Abstract

Aim

This study aimed to examine the validity of EQ-5D-5L among HFrEF patients in Malaysia, and to explore the measurement equivalence of three main language versions.

Methods

We surveyed HFrEF patients from two hospitals in Malaysia, using Malay, English or Chinese versions of EQ-5D-5L. EQ-5D-5L dimensional scores were converted to utility scores using the Malaysian value set. A confirmatory factor analysis longitudinal model was constructed. The utility and visual analog scale (VAS) scores were evaluated for validity (convergent, known-group, responsiveness), and measurement equivalence of the three language versions.

Results

200 HFrEF patients (mean age = 61 years), predominantly male (74%) of Malay ethnicity (55%), completed the admission and discharge EQ-5D-5L questionnaire in Malay (49%), English (26%) or Chinese (25%) languages. 173 patients (86.5%) were followed up at 1-month post-discharge (1MPD). The standardized factor loadings and average variance extracted were ≥ 0.5 while composite reliability was ≥ 0.7, suggesting convergent validity. Patients with older age and higher New York Heart Association (NYHA) class reported significantly lower utility and VAS scores. The change in utility and VAS scores between admission and discharge was large, while the change between discharge and 1MPD was minimal. The minimal clinically important difference for utility and VAS scores was ±0.19 and ±11.01, respectively. Malay and English questionnaire were equivalent while the equivalence of Malay and Chinese questionnaire was inconclusive.

Limitation

This study only sampled HFrEF patients from two teaching hospitals, thus limiting the generalizability of results to the entire heart failure population.

Conclusion

EQ-5D-5L is a valid questionnaire to measure health-related quality of life and estimate utility values among HFrEF patients in Malaysia. The Malay and English versions of EQ-5D-5L appear equivalent for clinical and economic assessments.

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY

EQ-5D is the most commonly used questionnaire to measure patients’ health-related quality of life in clinical trials and health technology assessments. To increase confidence over clinical trial findings that heart failure interventions improve health-related quality of life and quality-adjusted life years (number of years alive with equivalence health-related quality of life), the questionnaire used to measure health-related quality of life needs to be validated in the specific population. Since EQ-5D-5L has not been validated in Malaysia’s heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) population, this study evaluated the psychometric properties (validity) of EQ-5D-5L among HFrEF patients in Malaysia and the equivalence of different versions of languages (i.e. Malay, Chinese and English) of EQ-5D-5L in measuring the health-related quality of life. The findings suggested that EQ-5D-5L is a valid questionnaire to measure the health-related quality of life in HFrEF patients and estimate the quality-adjusted life years. The Malay and English versions of EQ-5D-5L appear to be equivalent for use in clinical trials and health technology assessments.

Introduction

In Malaysia, the prevalence of heart failure (HF) is one of the highest worldwide (6.7%)Citation1 and HF accounted for about 6-10% of all acute admissionsCitation2. HF is not only associated with high mortality but debilitating physical symptoms including shortness of breath, fatigue, physical limitations, and sleeping difficulties, which affect patients’ psychological, social, and spiritual well-beingCitation3. Studies also showed that the health-related quality of life (HRQoL) of HF patients was the worst among other cardiovascular diseasesCitation4,Citation5. Besides symptoms burden, hospitalization due to worsening of HF also places considerable stress to HF patients, markedly reducing their HRQoLCitation6,Citation7. Therefore, the three major treatment goals for HF patients include reduction in mortality, prevention of recurrent hospitalizations, and improvement in clinical symptoms, functional capacity, and HRQoLCitation2,Citation8,Citation9.

EQ-5D questionnaire is the most commonly used patient-reported outcome measure (PROM) to measure HRQoL in clinical trials as it exhibits excellent psychometric properties across a broad range of populations and conditions including cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, lung, cancer, musculoskeletal/orthopedic, mental health and autoimmune conditionsCitation10. Many pharmacoeconomic guidelines and health technology assessment (HTA) authorities also recommended the use of EQ-5D in estimating utility value and subsequent quality-adjusted life-years for technology adoption decisionsCitation11–13. While HRQoL is influenced by many factors, including socio-cultural characteristics, variations in life experiences, adaptation to suboptimal health conditions and healthcare costsCitation14–16, psychometric testing of EQ-5D in a given socio-cultural setting and disease-specific population is important to improve the validity of future clinical and economic evaluations, enabling patient-centric healthcare decisionsCitation17,Citation18.

EQ-5D-5L has been validated in the German HF populationCitation19. In Malaysia, despite EQ-5D-5L being validated in the general populationCitation20 and other disease populationsCitation21,Citation22, the psychometric properties of EQ-5D-5L among the heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) population in Malaysia and the subsequent mapping of utility values remained unclear. Given the frequent use of EQ-5D-5L in HFrEF research studies including clinical trials and economic evaluationsCitation23,Citation24 and reviews have shown that utility was one of the model drivers and a source of heterogeneity in HFrEF economic evaluationsCitation24–26, this study aimed to examine the validity of EQ-5D-5L in measuring HRQoL and estimating utility values among HFrEF patients in Malaysia.

Besides that, although four languages of EQ-5D-3L (Malay, English, Chinese, and Tamil) have been validated through construct and content validation in MalaysiaCitation27,Citation28, no study examined the measurement equivalence among different languages before being used in clinical trials and economic assessment. As Malaysia is a multi-cultural and multi-ethnicity country, evidence of measurement equivalence among different languages of EQ-5D-5L is essential to ensure the diversity of populations in future studies that evaluate HRQoL using EQ-5D-5L. Therefore, this study also explored the measurement equivalence of the Malay, English and Chinese versions of the EQ-5D-5L among HFrEF populations in Malaysia.

Methods

A prospective cohort study was conducted on HFrEF patients admitted into two teaching hospitals in Malaysia between June 2022 to April 2023. Key inclusion criteria included (1) patients aged ≥18 years old, (2) diagnosed with heart failure (ICD-10 diagnosis I50.9), (3) evidence of left ventricular ejection fraction ≤40%, and (4) hospitalized for more than 24 h with signs and symptoms of fluid overload, requiring intravenous diuretics. Exclusion criteria were (1) critically ill, (2) active contagious infection, (3) passed away during index hospitalization, and (4) unable to comprehend or provide consent (see detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria in Appendix 1). This study was conducted in accordance with STROBE and COSMIN guidance (see details in Appendix 2 and 3)Citation29,Citation30.

Convenience sampling was used to recruit patients based on patients’ willingness to participate until the minimum sample size (n = 50 for each language) was achieved. HRQoL was evaluated using EQ-5D-5L questionnaire, which comprised (1) five questions, encompassing five dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression, and (2) a visual analog scale (VAS), ranging from 100 (“the best imaginable health state” or “the best health state you can imagine”) to 0 (“the worst imaginable health state” or “the worst health you can imagine”). The Malay, English, and Chinese versions of EQ-5D-5L, developed through translations commissioned by the EuroQol Group, were used depending on participants’ preferences to ensure adequate representation of the study population based on the diversity of the Malaysian population. These three languages were selected because they are the most commonly used languages in Malaysia whereas the use of Tamil language in Malaysia has been largely dominated by English and Malay languageCitation31. The permission to use the three language versions has been obtained from EuroQol Group before data collection.

EQ-5D-5L data were collected at 3 time-points: admission, discharge and 1-month post-discharge (1MPD). These time-points were chosen because HRQoL could be impacted by hospitalizationCitation24,Citation32 and changes in health status were reported in HF population between discharge and 1-month post-dischargesCitation6,Citation33. Given that there was no significant difference in the HRQoL scores between self-completion and assisted-completion and between face-to-face and telephone interviewsCitation34, a mix-mode of administration was used to maximize response rates. Both admission and discharge EQ-5D-5L data were collected through face-to-face interviews and assisted with physical copies of questionnaire. 1-month post-discharge EQ-5D-5L data were collected through phone interviews by the same trained interviewers. The interviewers were trained to follow the scripted questionnaire to ensure consistency in eliciting HRQoL.

Further explanation or assistance was provided to the participants if needed. Eligible patients were asked for informed consent before data collection. Baseline demographics, clinical information, comorbidities, and medication history were obtained from the electronic medical records. All data were de-identified to protect patient confidentiality. Ethics approval has been granted by the ethics committees of the participating centers (202234-11050; REC/07/2022 (OT/MR/3); 32518).

Sample size

Given no clear recommendations on the sample size required for PROM validation studies, the sample size was determined using the rule of thumb (i.e. 5-10 participants for every item)Citation30,Citation35. As EQ-5D-5L questionnaire has five items with three language versions, the estimated sample size was 150 (50 for each language).

Statistical analysis

EQ-5D-5L dimensional scores (e.g. 11111) were converted to utility scores using published Malaysian population value sets, derived using the time trade-off methodCitation36. The Malaysian utility scores ranged from −0.442 (health state worse than death) to 1 (best health state), with “0” being the health state at death. The visual analog scale (VAS) is a 20 cm-length scale, ranging from 0 (worst health state) to 100 (best health state), and the scores represented the patients’ overall perceived health on the measurement day. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the baseline characteristics of participants and EQ-5D-5L outcomes. Comorbidities were summarized using Charlson’s Comorbidity Index (see Appendix 4). Categorical variables were examined using a chi-square/Fisher exact test. Continuous variables were compared with Kruskal-Wallis test. EQ-5D-5L validity (convergent known-group and responsiveness)and measurement equivalence (different languages) were tested based on the COSMIN checklistCitation30. Analyses were performed on complete cases using SPSS and R, with statistical significance set at a p < 0.05.

Floor and ceiling effects

Floor effects on the EQ-5D-5L were considered present when >15% of the patients at each measurement time-points reported “55555” (severe problem), and ceiling effects when >15% of the patients at each measurement time-points reported “11111” (no problem)Citation10,Citation20.

Validity

A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) longitudinal ordered-categorical model was constructed with HRQoL as the latent factor and EQ-5D-5L dimensions as the observed factors. As EQ-5D-5L dimensions were measured on an ordinal scale, a diagonal weighted least squaresCitation37 estimation method was used to measure standardized factor loadings, average variance extracted and composite reliabilityCitation38,Citation39. Convergent validity of EQ-5D-5L dimensions was assessed with standardized factor loadings and average variance extracted ≥ 0.50 as acceptable threshold whereas composite reliability with a value of ≥ 0.7 as acceptable thresholdCitation38.

Known-group validity of the utility scores was evaluated by comparing subgroups of patients known to differ in health status using linear mixed effects regression model (i.e. unadjusted, model 1 and model 2)Citation40,Citation41. The known groups were defined by age and NYHA. We hypothesized that older patients (≥60 years old) have lower HRQoL compared with younger patients (<60 years old) while patients with high NYHA class have reduced HRQoL compared to those with lower NYHA class (see details in Appendix 5)Citation40,Citation42. Model 1 was adjusted for language, rater, center and accounted for repeated measures and within-patient variance whereas Model 2 was adjusted for age, gender, ethnics, language, rater, center for each group and accounted for repeated measures and within-patient variance.

Responsiveness, also known as longitudinal validity, was measured in effect size (ES) and standard response mean (SRM). Both ES and SRM are standardized measures of change over time in health, independent of sample size and were classified according to Cohen’s rule of thumb, as large (≥0.8), moderate (0.5–0.79) or small (<0.5). It was hypothesized that there is a large change in utility and VAS scores between admission and discharge while the change between discharge and 1MPD is minimal. Minimal clinically important difference (MCID) was determined using distribution-based methodCitation43. Half-SD was computed at baseline while one-SEM was computed at admission, discharge, and follow-up respectively using mean intraclass coefficients (ICC) due to the absence of Malaysia-specific ICC (see formulae and details in Appendix 6). Sensitivity analyses were conducted using Brunei’s ICC to explore the uncertainty associated with ICCCitation44. The minimal detectable change (MDC) is the smallest detectable change after considering the measurement error at the individual level. The ratios of MCID to MDCg were calculated for half SD and one-SEM (MCID:MDC >1 indicates real minimal important change, instead of measurement error)Citation43.

Measurement equivalence

The equivalence of Malay, English and Chinese EQ-5D-5L questionnaire in deriving utility and VAS score was examined using the methodology for assessing therapeutic equivalence in clinical trialsCitation17,Citation45–48. Linear mixed models were used to estimate the between-language difference (Malay language was used as the reference language due to its established psychometric properties in MalaysiaCitation20,Citation28, with or without adjustment for the influence of variables which significantly differed among the three languages (i.e. age, gender, ethnics, marital status, Type 2 Diabetes, and prior percutaneous coronary intervention). In line with the commonly accepted practice of equivalence studiesCitation17,Citation45,Citation47,Citation48, 90% confidence interval (90% CI) of utility and VAS coefficient estimates were used to compare with the equivalence margins derived from the minimal clinically important difference (MCID). It was hypothesized that (1) English and Chinese EQ-5D-5L are equivalent to Malay version if the 90% CI of estimates are entirely within the equivalence margin, (2) English and Chinese EQ-5D-5L could be either equivalent or not-equivalent to the Malay version if 90% CI of estimates partially overlap with the equivalence margin, (3) English and Chinese EQ-5D-5L are not-equivalent to Malay version if 90% CI of estimates fall entirely outside of the equivalence marginCitation17,Citation46. Sensitivity analyses were conducted using different equivalence margins and 95% CI (see hypothesis diagram and sensitivity analyses in Appendix 7).

Results

Study demographics

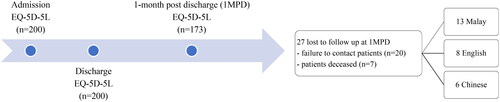

A total of 200 HFrEF patients completed admission and discharge EQ-5D-5L in Malay (49%, 98/200), English (26%, 52/200) and Chinese (25%, 50/200) languages. 173 patients (86.5%) completed 1-month post-discharge follow-up (see ).

Study demographics were described in . The mean age of study population was 61 ± 13.7 years old, predominantly male (74%), of Malay ethnicity (55%), with household income below USD1017 per month (92.5%), married (84.5%), and unemployed (73.5%). Most had recurrent HF hospitalization (67.5%), with HF diagnosis within a year (62.5%). The mean length of hospital stay was 5 ± 4.2 days. The overall median utility score was 0.09 (admission), 0.77 (discharge) and 0.85 (1MPD) while VAS score was 40 (admission), 70 (discharge) and 75 (1MPD).

Table 1. Baseline demographics of heart failure patients.

Floor and ceiling effects

No floor effect (“11111”) was observed at all three time-points. However, the ceiling effect (“55555”) was seen at discharge (17%) and 1MPD (27.5%).

Validity

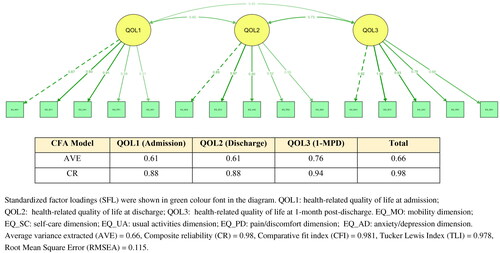

CFA model was presented in . The standardized factor loadings for all dimensions were acceptable, with anxiety and depression being the lowest loading, across the three time-points. Convergent validity was demonstrated with average variance extracted ≥ 0.5, and composite reliability ≥ 0.7.

For known-group validity, HFrEF patients in higher NYHA class have significantly lower utility and VAS scores and older HFrEF patients have significantly lower utility scores (). Unadjusted and adjusted models showed similar findings.

Table 2. Known group validity of EQ-5D-5L utility and VAS scores.

The change in utility and VAS scores between admission and discharge was large (ES and SRM ≥ 0.8), while the change in utility and VAS scores between discharge and 1MPD was small (ES and SRM < 0.5). The MCID for utility and VAS scores was ±0.19 and ±11.01, respectively. The MCID/MDC ratios were greater than 1 (), indicating a real minimal important change, instead of measurement error)Citation43. Sensitivity analysis using ICC of 0.626 (utility) and 0.521 (VAS) minimally increased the MCID to 0.21 (utility) and 12.18 (VAS) (Appendix 8).

Table 3. Responsiveness and minimal clinically important difference of EQ-5D-5L at different time-points.

Measurement equivalence

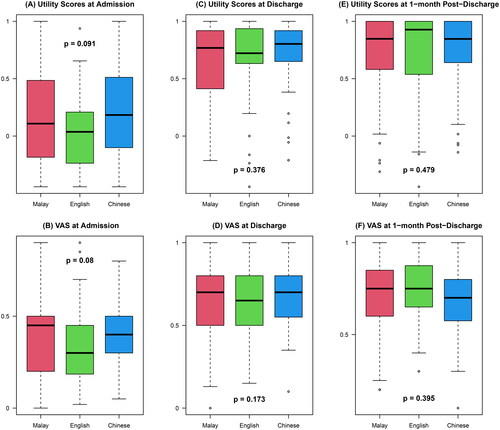

Using Kruskal-Wallis test, the utility and VAS scores were not statistically different (p > 0.05) among the three languages ().

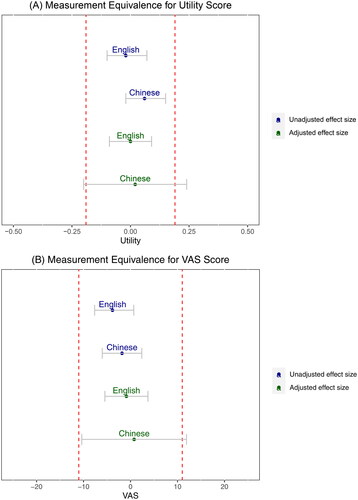

Using unadjusted linear mixed model, English and Chinese language were equivalent to Malay language in measuring utility and VAS scores, with the 90% confidence levels lie entirely within the equivalence margin for utility (−0.19, +0.19) and VAS scores (-11.01, +11.01). After adjusting for variables, the confidence interval of Chinese language marginally overlapped with the equivalence margins but the estimates were within the equivalence margin (). This suggested a potential but not conclusive measurement equivalence between Chinese and Malay language. Sensitivity analyses using different equivalence margins (based on MCIDs obtained from Brunei’s ICCs) and 95% confidence intervals suggested that the measurement equivalence of Malay and Chinese versions was sensitive to the equivalence margin and confidence intervals used (Appendix 9).

Discussion

Despite different languages of EQ-5D-5L being used in heart failure clinical trials in Malaysia, a multicultural and multi-ethnic setting, this is the first study to examine the validity of EQ-5D-5L and to explore the equivalence of Malay, English and Chinese versions of EQ-5D-5L in measuring HRQoL in Malaysia, providing evidence to support the use of different languages of EQ-5D-5L in HFrEF clinical trials and economic evaluations.

Consistent with many studiesCitation6,Citation19,Citation24,Citation40, our study confirmed that EQ-5D-5L is a valid PROM to measure the HRQoL among HFrEF patients in Malaysia. The observed large effect size between admission to discharge among HFrEF patients suggested that EQ-5D-5L has large responsiveness and is capable of capturing large impact of HF hospitalization on HRQoL of HFrEF patients. The observed ceiling effects at discharge and post-discharge, on the other hand, could be explained by acute HF hospitalization being a key source of distress for HFrEF patients and it substantially impacted patients’ HRQoLCitation24,Citation32,Citation49. Upon discharge, patients experienced a large improvement in symptoms and functional capacity, and this allowed immediate comparison in terms of HRQoL. Given that ceiling effect was the common inherent limitation of EQ-5D which applied to many other populationsCitation10, disease-specific PROMs such as Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) should be routinely administered in clinical settings, alongside EQ-5D (a generic PROM).

This study focused on validating EQ-5D-5L because EQ-5D-5L is the PROM recommended in Malaysia Pharmacoeconomics Guidelines for economic evaluationsCitation13. Using a generic PROM allows estimation of a standardized parameter (i.e. quality-adjusted life years) and eases direct comparison between diseases during technology adoption decisions. Secondly, there was an established value set, allowing direct mapping of EQ-5D-5L response into a single utility value in Malaysia and hence quantification of HRQoL whereas KCCQ mapping into EQ-5D-5L and utility values is non-linear and the changes in utility values may not map perfectly with KCCQCitation50. Lastly, EQ-5D-5L is often used in multinational heart failure clinical trials, validation of EQ-5D-5L in this disease population improves the validity of the trial outcomes.

Evidence showing measurement equivalence for different languages of EQ-5D-5L is also essential as it allows the inclusion of all ethnicities and cultures in any clinical trials or economic evaluations involving EQ-5D-5L, regardless of language barrier. Consistent with Wang et al. from SingaporeCitation17, our linear mixed models (both adjusted and unadjusted) found measurement equivalence between the Malay and English versions of EQ-5D-5L. On the other hand, comparing Malay and Chinese versions of EQ-5D-5L, the unadjusted model showed that Malay is equivalent to Chinese in estimating both utility and VAS scores whereas the adjusted model could not determine the equivalence between Malay and Chinese versions. The fact that the Chinese versions were all responded by Chinese patients and Chinese was more likely to endure health problems than other ethnicitiesCitation17,Citation51 suggested that there could be other confounding factors related to cultural, educational or socioeconomic status influencing the HRQoL that were not adjusted in this model. This warrants further studies on the differences in health-related quality of life between Chinese and other ethnicities. Studies with larger sample size can be considered to determine the equivalence, in view of high variability in the utility and VAS score for the Chinese language as observed from the large confidence intervals. Value of information analysis can also be applied to assess whether resources should be allocated to repeat the study with a larger sample size.

We used the MCID estimated in this study as the equivalence margin for the non-inferiority comparison and measurement equivalence tests. The large MCID and the finding of Malay and Chinese equivalence tests was sensitive to the equivalence margins and confidence intervals warrant a test-retest reliability study to estimate the country-specific ICC to improve the precision of equivalence margins and thus the measurement equivalence.

Given that Malaysia is a multi-cultural and multi-ethnicity country, future studies should not be refrained from using different versions of languages of EQ-5D-5L questionnaire but to include language as one of the confounding factors and adjust for language in the analysis. This prevents inequality and underrepresentation of certain population in future research studies including clinical trials, observational studies and registries that used EQ-5D-5L, diversifying the populations and accounting for different social determinants in the HRQoL outcomes.

Study limitations

First, this study only sampled HFrEF patients from two teaching hospitals, and this limited the generalizability of results to the entire Malaysian HF population, particularly heart failure patients with mid-range ejection fractions (HFmrEF) and heart failure patients with preserved ejection fractions (HFpEF) and the higher-income group or privately-insured patients who often do not present to the teaching hospitals. Future studies could validate EQ-5D-5L questionnaire among HFpEF patients and include other centers to verify this study finding. Second, the convenience sampling may have led to selection bias, as patients with poorer health could be less willing to participate and patients who passed away during the index hospitalization were not included in the study. However, based on the follow-up NYHA, it was observed that all severity groups were included in the study. Third, our sample size for each language is relatively small to be conclusive. Therefore, we used linear mixed model approach to utilise all available information and increase the number of observations. Besides that, the linear mixed model accounted for repeated measurements and within-patient correlations, increasing the precision and reducing biasCitation42,Citation46,Citation52. Lastly, this study assumed missing data occurred randomly and analyzed the data using complete cases, which could potentially introduce bias. The small loss to follow-up at 1MPD and similar findings observed at discharge and 1MPD suggested that the study findings were likely not influenced by missing data.

Conclusion

EQ-5D-5L is an appealing PROM for measuring the HRQoL in a multi-cultural and multi-ethnicity Malaysian population with HFrEF. The utility estimates derived from EQ-5D-5L and Malaysian tariffs are valid, providing prognostic stratification for HFrEF patients in Malaysia. Malay and English versions of EQ-5D-5L appear to be equivalent in eliciting the utility value of HFrEF patients for clinical and economic assessments.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

No funding is available for this study.

Author contributions

WCK: Study conceptualization and planning, data collection, data curation, data analysis and interpretation, and manuscript writing. KHC: Study conceptualization and planning, data collection, and manuscript review. SK: Study conceptualization and planning, data collection, and manuscript review. KKL: Data analysis and interpretation, and manuscript review. DJA: Study conceptualization and planning, and manuscript review. KKCL: Study conceptualization and planning, and manuscript review. SLT: Data interpretation and manuscript review.

Data availability and material

The data supporting this study’s findings is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics approval

202234-11050; REC/07/2022 (OT/MR/3); 32518

Reviewer disclosures

A reviewer of this manuscript has disclosed that they are a member of the Euroqol Group. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no other relevant financial relationships or otherwise to disclose.

Consent to participate

All patients included in this study provided informed consent to participate in the study.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (1.8 MB)Acknowledgement

We thank the research assistants who assisted in primary data collection.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lam CSP. Heart failure in Southeast Asia: facts and numbers. ESC Heart Fail. 2015;2(2):46–49. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.12036.

- MOH. Clinical practice guidelines: management of heart failure 2019. 4th ed. Malaysia: Ministry of Health; 2019.

- Mohamed NF, Yaacob NA, Abdul Rahim AA, et al. Critical factors in quality of life: a qualitative explorations into the experiences of Malaysian with heart failure. Malays J Med Health Sci. 2020;16(2):52–62.

- Sullivan PW, Ghushchyan V. Preference-based EQ-5D index scores for chronic conditions in the United States. Med Decis Making. 2006;26(4):410–420. doi: 10.1177/0272989X06290495.

- Luan L, Hu H, Oldridge N, et al. Psychometric evaluation of the mandarin HeartQoL health-related quality of life questionnaire among patients with ischemic heart disease in China. Value Health Reg Issues. 2022 2022;31:53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.vhri.2022.03.001.

- Spiraki C, Kaitelidou D, Papakonstantinou V, et al. Health-related quality of life measurement in patients admitted with coronary heart disease and heart failure to a cardiology department of a secondary urban hospital in Greece. Hellenic J Cardiol. 2008;49(4):241–247.

- Dunbar SB, Tan X, Lautsch D, et al. Patient-centered outcomes in HFrEF following a worsening heart failure event: a survey analysis. J Card Fail. 2021;27(8):877–887. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2021.05.017.

- McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, et al. 2021 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: developed by the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European society of cardiology (ESC) with the special contribution of the heart failure association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(36):3599–3726. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab368.

- Heidenreich PA, Bozkurt B, Aguilar D, et al. AHA/ACC/HFSA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2022;145(18):e895–e1032.

- Feng Y, Kohlmann T, Janssen M, et al. Psychometric properties of the EQ-5D-5L: a systematic review of the literature. Qual Life Res. 2021;30(3):647–673. doi: 10.1007/s11136-020-02688-y.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence N. NICE health technology evaluations: the manual. UK: NICE; 2022.

- Daccache C, Karam R, Rizk R, et al. Economic evaluation guidelines in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2022;38(1):e35. doi: 10.1017/S0266462322000186.

- MOH. Pharmacoeconomic guidelines for Malaysia. Malaysia: Ministry of Health; 2019.

- Chilbert MR, Rogers KC, Ciriello DN, et al. Inpatient initiation of Sacubitril/Valsartan. Ann Pharmacother. 2021;55(4):480–495. doi: 10.1177/1060028020947446.

- Gandhi M, Thumboo J, Luo N, et al. Do chronic disease patients value generic health states differently from individuals with no chronic disease? A case of a multicultural Asian population. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015;13(1):8. doi: 10.1186/s12955-014-0200-6.

- Pickard AS, Tawk R, Shaw JW. The effect of chronic conditions on stated preferences for health. Eur J Health Econ. 2013;14(4):697–702. doi: 10.1007/s10198-012-0421-8.

- Wang Y, Tan N-C, Tay E-G, et al. Cross-cultural measurement equivalence of the 5-level EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L) in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Singapore. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015;13(1):103. doi: 10.1186/s12955-015-0297-2.

- Lin DY, Cheok TS, Samson AJ, et al. A longitudinal validation of the EQ-5D-5L and EQ-VAS stand-alone component utilising the oxford hip score in the Australian hip arthroplasty population. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2022;6(1):71. doi: 10.1186/s41687-022-00482-7.

- Boczor S, Daubmann A, Eisele M, et al. Quality of life assessment in patients with heart failure: validity of the German version of the generic EQ-5D-5L™. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1464. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7623-2.

- Shafie AA, Vasan Thakumar A, Lim CJ, et al. Psychometric performance assessment of Malay and Malaysian English version of EQ-5D-5L in the Malaysian population. Qual Life Res. 2019;28(1):153–162. doi: 10.1007/s11136-018-2027-9.

- Shafie AA, Chhabra IK, Wong HYJ, et al. Validity of the Malay EQ-5D-3L in the Malaysian transfusion-dependent Thalassemia population. Value Health Reg Issues. 2021;24:47–56. doi: 10.1016/j.vhri.2020.08.003.

- Faridah A, Jamaiyah H, Goh A, et al. The validation of the EQ-5D in Malaysian dialysis patients. Med J of Malays. 2010;65(Suppl A):114–119.

- Rankin J, Rowen D, Howe A, et al. Valuing health-related quality of life in heart failure: a systematic review of methods to derive quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) in trial-based cost–utility analyses [ReviewPaper. Heart Fail Rev. 2019;24(4):549–563. doi: 10.1007/s10741-019-09780-7.

- Di Tanna G, Urbich M, WIrtz H, et al. Health state utilities of patients with heart failure: a systematic literature review. Pharmacoeconomics. 2021;39(2):211–229. doi: 10.1007/s40273-020-00984-6.

- Kuan WC, Sim R, Wong WJ, et al. Economic evaluations of guideline-directed medical therapies for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: a systematic review. Value Health. 2023;S1098-3015(23):02613–0261X.

- Di Tanna GL, Chen S, Bychenkova A, et al. Economic evaluations of pharmacological treatments in heart failure patients: a methodological review with a focus on key model drivers. Pharmacoecon Open. 2020;4(3):397–401. doi: 10.1007/s41669-019-00173-y.

- Varatharajan S, Chen W-S. Reliability and validity of EQ-5D in Malaysian population. Appl Res Qual Life. 2011;7(2):209–221. doi: 10.1007/s11482-011-9156-4.

- Shafie AA, Hassali MA, Liau SY. A cross-sectional validation study of EQ-5D among the Malaysian adult population. Qual Life Res. 2011;20(4):593–600. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9774-6.

- von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ. 2007 2007;335(7624):806–808. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39335.541782.AD.

- Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, et al. The COSMIN checklist for assessing the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties of health status measurement instruments: an international Delphi study. Qual Life Res. 2010;19(4):539–549. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9606-8.

- Krishnan M, Sharmini S. English language use of the Malaysian Tamil diaspora. J Multiling Multicult Dev. 2022. doi: 10.1080/01434632.2021.2020800.

- Swinburn P, Shingler S, Ong S, et al. Assessing the health-related quality of life in patients hospitalised for acute heart failure. Bri J Cardiol. 2013;20(72):6.

- García-Soleto A, Parraza-Diez N, Aizpuru-Barandiaran F, et al. Comparative study of quality of life after hospital-at-home or in-patient admission for acute decompensation of chronic heart failure. WJCD. 2013;03(01):174–181. doi: 10.4236/wjcd.2013.31A025.

- Rutherford C, Costa D, Mercieca-Bebber R, et al. Mode of administration does not cause bias in patient-reported outcome results: a meta-analysis. Qual Life Res. 2016;25(3):559–574. doi: 10.1007/s11136-015-1110-8.

- Gandhi M, Tan RS, Lim SL, et al. Investigating 5-Level EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L) values based on preferences of patients with heart disease. Value Health. 2022;25(3):451–460. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2021.09.010.

- Shafie AA, Vasan Thakumar A, Lim CJ, et al. EQ-5D-5L valuation for the malaysian population. Pharmacoeconomics. 2019;37(5):715–725. doi: 10.1007/s40273-018-0758-7.

- Liu Y, Millsap RE, West SG, et al. Testing measurement invariance in longitudinal data with ordered-categorical measures. Psychol Methods. 2017;22(3):486–506. doi: 10.1037/met0000075.

- Cheung GW, Cooper-Thomas HD, Lau RS, et al. Reporting reliability, convergent and discriminant validity with structural equation modeling: a review and best-practice recommendations. Asia Pac J Manag. 2023;1–39. doi: 10.1007/s10490-023-09871-y.

- Xia Y, Yang Y. CFI, and TLI in structural equation modeling with ordered categorical data: the story they tell depends on the estimation methods. Behav Res Methods. 2018;51(1):409–428. doi: 10.3758/s13428-018-1055-2.

- Berg J, Lindgren P, Mejhert M, et al. Determinants of utility based on the EuroQol five-dimensional questionnaire in patients with chronic heart failure and their change over time: results from the Swedish heart failure registry. Value Health. 2015;18(4):439–448. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2015.02.003.

- Sepehrvand NS, Spertus JA, Dyck JRB, et al. Change of health-related quality of life over time and its association with patient outcomes in patients with heart failure. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(17):e017278. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.017278.

- Göhler A, Geisler BP, Manne JM, et al. Utility estimates for decision–analytic modeling in chronic heart failure—health states based on New York Heart Association classes and number of rehospitalizations. Value Health. 2009;12(1):185–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2008.00425.x.

- Zheng Y, Dou L, Fu Q, et al. Responsiveness and minimal clinically important difference of EQ-5D-5L in patients with coronary heart disease after percutaneous coronary intervention: a longitudinal study. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2023;10:1074969. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2023.1074969.

- Koh D, Abdullah AMK, Wang P, et al. Validation of Brunei’s Malay EQ-5D questionnaire in patients with type 2 diabetes. PLOS ONE. 2016;11(11):e0165555. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165555.

- Senn SS. Statistical issues in drug development. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated; 1997.

- Luo N, Chew LH, Fong KY, et al. Do English and Chinese EQ-5D versions demonstrate measurement equivalence? An exploratory study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1(1):7. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-7.

- Lee CF, Ng R, Luo N, et al. The English and Chinese versions of the five-level EuroQoL group’s five-dimension questionnaire (EQ-5D) were valid and reliable and provided comparable scores in Asian breast cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2012;21(1):201–209. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1512-x.

- Cheung Y-B, Thumboo J, Goh C, et al. The equivalence and difference between the English and Chinese versions of two major, cancer-specific, health-related quality-of-life questionnaires. Cancer. 2004;101(12):2874–2880. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20681.

- Albuquerque de Almeida F, Al MJ, Koymans R, et al. Impact of hospitalisation on health-related quality of life in patients with chronic heart failure. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;18(1):262. doi: 10.1186/s12955-020-01508-8.

- Parizo JT, Goldhaber-Fiebert JD, Salomon JA, et al. Cost-effectiveness of dapagliflozin for treatment of patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. JAMA Cardiol. 2021;6(8):926–935. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2021.1437.

- Stein G, Teng T-HK, Tay WT, et al. Ethnic differences in quality of life and its association with survival in patients with heart failure. Clin Cardiol. 2020;43(9):976–985. doi: 10.1002/clc.23394.

- Griffiths A, Paracha N, Davies A, et al. The cost effectiveness of ivabradine in the treatment of chronic heart failure from the UK National Health Service perspective. Heart. 2014;100(13):1031–1036. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2013-304598.