ABSTRACT:

Aim: This study aimed to obtain estimates for the direct medical charges associated with hospitalizations and emergency department visits of validated SLE cases in a diverse Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) population.

Methods: The Georgians Organized Against Lupus (GOAL) cohort is a population-based cohort of adult SLE patients from metropolitan Atlanta, GA USA, an area having a diverse SLE population. The GOAL cohort aims to study the impact of social determinants of health (SDoH) on outcomes relevant to patients, healthcare providers, and policymakers. For this study, survey data collected during 2011-2012 was linked to the Georgia Hospital Discharge Database (HDD) to capture hospital admissions (HAs) and emergency department visits (EDVs) throughout Georgia from 2012 through 2013. Direct medical charges were summarized by HCU type among all patients, among those with actual visits, and by socio-demographics and healthcare factors.

Results: Among 829 patients (94% women, 78% Black, 64% non-private insurance, 64% not-employed, mean age of 46), 170 (20.5%) and 300 (36.2%) participants had at least one HA and one EDV in 1-year of follow-up, respectively, with 111(13.4%) having both HA and EDV. On average, each patient experienced 0.38 HAs and 0.91 EDVs, with per-patient direct medical charges of $14,968 for HAs & $3,022 for EDVs, and $39,645 per HA & $3,305 per EDV. Patients with higher social vulnerability or more severe disease had higher charges for both HA and EDV (p < 0.01), likely due to the delayed care and neglected health needs leading to more advanced and costly medical treatments. Living below the federal poverty level was associated with higher charges for EDVs (p < 0.001) but with lower charges for HAs (p = 0.036).

Conclusions: This study underscores the economic burden of SLE on vulnerable populations, emphasizing the importance of including socio-economic factors in healthcare planning. Policy efforts should prioritize reducing disparities in access to care and implementing preventive strategies.

Disclaimer

As a service to authors and researchers we are providing this version of an accepted manuscript (AM). Copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proofs will be undertaken on this manuscript before final publication of the Version of Record (VoR). During production and pre-press, errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal relate to these versions also.Introduction

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE, commonly known as “lupus”) is a chronic autoimmune disease that disproportionately strikes ethnic minorities and women, particularly those of reproductive age, with prevalence rates 5-10 times higher in women than men and 3-5 times higher in Black individuals than White1-4. The condition is characterized by widespread inflammation that can lead to tissue damage across various organs, such as the skin, joints, lungs, kidneys, brain, blood vessels, nervous system, and the cardiovascular system1,5. Patients often require management by multiple specialists and medications. This significantly impacts individuals' lives, leading to increased healthcare utilization (HCU) and considerable societal costs6-12.

Several studies in SLE populations have shown that hospitalizations are major causes of healthcare costs13-15, and despite improvements in diagnosis and new treatments, mortality continues to be disproportionately high among SLE patients16. A major limitation of most studies is that the ascertainment and validation of SLE cases depend heavily on administrative/billing codes, which have varying degrees of accuracy, leading to misclassification17,18. Furthermore, previous studies often lacked a population-based approach that included significant representation from vulnerable sociodemographic groups and the full spectrum of insurance types, including those who are under or uninsured11,12,15.

To obtain the estimates for the direct medical charges associated with hospitalization admissions (HAs) and emergency department visits (EDVs) in a diverse SLE population, validated SLE cases from a population-based cohort were matched with the Georgia Hospital Discharge Database (HDD). The results of this study may help to better understand the true economic burden of the SLE population and improve the accuracy of cost-effectiveness estimates and measures in this population.

Methods

Study population

The Georgians Organized Against Lupus (GOAL) cohort encompasses a population-based cohort of adult SLE patients from metropolitan Atlanta, Georgia, who met classification criteria for SLE through rigorous chart review. The overall aim of GOAL is to examine the impact of sociodemographic and healthcare factors on outcomes relevant to patients, healthcare providers, and policymakers. Recruitment and data collection methods, as well as the sociodemographic characteristics of SLE participants, have been previously described19. Briefly, the primary source of SLE enrollees is the Georgia Lupus Registry (GLR), a population-based registry supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in order to better estimate the incidence and prevalence of SLE in Atlanta, an area with a significant African American population, a group known to be at high risk for SLE3.

The GLR was implemented through a partnership between the Georgia Department of Public Health and Emory University; the Georgia Department of Public Health enabled Emory University investigators to review medical records without consent in order to achieve the public health mandate (under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act Privacy Rule, 45 Code of Federal Regulations, parts 160 and 164) to determine the incidence and prevalence of SLE. A case of SLE was deemed as meeting ≥4 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria for the classification of SLE or 3 ACR criteria with a final diagnosis of SLE by the treating Board-certified rheumatologist20. Furthermore, the Georgia Department of Public Health allowed Emory University investigators to contact these individuals and offer them enrollment in the GOAL cohort, which was not allowed in the GLR. Over 70% of lupus patients in the GOAL cohort were derived from the GLR. Subsequent patients with SLE were recruited from a diverse set of clinics and hospitals. Since 2011, GOAL participants have completed annual surveys online, by mail, or in person, covering a broad range of validated sociodemographic and disease measures21. Due to the population-based nature of this cohort, it was not possible to obtain standardized physician assessments. For this study, patient socio-demographics and disease severity data were extracted from the GOAL 2011-2012 annual survey. The GOAL cohort has been approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Emory University and the Georgia Department of Public Health.

Study Measures

Social Determinants of Health

Sociodemographics. We measured a wide range of sociodemographic factors that could potentially impact healthcare utilization and costs (including age, gender, race, education, marital status, employment, and insurance), using self-reported data from the years 2011-2012. Living below the poverty level was calculated with the US 2011 Census Bureau’s 100% poverty threshold using self-reported data on household income and people living in the house22.

Social vulnerability index (SVI). The SVI is a census tract-based metric of 16 social factors or conditions that contribute to a community’s vulnerability to disasters and other stressors (below 150% of the federal poverty level, unemployed, housing cost burden, lacking a high school diploma, no health insurance, aged 65 and older, aged 17 and younger, civilian with a disability, single-parent household, English language proficiency, racial and ethnic minority identification, multi-unit structures, mobile homes, crowding, no vehicle ownership, and group quarters). Each tract receives a separate ranking for each of the four themes, as well as an overall ranking, with scoring ranging from 0-1 and higher index scores indicating greater social vulnerability23,24 The SVI was linked to GOAL participants' home addresses to characterize these various social determinants of health domains (SDoH)25.

Disease Severity

Disease activity. Patients’ perceived symptoms and manifestations of SLE activity in the previous three months were measured with the Systemic Lupus Activity Questionnaire (SLAQ)26, a validated tool that has been used extensively in large epidemiological studies when a physician assessment of SLE activity is not feasible27. The SLAQ includes 24 questions that are scored from 0 to 3 based on symptoms rated as “not a problem”, “mild”, “moderate”, or “severe”. SLAQ scoring ranges from 0-47, with higher scores reflecting greater SLE-related disease activity.

Organ damage. We used the self-administered version of the Brief Index of Lupus Damage (SA-BILD) to measure disease-related damage in SLE. This 28-item survey was validated in our GOAL cohort and other studies28-30. BILD-SA scores range from 0-30, with higher scores indicating greater organ damage.

Healthcare Utilization Data

We linked participants in the GOAL cohort with the HDD to capture all HAs and EDVs throughout the state of Georgia from 2012 through 201331. The HDD provides dates of admission and discharge, the patient’s county of residency, standardized rates for direct charges, and up to 5 ICD-9 codes per admission. Healthcare utilization (HCU) data within the year following patients' completion of their GOAL annual survey was extracted and utilized for analysis, including event type, event dates, length, charge, payor, reasons, and diagnosis.

Data Analysis

Categorical variables were expressed as numbers (percent) and continuous variables as means and standard deviation (SD), describing the SLE patients’ overall characteristics and healthcare utilization status. Direct medical charges of HAs or EDVs within one year of survey completion were summarized by HCU type among all patients and those with ≥1 visit. These visits were expressed as visits per patient, charge per patient, charge per visit, days of stay per visit, and charge per day of stay; direct charge, visits, and stay were then grouped by number of visits (HA or EDV). Results were considered statistically significant for P < 0.05, and all analyses were conducted using SAS software v.9.4 (SAS institute, Cary, NC USA).

Results

Participant Characteristics

We studied 829 GOAL participants who completed the 2011-2012 survey. A description of the study population is summarized in Table 1: the majority were female (94%), Black (78%), not-employed (64%), not currently married (65%), and held non-private health insurance (64%). The mean (SD) for age, disease duration, and education were 46.4 (13.4), 14.2 (2.9), and 13.6 (9.3) years, respectively. Medical insurance coverage distribution included private insurance (35.6%), no insurance (17.5%), Medicare (32.7%), and Medicaid (14.1%) (Table 1). In those with over one year of follow-up, 170 (20.5%) patients had at least one HA and 300 (36.2%) patients had at least one EDV, with 111(13.4%) patients having both HA and EDV.

Direct Healthcare Utilization and Medical Charges

SLE patients experienced on average 0.38 HAs and 0.91 EDVs (Table 2). HA and EDV rates were 381 and 923 per 1000 person-years, respectively. The average charge per patient was $14,968 for HAs and $3,022 for EDVs. The total direct medical charges for the 829 patients were $12.1 million for HAs and $2.47 million for EDVs.

Among patients with at least one HA (n = 170) or EDV (n = 300), the average number of HAs and EDVs per patient was 1.84 and 2.53, with average charges of $72,993 and $8,351, respectively (Table 2). The average charge per HA was $39,645, and per EDV was $3,305; the mean hospital length was 6 days, resulting in an average charge of $6,562 per day of hospital stay.

Direct Medical Charges by Number of Visits per Patient

Table 3 provides statistics for patients with different numbers of HAs or EDVs in one year, including the direct medical charges. 103 (61%) patients had only one HA with a total charge of $4.02 million, which represented 32.4% of the total HA charge ($12.4 million). 8 (4.7%) patients made 5 or more HAs in a year and spent $2.5 million, which represented 20% of the total HA charge.

173 (58%) patients made only one EDV with a total charge of $0.59 million, which represented 23.7% of the charge of EDVs ($2.47 million). 10 (3.3%) patients made 10 or more EDVs in a year and spent $0.68 million, which represented 28% of the total EDV charge. 36 (12%) patients made 5 or more EDVs in a year and spent $1.14 million, representing 46% of the total EDV charge.

Impact of Insurance Type on Healthcare Utilization

Table 4 shows that patients who had a high frequency of HAs were more likely to have Medicare or Medicare/Medicaid coverage, while patients who had a high frequency of EDVs predominantly had Medicaid insurance. Specifically, 9 of the top 16 HA patients had Medicare or Medicare/Medicaid, averaging 6.0 admissions compared to the overall HA mean of 0.38; 9 of the top 16 EDV patients had Medicaid, averaging 15.3 visits compared to the overall EDV mean of 0.91. Notably, however, three of the top five high-frequency EDV patients were either private or had no insurance.

Impact of Socio-demographics and Disease Severity on Direct Medical Charges

Hospitalization

The annual mean charge on HAs was significantly lower for employed patients ($6,122) compared to those off the labor force ($17,657) or unemployed ($21,015), p < 0.001 (Table 5). The mean charge for patients with private insurance was $5,951 per year, significantly less than those without insurance ($13,807), with Medicaid ($16,752), with Medicare ($23,000), or with Medicare/Medicaid ($29,283), p < 0.001; notably, the mean charge for Medicare/Medicaid patients was the highest. On average, patients with Medicare (+/-Medicaid) spent 4-6 times more on HA than those with private insurance. Medicare (+/-Medicaid) patients, comprising 32.5% of the study population, contributed to 54.2% of the total HA charge, while private coverage patients (35.3%) accounted for only 14.1% of the total charge; Medicaid patients were roughly proportional (constituted 14% of patients with 15.7% of the charge)

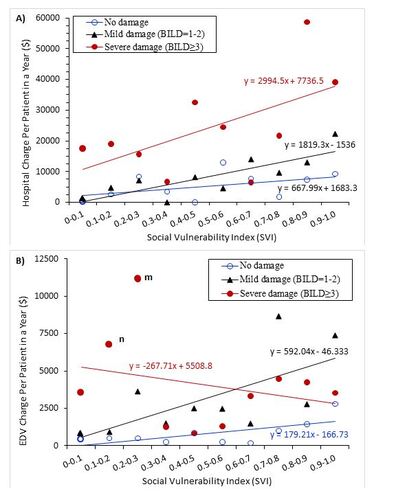

Disease duration, education, and gender had no significant effect on HA charges (Table 5). Notably, younger adults (18-34) and seniors had 2-3 times higher charges than middle-aged adults (p = 0.039). Patients of white race, currently married, or employed had significantly fewer HA charges than their counterparts (p = 0.001, p = 0.007, and p < 0.001, respectively). Peculiarly, those below the federal poverty level had lower HA charges than those above ($13,409 vs. $16,171, p = 0.026), but those with higher social vulnerability incurred higher charges ($24,916, $11,737, and $8,333 for high, medium, and low social vulnerability, respectively, p < 0.001). HA charges were higher among patients with higher disease activity ($20,783, $12,987, and $5,932 for severe, moderate, and mild, respectively, p < 0.001) and more organ damage ($26,857, $9,445, and $5,733 for severe, mild, and no damage, respectively, p < 0.001). The mean charge of HA per patient increased with social vulnerability, increasing by $688, $1,819, and $2,995 per 0.1 increase of social vulnerability for patients with no disease damage (BILD score = 0), mild damage (BILD score = 1-2), and severe damage (BILD score ≥3), respectively (Figure 1A).

Emergency Department Visit

Like HAs, those with middle-age or currently married status had significantly lower EDV charges (p = 0.001 and p = 0.004, respectively). Female and White had 2-3 times higher charges than Male and Black, (p = 0.12, and p = 0.069, respectively), though the charges were not significantly different. Unlike HAs, those characterized with newly disease diagnosis, college or above education, had higher charges for EDVs. Patients off the labor force or unemployed incurred significantly higher charges than those employed ($3,243 and $4,417 vs $1,225, respectively, p < 0.001). In contrast to HAs, living below the poverty level resulted in 3.3 times higher charges than their counterpart (p < 0.001). Patients with Medicaid were charged the most on EDVs ($6,858), about 2-3 times higher than those without insurance or with Medicare, and 4 times higher than those with private insurance; Medicaid coverage patients constituted 14% of the study population but contributed to 31.8% of the total EDV charge. The charge for patients with Medicare (+/-Medicaid) was close to their proportion (constituted 32.5% of patients and spent 32.1% of the charge).

Higher social vulnerability, disease activity, and organ damage were associated with higher EDV charges (p < 0.01). The mean charge of EDVs per patient increased with social vulnerability for patients with no disease damage (BILD score = 0) and mild damage (BILD score = 1-2). Those with severe damage did not show the trend, likely due to the effect of two outliers (Figure 1B).

Discussion

Although many previous studies have focused on SLE healthcare costs, all of them were based on patients from administration claim data32-34; none were population-based with validated diagnoses nor represented a diverse SLE population. Our study, a population-based cohort, assessed HCU and direct medical charges in the years 2012-2013 for 829 SLE patients. By matching cases with the HDD, we found that over a year, 20.5% of patients had at least one HA and 36.2% had at least one EDV; additionally, on average, each of our patients experienced 0.38 HAs and 0.91 EDVs per year.

Our study showed that patients with a disadvantaged status, including those who were young adults, single, had a new diagnosis of SLE, an income below the federal poverty line, or a low level of educational attainment, tended to have higher EDV costs compared to their counterparts, but not on HAs (barring young adults). In addition to the ED being used for higher acuity medical situations, the ED is also often used by those who are uninsured or underinsured. SLE is a chronic condition that drives many into poverty, as seen in this cohort that has 45.1% who are below 100% of the Federal poverty level. Therefore, direct comparisons between HAs and EDVs will be difficult. In addition, the young adult SLE patients, mainly women of reproductive age, together with new SLE diagnoses, had charges that were ∼2-3 times more than other age-group adults. Despite many studies focusing on the overall economic burden of SLE, there is a lack of research on the costs associated with SLE patients who are socially disadvantaged. This gap exists as previous SLE studies mainly relied on administrative claims data from health care plans.

SLE disproportionately affects women and Black patients, with prevalence rates 5-10 times higher in females than males, and 3-5 times higher in Black than White people1,4. Our study found no significant difference in the charge per patient between males and females, and Black patients also did not have higher HA charges. However, charges for Black patients were significantly higher for EDVs than White patients ($3,443 vs. $1,537). Because Black patients (16% on Medicaid, 15% uninsured, and 48% unemployed/disabled) had lower socio-economic status compared to White patients (5% on Medicaid, 2% uninsured, and 22% unemployed/disabled), they may have delayed or had difficult access to specialized care, leading to higher EDVs.

Our study indicated that Medicaid coverage had a notable association with increased EDVs and higher visit charges; Medicare and Medicare/Medicaid coverage, on the other hand, was associated with higher HAs, highlighting distinct healthcare utilization patterns based on insurance types. Patients without insurance had similarly high HA charges compared to those having Medicaid coverage, and similarly high EDV charges compared to those having Medicare or Medicaid coverage, pointing to the role of accessibility and affordability of healthcare.

Patients from communities with high social vulnerability face stressful living conditions. Notably, our study cohort includes a large Black population with a relatively high social vulnerability index. Our study showed that on average, patients with high social vulnerability (3rd tertile) had charges ∼2-3 times more than those with low or medium social vulnerability. In addition, our study showed that patients with severe disease activity or organ damage had much higher charges for both HAs and EDVs, which was consistent with previous findings on cost34,35-36. By considering social vulnerability and disease severity together, the mean charge for HAs per patient was significantly associated with social vulnerability for patients of all disease severities, with the greatest rate of charge increase associated with the most severe disease damage.

Our study has several strengths. Our regional context enables a nuanced exploration of racial disparities in a majority Black SLE cohort, which is lacking in other studies. All cases of SLE were validated as having met classification criteria through chart review instead of relying on administrative coding. Furthermore, as a population-based cohort study, this study fills the knowledge gap in individuals across the entire spectrum of insurance coverage – particularly those who are uninsured – underscoring the necessity for interventions geared towards enhancing the accessibility and affordability of healthcare services to mitigate potential disparities. We also contribute to the literature by further analyzing the social impacts that drive SLE medical costs by incorporating the social vulnerability index scores of patients, which is timely, given the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ recent addition of regular SDoH report requisites for physician reimbursement.

However, there are acknowledged limitations that warrant consideration. Although validated instruments were utilized in the participant questionnaires to the extent possible, physician assessments were lacking due to practical limitations but would have added strength. Despite being a population-based cohort, it cannot claim to have complete ascertainment of cases within the catchment area. Reliance on 2011 data limits its relevance to more recent years. Over this span of time, inflation certainly has increased the overall costs. Although the treatment pathways have not changed fundamentally, there are a few new treatments that have since been approved. Belimumab was the first drug approved for SLE in over 50 years and approved in the U.S. in March 2011. It would have been unlikely to have impacted the outcomes evaluated in this study. However, we acknowledge that belimumab and other medications approved for lupus since 2011, including voclosporin and anifrolumab (another biologic), could be having an impact on patient outcomes on a population level. Further study is needed in this area.

In addition, our use of large databases, even with validated diagnoses, carries the risk of misclassification and inaccuracies from data entry. The study also focuses on direct medical costs and does not account for indirect costs associated with SLE, such as lost productivity, caregiver burden, and other non-medical expenses. These indirect costs can be substantial and categorically contribute to the overall economic burden of the disease. Along the same lines, although we included the social vulnerability index, other social determinants of health that could influence healthcare utilization and costs, such as housing stability, food security, and access to social support, were not fully explored. Future research should consider these factors for a more comprehensive assessment.

Conclusion

SLE-related healthcare utilization in Georgia imposes a significant economic burden, with hospitalizations and EDVs contributing substantially to direct medical costs. Prior studies depended on administrative data to identify cases, which can lead to higher rates of misclassification and a biased selection of patients. This study is the first population-based assessment of direct medical costs in a population with large numbers of Black individuals, who are at some of the highest risk for severe disease and poor outcomes. Socioeconomic factors, including employment status, insurance type, poverty status, and stressful living conditions, emerge as pivotal influencers of these costs, which are often associated with race/ethnicity.

This study underscores the economic burden of SLE on vulnerable populations, emphasizing the importance of including socioeconomic factors in healthcare planning. Policy efforts should prioritize reducing disparities in access to care and implementing preventive strategies.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: DP005119, DP006488, DP00669820

Declaration of financial/other relationships

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Authors’ Contribution

All authors have met ICMJE authorship criteria. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

None stated

Table 1. Description of the study population

Table 2. One-year healthcare utilization and direct medical chargesa for HA and EDV

Table 3. One-year direct medical chargesa by number of HAs or EDVs

Table 4. Insurance coverage typea for patients with high HAs or EDVs

Table 5. Chargesa per patient by socio-demographic factors and disease severity measures among all patients

Figure 1 Association of social vulnerability with the direct medical charges by severity of disease damage (BILD). (A) Hospitalization (HA); (B) Emergency department visit (EDV). In panel (B), points m and n are 2 outliers with severe damage (point n includes a patient with a $73,141 EDV charge; point m includes a patient with a $129,200 EDV charge).

References

- D'Cruz DP, Khamashta MA, Hughes GR. Systemic lupus erythematosus. Lancet. 2007;369:587–596. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04239-2.

- Kaul A, Gordon C, Crow MK, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2016;2:16039. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.39.

- Lim SS, Bayakly AR, Helmick CG, et al. The incidence and prevalence of systemic lupus erythematosus, 2002–2004: The Georgia Lupus Registry. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(2):357–368. doi: 10.1002/art.38239.

- Somers EC, Marder W, Cagnoli P, et al. Population-based incidence and prevalence of systemic lupus erythematosus: the Michigan Lupus Epidemiology and Surveillance program. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(2):369–378. doi: 10.1002/art.38238.

- Maidhof W., Hilas O. Lupus: An overview of the disease and management options. Pharm. Ther. 2012;37:240–249. PMCID:PMC3351863.

- Lau CS, Mak A. The socioeconomic burden of SLE. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2009 Jul;5(7):400-404. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2009.106.

- Elsisi GH, Quintana G, Gil D, Santos P, Fernandez D. Clinical and economic burden of systemic lupus erythematosus in Colombia. J Med Econ. 2024;27(sup1):1-11. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2024.2316536.

- Carter EE, Barr SG, Clarke AE. The global burden of SLE: prevalence, health disparities and socioeconomic impact. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2016 Oct;12(10):605-620. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2016.137.

- Lin DH, Murimi-Worstell IB, Kan H, et al. Health care utilization and costs of systemic lupus erythematosus in the United Sates: a systematic review. Lupus. 2022; 31(7) 773-807. doi: 10.1177/09612033221088209.

- Jiang M, Near AM, Desta B, et al. Disease and economic burden increase with systemic lupus erythematosus severity 1 year before and after diagnosis: a real-world cohort study, United States, 2004-2015. Lupus Sci Med. 2021 Sep;8(1):e000503. doi: 10.1136/lupus-2021-000503.

- Lee J, Lin J, Suter LG, et al. Persistently Frequent Emergency Department Utilization Among Persons with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2019 Nov;71(11):1410-1418. doi: 10.1002/acr.23777.

- Samnaliev M, Barut V, Weir S, et al. Health-care utilization and costs in adults with systemic lupus erythematosus in the United Kingdom: a real-world observational retrospective cohort analysis. Rheumatol Adv Pract. 2021 Sep 16;5(3):rkab071. doi: 10.1093/rap/rkab071.

- Lee J, Dhillon N, Pope J. All-cause hospitalizations in systemic lupus erythematosus from a large Canadian referral centre. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2013 May;52(5):905-909. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kes391.

- Li D, Madhoun HM, Roberts WN Jr, et al. Determining risk factors that increase hospitalizations in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2018 Jul;27(8):1321-1328. doi: 10.1177/0961203318770534.

- Anandarajah AP, Luc M, Ritchlin CT. Hospitalization of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus is a major cause of direct and indirect healthcare costs. Lupus. 2017 Jun;26(7):756-761. doi: 10.1177/0961203316676641.

- Singh RR, Yen EY. SLE mortality remains disproportionately high, despite improvements over the last decade. Lupus. 2018 Sep;27(10):1577-1581. doi: 10.1177/0961203318786436.

- Hanly JG, Thompson K, Skedgel C. Identification of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus in administrative healthcare databases. Lupus. 2014 Nov;23(13):1377-1382. doi: 10.1177/0961203314543917.

- Moores KG, Sathe NA. A systematic review of validated methods for identifying systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) using administrative or claims data. Vaccine. 2013 Dec 30;31 Suppl 10:K62-73. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.06.104.

- Drenkard C, Rask KJ, Easley KA, et al. Primary preventive services in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: study from a population-based sample in Southeast U.S. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2013;43:209-216. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2013.04.003.

- Tan EM, Cohen AS, Fries JF, et al. The 1982 revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1982;25:1271–1277. doi: 10.1002/art.1780251101.

- Lim SS, Drenkard C. Understanding Lupus Disparities Through a Social Determinants of Health Framework: The Georgians Organized Against Lupus Research Cohort. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2020 Nov;46(4):613-621. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2020.07.002.

- US Poverty Thresholds. 2011. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/income-poverty/historical-poverty-thresholds.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Social Vulnerability Index. Accessed April 01, 2024: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/placeandhealth/svi/fact_sheet/fact_sheet.html

- Flanagan BE, Hallisey EJ, Adams E, et al. Measuring Community Vulnerability to Natural and Anthropogenic Hazards: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Social Vulnerability Index. Journal of Environmental Health. 2018;80(10), 34-36. PMCID:PMC7179070.

- Yap A, Laverde R, Thompson A, et al. Social vulnerability index (SVI) and poor postoperative outcomes in children undergoing surgery in California. Am J Surg. 2023 Jan;225(1):122-128. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2022.09.030.

- Yazdany J, Yelin EH, Panopalis P, et al. Validation of the systemic lupus erythematosus activity questionnaire in a large observational cohort. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2008;59(1):136-143. doi: 10.1002/art.23238.

- Karlson EW, Rivest C, Ramsey-Goldman R, et al. Validation of a systemic lupus activity questionnaire (SLAQ) for population studies. Lupus. 2003;12:280–286. doi: 10.1191/0961203303lu332oa.

- Brandt JE, Drenkard C, Kan H, et al. External Validation of the Lupus Impact Tracker in a Southeastern US Longitudinal Cohort with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Arthritis Care and Research. 2017;69(6), 842-848. doi: 10.1002/acr.23009.

- Drenkard C, Yazdany J, Trupin L, et al. Validity of a self-administered version of the Brief Index of Lupus Damage in a predominantly African American systemic lupus erythematosus cohort. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2014;66:888–896. doi: 10.1002/acr.22231.

- Yazdany J, Trupin L, Gansky SA, et al. Brief Index of Lupus Damage: a patient-reported measure of damage in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011;63:1170–1177. doi: 10.1002/acr.20503.

- Georgia Hospital Association. https://www.gha.org/gdds

- Anandarajah AP, Luc M, Ritchlin CT. Hospitalization of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus is a major cause of direct and indirect healthcare costs. Lupus. 2017 Jun;26(7):756-761. doi: 10.1177/0961203316676641.

- Murimi-Worstell IB, Lin DH, Kan H, et al. Healthcare Utilization and Costs of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus by Disease Severity in the United States. J Rheumatol. 2021 Mar;48(3):385-393. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.191187.

- Garris C, Jhingran P, Bass D, et al. Healthcare utilization and cost of systemic lupus erythematosus in a US managed care health plan. J Med Econ. 2013;16(5):667-77. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2013.778270.

- Kan H, Guerin A, Kaminsky MS, et al. A longitudinal analysis of costs associated with change in disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Med Econ. 2013;16(6):793-800. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2013.802241.

- Clarke AE, Yazdany J, Kabadi SM, et al. The economic burden of systemic lupus erythematosus in commercially- and medicaid-insured populations in the United States. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2020 Aug;50(4):759-768. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2020.04.014.