Abstract

Background

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) has embarked on a Health Sector Transformation Program as part of the Kingdom’s Vision 2030 initiatives with the facilitation of access to healthcare services for the millions in KSA with diabetes an essential part of the Program. Decision-making tools, such as budget impact models, are required to consider the addition of new medications like oral semaglutide that have multifaceted health benefits and address barriers related to therapeutic inertia to reduce diabetes-related complications.

Objective

To determine the financial impact of the introduction of oral semaglutide as a treatment option for people with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in KSA.

Methods

From the public payer’s perspective, the budget impact model estimates the costs before and after the introduction of oral semaglutide over a 5-year time horizon. The budget impact of introducing oral semaglutide (primary comparator) compared with three different classes of diabetes medicines: glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1), sodium-glucose transport protein 2 inhibitors (SGLT 2i) and dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors (DDP-4i) have been calculated based on the projected market shares. The model includes the cost of care through the incorporation of health outcomes that have an impact on the national payer’s budget in Saudi Riyals (SAR).

Results

The budget impact over the five-year time horizon indicates a medication cost increase (17,424,788 SAR), and cost offsets which include a difference in diabetes management costs (-3,625,287 SAR), CV complications costs (-810,733 SAR) and weight loss savings of 453,936 SAR. The cumulative total cost difference is 12,427,858 SAR (0.66%).

Conclusion

The introduction of oral semaglutide 14 mg as a second-line treatment option after metformin is indicated as budget-neutral to slightly budget-inflating for the public pharmaceutical formulary of KSA. The price difference is offset by positive health outcomes and costs. This conclusion was confirmed through a probabilistic sensitivity analysis.

Introduction

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) has embarked on a massive Health Sector Transformation ProgramCitation1 to restructure the health sector toward a comprehensive, effective, and integrated system based on individual and societal health. The foundation of the Program is value-based care which includes transparency and financial sustainability by promoting public health and preventing diseases, in addition to applying the new model of care related to disease prevention. The program was established in alignment with the Kingdom’s Vision 2030;Citation2 among the Program’s first objectives is to facilitate access to healthcare services, with diabetes, a chronic disease affecting millions of people in KSA, central to key health considerations.

KSA is among the top ten countries in the world with the highest prevalence of diabetes mellitus (DM) with a prevalence of ∼18.7% (4.3 million adults) in 2021 with millions more considered to have pre-diabetes.Citation3,Citation4 By 2030, KSA is expected to be among the top five countries with the highest prevalence of type 2 DM (T2DM).Citation3,Citation4

T2DM is associated with a high risk of complications including cardiovascular disease (CVD), nephropathy, neuropathy, retinopathy, and peripheral vascular disease. According to Al-Jedai, A. et al. (2022), there is a significant economic burden of T2DM patients with CVD and renal comorbidities.Citation5 This is an increasing healthcare resource utilization (HCRU) which includes hospitalizations and outpatient visits, particularly by patients with high CVD risk. For patients with established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) a glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist (GLP-1 RA) with proven benefit should be used to reduce major CVD events (MACE). A proven sodium-glucose transport protein 2 inhibitor (SGLT 2i) should be used for patients with heart failure (HF) to reduce MACE and improve kidney outcomes.Citation6

The Saudi National Diabetes Centre (SNDC) Guidelines recommend the glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) target in most adults with T2DM of <7% and consider metformin as the first-line pharmacological treatment,Citation7 with the understanding that T2DM is a progressive disease and additional interventions are necessary over time.Citation8 Healthcare practitioners and decision-makers are faced with multiple classes of medications at the second-line stage together with barriers to prescribing that produce therapeutic inertia which is a failure to intensify therapy to address poor glycemic control in a timely manner. Presently, only ∼25% of people with T2DM in KSA maintain good glycemic control,Citation9,Citation10 which puts a significant number of patients at risk for serious complications and potentially threatens the healthcare system with related exorbitant costs. The American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) 2022 consensus statements on the management of hyperglycemia in T2DM recommend a holistic, multifactorial, person-centric approach to T2DM management which continuously addresses CVD risk factor management, cardiorenal protection, glycemic, weight management and patient preference.Citation6

Physicians have expressed reluctance to prescribe subcutaneous medication for their patients due to patient non-adherence, patient refusal or elderly patients not having the ability to administer independently, leading to a failure to intensify therapy and ultimately diabetes-related complications.Citation10–12 Similarly, patients have expressed fear of injections (most common), preference for oral medications over injectables (76.5%), weight gain, hypoglycemia and social impacts related to second-line T2DM therapy.Citation6,Citation9,Citation10

Oral semaglutide, recently allowed as first-line therapy through a US Food and Drug Administration label update for adults with T2DM, is an intervention that is easier to prescribe and adhere to and may help address some of the physician and patient barriers that prevent improved glycemic control among patients in KSA with T2DM.Citation9,Citation13

New medications are being introduced that are considering additional health outcomes beyond the control of HbA1c, including CVD, and most recently, weight management. With the prevalence of obesity in KSA at 35.4% and overweight prevalence among the highest in the world at 69.7% in 2016, reducing weight is a crucial step for proper and sustained plasma glucose control.Citation7,Citation14,Citation15 Oral semaglutide for patients with T2DM offers glycemic control, weight control and CV, renal and additional benefits, in line with treatment guidelines that recommend a patient-centred approach including a review of individual risk for diabetes-related complications, BMI, and potential patient adherence issues.Citation16 Studies indicate that oral semaglutide, compared to other oral antidiabetic drugs empagliflozin and sitagliptin, provides superior HbA1c reductions in patients with T2DM (up to 1.8%) and provides superior weight reduction (up to 6.4 kg).Citation6 Further, almost 80% of patients reported good or very good treatment satisfaction with oral semaglutide.Citation6

The introduction of new healthcare interventions requires careful decision-making on the part of the budget holder. Analysis over time with the incorporation of multiple aspects of the health system and patient health outcomes is becoming an increasingly important tool. The Health Sector Transformation Program in KSA incorporates a focus on health technology assessment (HTA),Citation17 with a recently established HTA entity to contribute to the decision-making process. This focus aligns with an interest in health economic evaluation wherein reforms and infrastructure improvements required to build capacity are underway.Citation18 As of 2022, economic analysis of health technologies is limited in KSA and challenged by lack of data and especially country-specific data.Citation18 The development of a budget impact analysis for the introduction of oral semaglutide seeks to offer findings from this important tool to decision-makers in KSA to augment HTA program information and contribute to the growing area of health economic analysis in KSA with the objective to determine the financial impact of the introduction of oral semaglutide as a treatment option for people with T2DM from a Saudi public payer perspective.

Methods

Population

The population included in the budget impact analysis includes patients with T2DM who have failed to achieve their HbA1c targets with metformin. Based on the SNDC Guidelines, these patients should receive second-line treatment which may include combination therapy of metformin plus a GLP-1 RA including semaglutide subcutaneous (SC), dulaglutide or liraglutide; oral semaglutide; a sodium-glucose transport protein 2 inhibitor (SGLT 2i) including empagliflozin, dapagliflozin; or a dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitor (DPP-4i) including sitagliptin, vildagliptin, or linagliptin.Citation7 A patient-centric approach to treatment selection is recommended with a review of comorbidities including obesity. For patients with established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) or chronic kidney disease (CKD), a GLP-1 RA or SGLT 2i is recommended as second-line therapy; for patients with a greater need for glucose-lowering effect from their medication a GLP-1 RA is recommended, and for patients with HF, a SGLT 2i is preferred. Further, the ADA/EASD consensus statements indicate that semaglutide is recommended as a first-line GLP-1 RA with proven CVD benefit with a significant impact on reducing the risk of MACE, including non-fatal stroke, in high-risk patients with T2DM.Citation6 For people with T2DM who are uncontrolled on metformin and living with obesity, the SNDC Guidelines recommended a GLP-1 RA or SGLT-2i for their good effect on weight loss.Citation7 Semaglutide therapy for patients with T2DM offers high efficacy in both body weight reduction and glucose control.

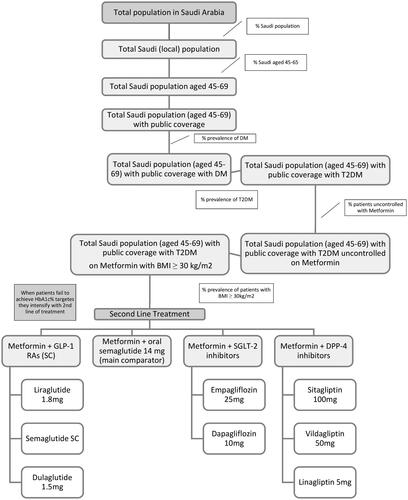

The patient flow diagram () illustrates the T2DM population and the comparators of the budget impact analysis (second-line therapy).

The affected patient population was derived from the starting total population size of Saudi Arabia through the application of epidemiological data on the Saudi population, public and private coverage, prevalence of DM (18%), the prevalence of T2DM (95%), the incidence of T2DM (1.0%), age (45–69 years), patients uncontrolled on metformin (40%) and BMI ranges greater than 30 kg/m2.Citation19–21 ( and ) The target population age was based on the baseline characteristics in the Pioneer Program wherein Pioneer (2)Citation27 the population age was 57 years (standard deviation (SD) =10 years), and in Pioneer (3)Citation28 the population age was 58 years (SD = 10 years). Data availability regarding the relative risk reduction associated with the mean weight loss derived from available local literature limited the upper limit of the age range.Citation29 The specialty senior population was not intended to be included in this study.

Table 1. Basic model Parameters: Population Breakdown.

Comparators

The budget impact analysis was conducted from the perspective of the KSA public health payer. The classes of medications included GLP-1 RAs, SGLT 2i and DPP-4i. The model included the direct medical costs of care through the incorporation of different health outcomes that have an impact on the national payer’s budget: proportion of patients achieving HbA1c% target (<7); cardiovascular risk reduction as a cost offset; budget savings as a result from weight loss (impact of GLP-1 RAs). These direct medical costs correlate to the patient profiles for appropriate allocation of treatment from the Saudi Diabetes Clinical Practice Guidelines including HbA1c target achievement, BMI, comorbidities including HF, ASCVD, and CKD.Citation7 Indirect costs were not included as they are not relevant to the payer’s perspective. Unit costs were derived from local economic evidence and inflated to the current prices using the Saudi Consumer Price Indices (CPI) and the public tender price was used for the medication costs. The model was designed to incorporate chosen health outcomes to produce the budget impact results.

The primary comparator was the newly introduced oral semaglutide 14 mg against three classes of diabetes medicines. These include three groups of comparators: injectable GLP-1 RAs (semaglutide SC, dulaglutide 1.5 mg, liraglutide 1.8 mg); SGLT 2i (empagliflozin, dapagliflozin); and DPP-4i (sitagliptin, vildagliptin, linagliptin) (). The inclusion of each comparator and comparator grouping is separately modifiable in the model. Groupings were determined by class of medication with the values determined through a weighted average based on the market share derived from the IQVIA report.Citation30

Table 2. Budget impact model comparators.

KSA Ministry of Health decision-makers identified the relevant comparators at the scoping stage of the study based on clinical practice in the KSA public sector and local diabetes guidelines in the development of the model. Though insulin is considered one of the strongest glucose-lowering agents, according to the consensus report by the ADA and EASD,Citation6 insulin is the preferred option for patients whose HbA1c is more than 10% and associated with symptoms like weight loss or ketonuria/ketosis and with acute glycemic dysregulation, which is not the case for the model target population. Increasing evidence supports the utilization of other regimens e.g. GLP-1 RA, SGLT-2i in particular patient profiles (CV and renal complications and overweight) which is in alignment with the SNDC Guidelines.Citation7

Inputs

Basic model Parameters

The basic model parameters involved standard inputs such as population size, time horizon, prevalence and incidence information, age and BMI ranges ().

Table 3. Basic model parameters.

The five-year time horizon was the requested period by public payers in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, with a year-to-year budget impact also included in the results.

Market mix

The market mix scenarios were considered with (new scenario) and without (current scenario) the inclusion of oral semaglutide 14 mg over a five-year time horizon. The market mix includes GLP-1 RAs (primary competitor), SGLT 2i and DPP-4i (secondary comparator to accommodate for the attrition impact) with market percentages determined through IQVIA market intelligence reportsCitation30 ().

Table 4. Market mix*.

Model input Parameters

The clinical outcomes incorporated into the model () reflect available data on comorbidities associated with T2DM. These included cardiovascular (CV) risk reduction related to T2DM treatments, specifically the 3-point major CV event outcome (3 P-MACE), CV death, non-fatal stroke and non-fatal myocardial infarction (MI); the proportion of patients with uncontrolled HbA1c (>7.0%), together with HbA1c reduction; weight reduction as a health outcome (derived from Value of Weight Loss Tool (VOWL), Saudi Version);Citation29 and weight loss saving impact on health outcomes and risk reduction related to CKD, HF, hypertension and dyslipidemia.

Table 5. Model inputs—CV risk reduction*.

Table 6. Model inputs—proportion of patients uncontrolled HbA1c.

Table 7. Model inputs—weight reduction.

Table 8. Model inputs: weight-loss saving impact.

Diabetes management costs (including laboratory tests, hospitalization, outpatient visits, specialists, dietary education, and others) were incorporated for patients with T2DM with HbA1c less than 7%, between 7% and 9% and greater than 9% (). Further, costs related to T2DM comorbidities were considered based on costs per patient and converted into SAR and inflated to current values using the Saudi consumer price indices ().

The model input for proportion of patients with uncontrolled HbA1c will be transformed to annual values using standardized transformation techniques.

Sensitivity analyses

Probabilistic and deterministic sensitivity analyses were conducted by attributing the option of Beta, Lognormal, or Gamma distributions to each input parameter in the series as detailed in . The probabilistic sensitivity analysis assessed the robustness of the BIM and determined the probability of budget inflation greater than 5, 10 and 15% and the probability of budget savings greater than 5, 10 and 15%. Deterministic sensitivity analyses were conducted to investigate the sensitivity of the outcomes based on the impact of the input parameters on the results of the model.

Model outcomes

The results from the BIM are intended to determine the budget impact year over year and of introducing oral semaglutide to the KSA public pharmaceutical formulary together with the impact on the overall budget with a five-year time horizon. Results will additionally reveal the impact on health outcomes including the number of CV events, the number of patients with T2DM achieving HbA1c target, and weight loss savings per scenario.

Results

Healthcare budget impact

The healthcare budget impact realized with the introduction of oral semaglutide 14 mg was reported year by year and over five years and included medication costs, diabetes management costs, CV complication costs, weight loss savings and total cost impact. In year 2024, the addition of oral semaglutide increased medication costs by 1,973,048 SAR, decreased diabetes management costs (-460,924 SAR) and CV complications costs (-65,766 SAR) and provided weight loss savings (75,401 SAR). In year 2025, the addition of oral semaglutide increased medication costs by 3,540,287 SAR, decreased diabetes management costs (-748,411 SAR) and CV complication costs (-144,761 SAR) and realized weight loss savings (92,451 SAR). In year 2026, medication costs increased by 5,114,810 SAR, diabetes management costs (-1,010,780 SAR) and CV complication costs (-230,078 SAR) decreased, and cost savings were realized for weight loss (109,849 SAR). By year 2027, the introduction of oral semaglutide will increase medication costs by 6,692,173 SAR, CV complications costs decrease (-403,734 SAR), and diabetes management costs decrease (-1,414,715 SAR), and weight loss cost savings were realized (174,760 SAR) ().

The budget impact over the complete time horizon (cumulative five years) indicates a medication cost increase (17,424,788 SAR), and cost offsets which includes a difference in diabetes management costs (-3,625,287 SAR), CV complications costs (-810,733 SAR) and weight loss savings of 453,936 SAR. The total cost differential is 0.66% (12,427,858 SAR) (). Detailed comparative costs of each medication is included in the appendix ().

Table 9. Budget impact over full time horizon.

Health outcomes impact

The impact on health outcomes, as they relate to people with T2DM when oral semaglutide is introduced is evident. The number of patients achieving HbA1c target (<7%) increased by ∼1,500 patients; the number of CV deaths is reduced by 95 patients; the number of non-fatal strokes is reduced by four events; the number of non-fatal MI events is increased by 67; and the number of severe hypoglycemia episodes is reduced by 71.

Sensitivity analysis

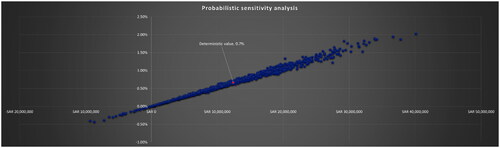

The probabilistic sensitivity analysis considered 115 variables by attributing different distributions to the input parameters. These included multi-faceted prevalence data, prices, health outcomes by therapy, and costs associated with comorbid events. The analysis supported the results of the BIM, with the probability of inflating the healthcare budget by more than 2% being less than 0.01 ().

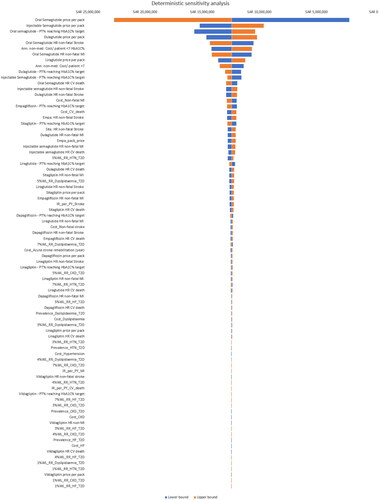

The deterministic sensitivity analysis considered 82 variables revealing top input parameters including oral and injectable semaglutide, dulaglutide price per pack and oral semaglutide proportion of patients achieving HbA1C% target were the top input parameters that impacted the results of the model ().

Discussion

The objective of this analysis was to determine the budget impact of introducing oral semaglutide as a treatment option for patients with T2DM in KSA. The results reported with high confidence indicated an increase in medication costs offset by a reduction in DM management costs, CV complications costs and savings realized through patient weight loss. The findings indicated that the introduction of oral semaglutide is budget neutral to cost saving, allowing for a focus on other considerations related to the treatment of patients with T2DM in KSA. These may include factors influencing therapeutic inertia, medication adherence and the modern realities of the KSA population that include high T2DM and obesity rates reflected in the strategic objectives of the KSA Health Sector Transformation Program.Citation1

Understanding the cost implications of this new therapeutic option for people with T2DM is a vital contribution to decision-making and healthcare budget planning in KSA. Results derived from randomized controlled trials further confirmed positive health outcomes for patients with T2DM in terms of improved HbA1c results, fewer hypoglycemic events, and weight loss benefits.Citation6 These findings together allow for consideration of this new intervention and how it will address challenges among the growing T2DM population in KSA, assured that it will not overwhelm the resources of the healthcare budget.

Insight into the barriers to second-line therapy for patients with T2DM provides an important patient/prescriber perspective. Consideration of KSA-specific healthcare costs offers a clear understanding of the budget impact, and analysis of KSA-specific health outcomes provides a comprehensive understanding of the healthcare environment. The results of the budget impact analysis of the main comparator, oral semaglutide, to be considered against the available treatment modalities in KSA from the public payer’s perspective, offer insights that the introduction of oral semaglutide as a second-line intervention will have a positive impact on health outcomes and not affect the healthcare budget negatively.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of the budget impact analysis include the consideration of costs at a population level so that the impact on the public healthcare budget as a whole may be determined. The comprehensive sensitivity analysis offers confidence in the probabilities presented in the findings. The analytical approach selected through the unique BIM is an appropriate means to determine the budget impact of the introduction of oral semaglutide 14 mg in KSA. These important connections in the development of this work allowed for key opinion leaders to populate the model pertaining to model input costs due to the scarcity of this information and the complexity of the care required (e.g. testing, specialist support, emergency room, nursing, hospital stay, etc.).

Overarching limitations of the budget impact analysis were the lack of KSA-specific data, an underlying challenge of all economic analyses of health technologies.Citation18

Specifically related to cardiovascular risk-reduction, the BIA was limited by the lack of meta-analysis that included all comparators. For GLP-1 (the main comparators) indirect treatment comparison was used and cardiovascular outcome trials comparing the medication versus placebo were used for DPP-4i and SGLT-2i; though quite similar in methodology, this is considered a limitation due to the heterogeneous population.

Conclusion

The introduction of oral semaglutide 14 mg as a second-line treatment after metformin is budget-neutral to slightly budget-inflating for the public pharmaceutical formulary of KSA. The price difference is offset by positive health outcomes including more patients in KSA achieving HbA1c targets, fewer CV events and impactful weight-loss cost savings. This conclusion was confirmed through a probabilistic sensitivity analysis.

Transparency

Author contributions

All authors were involved in the development of the model, analysis and contributed to the final manuscript.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Janet Crain (KTE Bridge Consulting, Canada) for medical writing assistance in the preparation of this manuscript, funded by NovoNordisk, KSA.

Declaration of funding

This work was funded by NovoNordisk, KSA.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

MA has received speaker’s honoraria from NovoNordisk, KSA.

The other authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

- Health Sector Transformation Program; Delivery Plan. 2021. Ministry of Health, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. https://www.vision2030.gov.sa/media/p2lfgxe4/delivery-plan-en-hstp.pdf. Accessed 18 June 2023.

- Vision 2030—Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Council of Economic and Development Affairs, Government of Saudi Arabia. https://www.vision2030.gov.sa/media/rc0b5oy1/saudi_vision203.pdf. Accessed 18 June 2023.

- International Diabetes Federation. IDF diabetes atlas. International Diabetes Federation, Brussels, Belgium, 8th edition, 2017. http://www.diabetesatlas.org. Accessed 16 June 2023.

- Al Dawish MA, Robert AA, Braham R, et al. Diabetes mellitus in Saudi Arabia: a review of the recent literature. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2016;12(4):359–368. doi: 10.2174/1573399811666150724095130.

- Al-Jedai AH, Almudaiheem HY, Alissa DA, et al. Cost of cardiovascular diseases and renal complications in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia: a retrospective analysis of claims database. PLoS One. 2022;17(10):e0273836. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0273836.

- Davies MJ, Aroda VR, Collins BS, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2022. A consensus report by the American diabetes association (ADA) and the European association for the study of diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care. 2022;45(11):2753–2786. doi: 10.2337/dci22-0034.

- Saudi Diabetes Clinical Practice Guidelines (SDCPG), Saudi National Diabetes Center (SNDC), Saudi Health Council. 2021. https://shc.gov.sa/Arabic/Documents/SDCP%20Guidelines.pdf. Accessed 18 June 2023.

- Fonseca VA. Defining and characterizing the progression of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009; 32(Suppl 2):S151–S6. doi: 10.2337/dc09-S301.

- Alromaih A, Alshamrani A, Alharbi B, et al. Saudi consensus for oral semaglutide, the recent innovation in GLP-1 RAs era; consensus report. JDM. 2023;13(02):222–238. doi: 10.4236/jdm.2023.132017.

- Alhagawy AJ, Yafei S, Hummadi A, et al. Barriers and attitudes of primary healthcare physicians to insulin initiation and intensification in Saudi Arabia. IJERPH. 2022;19(24):16794. doi: 10.3390/ijerph192416794.

- Bain SC, Bekker Hansen B, Hunt B, et al. Evaluating the burden of poor glycemic control associated with therapeutic inertia in patients with type 2 diabetes in the UK. J Med Econ. 2020;23(1):98–105. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2019.1645018.

- Khayyat SM, Mohamed MMA, Khayyat SMS, et al. Association between medication adherence and quality of life of patients with diabetes and hypertension attending primary care clinics; a cross-sectional survey. Qual Life Res. 2019;28(4):1053–1061. doi: 10.1007/s11136-018-2060-8.

- Josh SR, Rajput R, Chowdhury S, et al. The role of oral semaglutide in managing type 2 diabetes in Indian clinical settings: addressing the unmet needs. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2022;16(6):102508. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2022.1025081871-4021.

- World Health Organization. 2016. Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/. Accessed 16 June 2023.

- Wondmkun YT. Obesity, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes: associations and therapeutic implications. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2020; 13:3611–3616. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S275898.

- Hansen BB, Nuhoho S, Ali SN, et al. Oral semaglutide versus injectable glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists: a cost of control analysis. J Med Econ. 2020;23(6):650–658. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2020.1722678.

- Fasseeh A, Karam R, Jameleddine M, et al. Implementation of health technology assessment in the Middle east and North africa: comparison between the current and preferred status. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:15. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.00015.

- Maraiki F, Bazarbashi S, Scuffham P, et al. Methodological approaches to cost-effectiveness analysis in Saudi Arabia: what can we learn? A systematic review. MDM Policy Pract. 2022;7(1):23814683221086869. doi: 10.1177/23814683221086869.

- Diabetes Atlas. 2021, IDF diabetes Atlas, Saudi Arabia, https://diabetesatlas.org/data/en/country/174/sa.html. Accessed 15 Aug 2022.

- Brown JB, Conner C, Nichols GA. ‘Secondary failure of metformin monotherapy in clinical practice’. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/40812417_Secondary_Failure_of_Metformin_Monotherapy_in_Clinical_Practice.

- Tucker M. 2023, ‘Metformin Monotherapy Not Always Best Start in Type 2 Diabetes’. Available at: https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/986994?&icd=login_success_email_match_fpf.

- Saudi Census. 2022. General Authority for Statistics of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia; https://portal.saudicensus.sa/portal/public/1/18/101511?type=TABLE.

- GASTAT Database. General Authority for Statistics of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia; https://database.stats.gov.sa/home/indicator/535.

- Open Data Library. Council of Health Insurance; Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. https://chi.gov.sa/OpenData/Pages/Documents/2021.pdf.

- World Health Survey Saudi Arabia. 2019. Ministry of Health, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Ministry/Statistics/Population-Health-Indicators/Documents/World-Health-Survey-Saudi-Arabia.pdf.

- Malkin JD, Baid D, Alsukait RF, et al. The economic burden of overweight and obesity in Saudi Arabia. Plos One. 2022;17(3):e0264993. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0264993.

- Rodbard HW, Rosenstock J, Canani LH, et al. Oral semaglutide versus empagliflozin in patients with type 2 diabetes uncontrolled on metformin: the PIONEER 2 trial. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(12):2272–2281. doi: 10.2337/dc19-0883.

- Rosenstock J, Allison D, Birkenfeld AL, et al. Effect of additional oral semaglutide vs sitagliptin on glycated hemoglobin in adults with type 2 diabetes uncontrolled with metformin alone or with sulfonylurea: the PIONEER 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;321(15):1466–1480. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.2942.

- Alqahtani SA, Al-Omar HA, Alshehri A, et al. Obesity burden and impact of weight loss in Saudi Arabia: a modelling study. Adv Ther. 2023;40(3):1114–1128. doi: 10.1007/s12325-022-02415-8.

- Medicine Market Intelligence Reports. IQVIA Institute for Human Data Science. 2022. Accessed 15 Aug 2022.

- Raghavan S, Vassy JL, Ho Y-L, et al. Diabetes mellitus-related all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in a national cohort of adults. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8(4):e011295. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.011295.

- Kothari V, Stevens RJ, Adler AI, et al. UKPDS 60: risk of stroke in type 2 diabetes estimated by the UK prospective diabetes study risk engine. Stroke. 2002;33(7):1776–1781. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000020091.07144.c7.

- Mulnier HE, Seaman HE, Raleigh VS, et al. Risk of myocardial infarction in men and women with type 2 diabetes in the UK: a cohort study using the general practice research database. Diabetologia. 2008;51(9):1639–1645. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-1076-y.

- Husain M, Birkenfeld AL, Donsmark M, et al. Oral semaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(9):841–851. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1901118.

- Leiter LA, Bain SC, Hramiak I, et al. Cardiovascular risk reduction with once-weekly semaglutide in subjects with type 2 diabetes: a post hoc analysis of gender, age, and baseline CV risk profile in the SUSTAIN 6 trial. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2019;18(1):73. doi: 10.1186/s12933-019-0871-8.

- Gerstein HC, Colhoun HM, Dagenais GR, et al. Dulaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes (REWIND): a double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2019;394(10193):121–130. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31149-3.

- Marso SP, Daniels GH, Brown-Frandsen K, et al. Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(4):311–322. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603827.

- Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM, et al. Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes and mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(22):2117–2128. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504720.

- Wiviott SD, Raz I, Bonaca MP, et al. Dapagliflozin and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(4):347–357. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1812389.

- Green JB, Bethel MA, Armstrong PW, et al. Effect of sitagliptin on cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(3):232–242. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1501352.

- Chen D-Y, Li Y-R, Mao C-T, et al. Cardiovascular outcomes of vildagliptin in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus after acute coronary syndrome or acute ischemic stroke. J Diabetes Investig. 2020;11(1):110–124. doi: 10.1111/jdi.13078.

- Li Y-R, Tsai S-S, Chen D-Y, et al. Linagliptin and cardiovascular outcome in type 2 diabetes after acute coronary syndrome or acute ischemic stroke. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2018;17(1):2. doi: 10.1186/s12933-017-0655-y.

- Bailey C, Gross J, Pieters A, et al. Effect of dapagliflozin in patients with type 2 diabetes who have inadequate glyaemic control with metformin: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;375:223–2233.

- Bosi E, Camisasca RP, Collober C, et al. Effects of vildagliptin on glucose control over 24 weeks in patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled with metformin. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(4):890–895. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1732.

- Taskinen M-R, Rosenstock J, Tamminen I, et al. Safety and efficacy of linagliptin as add-on therapy to metformin in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2011;13(1):65–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2010.01326.x.

- Pratley RE, Aroda VR, Lingvay I, et al. Semaglutide versus dulaglutide once weekly in patients with type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN 7): a randomised, open-label, phase 3b trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;6(4):275–286. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(18)30024-X.

- Alzaid A, Ladrón de Guevara P, Beillat M, et al. Burden of disease and costs associated with type 2 diabetes in emerging and established markets: systematic review analyses. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2021;21(4):785–798. doi: 10.1080/14737167.2020.1782748.

- Khalid SA, Samia AB, Bandari KA. Hypertension in Saudi adults with type 2 diabetes. Interventions Obes Diab. 2018; 1(4). doi: 10.31031/IOD.2018.01.000518.

- Alzaheb R, Altemani A. Prevalence and associated factors of dyslipidemia among adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Saudi Arabia. DMSO. 2020;13:4033–4040. https://dovepress.com/getfile.php?fileID=62983 doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S246068.

- Almutairi N, Alkharfy KM. Direct medical cost and glycemic control in type 2 diabetic saudi patients. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2013;11(6):671–675. doi: 10.1007/s40258-013-0065-6.

- Almalki Z, Alatawi Y, Alharbi A, et al. Cost-effectiveness of more intensive blood pressure treatment in patients with high risk of cardiovascular disease in Saudi Arabia. Int J Hypertens. 2019;2019:6019401. doi: 10.1155/2019/6019401.

- Hnoosh A, Vega-Hernández G, Jugrin A, et al. PDB45 direct medical costs of diabetes-related complications in Saudi Arabia. Value in Health. 2012;15(4):A178. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2012.03.966.

- Expert Opinion.

- Osman AM, Alsultan MS, Al-Mutairi MA. The burden of ischemic heart disease at a major cardiac center in Central Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2011; 32(12):1279–1284.

Appendices

Table A1. Basic model parameters: population breakdown—detailed calculation.

Table A2. Model inputs—annual non-medication costs per patient.

Table A3. Model inputs—prevalence of comorbidities in T2DM population.

Table A4. Probabilistic sensitivity analyses distribution.

Table A5. Year over year healthcare budget impact.

Table A6. Current scenario (without oral semaglutide 14 mg).

Table A7. New scenario (with oral semaglutide 14 mg).