Abstract

In his book about his Irish–South African family and his childhood under apartheid, White Boy Running, Christopher Hope writes of the “bitter emotion” that infuses the politics of both Ireland and South Africa. This essay considers how the histories of political struggle in both places are intertwined through readings of photographs taken in Ireland and South Africa in the 1970s and 1980s. I draw on these photographs to develop an argument about how affective archives of music, images, and poetry travel across time and space and serve as a conduit for raising awareness about injustice and for forging transnational solidarity. At the same time, these photographs provoke a consideration about how Irish identification with the struggle of black South Africans is complicated by the longer history of British colonialism and racism and how solidarity requires both remembering and forgetting. This essay also begins to trace the presence and work of South African activists in Ireland who campaigned against apartheid while they were in exile.

Seeing sound, hearing pictures

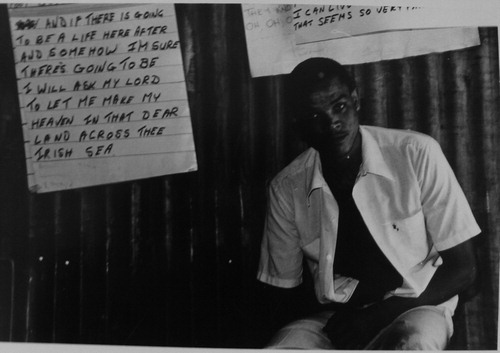

The idea for this essay, which explores some of the connections between Ireland and South Africa through what I describe here as affective archives of sound and image, emerged from the curious presence of the lyrics of the song “Galway Bay” in a photograph I first saw in in Nichts Wird Uns Trennen (Nothing will Separate Us), a book about life under apartheid produced in Bern, Switzerland in 1983 (Koeve and Besserer Citation1983). The photograph, by Paul Konings, who was born in New Zealand but who lived in South Africa during the 1970s and early 1980s, was taken in Hanover Park, an area on the Cape Flats, the large flood-plain to which black residents of Cape Town were forcibly removed under apartheid.

Konings’ portrait shows a man who appears quite young, although his eyes and the anxiety in his wiry frame betray something of the hard life he has led. Inscribed on large sheets of paper that are affixed to the corrugated iron sheets that make up the wall behind him, are the words of the song “Galway Bay”, which conjure the tranquil beauty of the place the song describes, as well as the melancholic longing of diasporic Irish for home. The appearance of the words of this song in this unlikely location seems to be a sign of the history of cultural exchange between Ireland and South Africa. When I looked up the origin of the song “Galway Bay”, which was written by Arthur Colahan, it became clear that it was most likely introduced to South African listeners through the version performed and recorded by the American singer Bing Crosby in 1947, and so perhaps does not indicate as clear a connection between Ireland and South Africa as I first imagined.Footnote1 However, the hopeful lines of “Galway Bay”, which, like many Irish songs, are tinged with an element of loss, take on a redoubled significance in the context of the forced removals from the inner-city neighbourhood of District Six to the wasteland of the Cape Flats ().

Figure 1 Portrait of a man in Hanover Park, Cape Town, South Africa, 1980s. Photograph by Paul Konings, reproduced courtesy of the photographer.

The presence of the lyrics in this photograph conjures not only the unattainable world across the sea, but also the history of forced removals under apartheid. On 11 February 1966, District Six, a neighbourhood in the inner-city of Cape Town, was declared a “whites only” area and the homes and businesses of the sixty thousand people who lived in this vibrant, racially diverse area were demolished.Footnote2 The last forced removals took place there in the early 1980s and most of those who lost their homes were relocated to the Cape Flats. Konings’ portrait led me to think about what Christopher Hope describes as the “bitter emotion” that infuses the politics of both Ireland and South Africa (Citation1988, 52) and how this is perhaps best understood through the ways in which struggles for freedom in both places have been characterized by song and translated into poetic and visual form. While my focus here is on photographs that convey the sounds of struggle rather than on music itself, it would also be possible to trace an aural history of resistance in both placesFootnote3 and it is possible that the man in Konings’ photograph forms part of a troupe of musicians who perform in annual carnivals that commemorate the abolition of slavery at the Cape and that the song forms part of the repertoire of the band.Footnote4 These carnivals began in Cape Town in 1834 and continue today, and the music that is performed at these events draws on and fuses a range of traditions to form the unique sound of the music of Cape Town. This music, known as “ghoema”, has had a profound influence on the genre known as Cape Jazz, made famous through the internationally acclaimed pianist Abdullah Ibrahim (also known as Dollar Brand), who grew up in District Six, where he learned to play piano in a community centre, and later spent many years in exile (Martin Citation2013). The effects of African-American music and culture on South Africa under apartheid are widely recognized, and John Edwin Mason has traced what he terms “the profound influence of African-American culture and political thought on [Abdullah] Ibrahim and the coloured community as a whole” (Citation2007, 25).Footnote5 The connections between music, memory and resistance in Ireland and South Africa, however, remain under-explored. In his study of the history of the carnivals, Denis-Constant Martin notes the diverse names of the troupes that performed at the Carnival that took place in 1907, including the Irish Princes and the Tipperary Coons (Citation1999, 112), as well as the Italian Lifeguards. It is not entirely clear whether these names refer to the mixed-race heritage of the musicians or the provenance of their songs, but it is a sign of the creolized identities of people the apartheid regime classified as coloured and of music as a site of transnational connection. In the context of South Africa under apartheid, the sentimental lyrics of “Galway Bay” articulate longing for what is lost as well as the desire to return to the places from which people have been forcibly removed and thus becomes a subversive song about resilience in the face of ongoing repression.

The book in which Koning’s photograph appears was published during a time of renewed resistance to the apartheid state both within South Africa and internationally. Many of the photographers included in the book were members of Afrapix, an anti-apartheid photography collective founded in 1982, and this was one of several projects involving photographers in South Africa and international solidarity movements that played a significant part in drawing global attention to the anti-apartheid struggle.Footnote6 In the sections that follow I focus on photographs that convey how Irish solidarity with the struggle for freedom in South Africa from the 1960s onwards contributed not only to the international campaign to isolate the apartheid regime, but also shaped events within Ireland. Inspired by and drawing on the work of Tina Campt in Listening to Images (Citation2017), I seek to “listen” to these photographs, to both the silence and the music of the social worlds they evoke. In her analysis, Campt describes how such listening “is constituted as a practice of looking beyond what we see and attuning our senses to the other affective frequencies through which photographs register” (9). I have described above how Konings’ portrait conjures the history of dispossession and its after-effects through the conjunction of the man and the words of the song that appear in the background, both the man and the song technically mute, yet somehow audible. This photograph “hums” with the dense history it portrays and the story it carries is not only that of the harsh reality of life on the Cape Flats, which is visible in the image, but also one of a cultural history in music and experience of oppression that extends back to the time of slavery. It provoked me to think about how both music and photographs travel and how they hold the potential to forge links between disparate places and times, but also how these connections are sometimes less obvious than they first appear. Seeking to unravel the condensed history photographs contain can lead to unanticipated findings, as was the case when I began to explore the affective archives of the Irish anti-apartheid solidarity movement. Engaging with a series of photographs drawn from this archive has made it possible to see how transnational solidarity is formed through exchange and to recognize the central role played by black South Africans in exile, many of whom have been overlooked in dominant accounts of Irish solidarity with the South African liberation struggle.

Irish solidarity with the struggle against apartheid

We fought oppression here for centuries, we’ll help them fight it too. (Christy Moore, “Dunnes Stores”) ()

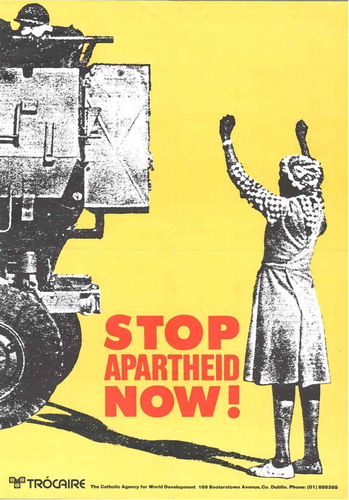

In 1987 Trócaire, an Irish organization established to support struggles for human rights around the world, issued a poster that called on people in Ireland to “Stop Apartheid Now!”.Footnote7 The photo-montage in Trócaire’s poster draws on a powerful photograph of a woman standing with her fists raised in defiance of the presence of the police and the military in the township of Soweto, taken by Paul Weinberg, a documentary photographer and one of the founders of Afrapix. This photograph was taken in July 1985 during the State of Emergency when the apartheid state declared martial law and when photographers were banned from documenting protests and from recording the actions of the police ().

Figure 3 A woman protests against the presence of soldiers in the townships, Soweto 1985. Photograph by Paul Weinberg, reproduced courtesy of the photographer.

International solidarity movements against apartheid, like the International Defence and Aid Fund for Southern Africa (IDAF), made it possible for photographs taken inside of South Africa, which often had a limited circulation within the country, to be widely viewed overseas. It is likely that Trócaire obtained the image through IDAF, which began in 1956 during the Treason Trial and raised funds to cover the legal costs of those arrested for protesting against the state and drew global attention to events like the 1960 Sharpeville massacre.Footnote8 IDAF was identified as an “unlawful organization” by the South African regime in 1966 and although it was banned, the organization provided critical support for the anti-apartheid struggle until the end of apartheid. International organizations opposing apartheid grew in number and intensified their campaigns in the wake of the murder of Steve Biko and the deaths of other political activists who were tortured and killed in detention during the 1970s and 1980s, and as they sought to oppose the executions of political prisoners in South Africa. At the time the poster was issued by Trócaire there was growing support for the anti-apartheid struggle in Ireland, which, as this essay seeks to show, emerged slowly through the long-term efforts of a small number of determined Irish and South African activists.

Irish support for the struggle against apartheid is due, in no small part, to the work of Kader Asmal, the South African lawyer and activist who lived in exile first in London, where he was a founding member of the Boycott Movement and the British Anti-Apartheid Movement, and then in Ireland from the early 1960s, where he worked as a lecturer in law at Trinity College, until the final years of apartheid when he returned to South Africa and served as a minister in the first democratic government.Footnote9 Asmal was a member of the African National Congress and founded the Irish Anti-Apartheid Movement (IAAM) in Dublin in April 1964. He served as Vice-President of IDAF from 1966 to 1981, and in 1976, at a time of intense repression in both South Africa and Ireland, and just a few months before the Emergency Powers Bill was passed by the Irish Supreme Court, founded and served as President of the Irish Council for Civil Liberties, formed “to promote human rights, protect civil liberties, recover them where they have been removed, and enlarge them where they have been diminished” (O’Brien Citation2006, 7). The IAAM drew attention to the brutality of apartheid, campaigned for the release of political prisoners and called for a boycott of South African produce and goods. Asmal argued that,

For historical reasons, Ireland has always manifested an instinctive solidarity with the struggle for freedom in South Africa; the Irish people have themselves undergone the experience of imperial rule and in this century have had recourse to force to free their land and themselves from foreign domination. (Citation1971)

in the first decades of the nineteenth century assimilated into English society; others became acculturated as Dutch or coloured. In the 1890s Irish were to be found on both sides of the political divide, some supporting Boer republicanism and others expressing loyalty to Britain. (Citation2009, 10–11)

In 1978 Asmal led an anti-apartheid march to the Department of Foreign Affairs in Dublin to deliver a letter to the minister Michael O’Kennedy and was interviewed about how the IAAM seemed to be able to bring together even those who held opposing views on the Irish question: “Racism and apartheid”, he states,

is the most crucial issue facing the world today. What happens in Britain for example, with the violence of the National Front, these people feed on South Africa, it feeds them, in England and elsewhere in the world, so therefore we have to focus attention and accelerate our support for the liberation movement.Footnote10

In the section that follows I focus on photographs of the Dunnes stores workers’ strike, which is remembered in Ireland as a significant moment in the history of the anti-apartheid movement there (Boland Citation2013). The archive of documents, film footage and photographs of the strike reveals the role played by trade unions and international workers’ movements and shows how Irish support for the struggle for freedom in South Africa was not a spontaneous form of “instinctive solidarity” but rather, as Asmal himself knew well, and as the story and photographs of the Dunnes strikers shows, was gained through sustained work over time. When the strike began, there were two anti-apartheid organizations in Ireland and by the end of the strike in 1987 there were thirty-six movements campaigning against apartheid in the country.Footnote11 The strike itself certainly played a key role in drawing Irish attention to the South African struggle. However, it is important to recognize the wider context of national and international mobilizing against apartheid in which it took place.

“The power of conscience”Footnote12

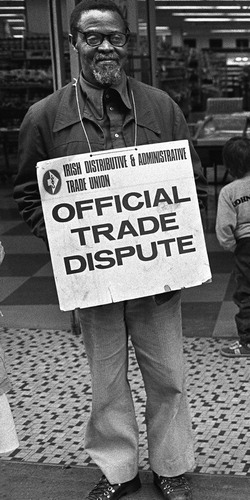

On 19 July 1984, when Mary Manning, a shop assistant at Dunnes Stores and a member of the Irish Distributive and Administrative Trade Union (IDATU), following instructions from the union, refused to sell South African fruit and walked out together with ten other staff members to protest against apartheid, a strike began that was to last two years and nine months. While the workers were optimistic when they began the strike, they were indefinitely suspended from their jobs and were subject to jeers and insults delivered by their former co-workers as they passed them at the entrance to the Henry Street store. The general view, including that of the store managers, was that the strike would soon come to an end. Although the courage of the small group of strikers was recognized by Archbishop Desmond Tutu, and later by Nelson Mandela, it has taken several decades for the Dunnes workers’ strike to be recognized as legitimate and important within Ireland, and the violent response of the gardai; the hostile, racist responses of members of the Irish public; and their tacit or overt support for the apartheid regime is largely overlooked in the broader narrative about the “instinctive” Irish solidarity with the anti-apartheid struggle.Footnote13 Engaging with the affective archives of the Irish anti-apartheid movement illuminates the key role played by South Africans who were in exile in Ireland, England, and other parts of Europe and who acted as conduits for transmitting information, knowledge and the “bitter emotion” of lived experience between places separated by thousands of miles.Footnote14 The contribution of these activists in exile to the international struggle against apartheid has yet to be fully acknowledged.

The Dunnes workers picketed every day and the IAAM organized weekly pickets outside of Dunnes Stores until the Irish government implemented sanctions against South Africa in 1987. In 1984 Archbishop Desmond Tutu invited the strikers to join the picket at South Africa House in Trafalgar Square. In 1985 Tutu invited them to visit South Africa, but they were held at the airport in Johannesburg for several hours and were prevented from entering the country. In 1990 the striking workers were invited to meet Nelson Mandela after his release from prison when he visited Dublin and the significance of their efforts has subsequently been more widely recognized. In March 2008, then-President of South Africa Thabo Mbeki dedicated a plaque to Mary Manning which was later installed outside of the Dunnes Store in Henry Street; Tracy Ryan’s play about the Dunnes workers, Strike!, was first performed at the Samuel Beckett Theatre in Dublin in 2010; the striking workers were invited to attend Nelson Mandela’s funeral; and a film about the strike was released in 2014.Footnote15 Striking Back: The Untold Story of an Anti-Apartheid Striker, Mary Manning’s account of the protest, was published in Ireland in 2017.

The story of the protest provided the subject of Christy Moore’s song “Dunnes Stores” and also forms the focus of “Ten young women and one young man” by folk musician Ewan MacColl.Footnote16 Both songs narrate the history of the strike and inscribe Irish solidarity with the anti-apartheid struggle into Irish national history. Moore’s song emphasizes Mary Manning’s individual moral stand and does not acknowledge Manning’s own perspective, which has consistently emphasized collective action and drawn attention to the significance of the involvement of Nimrod Sejake, whom she describes as “our mentor and hero” (Manning Citation2017, 216). Similarly, the lyrics of MacColl’s song focus on the small group of workers who initiated the strike:

Here’s to the girls of Dublin city who stretched their hand across the sea/that action surely is a lesson, in worker’s solidarity/and here’s to the folk who heed the boycott/who won’t buy Cape and spurn Outspan/and also the lad who joined the lassies/ten young women and one young man.Footnote17

Figure 4 Nimrod Sejake, supporting the Dunnes workers’ strike against apartheid in Dublin. Photograph by Derek Speirs, reproduced courtesy of the photographer.

While Manning does acknowledge the role Sejake played in educating and supporting the strikers, as far as I can tell, there is no comprehensive account of the critical work Sejake did in South Africa prior to his exile, nor of the extensive period he spent working with the anti-apartheid struggle overseas. Engaging with the music, poetry and images that constitute the affective archives of international solidarity movements allows insight into transnational anti-racist organizing and reanimates the names and stories of South African activists such as Sejake, Thobeka Mjolo,Footnote20 David and Norma Kitson, Marius Schoon,Footnote21 Zola ZembeFootnote22 and Benjamin Moloise.Footnote23 Their images and names appear fleetingly in the archives relating to the Irish anti-apartheid struggle and provide a way to piece together fragments of their experiences in exile. At least part of the reason the stories of some of those who played important roles in exile are largely invisible or forgotten is due to power struggles within the anti-apartheid movements, and within the ANC in particular. Sejake, for instance, who was one of the accused in the Treason Trial of 1956–1961, left South Africa and trained in the Soviet Union in the 1960s and then served as a political commissar in ANC training camps in Tanzania. He was convinced that class struggle was central to achieving a just society and argued, contrary to the dominant position held by the ANC leadership of international diplomacy and training people in camps outside of South Africa for armed resistance, for training people to return to South Africa to harness the power of the trade unions and the workers in order to overthrow the apartheid system. In the 1960s he was instructed by the ANC leadership to stop teaching Marxism (possibly because of his involvement with a Marxist group at the University of Dar es Salaam that opposed Nyerere’s ideological position) and was expelled by Nyerere and given seven days to leave Tanzania. He relocated to Zambia, where he worked with leaders of the Pan-Africanist Congress, a South African political movement that was, like the ANC, banned and operated largely from exile, and after travelling to China and Albania, Sejake was deported to Egypt. He received asylum in Ireland in the late 1970s and devoted himself to the workers’ struggle and to opposing apartheid.Footnote24 In his article published in Inqaba Ya Basebenzi, the journal of the Marxist Worker’s Tendency of the African National Congress, Sejake describes “the crisis of leadership” in the ANC and calls for workers to “build the trade unions and transform the ANC” (Citation1983, 10). Sejake’s critique of what he terms “bourgeois democracy” (11) in South Africa remains valid today, and events such as the Marikana massacre of 2012 provide evidence of the post-apartheid state’s collusion with and defence of capitalism. For this reason, it is not surprising that in the 1980s the ANC chose to believe that Sejake was deceased, and that his memory has yet to be resurrected.Footnote25 Sejake’s unwavering commitment to the workers’ struggle is in contrast to Kader Asmal’s more strategic political trajectory. While Asmal initially supported the Dunnes strike, in October 1984 the IAAM withdrew their support and Asmal called on the workers to return to work.Footnote26 It only becomes possible to understand Asmal’s seemingly incongruous call to end the strike when it is read in the light of the tension between the trade unionists and the official line of the ANC in exile, a conflict that fundamentally shaped Sejake’s life. Although Sejake returned to South Africa at the end of apartheid and continued to mobilize workers in Evaton, a township outside of Johannesburg, he never held a position in the post-apartheid government. Asmal, in contrast, became Minister of Water Affairs in the first ANC-led government in 1994 and Minister of Education in 1999.

Between solidarity and sentiment

Songs and photographs that document the history of struggle provide a means for us to access these events in the present, and at the same time they contain an affective charge that is not diminished by the passage of time, but that, in many instances, is amplified by the layering of memory and experience. These affective archives make it possible to trace points of identification and forms of solidarity between the Irish and South African struggles for freedom, and to explore some of the transnational connections that are often overlooked in the writing of national histories. At the same time, these archives can make it possible to see how narratives about political solidarity can be used to obscure or even erase the particularities and significant differences between histories of struggle, and can be instrumentalized in the service of nationalism.

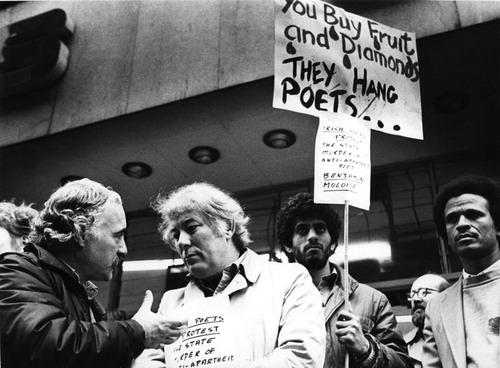

Among the best-known images of Irish solidarity with the movement to end apartheid are photographs and film footage of Seamus Heaney at a protest held in March 1985 to oppose the execution of South African activist and poet Benjamin Moloise. In Eamonn Farrell’s photograph of the protest outside of Dunnes Store, Heaney holds a photocopy of a handwritten sign that reads: “Irish Poets protest the state murder of anti-apartheid poet Benjamin Moloise”.Footnote27 This sign emphasizes the importance of poetry in each place, as well as the transnational connection between poets as those who speak truth to power. Behind Heaney is a protestor holding a sign that connects the Dunnes workers’ strike with the protest against the hanging of Benjamin Moloise: “You Buy Fruit and Diamonds They Hang Poets” ().

Figure 5 Seamus Heaney, Dunnes stores workers and other protestors demonstrating in Dublin to protest against the execution of South African activist and poet Benjamin Moloise. Photograph by Eamonn Farrell, reproduced courtesy of the photographer.

At the time of the campaign to oppose his execution, the name of Benjamin Moloise was known across the world as protests were held in South Africa, the UK, the United States, and Europe. The day before his execution, the Anti-Apartheid Movement held a 24-hour vigil outside of South Africa House in London and Heaney attended the protest in Dublin together with the striking Dunnes workers.Footnote28 After Moloise was executed on 18 October 1985, streets and squares in Italy and France were given his name, but in present-day South Africa there is little to remind people of his story. There are very few photographs of Moloise in public circulation and thus the visual record of protests against his execution is important in preserving his memory.

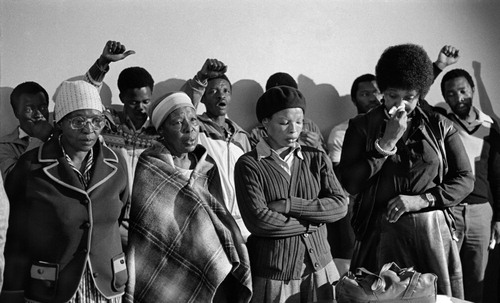

Gille de Vlieg, an activist and member of both the anti-apartheid women’s movement The Black Sash and the photography collective Afrapix, was present at the gathering held at Khotso House in Johannesburg immediately after Moloise was executed, and her photograph of Moloise’s mother, Pauline Moloise, with Winnie Mandela captures the sorrow and resolution of the mourners ().Footnote29

Figure 6 Pauline Moloise, two women and Winnie Madikizela Mandela with other mourners after the execution of Benjamin Moloise, 1985. Photograph by Gille de Vlieg, reproduced courtesy of the photographer.

An article published in the online newspaper Journal.ie (Citation2015) includes a brief documentary about the execution of Benjamin Moloise and includes footage of the press conference held after his death at which Pauline Moloise sings “Oliver Tambo”, the banned resistance song that Benjamin told her he would sing as he walked to the gallows. This is followed by footage of Pauline Moloise and other mourners singing “Nkosi Sikelel i’Afrika”, the anthem of Southern African liberation. Their voices are full of grief and powerfully convey the “bitter emotion” and despair of the time.Footnote30 The seemingly soundless images I have focused on here serve as a way to enter the history they portray and recall the names of activists and the songs that memorialize them.

The singing of the mourners in South Africa is in contrast to the silence of “the world” of mourners grieving the death of Moloise described in Irish poet Desmond Egan’s “For Benjamin Moloise”, which draws a parallel between Moloise and Pàdraic Pearse, an Irish nationalist leader of the 1916 Easter Rising, a teacher and a poet who was convicted of treason and executed by firing squad. The poem includes the lines “together we bow our head/around that stadium of suffering/your death now our bereavement/your courage our abhorrence of every repressor” and the first five stanzas are punctuated by the single line “so that when they hanged you we all became black”. This assertion is followed by these lines:

the hangman peers and hides and looks at his list/we Irish could have warned him that no grave/would go deep enough to hold you/no more than it held Pearse/no more than it could hold any patriot (Egan, Citation1985).

In one sense Egan’s identification with the executed poet can be read as facile appropriation, a far too easy claiming of a condition of being he does not and cannot know. While such a claim may also be an expression of solidarity with the murdered activist and with the struggles of black people more broadly, it marks some of the pitfalls of collapsing the distinctions between experiences of struggle. In universalizing not only the execution of Benjamin Moloise, but also his subjugated position as a black person under apartheid, Egan’s poem instrumentalizes the struggle against apartheid and uses it to reaffirm Irish nationalism. Egan’s trans-historical humanism misses how, at their best, international solidarity movements drew attention to the different ways in which people were subject to oppression in different places. While Kader Asmal sought to awaken what he thought of as the “instinctive solidarity” the Irish should have for oppressed peoples everywhere in order to mobilize political action against the apartheid state, and while the Dunnes strikers repeatedly spoke of how their encounters with South African activists in exile made them aware of how dire conditions of life were in South Africa under apartheid, Egan’s poem collapses under the weight of what might be termed “instinctive sentimentality”.Footnote31

In his essay on music in post-apartheid South Africa, “Political Speculations on Music and Social Cohesion” (Citation2016), Mohammad Shabangu argues solidarity only becomes possible through a willingness to recognize the conditions that separate us as much as those that connect us. The Dunnes workers’ strike drew attention to the general, and generally miserable, conditions of workers under capitalism, and the position of the Irish workers in relation to their own bosses certainly affected their stand against apartheid and may even have played a role in their decision to embark on the strike. At the same time, the strike, which led the workers to become aware of the specificity of apartheid, resulted in what Shabangu describes as “epistemic rearrangement”, at least for those directly involved in the picket (529). One of the effects of the strike was that the workers involved were conscientized about injustice, not only in South Africa, but in Ireland. For instance, in an interview, Cathryn O’Reilly, who was 22-years old when she went on strike, relates how participating in the picket made her aware of the struggles of Travellers, a traditionally itinerant ethnic minority group who only received official status in Ireland in 2017:

At the start we knew very little about South Africa. We were ordinary, working-class people. You got your wages on Friday and you decided where you were going to buy clothes or go dancing at the weekend. Where before you mightn’t have been very interested in politics, it made you very aware of politics and their double standards. It changed your opinion on a lot of things. It made you challenge things.

You were like: “I feel very passionate about this and if I can stand up for people thousands of miles away then I can stand up and speak about injustices here as well”. It made you very aware of the injustices that happen in this country as well. One of the people who came down to the picket line in the early stages was from Pavee Point, the travellers’ [organization]. They have their own form of apartheid against them in this country, the way they are treated. (Cathryn O’Reilly interviewed by Jan Battles, “Striking Against Apartheid”, http://www.rte.ie/tv50/essays/cathrynoreilly.html)

O’Reilly and her fellow striking workers were new to political activity but through their actions they came to meet activists campaigning for justice in Ireland, in South Africa, and across the world, and this served less to affirm their nationalist pride than to challenge it, leading them to question injustice within their own borders.

An unanticipated consequence of both the facile and deep forms of Irish identification with the South African liberation struggle in the 1980s was the pressure the Provisional IRA faced to follow the example of the negotiated settlement. Given this, it was, as Bill Rolston observes, unsurprising that

Labe Sifre’s [sic] song about South Africa “Something Inside So Strong” was adopted as a theme song by republicans in the aftermath of the 1994 cease-fire and was used effectively by Sinn Féin during an election broadcast for the new Northern Ireland Assembly in 1998. (Citation2001, 55)Footnote32

The photographs I have considered here oppose the historical amnesia of sentimental memorializing that would see Irish support for the South African struggle as spontaneous and “natural”, and open a way to understand the critical role played by South Africans in exile in the formation of the Irish solidarity movement against apartheid. These images illuminate some of the connections between struggles for freedom in Ireland and South Africa and offer rich points of access to the histories of racism and anti-racist activism in both places. It is through tracing the “hum” in these photographs, the names and voices of those who are largely forgotten, that it becomes possible to hear their songs and to recall the sounds of resistance. The photographs allow a way to return to the events of the past in order to forge new forms of solidarity against injustice in the present.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the photographers who have granted permission for me to reproduce their images here: Gille de Vlieg; Eamonn Farrell; Paul Konings; Derek Speirs and Paul Weinberg. Thanks also to Cóilín Parsons, Agata Szczeszak-Brewer, Íde Corley, Mohammad Shabangu, Jared Chaitowitz and Tessa Lewin. And thanks to Alastair, Sophie and Jemma Douglas for the music in South Africa, Ireland and everywhere else. This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 838864.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Colahan’s original song includes the lines, “Speak a language that the English do not know/for the English came and tried to teach us their ways/and scorned us for just being who we are”. In the version recorded by Bing Crosby the lyrics have been altered and “English” has been changed to “strangers”. There is also a version of the song called “The Orangeman’s Galway Bay”, the last verse of which runs, “And if there’s going to be a fight hereafter/and somehow soon sure there’s going to be/We’ll make the Fenian’s blood flow just like water/down Belfast Lough into the Irish Sea”.

2 On the history of District Six see Jeppie and Soudien (Citation1990). Throughout the 1920s and 1930s numerous laws were passed which restricted the rights of black people to move freely and to live in urban areas and which prohibited economic advancement and social mobility. The National Party came to power in 1948 and passed the Group Areas Act of 1950, which led to forced removals that were to continue into the 1980s.

3 On music in Ireland, see Smyth (Citation2009); on music under apartheid, see Olwage (Citation2008). The film Amandla! Revolution in Four-Part Harmony (Citation2002) provides an overview of the history of music and the anti-apartheid struggle.

4 Slavery began in South Africa with the arrival of the Dutch colonists at the Cape in 1652 and continued under the reign of the British until 1834. Indentured labour was introduced by the British in 1859 and in 1913 black South Africans were made subject to the Natives Land Act, which allocated over 80 per cent of the land to white people and stipulated that black people could only live within the bounds of “native reserves”.

5 On the influence of American culture in South Africa, see also Nixon (Citation1994). On music in Cape Town, see Duby (Citation2014) and Jaji (Citation2014).

6 On the Afrapix photography collective, see Hayes (Citation2007) and Thomas (Citation2012).

7 Trócaire was founded in 1973 and was the first Irish NGO to support the fight against apartheid. https://www.irishelectionliterature.files.wordpress.com/2012/10/trocaireaparteid.jpg.

8 IDAF grew out of Christian Action, which was created by John Collins in England to assist people who were starving in postwar Europe. The organisation raised funds to support the Defiance Campaign in South Africa in the 1950s and became the British Defence and Aid Fund for Southern Africa after providing support for the legal costs of the 1956 Treason Trialists. In 1965 branches were formed in numerous countries and it became known as the International Defence and Aid Fund for Southern Africa.

9 On the Anti-Apartheid Movement in Britain, see Brown and Yaffe (Citation2014).

10 The interview with Asmal (Citation1978) can be viewed at https://www.rte.ie/archives/2014/0422/610197-irish-anti-apartheid-movement-50-years-old/. The National Front was a British far-right fascist party which gained mass support in the 1970s calling for an end to immigration and inciting racist violence and white supremacy.

11 According to an article about an exhibition commemorating the work of the Irish Anti-Apartheid movement held in Dublin in 2013, an estimated ten thousand Irish people supported the campaign against apartheid. See O’Regan (Citation2013).

12 “I would say that what writers testify everywhere, what they testify to, is some sense of truth, and also to testify to the power of conscience. And we in this country for years, were very acute about an informed conscience and I think what the South African regime is badly in need of is an informed conscience.” Seamus Heaney, speaking at a protest organised by Poetry Ireland in 1985. https://www.rte.ie/archives/exhibitions/2095-dunnes-strike/630140-poets-protest-at-hanging-of-benjamin-moloise/.

13 For some of the hostile responses to the strike, see Manning (Citation2017).

14 South African freedom songs were sung at protests across the world. James Madhlope-Phillips, one of the founders of the cultural unit of the ANC, was in exile in the UK from 1954 and taught generations of activists to sing struggle songs. He also made recordings of liberation songs that reached thousands of people. Madhlope-Phillips was a trade union leader in South Africa and was subject to a banning order by the apartheid state. He left the country illegally and sought refuge in England, where he lived from 1954. In his obituary James Madhlope-Phillips 1919–1987 published in Sechaba, the publication of the ANC, his role in transmitting the songs of the South African liberation movement across Europe is recognised. See http://www.sacp.org.za/main.php?ID=2312.

15 The trailer for the documentary about the strike, Blood Fruit, can be viewed at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W5tIr45nmxw. Additional information about Tracy Ryan’s Strike! can be found at http://www.ardenttheatre.co.uk/strike.

16 Moore’s “Dunnes Stores” can be heard at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TER_M3KNVCE; MacColl’s “Ten young women and one young man” can be heard at https://www.ewanmaccoll.bandcamp.com/track/ten-young-women-and-one-young-man.

17 Reproduced here by kind permission of Ewan MacColl Ltd.

18 Nimrod Sekeremane Sejake was born on 8 August 1920 and died on 27 May 2004. See Irish Times (Citation2004).

19 Speirs worked in London as part of Report, founded immediately after the Second World War by Simon Guttmann. Since 1978, Speirs has documented images of political and social issues in Ireland. His photograph of Sejake is included in an online article about the strike at http://www.thejournal.ie/dunnes-stores-strike-8-3690382-Nov2017/.

20 Mjolo, a South African activist later known as Thobeka Thamage, appears briefly in a news report about the protest against the execution of Benjamin Moloise; see https://www.rte.ie/archives/exhibitions/2095-dunnes-strike/630140-poets-protest-at-hanging-of-benjamin-moloise/.

21 Schoon and David Kitson appear in a photograph in Manning’s book taken by Speirs at a meeting of the Irish Anti-Apartheid Movement in September 1984.

22 A photograph of Zembe marching alongside Manning and other Dunnes strikers appears in a poster calling for people to march for sanctions against South Africa (National Archives of Ireland 2015/88/644). Zola Zembe and Zola Ntambo were names used by Archibald “Archie” Sibeko who, like Sejake, was one of the accused in the Treason Trial of 1956, a trade union organiser and ANC member.

23 An activist and poet hanged in Pretoria Central Prison on 18 October 1985.

24 I have assembled this information from Sejake’s obituary in The Irish Times in 2004.

25 Troupe (Citation2015) notes that Sejake died in relative obscurity in 2004. Sejake lost touch with his family when he went into exile and was only reunited with them after apartheid ended. A photograph of Sejake addressing a group of workers taken in the 1950s appears on the cover of Luckhardt and Wall (Citation1980) and the authors of the book presumed that Sejake was dead.

26 In his study of the ANC and SACP underground, Suttner (Citation2005) writes of how the ANC achieved hegemony. For a concise overview of the ANC in exile, see Bundy (Citation2018).

27 Farrell is an Irish photo-journalist and former photo-editor of the Sunday Tribune. He began to take photographs in 1980 and documented political and social issues in Ireland. Irish photographer Rose Comiskey also documented the Dunnes workers’ strike and other protests during the 1980s. Her photographs can be seen at www.rosecomiskeyphoto.com

28 A video of Seamus Heaney participating in the protest can be accessed here: http://www.rte.ie/archives/exhibitions/2095-dunnes-strike/.

29 de Vlieg’s photograph was included in the exhibition “The Rise and Fall of Apartheid” at the International Center for Photography in New York in 2013.

31 In a 1985 interview Karen Gearon speaks of the strikers having met four South African activists, including Nimrod Sejake and Marius Schoon: “when we see people like that, our battle is nothing to what their battle is.” https://www.rte.ie/archives/exhibitions/1861-strikes-pickets-and-protests/469917-dunnes-stores-strike/.

32 Labi Siffre’s song can be heard at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=otuwNwsqHmQ.

References

- Amandla! A Revolution in Four-Part Harmony. 2002 [film]. Directed by Lee Hirsch. South Africa/USA: ATO Pictures.

- Asmal, Kader. 1971. “Irish Opposition to Apartheid.” United Nations Unit on Apartheid. Notes and Documents No. 3/71, February.

- Asmal, Kader. 1978. Interviewed by Proinsias Mac Aonghusa, ‘Féach’ Report, 24 January 1978 on an Anti-Apartheid March to the Department of Foreign Affairs in Dublin to Deliver a Letter to the Minister Michael O’ Kennedy. http://www.rte.ie/archives/2014/0422/610197-–irish-anti-apartheid-movement-50-–years-old /.

- Boland, Rosita. 2013. “How 11 Striking Irish Workers Helped Fight Apartheid.” Irish Times, December 6. https://www.irishtimes.com/news/world/africa/how-11-–striking-irish-workers-helped-to-fight-apartheid.

- Brown, Gavin, and Helen Yaffe. 2014. “Practices of Solidarity: Opposing Apartheid in the Centre of London.” Antipode 46 (1): 34–52. doi: 10.1111/anti.12037

- Bundy, Colin. 2018. “South Africa’s National Congress in Exile.” In The Oxford Encyclopaedia of African History, http://www.africanhistory.oxfordre.com/abstract/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.001.0001/acrefore-9780190277734–e-81?rskey=mMBCey&result=1.

- Campt, Tina M. 2017. Listening to Images. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Dubow, Saul. 2009. “How British was the British World? The Case of South Africa.” Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 37 (1): 1–27. doi: 10.1080/03086530902757688

- Duby, Marc. 2014. “Alweer ‘die Alibama’? Reclaiming Indigenous Knowledge Through a Cape Jazz Lens.” Muziki 11 (1): 99–117. doi: 10.1080/18125980.2014.893101

- Egan, Desmond. 1985. “For Benjamin Moloise.” Poetry pamphlet Published and Distributed by AFrI. Dublin. http://www.sahistory.org.za/archive/for-benjamin-moloise.

- Guelke, Adrian. 1995. “The Influence of the South African Transition on the Northern Ireland Peace Process.” South African Journal of International Affairs 3 (2): 132–148. doi: 10.1080/10220469509545166

- Hayes, Patricia. 2007. “Power, Secrecy, Proximity: A Short History of South African Photography.” Kronos 33: 139–162.

- Hope, Christopher. 1988. White Boy Running. London: Secker and Warburg.

- Irish Times. 2004. “Tireless Activist Who Spent 30 Years in Exile.” June 19. https://www.irishtimes.com/news/tireless-activist-who-spent-30–years-in-exile-1.1145648.

- Jaji, Tsitsi Ella. 2014. Africa in Stereo: Modernism, Music, and Pan-African Solidarity. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Jeppie, S., and C. Soudien. 1990. The Struggle for District Six: Past and Present. Cape Town: Buchu Books.

- Journal.ie. 2015. “30 Years Ago Dunnes Stores was Involved in Another Worker’s Dispute … One That Shook the World.” http://www.thejournal.ie/dunnes-stores-state-papers-2503432–Dec2015/.

- Koeve, D., and T. Besserer. 1983. Nichts wird uns trennen: südafrikanische Fotografen und Dichter. Bern: Benteli.

- Loftus, Cara. 2015. “Dunnes Stores Strike: 1984–1987 Young Workers Take on the Bosses in Ireland and South Africa.” ROSA (for Reproductive rights, against Oppression, Sexism and Austerity) http://www.rosa.ie/dunnes-stores-strike-1984–1987–young-workers-take-on-the-bosses-in-ireland-south-africa/.

- Luckhardt, Ken, and Brenda Wall. 1980. Organise or Starve! The History of the South African Congress of Trade Unions. New York: International Publishers.

- Manning, Mary. 2017. Striking Back: The Untold Story of an Anti-Apartheid Striker. Cork: Collins Press.

- Martin, Denis-Constant. 1999. Coon Carnival: New Year in Cape Town Past to Present. Cape Town: David Philip.

- Martin, Denis-Constant. 2013. Sounding the Cape: Music, Identity and Politics in South Africa. Somerset West: African Minds.

- Mason, John Edwin. 2007. “‘Mannenberg’: Notes on the Making of an Icon and Anthem.” African Studies Quarterly 9 (4): 25–46.

- Nixon, Rob. 1994. Homelands, Harlem and Hollywood: South African Culture and the World Beyond. New York: Routledge.

- O’Brien, Carl. 2006. Protecting Civil Liberties, Promoting Human Rights. 30 Years of the Irish Council for Civil Liberties. https://www.iccl.ie/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/30–year-anniversary-booklet.pdf.

- O’Regan, Michael. 2013. “Irish Anti-Apartheid Movement Remembered at New Exhibition in Dublin.” Irish Times, April 22. https://www.irishtimes.com/news/social-affairs/irish-anti-apartheid-movement-movement-remembered-at-new-exhibition-in-dublin-1.1369108.

- Olwage, Grant. 2008. Composing Apartheid: Music For and Against Apartheid. Johannesburg: Wits University Press.

- Rolston, Bill. 2001. “‘This is Not a Rebel Song’: The Irish Conflict and Popular Music.” Race & Class 42: 49–67. doi: 10.1177/0306396801423003

- Sejake, Nimrod. 1983. “Worker’s Power and the Crisis of Leadership.” Inqaba Ya Basebenzi 12: 8–13.

- Shabangu, Mohammad. 2016. “Political Speculations on Music and Social Cohesion.” South African Music Studies 34–35 (1): 529–538.

- Smyth, Gerry. 2009. Music in Irish Cultural History. London: Irish Academic Press.

- Suttner, Raymond. 2005. “Rendering Visible: The Underground Organizational Experience of the ANC-led Alliance Until 1976.” PhD Dissertation, University of the Witwatersrand.

- Thomas, Kylie. 2012. “Wounding Apertures: Violence, Affect and Photography During and After Apartheid.” Kronos 38 (1): 204–218.

- Troupe, Shelley. 2015. “Uncovering One of Ireland’s Hidden Histories – Part Two.” http://www.ardenttheatre.co.uk/blog/2015/10/30/dunnes-strike-part-2.