?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Background

Treatment-resistant depression (TRD) in major depressive disorder (MDD) is most commonly defined as the failure to respond to at least two antidepressant (AD) treatments of adequate duration and adherence. While the health care utilization (RU) and costs of patients with MDD are well documented, little is known about patients with TRD. Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine the direct medical RU of complex therapy pathways and to analyze the total cost-of-illness and the burden-of-disease in Austria.

Methods

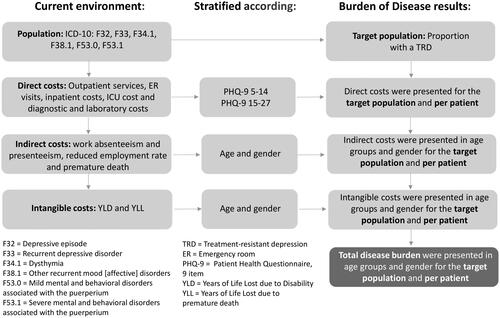

In order to quantify the cost-of-illness and burden-of-disease of TRD, the analysis was designed with two steps. First, RU data were collected through an extensive survey of Austrian experts and a systematic literature review. Second, direct, indirect, and intangible costs were calculated using the micro-costing method. The results are presented per patient and based on a patient flow for the entire cohort of TRD patients.

Results

In Austria, the derived prevalence of TRD is 43,732 patients or 583 per 100,000 population. For 2021, the annual direct costs of TRD were estimated at 345.0 million €. At 684.7 million €, the estimated indirect costs were higher than the direct costs, representing 66.5% of the total cost-of-illness. The average annual cost per TRD patient is 23,547 €, of which direct costs are 7,890 €. Adding the years lived with a disability to the years lost due to premature death attributed to TRD resulted in a total of 29,884 disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for the Austrian society.

Conclusion

Although TRD accounts for only 0.7% (range: 0.6%–1%) of the total health care budget, it represents a significant burden-of-disease. In addition, TRD is associated with a high level of lost productivity in the Austrian economy. These findings support efforts to prioritize TRD as a focus area to achieve health-related goals.

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a major public health concern worldwide. The 12-month prevalence of depression based on clinical interviews is 6.9% in EuropeCitation1 and 8.6% in the USCitation2. The administrative prevalence of depressive disorders, derived from health insurance claims data is generally higher than the prevalence derived from clinical epidemiologic studies because it includes non-specific depressive disorders and remitted relapsing depressive disorders. In Germany in 2017, the administrative prevalence of depressive disorders in persons age 15 years and older was 15.7%, a sharp increase from the prevalence rate of 12.5% in 2009Citation3. Due to the similar demographic and ethnic composition of the German and Austrian populations, similar developments can be expected in Austria. Among patients receiving antidepressant treatment of adequate duration and dosage, approximately one third suffer from treatment-resistant depression (TRD)Citation4–6. Treatment resistance is defined by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) as a major depressive episode that fails to respond to treatment with two or more different antidepressants at an adequate dose and duration, and with adequate adherenceCitation7. Treatment resistance is also common and is evident in clinical trials of various antidepressants, with one third to one half of patients failing to respond after several weeks of treatmentCitation8. The large US STAR*D study found that more than half of all patients recruited from primary care and mental health clinics did not achieve remission after first-line antidepressant treatment, and 33% did not achieve remission after four courses of short-term treatmentCitation9. An European study (GSRD) found that 50.7% of depressed patients recruited from specialist referral centers were considered treatment-resistant after two consecutive courses of treatment with antidepressantsCitation10.

Globally, unipolar depressive disorders are the leading cause of years of life lost due to disability (YLD) in World Health Organization (WHO) member states, accounting for 5.6% of total YLD from all diseasesCitation11. The total economic burden of MDD in the US is estimated to exceed 200 billion $Citation12. The classification of TRD had a clinically meaningful and statistically significant association with increased direct costs, employment-related costs, and health care resource utilization. All else being equal, the classification of TRD was associated with 29.3% higher medical expenditures (p < 0.001) compared to patients who did not meet the study definition of TRDCitation13. Lack of treatment stability or pharmacotherapy cycles and switching were associated with increased direct costs. In addition, significant indirect costs, including lost productivity due to illness, sick leave, and early retirement, have been reported in patients with MDDCitation14. Notably, almost half of the total economic burden associated with medically treated MDD (47.2%) is attributable to one-third of patients with TRD (30.9%)Citation15. In addition, a systematic review demonstrated a devastating impact of TRD on health-related quality of life (HRQoL). Self-rated scores were 0.26–0.41 points lower in the adult population with TRD compared to MDD in remission or responding to treatmentCitation16.

Analyzing the disease burden of TRD – a subset of MDD – is a relevant question for several reasons:

First, the epidemiology of TRD is not as well studied and characterized due to the heterogeneity of criteria and methods and the paucity of epidemiologic studies. However, it is estimated that more than one-third of treated patients with MDD will progress to TRDCitation8,Citation9. In addition, most of the data have been generated in the US.

Second, patients with TRD do not respond to traditional and first-line pharmacotherapies, making it challenging to find an appropriate treatment. There are several definitions and staging models of TRD and no consensus has been reached so far. However, common to all models is an inadequate response to at least two trials of antidepressant pharmacotherapyCitation17.

Third, because of the previous two points, the burden-of-disease is difficult to estimate and cannot be extrapolated from MDD. Therefore, the aim is first to determine the direct medical resource utilization and costs resulting from complex treatment pathways in Austria. Furthermore, the total burden-of-disease burden for Austria will be determined, which consists of the following components:

Direct costs include all clinical care services within the health care system.

Indirect costs include costs due to the absence from work (absenteeism and presenteeism), costs due to reduced working capacity and costs due to premature death.

Intangible costs specifically measure the “burden” of Years of Life Lost due to Disability or morbidity and the Years of Life Lost due to premature death in non-monetary units.

Method

Accurate knowledge of the cost-of-illness (CoI) and the burden-of-disease (BoD) is essential and helps formulate and prioritize health care interventions and ultimately allocate health care resources according to budget constraints. As a result, higher levels of efficiency can be achievedCitation18.

This analysis consists of two components. First, the monetary valuation of disease costs (direct and indirect) using a CoI approach. In conducting a CoI study, the costs caused by a disease must be recognized, identified, listed, measured, and monetized. In this sense, a CoI study typically includes a metric to measure “health loss” in terms of resource use and costs that could be avoided if the disease was eradicated. On the other hand, a quantification of the disease burden associated with the cost-of-illness is based on a BoD approach. In particular, the BoD approach measures the “burden-of-disease” expressed in years of life lost (YLL) due to premature death and years of life lost due to disability or morbidity (YLD). These two categories form a measure of “intangible costs” called total DALYs (disability-adjusted life years)Citation18. Burden-of-disease or the intangible costs (namely pain and suffering) were not monetized using WTP functions that include motivations related to lost production, to avoid double-countingCitation19.

Based on a systematic literature review (SLR) conducted in the first step, it was not possible to collect resource utilization (RU) data to determine the direct costs of TRD in Austria because the data come from non-comparable health care systems, show substantial differences in treatment patterns or are derived from patients with general MDD that cannot be extrapolated to TRD; i.e. the knockout criteria will apply due to clinical implausibilityCitation20.

For this reason, it was necessary to develop a specific analytical two-step design for the present CoI and BoD study. The first step was to collect RU data through an extensive survey of Austrian TRD experts to collect medical RU. The necessary data for the calculation of indirect and intangible costs were determined with the help of an SLR, as the experts could not make any statements about this. Detailed information can be found in the Appendix (Supplementary material). In a second step, a CoI and BoD model was developed. The detailed procedure is described below.

Expert survey and SLR

A key element in determining the direct costs associated with the treatment of TRD patients was an online survey of local psychiatric specialists to assess the TRD treatment algorithm with pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment options and the RU of this patient group.

The survey was originally developed to generate Austrian data on the treatment algorithm and health care resource use of TRD patients as a part of a larger cost-effectiveness analysis in TRD conducted on behalf of, and funded by, Janssen-Cilag-Pharma GmbH. A targeted literature search in December 2019 did not identify any Austrian clinical or public health studies with representative data on this patient group. Furthermore, as the authors did not have access to electronic health records and/or patient records, conducting a representative expert survey was considered the most appropriate means to generate these data. Since TRD patients are primarily treated as inpatients during an acute depressive episode, senior physicians at psychiatric departments of Austrian hospitals were contacted for the survey. The largest tertiary centers in Austria with experience in the treatment of TRD were contacted by e-mail, taking into account geographic representativeness. Due to the additional organizational workload in the centers during the pandemic situation at that time, the response was very limited. At the time of the data cut of the first survey round at the end of April 2020, four experts had agreed to participate in the survey. Three additional experts participated in a second round of the survey between March and April 2021.

A total of seven experts from six psychiatric units out of a total of 28 psychiatric units specialized in the treatment of adult patients with mental disorders participated in the survey. The facilities represented in the expert survey have an average bed capacity of 122 beds and a total bed capacity of 732 beds for inpatient treatment of psychiatric patients. In relation to the average available total bed capacity of 4,456 beds in psychiatric departments in Austria in 2021, the represented facilities account for 16.4% of the available inpatient treatment capacity in Austria. An analysis of the TRD-associated RU from the first phase of the survey (three participants) was presented at the ISPOR Europe 2020 conferenceCitation21.

The online survey was created using the LimeSurvey software (Lime Survey: An Open-Source survey tool/LimeSurvey GmbH, Hamburg, Germany). The questionnaire consisted of 19 sections with a total of 51 items. Depending on the topic, open-ended, closed-ended, constant-sum, or multiple-choice questions were used. Sections 1–3 dealt with the TRD treatment algorithm in general. Sections 4–15 addressed the use of pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment options in different phases (acute phase, maintenance therapy during response and remission phases, relapse prevention during complete recovery) and lines of treatment. The following pharmacological treatment options were considered: Augmentation therapy with oral antidepressants and lithium (AUG-LI), augmentation therapy with oral antidepressants and antipsychotics (AUG-AP), combination therapy with antidepressants of different pharmacologicalal classes (CT), dose escalation of the current antidepressant (DE), and switching to an antidepressant of a different pharmacologicalal class (SW). In addition, the use of the following non-pharmacologicalal treatment options was queried: Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (RTMS), vagus nerve stimulation (VNS), and deep brain stimulation (DBS). Sections 16–18 addressed the RU in health states defined by the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9) score (15–27: moderately severe to severe symptoms – acute depressive episode, 5–14: mild to moderate symptoms – response). Section 19 included questions about the work situation of TRD patients in Austria.

Participating experts received personalized and anonymized access codes to take part in the survey. Questions regarding the therapy algorithm were designed as mandatory questions. Answers to a multiple-choice question on the clinical relevance of pharmacological therapies (Treatment algorithm III – question 4; Supplementary material, Appendix) activated the query of relevant optional question modules (Pharmacological therapies I-VI; Supplementary material, Appendix). When clinically relevant question modules were activated, experts had to indicate at least three individual drugs per treatment strategy (exception: lithium) with the corresponding patient proportion and dosage applied. Questions about the RU in the outpatient setting (emergency room, outpatient clinic, general practitioner, psychiatrist, psychotherapy) and in the inpatient setting (normal ward, intensive care unit) according to health status were defined as mandatory questions. The experts were able to determine the use of up to ten diagnostic measures relevant to clinical practice per health state.

Arithmetic means were calculated from the survey participants’ responses to determine the average number and percentage composition of pharmacological treatment lines, as well as the mean RU per health state. Since the questions on the treatment algorithm and RU in the outpatient and inpatient settings were defined as mandatory, there were no missing values. Responses to the optional open-ended questions on pharmacological therapies and diagnostic measures (Pharmacological therapies I–VI; Resource use I: questions 30 and 31; Resource use II: questions 34 and 35; Supplementary material, Appendix) were included in the determination of RU if at least three clinical experts, or 50% of the clinical experts if fewer than five individual records were available for the question, mentioned the same drug or diagnostic measure. However, it was not possible to collect representative cross-sectional data for non-pharmacological treatments and data on absenteeism and presenteeism, as only a minority of clinical experts could provide assessments on these. The items of the expert survey used to generate the data for this study and the summarized results of the questionnaire with the number of responses given are included in the Appendix (Supplementary material). The resulting quantity structures are linked to Austrian cost data to determine the annual treatment costs and disease management costs per health state.

The SLR was conducted in December 2019 according to the PRISMA guidelines for reporting systematic reviewsCitation22. First, the SLR inclusion criteria were defined, and comprehensive and efficient search strategies based on Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) were developed for the scientific bibliographic databases MEDLINE and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL). This was supplemented by a search of Google Scholar and a hand search of the websites of medical specialty societies, health authorities, public and private health insurance associations, and HTA agencies. Details of inclusion criteria, search strategies, the literature flow, and the included literature are provided in the Appendix (Supplementary material).

Cost-of-illness and burden-of-disease analysis

We used a prevalence-based approach to estimate the economic and disease burden of TRD over one year to draw decision-makers’ attention to a condition whose burden has been somewhat underestimated. Prevalence-based studies estimate the number of cases, deaths, and hospitalizations attributable to TRD in a given year and then estimate the costs that result from those cases, deaths or hospitalizations (plus other costs such as absence from work)Citation19.

The target population with a diagnosed TRD was derived based on a patient flow. The total number of patients with depression (ICD-10: F32 = depressive episode, F33 = recurrent depressive disorder, F34.1 = dysthymia) and epidemiological data from a SLR were used to determine the target population with TRD (see section Study Population).

The PHQ was used as a measure of severity, corresponding to specific DSM-IV diagnoses. The score ranges from 0 to 27. Major depression is diagnosed when 5 or more of the 9 depressive symptom criteria have been present for at least “more than half the days” in the past 2 weeks, and 1 of the symptoms is depressed mood or anhedoniaCitation23. For our analysis the PHQ-9 score was categorized as follows: 5–14 for mild to moderate depression, and 15–27 for moderately severe to severe depression.

To collect costs, we used a bottom-up micro-costing approach in which cost estimates were stratified into two steps. The first step was to quantify the health care inputs used, which involved identifying highly detailed resource use items, and the second step was to estimate the unit cost of the inputs. The RU data collected for each individual patient were then multiplied by unit cost to estimate the expenditureCitation24. The total cost-of-illness was then calculated by multiplying expenditure per patient by the number of TRD patients. The required quantity structure for direct costs was determined on the basis of an expert survey, while the required quantities for indirect costs and the intangible disease burden were extracted from a SLR.

A deterministic one-way sensitivity analysis was performed to assess how variations of individual input parameter values affect the outputs, specifically, the total cost-of-illness and the DALYs, and thus to assess the robustness of our findings. Input ranges for sensitivity analysis were obtained by adding or subtracting percentage values to or from the baseline estimates (±20% for costs, 95%-CI or alternatively ±10% for clinical input data, or ranges from the SLR for epidemiological data).

Results are presented from the societal perspective. Costs refer to the year 2021. Calculations were performed using Microsoft® Excel® for Microsoft 365 MSO (version 2010). An overview of the model is displayed in .

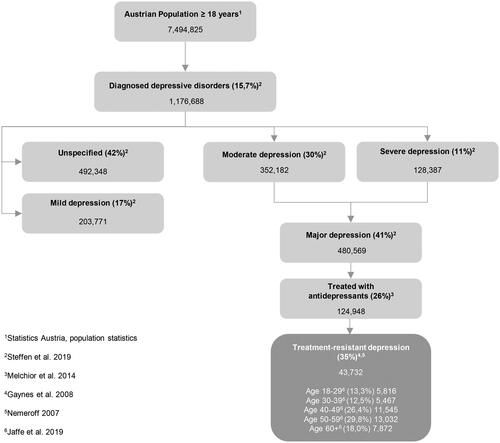

Study population

As no 12-month prevalence of diagnosed depression stratified by severity is available for Austria, administrative 12-month prevalence data from Germany were usedCitation3. Because of the comparable demographic and ethnical composition, it can be assumed that the German prevalence data are transferable to Austria. On this basis, it is estimated that 1,176,688 adults are suffering from a diagnosed depression. In the publication by Steffen et al. (2019)Citation3, it is reported that approximately 41% of patients diagnosed with depression had a moderate or severe depression. This estimate was applied to Austria resulting in 480,569 affected individuals. An analysis by the Bertelsmann Foundation, which evaluated insurance data from 84 German company and guild health insurance funds for the years 2008–2011, reported that approximately 26% of patients diagnosed with depression (corresponding to 124,948 patients in Austria) received antidepressant therapy at an adequate dose and durationCitation25. Data from the large real-world STAR*D study indicate that approximately 35% of patients do not have an adequate response to at least two antidepressants from different pharmacological classes, when given in sufficient doses and durationCitation26,Citation27. This corresponds to an estimated 43,732 TRD patients in Austria, of whom 29,607 are female (67.7%) and 14,125 are male (see ).

The risk of suicide during an acute depressive episode was derived from a published SLR that evaluated suicide rates in depressed patients who did not respond to at least two different antidepressant therapies. Thirty studies assessed suicidality in 32 TRD samples. The overall incidence of completed suicide was estimated to be 0.47 per 100 patient-years (95% CI: 0.22–1.00)Citation28. This incidence rate was applied to patients with a PHQ-9 score of 15–27. For patients with a PHQ-9 score between 5 and 14, we assumed that the suicide incidence rate was half of that estimated for the higher score group.

Costs of illness

Direct costs

The following direct medical cost factors are considered for the treatment of TRD patients in Austria: Treatment costs, outpatient costs, inpatient costs and costs for TRD-related diagnostic measures ().

Treatment costs

The annual treatment costs of an average TRD patient in Austria are calculated as the weighted mean of the treatment costs of AUG-AP, AUG-LI, CT, DE and SW treatments. As the expert survey did not provide representative results on the use of non-pharmacological treatments, it is not possible to determine the costs of non-pharmacological treatments. The annual costs for pharmacological regimens are based on the patient shares of the active ingredients used, the mean daily dose of these active ingredients and the respective drug costs. These costs are weighted with the estimated TRD patient shares in Austria for three consecutive lines of therapy, derived from the results of the expert survey (Supplementary material, Appendix), to determine the annual treatment costs for an average TRD patient.

Outpatient costs

The annual RU of outpatient care for TRD patients per health state is determined from the results of the expert survey (Supplementary material, Appendix) and is combined with Austrian cost data to generate the mean annual outpatient costs for different health states. Direct costs include visits to emergency rooms, outpatient clinics, general practitioners, psychiatrists, and psychotherapists in this category.

Inpatient costs

The percentage of patients affected, the mean number of inpatient stays per year, and the mean length of stay (LOS) per patient and health condition was derived from the results of the expert survey. In addition, the mean percentage of patients treated in an intensive care unit (ICU), the mean annual number of hospitalizations, and the mean LOS of an ICU stay were determined (Supplementary material, Appendix). The mean annual costs for inpatient stays are obtained by multiplying the RU with Austrian Diagnosis-Related Group (DRG) positions.

Costs for TRD-related diagnostic measures

Clinical experts provided through free responses which diagnostic measures are required for the treatment of TRD per health state (Supplementary material, Appendix). The costs of diagnostic procedures for TRD patients were calculated by multiplying the mean proportion of patients affected and the mean frequency of diagnostic procedures per year by the respective unit costs based on Austrian cost data. It is assumed that patients in the health state “PHQ-9 15–27: moderately severe to severe symptoms – acute depressive episode” are treated primarily in an inpatient setting, whereas patients in the health states “PHQ-9 5–14: mild to moderate symptoms – response” are treated in an outpatient setting.

Indirect costs

The term indirect costs refer to productivity losses due to morbidity and mortality, borne by the individual, family, society, or the employer, which are not directly related to the treatment of the disease. If indirect costs are included in addition to direct costs, these cost components must be presented separatelyCitation39.

This analysis considers the following indirect cost components:

Absence from work (sick leave; absenteeism)

Reduced productivity at the workplace (presenteeism)

Costs due to reduced employment rate

Costs due to premature death

The human capital approach was used to monetize indirect costs, as recommended in the Austrian health economic evaluation guidelinesCitation39. According to the human capital approach, wage rates equal the value of marginal revenue generated by an additional worker under full employment. Thus, indirect costs are quantified as:

Absenteeism

To determine the absence from work, data on the proportion of TRD patients who are in employment are required. The extent of the work loss must be quantified for those TRD patients who are employed. The data are obtained for different age cohorts and by gender, as the costs of absenteeism differ between groups.

Based on a SLR, publications containing information on absenteeism in the TRD population were reviewed. For the present calculations, the study by Jaffe et al. (2019)Citation4 was selected. The authors described a TRD population using a retrospective observational study based on the 2017 National Health and Wellness Survey conducted in five European countries (Germany, France, Italy, Spain and the United Kingdom). Demographics and patient characteristics were evaluated for TRD patients compared to respondents without TRD and to the general population using chi-squared tests. Generalized linear models were performed to investigate group differences after adjusting these estimates for confounding factorsCitation4. In this work, it was documented that 39.20% of TRD patients are employedCitation4. Transferred to Austria, this means that 17,143 TRD patients are employed.

The magnitude of productivity loss due to absenteeism is transferred from the German cohort to Austria, as no data are available for Austria. Using the “Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire: General Health”Citation4, a reduction of 35.91% was determined ().

Presenteeism

The term "presenteeism" refers to the practice of coming to work when ill or not feeling well, which is associated with reduced productivity. The data on presenteeism was also taken from the publication of Jaffe et al. (2019)Citation4, which was derived from a German cohort. A reduction of 45.59% was recorded for presenteeism based on the “Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire: General Health”Citation4.

Costs due to reduced employment rate

These indirect cost components comprise the future production that would not been foregone when patients were able to work. The employment rate of TRD patients is significantly reduced compared to the general population. According to Jaffe et al. (2019)Citation4, only 39.2% of TRD population ≥ 18 years are able to work, compared to 72.7% in the Austrian adult populationCitation41. Employment rates of TRD patients are not available for Austria, therefore data from Germany were used. This results in a reduced work capacity of 33.5 percentage points, affecting 14,667 TRD patients.

Costs due to premature death

The indirect costs of premature death due to suicide correspond to the current value of all future production that would have been carried out by the deceased if the patient had survived. In patients with TRD, excess mortality due to committed suicide is evident (see section “Years of Life Lost due to premature death”). The weighted mortality rate is 0.38% or 168 TRD patients after adjusting for future death due to other causes shown in life tables. The indirect costs of premature death were again assessed using the human capital approach up to retirement age. The age distribution of the deceased corresponds to that of the TRD patients. Lost future earnings were discounted with a 3% discount rate.

Burden-of-disease

Due to methodological issues, no monetary valuation of intangible costs was performed to quantify the burden-of-disease; a monetary valuation using WTP functions that include motivations related to lost production, could also lead to double counting because of the simultaneous application of the human capital approach to evaluate indirect costsCitation19. In this study the disability-adjusted life years (DALY) associated with TRD were determined on the basis of physical units. DALYs combine the time lived with a disability and the time lost due to premature death. The years of life lost due to premature death (YLL) are equal to the number of deaths multiplied by the remaining life expectancy at the age at which death occurs prematurely. However, not only mortality, but also the impairment of normal, symptom-free life due to a disease is captured by DALYs and is added up in the measureCitation42. The equation used to estimate the number of DALYs lost by an individual is as followsCitation43:

c: cause, s: sex, a: age, t: time.

P: prevalence, DW: disability weight

N: number of deaths, L: remaining life expectancy at age of death (in years)

Years of life lost due to disability

Estimation of YLDs requires the use of disease-specific weights, or disability coefficients, and is calibrated according to different levels of disease severity. The most recent version of the weights according to severity level was published by Salomon et al. (2015)Citation44. The use of these weights in TRD depends on the distribution of patients by severity. The distribution of TRD patients by severity was derived from a Portuguese Burden-of-Disease study and was transferred to the Austrian situationCitation34.

Years of life lost due to premature death

As mentioned above, the suicide-related mortality risk of TRD patients was taken – as mentioned – from the publication by Bergfeld et al. (2018)Citation28. In addition to the existing age-dependent background mortality rate from Austrian life tables, the suicide-related mortality is added for the duration of an acute depressive episode. In the "response" health state, half of the value of the suicide-related mortality is added to the background mortality rate ().

Table 1. Input data direct costs.

Table 2. Input data indirect costs.

Table 3. Input data intangible costs.

Table 4. Base-case cost-of-illness results.

Results

Costs-of-illness results

In Austria, the derived prevalence of TRD is 43,732 patients or 583 per 100,000 inhabitants. For 2021, the annual direct costs of TRD were estimated at 345.0 million €, with inpatient costs being the most cost-intensive component at 66.6%. At 229.7 million €, the estimated indirect costs were higher than the direct costs, accounting for 66.5% of the total costs-of-illness. Out of 43,732 TRD patients, only 17,143 are still in the work process. This results in a total annual cost attributable to TRD of 1,029.8 million € ().

The average annual cost per TRD patient is 23,547 €, of which direct costs are 7,890 € and indirect costs are 15,657 €. Severity has a significant impact on direct costs. The direct cost per patient with PHQ-9: 5–14 is 2,462 € per year. Patients with PHQ-9: 15–27 show an expenditure of 10,890 €, 68% of these costs are related to inpatient stays. The total cost for patients with TRD in PHQ-9: 5–14 is 13,798 € compared to 30,084 € in the higher severity level PHQ-9:15–27.

Looking at the total costs-of-illness per age group, costs increase with age from 18,290 €per year in the group of 18 to 29-year-olds to 28,759 € in the over 60 year old age group. This is due to rising employment rates and higher earnings with increasing age. Costs due to premature death decrease with age due to the shorter time to retirement.

Women have lower cost-of-illness than men (21,578 € versus 27,674 €), due to lower earnings during their entire working lives. All details are displayed in .

Table 5. Base-case cost-of-illness subgroup results.

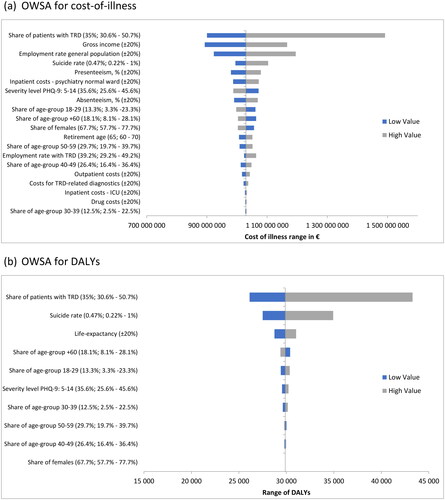

A one-way deterministic sensitivity analysis was carried out to assess the impact of variations in individual parameter assumptions on the total cost-of-illness. Tornado diagrams () were chosen to display the results. Costs range from 892.8 million € to 1,491.7 million €. Results are most sensitive to the number of patients with TRD followed by the gross income and the employment rate of the general population.

Figure 3. Deterministic sensitivity analysis visualized as Tornado plots where each bar represents a one-way sensitivity analysis (OWSA), and the width of bars represents the impact on total cost-of-illness or DALYs lost. The total cost-of-illness or DALYs are plotted on the x-axis. (a) OWSA for cost-of-illness. (b) OWSA for DALYs.

Burden-of-disease results

Using data on prevalence, disability weights, and the TRD severity level, we calculated 24,192 years of life lost due to disability; the majority of which can be attributed to severe depression (18,531 YLD).

YLL are associated with deaths due to suicide. Calculations for Austria estimated 168 cases per year. Based on the age distribution and the number of years lost determined from life expectancy data (33.85 years per person), the result is 5,692 YLL.

Adding the years lived with a disability to the years lost due to premature death attributed to TRD yields a total of 29,884 DALYs for the Austrian society (see ).

Table 6. Disability adjusted life years.

Again, a one-way deterministic sensitivity analysis was performed to quantify the impact on DALYs. The inputs with the greatest influence on the result are number of patients with TRD, the suicide rate and the life expectancy. The results range from 26,127 to 43,290 DALYs ().

Discussion

TRD is one of the biggest clinical challenges in psychiatry. First, this group constitutes about one third of patients with MDDCitation9,Citation26,Citation27. Second, symptoms such as persistent feelings of sadness, sleep disturbance, low energy and thoughts of death or suicide lead to a tremendous loss of quality of life and reduced productivity. In addition, the long-term outcomes of TRD are typically poor. An analysis of data from the STAR*D trial showed that 68% of participants who did not achieve remission experienced "severely impaired" QoL at 1-year follow-up, compared to 13% of those who achieved remissionCitation45. Approximately 30% of the patients will attempt suicide at least once in their lifetimeCitation28. Third, TRD is associated with high direct and indirect costsCitation12,Citation13,Citation46.

We demonstrate that TRD is associated with considerable costs to the health system and society. The annual direct costs associated with TRD amount to 345.0 million €per year. Only 39% of patients are able to work. This results in indirect costs of 684.7 million €per year. Overall, the total cost was 1,029.8 million €. The average annual cost per TRD patient is 23,547 €, of which 7,890 €are direct costs and 15,657 €are indirect costs. Our data are consistent with previous studies. Ivanova et al. (2010)Citation46 have analyzed claims data from 2004 to 2007 for employees aged 18–63 years with one or more inpatient, or two or more outpatient/other MDD diagnoses (ICD-9-CM: 296.2x, 296.3x). Mean direct 2-year costs were significantly higher for probable TRD employees (22,784 $) compared with MDD controls (11,733 $), p < 0.0001. Average indirect costs were also higher for probable TRD employees (12,765 $) compared to MDD controls (6,885 $), p < 0.0001. Costs per patient were comparable to our results for Austria. Another study conducted by OlchanskiCitation13 and colleagues identified patients with chronic MDD and TRD in the PharMetrics patient-centered database. Data between January 2001 and December 2009 were extracted. Based on this, the median health care expenditures per TRD patient per year of enrollment was 8,622 $ compared with 4,547 $ for non-TRD patients (p < 0.001), representing 90% higher costs per yearCitation13. These data also show comparable results to our analysis. In contrast, Gibson et al. (2010)Citation47 calculate 40% higher medical care costs (p <.001) due to TRD compared to depressed patients without TRD based on hospital data between January 2000 and June 2007. The MGH-AD score (antidepressant-only version of the Massachusetts General Hospital clinical staging method for treatment resistance) was associated with an increasing gradient in direct costs. Annual costs for patients with mild TRD (MGH-AD 3.5–4) were 1,530 $ higher than those for non-TRD patients, and costs for patients with complex TRD (MGH-AD > or = 6.5) were 4,425 $ higher than those for non-TRD patients (all p <.001)Citation42. A Belgian retrospective cohort study based on medical records, collected costs for patients diagnosed with MDD who are treatment resistant. One hundred and twenty-five patients were enrolled at nine sites. Results show average annual direct cost of 9,012 €per TRD patient, driven mainly by hospitalization. These results provide a comparable picture to the present analysis. We calculated 7,890 €in direct costs per TRD patient with a 61.7% share of inpatient costs. The work also reports on absences from work. The average costs were only applied on patients in the work process. These amount to an average of 2,878 €per monthCitation48. The results for indirect costs are therefore not comparable. A Spanish retrospective observational-study authored by Pérez-Sola et al. (2021) using data from the BIG-PAC database® included patients classified as TRD and non-TRD. Overall, the mean total cost per MDD patient was 4,148 €, which was higher for TRD than for non-TRD patients (6,096 €vs. 3,846 €; p < 0.001)Citation49. Indirect costs were not reported. An Italian survey-based study was carried on a sample of patients diagnosed with TRD in 2019. A total of 306 observations were collected. The results show an average health care cost of 2,653 €. A national average of 42 days of work lost was estimated resulting in a total cost of 7,140 €per patientCitation50. The results of the survey show significantly lower direct costs compared to Austria, but also compared to the analyses presented above. Indirect costs show a similar picture when only absenteeism and presenteeism are considered.

The main strength of the present burden-of-disease study is that the analysis of direct costs was developed on the basis of Austrian clinical practice, as assessed by a comprehensive expert survey, as resource utilization data should not be compared across countries with substantially different health care systems. Resource utilization and cost data for TRD are primarily available from the US and are therefore not transferable. Unit cost inputs represent 2021 prices and tariffs, no estimations were necessary. For calculation of indirect costs, only European sources were extracted via SLR. Where data from Austria were not available, German data were used in most cases, which is in general transferable to the Austrian health care system.

Among the limitations of this analysis, that must be mentioned when interpreting the results, is that the lack of real-world data, as the evidence is based on expert opinion. Another limitation is the selection bias of experts who participated involved in the survey. The surveyed sample may not be representative of the general population of senior physicians treating TRD patients. However, the current study includes senior physicians working in different geographical regions of Austria, representing facilities, which provide 16.4% of the inpatient treatment capacity in Austria. The opinions of TRD patients and their families were not elicited in this survey. Additional country-specific information on the work situation, informal care, and quality of life of these individuals could thus be collected and is an area for further research. The use of non-pharmacological treatment of TRD could not be representatively assessed. Of the non-pharmacologicalal therapies considered, only ECT and RTMS are more widely used in the treatment of TRD. ECT, in particular, has established itself as the most effective non-pharmacological treatment method and is administered between 1,500 and 2,000 times per year in Austrian patients with schizophrenic and affective disordersCitation32,Citation51. Because of the equipment required and the potential side effects of the treatment, it can be assumed that most of these treatments take place in the inpatient setting and are billed via regular DRG items. Thus, the exclusion of non-pharmacologicalal procedures should not have a major impact on the estimation of the direct costs of TRD treatment. The severity distribution of TRD patients was derived from a Portuguese Burden-of-Disease study and applied to the Austrian situationCitation34. When interpreting these results, the different clinical practice in the two countries should be kept in mind. Due to socioeconomic differences between the two countries, a higher percentage of individuals in Portugal forgo medical treatment for financial reasonsCitation52. In addition, the percentage of institutionalized treatment for mental illnesses is also reported to be higher in PortugalCitation53.

The results show that TRD accounts for only 0.7% (range: 0.6%–1%) of the total health care budget, but has a significant disease burden. Additionally, TRD is associated with a high level of lost productivity in the Austrian economy and society. These results should support decisions to prioritize TRD as an area of focus for future health policy.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This work was funded by Janssen-Cilag Pharma GmbH, Vorgartenstrasse 206B, 1020 Vienna.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

E.W., C.H. and M.G. has received honorarium from Janssen-Cilag Pharma GmbH, Vorgartenstrasse 206B, 1020 Vienna for the submitted work. M.T. and M.Z. have no conflict of interest.

Author contributions

E.W. has substantially contributed to the concept of the study, to the analysis and interpretation of the data, drafted the article, revised the article and finally approved the version to be published. M.T. conducted the expert survey, evaluated the RU data, drafted the article, revised the article, and finally approved the version to be published. M.Z. and M.G. validated and reviewed the data inputs and finally approved the version to be published. C.H. validated the data inputs, drafted the article, revised the article and finally approved the version to be published.

Acknowledgements

None stated.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have received an honorarium from JME for their review work but have no other relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Supplemental Material

Download ()References

- Wittchen HU, Jacobi F, Rehm J, et al. The size and burden of mental disorders and other disorders of the brain in Europe 2010. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;21(9):655–679. PMID: 21896369. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2011.07.018.

- Goodwin RD, Dierker LC, Wu M, et al. Trends in U.S. depression prevalence from 2015 to 2020: the widening treatment gap. Am J Prev Med. 2022;63(5):726–733. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2022.05.014.

- Steffen A, Holstiege J, Akmatov MK, et al. Zeitliche Trends in der Diagnoseprävalenz depressiver Störungen: eine Analyse auf Basis bundesweiter vertragsärztlicher Abrechnungsdaten der Jahre 2009 bis 2017 [Temporal trends in the diagnosis prevalence of depressive disorders: an analysis based on nationwide panel physician billing data from 2009 to 2017]. Berlin (Germany): Zentralinstitut für die kassenärztliche Versorgung in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland (Zi); 2019. Versorgungsatlas.de. 2019;19/05. doi: 10.20364/VA-19.05.German.

- Jaffe DH, Rive B, Denee TR. The humanistic and economic burden of treatment-resistant depression in Europe: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19(1):247. doi: 10.1186/s12888-019-2222-4.

- Amos TB, Tandon N, Lefebvre P, et al. Direct and indirect cost burden and change of employment status in treatment-resistant depression: a matched-cohort study using a US Commercial Claims Database. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79(2):24–32. doi: 10.4088/JCP.17m11725.

- Chow W, Doane MJ, Sheehan J, et al. Economic burden among patients with major depressive disorder: an analysis of healthcare resource use, work productivity, and direct and indirect costs by depression severity. Am J Manag Care. 2019;24(2):1–3.

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Guideline on clinical investigation of medicinal products in the treatment of depression. London (UK): EMA; 30 May 2013. EMA/CHMP/185423/2010 Rev 2.

- Bschor T, Bauer M, Adli M. Chronic and treatment resistant depression: diagnosis and stepwise therapy. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2014;111(45):766–775; quiz 775. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2014.0766.

- Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, et al. Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(11):1905–1917. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.11.1905.

- Souery D, Oswald P, Massat I, et al. Clinical factors associated with treatment resistance in major depressive disorder: results from a European multicenter study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(7):1062–1070. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0713.

- World Health Organization [Internet]. Global health estimates: leading causes of DALYs. Global Health Estimates 2019 summary tables. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; [cited 2023 Jun 12]. Available from: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/mortality-and-global-health-estimates/global-health-estimates-leading-causes-of-dalys

- Greenberg PE, Fournier AA, Sisitsky T, et al. The economic burden of adults with major depressive disorder in the United States (2005 and 2010). J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(2):155–162. doi: 10.4088/JCP.14m09298.

- Olchanski N, McInnis Myers M, Halseth M, et al. The economic burden of treatment-resistant depression. Clin Ther. 2013;35(4):512–522. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2012.09.001.

- Arnaud A, Suthoff E, Tavares RM, et al. The increasing economic burden with additional steps of pharmacotherapy in major depressive disorder. Pharmacoeconomics. 2021;39(6):691–706. doi: 10.1007/s40273-021-01021-w.

- Zhdanava M, Pilon D, Ghelerter I, et al. The prevalence and national burden of treatment-resistant depression and major depressive disorder in the United States. J Clin Psychiatry. 2021;82(2):20m13699. doi: 10.4088/JCP.20m13699.

- Mrazek DA, Hornberger JC, Altar CA, et al. A review of the clinical, economic, and societal burden of treatment-resistant depression: 1996-2013. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(8):977–987. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300059.

- Voineskos D, Daskalakis ZJ, Blumberger DM. Management of treatment-resistant depression: challenges and strategies. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2020;16:221–234. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S198774.

- Jo C. Cost-of-illness studies: concepts, scopes, and methods. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2014;20(4):327–337. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2014.20.4.327.

- Soguel N, van Griethuysen P. Cost of illness and contingent valuation: controlling for the motivations of expressed preferences in an attempt to avoid double counting. Économie publique/Public economics [En ligne], 12 | 2003/1, mis en ligne le 03 janvier 2006, consulté le 28 août 2023. Available from: http://journals.openedition.org/economiepublique/400 doi: 10.4000/economiepublique.400.

- Drummond M, Barbieri M, Cook J, et al. Transferability of economic evaluations across jurisdictions: ISPOR Good Research Practices Task Force report. Value Health. 2009;12(4):409–418. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2008.00489.x.

- Traunfellner M. PMH20 healthcare utilization in patients with treatment-resistant depression (TRD) in Austria. Value Health. 2020;23:S587–S588. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2020.08.1098.

- Page M, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int J Surg. 2021;88:105906. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.105906.

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x.

- Špacírová Z, Epstein D, García-Mochón L, et al. A general framework for classifying costing methods for economic evaluation of health care. Eur J Health Econ. 2020;21(4):529–542. Erratum in: Eur J Health Econ. 2021;22(5):847. doi: 10.1007/s10198-019-01157-9.

- Melchior H, Schulz H, Härter M. Faktencheck Gesundheit – Regionale Unterschiede in der Diagnostik und Behandlung von Depressionen [Health fact check. Regional differences in the diagnosis and treatment of depression]. Gütersloh (Germany): Bertelsmann Stiftung; 2014. German.

- Gaynes BN, Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, et al. The STAR*D study: treating depression in the real world. Cleve Clin J Med. 2008;75(1):57–66. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.75.1.57.

- Nemeroff CB. Prevalence and management of treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(Suppl 8):17–25.

- Bergfeld IO, Mantione M, Figee M, et al. Treatment-resistant depression and suicidality. J Affect Disord. 2018;235:362–367. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.04.016.

- Apoverlag – Warenverzeichnis online [Internet]. Vienna (Austria): Österreichische Apotheker-Verlagsgesellschaft m.b.H. [cited 2021 Jul 12]. Available from: https://warenverzeichnis.apoverlag.at/

- Konstantinidis A, Papageorgiou K, Grohmann R, et al. Increase of antipsychotic medication in depressive inpatients from 2000 to 2007: results from the AMSP International Pharmacovigilance Program. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;15(4):449–457. doi: 10.1017/S1461145711000745.

- IQVIA DPMÖ – Sonderstudie 2019 [Excel file]. Vienna (Austria): IQVIA Austria. 2020 [cited 15.07.2021].

- Kasper S, Erfurth A, Sachs G, et al. Therapieresistente Depression: diagnose und Behandlung, Konsensus-Statement [Treatment-resistant depression: diagnosis and treatment, consensus statement]. Sonderheft JATROS Neurologie & Psychiatrie, 2021 Mar. German.

- World Health Organization [Internet]. WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. ATC/DDD Index 2019. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; [cited 2023 Jun 12]. Available from: https://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index/

- Sousa RD, Gouveia M, Nunes da Silva C, et al. Treatment-resistant depression and major depression with suicide risk – the cost of illness and burden of disease. Front Public Health. 2022;10:898491. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.898491.

- Bundesministerium für Soziales, Gesundheit, Pflege und Konsumentenschutz. Überregionale Auswertung der Dokumentation in landesgesundheitsfondsfinanzierten Krankenanstalten 2019 [Supraregional evaluation of documentation in hospitals financed by state health funds in 2019]. Vienna (Austria): Bundesministerium für Soziales, Gesundheit, Pflege und Konsumentenschutz; January 2021. German.

- Bundesministerium für Soziales, Gesundheit, Pflege und Konsumentenschutz. LKF-Modell 2021 [Austrian DRG model 2021]. Vienna (Austria): Bundesministerium für Soziales, Gesundheit, Pflege und Konsumentenschutz; January 2021. German.

- Österreichische Gesundheitskasse [Internet]. Gesamtvertrag für Ärzte herunterladen [Download general contract for physicians]. Vienna (Austria): Österreichische Gesundheitskasse (ÖGK); [cited 2021 Jul 15]. Available from: https://www.gesundheitskasse.at/cdscontent/?contentid=10007.879101&portal=oegkvpportal German.

- Rechtsinformationssystem des Bundes [Internet]. Verordnung der Wiener Landesregierung über die Festsetzung der Ambulatoriumsbeiträge für die Wiener städtischen Krankenanstalten [Regulation of the Viennese provincial government on the determination of outpatient contributions for the Viennese municipal hospitals]. Vienna (Austria): Bundesministerium für Finanzen; [cited 2021 Jul 15]. Available from: https://www.ris.bka.gv.at/NormDokument.wxe?Abfrage=LrW&Gesetzesnummer=20000627&FassungVom=2021-10-04&Artikel=2&Paragraf=&Anlage=&Uebergangsrecht= German.

- Walter E, Zehetmayr S. Guidelines zur gesundheitsökonomischen Evaluation Konsenspapier [Guidelines for health-economic evaluations in Austria]. Wien Med Wochenschr. 2006;156(23-24):628–632. German. doi: 10.1007/s10354-006-0360-z.

- Statistik Austria. [Internet]. Brutto- und Nettojahreseinkommen nach Altersgruppen 2021 [Gross and net annual income by age group 2021]. Vienna (Austria): Statistik Austria; [cited 2022 Jul 12]. Available from: https://www.statistik.at/fileadmin/pages/333/10_brutto-_und_nettojahreseinkommen_nach_altersgruppen_2021_019351.ods German.

- Statistik Austria [Internet]. Abgestimmte Erwerbsstatistik [Adjusted labor force statistics]. Vienna (Austria): Statistik Austria. 2021 [cited 2022 Sep 12]. Available from: https://www.statistik.at/ueber-uns/erhebungen/registerzaehlung/abgestimmte-erwerbsstatistik

- World Health Organization. Global burden of disease: concepts and methods: 2004 update. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2008.

- Murray CJ. Quantifying the burden of disease: the technical basis for disability-adjusted life years. Bull World Health Organ. 1994;72(3):429–445.

- Salomon JA, Haagsma JA, Davis A, et al. Disability weights for the Global Burden of Disease 2013 study. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3(11):e712–e723. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00069-8.

- IsHak WW, Mirocha J, James D, et al. Quality of life in major depressive disorder before/after multiple steps of treatment and one-year follow-up. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2015;131(1):51–60. doi: 10.1111/acps.12301.

- Ivanova JI, Birnbaum HG, Kidolezi Y, et al. Direct and indirect costs of employees with treatment-resistant and non-treatment-resistant major depressive disorder. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26(10):2475–2484. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2010.517716.

- Gibson TB, Jing Y, Smith Carls G, et al. Cost burden of treatment resistance in patients with depression. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16(5):370–377.

- Gillain B, Degraeve G, Dreesen T, et al. Real-world treatment patterns, outcomes, resource utilization and costs in treatment-resistant major depressive disorder: PATTERN, a retrospective cohort study in Belgium. Pharmacoecon Open. 2022;6(2):293–302. doi: 10.1007/s41669-021-00306-2.

- Pérez-Sola V, Roca M, Alonso J, et al. Economic impact of treatment-resistant depression: a retrospective observational study. J Affect Disord. 2021;295:578–586. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.08.036.

- Ruggeri M, Drago C, Mandolini D, et al. The costs of treatment resistant depression: evidence from a survey among Italian patients. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2022;22(3):437–444. doi: 10.1080/14737167.2021.1954507.

- Conca A, Hinterhuber H, Prapotnik M, et al. Die Elektrokrampftherapie: Theorie und Praxis [Electroconvulsive therapy: theory and practice]. Neuropsychiatrie. 2004;18.1:1–17. German.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Health at a Glance 2021: OECD indicators. Paris (France): OECD Publishing; 2021.

- Turnpenny A, Petri G, Finn A, et al. Mapping and understanding exclusion: institutional, coercive and community-based services and practices across Europe. Brussels (Belgium): Mental Health Europe; 2017.