Abstract

This essay argues that the Cultural Cold War is one of the indispensable backgrounds against which the story of modernisms in India must be reconsidered. Using a wealth of unpublished or forgotten documents, it throws light on the ways by which the Cold War shaped the publishing, critical and literary scene in India in the 1950s–1970s, when both blocs were engaged in “pressing the fight” and devising or funding a vast arsenal of “cultural weapons”, such as book programmes, translations and magazines. This background helps to shed light on the “new cultural conversations”, the transnational and translational traffics that were taking place at the time; why and how certain texts and little magazines travelled. By examining in particular the role of two institutions, the ICCF (Indian Committee for Cultural Freedom) and USIS (United States Information Services), as well as pivotal modernist figures such as Nissim Ezekiel, and the editorial stances and choices of English-language journals such as Quest and damn you, the aim is to illuminate some of the “travelling literatures”, the affiliations, rebellions and negotiations which nurtured modernisms in India. “What filters through that curtain is only fit for the international shit-pot” provocatively wrote Adil Jussawalla in 1972, while criticizing the “dreadful dilution” of the literature disseminated by USIS. Many Indian writers also “used” the Cold War (and the worldliness it gave rise to), struggled for the means of political, cultural and literary independence, and defined themselves against the bi-polarization of the world. Bypassing official circuits and dictates, they strove to clear alternative spaces for themselves, to invent their own signature of modernism and define in their own terms the many meanings and forms of “freedom”.

As several critics have started to acknowledge (Monica Popescu in particular), the story of postcolonial literary cultures and literatures – not to mention “world literature” – must also be understood as a Cold War story. This essay argues that the Cultural Cold War is one of the indispensable backgrounds against which the story of modernisms in India must be reconsidered.Footnote1 In earlier work focused on the bilingual English–Marathi poet Arun Kolatkar and the post-independence “little magazine” Bombay fraternity to which he belonged, I defined modernism as a paradigm for emancipation and dissent, and as an offshoot both of the cosmopolitanism of a city like Bombay and of the worldlinessFootnote2 largely produced by the “consumption” of world (including the Indian) literatures in translation. These writers revelled in the multiplicity of traditions, languages, spaces and lineages that make up the worlds they inhabit and the worlds they invent. But if modernisms in India were crafted and reinvented through incessant translational and transnational transactions between English and other Indian or world languages, these transactions are inseparable from the context of the Cold War, at the height of which many modern Indian writers started producing their work.

The importance of reconsidering modernisms in India in the light of the Cold War is obvious if one thinks of Nissim Ezekiel, who is central to modern Indian poetry in English and to Bombay modernisms, but also a crucial figure of the PEN All-India Center and the Indian Committee for Cultural Freedom (henceforth, ICCF) who edited the journal The Indian PEN, and consolidated his “mentorship of generations of young writers” (in the words of Supriya Nair) through channels such as the widely circulated Illustrated Weekly of India, for which he was associate editor. He also became the first editor of the journal Quest, an organ of the ICCF, and book reviews editor of the popular monthly Imprint (that aimed at publishing, as its subtitle claimed, “the best of books every month” in their condensed form), funded by the CIA.Footnote3 Some of the media and spaces through which the critical and literary scenes were shaped at the time, and through which modernisms were crafted, must therefore also be read against the backdrop of the Cold War. That may be the only way, for instance, to contextualize the table of contents of the inaugural 1955 issue of Quest, which includes what have become iconic modernist texts and figures (poems by Dom Moraes and Arun Kolatkar; drawings by M. F. Husain; a review of a film by Akira Kurosawa and a book review of D. H. Lawrence’s posthumous collection of essays Sex, Literature and Censorship), but also a long self-portrait by Ignazio Silone (who contributed to The God that Failed and edited another CCF magazine, the Italian Tempo Presente). The piece is itself introduced by Ezekiel, who traces Silone’s intellectual trajectory from his embrace of the “fanatical orthodoxy” of communism to its rejection. Several full-page advertisements for two other journals sponsored by the Congress for Cultural Freedom in Europe (the London-based Encounter Footnote4 which was subsidized in India, and the Paris-based Preuves) feature as well.

In the course of a recent interview, writer, journalist and human rights activist Salil Tripathi shared his puzzlement.Footnote5 He wondered why Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Miroslav Holub, or Joseph Brodsky were familiar names when he was growing up in Bombay in the early 1970s, while someone of the same age today would not be acquainted with writers such as Asli Erdogan or Liu Xiabo, when these are extremely important writers speaking about the same pressing issues as their Russian or European forebears. Is something not functioning, he wondered? Are the media or free speech organizations such as PEN not doing their job? I would venture that part of the answer lies elsewhere. If these specific writers were part of Salil Tripathi’s intellectual make-up, it is because the transnational literary circulations at the time were also conditioned by a form of embattlement, and by a formidable publishing “machinery”, harnessed by an extremely powerful ideology, that ensured the publication, distribution and canonization of certain writers. The Soviet and Central European names he mentions were all dissident writers whose international dissemination was actively promoted by the “free world”.

This essay discusses the ways by which the Cold War contributed to shape the publishing, critical and literary scene in India in the 1950s up to the 1970s, with a special focus on Bombay. Such a background sheds light on the affiliations and negotiations of certain writers; the transnational and translational traffics that were taking place at the time; the reasons why specific authors were read, published, and translated in India; the editorial stances and the international circuits of journals like Quest, but also of anti-institutional little mags like damn you or Vrishchik; the impact of certain literatures – like Eastern and Central European literatures or the Beats – in India; the importance of foreign cultural centres like the American Cultural Center or the British Council; and the (often oblique or critical) involvement of pivotal modernist figures in India such as Nissim Ezekiel, Dilip Chitre or Agyeya (all members of the ICCF) in that Cultural Cold War.

The aim is obviously not to write a determinist history of the literary scene at the time,Footnote6 but first to examine how Indian literatures and literary cultures were changed by the worldliness, the travelling literatures, the “new cultural conversations” (Quinn Citation2015, 53) and curiosities made possible by the Cold War; second, to reconsider modernisms in India by concentrating on a perspective my earlier work had overlooked, namely the mechanics – politics and economics – of literary transmission and circulation.

While discussing writers like Arun Kolatkar, Adil Jussawalla or Arvind Krishna Mehrotra, who chose to write from the margin, in anti-establishment little mags many of which travelled in unofficial ways, the focus has often been on the chance encounters and clandestine circuits of circulation not dependent on market realities or institutional networks that were at the heart of this literature and of its valuation. Many of the books and journals read by these writers were xeroxed, pirated editions, which were sometimes circulated undercover (“smuggled” is a word used by Arvind Krishna Mehrotra in damn you), or seemed to be chanced upon on the footpaths of the metropolis.Footnote7 Let us recall the oft-quoted story of Arvind Krishna Mehrotra, who as a teenager started publishing damn you: a magazine of the arts from Allahabad after having discovered the existence of Ed Sanders’ New York publication (Fuck you: a magazine of the arts) in an issue of Village Voice sent to his close friend, Amit Rai, by an uncle who was studying on a Fulbright at Columbia University. Hence began his sustained correspondence with people such as Douglas Blazek or Howard McCord, whom he published in his little magazines. Let us also call to mind a moving unpublished fragment from Kolatkar’s diaries, where he writes that a poem is like a “message in a bottle”, which establishes a “strange kind of dialogue” where a writer may take a hundred or a thousand years to find a reader, and the message is meant for anyone who may find it, on any shore, like “the barber in the story … who stumbles upon a secret that he alone knows”.Footnote8 And yet it would be misleading to think that these apparently random discoveries and underground circulations were exclusive of more institutional networks.Footnote9

What’s more, the “signatures of dissent” (Kapur Citation2001) fashioned by some of these little magazines can, to a certain extent, also be read against the Cold War background, and sometimes in reaction to it. A third concern of this essay is therefore to examine the ways by which many Indian writers, critics or artists defined themselves against the Cold War bi-polarization of the world, and often bypassed official circuits, dictates or influences, to clear a space for themselves and follow their own agenda.

Finally, this research aims to intervene in the field of “world literature”, some of whose premises, as Francesca Orsini rightly points out, are questionable; when judgment about circulation becomes judgment about literary value and what does not circulate at “world level” is deemed deficient (Orsini Citation2015). What the Cold War dimension of this history shows is that what often gets to circulate is what is ideologically correct or compatible – literary value only gets the back seat. Literatures that enjoy passport-free travel, that are translated or consecrated at the time are also those which are subsidized by private foundations (like the Ford, the Asia or the Farfield foundations), by governmental agencies and governmental supported organizations (like the Congress for Cultural Freedom), or by state-funded programmes, which all act as “multipliers of the right kind of media” (Whitney Citation2016, 35).

In an interview published posthumously, the modernist Hindi writer Mohan Rakesh acknowledged India had been “a chess board … between the United States’ ideologists and the USSR’s ideologists”, and many intellectuals “were being made pawns in the game” (Rakesh, Singh, and Wajahat Citation1973, 25). Both blocs were indeed engaged in “pressing the fight” (Barnhisel and Turner’s [Citation2010] felicitous expression) and in devising or funding a “vast arsenal of cultural weapons” (Saunders Citation2013, 2), such as books, journals, translations, readers’ digests, festivals, conferences, seminars, exhibitions, radio, film and book programmes, to defend its interests and counter, depending on which side one was on, communist or capitalist challenge.Footnote10 Out of this arsenal, two institutions, the Congress for Cultural Freedom and the United States Information Service (USIS, the overseas service of USIA, the United States Information Agency), seem particularly significant in India. Since the communist-oriented “bloc” is far more documented in the Indian subcontinent,Footnote11 and since the trope of “freedom” with which modernism has often been equatedFootnote12 was turned into a weapon by becoming the central rhetorical catchword enlisted by the United States to rally against communism and counter its own trope of “peace”, this essay focuses on the liberal, US-influenced, anti-communist lineage, and on a journal such as Quest.

The Congress for Cultural Freedom, which was founded in 1950 in West Berlin in order to combat anti-Americanism and counter Soviet influence, was described by its Secretary-General, Nicolas Nabokov, as “an organization for war” (Coleman Citation1989, 29), and in far more official, milder terms as a voluntary association of “free men bound together by their devotion to the cause of freedom” on the opening page of the first issue of Quest in Citation1955. As Margery Sabin has argued, “not everyone remembers how much of an anti-Soviet banner ‘cultural freedom’ had become” at the time, nor how vital it was for the organization to “woo the intellectuals of ‘free’ Asia” (Citation2002, 140–141). India was all the more crucial in that battle for men’s minds, that Nehru’s official non-alignment policy made (in the eyes of many US officials) Indian intellectuals who refused to choose sides particularly vulnerable to communist propaganda.

It is largely due to the CIA’s role in “pumping millions” into the CCF that the CIA has been called, perhaps not exaggeratingly, “America’s ministry of culture” in the 1950s (Saunders Citation2013, 108). One of the Congress’s most influential weapons was the magazines it sponsored or encouraged across the world, such as Quest, Encounter, Preuves, Tempo Presente, Transitions, or Cuadernos. The organization inaugurated a branch in India in 1951, where it held its second international conference, convened in Bombay under the auspices of the magazine Thought, in order for Indian writers and intellectuals to express their “joint resolve to assert, preserve and enhance the freedoms they had attained” – words taken from the “Inaugural Statement” of Agyeya, Secretary of the Congress and editor of Thought (ICCF Proceedings Citation1951, 8). The “sponsor’s appeal” announcing the conference was signed by B. R. Ambedkar, Buddhadeva Bose, B. S. Mardhekar, Jainendra Kumar, Sumitranandan Pant, and Agyeya, among other important writers and modernist luminaries in various Indian languages. Other significant participants in the conference included W. H. Auden, Salvador de Mariaga, Stephen Spender, Denis de Rougemont, Jayaprakash Narayan, Minoo Masani, Raja Rao and K. M. Munshi. Many of the speeches targeted the idea of neutrality. Denis de Rougemont, for instance, weaved his argument around the parable of the lamb (India) unable to choose between the Shepherd (the United States) and the wolf (Communists). Neutralism, he declares, “is the attitude of sheep who secretly wants to be eaten” (ICCF Proceedings, 18–19).

USIS, on the other hand, was founded in 1953, and its mandate covered everything “from the ‘Voice of America’ radio programme to … the dissemination of print materials” (Barnhisel and Turner Citation2010, 12), which were discriminately selected to shed a positive light on the United States. In her self-published memoir, Nuvart Parseghian Mehta, a Cultural Affairs Officer at USIS Bombay in the 1950s, describes the organization as “spreading the good word about American culture” and studying “ways of making the world shrink a bit” (Citation1994, 21).Footnote13 USIS bought foreign rights to many US titles. It had a “Books in Translation Program” scheme, and also ran the United States Information Service libraries charged with the assignment – as an official 1968 USIA manual states clearly – of “building understanding of the United States as a nation, its institutions, culture and ideals … as a necessary basis for the respect, confidence and the support that the US world role today requires” (quoted in Sussman Citation1973, 1). The agency stimulated translation and distribution of US books by financially supporting publishers; guaranteeing purchase of a certain number of copies; subsidizing translations; purchasing paper, but also distributing magazines such as Span or Perspectives USA Footnote14 – itself sponsored by the Ford Foundation and headed by the New Directions founder and modernist figure par excellence, James Laughlin (Citation1952).

The Cold War can be understood both as a form of “synchronization”Footnote15 of literatures across the globe, and conversely, as a form of disjunction, with world literatures and cultures partitioned along antithetical ideologies. Mulk Raj Anand makes a similar diagnosis in a speech called “East–West Dialogue” which he delivered at the Sixth PEN All-India Writers’ Conference held in 1962 in Mysore. If the world is more intimately connected than ever before, he argues, it is also bitterly divided and this division among men and continents was intensified by the Cold War, which is responsible for “arm[ing] literature and mak[ing] it into militant propaganda” (in Ezekiel Citation1962, 114).

On the one hand, the Cold War did contribute to foster a “world literature” in the sense that literature was envisaged as an artefact to globalize, and the Cold War brought writers and literatures into contact and conversation with each other. The Cold War may therefore help to contextualize a text which can be considered as one of the most illuminating manifestoes on literary modernisms in India and on the literary cross-pollination that led to the ebullient creativity of the 1950s and 1960s: Dilip Chitre’s introduction to his influential 1967 Anthology of Marathi Poetry. The poet, who was also a regular contributor of Quest from the mid-1960s onwards, and a member of the executive committee of the ICCF, writes of “the influx of foreign literature on an unprecedented scale”, and of the “paperback revolution” which unleashed a “feverish activity in translation”. It is far from incidental to note that this anthology was sponsored by the International Association for Cultural Freedom (the new name of the CCF after the scandal of CIA funding erupted).

Literature from all over the world began to be competently translated into English, and became immediately available in the form of inexpensive paperbacks. This unleashed a tremendous variety of cross-influences almost of a sudden … A pan-literary context was created … The world shrank greatly during and after the war, joining us vitally with our contemporaries in other countries near and far. (Chitre Citation1967, 5, 24)

The role of these organizations explains why books like Czeslaw Miloscz’s Captive Mind, George Orwell’s Animal Farm, or The God that Failed were widely translated in different Indian languages, and why certain texts found themselves in Quest. Almost all the essays published by non-Indians in the journal from the mid-1950s to the mid-1960s belong to the CCF’s executive committee or to its intellectual constellation. Between 1958 and 1961, to list several well-known names over a short period of time, the following authors appear in its pages: Paul Tabori (“On being Neutral” in the Dec.–Jan. Citation1958 issue), Michael Polanyi (“Tyranny and Freedom” in the Jan.–March Citation1959 issue and in other articles in the late 1950s and Citation1960s), Arthur Koestler (“Literature and Ideology” in the April–June issue of Citation1959), Sydney Hook (“Types of Existentialism” in the July–September issue of Citation1959), Denis de Rougemont (“The Impact of Progress on Freedom” in the Autumn Citation1960 issue), Edward ShilsFootnote16 (a regular contributor of Quest in the 1950s, who serialized his book “The Culture of the Indian Intellectual” in the journal in 1960), and Raymond Aron (“De Gaulle’s Algerian Policy” in the Winter Citation1960–1961 issue), but also reviews of Stephen Spender, Richard Wright, Henry Miller, Boris Pasternak, and Melvin Laski’s books. “In the course of the last half century the whole planet has become involved in one single tumult”, Michael Polanyi, a member of the Congress Executive Committee, argued in his 1959 article. Crediting these transnational circulations of ideas to their intrinsic power (“the ideas for which men fight today have a strength of their own” [9]), he also exemplifies the propagandist’s mission: to make us believe in the autonomy of ideas that are in fact the object of covert patronage.

The worldliness fostered by the Cold War was also, at least in part, an “Americanness” that helps to contextualize the American affiliations of a literary and artistic Bombay subculture (King Citation1985; Zecchini Citation2014).Footnote17 Many writers or intellectuals who started writing or were brought up in Bombay in the 1950s or 1960s, and even the early 1970s (Amit Chaudhuri [Citation2013, 203] talks of the “comic book-idyll of 1950s America” in the Bombay where he grew up), point to the pervasiveness of American popular culture in their youth, such as comics, cartoon strips, gangster films, or rock & roll, and to the fact that post-Independence Bombay seemed to have so much of America in it. Arjun Appadurai, for instance, remembers that the experience of modernity was bound up with the image and aura of the United States:

I saw and smelled modernity reading Life and American college catalogs at the United States Information Service Library, seeing B-grade films (and some A-grade ones) from Hollywood at the Eros theatre. I begged my brother at Stanford (in the early 60s) to bring me back blue jeans and smelled America in his Right Guard when he returned. I gradually lost the England that I had previously imbibed in my Victorian schoolbooks … Such are the little defeats that explain how England lost the Empire in postcolonial Bombay. (Appadurai Citation1996, 1–2)

This Americanness must also be reexamined as a product of the Cold War. The impact of rock & roll and the blues on a poet like Kolatkar, for instance, is directly connected to the hugely popular US-government funded Voice of America radio programme, transmitted through Radio Ceylon, at a time when western music was banned from the state-run broadcasting network. In Taj Mahal Foxtrot, Naresh Fernandes has resurrected the story of India’s – and especially Bombay’s – “jazz age”:

the stretch between the railway terminus and Marine Drive was so lively with jazz in the late 1950s that many Indian musicians insisted it was exactly like the club-lined 52nd street in New York that they read about in Downbeat. (Citation2012, 147)

“No capital city lacks its U.S.I.S. or Palace of Culture” writes David McCutchion somewhat sarcastically in a 1960 issue of Quest. Footnote20 The USIS library, or American cultural centre as it was called, was a vital cultural landmark in Bombay and a literary treasure-trove for many budding writers. Arvind Krishna Mehrotra remembers stealing books from both the USIS and the British Council libraries when he was a student in Bombay in the late 1960s (Citation2002). “Where else could we find certain poets, certain novelists, certain critics, certain films?” acknowledged Adil Jussawalla in a recent interview. He also recalled America’s PL 480 Program, which brought affordable editions of American books to India: “I owe PL 480 the pleasure of reading the best American playwrights in a priceless edition. And let’s not forget the cheap Soviet editions of important writers, easily available on some of Bombay’s pavements and in some of its shops. They were invaluable” (Nerlekar and Zecchini Citation2017b, 228–229). In a delightful unpublished fragment on the 1989 World Poetry Festival in Bhopal, Kolatkar describes how he resurrects various poets and exhumes their collections from biscuit boxes where they had languished for years, also humorously acknowledging his debt to USIS: “guiltily … I look at the bald eagle / at the usis sticker … on the selected poems of Theodore Roethke the book is 30 years overdue”. And he continues: “I select the poets I soon expect to meet in person and stack them up build myself a modest tower of Babel … Using the collected poems of allen ginsberg as foundation for sheer solidity the harper and row edition is unmatched with its bloodred dust jacket / and top up with holub amichai and popa.”

Significantly, Mehrotra’s first line of the first letter he sent on 16 October 1966 to the American writer and small press founder Howard McCord mentions USIS as the place to visit if you are an aspiring Indian writer with an editorial project in mind (and no cash!):

It was six months ago that I went to the USIS, Delhi and met R. R. Brooks who is in charge of its cultural side and asked him for funds to help me take out an anthology of Indian students writing in English.Footnote21

As Mulk Raj Anand made clear, however, the synchronization or interconnection of nations, cultures and literatures across the world is only one dimension of the Cold War, which also divided nations along ideological lines, and internally fractured national literary cultures. Although several countries in Asia and Africa, he argues, have tried to remain outside its orbit, the literature of these countries has been divided on the basis of doctrines which “have no relevance to resurgent peoples” (in Ezekiel Citation1962, 114).

The Cold War undeniably sharpened the debate between the “politics of art” and its autonomy. “Not until the Cold War was this idea of literary autonomy itself wielded by a national institution like the CIA, via the Congress for Cultural Freedom, for ideological ends”, argues Justin Quinn (Citation2015, 36). The division between what has come to be known in the West as “abstract expressionism” or “abstraction” – articulated in Clément Greenberg’s (Citation1961) early essay “Avant-garde and Kitsch” published in Partisan Review in 1939, where he defines the avant-garde as art in which it is difficult to inject effective propaganda because it turns away from subject matter and from the masses – versus social realism also raged in India. It took an indigenous form with the prayogvaad (experimentalism in Hindi) or “literature for literature’s sake” versus pragativaad (progressivism) or “literature for life’s sake”, which also gets mapped onto the individualist/liberal versus collectivist fracture, and at times intersects with the opposition between government- or institution-sponsored art and literature versus one that refuses to be straitjacketed by the state or by ideology.Footnote23

But if these issues were hotly debated in Indian journals, anthologies and manifestoes in English, Hindi, Urdu, Marathi, Bengali and other Indian languages at the time, many Indian writers struggled to liberate themselves from such sterile binarisms. That was actually, as Mohan Rakesh explains, one of the raisons d’être of “nai kahani”, which he defines as a literary movement of “dissimilar individuals” that was condemned by die-hard progressives on the one hand, and by the proponents of the “Art for Art school” on the other, because it was not alienated from everyday life, but did not consider literature as the “elaboration of an idea” (Rakesh, Singh, and Wajahat Citation1973, 16–18).

Between American Shadow over India (a book published by the Bombay-based communist “People’s Publishing House” in Citation1952) and Moscow’s Hand in India (a book brought out by the anti-communist Swiss-Eastern Institute in Bern in Citation1966), Indian writers and intellectuals were far from mere pawns in the game. Although some of the protagonists of this story would perhaps not embrace the poet Ranjit Hoskote’s enthusiasm (he contends the Cold War was only one more opportunity in a “festival of opportunities”),Footnote24 they definitely cleared a space for themselves within a space that was originally defined for other means.

Hence, despite Quest’s anti-communist ideological lineage,Footnote25 Margery Sabin is right to claim that what attracted writers to Quest was a “hope that they could use rather than be used by their own sponsors” (Citation2002, 143). Nissim Ezekiel’s obsession, which is manifest in many of his early editorials, is for Quest to foster an independent critical culture; to cultivate criticism and freedom of tone; to create the conditions in which freedom (freedom to argue, to question, to probe, to doubt, to disagree, to criticize, and even to attack) can thrive in India; and cultural freedom or independence can realize political freedom. It is this culture that Quest aimed at revitalizing in the critical and the creative fields, in order to provoke or sustain intellectual debate, and displace, in the words of Ezekiel, the “coexistence of ideologies” with a “ferment of ideas” (Quest Citation1957, 9).

Another editorial, which is also prophetic of the Emergency, gives the tone of his “quest”:

What exactly do we mean when we call a society free? … The question raised at the outset cannot be answered merely by asserting that the communist society is the perfect antithesis of the free society … A non-communist society such as the Indian does not automatically qualify for the label free. In fact … there is a constant need to explore the conditions in which it exists. We must probe, doubt, question, question, question. As soon as freedom is taken for granted, it is already diminished. Before freedom is destroyed a state of mind must be popular to which freedom does not matter … There may be more censorship in India during the years to come and it will not be an accident. (Quest Citation1956, 3–4)

Likewise, despite CCF patronage and funding, the 1951 inaugural ICCF conference in Bombay bears witness to the fact that many Indian writers and intellectuals refused to submit to outside pressure or to align themselves along ideological lines. Several Indian participants seemed far more interested in discussing cultural issues than communism per se, openly voicing their disagreements with some CCF members, and even their anti-Americanism.Footnote26 Participants such as Buddhadeva Bose, Jayaprakash Narayan or Jyoti Swarup Saxena, in particular, point to the fallacy of having to choose between the “shepherds” and the “lambs”,Footnote27 and to the dangers that freedom falls prey to “under the constant sniping of the totalitarians of the Right and the no less dangerous totalitarians of the Left”, when writers are split into clear-cut camps and the freedom of the artist is relinquished in order to “take up arms against the forces that threaten to destroy it today” (words of J. S. Saxena, ICCF Proceedings 1953, 163 and 158). “Refusing to be terrified”, Buddhadeva Bose writes, “we in India can in any event try to build our lives in our own quiet way, instead of modelling ourselves on any of the great world powers, who are now the hope and the terror of other nations” (ICCF Proceedings Citation1951, 162).

A member of the ICCF and regular contributor of Quest, J. S. Saxena gives this struggle for freedom a poignant, enraged and often self-lacerating tone, in an extraordinary article entitled “The Coffee-Brown Boy Looks at the Black Boy”, published in the April–June Citation1970 issue of the journal, which weaves together a dizzying array of references to Frantz Fanon, W. E. B, Du Bois, James Baldwin, Muddy Watters, Leon Bloy, Herbert Marcuse, Iris Murdoch, and Ornette Coleman, among other writers and artists. “How do we stop being somebody else’s image?” he asks, while rejecting the “brown-boy’s” compulsion to catch up with Jacobin France, with Victorian England, with Roosevelt’s America or with Stalinist Russia.

Two centuries ago, as Frantz Fanon puts it, a former colony of Europe and, if I might add, a rather backward Euro-Asian country decided to catch up with what was known as the West. They succeeded so well that the United States and its mirror-image, the Soviet Union, have become the most frightening monsters Man has ever known. (70).

This “logic of refusal” signals in part the passage from the height of the Cold War in the 1950s and early 1960s, to the late 1960s and 1970s, which is also the internationalization of Counterculture; and the move from an officially endorsed or government-sponsored culture, to subcultures which not only valorized unofficial art and “cultural outlaws”,Footnote28 but tried to recover the oppositional spirit of the avant-garde little magazine before its institutionalization by Cold War cultural politics. Both Elisabeth Holt (Citation2013) and Greg Barnhisel (Citation2015) have convincingly argued that the CCF sought to inherit the legacy of the little magazine, but without its anti-bourgeois ethos and material vulnerability. Encounter is the perfect illustration of the progression of modernism and of its privileged vehicle, the magazine, “from the fringes to the center” (Barnhisel Citation2015, 160).

In the Indian case, however, this transition only partially coincides with the passage from one type of journal (such as Nissim Ezekiel's visually conventional Quest) to another (for instance, Mehrotra’s handcrafted, untutored and anti-establishment damn you). When Mehrotra set out to “oil and set the mimeomachine like a machinegun” (damn you) from Allahabad, he certainly had in mind both the radical American little mags of the time, and the early twentieth-century modernist and imagist magazines,Footnote29 calling for the same provocative assault on social, cultural, and literary conventions that Blast (advertised in The Egoist) represented: “my ears are still buzzing … with the words of a full-page advertisement published in The Egoist of 1 April 1914” (Citation2012, 150). Yet, as suggested earlier, countless articles of the 1950s and 1960s in Quest opposed state patronage in the arts and literature, and Ezekiel, who was wary of bureaucracies and academies, tirelessly strove to create a critical platform that he intended to be independent, pluralist and non-conformist – all qualities which he associated with liberalism.Footnote30 What’s more, many writers found themselves in both types of magazine – emblematically, Ginsberg was also published in Quest, and the last issue of Ezekiel’s Poetry India (April–June 1967) included advertisements for Mehrotra’s damn you and for Carl Weissner’s “avant-garde little mag” Klactoveedsedsteen, calling for the submissions of Indian poets.Footnote31

Douglas Blazek, the American poet, editor and Mimeo Revolution founder who regularly corresponded with Mehrotra, defines the underground ethos and dissenting spirit of many little mags of the 1960s in a letter to the Indian poet in 1967:

writers or magazines which are small in circulation & publish material that is not generally acceptable to the masses or even to the fairly advanced literary follower simply because it is out of tune w/what is taught to be fashionable or correct or good or acceptable.

I have discussed elsewhere the “conspirational” ethos of these little magazines (Zecchini Citation2017), which were anti-commercial, anti-academic, anti-elitist ventures, at odds with the cultural, institutional and publishing mainstream. Suffice it to say here, that writers, editors and artists such as Adil Jussawalla and Arvind Krishna Mehrotra, Arun Kolatkar, Ashok Shahane, and Gulammohammed Sheikh, created small presses and short-lived, cyclostyled or mimeographed little magazines where they cleared a space for themselves collectively, and often transnationally. Putting their own financial and creative resources, their contacts and networks into these publishing ventures, they bypassed middlemen and gatekeepers of literature, and became the editors, critics, designers, and promoters of each other’s work. “We have been the only means by which poetry has been kept alive while the big publishers slept … Welcome to the conspiracy” (Jussawalla Citation1978, 6). Vrishchik (which literally means “scorpion” and like other anti-establishment magazines was meant to “sting”), started from Baroda by the two prominent visual artists, Gulammohammed Sheikh and Bhupen Khakhar (Citation1969–1973), spearheaded the struggle against the national academy of arts (the Lalit Kala Akademi). The institution which had been set up by the government of India represented the Indian art establishment per se and was defined by Vrishchik editors as a hotbed of mediocrity and a “complacent body wasting public money in the name of art” (1971), which failed to represent the youngest, most creative and progressive artists. The magazine also aligned itself with the international Counterculture of the time and the anti-Vietnam movement. The April 1970 issue, for instance, reproduced from the US journal The Progressive a selection of letters sent by an American GI in Vietnam with the following editorial:

These letters … tell the bitterest stories ever told. It mocks at the fake capsules of humanity presented to us by the glamorous propaganda of the Big Nations. That in spite of mass demonstrations of the young and appeals of the intelligentsia all over the world, the mass murders in the villages of Vietnam continue. Perhaps it is high time for the young nations to rise, and challenge the supremacy of great powers, at whatever cost. (Vrishchik April 1970, n.p.)Footnote33

However, I would argue that these alternative voices, spaces and affiliations are also part of the new conversations and affiliations generated – though by reaction – by the Cold War. Justin Quinn highlights the unquenchable thirst for unofficial art from the 1960s onwards, on all sides of the Iron Curtain, and the attraction for expressions disdained by “grey eminences of the American intelligence”:

The CIA might well have dropped Russian translations of Eliot’s Four Quartets into the USSR, but the East, like the rest of Europe first and foremost wanted to know about jazz, rock and roll, the Beats and other expressions of the subculture that the grey eminences of the American intelligence disdained. (Quinn Citation2015, 53)

It is tragic … that the young … do not see that during the passage of any art from the colonizer’s country to them, a dreadful dilution takes place. Sometimes it takes place at the source. Castration, then, is the better word for it. (Art as presented by various international agencies like the USIS and the British Council, is simply art with its balls removed.)

Of course, the curtain is also, in Jussawalla’s article, the “purdah” of English – both the language into which world literatures make it to India and the “very correct” idiom used by most Indians, from which there is no escape but into “the Little Englands and Little Americas” his students and their parents have built around themselves. Art is not just selected, but trivialized or, indeed, castrated: the violence and the morally painful, the inventive and the demotic, the culturally and politically radical are kept at bay:Footnote36 “what filters through that curtain is only fit for nothing but the international shit-pot”. In some ways, Jussawalla’s frustration echoes Saxena’s, whose text revolves around the imperative to resist sterile mimetism, to discard abstractions in order to confront a brutal reality (which he equates to the “sheer, concrete, thinginess of things”) and to reclaim feelings, forms and words of rage and agony that have not first been framed, thought or voiced by others, and in the process tamed and trivialized: “What is an Indian? … Imprisoned in other people’s metaphors, he cannot even experience his prison … Put [human beings] in a frame, sometime they will break out of it and begin to live”.

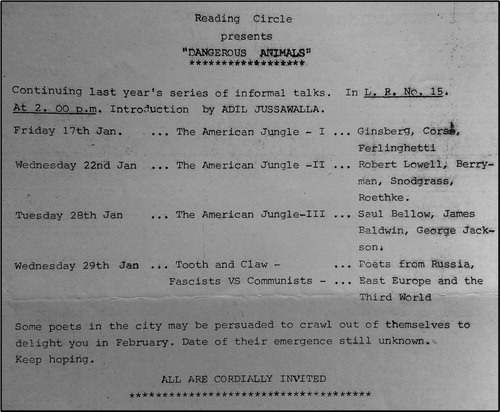

It is because of that dreadful dilution that in the same text Jussawalla calls for the “living acid” of the contemporary Indian writer in English and his translating counterpart to eat the curtain away. The “Dangerous Animals” series of readings, which he organized at St. Xaviers’ College in the early 1970s, must also be understood in that light. The sessions entitled “The American Jungle I” and “The American Jungle II” included names such as Ginsberg, Corso, Ferlinghetti, Robert Lowell, Berryman, Snodgrass, and Roethke. The invitations and flyers used to publicize the readings reveal the highly embattled context of the literary and critical scene at the time, with several sessions entitled “Tooth & Claw: Fascists vs. Communists”, etc. Jussawalla’s aim was also to persuade Indian poets “to crawl out of themselves” and read their own poetry (). Mehrotra, whose venue is announced in October 1974 on one of the flyers, is introduced as a “dangerous animal from Allahabad”. No doubt, in Jussawalla’s eyes, could the “acid” of Mehrotra’s art, “having wrestled with the curtain, having torn holes in it” (“Boys and Girls in Purdah”) show the way out.

Figure 1. Flyer for the “Dangerous Animals” series of readings organized by Adil Jussawalla at St. Xaviers' College (1974).

It is also because of the diagnosed “castration” – and not only because of the anti-communism in the air – that many of the same Indian writers acknowledge the lasting importance of Central and East European poets, whose urgency they admired, and who were channeled in Asia thanks to Al Alvarez and his Penguin Modern European series. In many respects, poets like Miloscz, Brodsky, Holub and Herbert were, as Quinn explains, “the most important poets of the era in the Anglophone world”.Footnote37 In an article published in another student periodical (The Allahabad University Magazine), Mehrotra writes that the difference between Philip Larkin and the “sad corpse” of much of “insular” contemporary British poetry and the “startling worlds” of Eastern European poets like Holub of Czechoslovakia, Herbert of Poland, and Popa of Yugoslavia is that of “snow-laden leafless tree and a blade of grass”. Of course, Mehrotra is also championing his own craft, as a maker of poems that should not be “artfully constructed as hives” but should “flow like forest-fire” (Citation1970, 5).

It is in such a context that several Indian writers’ affiliation with the Beats must be understood. Ashok Shahane, Arvind Krishna Mehrotra and Arun Kolatkar seemed to recognize their own anti-establishment iconoclasm (their appetite for an art or a literature with its balls “re-grafted”, if I may be allowed the expression) in the Beats, but also their fatigue with political, cultural or literary fronts, with ideological grids or compartmentalizations,Footnote38 and their desire for an alternative. Ginsberg notoriously dismissed both capitalists and communists, and was considered undesirable by both blocs. “And the communists have nothing to offer but fat cheeks and eyeglasses and lying policemen / and the capitalists proffer Napalm and money in green suitcases to the Naked”, he wrote in his poem “Kral Majales” (Citation1968, 89).

If the anti-elitist, anti-academic spaces which flourished outside institutional support of many little magazines of the 1960s that were all at once marginal or eccentric spaces and worldly,Footnote39 effectively created what Eric Bulson has called a “decentered literary universe” (Citation2012), it is in more senses than one. Of course, these magazines circulated across the world from periphery to periphery, subculture to subculture. They also dismissed both “blocs”, or “capitals of the skyscraping earth” (to use Mehrotra’s expression in damn you 6), challenging the stranglehold of big powers, and fashioning a signature that was dissenting or decentered in myriad ways: “Nothing was sacred; the gods – whether of religion, politics, commerce, or indeed poetry – were there to be lampooned”, wrote Mehrotra as he recalled the spirit of anarchy and refusal that presided over his little magazines in the 1960s (Citation2010, 277).

“A hundred Indo-Anglian years, which is to say an eternity, should have separated Ezekiel (b. 1924) and Kolatkar (b. 1931). Tragically for us they belong to the same generation”, he also acknowledged in a razor-sharp essay, “The Emperor has no Clothes”, initially published in 1980 (Citation2012, 155). Ezekiel certainly embodied a form of establishment at the time, at least as an instance of consecration,Footnote40 and was therefore one of the inevitable casualties of Mehrotra’s “blasts”. In his correspondence with Howard McCord, he makes a sharp distinction between the elder poet and himself, between his little mags which are “mimeo, small in circulation and publish unheard of writers” and Ezekiel’s magazines like Quest or Poetry India which are on the side of the establishment and “have to be dynamited if we are to be heard”. These two magazines, he writes, “are reeking with the bourgeois, where the avant-garde is given a kick in the guts” (16 October 1966).

In a text enclosed in another letter to McCord, he describes this establishment as “consisting of phony writers, many Indians writing in English, middle-aged intellects in terrylene; in short a dozen bastards without teeth or claws”, and admonishes his readers: “if you know you have genius in the raw; if you know you are good enuf, yet not bad enough for those weeklies and quarterlies: then send on your stuff to us … yes, be bitter, bite, scratch, bark” (26 December 1966). Remember the “teeth and claws” of Jussawalla’s “Dangerous Animals” readings! The poet Lawrence Bantleman, reviewing both Mehrotra’s damn you (Citation1965–1968) and ezra (Citation1967–1971), and Ezekiel’s Quest in a December 1966 issue of The Century, makes a similar kind of opposition: “Anybody cheesed-off the literary establishment in India will welcome these two magazines, if only for the revolt of these students. The Illustrated–Ezekiel–Lal axis if they are not already awake, ought to beware” (15). He defines Quest as the “peak of pretension in India” and summons the journal to include “real, live, biting things … raw, honest stuff”. The poems Ezekiel publishes, he adds, “need a stick in their backside” and its stories “a bit of pornography” (16).Footnote41 It is however revealing to note that despite the stark (and strategic) contrast between the two magazines put forward by Mehrotra and Bantleman, the same metaphors find themselves under Dilip Chitre’s pen in an article published in Quest, and in reference to another CCF-sponsored journal. In his article “Rajat Neogy’s Transition” (April–June 1969), Chitre praises Neogy’s editorial work for his championing of irreverence (as “antidote to comatose academism and servile decay”) and argues no intellectual magazine can survive “without encouraging biting, tearing apart and other types of intellectual savagery for savagery’s sake”.

Mehrotra’s little magazines did boast of irreverence, absolute freedom, and brash confidence. ezra 1 proclaims: “Preference will be given to poets who have not yet been published before … the mag might smack of ‘beatness’. you are wrong. it is gently avant-garde … four-letter words and a one-letter word will be treated equally … you like it or lump it”. And all issues of damn you open on “statements” which function like manifestoes, and express the ambivalence of such documents, which are both anti-programmatic and furiously assertive. Damn you is not the mouthpiece of a writer or a literary school, a country, a party or an ideology, not even an epoch:

not the organ of a hungry generation, a clan of anti-poets, or a writer’s workshop. not the public child of a Bombay professor. we are illiterates. unaware of ists/isms … we are men, breathing. and we breathe for ourselves. not for the ‘age we live in’. (statement of damn you 6)

It provocatively flaunts its refusal to be pigeonholed into neat national or ideological categories, derides and predictable alignments, resists political and cultural recuperation: “the financial benefits (what a hope.) are not meant for ourselves. poor boy’s fund. viet-nam. (before you pigeon-hole us, we didn’t specify which side.)” (statement of damn you 1). It doesn’t pledge it’s allegiance to the United States, to the United Kingdom, nor even to the Beats: “there is more than wishing to see the earth thru someone’s hymen” (statement of damn you 4), and as the last lines of his statement in damn you 6 illustrate, “fuque(s) politiques”, “collapsible governments” and “capitals” of the world:

dig in. make zigzag trenches. fire back. oil and set the mimeomachine like a machinegun … fuque politiques. DY has nothing to do with collapsible governements. ken geering the editor of breakthru thinks we are yankee oriented, a yankee, eric oatman who edits the manhattan review writes “the name is too damn british”. and so, we like to keep them guessing, and leave the capitals of the skyscraping earth to decide amongst themselves.

Acknowledgments

Preliminary versions were presented at several conferences, including at the “Postcolonial Print Cultures” conferences organized in January 2018 at Newcastle University and at the SOAS in London in January 2019. I would like to thank Adil Jussawalla for making available many of the unpublished or forgotten documents on which this article is based.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 This essay is born from one of the unexpected directions of an AHRC-funded project on writers’ organizations – especially PEN International – and free expression. It aims to document how writers and writers’ organizations have influenced the right to free speech, to examine the challenges they face in defending it and to explore the internationalism that organizations like PEN constitute. Because the Indian branch of PEN International was part of the same intellectual constellation as the Indian branch of the Congress for Cultural Freedom, indirectly funded by the CIA, the Cultural Cold War emerged as a crucial dimension of this research.

2 Edward Said defined worldliness as the quality of writers and literatures that are part of the social and secular world in which they emerge, and as the opposite of separatism and exclusivism. Wordliness, he argued, is the restoration to such works of “their place in the global setting” that is not accomplished by an appreciation of “some tiny, defensively constituted corner of the world, but of the large, many windowed-house of human culture as a whole” (Citation2000, 382). This essay aims at restoring the wordliness of these literatures by showing how they are connected to political and historical circumstances, and to the whole world of other literatures, but also inseparable from the experience, the expression and the defense of plurality. Worldliness can also be understood as a defiant gesture on the part of many of these writers to reclaim an India that includes what is non-Indian, and to put forward, through translation and a “cut-and-paste” collation of the world and world literatures (see Zecchini Citation2019), an idea of interconnectedness where, to quote Ezra Pound (himself cited by Mehrotra), provincialism is the enemy (Mehrotra Citation2012, 162).

3 See, in particular, Knightley (Citation1997).

4 The magazine initially aimed at promoting “East–West encounter”, and at winning an Asian readership.

5 Salil Tripathi, personal interview with the author, June Citation2017: https://www.writersandfreeexpression.files.wordpress.com/2017/02/interview-with-salil-tripathi3.pdf.

6 The Cold War is only one of the many lineages and contexts that illuminates the story of modernisms in India, the genealogies of which also precede Independence. What’s more, although this work concentrates on English-language writers and journals, I have repeatedly argued that it is impossible to dissociate modernisms in English and in other languages, if only because some of these writers (e.g., Arun Kolatkar, Dilip Chitre, Vilas Sarang, A. K. Ramanujan) were bilingual writers, because so many others are translators, and because many of the editorial platforms at the time (such as the little magazines) worked across linguistic divides. “Poetry India” (which is also the name of a magazine Ezekiel edited in 1966 and 1967, whose six issues published translations from and by modern Gujarati, Panjabi, Kannada, Marathi, Urdu, Hindi, Bengali, Malayalam, and Oriya poets, as well as translations from precolonial traditions) is “Translation India”. These linguistic transactions are also emblematic of “the worlds of Bombay poetry” (Nerlekar and Zecchini Citation2017a).

7 See Jussawalla’s articles “Joys of Xerox” (Jussawalla Citation2014, 229–231) and “Confessions of a Street-writing Man” (Citation2015, 326–328).

8 Unpublished Kolatkar archives, some of which, including this passage, are cited in Zecchini (Citation2014), and were made available by Arvind Krishna Mehrotra and Ashok Shahane. Many of these documents are still in their possession.

9 If A. K. Ramanujan was commissioned by the Ford Foundation to write a report on India, what is less known is to what extent his 1967 collection of translations, The Interior Landscape, owes – albeit indirectly – to the economics and politics of the Cold War. By his own admission, Ramanujan stumbled on a treasure, an anthology of classical Tamil love poems, as he was looking for a grammar of Old Tamil in the uncatalogued stacks of books of a Chicago library basement. Yet the randomness of the discovery is only partial. There is a story behind the story. These books found their way there because of the PL 480 programme: the large wheat loans supplied by the United States to India in 1951, the interests of which were paid in Indian books sent to the United States (Krishna Citation2014).

10 The inaugural conference of the ICCF in Bombay alerts, for instance, to the dangers of “totalitarian propaganda being spread in India through foreign subsidised literature” (ICCF Proceedings Citation1951, 59).

11 This is partly due to the importance of the “Marxist Cultural Movement in India” (see Pradhan Citation1979) and the impact of the Progressive Writers’ Association, on which a lot of scholarship exists.

12 “Today we paint with absolute freedom of content and techniques almost anarchic”, wrote F. N. Souza in 1949 (Dalmia Citation2001, 43), and Gulammohammed Sheikh remembers the “scent of freedom promised by the winds of the modern blowing in the air” (in Garimella Citation2005, 50) in the 1950s.

13 Born in Istanbul to Armenian parents, Nuvart Mehta became a US citizen in 1947, joined the United States Foreign Service and was appointed Cultural Affairs Officer at the USIS in Bombay in 1952. She married a Bombay Parsi, and was in charge of the Bombay office of the Fulbright Commission for several years.

14 Span was a journal on India and the United States published in English, Hindu and Urdu by the US Embassy from the 1960s onwards. The first issue of Perspectives USA distributed in US embassies included Faulkner’s Nobel speech, poems by William Carlos Williams, and translations by Marianne Moore. As both Greg Barnhisel and Leela Gandhi (Citation2001) note, Laughlin also embarked on a project to distribute US books to India and was involved in the Southern Language Book Trust (SLBT) financed by the Ford Foundation.

15 A word used by Justin Quinn in his compelling book on the transnational circulation of Eastern European poetry across the Iron Curtain (Citation2015).

16 Shils was a US social scientist who was also adviser on the CCF’s Indian programme.

17 Many US foundations or organizations also funded the travel of Indian writers such as Nissim Ezekiel or Agyeya to the United States. The importance of the University of Iowa International Writing Program, to which Dilip Chitre, Arvind Krishna Mehrotra, Adil Jussawalla, Jayanta Mahapatra, and Nirmal Verma participated, also requires more study.

18 Partisan Review also received CIA support and was described by Sidney Hook as an effective vehicle for “combatting communist ideology abroad, particularly among intellectuals” (cited by Coleman Citation1989, 135)

19 The participation of Max Yergan, the African-American sociologist at the inaugural ICCF conference, was also a means to showcase, as he argues himself, that “America is free to criticize itself, free to be criticized” (ICCF Proceedings Citation1951, 18).

20 “Who is Cultured?” Quest, No. 24, 1960, 12.

21 Part of this correspondence is available in the special collection of “Hungry Generation papers” at Northwestern University Library.

22 The scandal rocked the journals associated with the CCF throughout the world. Abu Sayeed Ayyub, who edited Quest at the time, wrote a defensive editorial asserting he knew nothing of this “wholly repellent” association:

What doubtful service the CIA did to the CCF has been far outweighed by the unquestionable and immeasurable service it has done to the militant Communist propagandists all over the world … Taking advantage of the wide-spread anti-American feeling in this country, day after day they are dinning in everybody’s ears that all this talk about freedom of art and thought is only CIA cant. (Quest Citation1967, 10)

23 The distinction, which has often been constructed as a sharp opposition, between literatures associated with “experimentalism” and those associated with “progressivism” dates back to the 1930s and 1940s, with the foundation of the pan-Indian Progressive Writers’ Movement, whose manifesto was published in the Hindi journal Hans in 1935 and in the New Left Review a year later. In 1936 Premchand declared: “So long as the content of our writing is on the right lines, we need not worry about the form” (Pradhan Citation1979, 58). Also see Agyeya’s prefaces to his Saptak anthologies (see Agyeya Citation2004), the first of which, Taar Saptak, published in 1943, is credited as having heralded “modernism”, understood here as experimentalism in Hindi, and the April–June Citation1963 issue of Quest, which includes a long discussion entitled “For or Against Abstract Art”.

24 Interview with the author, Mumbai, February 2018.

25 Anti-communism in Quest comes in much more subtle and ambivalent terms than in the ideologically straightforward political platform of the ICCF, Freedom First, founded in 1952 by Minoo Masani, and which Nissim Ezekiel briefly edited in the early 1980s.

26 A point also made in Coleman (Citation1989) and Pullin (Citation2011).

27 “Why should the world, or rather the free world, as it is called, be divided between the shepherds and the lambs? And what does the fight mean to the lambs? Over a hundred million Negros of Africa and millions of Arabs are being ruled today by the free nations of the world … What does the fight against totalitarianism mean to these millions of people?” writes Narayan (ICCF Proceedings Citation1951, 37–38).

28 By 1964, Saunders argues, Cold Warriors

were already walking anachronisms … With the rise of the New Left and the Beats, the cultural outlaws who had existed on the margins of American society now entered the mainstream, bringing with them a contempt for what William Burroughs called a ‘snivelling, mealy-mouthed tyranny of bureaucrats, social workers, psychiatrists and union officials’. (Citation2013, 303)

29 Ezra 3 opens on several reviews, including one by Eric Oatman, editor of manhattan review, calling ezra “a great blast”, but also regretting the “imagist” resonance: “one might suspect without opening the mag that you’re trying to ‘bring back’ the glorious days of early twentieth century poetry – a rather reactionary move”.

30 In a text published in 1963, Ezekiel writes:

I offer my assistance freely, for what it is worth, in the struggle against the ‘processes by which a nation is being made to conform’ … What is required is a struggle for the liberalisation of specific relationships, institutions and contracts. (in Anklesaria Citation2008, 212)

31 See the Winter 1962 issue of Quest, in which Ginsberg’s long poem “Aether” was published. What’s more, Arvind Krishna Mehrotra, Arun Kolatkar, Dilip Chitre and Adil Jussawalla were either published in Quest and/or in Poetry India.

32 Letter dated 20 August 1967. Arvind Krishna Mehrotra Papers, Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University. Reproduced in Journal of Postcolonial Writing 53 (1–2): 200.

33 The May–June editorial of Vrishchik entitled “Against Communalism” also strongly condemns the cynicism and violence of the “big nations”:

We need more than powerful words to describe the world we live in … Whether it is an entire marriage party burnt alive during the communal riots or South Vietnamese prisoners held like animals in ‘tiger-caves’, starved, choked and forced to drinking their own urine. (1970, n.p.)

34 In his preface to The New Poetry, Al Alvarez defines gentility as the “belief that life is always more or less orderly, people always more or less polite, their emotions and habits more or less decent and more or less controllable” (Citation1966, 25).

35 Ginsberg makes a similar diagnosis in a 1977 text called “T. S. Eliot Entered my Dreams” where he describes an imaginary dialogue with the elder poet and criticizes the “domination of poetics” by the CIA because of which an “alternative free vital decentralized individualistic culture” failed to materialize (quoted in Saunders Citation2013, 209).

36 Also see Jussawalla’s article “View of a Volcano with Various Members of the Artistic Profession Warming their Arses on It”, published Vrishchik, where he criticizes the elitist and bourgeois “defensiveness” of the art scene in India (Citation1972b).

37 Quinn (Citation2015) also argued that by outsourcing the political and public voice of literature on the other side of the Iron Curtain, to voices in communist regimes, Alvarez avoided acknowledging the “radical political poetry of the Beats” (141), who were themselves highly admired by East European poets.

38 Dilip Chitre discusses the scramble to claim the nineteenth-century Marathi poet Keshavsut, who is smashed to fragments: “The Marxists hail him as a people’s poet … On the other hand, the cult of pure poets also claims him, and to them he is perhaps the first Symboliste in Maharashtra” (Quest, Autumn 1966, 45).

39 Not only did the Indian little magazines publish texts by Ginsberg, John Cage, Hans Arp, Cesare Paveze, Vasco Popa, Jean Genet, Antonin Artaud, and many other world writers, but they also staged their transnational connections through reviews and excerpts of correspondence. Some of these little mags were also exchanged with similar publications throughout the world.

40 “Consecration” in the sense that Bourdieu talks of certain groups, institutions or authorities that have the power to define, codify and police literary legitimacy. Ezekiel, who served as an editor for so many journals, and to whom a wealth of budding poets sent their texts for advice, certainly represented such a consecrating instance. He was also notoriously particular about grammar, typography and punctuation, something that Mehrotra’s little magazines, like Ashok Shahane’s in Marathi, consciously disregarded.

41 Nerlekar (Citation2016) also opposes the philosophies and agendas of Ezekiel’s magazines and of Mehrotra’s.

References

- Abu Sayeed, Ayyub, and Amlan Datta, eds. 1959 (Jan.–March). Quest, a bi-monthly of arts and ideas. Bombay: The Indian Committee for Cultural Freedom.

- Abu Sayeed, Ayyub, and Amlan Datta, eds. 1959 (April–June). Quest, a bi-monthly of arts and ideas. Bombay: The Indian Committee for Cultural Freedom.

- Abu Sayeed, Ayyub, and Amlan Datta, eds. 1959 (July–Sept.). Quest, a bi-monthly of arts and ideas. Bombay: The Indian Committee for Cultural Freedom.

- Abu Sayeed, Ayyub, and Amlan Datta, eds. 1960 (Jan.–March). Quest, a bi-monthly of arts and ideas. Bombay: The Indian Committee for Cultural Freedom.

- Abu Sayeed, Ayyub, and Amlan Datta, eds. 1960 (Autumn). Quest, a bi-monthly of arts and ideas. Bombay: The Indian Committee for Cultural Freedom.

- Abu Sayeed, Ayyub, and Amlan Datta, eds. 1960–1961 (Winter). Quest, a bi-monthly of arts and ideas. Bombay: The Indian Committee for Cultural Freedom.

- Abu Sayeed, Ayyub, and Amlan Datta, eds. 1963 (April–June). Quest, a bi-monthly of arts and ideas. Bombay: The Indian Committee for Cultural Freedom.

- Abu Sayeed Ayyub, ed. 1967 (July–Sept.). Quest, a Quarterly of Inquiry, Criticism and ideas. Bombay.

- Agyeya. 2004. Selections from the Saptaks. Edited by S. C. Narula. New Delhi: Rupa.

- Alvarez, Al, ed. 1966. The New Poetry. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

- Anklesaria, Havovi, ed. 2008. Nissim Ezekiel Remembered. New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi.

- Appadurai, Arjun. 1996. Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Barnhisel, Greg. 2015. Cold War Modernists: Art, Literature and American Cultural Diplomacy. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Barnhisel, Greg, and Katherine Turner, eds. 2010. Pressing the Fight: Print, Propaganda and the Cold War. Amherst: University of Massachussets Press.

- Brouillette, Sarah. 2015. “US–Soviet Antagonism and the ‘Indirect Propaganda’ of Book Schemes in India in the 1950s.” University of Toronto Quarterly 84 (4): 170–188. doi: 10.3138/utq.84.4.12

- Bulson, Eric. 2012. “Little Magazine, World Form.” In The Oxford Handbook of Global Modernisms, edited by Mark Wollaeger, and Matt Eatough, 267–287. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Chaudhuri, Amit. 2013. Telling Tales: Selected Writings 1993–2013. London: Union Books.

- Chitre, Dilip, ed. 1967. An Anthology of Marathi Poetry (1945–1965). Bombay: Nirmala Sadanand Publishers.

- Coleman, Peter. 1989. The Liberal Conspiracy. The Congress for Cultural Freedom and the Struggle for the Mind of Postwar Europe. New York: Free Press.

- Dalmia, Yashodhara. 2001. The Making of Modern Indian Art: The Progressives. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

- Ezekiel Nissim, ed. 1955. Quest, a bi-monthly of arts and ideas. Bombay: The Indian Committee for Cultural Freedom.

- Ezekiel Nissim, ed. 1956. Quest, a bi-monthly of arts and ideas. Bombay: The Indian Committee for Cultural Freedom.

- Ezekiel Nissim, ed. 1957. Quest, a bi-monthly of arts and ideas. Bombay: The Indian Committee for Cultural Freedom.

- Ezekiel Nissim, ed. 1957–1958 (Dec.–Jan.). Quest, a bi-monthly of arts and ideas. Bombay: The Indian Committee for Cultural Freedom.

- Ezekiel, Nissim, ed. 1962. Indian Writers in Conference. Bombay: PEN All-India Centre.

- Fernandes, Nares. 2012. Taj Mahal Foxtrot, The Story of Bombay’s Jazz Age. New Delhi: Roli Books.

- Futehally, Laeeq, Achal Prabhala, and Arshia Sattar, eds. 2011. The Best of Quest. Chennai: Tranquebar Press.

- Gandhi, Leela. 2001. “The Ford Foundation and Its Arts and Culture Program in India: A Short History” (unpublished document). New York: Ford Foundation Archives.

- Garimella, Annapurna, ed. 2005. Mulk Raj Anand, Shaping the Indian Modern. Mumbai: Marg Publications.

- Ginsberg, Allen. 1968. Planet News. San Francisco: City Lights.

- Greenberg, Clément. 1961. “Avant-garde and Kitsch.” In Art and Culture, Critical Essays, 3–21. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Holt, Elizabeth. 2013. “‘Bread or Freedom’: The Congress for Cultural Freedom, the CIA and the Arabic Literary Journal Hiwar (1962–1967).” Journal of Arabic Literature 44: 83–102. doi: 10.1163/1570064x-12341257

- ICCF (Indian Congress for Cultural Freedom). 1951. Indian Congress for Cultural Freedom Proceedings, March 28–31 1951. Bombay: Kanada Press for the Indian Congress for Cultural Freedom.

- John, V. V., ed. 1970 (April–June). Quest, a Quarterly of Inquiry, Criticism and ideas. Bombay.

- John, V. V., and Parikh, G. D., eds. 1974. Quest, a Quarterly of Inquiry, Criticism and ideas. Bombay.

- Jussawalla, Adil. 1972a. “Boys and Girls in Purdah.” Campus Times.

- Jussawalla, Adil. 1972b. “View of a Volcano with Various Members of the Artistic Profession Warming their Arses on it.” Vrishchik, April–May.

- Jussawalla, Adil. 1978. “Preface.” In Three Poets: Melanie Silgardo, Raul d’Gama Rose, Santan Rodrigues, 5–6. Bombay: Newground.

- Jussawalla, Adil. 2014. Maps for A Mortal Moon, Essays and Entertainments, Selected Prose. Edited by Jerry Pinto. New Delhi: Aleph.

- Jussawalla, Adil. 2015. I Dreamt a Horse Fell from the Sky: Poems, Fiction and Non-fiction (1962–2015). New Delhi: Hachette India.

- Kapur, Geeta. 2001. “Signatures of Dissent.” ART India Magazine 6 (2): 78–81.

- Khakhar, Bhupen, and Gulammohammed Sheikh, eds. 1969–1973. Vrishchik. Baroda: Vrishchik Publication.

- King, Bruce. 1985. “Modern Indian and American Poetry: Some Contacts and Relations.” In From New National to World Literature: Essays and Reviews, 421–441. Stuttgart: Ibidem.

- Knightley, Phillip. 1997. A Hack’s Progress. London: Jonathan Cape.

- Krishna, Nakul. 2014. “The Heron and the Lamprey.” The Point. https://www.thepointmag.com/2014/criticism/the-heron-and-the-lamprey.

- Laughlin, James, ed. 1952. Perspectives USA. New York: Intercultural Publications.

- Mehrotra, Arvind Krishna, ed. 1967–1971. ezra, 1–5. Allahabad: Ezra-Fakir Press.

- Mehrotra, Arvind Krishna. 1970. “Incident versus Experience: Some English and East European Poets.” Allahabad University Magazine, November: 1–8.

- Mehrotra, Arvind Krishna. 2002. “Bombay Poet.” The Hindu, December 1. https://www.thehindu.com/thehindu/lr/2002/12/01/stories/2002120100230200.htm.

- Mehrotra, Arvind Krishna. 2010. “Koffee Korner.” In Akbar Padamsee, Work in Language, 274–279. Mumbai: Mark Publications.

- Mehrotra, Arvind Krishna. 2012. Partial Recall: Essays on Literature and Literary History. Ranikhet: Permanent Black.

- Mehrotra, Arvind Krishna, Alok Rai, and Amit Rai, eds. 1965–1968. damn you: a magazine of the arts, 1–6. Allahabad and Bombay: Ezra-Fakir Press.

- Mehta, Nurvat Parseghian. 1994. Short Stories from a Long Life. Bombay: Self-published.

- Natarajan, L. 1952. American Shadow over India. Bombay: People’s Publishing House.

- Nerlekar, Anjali. 2016. “‘Melted Out of Circulation’: Little Magazines and Bombay Poetry in the 60s and 70s.” In History of Indian Poetry in English, edited by Rosinka Chaudhuri, 190–202. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Nerlekar, Anjali, and Laetitia Zecchini, eds. 2017a. “The Worlds of Bombay Poetry.” Journal of Postcolonial Writing 53 (1–2).

- Nerlekar, Anjali, and Laetitia Zecchini. 2017b. “‘Perhaps I’m Happier Being on the Sidelines’: An Interview with Adil Jussawalla.” Journal of Postcolonial Writing 53 (1–2): 221–232. doi: 10.1080/17449855.2017.1295826

- Orsini, Francesca. 2015. “The Multilingual Local in World Literature.” Comparative Literature 67 (4): 345–374. doi: 10.1215/00104124-3327481

- Pradhan, Sudhi, ed. 1979. Marxist Cultural Movement in India: Chronicles and Documents (1936–1947). Calcutta: National Book Agency.

- Pullin, Eric. 2011. “‘Money Does Not Make Any Difference to the Opinions that We Hold’: India, the CIA, and the Congress for Cultural Freedom, 1951–58.” Intelligence and National Security 26 (2–3): 377–398. doi: 10.1080/02684527.2011.559325

- Quinn, Justin. 2015. Between Two Fires: Transnationalism and Cold War Poetry. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Rakesh, Mohan, K. P. Singh, and Asghar Wajahat. 1973. “Interview with Mohan Rakesh.” Journal of South Asian Literature 9 (2/3): 15–45.

- Rubin, Andrew. 2012. Archives of Authority: Empire, Culture and the Cold War. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Sabin, Margery. 2002. Dissenters and Mavericks: Writings about India in English, 1765–2000. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Sager, Peter. 1966. Moscow’s Hand in India: An Analysis of Soviet Propaganda. Berne: Swiss Eastern Institute.

- Said, Edward. 2000. Reflections on Exile and Other Essays. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Saunders, Frances Stonor. 2013 [1999]. The Cultural Cold War: The CIA and the World of Arts and Letters. New York: New Press.

- Sussman, Jody. 1973. “United States Information Service Libraries.” University of Illinois Graduate School of Library Science occasional papers, University of Illinois.

- Tripathi, Salil, interview by the author. 2017. “From a Very Young Age in Fact, I Used to Collect Books that Were Banned.” https://www.writersandfreeexpression.files.wordpress.com/2017/02/interview-with-salil-tripathi3.pdf.

- Vazquez, Michael. 2011. “The Bequest of Quest.” Bidoun. https://www.bidoun.org/articles/the-bequest-of-quest.

- Whitney, Joel. 2016. Finks: How the CIA Tricked the World’s Best Writers. New York: O/R Books.

- Zecchini, Laetitia. 2014. Arun Kolatkar and Literary Modernism in India: Moving Lines. London: Bloomsbury.

- Zecchini, Laetitia. 2017. “Translation as Literary Activism: On Invisibility and Exposure, Arun Kolatkar and the Little Magazine ‘Conspiracy’.” In Literary Activism: A Symposium, edited by Amit Chaudhuri, 25–55. Oxford: Oxford University Press / Boiler House Press.

- Zecchini, Laetitia. 2019. “Practices, Constructions and Deconstructions of ‘World Literature’ and ‘Indian Literature’ from the PEN All-India Centre to Arvind Krishna Mehrotra.” Journal of World Literature 4 (1): 82–106. doi: 10.1163/24056480-00401005