidelines and research findings, bioprosthetic valves necessitate regular echocardiogram surveillance, shorter hospital stays, and eliminate the need for prolonged anticoagulation therapy typically required with MVCitation16,Citation21–23. While the initial cost of BPAB (the Carpentier-Edwards Perimount Magna Ease Valve) for AS patients in Romania may be higher than MV, there is currently a lack of research on the overall budget impact when considering the potential cost offsets in outcomes.

Health technology assessment (HTA) among European countries includes pharmaceuticals, medical devices, procedures, and organizational aspects of healthcare. In Romania, an HTA agency was established in 2012 by the MoH and since 2014 is coordinated by the National Agency for Medicines and Medical Devices (NAMMD). The MoH provides an evaluation methodology based on a scorecard system from assessment decisions in other countries, rather than an independent assessment of evidenceCitation24. Presently, there are no published studies on budget impact analysis to guide healthcare funders, hospitals (public or private), and decision-makers on the budgetary impact of AVRs with BPAB and MV in Romania. To this end, we set out to analyze the budget impact of both valve types among AS patients aged over 65 years in Romania from the perspective of the public and private healthcare funders.

Methods

An international budget impact modelCitation25 was adopted for estimating the financial consequences of using a BPAB or a MV over a 5-year period in Romania, in line with guidelines set by the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) for Budget Impact Analysis (BIA)Citation26.

Model structure

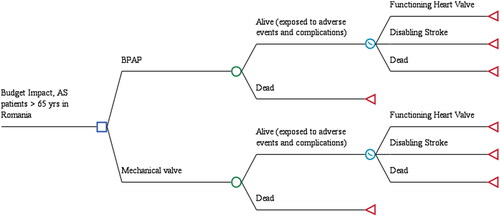

The decision-analytic model compared BPAB with MV in AS patients who are over 65 years old in Romania. The model includes two components: a decision tree structure that examines outcomes of both valve types in the first 30 days after implantation, and a partitioned survival model that analyzes the impact of long-term annual outcomes over a 5-year period (). The decision tree structure was used to capture early events that may occur within the first 30 days of the valve being inserted, capturing early adverse events and complications associated with each intervention, namely outcomes such as major bleeding, reoperations, minor thromboembolic events, endocarditis, disabling strokes, and death. The partitioned survival model includes health states for a functioning heart valve, disabling stroke, and death, and uses cycles of one month and probabilities of events to model how patients move between these states over 5 years. Partitioned survival analysis offers the advantage of accounting for time-varying transitions and capturing long-term complications, unlike Markov modeling, which assumes constant transitions between states.

Patient population and clinical outcomes

All AS patients eligible for the model were included at the time of AVR and were at risk for adverse events and complications during the first 30 days. These eligible patients were adults in Romania over 65 years of age who were expected to require their first surgery for AVRCitation27,Citation28. All surviving patients then entered the partitioned survival model in the functioning heart valve state until they experienced a disabling stroke or death. Those who have undergone surgery and experienced either no adverse effects or only temporary adverse events were in the health state of having a functional heart valve. The starting age for patients in the model was 65 years for both valve types (), consistent with published guidelinesCitation23.

Table 1. Patient population and clinical outcomes (Base Case Parameters).

Mortality

The decision tree captured the adverse events and complications associated with each intervention in the first 30 days following the procedure. The probability of death during the first 30 days following AVR models the immediate impact of the intervention on mortality. The model also includes the probability of death throughout the study period as a measure of the long-term impact of AVR on mortality, beyond the initial 30-day period. The survival curves for MV were calculated using parametric survival analysis of reconstructed Kaplan-Meir curvesCitation17, and assumed that the mortality rate was the same for patients with BPABCitation29. If the transition probabilities were below the average for the population, the survival curves were adjusted using mortality rates in Romania based on population life tablesCitation30.

The clinical outcomes for both valve types, including adverse events and complications, were obtained from published researchCitation17–20,Citation31,Citation32. This review involved a broad and comprehensive literature search, which identified relevant systematic reviews, meta-analyses, individual patient-level studies, and guidelines. The search was particularly focused on matched observational studies and study results for specific tissue valves that disaggregated results by age. A focused review of these studies was then conducted, extracting necessary data and employing various methods for data analysis, such as reconstructing data from published Kaplan-Meier survival curves. These clinical inputs, derived from a comprehensive and methodological review of the literature, were subsequently included in the decision-analytical model to inform the analysis.

Thromboembolic events and disabling stroke

Patients who have undergone implantation with either valve type, whether it be a BPAP or a MV, are at a significant risk of experiencing thromboembolic events, which can lead to disabling strokeCitation33–35. To account for this risk, transition probabilities were calculated by utilizing parametric survival analysis, which were derived from published clinical studies that have been conducted on patients diagnosed with ASCitation17–19. Notably, a large observational study that used propensity score matching techniques reported a hazard ratio (as seen in ) favored the use of BPAB over MV among patients who were over the age of 65Citation36. Together, the derived survival functions for thromboembolic events and the hazard ratio, determine the proportion of patients with BPAP and MV that remained event free. Furthermore, it was assumed that a specific and fixed proportion of thromboembolic events would lead to disabling stroke, this information was extracted from the patients who were diagnosed with AS and experienced permanent neurological deficitsCitation18.

Reoperation

Both valve types have been shown to be associated with a likelihood of reoperation, which can lead to an increased consumption of healthcare resourcesCitation37,Citation38. To thoroughly understand this, we analyzed reoperation rates that were obtained from a variety of published evidenceCitation18–20,Citation31,Citation39,Citation40, and then modeled the five-year budget impact that these rates would have. Notably, the reoperation rates were found to be higher among BPAB, especially during the first 30-day period post-operation and continued to be higher for all patients, as depicted in .

Major bleeding

Major bleeding events, such as acute hemorrhagic events that can occur in the reproductive, cerebral, gastrointestinal, cardiac, and respiratory vasculature, not only necessitate rehospitalization but also pose a risk of strokeCitation17,Citation20, thereby significantly contributing to the overall budget impact of both valve types. We integrated estimates from published evidence, where the definition of major bleeding events was carefully defined as suchCitation17. These events often require surgical exploration and can result in a longer hospital length of stay. Major bleeding rates were found to be lower among BPAB, specifically during the first 30-day period post-operation and continued to be lower for all patients as shown in .

Endocarditis

Infective endocarditis events, which are associated with lengthy antibiotic treatment, high mortality rates, and the possibility of reoperation, are another important factor to consider when comparing both types of valvesCitation18,Citation19,Citation32,Citation41,Citation42. To thoroughly assess this issue, we compared endocarditis rates during the first 30-day period post-operation and for the entire duration of our model. Both valve types were associated with similar event rates (as seen in ) during the initial 30-day period and an estimated annual rate of 0.3%–1.2%Citation32. As a result, for the duration of our model, we used the midpoint of this annual rate (as seen in ) as an approximation.

Anticoagulation complications

MV implantation is associated with lifetime anticoagulation therapy, which in turn increases the risk of anticoagulation-related complications, such as major bleeding and thromboembolic eventsCitation17,Citation22,Citation23,Citation39,Citation43. To accurately evaluate this impact, we examined estimates from published evidence and took into account the potential costs associated with re-admission and treatment for patients with subtherapeutic International Normalized Ratio (INR), INR monitoring and adjustments in anticoagulation dosageCitation22. The risk of anticoagulation complications was linked to only MV estimated up to six weeks post-procedure for readmission and additional monitoring (as seen in ). The anticoagulation complication at six weeks is a one-time cost. However, in the long term, the modeling of major bleeding is directly related to the anticoagulation treatment rather than the valves itself.

Pacemaker implantation

Although there is a limited amount of data available on the prevalence of new permanent pacemaker implantation among AS patients who have received either valve type, data that is currently on file suggests that 5.3% of patients receive a pacemaker applicable to both BPAB and MVCitation39. Given that the event rates and costs associated with pacemaker implantation appear to be the same for both types of valves, we excluded the impact of new permanent pacemaker implantation from our analysis since it would be considered budget neutral.

Costs and resource consumption

Costs on resource consumption were obtained from a retrospective analysis of an administrative database from a public hospital, Emergency Institute for Cardiovascular Diseases “Prof. Dr. C.C. Iliescu”, Bucharest, Romania. We chose to analyze costs rather than use DRG tariffs in Romania because the latter do not provide a disaggregated view of cost inputs required for modeling, and AVR with either BPAB or MV map to the same DRG code, limiting the practical use of DRG tariffs in the budget impact analysis. To this end, we included patients in the analysis which had a diagnosis of severe AS, underwent AVR from January to December 2019 and were discharged to home or transferred to another healthcare facility. The exclusion criteria were: preprocedural diagnosis of infectious endocarditis, urgent procedure, and additional planned or emergent procedure (mitral valve repair/replacement, tricuspid valve repair/replacement, myocardial revascularization, ascending aorta replacement, etc.). The final cohort included 114 consecutive patients, 57 patients with a mechanical prosthesis and 57 patients with a biological prosthesis, representing 82.1% out of all patients that underwent isolated AVR irrespective of initial diagnosis (infectious endocarditis) or emergency status. The chosen time interval, January to December 2019, reflects cost estimations before the COVID-19 pandemic, which imposed additional direct and indirect costs (testing, protection equipment, longer hospital stays, and lower number of procedures due to restrictions).

Only direct medical costs are modeled from the perspective of government and private institutions in Romania in 2022 Euros (EUR). To accurately account for the costs, both valve types were separated into distinct in-hospital phases for resource consumption - procedural and postprocedural. In the outpatient setting, various complications and their related long-term costs were also considered such as endocarditis, major bleeding, disabling stroke, and minor thromboembolic event. Other recurring resource consumption linked to continuous monitoring of the implanted heart valve, such as frequent clinic visits, laboratory tests, were also considered in the outpatient setting. The costs were quantified and represented in a structured manner, to accurately account for different frequencies of resource consumption. The structured costs provide a detailed representation of resource consumption per procedure, per event, or per day; for instance, in-hospital stays were calculated per procedure, while costs in the outpatient setting were calculated per event or per day (as seen in ) and may include an in-hospital stay for major bleeding, endocarditis, or major stroke. The remaining cost elements associated with recurring resource consumption, such as anticoagulation therapy, were calculated per annum.

Table 2. Costs (in EUR) (Base Case Parameters).

In-Hospital procedure costs

In-hospital stays were carefully analyzed and divided into two distinct phases, procedural and postprocedural. These phases cover a wide range of costs associated with the treatment, including the fees of consultants, the cost of laboratory tests, the cost of the BPAB or the MV, the duration of the procedure, the utilization of human resources, the length of the stay in the hospital, and the costs of any necessary drugs (as presented in ). To ensure accurate cost estimates, input data from two different institutions (public and private) in Romania that perform AVR procedures were gathered and analyzed. Inputs were then compared, and any outliers were removed using Tukey fences, which sets upper and lower limits at 1.5 times the interquartile rangeCitation44,Citation45. This approach resulted in the elimination of potential errors in cost input estimates or any noticeably higher or lower cost estimates due to a single institution in either the public or private sector. The procedure cost per patient included the cost of BPAB and the average cost of MV in Romania. The calculated mean of the remaining institutional cost inputs were included in the base case analysis and used to estimate the costs of both valve types.

The use of human resources per surgical procedure was calculated based on an average surgery time of 146 minCitation46 which was corroborated by expert opinion. The human resource utilization includes all the personnel required for an AVR procedure, such as a cardiac surgeon, anesthesiologist, surgical assistant, perfusionist, nursing staff, and operating department practitioner. We assumed that human resources are the same for procedures that involve a BPAB and a MV, for purposes of simplicity.

Outpatient complication costs

The 5-year complication costs are modeled, particularly those that may occur after a patient is discharged from the hospital. However, determining the budget impact of BPAB versus MV can be challenging in Romania, due to the lack of itemized data on the cost of healthcare interventions. To account for this, we identified the main cost elements such as length of stay, consultations, medication, duration of surgery, and laboratory tests and estimated the total resource use for major bleeding and endocarditis, per event. Additionally, we also calculated the recurring cost of a disabling stroke using purchasing power parity (PPP) adjustments to cost inputs specific to the United Kingdom and RomaniaCitation47.

AS patients with a BPAB or a MV typically require an annual echocardiogram after implantation, which is in line with the expert opinion in Romania and the ESC/EACTS Guidelines. It is worth noting that both valve types require anticoagulation treatment, however, the treatment duration is different, as it is required only for 3 months postprocedural for the BPAB and for the duration of the budget impact model for the MVCitation48. The general practitioner visits to monitor INR levels and the lowest priced acenocumarol 4 mg (pack of 20s – EUR 2.40) was taken into account for 3 months in BPAP and MV and also long-term for MV onlyCitation49. For added validity, we compared the calculated costs per event to published evidence on costs reported in published cost-effectiveness analyses in RomaniaCitation50,Citation51. Budget impact results were calculated based on an eligible population defined by available data on AS patients above 65 years of age in Romania who are first-time AVR candidatesCitation28,Citation52,Citation53. The conservative uptake of BPAB was assumed to start at 5.1% (Year 1) and increase to 8.1% (Year 5), based on available market growth estimatesCitation54. The cost inputs remained undiscounted to align with ISPOR guidelines for BIACitation26.

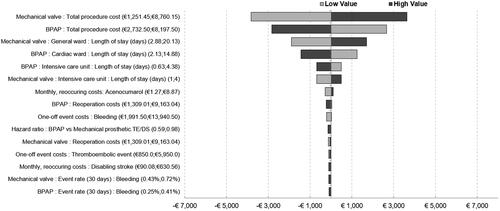

Sensitivity analysis

One-way sensitivity analysis (OWSA) was conducted with 50% lower and upper values of cost estimates to account for the variation between the facilities where AVR procedures are performed. These OWSA results were presented in a tornado diagram to facilitate easy comparison across all input categories. To account for patient-level variability, we also applied 50% lower and upper values to adjust the inputs for the length of stay. We varied the values within 25% of the base case for all other inputs, including complication event rates.

Results

The overall budget impact results, which include the incremental budget impact and the results for the initial procedure cost, are available in . We present results for the initial 30-day period and annually thereafter to align with the annual budgeting period of the budget holder in Romania.

Table 3. Budget impact results (in 2022 EUR) by year.

Overall, the budget impact of BPAB versus MV approaches budget neutrality and the incremental savings gradually increase each year as more AS patients are implanted with BPAB. Although the initial procedure and reoperation are more expensive with BPAB, these costs are offset by savings in all other cost categories, notably savings in acenocumarol use, which is only applicable to MV and BPAP during the first 3 months post-procedure, and reduced rates of anticoagulation complications, major bleeding, minor thromboembolic events, and disabling strokes. The cost per initial procedure per patient is 460 EUR higher for BPAB compared to mechanical valves. This is due to the higher device costs included in the procedural costs for BPAB, however, a portion of this cost is offset by savings owing to the shorter hospital length of stay included in the postprocedural costs. The per-patient cost of the initial procedure remained constant in the model, year-on-year.

Sensitivity analysis

As seen in the results of the OWSA (), the overall budget impact results are largely driven by the total procedure costs, including hospital length of stay, for both valve types. The hazard ratio for thromboembolic events did not have a large impact as most patients remained event free based on the survival functions derived from published evidenceCitation36. The model suggests that as the total procedure costs for BPAB decline, greater budget savings are achieved. The costs for anticoagulation treatment, when higher for MV, results in greater budget savings for BPAB.

Discussion

The use of BPAB in AS patients over 65 years old in Romania is budget neutral and results in savings, year-on-year, as more patients are implanted. Savings in acenocumarol, major bleeding, minor thromboembolic events, disabling strokes, and anticoagulation complications offset the higher, initial procedure cost and reoperations.

These findings are comparable to a recently published budget impact analysis in Saudi Arabia on the financial outcomes of bioprosthetic valves with RESILIA tissue versus mechanical valves, also among patients older than 65 yearsCitation25. The bioprosthetic valve with RESILIA tissue is an improvement on the BPAB for AVR. It prevents calcification by blocking residual aldehyde groups from binding to calcium, thus leading to reductions in structural valve deterioration and improvements in hemodynamic performanceCitation25. Bioprosthetic valves with RESILIA tissue in Saudi Arabia resulted in budget savings from the first year reflecting improvements in clinical outcomes, notably reductions in re-operation rates reported in the COMMENCE trialCitation39.

Differences in healthcare system structures and cost inputs between Romania and Saudi Arabia limit the direct comparability of results. Saudi Arabia’s healthcare system is a multiple-payer system with considerable variability in AVR costs, while Romania’s is predominantly a public healthcare system with AVR costs covered by DRG schedules. In Romania, the ratio of the daily ICU rate to a cardiac surgeon consultation is 4.5, lower than the same ratio of 15.8 in Saudi Arabia. Structural differences in healthcare markets and the relative contribution of cost inputs highlight that results between countries are not easily compared.

A study that adopted a United States (US) payer perspective reported the long-term financial outcomes of tissue and MV and found that tissue valves were budget efficient, resulting in savings of up to USD 16,008 for patients over 65 years old. Calculations were based on evidence for the Carpentier-Edwards Perimount aortic valveCitation18,Citation19, and not the bioprosthetic valves with RESILIA tissueCitation39. As with the results above for Romania, the study found that savings offset the costs of reoperation. The US study did not include disabling strokes but factored in patient costs which limits a direct comparison with the results in Romania. The US study’s findings were consistent with those reported in the Saudi Arabia research, showing cost savings starting from year 1 and gradually increasing to year 5. Similarly, these comparisons highlight the structural differences in healthcare markets and the relative contribution of cost inputs. The same BPAB were budget-saving in the US from year 1 and were budget neutral in the present study.

Input costs in Romania are overall lower compared to other European countries based on expert opinion, which translates to overall lower event-related costs. We searched all published cost-effectiveness analyses in Romania to compare event costs and only two reported disaggregated input costs. Liviu et al. reported payments for hospitalization with a surgical intervention among metastatic renal carcinoma patients of 520 eurosCitation50, lower compared to the hospitalization events in our study, while costs for radiography and echography were comparable. Sava et al. reported higher human resource costs (per minute) which may reflect differences in income levels of psychiatrists versus cardiac surgeons in RomaniaCitation51. Overall, human resource costs were not the major driver of results in the present study.

Partitioned survival analysis was chosen as the method for this study due to its ability to account for the time-varying nature of probabilitiesCitation55 and to capture long-term complications associated with aortic stenosis and aortic valve replacement. Unlike traditional Markov frameworks that assume constant transitions, the partitioned survival model used in this study allowed for the extrapolation of long-term survival data, considering how the probabilities of mortality and disabling strokes would evolve over time. This approach was deemed appropriate based on published budget impact models which also considered longer-term outcomesCitation56–59. By employing partitioned survival analysis, the study also aimed to capture the key differences between the valves in terms of re-operations and anticoagulant medication costs, factors that are likely to impact patient outcomes and resource utilization.

The findings of this study have important implications for patients, policymakers, and healthcare professionals in Romania. Despite the higher reoperation rates, BPAB may be a clinically efficient option for AS patients over 65 due to a reduction in acenocumarol use, major bleeding, minor thromboembolic events, debilitating strokes, and anticoagulation problems. To account for the difference between institutions that perform AVR procedures, a OWSA was performed with 50% lower and upper values of cost estimations. These results may help policymakers in Romania decide if BPAB is a preferred alternative to MV. To this end, policymakers may wish to consider variability around the total procedure costs for both valve types when setting annual budgets as these have a significant impact on the overall expenses. Direct comparisons of the present results are constrained by differences in healthcare system structures and cost inputs between Romania and other countries, highlighting the need for additional Romania-specific economic evaluations to complement decision criteria on AS clinical practice and healthcare policy more broadly.

Limitations

To the author's knowledge, this is not only the first budget impact analysis of its kind in Romania, but also the first to cost AVR procedures in Romania for the purposes of a BIA. The reimbursement of AVR procedures is based on a Diagnosis-Related Group (DRG) system designed to change the way hospitals are financed and to improve the effectiveness, quality, and efficiency of care in Romania. The DRG system began with a USAID funded project in 1999-2001 and has since expanded to involve various stakeholders including hospitals, the MoH, the NHIH, the Directorates of Public Health, the National Institute for Research - Development in Health and the Computing Center and Health StatisticsCitation60. The current DRG system groups patients with similar diagnoses and similar hospital services required, based on disease and intervention codes, as well as other routine variables such as age, sex, length of stay, and same-day status. This system is used to relate the number and type of patients treated in admitted acute episodes of care to the resources required for their treatmentCitation61.

The DRG system uses tariffs with limited practical use in BIA. The AVR procedure tariff calculates the average cost of treating patients based on resources required to replace the aortic valve, which may vary year-on-year, due to factors such as productivity, patient composition, and cost estimation methods. Given the lack of disaggregated cost inputs used in calculating a DRG tariff for AVR procedures in Romania, our research estimated resource use for the individual cost components of the procedural and postprocedural phases. We only included the main components, consumables and capital equipment that are routinely used during these phases were excluded, similarly in ICU and the general ward. Consumables and capital equipment are not resource intensive for either BPAB or MV, however, inclusion of these in future research may improve the accuracy of the budget impact results.

Partitioned survival analysis is associated with several limitations that can potentially impact its accuracy. Primarily, partitioned survival analysis operates under the assumption that the survival functions it models are independent, an assumption that may not hold in real-world scenarios. For instance, in situations where mortality rates differ between BPAB and MV patients, this model’s inability to accommodate such variations could lead to inaccuracies. Further, these models struggle to handle complex dependencies, particularly when projecting beyond the known data period the varying risks of thromboembolic events and disabling strokes among different patients. The model relies on published research data and observational studies, which when extrapolated, might not accurately reflect long-term trends and could introduce biases. Notwithstanding these limitations, we decided to model the budget impact of BPAB and MV over a five-year period to alleviate the long-term limitations associated with partitioned survival analysis, especially in cost-effectiveness analyses.

Outpatient complications (major bleeding, endocarditis, minor thromboembolic events, and disabling stroke) were costed based on the reimbursements provided to the hospital under the above DRG system. The reimbursements recorded per patient in the data we analyzed may underestimate, based on expert opinion, the true cost of treating an outpatient complication. For example, we estimated the cost of endocarditis in the 30-day post-procedure period was 8,883 Euros, but in reality, this may be higher with long-duration antibiotic use and extensions in the length of stay due to additional surgery. Similarly, future, monthly costs of supporting patients with a disabling stroke were estimated with PPP adjustments given the lack of data in the outpatient setting. We recommend that future researchers consider a micro-costing analysisCitation62 or time-dependent activity costingCitation63 of outpatient complications as these will improve the accuracy of results reported herein and may favor either BPAB or MV.

In this study, due to commercial and confidential reasons, it was not feasible to record the individual prices of BPAP and MV. The procedure cost presented in encompasses the cost of the valve, procedure-related human resources such as cardiology and cardiac surgery, as well as the expenses associated with tests including echocardiogram, chest X-Ray, CT coronary angiogram, and lung function tests for both BPAP and MV. The primary focus of this study is to provide valuable insights into the broader economic impact, resource consumption, and long-term implications associated with valve cost, human resources, and procedure-related tests. Through the analysis of these factors and the assessment of outcomes, our study contributes to a comprehensive understanding of the economic implications of these valves. Nevertheless, we acknowledge that a limitation of this approach is the lack of a disaggregated view of the cost components within the procedure cost, including the specific valve cost. To address this limitation, future research could explore a more detailed breakdown of the cost components within the DRG tariffs for AVR. The publication of public procurement prices for AVR technologies and the adoption of micro-costing analysis or time-dependent activity costing methods, as previously discussed, could provide further insights into the cost structure.

In our sensitivity analysis, we applied broad upper and lower values to estimate their impact on overall results, however these may still include parameter uncertainty due to limited data availability. For example, the costs for the first 30-day post-procedure period and outpatient complications may underestimate the actual cost of AVR procedures for the reasons discussed above. Additionally, while our study primarily focused on patients over 65 years, data from younger patient cohorts were used when event rates were unavailable. For example, Glaser et al. reported a mean age of 59.9 years for MVCitation15, and Lopez-Marco et al. a mean age of 54.6 years for MVCitation23. Event rates among younger patients may therefore favor the budget impact for MV in the above results. Future research is needed on the budget impact of BPAB vs. MV among patients 55-64 years old in Romania.

Financial outcomes are presented over a five-year horizon, but we’re uncertain if the durability of BPAB due to structural valve deterioration (SVD) and higher reoperation rates will persist beyond this time frame. In the future, AS patients may be increasingly implanted with a bioprosthetic valve with RESILIA tissue, an improvement on the BPAB. Additional clinical evidence may also emerge from the RESILIENCE trial focused on reoperations or deaths related to SVD among patients under 65 years old at 7, 9, and 11 yearsCitation60.

Results presented above should therefore be interpreted within the scope of limitations outlined above: i) aggregated versus disaggregated cost inputs, ii) consumables and capital equipment used in AVR procedures, iii) micro-costing of outpatient complications, iv) age-related variations of event rates, and v) valve durability.

Conclusion

Our study shows that adopting BPAB as a treatment option for AS patients in Romania can lead to cost savings and long-term economic benefits. By mitigating procedure costs and increasing anticoagulation treatment costs, BPAB offers a budget-neutral option that can help healthcare providers, policymakers, and patients alike manage the growing burden of AS in Romania.

Transparency

Declaration of financial/other interests

JLC is a consultant for Edwards Lifesciences. VAI, LD, ATS, and CP are supported by their employing institutions. JD, AW, and AS are employees at Edwards Lifesciences.

Author contributions

JLC, AS, JD, AW: Study concept and design.

JLC, VAI, LD, ATS, CP, JD, AW, and AS: Data collection and data interpretation.

JLC primarily wrote the manuscript along with VAI, LD, and CP.

JLC, VAI, LD, ATS, CP, JD, and AW revised the manuscript.

Reviewer disclosures statement

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the contribution of Belén Martí-Sánchez, Edwards Lifesciences, and her role in the initial study conceptualization and design.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Radulescu C-I, Deleanu D, Chioncel O. Survival, functional capacity and quality of life after transcatheter aortic valve implantation: present considerations and future perspectives. Rom J Cardiol. 2021;31(2):319–325. doi: 10.47803/rjc.2021.31.2.319.

- Thoenes M, Bramlage P, Zamorano P, et al. Patient screening for early detection of aortic stenosis (as)-review of current practice and future perspectives. J Thorac Dis. 2018;10(9):5584–5594. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2018.09.02.

- Eugène M, Duchnowski P, Prendergast B, et al. Contemporary management of severe symptomatic aortic stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;78(22):2131–2143. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.09.864.

- Nkomo VT, Gardin JM, Skelton TN, et al. Burden of valvular heart diseases: a population-based study. Lancet. 2006;368(9540):1005–1011. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69208-8.

- Durko AP, Osnabrugge RL, Van Mieghem NM, et al. Annual number of candidates for transcatheter aortic valve implantation per country: current estimates and future projections. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(28):2635–2642. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy107.

- Eveborn GW, Schirmer H, Heggelund G, et al. The evolving epidemiology of valvular aortic stenosis. the tromso study. Heart. 2013;99(6):396–400. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2012-302265.

- Iung B, Baron G, Butchart EG, et al. A prospective survey of patients with valvular heart disease in Europe: the Euro heart survey on valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2003;24(13):1231–1243. doi: 10.1016/s0195-668x(03)00201-x.

- Osnabrugge RLJ, Mylotte D, Head SJ, et al. Aortic stenosis in the elderly: disease prevalence and number of candidates for transcatheter aortic valve replacement: a meta-analysis and modeling study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(11):1002–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.015.

- Hartley A, Hammond-Haley M, Marshall DC, et al. Trends in mortality from aortic stenosis in Europe: 2000–2017. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8:748137. [Internet]. Available from: doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2021.748137.

- Iung B, Delgado V, Rosenhek R, et al. Contemporary presentation and management of valvular heart disease: the EURObservational research programme valvular heart disease II survey. Circulation. 2019;140(14):1156–1169. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.041080.

- OECD. Romania: country health profile 2021. [Internet]. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; 2021 cited 2023 Jan 23]. Available from: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/romania-country-health-profile-2021_74ad9999-en.

- World Health Organization. Can people afford to pay for health care? New evidence on financial protection in Romania [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2023 Jan 23]. Available from: https://www.who.int/europe/publications/i/item/9789289057905.

- Casa Naţională de Asigurări de Sănătate. Programul national de boli cardiovasculare. [Internet]. Casa Naţională de Asigurări de Sănătate. 2023 [cited 2023 Jan 18]. Available from: http://www.casan.ro/page/programul-national-de-boli-cardiovasculare.html.

- Degenhard J. Health expenditure GDP share in Romania 2028 [Internet]. Statista. 2023 cited 2023 Jan 15]. Available from: https://www.statista.com/forecasts/1141639/health-expenditure-gdp-share-forecast-in-romania.

- ESC guides – the abbreviated version. [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2023 Jan 23]. Available from: https://www.cardioportal.ro/ghiduri-src/ghidurile-esc-varianta-prescurtata/.

- Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American college of cardiology/American heart association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021;143(5):e72–e227. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000923.

- Glaser N, Jackson V, Holzmann MJ, et al. Aortic valve replacement with mechanical vs. biological prostheses in patients aged 50–69 years. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(34):2658–2667. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv580.

- Bourguignon T, Bouquiaux-Stablo A-L, Candolfi P, et al. Very long-term outcomes of the Carpentier-Edwards perimount valve in aortic position. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;99(3):831–837. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.09.030.

- Bourguignon T, Lhommet P, El Khoury R, et al. Very long-term outcomes of the Carpentier-Edwards perimount aortic valve in patients aged 50–65 years. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2016;49(5):1462–1468. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezv384.

- Brennan JM, Edwards FH, Zhao Y, et al. Long-term safety and effectiveness of mechanical versus biologic aortic valve prostheses in older patients: results from the society of thoracic surgeons adult cardiac surgery national database. Circulation. 2013;127(16):1647–1655. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.002003.

- Puskas JD, Bavaria JE, Svensson LG, et al. The COMMENCE trial: 2-year outcomes with an aortic bioprosthesis with RESILIA tissue. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2017;52(3):432–439. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezx158.

- Lopez-Marco A, Grant SW, Mohamed S, et al. Impact of mechanical aortic prostheses in hospital stay and anticoagulation related complications. J Surg Res. 2021;04(02):187–196. doi: 10.26502/jsr.10020125.

- Vahanian A, Beyersdorf F, Praz F, et al. 2021 ESC/EACTS guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(7):561–632. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab395.

- Gabriela SS, M C, C V. To what extent is Romania prepared to join health technology assessment cooperation at European level. The Medical-Surgical Journal. 2021;125:146–153.

- Carapinha JL, Al-Omar HA, Aluthman U, et al. Budget impact analysis of a bioprosthetic valve with a novel tissue versus mechanical aortic valve replacement in patients older than 65 years with aortic stenosis in Saudi Arabia. J Med Econ. 2022;25(1):1149–1157. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2022.2133320.

- Mauskopf JA, Sullivan SD, Annemans L, et al. Principles of good practice for budget impact analysis: report of the ISPOR task force on good research practices–budget impact analysis. Value Health. 2007;10(5):336–347. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00187.x.

- The World Bank. Population, total - Romania. | Data [Internet]. [cited 2023 Jan 30]. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL?locations=RO.

- US Census Bureau. Census Bureau Releases New Population Projections for 30 Countries and Areas. [Internet]. Census.gov. [cited 2023 Jan 30]. Available from: https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2021/population-projections-international-data-base.html.

- Attia T, Yang Y, Svensson LG, et al. Similar long-term survival after isolated bioprosthetic versus mechanical aortic valve replacement: a propensity-matched analysis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2022;164(5):1444–1455.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2020.11.181.

- World Health Organization. Global Health Observatory, Life tables [Internet]. WHO. World Health Organization; [cited 2021 Sep 21]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/gho/data/view.main.61440?lang=en.

- Zhao DF, Seco M, Wu JJ, et al. Mechanical versus bioprosthetic aortic valve replacement in middle-aged adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;102(1):315–327. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.10.092.

- Habib G, Lancellotti P, Antunes MJ, et al. ESC guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis: the task force for the management of infective endocarditis of the european society of cardiology (ESC). endorsed by: European association for cardio-thoracic surgery (EACTS), the European association of nuclear medicine (EANM). Eur Heart J. 2015;36(44):3075–3128. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv319.

- Vahanian A, Alfieri O, Andreotti F, et al. Guidelines on the management of valvular heart disease (version 2012). Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2451–2496.

- Leiria TLL, Lopes RD, Williams JB, et al. Antithrombotic therapies in patients with prosthetic heart valves: guidelines translated for the clinician. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2011;31(4):514–522. doi: 10.1007/s11239-011-0574-9.

- Sanaani A, Yandrapalli S, Harburger JM. Antithrombotic management of patients with prosthetic heart valves. Cardiol Rev. 2018;26(4):177–186. doi: 10.1097/CRD.0000000000000189.

- Kytö V, Ahtela E, Sipilä J, et al. Mechanical versus biological valve prosthesis for surgical aortic valve replacement in patients with infective endocarditis. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2019;29(3):386–392. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivz122.

- Head SJ, Çelik M, Kappetein AP. Mechanical versus bioprosthetic aortic valve replacement. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(28):2183–2191. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx141.

- Diaz R, Hernandez-Vaquero D, Alvarez-Cabo R, et al. Long-term outcomes of mechanical versus biological aortic valve prosthesis: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2019;158(3):706–714.e18. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2018.10.146.

- Bavaria JE, Griffith B, Heimansohn DA, et al. Five-year outcomes of the COMMENCE trial investigating aortic valve replacement with RESILIA tissue. Ann Thorac Surg. 2023;115(6):1429–1436. S0003-4975(22)00063-7.

- Etnel JRG, Huygens SA, Grashuis P, et al. Bioprosthetic aortic valve replacement in nonelderly adults: a systematic review, meta-analysis, microsimulation. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2019;12(2):e005481. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.118.005481.

- Tackling G, Lala V. Endocarditis Antibiotic Regimens. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing;2022cited 2022 Jun 24]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK542162/.

- Baddour LM, Wilson WR, Bayer AS, et al. Infective endocarditis in adults: diagnosis, antimicrobial therapy, and management of complications. Circulation. 2015;132(15):1435–1486. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000296.

- Bartus K, Litwinowicz R, Bilewska A, et al. Final 5-year outcomes following aortic valve replacement with a RESILIATM tissue bioprosthesis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2021;59(2):434–441. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezaa311.

- Tukey JW. Exploratory data analysis. [Internet]. Reading, Mass. Addison-Wesley Pub. Co.; 1977 cited 2022 Sep 12]. Available from: http://archive.org/details/exploratorydataa00tuke_0.

- InterQuartile Range (IQR). [Internet]. [cited 2022 Sep 12]. Available from: https://sphweb.bumc.bu.edu/otlt/MPH-Modules/BS/BS704_SummarizingData/BS704_SummarizingData7.html.

- Wilbring M, Tugtekin S-M, Alexiou K, et al. Transapical transcatheter aortic valve implantation vs conventional aortic valve replacement in high-risk patients with previous cardiac surgery: a propensity-score analysis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2013;44(1):42–47. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezs680.

- International Comparison Program (ICP). [Internet]. World Bank. [cited 2022 Jul 14]. Available from: https://www.worldbank.org/en/programs/icp.

- Keeling D, Baglin T, Tait C, et al. Guidelines on oral anticoagulation with warfarin – fourth edition. Br J Haematol. 2011;154(3):311–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08753.x.

- Ministry of Health Romania. Maximum Prices of Human Use Drugs. Ordin Nr. 44. din 23 februarie 2022 [Internet]. Ministry of Health; 2022. Available from: https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocument/251961.

- Liviu Preda A, Galieta Mincă D. Cost-effectiveness analysis of treatment for metastatic renal carcinoma in Romania. J Med Life. 2018;11(4):306–311. doi: 10.25122/jml-2018-0069.

- Sava FA, Yates BT, Lupu V, et al. Cost-effectiveness and cost-utility of cognitive therapy, rational emotive behavioral therapy, and fluoxetine (prozac) in treating depression: a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Psychol. 2009;65(1):36–52. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20550.

- Baghai M, Wendler O, Grant SW, et al. Aortic valve surgery in the UK, trends in activity and outcomes from a 15-year complete national series. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2021;60(6):1353–1357. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezab199.

- Andell P, Li X, Martinsson A, et al. Epidemiology of valvular heart disease in a swedish nationwide hospital-based register study. Heart. 2017;103(21):1696–1703. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2016-310894.

- Edwards Lifesciences. Data on hand: unpublished raw data. Nyon, Switzerland: Edwards Lifesciences; 2023.

- Woods B, Sideris E, Palmer S, et al. NICE DSU Technical Support Document 19. Partitioned Survival Analysis for Decision Modelling in Health Care: A Critical Review. [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2023 May 11]. Available from: https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/nice-dsu/tsds/partitioned-survival-analysis.

- Wang XJ, Wang Y-H, Ong MJC, et al. Cost-Effectiveness and budget impact analyses of tisagenlecleucel in pediatric and young adult patients with relapsed or refractory B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia from the Singapore healthcare system perspective. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2022;14:333–355. doi: 10.2147/CEOR.S355557.

- Wang XJ, Wang Y-H, Li SCT, et al. Cost-effectiveness and budget impact analyses of tisagenlecleucel in adult patients with relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma from singapore’s private insurance payer’s perspective. J Med Econ. 2021;24(1):637–653. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2021.1922066.

- Skalt D, Moertl B, von Bergwelt-Baildon M, et al. Budget impact analysis of CAR T-cell therapy for adult patients with relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in Germany. Hemasphere. 2022;6(7):e736. doi: 10.1097/HS9.0000000000000736.

- Basic E, Kappel M, Misra A, et al. Budget impact analysis of the use of oral and intravenous therapy regimens for the treatment of relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma in Germany. Eur J Health Econ. 2020;21(9):1351–1361. doi: 10.1007/s10198-020-01219-3.

- CRUEASS. DRG Romania - Center for Research and Evaluation of Health Services. [Internet]. What is the DRG system. 2023 [cited 2023 Jan 17]. Available from: https://www.drg.ro/index.php?p=drg&s=romania.

- IHACPA. AR-DRGs [Internet]. 2023 cited 2023 Jan 17]. Available from: https://www.ihacpa.gov.au/health-care/classification/admitted-acute-care/ar-drgs.

- Potter S, Davies C, Davies G, et al. The use of micro-costing in economic analyses of surgical interventions: a systematic review. Health Econ Rev. 2020;10(1):3. doi: 10.1186/s13561-020-0260-8.

- Bobade RA, Helmers RA, Jaeger TM, et al. Time-driven activity-based cost analysis for outpatient anticoagulation therapy: direct costs in a primary care setting with optimal performance. J Med Econ. 2019;22(5):471–477. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2019.1582058.