Abstract

Aims

There are multiple recently approved treatments and a lack of clear standard-of-care therapies for relapsed/refractory (R/R) diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). While total cost of care (TCC) by the number of lines of therapy (LoTs) has been evaluated, more recent cost estimates using real-world data are needed. This analysis assessed real-world TCC of R/R DLBCL therapies by LoT using the IQVIA PharMetrics Plus database (1 January 2015–31 December 2021), in US patients aged ≥18 years treated with rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP) or an R-CHOP–like regimen as first-line therapy.

Methods

Treatment costs and resources in the R/R setting were assessed by LoT. A sensitivity analysis identified any potential confounding of the results caused by the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare utilization and costs. Overall, 310 patients receiving a second- or later-line treatment were included; baseline characteristics were similar across LoTs. Inpatient costs represented the highest percentage of total costs, followed by outpatient and pharmacy costs.

Results

Mean TCC per-patient-per-month generally increased by LoT ($40,604, $48,630, and $59,499 for second-, third- and fourth-line treatments, respectively). Costs were highest for fourth-line treatment for all healthcare resource utilization categories. Sensitivity analysis findings were consistent with the overall analysis, indicating results were not confounded by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Limitations

There was potential misclassification of LoT; claims data were processed through an algorithm, possibly introducing errors. A low number of patients met the inclusion criteria. Patients who switched insurance plans, had insurance terminated, or whose enrollment period met the end of data availability may have had truncated follow-up, potentially resulting in underestimated costs.

Conclusion

Total healthcare costs increased with each additional LoT in the R/R DLBCL setting. Further improvements of first-line treatments that reduce the need for subsequent LoTs would potentially lessen the economic burden of DLBCL.

Introduction

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is an aggressive yet potentially curable malignancy, with around 60% of patients being cured with first-line treatment. The remaining 40% of patients either do not respond, or relapse following an initial response to treatmentCitation1. In DLBCL, the most established first-line treatment is R-CHOP (rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone); building upon this regimen, polatuzumab vedotin in combination with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin and prednisone (Pola-R-CHP) has been recently approved in a number of countries, including in EuropeCitation2 and the United States (US)Citation3. However, in the second line of treatment (LoT) and beyond, there is no universal standard of care for relapsed/refractory (R/R) DLBCL. While the type of treatment given for R/R DLBCL depends on patient eligibility for stem cell transplant (SCT) or chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy with curative intent, many patients are SCT ineligible due to an insufficient response to salvage chemotherapy or the inability to tolerate the treatment-related toxicities associated with SCTCitation4. This lack of a universal standard of care in R/R DLBCL, which is primarily attributed to the limited number of randomized studies in the second-line setting and beyond, has promoted a competitive setting with a number of recently approved novel agents, including CAR-T therapies (e.g. lisocabtagene maraleucelCitation5, axicabtagene ciloleucelCitation6, tisagenlecleucelCitation7) anti-CD19 monoclonal antibodies (e.g. tafasitamabCitation8) bispecific antibodies (e.g. glofitamabCitation9, epcoritamabCitation10) and antibody–drug conjugates (e.g. polatuzumab vedotinCitation11, loncastuximab tesirineCitation12).

Economic analyses have suggested that total annual healthcare costs among patients with DLBCL (excluding CAR-T therapy) are between $142,680 and $267,770, depending on cost inclusions, LoT, and type of treatmentCitation13–15. CAR-T treatments were estimated to have a total discounted lifetime cost of $617,000 using an economic modeling approach in a 2018 report by the Institute for Clinical and Economic ReviewCitation16. However, a recently published analysis of claims dataCitation17 showed that previous studies have likely underestimated the total cost of care (TCC) of these novel therapies in a real-world setting. Indeed, the analysis found that 12% of CAR-T episodes of care (one contact, or a series of contacts with diagnostic or therapy staff, relating to a care plan arising from an assessment or examination) had total costs of $1 millionCitation17. In addition, currently published claims analyses in the R/R DLBCL setting have not included the most recently available real-world data.

Given the rapidly changing treatment landscape in the R/R DLBCL setting, it is important to examine the economic burden and treatment patterns among patients with DLBCL across multiple LoTs to provide more accurate estimates of all-cause costs. Therefore, this study assessed real-world TCC associated with R/R DLBCL therapies, stratified by LoT, using the most recently available data from a robust, nationally representative source of longitudinal healthcare data based on adjudicated medical and pharmacy claims in the US.

Methods

Study design and patients

Healthcare costs and resource use were evaluated using data from the IQVIA PharMetrics Plus commercial claims database, a trusted source of longitudinal data on commercially insured patients in the US regarding their diagnoses, treatments, and adjudicated costs. The study included US-based adult patients who received first-line treatment for DLBCL between 1 January 2015, and 31 December 2021. Patients were required to be at least 18 years of age and have a claim indicating a DLBCL diagnosis (ICD-9-CM 200.7X; ICD-10-CM C83.3X) within the 6 months before the start of inpatient/outpatient first-line treatment with R-CHOP or R-CHOP–like therapy (at least rituximab, cyclophosphamide, and one corticosteroid). Additionally, patients were included only if they had received a second- or later-line treatment of interest (). Patients were excluded if they were not continuously enrolled in a health plan for at least 6 months before receipt of first-line treatment (i.e. the index date). Patients were also excluded if they received R-CHOP or R-CHOP–like therapy as second-line treatment, or received rituximab or lenalidomide monotherapy, had claims for rituximab with a diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis (ICD-9-CM 7.14XX; ICD-10-CM M05.XX), or had claims with diagnoses of other malignant neoplasms of lymphoid, hematopoietic and related tissue within 1 year and prior to 14 days after the index date.

Table 1. Second- and subsequent-line treatments of interest included in this analysis.

LoT after first-line treatment was determined using an algorithm, which was created based on clinician input and advanced LoT whenever a patient began a new regimen, defined as treatment initiation after a gap of ≥60 days from the previous regimen, or the addition or substitution of new agents ≥30 days after initiation of therapy. New agents administered within 30 days prior to CAR-T or SCT therapies did not advance the LoT to ensure the significant pre-treatment costs unique to these two treatments were included. Treatment costs and resource use in the R/R setting were assessed according to LoT (). While the LoT algorithm was not validated, it has been used in a previous analysis of TCC in DLBCL using Truven MarketScan dataCitation18 and is based on algorithms used in other published studiesCitation19,Citation20. TCC was assessed until the end of the patient follow-up period, defined by either patients starting a new regimen (i.e. receipt of a new regimen after a treatment gap of ≥60 days or the addition/substitution of new agents ≥30 days after initiation of therapy), 180 days after the end of treatment, or end of continuous enrollment/data availability, whichever occurred first. In patients with a loss of continuous enrollment in a health plan, outcomes were evaluated for patients only during their continuous enrollment period (i.e. any LoTs started beyond the continuous enrollment period were not included in the analysis).

Figure 1. Study design.

*A LoT is defined by the first 30 days of treatment. A gap of 60 days between treatments advances the LoT, even if the same regimen is received on either side of the gap; †Follow-up refers to the time period during which healthcare costs were recorded, from first administration until the first of the following: patients begin a new regimen (defined by receipt of a new regimen given after a treatment gap of 60 days, or the addition/substitution of new agents ≥30 days after starting initial therapy [adapted from Yang X, et al. 2021Citation27]), or it had been 180 days since they last received treatment, or end of clinical follow-up/date availability.

LoT, line of therapy; R-CHOP, rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone; Rx, start of systemic drug therapy regimen.

![Figure 1. Study design.*A LoT is defined by the first 30 days of treatment. A gap of 60 days between treatments advances the LoT, even if the same regimen is received on either side of the gap; †Follow-up refers to the time period during which healthcare costs were recorded, from first administration until the first of the following: patients begin a new regimen (defined by receipt of a new regimen given after a treatment gap of 60 days, or the addition/substitution of new agents ≥30 days after starting initial therapy [adapted from Yang X, et al. 2021Citation27]), or it had been 180 days since they last received treatment, or end of clinical follow-up/date availability.LoT, line of therapy; R-CHOP, rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone; Rx, start of systemic drug therapy regimen.](/cms/asset/55e6f576-709c-4f57-81ff-810f23787272/ijme_a_2349472_f0001_c.jpg)

Study measurements and outcomes

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics were extracted from the database, and included patient age, sex, geographic region, payment source (commercial versus Medicare), Charlson Comorbidity Index, and the number of chronic conditions (counted using the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Chronic Condition Indicator for ICD-9/10)Citation21.

The primary outcome was all-cause TCC measured by cost per-patient-per-month (PPPM), as this measure helps to control for variation in the follow-up period across the treatments of interest. Total costs per-patient per-line of therapy (PPPL) were also evaluated. Costs were adjusted to 2022 US dollars based on the Consumer Price Index for Health ServicesCitation22.

TCC was measured using the allowed amount reimbursable in the PharMetrics Plus claims. Computed mean costs for TCC included inpatient services, outpatient office visits, outpatient hospital (including emergency department) visits, and pharmacy services. Costs were calculated over the patient follow-up period, and costs for therapies received within 30 days prior to the initiation of CAR-T or SCT were considered pre-treatment for these two therapies instead of the previous LoT. Healthcare resource utilization (HCRU) was defined as the total number and overall proportions of outpatient visits, emergency room visits, and inpatient admissions.

Sensitivity analysis

A sensitivity analysis was performed to identify any potential confounding of the results caused by the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare utilization and costs. To this end, patients were included in the sensitivity analysis if they completed follow-up before 1 April 2020. This date was chosen because the first pandemic-related activity restrictions in the US were issued in the month prior, in states such as New York and CaliforniaCitation23.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations [SD], medians, interquartile ranges [IQR]) were calculated using R softwareCitation24 for continuous data, and percentages were calculated for categorical data.

Data sharing statement

This was a claims database analysis using IQVIA PharMetrics Plus closed claims data obtained under license from IQVIA Inc. The raw data cannot be publicly shared since it was obtained from IQVIA and as per signed agreement between Genentech, Inc. and IQVIA Inc. However, we have provided all relevant data in the manuscript that supports the research objectives and conclusions. We confirm that interested researchers can reach out to IQVIA Inc. to access the data. For further information on data access, please contact: IQVIA Inc.

Results

Patients and therapies received

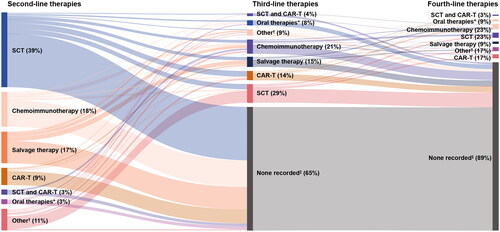

In total, 310 patients who received second-line treatment met the inclusion criteria and were included in the study. Among those, 108 patients continued to third-line treatment and 35 patients initiated fourth-line treatment. Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics of the included patients were similar across LoTs (). The median duration of follow-up from index date of second-line therapy was 20 months (IQR: 13–36 months). Therapies received within each LoT are shown in .

Figure 2. Distribution of R/R DLBCL therapies received across LoTs.

*Included selinexor and ibrutinib. †Included other regimens that were not among the selected treatments of interest; ‡Included patients for whom no treatment was identified during the study period (e.g. due to patient death, change in insurance plan, or lost to follow-up).

CAR-T, chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; LoTs, lines of therapy; R/R, relapsed refractory; SCT, stem cell transplant.

Table 2. Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics according to LoT.

Healthcare costs and HCRU by LoT

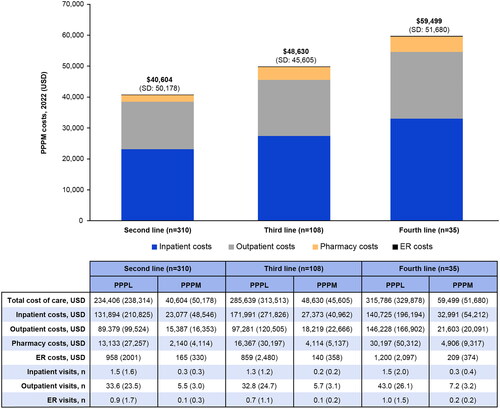

The mean TCC was $40,604 (SD $50,178) PPPM for second-line treatment, $48,630 (SD $45,605) PPPM for third-line treatment, and $59,499 (SD $51,680) PPPM for fourth-line treatment (). Inpatient costs represented the highest percentage of total costs, followed by outpatient and pharmacy costs. Mean PPPM costs generally increased by LoT, with increases appearing to be mostly driven by increasing inpatient and pharmacy claims per subsequent LoT. Costs were highest for fourth-line treatment for all HCRU categories.

Figure 3. Overall PPPM costs by LoT and HCRU category.

Costs shown are means (SD).

ER, emergency room; HCRU, healthcare resource utilization; LoT, line of therapy; PPPL, per-patient-per-line; PPPM, per-patient-per-month; SD, standard deviation; USD, United States dollar.

PPPL costs by highest LoT received are shown in . TCC PPPL was $234,406 (SD $238,314) for second-line treatment, $285,639 (SD $313,513) for third-line treatment (an increase of $51,233), and $315,786 (SD $225,826) for fourth-line treatment (an increase of $81,380). PPPL costs stratified by treatment category are provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Sensitivity analysis

In the sensitivity analysis, 118 patients concluded their follow-up prior to 1 April 2020. Of these, 37 initiated third-line treatment and 13 initiated fourth-line treatment. The mean TCC was $45,080 (SD $41,254) PPPM for second-line treatment, $47,486 (SD $52,128) PPPM for third-line treatment, and $59,412 (SD $36,795) PPPM for fourth-line treatment.

Consistent with the overall analysis, inpatient costs represented the highest percentage of total costs, followed by outpatient and pharmacy costs, and mean PPPM costs generally increased by LoT.

When considering PPPL costs by highest LoT, TCC was $253,107 (SD $260,962) for second-line treatment, $279,539 (SD $395,497) for third-line treatment (an increase of $26,432), and $344,003 (SD $253,075) for fourth-line treatment (an increase of $90,896).

Discussion

There remains a high demand for improved treatments for patients with DLBCL, as approximately 40% of patients with DLBCL relapse or do not respond following first-line treatment, leading to generally poor survival outcomesCitation1,Citation2. While recent approvals of several novel therapiesCitation5,Citation6,Citation12 have provided patients with multiple treatment options, treatment is costly and these costs are increasing over timeCitation13–15,Citation17.

The current analysis assessed real-world costs associated with the treatment of patients with R/R DLBCL according to LoT. The results confirm an increasing healthcare burden with each subsequent LoT in patients with R/R DLBCL, mostly due to increasing inpatient costs and pharmacy claims. There was also a considerable burden to the healthcare system with increasing costs with each subsequent LoT beyond second line, with each subsequent LoT associated with costs of more than $230,000, and PPPL costs totaling more than $315,000 among patients who received a fourth LoT. Of note, PPPL costs stratified by treatment category should be interpreted with caution due to limited patient numbers. Findings of the sensitivity analysis were consistent with the overall analysis, indicating that the results were not confounded by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The current results also provide supportive evidence of increasing costs with each LoT, potentially as a result of increased use of novel approved therapies in more recent years. For example, data from a retrospective, observational study, which analyzed treatment patterns and healthcare costs by LoT among patients with DLBCL treated between January 2011 and May 2017, showed mean healthcare expenditures (adjusted to 30-day period cost and inflated to 2022 US dollars) for first, second, and third LoTs of $26,825, $32,857, and $43,854, respectivelyCitation25. Whereas, similar to the current study, a more recent retrospective claims analysis using data from January 2015 to December 2019 demonstrated that median PPPM costs increased as patients advanced through LoTs, with $33,669 PPPM in the first-line setting, $39,300 in the second-line setting, and $72,224 in the third-line settingCitation26. Another retrospective study, which used post-2015 data from the Optum Clinformatics Data Mart database, showed total costs of $81,669 per-person-per-year, which were higher within the first year following a DLBCL diagnosis, highlighting the substantial clinical and economic burden of treating patients with R/R DLBCLCitation27.

While approved in the second- and third-line R/R DLBCL setting, and despite clear evidence of effectiveness with a manageable safety profileCitation7,Citation28, cost remains a barrier to receiving CAR-T therapy for some eligible patientsCitation29. Thus, optimized use of existing therapies is required to provide patients with R/R DLBCL management options that ensure best possible outcomes despite potential financial constraints on healthcare providers. Given the vast economic burden to healthcare systems of using DLBCL therapies in the second line and beyond, there is a clear need for novel treatments that reduce the need for subsequent LoTs and their associated costs. This can potentially be achieved by reducing the proportion of patients who do not respond to, or experience early relapse after, first-line therapy and/or by avoiding or delaying early relapse. Indeed, patients who remain event free for 2 years have been shown to have similar overall survival to the age- and sex-matched general population at 5 yearsCitation30–32.

The POLARIX study found that the 2-year progression-free survival (PFS) rate was 70.2% with R-CHOP and 76.7% with Pola-R-CHPCitation33. Results of POLARIX ad hoc subgroup analyses among patients with primary refractory disease demonstrated that treatment with Pola-R-CHP reduced the likelihood of primary refractory disease at 24 months compared with R-CHOP treatment (22.7% vs 29.7%, respectively; hazard ratio: 0.75; 95% confidence interval: 0.58–0.99)Citation34. The analysis also showed that primary refractory disease was associated with the use of more intensive second-line therapiesCitation34. Overall, these findings indicated that due to the PFS advantage associated with Pola-R-CHP, the use of subsequent therapies was reduced, with the potential of long-term cost savings.

A strength of the current analysis is that it assessed R/R DLBCL costs stratified by LoT utilizing recent real-world data, which is important given the rapidly changing treatment landscape in this indication. Furthermore, the real-world data approach used in this analysis captured all-cause costs; this has advantages compared with economic modeling, which is limited to pre-specified costs and may not capture the full extent of healthcare expenditures. Some limitations of the study include the potential for misclassification of LoT, as claims data were processed through an algorithm, which may have introduced errors depending on the accuracy of the algorithm used. In addition, the IQVIA PharMetrics Plus Database used in this analysis is predominantly a commercial database; therefore, indirect costs such as work productivity loss or transportation time were excluded, and the results may not be universal to patients with other types of insurance or those lacking insurance. Another limitation was the low number of patients who met the inclusion criteria. Finally, patients who switched insurance plans, had their insurance terminated, or whose enrollment period met the end of data availability may have had truncated follow-up, potentially resulting in underestimated PPPL costs.

Conclusions

In the R/R DLBCL setting, total healthcare costs increased with each additional LoT. Cost estimates by LoT appeared higher than previously reported and may be a result of the increased use of SCT and CAR-T therapies in more recent years. Further improvements of first-line DLBCL treatments that reduce the need for subsequent LoTs would lessen the total economic burden of DLBCL.

Transparency

Declaration of financial interests

JG reports consulting roles with AstraZeneca, Merck & Co., Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Genentech, Inc.; research funding from Merck & Co., Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Genentech, Inc., GlaxoSmithKline; speakers’ bureau from Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi, Kite Pharma. AM, DF, DS, CJ, JL and FH are employees of Genentech, Inc., and receive F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. stocks/stock options. RR is an employee of Genesis Research and receives equity from Genesis Research.

Author contributions

JG, AM, DF, DS, CJ, JL, FH and RR wrote the manuscript and conducted final approvals. JG, AM, DF, DS, CJ, JL, FH and RR conducted study design. AM, DF, DS and RR executed the study. JG, AM, DF, DS and RR analyzed the data.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Previous presentation

Presented as a poster at the 64th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Hematology (10–13 December 2022).

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (12.7 KB)Acknowledgements

Third-party medical writing assistance, under the direction of the authors, was provided by Anna Nagy, BSc, of Ashfield MedComms, an Inizio company, and was funded by F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Sehn LH, Gascoyne RD. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: optimizing outcome in the context of clinical and biologic heterogeneity. Blood. 2015;125(1):22–32. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-05-577189.

- European Medicines Agency. POLIVY® Summary of Product Characteristics 2022 [Accessed August 2023].

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. POLIVY® Prescribing Information 2019 [Accessed December 2022].

- Gisselbrecht C, Van Den Neste E. How I manage patients with relapsed/refractory diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2018;182(5):633–643. doi: 10.1111/bjh.15412.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. BREYANZI® US Prescribing Information 2022 [Accessed July 2023].

- Neelapu SS, Jacobson CA, Ghobadi A, et al. 5-year follow-up supports curative potential of axicabtagene ciloleucel in refractory large B-cell lymphoma (ZUMA-1). Blood. 2023;141(19):2307–2315. doi: 10.1182/blood.2022018893.

- Schuster SJ, Tam CS, Borchmann P, et al. Long-term clinical outcomes of tisagenlecleucel in patients with relapsed or refractory aggressive B-cell lymphomas (JULIET): a multicentre, open-label, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(10):1403–1415. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00375-2.

- Salles G, Duell J, González Barca E, et al. Tafasitamab plus lenalidomide in relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (L-MIND): a multicentre, prospective, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(7):978–988. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30225-4.

- Dickinson MJ, Carlo-Stella C, Morschhauser F, et al. Glofitamab for relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(24):2220–2231. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2206913.

- Thieblemont C, Phillips T, Ghesquieres H, et al. Epcoritamab, a novel, subcutaneous CD3xCD20 bispecific T-cell–engaging antibody, in relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma: dose expansion in a phase I/II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(12):2238–2247. doi: 10.1200/jco.22.01725.

- Morschhauser F, Flinn IW, Advani R, et al. Polatuzumab vedotin or pinatuzumab vedotin plus rituximab in patients with relapsed or refractory non-Hodgkin lymphoma: final results from a phase 2 randomised study (ROMULUS). Lancet Haematol. 2019;6(5):e254–e265. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(19)30026-2.

- Caimi PF, Ai W, Alderuccio JP, et al. Loncastuximab tesirine in relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (LOTIS-2): a multicentre, open-label, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(6):790–800. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00139-X.

- Morrison VA, Bell JA, Hamilton L, et al. Economic burden of patients with diffuse large B-cell and follicular lymphoma treated in the USA. Future Oncol. 2018;14(25):2627–2642. doi: 10.2217/fon-2018-0267.

- Purdum A, Tieu R, Reddy SR, et al. Direct costs associated with relapsed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma therapies. Oncologist. 2019;24(9):1229–1236. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0490.

- Ren J, Asche CV, Shou Y, et al. Economic burden and treatment patterns for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and follicular lymphoma in the USA. J Comp Eff Res. 2019;8(6):393–402. doi: 10.2217/cer-2018-0094.

- Institute for Clinical and Economic Review. Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell Therapy for B-Cell Cancers: effectiveness and Value. 2018. Available at: https://icer.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/ICER_CAR_T_Final_Evidence_Report_032318.pdf. [Accessed: January 19, 2024].

- Sahli B, Eckwright D, Pp G Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-cell (CAR-T) Therapy Real-World Assessment of Total Cost of Care and Clinical Events for the Treatment of Relapsed or Refractory Lymphoma among 15 Million Commercially Insured Members. Presented at the Academy of Managed Care Pharmacists (AMCP) Annual Meeting 2021 [Accessed 02 October, et al. 2023].

- To T, Gu J, Li J, et al. Do patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) receive treatments consistent with national comprehensive cancer network (NCCN) guidelines and what are the total costs of care? Value Health. 2019;22(S1):S94. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2019.04.326.

- Danese MD, Griffiths RI, Gleeson ML, et al. Second-line therapy in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL): treatment patterns and outcomes in older patients receiving outpatient chemotherapy. Leuk Lymphoma. 2017;58(5):1094–1104. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2016.1228924.

- Reyes C, Gauthier G, Shi S, et al. Overall survival and health care costs of medicare patients with previously treated chronic lymphocytic leukemia. JCT. 2018;09(07):576–587. doi: 10.4236/jct.2018.97049.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Chronic Condition Indicator Refined (CCIR) for ICD-10-CM December 2022 [Accessed 22 September 2023].

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers: Medical Care in U.S. City Average. Retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CPIMEDSL. Accessed 09 February 2024].

- Jacobsen GD, Jacobsen KH. Statewide COVID-19 stay-at-home orders and population mobility in the United States. World Med Health Policy. 2020;12(4):347–356. doi: 10.1002/wmh3.350.

- R Core Team. 2023. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/. [Accessed 09 February 2024].

- Tkacz J, Garcia J, Gitlin M, et al. The economic burden to payers of patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma during the treatment period by line of therapy. Leuk Lymphoma. 2020;61(7):1601–1609. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2020.1734592.

- Mutebi A, Jun M, Flores C, et al. Real-world treatment patterns and costs in relapsed and refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the United States. Value Health. 2022;25(7):S394. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2022.04.553.

- Yang X, Laliberté F, Germain G, et al. Real-world characteristics, treatment patterns, health care resource use, and costs of patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the U.S. Oncologist. 2021;26(5):e817–e826. doi: 10.1002/onco.13721.

- Locke FL, Ghobadi A, Jacobson CA, et al. Long-term safety and activity of axicabtagene ciloleucel in refractory large B-cell lymphoma (ZUMA-1): a single-arm, multicentre, phase 1-2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(1):31–42. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30864-7.

- Hoffmann MS, Hunter BD, Cobb PW, et al. Overcoming barriers to referral for chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy in patients with relapsed/refractory diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Transplant Cell Ther. 2023;29(7):440–448. doi: 10.1016/j.jtct.2023.04.003.

- Maurer MJ, Ghesquières H, Jais JP, et al. Event-free survival at 24 months is a robust end point for disease-related outcome in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with immunochemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(10):1066–1073. doi: 10.1200/jco.2013.51.5866.

- Jakobsen LH, Bøgsted M, Brown P, et al. Minimal loss of lifetime for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in remission and event free 24 months after treatment: a Danish population-based study. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(7):778–784. doi: 10.1200/jco.2016.70.0765.

- Maurer MJ, Habermann TM, Shi Q, et al. Progression-free survival at 24 months (PFS24) and subsequent outcome for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) enrolled on randomized clinical trials. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(8):1822–1827. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy203.

- Tilly H, Morschhauser F, Sehn LH, et al. Polatuzumab vedotin in previously untreated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(4):351–363. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2115304.

- Herbaux C, Dietrich S, McMillan A, et al. Cause of death and prognosis of patients (pts) with primary refractory disease, and prognosis of pts reaching PFS24: descriptive analysis of POLARIX. Hematol Oncol. 2023;41(S2):432–433. doi: 10.1002/hon.3164_318.