Abstract

Background

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a leading cause of chronic pain and disability. Prior studies have documented racial disparities in the clinical management of OA. The objective of this study was to assess the racial variations in the economic burden of osteoarthritis within the Medicaid population.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective observational study using the MarketScan Multi-State Medicaid database (2012-2019). Newly diagnosed, adult, knee and/or hip OA patients were identified and followed for 24 months. Demographic and clinical characteristics were collected at baseline; outcomes, including OA treatments and healthcare resource use (HCRU) and expenditures, were assessed during the 24-month follow-up. We compared baseline patient characteristics, use of OA treatments, and HCRU and costs in OA patients by race (White vs. Black; White vs. Other) and evaluated racial differences in healthcare costs while controlling for underlying differences. The multivariable models controlled for age, sex, population density, health plan type, presence of non-knee/hip OA, cardiovascular disease, low back pain, musculoskeletal pain, presence of moderate to severe OA, and any pre-diagnosis costs.

Results

The cohort was 56.7% White, 39.9% Black and 3.4% of Other race (American Indian/Alaska Native, Hispanic, Asian, Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander, two or more races and other). Most patients (93.8%) had pharmacologic treatment for OA. Inpatient admission during the 24-month follow-up period was lowest among Black patients (25.8%, p < .001 White vs. Black). In multivariable-adjusted models, mean all-cause expenditures were significantly higher in Black patients ($25,974) compared to White patients ($22,913, p < .001). There were no significant differences between White patients and patients of Other race ($22,352).

Conclusions

The higher expenditures among Black patients were despite a lower rate of inpatient admission in Black patients and comparable length and number of hospitalizations in Black and White patients, suggesting that other unmeasured factors may be driving the increased costs among Black OA patients.

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY

Higher healthcare costs were observed in Black Medicaid patients with knee/hip osteoarthritis despite lower rates of inpatient admission. We observed these differences in this Medicaid population, where socioeconomic status is more homogeneous.

Black patients had significantly higher healthcare costs compared to White patients and the difference persisted even after accounting for underlying differences in Black and White patients.

Higher healthcare costs among Black patients were found in both the baseline and follow-up periods overall for all types of healthcare (hospitalizations, ER, office visit, other services).

Higher hospitalization costs in Black patients were observed despite lower rates of hospitalizations in Black patients. These increased costs cannot be attributed to either longer or more frequent hospitalizations; no significant difference in either the length of stay or the number of hospitalizations was observed when comparing Black patients to White patients.

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a chronic, degenerative joint disease highly prevalent in middle-aged and elderly adults, characterized by joint pain and stiffness, swelling at the joint, and decreased range of motionCitation1. These symptoms can vary from person to person stressing the need for personalized treatment approachesCitation2. OA affects approximately 1 in 7 adults in the U.SCitation1. and is associated with significant clinical and economic costsCitation3. Treatment for OA is aimed at controlling pain and maintaining quality of life using non-pharmacologic and pharmacologic interventionsCitation4. Pharmacologic options are available to treat patients with OA who do not experience adequate pain control with non-pharmacologic modalitiesCitation4,Citation5.

Analgesics (such as acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs], duloxetine and opioids [including tramadol]) and intra-articular therapies (corticosteroids and viscosupplements such as hyaluronic acid) could be ineffective over time or unsuitable for some patientsCitation4,Citation6–9. Patients commonly switch and augment treatments using multiple classes of medications, or seek surgical interventions to achieve satisfactory pain managementCitation10, highlighting an unmet need for pain management in patients with OACitation5,Citation11.

Because of the long-term, progressive nature of osteoarthritis, patients with OA tend to have higher health care resource use (HCRU) and costs compared to those without OACitation9,Citation12. Prior studies have shown that healthcare costs in patients with OA can be more than twice those of patients without OACitation13. As OA pain worsens, it tends to be associated with increased rates of comorbidities, such as obesity and depressionCitation14, which could further impact HCRU and costs. Studies on clinical care, pain management and treatment of OA have documented variation by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status, with less optimal pain management and clinical outcomes in racial minorities, compared to non-Hispanic White patientsCitation15–18. Prior studies have also documented the marked underutilization of total joint replacement by racial minoritiesCitation19–21. An 18-year analysis of Medicare data found evidence of persistent racial disparities in joint arthroplasty usage and surgical outcomesCitation21. Given these variations in clinical care and management, it is likely that the economic burden of OA may also vary by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status.

Recent studies on healthcare utilization and expenditures in patients with OA using administrative claims databases have reported higher utilization and expenditures in patients with OA compared to non-OA controlsCitation22,Citation23. However, these studies focused on commercially insured patients with OA and did not examine healthcare utilization patterns or cost by race/ethnicity. A prior U.S. study evaluated racial variation in healthcare costs, but these costs were not specific to OA-patientsCitation24. The objective of this study was to characterize the racial variation in HCRU and direct healthcare costs among those with knee and/or hip OA in a population of knee/hip patients with OA with Medicaid. This study identified discrepancies in patterns of healthcare resource use and direct healthcare costs by race in a Medicaid population where socioeconomic status is more homogenous, extending prior research.

Methods

Study design and data source

This retrospective, observational cohort study used data from the MarketScan Multi-State Medicaid Database from 1 January 2012, to 31 December 2019. The Multi-State Medicaid database includes geographically dispersed U.S states and includes records of inpatient services, inpatient admission, outpatient services, prescription drug claims, as well as information on long-term care and other medical care. Data included in the MarketScan Multi-State Medicaid Database are provided directly to Merative from state Medicaid programs. All data records are de-identified and fully compliant with U.S. patient confidentiality requirements, including the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996. Because the study used only de-identified patient records and did not involve the collection, use, or transmittal of individually identifiable data, Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was not necessary.

Patient selection

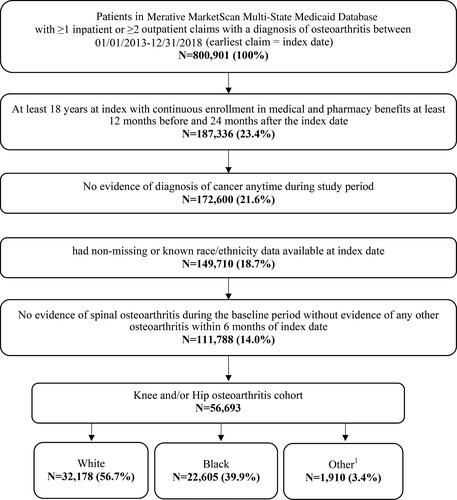

Adults (18 years or older) with ≥1 non-diagnostic inpatient claim with a diagnosis of OA in the primary position or ≥2 non-diagnostic outpatient claims with an OA diagnosis within 30 to 365 days apart on separate days between 1 January 2013, and 31 December 2018, were identified. Algorithms used to identify patients with OA were adapted from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse Chronic Conditions algorithm for osteoarthritisCitation25. All patients had to have continuous enrollment (CE) with medical and pharmacy benefits for 12 or more months prior to the index date and 24 or more months following the index date and have ≥ 1 non-diagnostic medical claim with an International Classification of Diseases, 9th and 10th revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM/ICD-10-CM) diagnosis code for knee and/or hip OA (Supplementary Table 1) within ±6 months of index date. Though dual enrollees in Medicare and Medicaid are included in the MarketScan Multi-State Medicaid Database, Medicare Part D claims are not available for these patients to assess pharmacy utilization. Dual enrollees in the MarketScan Multi-State Medicaid Database did not meet the requirement for continuous enrollment with medical and pharmacy benefits required to assess study outcomes. Patients were excluded if they had any evidence of cancer during the study period (ICD-9/10 codes in Supplementary Table 1) because guidelines for pharmacologic treatment of pain are different in patients with cancer. Patients with missing or unknown race/ethnicity data were also excluded. Patients with evidence of spinal OA without evidence of OA at another anatomical site during the baseline period were also excluded as this may be characteristic of a separate clinical entity rather than OA. Patient selection is summarized in .

Measures

Patient characteristics

Self-reported race was measured as the first non-missing race for each patient prior to the index date and categorized as White, Black, and Other (American Indian/Alaska native, Hispanic, Asian, Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander, two or more races, other). All racial groups were considered for inclusion; however, the Other race category was combined due to low frequency (<2% per subgroup) for race groups other than Black or White. Additional patient demographic characteristics were measured on the index date including age, sex, rural vs. urban residence, and health plan type. Baseline clinical characteristics were measured during the 12-month baseline period and identified using the presence of diagnosis codes on medical claims. Clinical characteristics measured during the baseline period included Deyo-Charlson Comorbidity Index (DCCI) score, use of pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic OA treatments, and presence of comorbid conditions (anxiety, cardiovascular disease, constipation, depression, diabetes, fibromyalgia, inflammatory arthritis, low back pain, neuropathy, obesity, other musculoskeletal pain, other neuropsychiatric disorders sleep disorders, and substance use/abuse). The presence of moderate to severe OA during the baseline period was assessed using a previously published claims-based algorithm to identify moderate to severe OA based on OA-related resource utilization (e.g. OA-related surgical procedures, use of mobility aids, total days’ supply of NSAIDS/opioids)Citation26.

Outcome measures

Given the chronic nature of OA and to evaluate longer term healthcare resource use and direct healthcare costs in knee and/or hip OA patients, outcomes were measured during a 24-month follow-up period and included pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic OA treatment, HCRU and costs. Pharmacologic treatment was identified in patients with medical or pharmacy claims for one or more of the following: acetaminophen, duloxetine, oral or intramuscular glucocorticoid, NSAIDs, opioids, other non-opioid combinations (NSAID and acetaminophen combinations), and prescription topical medications (NSAID, capsaicin). Non-pharmacological treatment from medical claims included physical/occupational therapy, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, and acupuncture or chiropractor therapies. All-cause HCRU and costs were calculated during baseline and follow-up periods. OA-related HCRU measures were defined from claims with an OA diagnosis, OA-related surgical procedures or medical and pharmacy claims for OA pharmacologic treatments. Measures included inpatient admissions, outpatient visits and services (including home health, skilled nursing facilities, and durable medical equipment), emergency room visits, office visits, OA medical costs and other outpatient services as well as outpatient prescriptions. Claims associated with an emergency room visit that resulted in an inpatient admission were considered part of the inpatient admission and costs. Cost for services provided under capitated arrangements for both managed care and fee-for-service plans were estimated using payment proxies that were computed based on paid claims at the procedure level using the MarketScan Commercial and Medicare Supplemental Databases. All costs were inflated to 2019 U.S. dollars using the medical component of the Consumer Price Index.

Statistical analysis

Bivariate analyses were conducted to compare baseline patient characteristics, use of pharmacological and non-pharmacological OA treatments, and HCRU and costs in patients with OA by race (White vs. Black; White vs. Other). Mean and standard deviation (SD) were reported for continuous variables and frequencies and percentages were reported for categorical variables. Patients with OA were compared across racial groups using Student’s t-test for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. A p-value of .05 was specified a priori as the threshold for statistical significance.

Multivariable analyses were conducted to describe racial differences in healthcare costs while controlling for underlying differences in the patients with OA. A two-part approach was used to estimate whether all-cause healthcare and OA-related costs differ by race while controlling for differences in patients’ baseline characteristicsCitation27,Citation28. Racial differences in odds of any healthcare costs were estimated using logistic regression, while racial differences in mean costs among patients incurring healthcare costs were estimated using a Gamma-family generalized linear model with a log linkCitation28. Covariate-adjusted costs were estimated using the recycled predictions methodCitation29. A set of core covariates including, age, sex, urban residence (Y/N), and mean healthcare costs during the baseline period were selected a priori for inclusion in the model. Variables included in the final model were selected using least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) which is suitable for variable selection in cases where predictors may be correlated and builds models with a reduced set of covariatesCitation30. Variables in the final model included race, age, sex, population density, plan type, presence of non-knee/hip OA, CVD, low back pain, musculoskeletal pain, presence of moderate to severe OA, and any pre-index costs. Descriptive analyses were conducted using WPS version 4.2 (World Programming, UK), while multivariable analyses were conducted using R version 3.6.3 (Vienna, Austria) and the “glmnet” packageCitation31.

Results

Patient characteristics

Of the total 56,693 patients with knee and/or hip OA included in the study, 56.7% were White, 39.9% were Black and 3.4% were of Other races (). Overall mean age was 49.4 years, and 72.4% were women. Most patients had only knee OA (79.7%), 14.6% had only hip OA, and 5.8% had both. A large proportion (73.9%) of study patients resided in urban areas, however, a higher percentage of White patients (33.9%) than Black patients (14.8%, p < .001 vs. White) or patients of Other race (26.3%, p < .001 vs. White) lived in rural areas. The mean baseline DCCI comorbidity index was 0.6 (SD: 1.3) overall and did not significantly differ across race categories. Moderate to severe OA was present in 49.2% of Other races, 45.4% of White patients, and 41.5% of Black patients.

Table 1. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics among patients with knee and/or hip osteoarthritis.

Comorbid conditions were present across the race categories (≥1 condition: 49.6%, 47.0%, 55.6% for White, Black, and Other race respectively). Rates of comorbid conditions in White patients were generally higher than in Black patients; White patients were diagnosed with depression and anxiety at rates >5% higher than Black patients.

Non-pharmacologic and pharmacologic treatments

The use of non-pharmacologic treatments, including physical therapy, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, acupuncture, or chiropractor, varied by race and were most common among patients of Other race (42.4%), followed by White patients (37.4%) and Black patients (33.4%) (). Pharmacological treatment for OA during the 24-month follow-up was high across race categories (93.8% overall). Opioids and NSAIDs were the most commonly used types of pharmacologic treatment for OA. Opioids were most commonly prescribed in White patients (82.0%) followed by patients of Other race (80.1%); rates of opioid prescription were lowest in Black race (79%) though prescriptions for tramadol opioids were more common in this group (33.9%) than in White patients (30.2%) and patients of Other race (32.2%).

Table 2. Osteoarthritis pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic treatment during 24-month follow-up period.

Healthcare utilization and costs

All-cause inpatient admission during the 24-month follow-up period was highest in White patients (28.3%) and patients of Other race (26.2%, p=.056 White vs. Other) and lowest among Black patients (25.8%, p < .001 vs. White vs. Black) (). For outpatient visits, ER visits were higher in Black patients (65.7%) compared to White (62.6%, p < .001) and Other race (62.3%, p=.77 White vs. Other). The proportion of patients with an outpatient prescription was high across all racial categories; 98.2% vs. 96.5% vs. 98.5% in White, Black, and Other race respectively. OA-related trends were similar to all-cause HCRU with the lowest patient admissions in Black patients (7.5%) compared to White patients (9.6%, p < .001) or Other race (9.7%, p =.79 White vs. Other) (). ER visits were higher in Black patients (17.7%) compared to White patients (13.6% p < .001) and Other race (12.9% p=.408 White vs. Other).

Table 3. All-cause healthcare resource utilization among patients with knee and/or hip osteoarthritis.

Table 4. OA-related healthcare resource utilization among patients with knee and/or hip osteoarthritis.

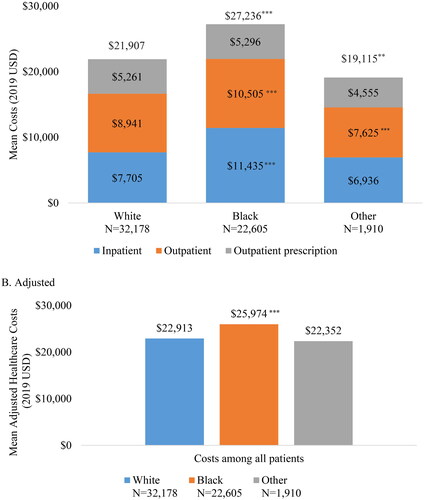

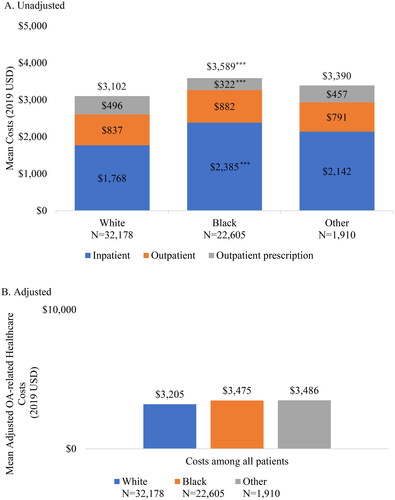

Mean all-cause inpatient costs during the 24-month follow-up period were highest in Black patients compared to White patients ($11,435, SD: $57,482 vs. $7,705, SD: $41,403; p < .001). (). Mean all-cause outpatient costs were also higher in Black patients ($10,505, SD: $20,103) compared to White patients ($8,941, SD: $19,765), p < .001 White vs. Black). Mean all-cause healthcare costs were highest in Black patients ($27,236, SD: $86,617; p < .001 White vs. Black) followed by White patients ($21,907, SD: $54,598) and patients of Other race ($19,115, SD: $48,180, p = 0.029 White vs. Other). Trends in OA-related HCRU and expenditures differed slightly, with higher outpatient prescription costs in White patients ($496 SD: $2,172), compared to Black patients ($322, SD: $1,743; p < .001 White vs. Black), but no significant differences in outpatient costs across the race categories (). Similar to all-cause costs findings, Black patients had the highest OA-related inpatient costs ($2,385, SD: $16,234) compared to $1,768 (SD: $13,685, p < .001 White vs. Black) in White patients and $2,142 (SD: $13,076) in patients of Other race.

Figure 2. Mean all-cause healthcare costs during 24-month follow-up period.

*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001 comparing White vs. Black and White vs. Other adjusted mean costs

Adjusted for age, sex, population density, plan type, presence of non-knee/hip osteoarthritis, cardiovascular disease, low back pain, musculoskeletal pain, presence of moderate to severe osteoarthritis, and any pre-index costs.

Figure 3. Osteoarthritis-related healthcare costs during 24-month follow-up period.

*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001 comparing White vs. Black and White vs. Other Adjusted for age, sex, population density, presence of hip osteoarthritis, and any pre-index osteoarthritis-related costs.

In the multivariable-adjusted models, all-cause expenditures among Black patients remained significantly higher than in White patients ($25,974 vs. $22,913, p < .001). The differences in expenditures between White patients and patients of Other race ($22,352) were no longer statistically significant. (). OA-related expenditures were similar in Black ($3,475), White ($3,205), and Other ($3,486) race patients after adjusting for underlying differences in baseline patient characteristics ().

Discussion

This retrospective analysis of Medicaid claims data has shown significant racial variations in healthcare resource use and costs among Medicaid patients with OA. As expected, use of pharmacological treatments as well as all-cause healthcare utilization was high in this population. When comparing use of pharmacologic treatments for OA by racial group, White patients had significantly higher rates of prescription for opioids (overall and when assessing only non-tramadol opioids) relative to Black patients, though Black patients had higher prescription rates for tramadol opioids. White patients also had a significantly higher proportion of patients with at least one hospitalization relative to Black patients, while the rate of ER visits was significantly higher in Black patients. Though the proportion of patients with an inpatient admission was lower in Black patients and a number of inpatient admissions and length of hospitalization were similar to White patients, mean costs for inpatient care were significantly higher in Black patients. Total healthcare costs were also significantly higher in Black patients when compared to White patients, despite lower rates of use of pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic OA treatments and inpatient admissions. These differences persisted in adjusted models after controlling for underlying differences in rural vs. urban residence, age, presence of moderate to severe OA, and presence of baseline comorbidities.

Medicaid patients with knee/hip OA had substantial HCRU in this claims-based study. Prior studies on HCRU in commercially insured populations have also reported higher utilization and costs among patients with OA, consistent with our findingsCitation22,Citation23. In a study of commercially insured patientsCitation22, reported higher total healthcare costs in knee patients with OA compared to controls (mean costs $24,550 vs. $16,843 PPPY, p < .001). Similarly, a study of privately insured patients with OACitation23 found higher total medical costs in patients with OA vs. controls ($14,521 vs. $3,629; p < .001) and reported higher outpatient and emergency room costs in patients with OA compared to controls. Neither study was able to examine differences in patterns of resource use by race or account for other socioeconomic factors as these data are lacking in many administrative claims databases.

This study extends prior research by showing significant racial variation in HCRU and costs in a Medicaid population with a more homogenous socioeconomic status than a commercially insured population. Though racial variation in the use of total joint replacement have been documented in prior studies, these studies have largely focused on commercially insured populationsCitation20,Citation21. A prior study of Medicaid patients showed rates of opioid used to treat acute and chronic pain were higher in White patients than in Black patients, similar to the findings of the current studyCitation32; however, this study was not focused on patients with OA and did not describe racial difference in other healthcare resource utilization or costs. The higher healthcare spending in Black patients observed in the current study is also consistent with prior research. An analysis of healthcare spending found that Black patients spent 19% more than the population average on inpatient visits, 12% more on emergency room care and 12% less on ambulatory care, though these costs were not OA specificCitation24.

The higher all-cause and OA-related expenditures in Black patients, despite lower rates of HCRU, could be attributed to significantly higher inpatient and outpatient costs in Black patients relative to White patients. Higher inpatient costs in Black patients cannot be attributed to either longer or more frequent hospitalizations; no significant difference in either the length of stay or the number of hospitalizations was observed when comparing Black patients to White patients. Differences in underlying comorbidity profile of Black patients and White patients may partially explain the observed differences in cost as all-cause cost differences between Black and White patients decreased when controlling for OA severity and comorbidity and no significant differences in OA-related costs were observed following multivariable adjustment. However, significant racial differences in all-cause costs persisted after adjusting for baseline comorbidity profile. Taken together, these results suggest that other unmeasured patient characteristics including delayed access to care, barriers to accessing care, and differences in health-seeking behaviors may be driving increased costs in Black patients with OA. Future research should examine how factors such as these may impact healthcare expenditures among all patients with OA. Prospective studies examining the patient journey following incident OA diagnoses may provide better insights on the racial differences in the treatment, and healthcare utilization in patients with OA.

The limitations in this study include those inherent in retrospective administrative claims analysis. These data were not collected for research purposes and may be subject to missed or incorrect coding which may have introduced bias or measurement error. HCRU and use of pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic treatment was assessed using medical and pharmacy claims; only medical care or pharmacologic treatment that resulted in a Medicaid claim was included in the analyses. Care for which no claim was generated (e.g. over counter medications) or other indirect costs (e.g. work loss, transportation, caregiver burden) were not measured in this claims database. Additionally, race/ethnicity was categorized as White, Black, and Other race due to small number of cases in races other than White and Black. The racial groups included in the Other category were heterogenous and made up 3.4% of the study population, which may limit our interpretation, with respect to the Other race category. In addition, the demographic profile of the state Medicaid databases that contribute to the MarketScan Multi-State Medicaid file may not be representative of Medicaid patients nationally. Hispanic patients in particular may be underrepresented in the Multi-State Medicaid DatabaseCitation33. Further research is necessary to describe disparities in the burden of OA among patients in non-Black racial minority groups. Finally, there may be systematic differences between our comparison groups that account for differences found in healthcare costs and utilization. While differences between comparison groups were controlled for by multivariate regressions to minimize bias, adjustment was limited to those characteristics that could be measured from administrative claims.

Conclusions

We found racial differences in all-cause healthcare expenditures in patients with OA within Medicaid. Black patients had higher all-cause healthcare costs compared to White patients, and patients of Other race and this difference persisted even after adjusting for age, sex, region, rural vs. urban residence, severity of OA, underlying comorbid conditions, and pre-index costs. These higher costs were driven by higher inpatient expenditures despite the fact that Black patients had significantly lower inpatient admissions compared to White patients, suggesting that inpatient admissions in Black OA patients may be more complex (and thus more costly) than inpatient admissions in White OA patients. These further findings indicate that there is an unmet need in OA management in Black patients with OA and extend findings from previous studies by showing racial disparities in healthcare resource use and expenditures in a Medicaid population, despite a more homogenous socioeconomic status. This study therefore suggests that race is an important risk factor for increased healthcare expenditures and more complex inpatient admission in Black OA patients, independent of socioeconomic status.

Transparency

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Ethics approval and informed consent

All database records are statistically de-identified and certified to be fully compliant with US patient confidentiality requirements set forth in the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996. Because this study used only de-identified patient records and did not involve the collection, use, or transmittal of individually identifiable data, this study was exempted from Institutional Review Board approval.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (14.3 KB)Acknowledgements

Additional support for the analysis and interpretation of the results was provided by Lorena Lopez-Gonzalez, of IBM Watson Health and funded by Eli Lilly Company and Pfizer. Medical writing support was provided by Donna McMorrow and Claire Bosire, of Merative (IBM Watson Health at the time the study was conducted) and funded by Eli Lilly Company and Pfizer. Programming services were provided Caroline Henriques of Merative (IBM Watson Health at the time the study was conducted) and funded by Eli Lilly Company and Pfizer.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

SS is Clinical Professor of Medicine at University of California Los Angeles, David Geffen school of medicine and at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center and a paid consultant to Eli Lilly and Pfizer. EP is an employee Merative (IBM Watson Health at the time of the study) which was contracted by Eli Lilly to conduct this study. AZ, CH, and RR are employees and stockholders of Eli Lilly. ST, PS, and WF are employees of Pfizer with stock and/or stock options. NMZ was an employee of IBM Watson Health which was contracted by Eli Lilly to conduct this study at the time of the study. This research was presented in part at the PAINWeek Conference, September 2021 in Las Vegas, NV, USA.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Merative. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study.

Additional information

Funding

References

- CDC. Osteoarthritis. Center for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Accessed at: https://www.cdc.gov/arthritis/basics/osteoarthritis.htm. September 10, 2021.2020 [cited.

- He Y, Li Z, Alexander PG, et al. Pathogenesis of osteoarthritis: risk factors, regulatory pathways in chondrocytes, and experimental models. Biology. 2020;9(8):194–227. PubMed PMID: 32751156; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7464998. eng. doi: 10.3390/biology9080194.

- Liang L, Moore B, Soni A. National inpatient hospital costs: the most expensive conditions by payer, 2017. HCUP statistical brief. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2020.

- Kolasinski SL, Neogi T, Hochberg MC, et al. 2019 American college of rheumatology/arthritis foundation guideline for the management of osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res . 2020;72(2):149–162. PubMed PMID: 31908149; eng. doi: 10.1002/acr.24131.

- van Laar M, Pergolizzi JV, Jr., Mellinghoff HU, et al. Pain treatment in arthritis-related pain: beyond NSAIDs. Open Rheumatol J. 2012;6:320–330. PubMed PMID: 23264838; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3527878. eng. doi: 10.2174/1874312901206010320.

- Geenen R, Overman CL, Christensen R, et al. EULAR recommendations for the health professional’s approach to pain management in inflammatory arthritis and osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018; 77(6):797–807. PubMed PMID: 29724726; eng. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-212662.

- Arden NK, Perry TA, Bannuru RR, et al. Non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis: comparison of ESCEO and OARSI 2019 guidelines. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2021; 17(1):59–66. PubMed PMID: 33116279; eng. doi: 10.1038/s41584-020-00523-9.

- Silverman S, Schepman P, Rice JB, et al. POS0283 Treatment patterns and clinical characteristics of patients with osteoarthritis of the hip and/or knee treated with traditional NSAIDS vs COS-2S: a real-world study of commercially-insured patients. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80:366–367.

- Xie F, Kovic B, Jin X, et al. Economic and humanistic burden of osteoarthritis: a systematic review of large sample studies. Pharmacoeconomics. 2016;34(11):1087–1100. PubMed PMID: 27339668; eng. doi: 10.1007/s40273-016-0424-x.

- Gore M, Sadosky AB, Leslie DL, et al. Therapy switching, augmentation, and discontinuation in patients with osteoarthritis and chronic low back pain. Pain Pract. 2012; Jul12(6):457–468. PubMed PMID: 22230466; eng. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2011.00524.x.

- Watt FE, Gulati M. New drug treatments for osteoarthritis: what is on the horizon? Eur Med J Rheumatol. 2017; 2(1):50–58. PubMed PMID: 30364878; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6198938. eng.

- Zhao X, Shah D, Gandhi K, et al. Clinical, humanistic, and economic burden of osteoarthritis among noninstitutionalized adults in the United States. Osteoar Cartil. 2019; 27(11):1618–1626. PubMed PMID: 31299387; eng. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2019.07.002.

- Salmon JH, Rat AC, Sellam J, et al. Economic impact of lower-limb osteoarthritis worldwide: a systematic review of cost-of-illness studies. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2016; 24(9):1500–1508. PubMed PMID: 27034093; eng. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2016.03.012.

- Schepman P, Thakkar S, Robinson R, et al. Moderate to severe osteoarthritis pain and its impact on patients in the United States: a national survey. J Pain Res. 2021;14:2313–2326. PubMed PMID: 34349555; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC8326774. eng. doi: 10.2147/jpr.s310368.

- Huckleby J, Williams F, Ramos R, et al. The effects of race/ethnicity and physician recommendation for physical activity on physical activity levels and arthritis symptoms among adults with arthritis. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1564. PubMed PMID: 34407795; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC8371891. eng. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11570-6.

- Vaughn IA, Terry EL, Bartley EJ, et al. Racial-Ethnic differences in osteoarthritis pain and disability: a Meta-Analysis. J Pain. 2019; 20(6):629–644. PubMed PMID: 30543951; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6557704. eng. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2018.11.012.

- McClendon J, Essien UR, Youk A, et al. Cumulative disadvantage and disparities in depression and pain among veterans with osteoarthritis: the role of perceived discrimination. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2021; 73(1):11–17. PubMed PMID: 33026710; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7775296. eng. doi: 10.1002/acr.24481.

- Reyes AM, Katz JN. Racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in osteoarthritis management. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2021; 47(1):21–40. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2020.09.006.PubMed PMID: 34042052; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC8161947. eng.

- Yu S, Mahure SA, Branch N, et al. Impact of race and gender on utilization rate of total shoulder arthroplasty. Orthopedics. 2016;39(3):e538-44–e544. PubMed PMID: 27135458; eng. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20160427-14.

- Skinner J, Weinstein JN, Sporer SM, et al. Racial, ethnic, and geographic disparities in rates of knee arthroplasty among medicare patients. N Engl J Med. 2003; 349(14):1350–1359. PubMed PMID: 14523144; eng. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa021569.

- Singh JA, Lu X, Rosenthal GE, et al. Racial disparities in knee and hip total joint arthroplasty: an 18-year analysis of national medicare data. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(12):2107–2115. PubMed PMID: 24047869; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4105323. eng. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203494.

- Bedenbaugh AV, Bonafede M, Marchlewicz EH, et al. Real-World health care resource utilization and costs among US patients with knee osteoarthritis compared with controls. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2021;13:421–435. PubMed PMID: 34054301; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC8153072. eng. doi: 10.2147/ceor.s302289.

- Wang SX, Ganguli AX, Bodhani A, et al. Healthcare resource utilization and costs by age and joint location among osteoarthritis patients in a privately insured population. J Med Econ. 2017;20(12):1299–1306. PubMed PMID: 28880733; eng. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2017.1377717.

- Dieleman JL, Chen C, Crosby SW, et al. US health care spending by race and ethnicity, 2002-2016. Jama. 2021;326(7):649–659. PubMed PMID: 34402829; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC8371574. eng. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.9937.

- Chronic Conditions Warehouse: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 2022 updated 2/2022; cited 2022 8 August]. Available from: https://www2.ccwdata.org/web/guest/condition-categories-chronic.

- Berger A, Robinson RL, Lu Y, et al. Creation and validation of algorithms to identify patients with moderate-to-Severe osteoarthritis of the hip and/or knee and inadequate/intolerable response to multiple pain medications. Postgrad Med. 2020;132:58–59.

- Deb P, Norton EC. Modeling health care expenditures and use. Annu Rev Public Health. 2018;39:489–505. PubMed PMID: 29328879; eng. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040617-013517.

- Pagano E, Petrelli A, Picariello R, et al. Is the choice of the statistical model relevant in the cost estimation of patients with chronic diseases? An empirical approach by the piedmont diabetes registry. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:582. PubMed PMID: 26714744; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4696194. eng. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-1241-1.

- Hays RD, Spritzer KL. REcycled SAS® PrEdiCTions (RESPECT). presented at the society for computers in psychology. Toronto, Canada: UCLA Department of Medicine; 2013.

- Sauerbrei W, Perperoglou A, Schmid M, et al. State of the art in selection of variables and functional forms in multivariable analysis-outstanding issues. Diagn Progn Res. 2020;4:3. PubMed PMID: 32266321; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7114804. doi: 10.1186/s41512-020-00074-3.

- Simon N, Friedman J, Hastie T, et al. Regularization paths for cox’s proportional hazards model via coordinate descent. J Stat Softw. 2011;39(5):1–13. PubMed PMID: 27065756; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4824408. eng. doi: 10.18637/jss.v039.i05.

- Janakiram C, Fontelo P, Huser V, et al. Opioid prescriptions for acute and chronic pain management among medicaid beneficiaries. Am J Prev Med. 2019;57(3):365–373. PubMed PMID: 31377093; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6713282. eng. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.04.022.

- Distribution of the Nonelderly with Medicaid by Race/Ethnicity: Kaiser Family Foundation. [cited 2023 7 Apr 2023]. Available from: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/medicaid-distribution-nonelderly-by-raceethnicity/.