Abstract

Background

Rett syndrome (RTT) is a severe neurodevelopmental disorder. Management strategies are heterogeneous with no clear definition of success. This study describes physician decision-making regarding diagnosis, therapeutic goals, and management strategies to better understand RTT clinical management in the US.

Methods

This study was conducted among practicing physicians, specifically neurologists and pediatricians in the US with experience treating ≥2 individuals with RTT, including ≥1 individuals within the past two years. In-depth interviews with five physicians informed survey development. A cross-sectional survey was then conducted among 100 physicians.

Results

Neurologists had treated more individuals with RTT (median: 12 vs. 5, p < 0.001) than pediatricians throughout their career and were more likely to report being “very comfortable” managing RTT (31 vs. 4%, p < 0.001). Among physicians with experience diagnosing RTT (93%), most evaluated symptoms (91%) or used genetic testing (86%) for RTT diagnoses; neurologists used the 2010 consensus diagnostic criteria more than pediatricians (54 vs. 29%; p = 0.012). Improving the quality of life (QOL) of individuals with RTT was the most important therapeutic goal among physicians, followed by improving caregivers’ QOL. Most physicians used clinical practice guidelines to monitor the progress of individuals with RTT, although neurologists relied more on clinical scales than pediatricians. Among all physicians, the most commonly treated symptoms included behavioral issues, epilepsy/seizures, and feeding issues. Management strategies varied by symptom, with referral to appropriate specialists being common across symptoms. A large proportion of physicians (37%) identified the lack of novel therapies and reliance on symptom-specific management as an unmet need.

Conclusion

Although most physicians had experience and were comfortable diagnosing and treating individuals with RTT, better education and support among pediatricians is warranted. Additionally, novel treatments that target multiple symptoms associated with RTT could reduce the burden and improve the QOL of individuals with RTT and their caregivers.

Introduction

Rett syndrome (RTT) is a debilitating neurodevelopmental disorder, with an incidence of 1 out of every 10,000 to 15,000 live female births worldwideCitation1. It is one of the most common genetic causes of developmental and intellectual disability in girlsCitation2,Citation3. In terms of etiology, most individuals affected by RTT have one of >300 distinct loss-of-function mutations in the methyl-CpG binding protein-2 (MECP2) gene on the X chromosome, which encodes the MeCP2 proteinCitation4,Citation5. Individuals with RTT may exhibit seemingly normal early development with a period of regression that becomes most apparent around 12─24 months of age and then stabilizes thereafterCitation6–9. However, growing evidence suggests that more subtle clinical signs of RTT may occur before then, with some studies reporting them as early as 12 months of ageCitation10–13. Indeed, the 2006 guidelines of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) has recommended developmental surveillance and screening beginning as early as 9 months of ageCitation14. Nonetheless, the diagnosis of RTT remains a clinical one based primarily on the key features that are most apparent during regression, including the loss of purposeful hand use and spoken language, with the development of gait abnormalities and hand stereotypiesCitation9. In addition, genetic testing for MECP2 may also be conductedCitation3,Citation7, although it is not a necessary diagnostic criterionCitation9.

The diagnosis of individuals with RTT continues to pose a considerable challenge in clinical practice. Although the identification of RTT should ideally be based on early signs of abnormal development (i.e. before 5 years of age)Citation9,Citation10,Citation14,Citation15, delayed diagnoses are common among individuals with RTTCitation14,Citation16. This may be partly attributable to the clinical heterogeneity of the disease, as many individuals might present with a subset of the key clinical features, or other features that are atypical of those most commonly present among individuals with RTT, resulting in a diagnosis of “atypical” or “variant” RTTCitation9,Citation15. Based on growing knowledge of the clinical manifestations and associated variations in RTT, and to simplify diagnosis and improve clinical management, the 2002 diagnostic criteria were updated in 2010 using the consensus of experts who had treated a large sample of individuals with RTTCitation9,Citation17. The previous criteria of 2002 consisted of eight necessary criteria, five exclusion criteria, and eight supportive criteriaCitation17,Citation18. However, there were no clearly stated requirements for meeting these criteria and one of the necessary criteria (postnatal deceleration of head growth in majority) was not absolutely required, which might have contributed to diagnostic confusionCitation9,Citation17,Citation18. According to the revised 2010 diagnostic criteria, necessary requirements for a diagnosis of typical or “classic” RTT include a period of regression followed by recovery or stabilization, four main criteria, and two exclusion criteria. In addition, there are 11 supportive criteria not required for a diagnosis that often present in typical RTTCitation9. For all the updated 2010 diagnostic criteria, the requirements were explicitly statedCitation9. In addition to revising the diagnostic criteria for typical RTT, the 2010 diagnostic criteria clarified the clinical criteria for atypical RTT and developed new guidelines for the diagnosis and molecular evaluation of specific variant forms of atypical RTTCitation9. Despite the availability of these revised criteria, the early detection of individuals with abnormal development remains a challengeCitation10,Citation14,Citation15,Citation19,Citation20. For instance, a 2005 survey by the AAP reported that few pediatricians use effective, standardized means to screen individuals for developmental problemsCitation16. Although pediatricians’ reported use of developmental screening tools increased from 21% in 2002 to 63% in 2016, additional efforts are needed to boost these numbers and improve referral systemsCitation20. Thus, a greater focus on the challenges faced by pediatric healthcare professionals in identifying individuals with developmental disorders, including RTT, is warrantedCitation7,Citation14,Citation16,Citation19.

Since the symptoms and multisystem comorbidities in RTT vary from one person to the next, and evolve throughout the lifespan, RTT management strategies tend to be highly heterogeneous and individually tailoredCitation7,Citation21,Citation22. As a result, individuals with RTT often require lifelong care due to the wide range of varying clinical manifestations over the lifespan, including neurological, gastrointestinal, cardiac, endocrine, and orthopedic disordersCitation21. Historically, most available pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapy options for RTT have been aimed at managing symptoms and facilitating daily livingCitation3,Citation23–27. To promote childhood development, consensus guidelines recommend early referral to physical, occupational, and speech language therapists, as well as the establishment of an individualized education programCitation7. For individuals whose disorder has progressed enough to significantly impede their daily functioning, potentially expensive devices such as wheelchairs, electronic activity monitors, or speech-generating aids may be necessaryCitation28,Citation29. In an effort to assist physicians and caregivers in addressing these myriad symptoms, a 2020 consensus of experts has developed guidelines on monitoring and managing RTT throughout the lifespanCitation7.

In March 2023, trofinetide, an orally bioavailable synthetic analog of glycine-proline-glutamate, the N-terminal tripeptide of the insulin-like growth factor 1 proteinCitation30, has become the first prescription therapy approved by the US Food and Drug Administration specifically for the treatment of individuals with RTTCitation31. This approval was based on the results of a 12-week, phase 3 randomized clinical trial, in which trofinetide was associated with significant improvements in RTT overall, as well as improvements in specific symptoms such as mood disruption, maladaptive behaviors, and motor skillsCitation30. Thus, the recent approval of trofinetide may transform the management of individuals with RTT in the coming years. However, due to the wide variations in RTT clinical manifestations, there is still a lack of clarity on how to define success in treating individuals with RTT, which causes challenges in developing appropriate treatments. Furthermore, limited awareness about RTT among pediatricians and primary care providers is acknowledged as a rate-limiting step in the timely identification, management, and treatment of individuals with RTTCitation15,Citation16,Citation32,Citation33.

These barriers to diagnosis and treatment among individuals with RTT can result in a considerable burden, both on the healthcare system as well as on individuals with RTT and their caregivers, with frequent specialist referrals and use of expensive medical devices potentially throughout a patient’s lifeCitation22. A contemporary description of RTT management practices might help to mitigate this burden by underscoring therapeutic gaps and unmet needs, which could in turn inform the development of novel pharmacological treatments. However, there is currently limited evidence regarding physicians’ experience and approaches to diagnosing and managing RTT in routine clinical practice. Thus, to better understand the real-world management strategies and therapeutic goals in RTT clinical practice, we conducted in-depth interviews and a cross-sectional survey among physicians managing individuals with RTT in the US.

Methods

Study design

This study used a two-phase, mixed methods research approach previously described in the literatureCitation34–36. During the qualitative phase, in-depth interviews were conducted among neurologists and pediatricians practicing in the US, who were experienced in the management of individuals with RTT (i.e. RTT-treating physicians). Key themes were extracted from these interviews and used to inform the development of a survey in the quantitative phase, designed to enable RTT-treating physicians to report on the diagnostic methods, therapeutic goals, and therapeutic strategies used to manage individuals with RTT in their care. The quantitative survey was launched among a larger pool of RTT-treating physicians representing the broader population of physicians in the US. During both the qualitative and quantitative phases, physicians reported on the study measures and outcomes based on their professional experience during the entire time spent managing individuals with RTT (i.e. since becoming licensed physicians). Ethics approval for this study was obtained from the Pearl Institutional Review Board (IRB approval number: 21-ANGR-104).

Study participants

Eligible physicians participating in the qualitative interviews and quantitative survey were required to meet the following four criteria: (1) neurologist or pediatrician practicing in the US, (2) experienced in treating at least two individuals with RTT at any time, (3) treated at least one individual with RTT in the past two years, and (4) willing to provide informed consent to participate in the study. Physicians who had seen an unexpected number and proportion of male individuals with RTT in their care were excluded (based on input from clinical experts). Thus, over their entire time spent managing individuals with RTT, all included physicians had either seen ≤2 male individuals with RTT or ≤20% of individuals with RTT in their care had been male.

Materials and procedures

Qualitative phase

Semi-structured, in-depth interviews lasting approximately 60–90 min were conducted with five eligible physicians. All interviews were carried out from 9 July through 30 July 2021, by researchers or other trained personnel using an online conferencing platform. Important themes and key insights regarding the diagnostic and therapeutic strategies used by physicians to manage individuals with RTT under their care were extracted from the audio-recorded and transcribed interviews.

Quantitative phase

Key themes identified from the in-depth interviews were used to inform the development of a cross-sectional survey for RTT-treating physicians. The survey instrument included a short screening section to ensure the eligibility of all respondents followed by a 20-minute questionnaire. While all response options were informed by the interview results, the multiple-choice format of the questions allowed the survey responses to be easily quantified and summarized. Following a pilot test among three physicians and subsequent modifications to the survey instrument based on the results of the pilot, the survey was fully launched among RTT-treating physicians identified through a physician panel (Medefield). Included physicians were from a wide range of practice settings and geographic locations in the US. During the full launch, 100 eligible participating physicians completed the web-based survey, made accessible via an internet link from 23 November to 20 January 2022.

Study measures and outcomes

In the quantitative survey, physicians provided details regarding their experience managing individuals with RTT, therapeutic goals, and real-world management strategies. Experience managing individuals with RTT included the number of individuals with RTT treated throughout the physicians’ career, comfort level managing individuals with RTT, their most recent encounter, and the longest duration having provided care. Among those who had ever newly assigned or confirmed RTT diagnoses, physicians reported their most recent RTT diagnosis, the diagnostic criteria/tests used to assign/confirm RTT diagnosis, whether they typically assigned a RTT classification (classic or variant/atypical RTT) during diagnosis, whether they typically considered alternative diagnoses when an individual presents with RTT-like symptoms, and if so, which alternative diagnoses they considered. With respect to therapeutic goals, physicians were asked to rank potential therapeutic goals from two different perspectives: (1) their own perspective and (2) what they would consider to be the perspective of individuals with RTT and their caregivers based on their experiences with this population in the clinical setting. The five potential therapeutic goals were ranked from 1 to 5, with 5 being the most important goal and 1 being the fifth most important goal. Physicians also reported on real-world management practices including clinical scales, tests, or guidelines typically used to monitor progress, factors considered when recommending therapy for symptom control, and the most common management strategies employed for each commonly seen symptom.

Statistical analysis

For the qualitative phase, a descriptive summary of the main findings of the transcribed interviews was prepared, which included key insights regarding each of the study objectives, along with a listing of variables and response options for inclusion during the quantitative phase. During the quantitative phase, survey data were cleaned and processed for use in the analysis through the creation, labeling, and formatting of analytic variables, the coding of missing values, and the flagging of outliers and other data inconsistencies.

Information on physicians’ experience managing individuals with RTT, therapeutic goals, and real-world management strategies were assessed using descriptive statistics, including numbers and proportions (%), means and standard deviations (SD), or medians and interquartile ranges (IQR). Additionally, the importance of RTT therapeutic goals was assessed using a mean rank. Each physician ranked up to five goals from 1 to 5, with 5 being the most important goal and 1 being the fifth most important goal, while therapeutic goals not ranked were given a score of 0. Results were described overall and stratified by specialty of RTT-treating physicians, namely pediatricians (including developmental pediatricians) and neurologists (including pediatric neurologists, neurologists who were also geneticists, and neurologists who were also RTT specialists).

Results

Physician characteristics

The qualitative phase included two key opinion leaders (KOLs) specializing in pediatric neurology with expertise in RTT, one general neurologist, and two pediatricians (one of whom specialized in developmental medicine). The physicians practiced in California, Connecticut, Indiana, and Tennessee with 12–27 years in practice. In the quantitative phase, after applying all eligibility criteria, 100 RTT-treating physicians were considered eligible to participate in the survey. Physician characteristics are presented in . Surveyed physicians consisted of 51 neurologists and 49 pediatricians and had spent an average (SD) of 19 (9) years in their specialty post-residency. A large proportion of neurologists were based in academic/university medical centers (43%) while most pediatricians worked in private practice (67%).

Table 1. Physician characteristicsTable Footnotea.

Physicians’ experience managing individuals with RTT

Physicians’ experience managing RTT has been shown in . Neurologists treated more individuals with RTT than pediatricians throughout their career (median: 12 vs. 5 individuals, p < 0.001) and in the past two years (median: 5 vs. 2 individuals, p < 0.001; ). Among individuals with RTT in a physician’s care, 42% were newly diagnosed by the RTT-treating physician, including among neurologists and pediatricians (neurologists: 42%; pediatricians: 42%; p = 0.538). A total of 40% of individuals had their diagnosis confirmed by the RTT-treating physician; a numerically higher proportion of individuals had their diagnosis confirmed by a pediatrician than a neurologist, although this difference did not attain statistical significance (neurologists: 33%; pediatricians: 50%; p = 0.058; ). Prior to completing the survey, overall physicians’ median time since their most recent encounter treating an individual with RTT was 3 months ago, with a significantly longer median time observed for pediatricians than for neurologists (6 vs. 2 months, p < 0.001). The longest median duration caring for an individual with RTT was 6 years (neurologists vs. pediatricians: median of 6 vs. 5 years, p = 0.231; ). In terms of their comfort level managing individuals with RTT, neurologists were more likely to report feeling “very comfortable” as compared with pediatricians (31 vs. 4%, p < 0.001; ).

Table 2. Physician experience managing individuals with RTT.

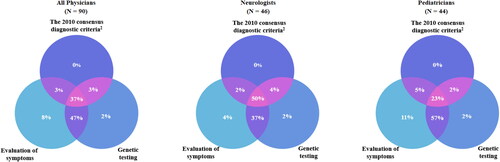

Most physicians (93%) had experience diagnosing RTT. Among physicians who had either newly assigned or confirmed a RTT diagnosis, neurologists had diagnosed an individual with RTT more recently than pediatricians had prior to the survey (median of 1 vs. 2 years ago, p < 0.001; ). Nearly all physicians (91%) evaluated symptoms to diagnose RTT, including most neurologists and pediatricians (90 vs. 93%; p = 0.845). Most physicians (86%) also used genetic testing as criteria for confirming a RTT diagnosis, with no significant difference in the use of genetic testing between neurologists and pediatricians (90 vs. 82%; p = 0.271). However, neurologists were almost twice as likely as pediatricians to use the 2010 consensus diagnostic criteria (54 vs. 29%, p = 0.012; ). All three diagnostic criteria/tests to assign/confirm RTT diagnosis were used by 50% of neurologists and 23% of pediatricians (). A combination of symptom evaluation and genetic testing was used by 37% of neurologists and 57% of pediatricians (). Evaluation of symptoms alone was used by 4% of neurologists and 11% of pediatricians (). At diagnosis, neurologists reportedly assigned a RTT classification more often than pediatricians (48 vs. 20%, p < 0.001; ). Among physicians with experience diagnosing RTT, most (87%) typically considered an alternative diagnosis, with the most common differential diagnoses being autism spectrum disorder (all physicians: 86%; neurologists: 81%; pediatricians: 92%; p = 0.458), non-specific developmental delay (61%; 52 vs. 69%; p = 0.232), and Angelman syndrome (54%; 60 vs. 49%; p = 0.302). Neurologists were more likely than pediatricians to additionally consider rarer diagnoses such as CDKL5 mutation (55 vs. 13%; p < 0.001; ).

Figure 1. Diagnostic criteria/tests used to assign/confirm RTT DiagnosisCitation1. Abbreviations. N, sample size; RTT, Rett syndrome Notes: 190/93 physicians with experience diagnosing RTT used the 2010 diagnostic criteria, symptom evaluation, and genetic testing, alone or in combination, for RTT diagnoses. Other diagnostic strategies used by physicians to diagnose RTT included diagnostic tools such as imaging, other diagnostic guidelines, and consultation with/referral to other specialists (data not shown). 2Neul et al. Rett syndrome: revised diagnostic criteria and nomenclature. Ann Neurol. 2010 Dec;68(6):944–50.

Therapeutic goals

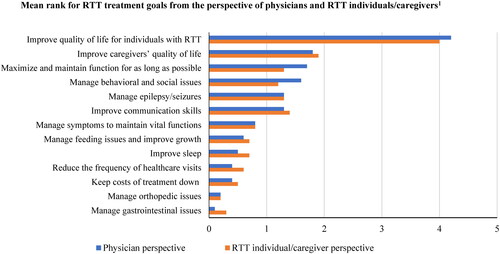

From both the physician perspective, as well as physician reports of the perspectives of individuals with RTT or caregivers of RTT, improving the quality of life (QOL) of individuals with RTT was the most important therapeutic goal, followed by improving caregivers’ QOL (; Supplementary Table S1). For physicians, other important goals included maximizing and maintaining function for as long as possible and managing the behavioral and social issues of individuals with RTT (). Based on physician reports, other important goals for individuals with RTT or their caregivers included improving the communication skills of individuals with RTT ().

Figure 2. RTT therapeutic goals from the perspectives of physicians and individuals with RTT/caregivers. Abbreviation. RTT, Rett syndrome Note: 1Physicians provided a rank to these therapeutic goals by importance. Each physician ranked up to five goals from 1 to 5, with 5 being the most important goal and 1 being the fifth most important goal. Therapeutic goals not ranked were given a score of 0.

Real-world management strategies among individuals with RTT

Physicians monitored progress primarily using clinical practice guidelines (60%). In addition, 18–34% of physicians used clinical scales such as the RTT Clinical Severity Scale (CSS), Rett Syndrome Behaviour Questionnaire (RSBQ), and Motor Behavior Assessment scale (MBA; ). Although use of the CSS (41 vs. 27%, p = 0.122), RSBQ (28 vs. 22%, p = 0.564), and MBA (24 vs. 12%, p = 0.142) was numerically higher among neurologists than pediatricians, differences were not statistically significant. With respect to factors considered when recommending therapies for symptom control, age of the individual with RTT (80%), disease stage (76%), and RTT individual/family preference (71%) were key factors considered by physicians for therapeutic decisions. Numerically, more neurologists considered price/cost of therapy, frequency and duration of administration of the therapy, and route of administration than pediatricians, whereas numerically, more pediatricians considered the age of the individual with RTT and RTT individual/family preference than neurologists, although differences were not statistically significant ().

Table 3. Overall management of individuals with RTT.

The top three symptoms that physicians most treated among individuals with RTT were behavioral issues (67%), epilepsy and seizures (63%), and feeding issues (33%; Supplementary Table S2). For all symptoms, physicians identified referral to the appropriate specialist as a common management strategy; nonetheless, typical management strategies varied by symptom (Supplementary Table S2). Pharmacological therapies were commonly used to treat behavioral issues, epilepsy/seizures, constipation, neuromuscular issues, and sleep difficulties (e.g. anti-seizure/antiepileptic medications, anti-anxiety medications, muscle relaxants, laxatives, sleep medications, etc.). Non-pharmacologic strategies, such as occupational therapy, speech therapy, and physical therapy, were commonly used to manage symptoms such as feeding issues, loss of communication skills, neuromuscular issues, and loss of or problems with gross motor skills. Other commonly used non-pharmacologic strategies included dietary interventions and supplements for epilepsy/seizures, feeding issues, constipation, and growth abnormalities, and hormonal supplements for sleep difficulties. Medical equipment/devices were commonly used for managing loss of communication skills, neuromuscular issues, and loss of or problems with gross motor skills (e.g. augmentative and alternative communication devices, orthotics, wheelchair, etc.; Supplementary Table S2). When asked about the greatest areas of unmet need for individuals with RTT today, 37% of physicians who responded to the question identified the lack of novel therapies and reliance on symptom-specific management as an unmet need (Supplementary Table S3).

Discussion

In this cross-sectional survey study, RTT-treating physicians in the US reported on their experience managing individuals with RTT, including their decision-making regarding therapeutic goals and management strategies. Our study found that neurologists have more experience managing RTT, as they tend to be affiliated with larger academic practices than pediatricians, have treated more individuals with RTT, have had more recent encounters, and are more comfortable managing individuals with RTT. Most physicians had experience diagnosing RTT, primarily through symptom evaluation. However, neurologists were more likely than pediatricians to use the 2010 consensus diagnostic criteria when diagnosing individuals with RTT. The most important therapeutic goals among physicians were improving QOL among individuals with RTT as well as among their caregivers. Most physicians used clinical practice guidelines to monitor the progress of individuals with RTT, although numerically more neurologists relied on clinical scales such as the CSS, RSBQ, and MBA than pediatricians. Among all physicians, the top three most treated symptoms were behavioral issues, epilepsy/seizures, and feeding issues. Therapeutic strategies varied by symptom, with referral to the appropriate specialists cited as an important management strategy. More than a third of physicians identified the lack of novel therapies and reliance on symptom-specific management as an unmet need.

Given a dearth of published studies reporting on physician experience and approaches to diagnosing and managing RTT in routine clinical practice, this study helps to fill an important knowledge gap in the literature. In particular, the present findings highlight the need for greater awareness of RTT and education on RTT diagnosis and management among pediatric healthcare professionals. We note that a primary responsibility of pediatricians is general developmental surveillance, namely, to detect any potential signs of abnormal development early on so that the individual can be referred to the appropriate specialist (e.g. a neurologist) for further assessment and diagnosisCitation14,Citation19. Ideally, pediatricians should detect these signs in a timely manner to ensure early diagnosis and management. Nonetheless, even with respect to developmental disorders overall, rates of detection have been historically lower than the actual prevalenceCitation14. This reflects the broader challenge pediatricians face when having to screen individuals for developmental disorders in a timely manner using effective, standardized methodsCitation14,Citation19. In 2006, this prompted the Council on Children With Disabilities to provide an algorithm to support pediatricians and other healthcare providers in detecting developmental disorders at early agesCitation14. In addition to these broad screening tools, other guidelines have been developed to help pediatricians identify signs of specific developmental disorders (e.g. autism spectrum disorder, neuromotor disorders, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and various behavioral conditions). Awareness of RTT has improved among pediatricians over time, as evidenced by increased use of broad developmental screening tools (from 21% of pediatricians in 2002 to 63% in 2016)Citation20 and greater frequency of classic RTT diagnosesCitation15. Despite this progress, universal screening has not been achieved among pediatricians. Therefore, in 2020, the AAP proposed a continuation of unified national efforts to increase early screening and detection rates and to expand the evidence base for the development of improved developmental surveillance and screening methods. To address the latter point, the 2020 AAP policy statement proposed a universal system of screening for the full range of neurodevelopmental and behavioral conditions among all children in the primary care settingCitation19,Citation20. Moreover, the 2020 consensus-based guidelines for managing communication in individuals with RTT have strongly encouraged healthcare professionals who are less experienced in managing individuals with RTT to seek training in relevant topics and support from more specialized colleaguesCitation7,Citation37,Citation38. By highlighting the potential gaps in awareness of RTT among pediatricians, our findings are broadly consistent with the above policy statements and suggest potential areas where pediatricians could refine their knowledge. Further, the present findings might help to inform the development of better standardized surveillance and screening methods. While RTT is a rare condition, greater awareness among pediatricians would be beneficial to individuals with RTT and their caregivers.

The current consensus is that diagnosis of RTT should be primarily based on the presence of distinct clinical features as outlined in the 2010 revised diagnostic criteriaCitation9. These recommendations are informed by evidence that 3–5% of individuals who meet the strict clinical criteria for RTT do not have an identified mutation in MECP2, thus a mutation in this gene is not necessary to make the diagnosis of typical RTTCitation9. Consistent with this, almost all physicians in our study used the evaluation of symptoms to diagnose RTT, although most also used genetic testing. Pediatricians were half as likely as neurologists to use the 2010 diagnostic criteria to identify individuals with RTT, which appears consistent with the results of the AAP survey showing that about 70% of pediatricians almost exclusively relied on clinical assessments without any standardized approachCitation16. According to the 2010 consensus diagnostic criteria, alternative diagnoses besides RTT should also be explored when assessing individuals, as mutations in MECP2 have been associated with other neurodevelopmental conditions such as autism, Angelman syndrome-like presentation, and non-specific intellectual disabilityCitation9. Consistent with this, among physicians with experience diagnosing RTT in our study, most (87%) considered alternative diagnoses, although neurologists were more likely than pediatricians to also consider rare diagnoses. This further highlights the need for increased awareness and education on RTT diagnosis among pediatricians.

Important therapeutic goals from the perspectives of physicians in our study were to improve QOL for individuals with RTT, to manage their behavioral and social issues, and to maximize and maintain their function for as long as possible. Consistent with this, the 2020 consensus guidelines on managing RTT encourage early initiation and continued use of interventions aimed at improving QOL for individuals with RTT and facilitating the transition to adulthoodCitation7. For instance, recommended approaches include early referral to specialists (e.g. physical therapists, occupational therapists, speech language therapists, etc.) and individualized education programs, as well as day programs and respite care to ease the transition to adulthoodCitation7. It is also notable that physicians in our study recognized improving caregivers’ QOL as the second most important goal of therapy. Indeed, the day-to-day challenges of managing individuals with RTT have been previously documented in several studies of RTT caregiver burdenCitation22,Citation39–41. In qualitative studies, caregivers have spoken of the frustrations associated with delays in diagnosis, frequent testing, and the “continuous struggle” to access the necessary resources in both health and social careCitation22,Citation39. In a systematic review of QOL among those affected by RTT, these complex medical needs were found to negatively affect the physical, psychological, and social dimensions among individuals with RTT and their family members; among parents, the dimensions most affected were those related to mental health and well-beingCitation40. Prior evidence suggests that epilepsy/seizures are a major factor driving this reduced QOL among caregiversCitation41, along with constipation, feeding problems, and behavioral and communication problemsCitation40. Although physicians in our study recognized the management of these symptoms as important, a greater focus on these therapeutic goals may be key to improving QOL among individuals with RTT and their caregivers.

Our study found that RTT-treating physicians commonly used pharmacological strategies to treat behavioral issues, epilepsy/seizures, constipation, neuromuscular issues, and sleep difficulties. These strategies are generally aligned with the 2020 consensus guidelines on the management and monitoring of RTT, which recommend use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for anxiety or depression, anticonvulsants for epilepsy/seizure (accompanied by follow-up every 6 months), laxatives for constipation, neuromuscular blockade or other medications for neuromuscular issues, and trazodone or clonidine for sleep difficultiesCitation7. Also consistent with our findings, the consensus guidelines recommend the use of non-pharmacological strategies for symptom management, including occupational, physical, and speech therapy to improve mobility, communication, and socializationCitation7. Additional recommendations include augmentative technologies for improving communication skills (e.g. eye gaze technologies, symbol communication boards, etc.) and the use of supplements (e.g. melatonin for sleep)Citation7, which were also used by RTT-treating physicians in the present study. Beyond these strategies, referral to appropriate specialists was commonly used to manage most symptoms. In general, our findings suggest that physicians employ a holistic approach to managing RTT symptoms that is aligned with current best practices. However, this highlights that individuals with RTT need complex care, with coordination of a range of symptom-specific therapeutic strategies and multiple specialist referrals, potentially increasing the healthcare burden experienced by both individuals and their families, as well as the healthcare system. Thus, as indicated by over a third of the physicians, there is a critical need for novel therapies or targeted drugs that could treat multiple symptoms in parallel while minimizing the inconvenience and risk of adverse events typically associated with polypharmacy, thereby helping to streamline the management of RTTCitation42. Such novel therapies would also be essential for improving QOL among individuals with RTT and their caregivers, especially considering the long duration of time that individuals with RTT live with debilitating symptoms and complications.

This study may have been subject to certain limitations inherent to qualitative and quantitative approaches. During the qualitative phase, in-depth interviews might not have addressed all relevant topics, and a broad range of experiences and perspectives might not have been captured due to the small sample size. To mitigate these potential limitations, information collected during the first two interviews with the KOLs were used to inform the subsequent interviews with the remaining three physicians. During the quantitative phase, survey questions may have been subject to differing interpretations by respondents, although a draft survey instrument was pre-tested to minimize the impact of this limitation. The study also relied on physicians’ experience treating individuals with RTT when reporting data, which could be subject to recall error. Additionally, the results of the survey may not be generalizable to physicians outside of the sample studied. To address this potential limitation, the study surveyed 100 physicians from a range of geographic regions and backgrounds (including both pediatricians and neurologists).

Conclusions

This study describes physician decision-making regarding therapeutic goals and real-world management strategies among individuals with RTT in the US. The results indicate that individuals with RTT experience a wide range of clinical complications, which are typically managed using symptom-specific strategies. Our findings suggest that better education and support for pediatricians, who are among the main care providers for individuals with RTT, is important for improving clinical outcomes. Furthermore, our findings underscore the lack of novel treatments for RTT that can address multiple symptoms concurrently as an important unmet need. Such treatments could help to reduce the complexity of care among physicians and significantly improve QOL among individuals with RTT and their caregivers. More recently, several clinical trials of novel or existing agents for the treatment of RTT have been ongoing or completedCitation27,Citation42,Citation43, which could potentially alleviate the burden of disease. Given the changing treatment landscape and management strategies for RTT, it will be critical for future studies to identify and describe clear metrics of treatment success, especially in terms of the burden on individuals with RTT and their caregivers.

Transparency

Author contributions

DMM, JLN, AS, WYC, PL, JEPG were involved in the conception and design. AS, WYC, NL, AB, and PL were involved in the analysis and interpretation of the data. AS, WYC, NL, and AB were involved in the drafting of the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript critically for intellectual content and approved the final version to be published. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have received an honorarium from JME for their review work but have no other relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Previous presentations

Part of the data in this paper was presented at the Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy 2023 Meeting in San Antonio, TX, from 21–24 March 2023 as a poster presentation.

IRB approval number

21-ANGR-104 (reviewed by Pearl IRB).

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (56 KB)Acknowledgements

Medical writing and editorial assistance was provided by Mona Lisa Chanda, Ph.D., a professional medical writer employed by Analysis Group, Inc. Support for this assistance was provided by Acadia Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Declaration of funding

This study was sponsored by Acadia Pharmaceuticals, Inc. All authors from Acadia met the ICJME criteria for publication as defined by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

JLN has received research funding from the National Institutes of Health, the International Rett Syndrome Foundation, and Rett Syndrome Research Trust; personal consultancy for Acadia Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Analysis Group, Inc, AveXis, GW Pharmaceuticals, Hoffmann-La Roche, Myrtelle, Neurogene, Newron Pharmaceuticals, Signant Health, and Taysha Gene Therapies; serves on the scientific advisory board of Alcyone Lifesciences; is a scientific cofounder of LizarBio Therapeutics; and was a member of a data safety monitoring board for clinical trials conducted by Ovid Therapeutics. DMM is an employee of Acadia Pharmaceuticals, Inc. AS, NL, AB, and PL are current employees of Analysis Group, Inc., a consultancy that received funding from Acadia Pharmaceuticals, Inc., to conduct this study. WYC was an employee of Analysis Group, Inc. at the time this study was conducted. JEPG is a Consultant and Speaker for Aquestive pharmaceuticals, Eisai, SK Life Science, UCB Pharma, Neurelis and a Consultant for Analysis Group.

References

- Laurvick CL, de Klerk N, Bower C, et al. Rett syndrome in Australia: a review of the epidemiology. J Pediatr. 2006;148(3):347–352. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.10.037.

- Weaving L, Ellaway C, Gecz J, et al. Rett syndrome: clinical review and genetic update. J Med Genet. 2005;42(1):1–7. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.027730.

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Rett syndrome fact sheet 2020; 2021 [cited 2021 Apr 27]. Available from: https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/Patient-Caregiver-Education/Fact-Sheets/Rett-Syndrome-Fact-Sheet.

- Cuddapah VA, Pillai RB, Shekar KV, et al. Methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 (MECP2) mutation type is associated with disease severity in Rett syndrome. J Med Genet. 2014;51(3):152–158. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2013-102113.

- Collins BE, Neul JL. Rett syndrome and MECP2 duplication syndrome: disorders of MeCP2 dosage. NDT. 2022;18:2813–2835. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S371483.

- Hagberg B, Goutieres F, Hanefeld F, et al. Rett syndrome: criteria for inclusion and exclusion. Brain Dev. 1985;7(3):372–373. doi: 10.1016/S0387-7604(85)80048-6.

- Fu C, Armstrong D, Marsh E, et al. Consensus guidelines on managing Rett syndrome across the lifespan. BMJPO. 2020;4(1):e000717. doi: 10.1136/bmjpo-2020-000717.

- Hagberg B, Aicardi J, Dias K, et al. A progressive syndrome of autism, dementia, ataxia, and loss of purposeful hand use in girls: Rett’s syndrome: report of 35 cases. Ann Neurol. 1983;14(4):471–479. doi: 10.1002/ana.410140412.

- Neul JL, Kaufmann WE, Glaze DG, et al. Rett syndrome: revised diagnostic criteria and nomenclature. Ann Neurol. 2010;68(6):944–950. doi: 10.1002/ana.22124.

- Cosentino L, Vigli D, Franchi F, et al. Rett syndrome before regression: a time window of overlooked opportunities for diagnosis and intervention. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2019;107:115–135. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.05.013.

- Einspieler C, Marschik PB. Regression in Rett syndrome: developmental pathways to its onset. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2019;98:320–332. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.01.028.

- Kerr AM. Early clinical signs in the Rett disorder. Neuropediatrics. 1995;26(02):67–71. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-979725.

- Pokorny FB, Bartl-Pokorny KD, Einspieler C, et al. Typical vs. atypical: combining auditory gestalt perception and acoustic analysis of early vocalisations in Rett syndrome. Res Dev Disabil. 2018;82:109–119. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2018.02.019.

- Council on Children with Disabilities, Section on Developmental Behavioral Pediatrics, Bright Futures Steering Committee. Identifying infants and young children with developmental disorders in the medical home: an algorithm for developmental surveillance and screening. Pediatrics. 2006;118(1):405–420. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1231.

- Tarquinio DC, Hou W, Neul JL, et al. Age of diagnosis in Rett syndrome: patterns of recognition among diagnosticians and risk factors for late diagnosis. Pediatr Neurol. 2015;52(6):585–591 e2. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2015.02.007.

- Sand N, Silverstein M, Glascoe FP, et al. Pediatricians’ reported practices regarding developmental screening: do guidelines work? Do they help? Pediatrics. 2005;116(1):174–179. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1809.

- Hagberg B, Hanefeld F, Percy A, et al. An update on clinically applicable diagnostic criteria in Rett syndrome. Comments to Rett syndrome clinical criteria consensus panel satellite to European Paediatric Neurology Society meeting, Baden Baden, Germany, 11 September 2001. EJPN. 2002;6(5):293–297. doi: 10.1053/ejpn.2002.0612.

- Hagberg B. Clinical manifestations and stages of Rett syndrome. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2002;8(2):61–65. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.10020.

- Lipkin PH, Macias MM, Norwood KW Jr, et al. Promoting optimal development: identifying infants and young children with developmental disorders through developmental surveillance and screening. Pediatrics. 2020;145(1):e20193449. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3449.

- Lipkin PH, Macias MM, Baer Chen B, et al. Trends in pediatricians’ developmental screening: 2002–2016. Pediatrics. 2020;145(4):e20190851. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0851.

- Fu C, Armstrong D, Marsh E, et al. Multisystem comorbidities in classic Rett syndrome: a scoping review. BMJPO. 2020;4(1):e000731-e000731. doi: 10.1136/bmjpo-2020-000731.

- Güeita-Rodriguez J, Famoso-Pérez P, Salom-Moreno J, et al. Challenges affecting access to health and social care resources and time management among parents of children with Rett syndrome: a qualitative case study. IJERPH. 2020;17(12):4466. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17124466.

- Banerjee A, Miller MT, Li K, et al. Towards a better diagnosis and treatment of Rett syndrome: a model synaptic disorder. Brain. 2019;142(2):239–248. doi: 10.1093/brain/awy323.

- Mackay J, Downs J, Wong K, et al. Autonomic breathing abnormalities in rett syndrome: caregiver perspectives in an international database study. J Neurodevelop Disord. 2017;9(1):1–13. doi: 10.1186/s11689-017-9196-7.

- Oddy WH, Webb KG, Baikie G, et al. Feeding experiences and growth status in a Rett syndrome population. J Pediat Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;45(5):582–590. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e318073cbf7.

- Downs J, Bergman A, Carter P, et al. Guidelines for management of scoliosis in Rett syndrome patients based on expert consensus and clinical evidence. Spine. 2009;34(17):E607–E617. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181a95ca4.

- Sandweiss AJ, Brandt VL, Zoghbi HY. Advances in understanding of Rett syndrome and MECP2 duplication syndrome: prospects for future therapies. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(8):689–698. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30217-9.

- Romano A, Capri T, Semino M, et al. Gross motor, physical activity and musculoskeletal disorder evaluation tools for Rett syndrome: a systematic review. Dev Neurorehabil. 2020;23(8):485–501. doi: 10.1080/17518423.2019.1680761.

- Amoako AN, Hare DJ. Non-medical interventions for individuals with Rett syndrome: a systematic review. Research Intellect Disabil. 2020;33(5):808–827. doi: 10.1111/jar.12694.

- Neul JL, Percy AK, Benke TA, et al. Trofinetide for the treatment of Rett syndrome: a randomized phase 3 study. Nat Med. 2023;29(6):1468–1475. doi: 10.1038/s41591-023-02398-1.

- United States Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves first treatment for Rett syndrome; 2023 [cited 2023 Sep 1]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/news-events-human-drugs/fda-approves-first-treatment-rett-syndrome.

- Millichap JG. Risk factors for late diagnosis of Rett syndrome. Pediatr Neurol Briefs. 2015;29(5):38. doi: 10.15844/pedneurbriefs-29-5-5.

- Fehr S, Bebbington A, Nassar N, et al. Trends in the diagnosis of Rett syndrome in Australia. Pediatr Res. 2011;70(3):313–319. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3182242461.

- Greene JC, Caracelli VJ, Graham WF. Toward a conceptual framework for mixed-method evaluation designs. Educat Eval Pol Anal. 1989;11(3):255–274. doi: 10.3102/01623737011003255.

- Bryman A. Integrating quantitative and qualitative research: how is it done? Qualit Res. 2006;6(1):97–113. doi: 10.1177/1468794106058877.

- Migiro SO, Magangi BA. Mixed methods: a review of literature and the future of the new research paradigm. Afr J Busi Manage. 2011;5(10):3757–3764.

- Townend GS, Bartolotta TE, Urbanowicz A, et al. Development of consensus-based guidelines for managing communication of individuals with Rett syndrome. Augment Altern Commun. 2020;36(2):71–81. doi: 10.1080/07434618.2020.1785009.

- Townend GS, Bartolotta TE, Urbanowicz A, et al. Rett syndrome communication guidelines: a handbook for therapists, educators and families. Maastricht, NL, and Rettsyndrome.org, Cincinnati, OH: Rett Expertise Centre Netherlands-GKC; 2020.

- Palacios-Cena D, Famoso-Perez P, Salom-Moreno J, et al. “Living an obstacle course": a qualitative study examining the experiences of caregivers of children with Rett syndrome. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;16(1):41.

- Corchón S, Carrillo-López I, Cauli O. Quality of life related to clinical features in patients with Rett syndrome and their parents: a systematic review. Metab Brain Dis. 2018;33(6):1801–1810. doi: 10.1007/s11011-018-0316-1.

- Mori Y, Downs J, Wong K, et al. Longitudinal effects of caregiving on parental well-being: the example of Rett syndrome, a severe neurological disorder. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019;28(4):505–520. doi: 10.1007/s00787-018-1214-0.

- Ivy AS, Standridge SM. Rett syndrome: a timely review from recognition to current clinical approaches and clinical study updates. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2021;37:100881. doi: 10.1016/j.spen.2021.100881.

- Glaze DG, Neul JL, Percy A, et al. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical study of trofinetide in the treatment of Rett syndrome. Pediat Neurol. 2017;76:37–46. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2017.07.002.