Abstract

Background

Public preferences are an important consideration for priority-setting. Critics suggest preferences of the public who are potentially naïve to the issue under consideration may lead to sub-optimal decisions. We assessed the impact of information and deliberation via a Citizens’ Jury (CJ) or preference elicitation methods (Discrete Choice Experiment, DCE) on preferences for prioritizing access to bariatric surgery.

Methods

Preferences for seven prioritization criteria (e.g. obesity level, obesity-related comorbidities) were elicited from three groups who completed a DCE: (i) participants from two CJs (n = 28); (ii) controls who did not participate in the jury (n = 21); (iii) population sample (n = 1,994). Participants in the jury and control groups completed the DCE pre- and post-jury. DCE data were analyzed using multinomial logit models to derive “priority weights” for criteria for access to surgery. The rank order of criteria was compared across groups, time points and CJ recommendations.

Results

The extent to which the criteria were considered important were broadly consistent across groups and were similar to jury recommendations but with variation in the rank order. Preferences of jurors but not controls were more differentiated (that is, criteria were assigned a greater range of priority weights) after than before the jury. Juror preferences pre-jury were similar to that of the public but appeared to change during the course of the jury with greater priority given to a person with comorbidity. Conversely, controls appeared to give a lower priority to those with comorbidity and higher priority to treating very severe obesity after than before the jury.

Conclusion

Being informed and undertaking deliberation had little impact on the criteria that were considered to be relevant for prioritizing access to bariatric surgery but may have a small impact on the relative importance of criteria. CJs may clarify underlying rationale but may not provide substantially different prioritization recommendations compared to a DCE.

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY

Public preferences are an important consideration for priority-setting. However, some people worry that if the public doesn’t know much about the issues, their opinions might not lead to the best decisions. To make these decisions, we used two different methods to get people’s opinions: Deliberative methods and preference elicitation methods. Deliberative methods gather a small group of people and have them discuss an issue in detail, whereas preference elicitation methods seek opinions through surveying a large group of people.

In this paper, we assessed the impact of information and deliberation via a deliberative method (Citizens’ Jury, CJ) or a preference elicitation method (Discrete Choice Experiment, DCE) on preferences for prioritising access to bariatric surgery. We used data from two CJs and a DCE focussed on prioritising access to the surgery, to find out if the opinions of those in the CJs changed or stayed the same after they heard information from experts and discussed the topic.

The results showed that the important criteria were rather similar across the groups, but the order of importance was a bit different. The people in CJs had more varied opinions after discussing it, while those who didn’t discuss it had less varied opinions. The participants in CJs also prioritized those with other health problems more than they did at the beginning.

This study helps us understand how different methods can be used to get the public’s opinions on healthcare decisions.

Introduction

Public preferences are an important consideration for the prioritization of health care services. Greater participation by citizens can increase the chance of successful policy implementation, legitimize the decision-making process and its final result, and increase the scope for partnership with citizensCitation1. Further, consideration of the preferences of health service end users has the potential to improve the uptake of services and adherence to treatment regimens, maximize the overall efficiency of services by informing them of which treatments and outcomes are most strongly valued, and promoting the responsiveness of service provision to meet user demands. Consequently non-deliberative methods that elicit participants’ stated preference, such as the discrete choice experiment (DCE), are now a popular approach to evaluate public and patient preferences for health careCitation2.

Alongside the development of non-deliberative methods to evaluate stated preferences for health care, the validity of these approaches has been explored. In particular, investigators have debated whether stated preference methods such as the DCE conform to underlying axioms and the assumptions of consumer welfare and random utility theory upon which they are basedCitation3. Many stated preference methods, including the DCE, rely on the aggregation of preferences across the sample as the mechanism by which they contribute to democratic decision-makingCitation4. The theoretical assumptions underlying stated preference methods include that preferences are complete or well formed and stable, that is they do not change over repeated elicitations or timeCitation3,Citation5. Dolan et al. reported public views related to setting health care priorities to be systematically different when the general public are given the opportunity to deliberate, arguing that not allowing respondents time to reflect or deliberate may not be a useful mechanism for eliciting public opinionCitation6. As such, it could be contended that participants in stated preference studies should be informed and potentially have the opportunity to deliberate an issue, subject to practical and resource constraints, before their preferences are elicitedCitation7.

It is generally accepted that to avoid self-interest and possible bias, preferences used to inform health care decision-making and policy should be elicited from the general (national tax-paying) public rather than patients specificallyCitation8. This is particularly important when decisions related to resource allocation or service design might differentially affect patient groups or impact upon society more widely beyond any specific patient group. This dichotomy produces a conundrum; how do we obtain complete and stable preferences from a sample of a sufficiently informed yet unbiased general public, where the sample is also large enough to be considered representative of society more broadly?

Deliberative forum such as the Citizens’ Jury (CJ) are employed to allow public input to health policy decision-makingCitation9–15. A Citizens’ Jury typically consists of 12–16 individuals who are recruited from the community affected by the decision, who meet over several days to hear evidence from experts and to deliberate the issue at handCitation12. These methods are only generally feasible with relatively small samples which are too small to be considered representative of wider society. Conversely, the use of survey-based stated preference methods such as the DCE facilitate the elicitation of preferences from potentially large and more representative population samples. Nevertheless, these large population samples can generally be criticized for being relatively uninformed of the issue at hand. Providing information and encouraging deliberation before a decision has been claimed to be important to promote “better” determination and the formation of complete and stable preferencesCitation16–18. However, the optimal method (or combination of methods) for engaging the public and considering their preferences in prioritization decisions is not yet clearCitation4.

This paper makes an empirical contribution to our understanding of whether information and deliberation make a difference to preferences and therefore provides insight into the validity of preference elicitation, when considering the application of non-deliberative stated preference methods in a priority setting context. We aim to provide insights into the debate over which method/s or combination of methods might be useful to elicit and consider public preferences in prioritization decisions. Specifically, we utilize data from two CJs and a DCE undertaken in three different participant groups in the context of prioritizing patients for bariatric surgery to investigate whether the preferences of participants in a CJ change or become more stable (reproducible) as a result of the provision of information and deliberation. Based on previous researchCitation6,Citation19, it is possible that the provision of information and deliberation may result in the preferences of people who participate in a CJ changing after participating in the jury but also becoming more stable. We also explore how consistent the preferences of an uninformed public are with the preferences of jurors after undertaking a CJ, and how closely aligned the recommendations made by each CJ following the provision of information and deliberation are with either the aggregated preferences of jurors after deliberation or with the preferences of the general public.

Methods

This study was nested within a larger program of research funded by the Australian Research Council to facilitate the identification and application of optimal methods for engaging the public in healthcare decision-makingCitation20. The funding partners chose the specific decision-making context of prioritizing access to bariatric surgery as being a pertinent issue for efficient and responsive health service delivery. Bariatric surgery is in high demand as it has the potential to achieve sustained weight loss and improve obesity-related comorbidities such as type II diabetes mellitusCitation21. However, many public health systems have limited capacity to expand service provision and there are inequities in access to surgery for people who would be expected to benefitCitation22,Citation23. The limited resources available to meet the apparent demand for bariatric surgery make it desirable to seek public views on what basis could be used to prioritize access for those who might benefit. We sought the views and preferences of the public as they relate to priority setting at a policy level (sometimes referred to as social value judgments) rather than at a bedside levelCitation24.

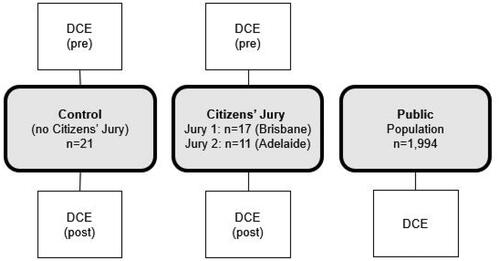

An overview of the research design is provided in . Two separate CJs were held on the topic, one in Brisbane (held over 3 d) and one in Adelaide (held over 1 d). Three groups were invited to complete a DCE: An intervention group, consisting of the 28 members of the public participating in either CJ; a control group consisting of 21 individuals selected alongside the jurors but who did not participate in the jury, and a large sample of the general public selected so as to be representative of the population by age and gender. The jurors and controls were invited to complete the DCE at two time points: pre-jury (within 7 d before the jury) and immediately post-jury. The Brisbane jurors were provided with meals, accommodation, travel reimbursement and a stipend of $275 for the 3 d and the Adelaide jurors were provided with lunch, a stipend of $120 and reimbursement of travel expenses for their 1 d jury. The control group were given $50 for completion of their DCEs. The public sample undertook the survey within 6 months of the CJs being held and were incentivized directly by Pure Profile.

The methods and findings of the two CJs and the public DCE have been previously reportedCitation23,Citation25,Citation26. We draw on these findings and on the unpublished juror and control DCE data to address the research questions for the current study.

Participants

The study was approved by Griffith and Flinders University Human Research Ethics Committees (MED/09/12/HREC; 6088 SBREC).

Jurors and controls

Adults (aged 18 years or over) were eligible to participate in the jury or control groups if they lived in the southern metropolitan district of Brisbane or in South Australia (Adelaide jury). Individuals were excluded if they were affiliated with a special interest healthcare group, were employed as a health professional, had experience in the weight loss industry, or had previously undergone bariatric surgery.

For the Brisbane jury, a sample of 2,000 adults in Queensland were randomly selected from the electoral roll within the southern metropolitan district of Brisbane and invited to express their interest to participateCitation25. Over 15% (n = 314) respondents indicated they were interested and had not participated in a previous (unrelated) CJ which had taken place in phase one of the study. From these, 140 (44%) respondents returned a screening survey, 112 (80%) of these were eligible to participate, and 50 (36% of those eligible to participate) were available. Twenty-four of those eligible and available were selected to reflect the Queensland population by age and gender and invited to participate in the Brisbane CJ. Eighteen agreed to participate in the Brisbane CJ but one person became unwell during the jury and discontinued. Thus, 17 jurors attended the Brisbane jury and all completed the DCE at both time points.

Electoral rolls were not available in Adelaide so recruitment utilized convenience sampling through advertisements in local newspapers and general practices. Twelve (86%) of 14 eligible respondents to the advertisement attended the Adelaide jury; of these 11 (92%) completed the DCE at both time points (the twelfth person did not complete the DCE post-jury).

We had originally intended to invite participants to the control group who were matched to the jurors by age and gender. However, we were unable to achieve this due to limitations in the size of the eligible respondent pool after the selection of the jury in Brisbane and the recruitment method used in Adelaide. Therefore, all respondents who were not participants in the juries were invited to the control group (26 from Queensland, 2 from Adelaide). Of the 28 controls invited, 21 (75%) completed the DCE at both time points.

Citizens’ jury (CJ)

The CJ was convened over 3 consecutive days in Brisbane and over 1 d in AdelaideCitation25. Participants (“jurors”) were mailed an information pack containing logistical information and the DCE approximately 5 d prior to the jury and asked to return the DCE at the start of the CJ (DCE pre-jury). At the CJ, jurors were asked to deliberate and make recommendations around four questions related to the prioritization of people with obesity for bariatric surgery. Pertinent to this paper, the second question they were asked was: “What should be the criteria for prioritizing people for treatment? (i.e. how should we decide who gets the surgery first)”.

The jury design considered the principles of a good jury process, which promote the legitimacy in the selection of both participants and experts and the extent to which they represent wider views, the legitimacy of the procedure through allowing sufficient time for deliberation and placing emphasis on challenging experts, and the provision of accessible informationCitation26,Citation27. Expert witnesses presented evidence to the participants on the topic of obesity in plenaries in the first half of each jury, with a particular focus on the role and impact of bariatric surgeryCitation25. The expert witnesses for the Brisbane jury were an epidemiologist, physiotherapist, psychologist, dietician, bariatric surgeon, three consumers (weight loss without surgery, recent surgery and surgery 6 years previous) and an endocrinologist. The Adelaide jury’s expert witnesses were a renal specialist, upper gastrointestinal surgeon, bariatric surgery coordinator, dietician, psychologist, exercise physiologist and three consumers (waitlist for surgery, and two who had undergone surgery in the previous 18 months). The experts presented information on obesity and its management from their own professional disciplinary or consumer perspective which ranged from the burden of obesity and its consequences, the benefits and risks of surgery, pre-surgery management and the recovery process, and alternatives to surgery. The experts focused on clinical evidence supplemented with their experience, and the consumers reported on their personal lived experience. Both juries were facilitated by two independent facilitators who ensured there was time to digest information provided by experts, to challenge the experts and to seek further follow up information or clarification from the experts later in the jury, if required. The jurors then deliberated the evidence in small groups, and made their recommendationsCitation25. The process for the Adelaide jury was the same as for the Brisbane jury, with the same number of sessions, but a shorter period for small group discussion and deliberation. At the end of the CJ, jurors were asked to complete the same DCE survey a second time (DCE post-jury).

Control group

Participants in the control group were mailed the same DCE survey as the jurors approximately 5 d prior to the jury taking place (DCE pre-). However, they did not participate in the CJ. They were mailed a second copy of the DCE survey a week later (DCE post-) after they had returned their first survey.

Public population sample

We targeted a sample of 2,000 adults who lived in Queensland or South Australia via an online opt-in survey panel (PureProfile), and achieved a completed sample of 1994 participants for the public DCE. Quotas were used to ensure representation of each state by age and gender. The panel provider reimbursed participants with a small reward for their time.

Sample size

We chose to recruit a public sample of 2,000 to ensure a precise estimation of preference parameters while also allowing flexibility in modeling heterogeneityCitation28,Citation29. The sample size for the juror and control DCEs were restricted by pragmatic design considerations. CJs ideally consist of between 12 and 24 jurorsCitation15. Appropriate sample size for DCEs depends on many factors including the number of attributes and levels chosen for each attribute and the extent to which subgroup analyses is desired. Whilst we aimed toward the upper end of this for our Brisbane jury, the analyses are not powered to quantitatively test for any difference in preference between samples. Therefore, the analyses reported in this paper are descriptive and qualitatively examine differences in ranking criteria derived using the DCE data.

Discrete choice experiment (DCE) survey

We have previously described the design of the DCE and its use to elicit public priority weightsCitation23. In brief, participants were asked to prioritize access to surgery between two hypothetical patients, each of whom would be expected to benefit from surgery to manage their obesity. The patients were described using seven attributes with two or three levels used to describe each attribute (Box 1)Citation23. The attributes and levels used to describe the potential prioritization criteria were developed based on a literature review and refined through an expert focus groupCitation23.

Box 1 DCE attributes and levels shown to the respondents

Current level of obesity: Obesity (BMI 30 to less than 40 kg/m2); Severe Obesity (BMI 40 to less than 50 kg/m2); Very Severe Obesity (BMI greater than 50 kg/m2)

Obesity-related conditions: Already has obesity-related conditions; Is at risk of developing obesity-related conditions

Age of person needing surgery: 20 years; 35 years; 50 years

Family history: At least one parent or sibling is obese, has had weight issues since childhood; No family history of obesity

Chance of maintaining a substantial (at least half) reduction in excess weight: 30%; 50%; 70%

Has shown commitment by responding to prescribed lifestyle intervention (i.e. physical activity and diet): Has maintained a healthy lifestyle plan for several months, resulting in some weight loss, however is still in need of surgery; Has not maintained a healthy lifestyle plan and has had no weight loss

Time already spent on surgery waiting list: 6 months; 1 year; 2 years

Note: Contents reproduced from Whitty et al. 2015 with permissionCitation23.

We specified a Dp-efficient fractional factorial design using NGENE softwareCitation30. This design selects the optimal combination of profiles to present for each choice set in the DCE in such a way that maximizes the statistical efficiency of the design and therefore the precision of the preference estimates. We considered the use of an efficient design approach to be particularly important here given the small sample sizes available for the jury and control samples. The resulting design contained 18 choice sets for each participant to complete. The public sample also completed choice sets specified using a second much larger Dp-efficient design consisting of 9 blocks of 18 choice sets. Thus, the public were randomized to complete one of 10 survey versions (the choice set block used for the jurors and controls plus the 9 additional blocks) each consisting of 18 choice sets. For all samples, one choice set was reversed and repeated as a 19th choice set in the survey. This enabled an exploration of any difference in internal consistency between samples within a single survey and time point.

Analysis and comparison of preferences across groups and time points

(columns 1–4) provides a summary of the analytic approach taken to address each research objective. For each sample and time point, we estimated a discrete choice model using NLOGIT softwareCitation31 to derive priority weights for each of the prioritization criteria, using the approach previously detailedCitation23. A multinomial logit (MNL) model was specified for each of the five DCE datasets (CJ pre- and post-jury, Control pre- and post-, and Public survey)Citation32. Within a given sample or time point, the model coefficients indicate the relative importance of each attribute level in explaining participant choice. All attributes were specified as categorical with effects codingCitation33, except for the chance of maintaining weight loss and time of the wait list, which were specified using continuous coding.

Table 1. Summary of approach to addressing the research objectives and related hypotheses, and summary of findings (last column).

We then derived “priority weights” from the MNL model coefficients, to indicate the relative importance of improvements in the different criteria. Priority weights were assigned by estimating the marginal rate of substitution between each prioritization criterion and effectiveness (i.e. chance of maintaining weight loss)Citation34. The rank order of priority weights can be used to descriptively compare the relative importance assigned to each criterion between samples and time points. We only derived priority weights for those attribute levels which were significant in explaining prioritization choices at the 10% level for at least one of the samples. We chose a 10% significance level to be more tolerant than the conventional 5% level given the small sample size for some preference groups and that our comparisons are predominantly descriptive.

We compared the rank order of “priority weights” measured by the DCE across the two time points and between groups to provide insight into the impact of information and deliberation on priorities. The number of choice sets for which jurors and controls made the same choice pre and post were described for each group at each time point. The analysis was predominantly descriptive given the small samples; however, exploratory analyses were used to test for any differences in choice consistency between groups using the Chi squared and t-test.

The repeat choice task within each survey was used to assess preference consistency and to evaluate the extent to which decision-making was “random”. We would expect individuals who are engaged with the choice task and who have stable, well-formed preferences to be more likely to give a consistent response to the repeat choice task within each survey. We used scatter plots to visually compare the preference weights between time points within each group, and between groups within each time point. When an individual is more consistent in respect to their use of attribute levels to drive their choices, they are likely to be less random in their responses, translating to a smaller error variance, relative to a less consistent respondent. The underlying scale of the model is reflected in the slope of the scatter plot and inversely related to the variance of the error term. Hence, in a scatter plot comparing the MNL coefficients estimated from two DCE datasets, a slope of 1 would indicate an identical underlying scale, identical variance in the error term, and an identical level of “randomness” in the responses given to the DCE choice sets. A slope less (greater) than 1 would indicate coefficients on the y-axis that are systematically smaller (larger) than those on the x-axis, suggesting a smaller (larger) underlying model scale, larger (smaller) variance in the error term, and greater (lesser) randomness in decision-making.

We also undertook a descriptive comparison between priority ranks estimated from the juror and public DCEs and the recommendations of the juries, to provide insight as to whether the deliberative method suggests different priorities to the DCE approach.

Results

Participant characteristics

The randomized stratified sampling used for the public DCE resulted in a sample that was closely representative of the Australian population in terms of age and sex. There were some differences in the demographic characteristics of the four groups (). The gender of the groups varied from 52% female for the public sample, to 72% for the Adelaide jury. The mean ages of the public sample, control group, and Adelaide jury were between 43 years and 47 years, with the mean age for a Brisbane juror being slightly older, at 54 years. The jurors and the control group were more likely to have undertaken post-secondary level education (71–82%) compared with the public sample (45%), and a higher proportion of Jurors, particularly from Adelaide, were overweight or obese (79%) than for controls (52%) or the public sample (60%). The jurors from Adelaide were also less likely to be partnered, less likely to be employed, and had lower incomes.

Table 2. Characteristics of participants in the two jury, control and public samples.

The results are described against each research objective below, and summarized in (column 5).

Impact of information and deliberation on preference structure across time

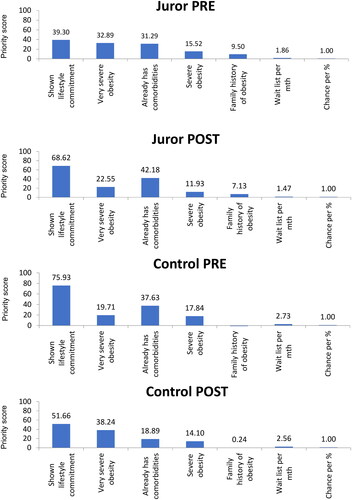

The jurors were less likely to give the same response to a choice set at both time points than were controls (Supplementary Appendix Table A1, row 1). On average jurors chose the same alternative in both surveys for 12.5 (SD 2.5) of the 18 choice sets compared to 14.4 (SD2.8) for controls (mean difference −1.9 t-test p = .017). This suggests that jurors were more likely to change their preference than controls. The MNL coefficients for each choice data set are presented in the Supplementary Appendix (Table A2). The priority weights derived from the MNL model for the jurors and controls at each time point are shown in , and the ranks are shown in . All attribute levels were significant in explaining prioritization choices at the 10% level for at least one of the samples except for recipient age, which did not appear to be an important prioritization criterion across any of the samples. At baseline, the juror and control preferences were similar with the exception that the rank order of importance placed on very severe obesity and comorbidities was reversed between the jurors and controls. That is, at baseline jurors prioritized commitment to lifestyle change as the most important criterion, treating those with very severe obesity as second priority, and treating those who already had obesity-related comorbidity as third priority. Controls also prioritised commitment to lifestyle change as the most important criterion, but for controls treating those who already had obesity-related comorbidity was ranked second, and treating those with very severe obesity was ranked third.

Figure 2. Priority weights for the juror and control samples, pre and post CJ deliberations (attributes are presented on the horizontal axis; possible priority scores range from 0 to 100 on the vertical axis).

Chance per % represents the priority score associated with a 1% increase in the chance of maintaining a substantial (at least half) reduction in excess weight.

Table 3. Rank order of priorities for juror and control DCE, pre and post.

Compared to before the jury, the jurors’ preferences after the jury became more differentiated (as indicated by the greater range of weights, ), and there was also a reversal in rank for positions 2 and 3, with surgery for people who already have comorbidities moving to a higher priority and surgery for people with very severe obesity moving to a lower priority after the jury as compared to before. However, preferences were also observed to change for controls who did not participate in the jury. Preferences became less differentiated and there was a reversal in rank for positions 2 and 3 in the opposite direction.

Impact of information and deliberation on preference consistency

At baseline, jurors, control participants and the public were all consistent to a similar extent on repeat choice tasks within the survey (Supplementary Appendix Table A1, row 2). However, jurors were less likely to give a consistent response to the repeat choice task after the jury than controls, with less than two-thirds (60.7%) jurors being consistent compared to nearly all (90.5%) of controls (Chi2 test p = .02).

Despite this observation, for the jurors, the preference weights post-jury are systematically larger than the preference weights pre-jury (Supplementary Appendix Figure A1(a), slope of line 1.1236). That is, the error term after the jury has a lower error variance than before the jury, meaning jurors became more consistent (less random) in their use of the attribute levels in decision-making after than before the jury. The converse is observed for controls (Supplementary Appendix Figure A1(b), slope of line 0.7156). After the jury, the preference weights for controls are systematically smaller than the preference weights for jurors (Supplementary Appendix Figure A1(c), slope of line 0.6876). This indicates a higher variance of the error term after the jury for controls than for jurors, meaning controls became less consistent (more random) in their use of the attribute levels in decision-making after than before the jury.

Consistency of the preferences of an uninformed public with the preferences of jurors after undertaking a CJ

The rank order of prioritization criteria for the public DCE was identical to that of the jurors DCE post jury, with the exception that the priority rank assigned to “very severe obesity” and “already has obesity-related comorbidity” are reversed (). It is interesting to note that the rank order assigned by the public DCE is most similar (in fact, identical) to that assigned by the jurors before they undertook the jury.

Overall, the juror preferences appeared to be similar to that of the general public before they undertook the jury, but they changed during the jury and differed from those of the public after the jury, leading to an increase in the priority that should be given to a person who already had obesity related conditions.

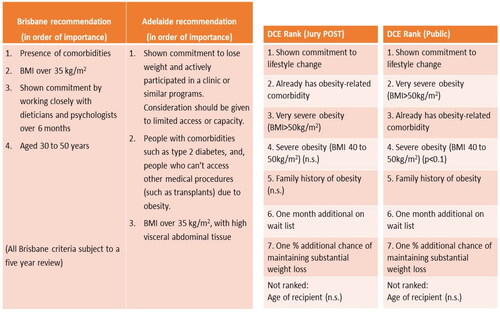

Alignment of the recommendations made by each CJ with the aggregated preferences of jurors after deliberation and with the preferences of the general public

The recommendations made by the two juries are provided in , along with the rank for criteria from the DCE of jurors post-jury and of the public for comparison. Both juries considered lifestyle commitment, BMI >35 kg/m2, and the presence of comorbidities to be important prioritization criteria, but the order of importance differed between the juries. In addition, the Brisbane jury considered that age could be used as a prioritization criterion; although, there was reluctance to use this. The jury suggested it be used only to prioritize in the short-term recognizing that the health service could not cope with the initial demand if bariatric surgery were to become publicly funded, but wanted the criteria to be reviewed in 5 years. As discussed above, there was also one key difference in ranking between the post-jury and public DCEs; namely, the jurors ranked obesity-related comorbidity more highly and the management of very severe obesity (BMI > 50kg/m2) less highly after the jury than did the public.

Figure 3. Comparison of the Jury recommendations and the DCE ranks for the jury post and public samples.

For the DCE, the attribute levels were significantly associated with the choices the respondents made at the 5% level (p < .05) with the exception of severe obesity and family history of obesity (which was only significant at the 10% level in some models, p < .1) and age of the recipient, which was not significantly associated with choice (n.s. p > .1).

The rank order for the juror’s top four criteria after the jury according to the DCE is identical to the recommendations made by the Adelaide jury. The remaining criteria were not specifically raised by the Adelaide jury as considerations. The top four criteria from the post jury DCE are also consistent with the top three criteria recommended by the Brisbane jury; however, the ordering of importance is different. Similar to the post-jury DCE, the top four criteria ranked by the public according to the public DCE were the same as the criteria used by the Adelaide jury recommendations. However, there was some inconsistency in the rank order between the public DCE and Adelaide jury, with the public prioritizing the treatment of those with very severe obesity (BMI > 50kg/m3) more highly than the Adelaide jury. The top four criteria from the public DCE are also consistent with the top three criteria recommended by the Brisbane jury; however as with the post-jury DCE, the ordering of importance is different. In addition, the Brisbane jury also considered that age could be used for prioritization (although this was the least important criterion); whereas neither the post jury DCE, public DCE, nor the Adelaide jury indicated age was an important consideration.

Overall, the criteria considered most important for both the juror and public DCEs are broadly aligned with the recommendations of the juries but with some variation in the rank order of importance. There is a slightly greater similarity to the jury recommendations for the DCE post jury than for the public DCE. However, there is also a similar level of variation in the importance of criteria between the two juries to that observed between the jury recommendations and the DCE.

Discussion

The question of how best to derive robust evidence on public views for consideration in decision-making is important for transparent and accountable priority setting in health careCitation30–33. This study is to our knowledge the first to empirically compare the findings from a method for which informing participants and enabling deliberation is fundamental, the citizens’ juries, with a method which is based on aggregation of preferences across a representative sample, the discrete choice experiment, for a prioritization task. Overall, the findings suggest being informed and undertaking deliberation had little impact on the criteria that were considered to be relevant for priority setting but did appear to impact to a small extent on the relative importance of those criteria. From this study, it seems unlikely that prioritization decisions based on recommendations from a CJ would be fundamentally different to those based on preferences elicited from a representative population sample using a DCE, in the context of prioritizing access to bariatric surgery. This is supported in particular by the similarity observed in the rank order of prioritization criteria for the public and jury sample with only a single preference reversal post-jury, and by the observation that the rank order of preferences for the control group who did not participate in the jury changed pre- to post the jury, as did the juror preferences.

We did find some evidence that the information and deliberation afforded through participation in a CJ may increase the consistency of decision-making for jurors. Decision-making became more consistent (less random) for jurors after the jury, whereas it became less consistent (more random) for controls. The finding of increased choice consistency after the provision of information and deliberation is aligned with the findings of Veldjwick et al. who reported that choice consistency as measured by scale effects in the DCE was higher for participants in a DCE who were given “time to think” before completing the choice tasksCitation35. However, this contrasts with the observation that jurors were less likely to give a consistent response to the repeat choice question than controls after the jury. The lower level of consistency in the jurors could potentially be explained by an increased understanding of the complexity of priority setting and consequently a more nuanced preferences of CJ participants; this could be the case especially if the utility of choice alternatives in the choice set were balanced and therefore choice probabilities of the alternatives were close to 50/50. It is possible that an explanation for this latter observation is that the jurors may have been fatigued when they completed the DCE survey, which was administered immediately following the jury. Regardless, any improvement in consistency that might be attributed to participating in a jury only had a minor impact on priorities.

Previous studies have reported that the provision of information and deliberation impacts on preferences for priority settingCitation6,Citation19, but others have reported that the views of participants in a deliberative panel were largely similar before and after the panelCitation36. It might be that any impact of information and deliberation on preferences is context-specific. Abelson et al. reported an impact of face-to-face deliberation on priority rankings for two priority health concerns (teen pregnancy and mental illness) but did not observe the same trend for rankings related to scenarios involving determinants of health leading them to suggest the characteristics of the issue under consideration might affect the deliberation processCitation19. Therefore, the subtle changes in prioritization that were observed in our study might not have impacted the final prioritization decision to a substantial extent, but could have significant implications in more sensitive topics. Interestingly, Abelson et al. also noted that the greater opportunity for deliberation afforded by the face-to-face method had a greater impact on priorities than that afforded by an alternative telephone methodCitation19. Dolan et al. reported that respondents who initially wanted to give lower priority to smokers, heavy drinkers and illegal drug users no longer wanted to discriminate against these groups after discussionCitation6. Thus, it’s possible that in different and perhaps more contentious or divisive issues, the provision of information and deliberation might have a more substantial impact on prioritization preferences. It may also be relevant that we asked jury and DCE participants to make recommendations or choices related to prioritization at a policy rather than bedside level. The choice context they were presented with related to a group of unnamed, hypothetical patients, we did not present case studies with pseudo-anonymized individual patients. It’s not clear if our findings would be the same had we framed our choices to relate to bedside prioritization decisions related to individual patientsCitation24,Citation37.

In considering how to implement these two approaches the data here provide two insights. First, for the CJ, expert witnesses presented opposing views which is a requirement of a good jury processCitation26. Hence, the pattern of differentiation of juror preferences and reversal of priority rank assigned to one of the criteria may be indicative of jurors being swayed more one way or the other according to their interpretation of the evidence presentedCitation15. A different jury, with different experts, might lead to different results. The Brisbane and Adelaide juries had the same facilitator, but different experts presented evidence. The selection of expert views and perspectives presented to the jury may have an impact on recommendations. Second, the consistency between juror and public preferences (measured by rank of prioritization criteria) at baseline reinforces the importance of a robust selection process, to ensure participants in a jury reflect the diversity of the public and respondents to a DCE are representative of the public by key characteristics that are relevant to the decision context. Although there were only small differences in priority ranks across samples, we also observed small differences between the recommendations made by the two juries held using different recruitment methods, duration, and in different locations, suggesting that it may be how the CJ and DCE methods are applied and in whom that are most important, and not necessarily which method is used to seek public input.

What do our findings mean for how researchers and policy makers can best derive evidence on preferences for prioritization from the public, to inform health policy decision-making and resource allocation decisions? The different resource implications of eliciting preferences through different approaches are likely to be a consideration in choosing between methods, particularly if the prioritization implications from the two approaches are consistent. While they are substantially smaller in size, the juries are fairly resource intensive to conduct and for a national issue it might be necessary to conduct more than one jury in different localities to ensure representation, which would be costly. Whilst DCEs also require resources to develop and implement the survey and appropriate expertise to design the survey and analyze the data, they are likely to achieve national representation at a lower cost than juries. The current study suggests that using a combination of methods would provide little more insight that one method alone. Nevertheless, the value of CJs may be more than getting rankings of preferences and priorities. CJs can inform decision processes as well as actual decisions but can also offer engagement in an ongoing decision-making processCitation38. Moreover, the public might view the CJ process as more legitimate than a relatively uninformed DCE approach, potentially leading to greater public buy in. Although the CJ is small, if its participants are carefully selected so as to be representative of the public then the comprehensive CJ process may mean that the wider public may feel satisfied that the issue has been investigated in depth, deliberated and conclusions reached. As such, there could be intrinsic value in utilizing deliberative methods such as the CJ above and beyond their instrumental findings.

Compositional approaches such as multicriteria decision analysis (MCDA) are of growing interest in priority setting contexts including health technology assessmentCitation39,Citation40. Although we didn’t include a compositional approach as part of our study, future work could also consider combining the methods to ensure rigor particularly if addressing a contentious policy question. If a joint method is used, we would advocate undertaking a CJ on the topic first and using the CJ recommendations to inform the criteria to be included in a DCE undertaken by a large, representative sample of the public and potentially also the jury members. In our case, this would have resulted in a reduced number of DCE attributes being required, which would minimize any cognitive burden associated with the DCE and reduce the sample size required to achieve precise estimates (lowering the costs of undertaking the DCE). The CJ could then be reconvened and the juror and public DCE findings presented to them to “sense check” the implications, and to then make final recommendations for policy.

Having a single content issue is both a strength of this study in terms of providing consistency, and also a weakness. We don’t know if the relationship observed for priorities between informed jurors and the wider public might be different for topics for example with more extreme public views and/or where less content expertise is required. Similarly, in this study we asked about prioritization of access for different “classes” of individuals within the same health condition, not about priority given to different types of services. Repeating this work in different contexts would develop our understanding of whether findings hold more widely across other policy issues.

The limitations of this study include the response to recruitment efforts, which could be considered to be modest, and the selection process used to allocate participants between the juror and control group, which was not random. There were some apparent disparities between groups in their sociodemographic characteristics and overweight/obesity levels. Therefore, the control sample should be viewed as a convenience sample and there may be some self-selection bias evident. For example, the greater proportions of overweight and obese participants in the CJ group than in the control group may affect that groups’ responses. Moreover, the combination of the two jury groups (Brisbane and Adelaide) into a single group for the analysis assumes the two juries would have a similar influence on preferences, which given the difference in the jury duration and structure, may not be the case. This may limit the findings related to the comparison of control and juror preferences for our first two research questions. Nevertheless, utilizing a control sample to undertake the DCE both before and after the jury has provided some insights to the potential impact of the jury process on the consistency of preferences in particular. The sample size for jurors and controls also limited our ability to quantitatively compare preferences across groups. We were unable to validly test for any impact of information and deliberation on the strength of preference (as opposed to the rank) for different prioritization criteria in this sample size. In addition, the public sample completed the DCE within 6 months of the CJs; the possibility that societal preferences related to surgical management of obesity may have shifted in that time should be considered when comparing the public and juror preferences.

The DCE design assumed there were no interactions between attributes, including between the “severity” of obesity and “comorbidities”. If this assumption does not hold, it might lead to a bias on the preference parameters estimated by the DCE model. This could potentially explain the minor differences in rank order observed between the post-jury DCE and Brisbane jury recommendations and between the public DCE and both jury recommendations, but should not limit the comparison between different DCE samples. It is also possible that completion of the DCE prior to the jury may have impacted the discussion and deliberation during the jury, for example by increasing the relative importance of the DCE attributes, potentially leading to jury recommendations that were more aligned with the DCE attributes than they may otherwise have been. If this is the case, it is possible that the recommendations made by a jury who have not completed a DCE on the topic before their deliberations might be less aligned with the DCE findings.

Preferences within the control group appeared to change from “Control PRE” to “Control POST” even though they did not receive the jury intervention, such that the control group placed a higher priority on managing very severe obesity. The study did not provide any insight to why this might have occurred. However, it is possible that this might be explained by a “learning effect” (i.e. repeated exposure to the questions achieves stability in responses). In addition, respondents in the control group have had longer to think about the issue before responding to the next survey and might have undertaken their own background research such as talking with family members and colleagues or web searches – this might have influenced their responses to the subsequent DCE.

To conclude, being informed and undertaking deliberation had little impact on the criteria that were considered to be relevant for prioritizing access to bariatric surgery, but may impact to a small extent on the relative importance of those criteria and increase consistency of decision-making. Citizen juries may clarify underlying rationale but may not necessarily provide substantially different prioritization recommendations to a DCE.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was undertaken with the support of funding from an Australian Research Council Linkage Grant (#LP100200446), and Partner Organisations Queensland Health (Metro South Hospitals and Health Service), Southern Adelaide Local Health Network Inc, and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK).

Declaration of financial/other interests

JAW was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration East of England. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

RK was supported by a grant from the Australian Centre for Health Services Innovation (PostGraduate Scholarship PHD-000432, funded round 1–2013, top up granted 2014). PL is supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care South London at King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. PS was the recipient of an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Research Fellowship 2018-22 (#1136923).

This study was presented at a symposium in Glasgow sponsored by the Welcome Trust.

Author contributions

JAW, PL, JR, AW, EK, PB, KC, PAS conceived of and advised on the parent CJ and DCE study. JAW, JR, PAS, KR developed the DCE and guided data collection. JAW and PL conceptualized the research focus and approach of this paper. JAW undertook data analysis and interpretation, and drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to data interpretation, reviewed the draft manuscript, contributed academic content, and approved the final version. JAW and PS act as overall guarantor for this study.

Previous presentations

The data described in this study were presented at a symposium organised by Glasgow Caledonian University in 2019.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (255.5 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the project team and partners for support with data collection. The authors gratefully acknowledge the contribution of the jurors, expert witnesses, and members of the public, who participated in this study.

References

- Caddy J, Vergez C. Citizens as partners: information, consultation and public participation in policy-making. Paris: organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development; 2001.

- Whitty JA, Lancsar E, Rixon K, et al. A systematic review of stated preference studies reporting public preferences for healthcare priority setting. Patient. 2014;7(4):365–386. doi: 10.1007/s40271-014-0063-2.

- Hougaard JL, Tjur T, Osterdal LP. On the meaningfulness of testing preference axioms in stated preference discrete choice experiments. Eur J Health Econ. 2012;13(4):409–417. doi: 10.1007/s10198-011-0312-4.

- Whitty JA, Burton P, Kendall E, et al. Harnessing the potential to quantify public preferences for healthcare priorities through citizens’ juries. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2014;3(2):57–62. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2014.61.

- Shiell A, Seymour J, Hawe P, et al. Are preferences over health states complete? [research support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Health Econ. 2000;9(1):47–55. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1050(200001)9:1<47::AID-HEC485>3.0.CO;2-L.

- Dolan P, Cookson R, Ferguson B. Effect of discussion and deliberation on the public’s views of priority setting in health care: focus group study [empirical. BMJ. 1999;318(7188):916–919.] doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7188.916.

- McTaggart-Cowan H. Elicitation of informed general population health state utility values: a review of the literature [research support, Non-U.S. Gov’t review]. Value Health. 2011;14(8):1153–1157. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2011.05.046.

- Scuffham PA, Whitty JA, Mitchell A, et al. The use of QALY weights for QALY calculations: a review of industry submissions requesting listing on the Australian pharmaceutical benefits scheme 2002–4. Pharmacoeconomics. 2008;26(4):297–310. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200826040-00003.

- Jefferso Center. Citizens jury handbook. The Jefferson center for new democratic processes. Minnesota: Jefferso Center; 2004.

- Mooney GA. Handbook on citizens’ juries with particular reference to health care. 2010. Available from: https://newdemocracy.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/docs_researchpapers_Mooney_CJ_BookJanuary2010.pdf

- Mooney GH, Blackwell SH. Whose health service is it anyway? Community values in healthcare. Med J Aust. 2004;180(2):76–78. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2004.tb05804.x.

- Menon D, Stafinski T. Engaging the public in priority-setting for health technology assessment: findings from a citizens’ Jury. Health Expect. 2008;11(3):282–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2008.00501.x.

- Iredale R, Longley M, Thomas C, et al. What choices should we be able to make about designer babies? A citizens’ jury of young people in South Wales. Health Expect. 2006;9(3):207–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2006.00387.x.

- Paul C, Nicholls R, Priest P, et al. Making policy decisions about population screening for breast cancer: the role of citizens’ deliberation. Health Policy. 2008;85(3):314–320. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2007.08.007.

- The Jefferson Center. Citizens Jury handbook: the Jefferson center for new democratic processes. 2004 [cited 2011 Nov 21]. http://jefferson-center.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/Citizen-Jury-Handbook.pdf

- Elwyn G, Miron-Shatz T. Deliberation before determination: the definition and evaluation of good decision making. Health Expect. 2010;13(2):139–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2009.00572.x.

- Robinson S, Bryan S. Does the process of deliberation change individuals’ health state valuations? An exploratory study using the person trade-off technique [research support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Value Health. 2013;16(5):806–813. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2013.03.1633.

- Witt J, Elwyn G, Wood F, et al. Decision making and coping in healthcare: the coping in deliberation (CODE) framework [review]. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;88(2):256–261. Augdoi: 10.1016/j.pec.2012.03.002.

- Abelson J, Eyles J, McLeod CB, et al. Does deliberation make a difference? Results from a citizens panel study of health goals priority setting. Health Policy. 2003;66(1):95–106. Octdoi: 10.1016/s0168-8510(03)00048-4.

- Scuffham PA, Ratcliffe J, Kendall E, et al. Engaging the public in healthcare decision-making: quantifying preferences for healthcare through citizens’ juries. BMJ Open. 2014;4(5):e005437. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005437.

- Colquitt JL, Pickett K, Loveman E, et al. Surgery for weight loss in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014(8):CD003641. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003641.pub4.

- Korda RJ, Joshy G, Jorm LR, et al. Inequalities in bariatric surgery in Australia: findings from 49,364 obese participants in a prospective cohort study [research support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Med J Aust. 2012;197(11):631–636. Dec 10doi: 10.5694/mja12.11035.

- Whitty JA, Ratcliffe J, Kendall E, et al. Prioritising patients for bariatric surgery: building public preferences from a discrete choice experiment into public policy. BMJ Open. 2015;5(10):e008919. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008919.

- Persson E, Andersson D, Back L, et al. Discrepancy between health care rationing at the bedside and policy level. Med Decis Making. 2018;38(7):881–887. Octdoi: 10.1177/0272989X18793637.

- Scuffham PA, Krinks R, Chalkidou K, et al. Recommendations from two citizens’ juries on the surgical management of obesity. Obes Surg. 2018;28(6):1745–1752. Jundoi: 10.1007/s11695-017-3089-4.

- Abelson J, Forest PG, Eyles J, et al. Deliberations about deliberative methods: issues in the design and evaluation of public participation processes. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(2):239–251. Juldoi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00343-x.

- Thomas R, Sims R, Degeling C, et al. CJCheck stage 1: development and testing of a checklist for reporting community juries – Delphi process and analysis of studies published in 1996–2015. Health Expect. 2017;20(4):626–637. doi: 10.1111/hex.12493.

- Johnson FR, Lancsar E, Marshall D, et al. Constructing experimental designs for discrete-choice experiments: report of the ISPOR conjoint analysis experimental design good research PracticesTask force. Value Health. 2013;16(1):3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2012.08.2223.

- Marshall D, Bridges JFP, Hauber B, et al. Conjoint analysis applications in health – How are studies being designed and reported? [review]. Patient. 2010;3(4):249–256. doi: 10.2165/11539650-000000000-00000.

- Littlejohns P, Rawlins M. Patients, the public and priorities in healthcare. Oxford: Radcliffe Publishing Ltd.; 2009.

- Rawlins MD. Pharmacopolitics and deliberative democracy [discussion]. Clin Med. 2005;5(5):471–475. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.5-5-471.

- Weale A, Kieslich K, Littlejohns P, et al. Introduction: priority setting, equitable access and public involvement in health care. J Health Organ Manag. 2016;30(5):736–750. doi: 10.1108/JHOM-03-2016-0036.

- Daniels N. Accountability for reasonableness: establishing a fair process for priority setting is easier than agreeing on principles. Br Med J. 2000;321(7272):1300–1301. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7272.1300.

- Bridges JF, Hauber AB, Marshall D, et al. Conjoint analysis applications in health-a checklist: a report of the ISPOR good research practices for conjoint analysis task force. Value Health. 2011;14(4):403–413. Jundoi: 10.1016/j.jval.2010.11.013.

- Veldwijk J, Johansson JV, Donkers B, et al. Mimicking real-life decision making in health: allowing respondents time to think in a discrete choice experiment. Value Health. 2020;23(7):945–952. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2020.02.014.

- Reckers-Droog V, Jansen M, Bijlmakers L, et al. How does participating in a deliberative citizens panel on healthcare priority setting influence the views of participants? Health Policy. 2020;124(2):143–151. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2019.11.011.

- Colby H, DeWitt J, Chapman GB. Grouping promotes equality: the effect of recipient grouping on allocation of limited medical resources. Psychol Sci. 2015;26(7):1084–1089. doi: 10.1177/0956797615583978.

- Boulianne S, Loptson K, Kahane D. Citizen panels and opinion polls: convergence and divergence in policy preferences. J Public Delib. 2018;14(1):4.

- Baltussen R, Marsh K, Thokala P, et al. Multicriteria decision analysis to support health technology assessment agencies: benefits, limitations, and the way forward. Value Health. 2019;22(11):1283–1288. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2019.06.014.

- Thokala P, Duenas A. Multiple criteria decision analysis for health technology assessment. Value Health. 2012;15(8):1172–1181. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2012.06.015.