Abstract

“Green Hell” was the nickname frequently given to France’s largest overseas penal colony in French Guiana. This essay explores the slow and difficult recognition of penal heritage in France and its former colonies via the notion of “grey” heritage adopted by Philippe Artières to identify heritage associated with imprisonment and detention. Drawing on the cross-disciplinary field of colour studies, we explore a series of different possible readings of “grey” in order to highlight different ways in which sites can be instrumentalised to both affirm and negate carceral continuities across history and transnationally. Focusing on locations in French Guiana and the Con Dao archipelago in Vietnam, the essay explores the materiality of these spaces, their presentation and their visitors, in order to suggest how “grey heritage” might be developed as a critical and reflexive approach to the carceral past.

Introduction: welcome to green hell

The Iles du Salut (Salvation Islands), like many former prison islands, today represent a tropical paradise. Located off the coast of French Guiana, approximately 11 kilometres from the town of Kourou, the archipelago is comprised of three small islands: Royale, Saint Joseph and the infamous Diable (Devil’s Island), densely covered in palm trees and surrounded by turquoise water. The water is particularly noteworthy in French Guiana, where the silt from the rivers turns most of the coast an unappealing brown.

Seventy thousand convicts were sent to French Guiana between 1852 and 1938. They were sent from mainland France and from overseas colonies, notably those in North Africa and Indochina. However, between 1871 and 1887 the colony was reserved for colonial subjects, with convicts from mainland France sent to New Caledonia. The racist logic behind this was that those hailing from the colonies were better adapted to surviving the tropical climate than a white European population. Alongside deportation of political prisoners and transportation of those convicted of serious and violent crime, a third convict population of repeat offenders was sent to the bagne (common parlance for the penal colony) following the 1885 “loi sur la relégation des récidivistes” (Sanchez Citation2013). At its inception, the bagne was presented as a utopian colonial project aimed at offering offenders the chance of redemption and rehabilitation via the contribution convict labour would make towards colonial development in French Guiana. However, despite taking inspiration from the perceived success of Australia’s use of transportation, French Guiana, in contradistinction to New Caledonia, was predominantly used as a repository for the unwanted citizens of France and its colonies. The last remaining French and North African convicts were repatriated in 1953, whereas the last Vietnamese prisoners were not given passage home until 1954, a process which continued into the 1960s (Donet-Vincent Citation1992). The penal colony thus operated for a hundred years.

Where the islands of Royale and Saint Joseph housed those undergoing additional punishment, particularly those caught escaping (with Devil’s Island reserved for political prisoners), conditions were far healthier than at other sites across the colony, especially the forest work camps such as Charvein, located along the Maroni River. The unforgiving climate, backbreaking labour, poor rations and widespread disease resulted in these sites being nicknamed “green hell” (L’Enfer Vert) and the experience of forced labour in the bagne described as a form of “dry guillotine” evoking a slow, invisible death that contrasted to the quick, bloody spectacle of a Republican-style execution.

Taking this notion of green hell as a starting point, this essay seeks to juxtapose it with the notion of “grey heritage” (patrimoine gris) which has been proposed, somewhat provocatively, by French prison historian Philippe Artières (Citation2018) as an umbrella term for heritage relating to imprisonment. The essay will present a series of engagements with the colour grey in order to identify some of the key sociopolitical stakes of heritage attesting to the history of France’s overseas transportation. The primary focus will be on former sites belonging to the penal colony in French Guiana, where heritage initiatives have been developed since the late 1980s. Detailed attention is given to the Camp de la transportation at Saint Laurent du Maroni and the Bagne des annamites located at Sinnémary-Tonnegrande.

The Iles du Salut are most famously associated with France’s notorious penal colony, particularly within an Anglophone cultural imaginary. However, the Camp de la transportation is the most complex site in terms of heritage development. The camp is located at the heart of the town of Saint Laurent du Maroni, so enjoys an important relationship with different local communities situated in and around the town. The Bagne des annamites (also known as the Camp Crique Anguille) – located about forty minutes’ drive from Cayenne – is one of three former camp sites housing Vietnamese prisoners brought over in 1931 known as Etablissements Pénitentiaires Spéciaux (EPS). The site is an important example of the use of the bagne to relocate (and redefine) colonial subjects (Paterson Citation2018) and comparison will be drawn with the smaller, lesser-known bagne once located on the Vietnamese archipelago of Con Dao (Poulo-Condore), 200 kilometres from the mainland and where both political prisoners and common criminals from throughout French Indochina were sent.

Due to a number of factors, including the widespread use of sites of imprisonment and detention during the various conflicts of the mid- and late twentieth century, along with the ongoing closures of nineteenth-century prison buildings across Europe (notably, the closure of seven prisons in the UK in 2013), prison and penal heritage and related tourism constitutes a growing global phenomenon. The study of this phenomenon represents an emerging sub-field within both dark tourism (Welch Citation2015; Piché et al. Citation2017) and carceral geography (Morin and Moran Citation2015). It is perhaps not surprising that existing studies of penal heritage lay emphasis on the underlying political stakes of these sites. Indeed, and as we shall discuss further, the presentation and interpretation of a site can either serve to affirm carceral continuities with present-day uses of imprisonment or create a marked distance from contemporary practices. Individual prisoner narratives, especially those evoking scandal and sensation, can be instrumentalised to divert attention from the systematic violence of a regime. Analysis of the visual tends to focus on the display of artefacts of torture and restraint alongside mugshot photography. Where an aesthetics of light and dark frequently plays out in the spatial configuration of a former prison turned museum, less attention has been given by scholars to a more nuanced instrumentalisation of colour in these spaces. In taking up the question of colour in relation to former spaces of confinement, this essay echoes the call made by Andersen, Vuori, and Guillaume (Citation2015) for the inclusion of a serious consideration of colour in the field of visual security studies. Their analysis of colour within security practices takes the form of a multimodal social semiotics which emphasizes the ways in which colour operates within a complex system of signs. Colour exceeds specific material, visual and textual markers and is caught up in multivariegated forms of meaning-making which shift over time. In exploring spaces which represent the aftermath of a particular form of security belonging to French colonial occupation, our focus on colour is also intended to bring discussions around heritage restoration and interpretation into closer proximity with the decolonization project of recent years, as it challenges the nineteenth-century legacy of the museum and ongoing museological practices (Soares and Leshchenko Citation2018).

Following this introduction, the essay is composed of four main points of discussion followed by a short conclusion. The first section will consider Artières’ proposed use of the term “grey heritage” within the wider context of dark tourism and France’s relatively recent acknowledgement of former sites of incarceration and detention as “lieux de mémoire” (sites of memory).

The second section then moves from the wider history of prison heritage to the specific architecture of the penal colony and its presentation. While the carceral landscape is frequently defined by a range of colours despite a general prevalence of grey stone and concrete, grey continues to provide an umbrella term for thinking about carceral continuities across time and space. The continuities between the penal and civilian quarters in Saint Laurent du Maroni are considered before a longer comparative analysis of ruins located in Montsinery and on Con Dao. The two sites are historically linked via what might be referred to as administrative “grey zones.” Moreover, the different presentation of vestiges at these sites highlights the need for a nuanced reading of carceral ruination developing Stoler’s claim that the celebration of colonial ruins often obscures other forms of ongoing colonial and neocolonial violence. Moving from the operation of the penal colony to the slow process of its closure, the third section of the essay explores the forgotten, marginalized lives of the libérés (freed convicts obliged to remain in French Guiana following the end of their sentence). The slow violence of their existence is read in terms of Cohen’s notion of “grey ecology,” which provides a fruitful way of exploring the legacy of the penal colony, especially in terms of the liminal subjectivities, habitations and practices emerging after the penal administration withdrew from the territory. The final main section of the essay returns more forcibly to the idea of grey heritage and the exclusions and obfuscations arising between the dual legacies of slavery and convict transportation in French Guiana. To conclude, the question of individual accountability amongst the ruins of the colonial prison is posed.

Defining grey heritage

In an interview given for the 2018 issue of Monumental dedicated to carceral heritage, Artières argues “Between golden and industrial heritage, there is a grey heritage which requires our attention and interrogation.”Footnote1 This suggestion resonates with recent work by Forsdick (Citation2018), in identifying the surprising absence of sites of incarceration from Pierre Nora’s epic Lieux de mémoire (Citation1984–Citation1992) project.

Where Forsdick and Artières emphasize the need to focus on a previously overlooked form of heritage in France’s former penal colonies, the idea of France’s penal heritage collectively constituting “un patrimoine gris” is also worth closer attention. Does the term have any purchase beyond Artières’ use of the expression? Further research suggests it is not presently an established or widely used term. However, the expression “tourisme gris” can be found in a 2011 article “Le patrimoine, c’est un truc pour les vieux … ” by André Suchet et Michel Raspaud. Suchet and Raspaud (Citation2011) translate “tourisme gris” directly from the English “grey tourism” referring to the growing senior-citizen market for tourism organized around museums and heritage sites over and above beach and adventure tourism. The article focuses on the case of the Vallée d’Abondance in the Northern Alps where poor ski seasons led to a shift in focus towards cultural heritage. The main point of reference for the term “grey tourism” is the work of Ashworth and Tunbridge (Citation2005), who use the term in relation to a shifting agenda in Malta during the 2000s.

Artières’ use of “grey” can be situated within an understanding of heritage as a form of “grey tourism” but also implies a different, almost oppositional and certainly more specific, use. It might be argued prison tourism is a key form of cultural heritage that appeals to a wider age demographic due to representing a form of “dark tourism” (Lennon and Foley Citation2000). In this context, we might also read “grey” as implying a shadowy history, yet one that is lighter (indeed, prison museums often engage in a humour not found in museums associated with genocide or atrocity) than is found or represented at other sites of suffering.

Taken in its material sense, “grey” makes direct reference to the grey stone and later concrete structures that commonly define penal architecture. It also evokes a form of architecture that inhabits a grey zone, since it suggests both the quotidian banality of the prison experience for many as well as the moral paradoxes of a form of punishment that is often seen as being all at once too cruel (Donet-Vincent Citation1992), too gentle (Redfield Citation2000, 78), too expensive (Toth Citation2006, 101) and too ineffectual as either punishment (101–102) or mode of colonial expansion (Londres Citation1924, 79). These are all criticisms that were at some time or another levied at France’s penal colonies in both French Guiana and New Caledonia. Former sites of incarceration and internment can be presented in terms of a rupture with the past as such, constituting examples of processes of decarceration or former political regimes that have since been dismantled. But they can also invite us to make connections with present systems and their continued use of practices such as solitary confinement and physical restraint, as well as the displacement of individuals, if not overseas, then away from their families and communities. Indeed, Artières goes on to argue the value of prison heritage lies as much in the role of the sites as producing knowledge (savoir) about those being held as it does in presenting us with a history of bodily constraint. This is of course a direct reference to the stakes of Michel Foucault’s Discipline and Punish (Citation1977).

Foucault wrote his seminal text on the birth of the prison at a time when disciplinary modes of power and, particularly, the prison in its existing form, seemed to have run their course. In an interview given in Japan in 1978, he claims these forms of power so effective during the nineteenth century are beginning to lose their relevance, giving way to increasingly complex, variegated identities and social activities (Foucault Citation1978, 533). Yet while he may not have anticipated mass incarceration or even the persistence of traditional disciplinary models of imprisonment, he did identify the ingenuity of the prison in that its failure makes the best case for its continued use and operation, albeit in modified forms (Citation1977, 277). A counterpoint to this is to make visible the historical contingency of the prison and related forms of policing which emerge to protect bourgeois capital and, in particular, colonial gains. Might the role of grey heritage include this task of rendering visible?

Artières insists the prison must be considered as part of France’s “Grande Histoire” rather than being considered as an exceptional, marginal history. This notion of “exceptional” history resonates with the way many former sites have been presented within a French context as exemplified by the Conciergerie, Chateau d’If and the exotic Iles du Salut. The Conciergerie in Paris where Marie-Antoinette was held prior to her beheading is presented almost as a shrine to the last queen of France. More problematic perhaps is the organization of the exhibition at the Chateau d’If off the coast of Marseille around its most famous yet fictional inmate, the Count of Monte Cristo. Numerous political prisoners including various communards were actually held there, yet their story is relegated to a few cursory references on the upper level of the chateau.

Artières’ call to position penal institutions at the centre of France’s “Grande histoire” is significant because it implies he considers heritage as having the potential to engage visitors in more general debates around the persistence and future of prison as a response to illegal activity (what Foucault referred to as “illegalismes”). The idea that incarceration cannot be seen as separate to the wider socioeconomic structures defining the history of capitalism and colonialism seems incredibly important and urgent. However, we cannot fail to notice how the very idea of a “Grande Histoire” seems at odds with other attempts to explore the impact of incarceration outside of the grand narratives of its inception and even the stories of criminal geniuses, political heroes and falsely accused yet resourceful escapees that frame most historic sites of incarceration. Even a critique of the notion of Grande Histoire requires larger-than-life heroes as narrators. In the case of the bagne, such figures as Alfred Dreyfus, Henri Charrière, René Belbenoit, Francis Lagrange and Paul Roussenq are invariably white (and male) and through privilege, position or political advocacy were able to make it back to France or to the United States to tell their version of events. It is this framing that Martinican writer Patrick Chamoiseau contests in his evocation of the traces-mémoires (memory traces). In the Americas, Chamoiseau suggests, History, Memory and Monument all work to legitimise the crime of colonialism. Chamoiseau opposes this History with a capital “H” to the memory-traces, conceived as spaces, ruins, symbols, silences, as forgotten practices and missing peoples all of which have been effaced by official monuments (Chamoiseau and Hammadi Citation1994, 14, 17). On visiting French Guiana in the early 1990s, Chamoiseau identifies the chance to locate these traces within the ruins of the former penal colony.

More and ongoing work is thus needed to bring these positions, that of Artières and of Chamoiseau, together in such a way that not only provides a more nuanced retelling of the history of prison and penal colonies, but also a retelling that is predicated on a future which ceases to take imprisonment and displacement as a given. Since the role and operation of incarceration is often determined in part by public perception and indeed a public fascination with prison as a site of all manner of “imagined” activities, subjectivities and relations, the visual iconography (Carrabine Citation2010) of imprisonment past and present is of key importance in determining public attitudes on incarceration. We need to think the role of penal heritage alongside that of other cultures of punishment in their creation and interpellation of what Michelle Brown (Citation2009) has termed the “penal spectator.” At the same time, the respective positions assumed by Chamoiseau and Artières both lend themselves to co-option by state-sponsored heritage initiatives concerned with managing and containing public discourses around France’s colonial history. A more radical critique is thus necessary.

The grey substance of ruins

As suggested above, the term “grey” can provide a useful metonym for thinking about the specific materiality or materialities of penal heritage. Yet to reduce penal heritage to the greyness of the crumbling architectural structures of former prisons, cells and dungeons is to reduce these spaces to a lack of colour, to play into an aesthetic which is all too familiar, but which allows us to remain all too distant. It is to encourage a lack of imagination similar to the one that edits out the sounds and smells of life in the penal colony. In Saint Laurent du Maroni, the Camp de la transportation was painted once every four years, frequently in a bright shade of pink. The tour guides make much of this detail. Saint Laurent du Maroni was known as “Le Petit Paris” and the “quartier pénitentiaire” was no exception to this. Today, there is a strip on display which shows as many layers as could be successfully excavated: twelve layers can be counted out of a possible twenty-four or twenty-five (). It is easy to think of the history of the bagne as a single moment in time. Even with a detailed chronology to hand, it is difficult to grasp its longevity. In his account of the ongoing restoration works conducted within the camp during its operation, architect Pierre Bortolussi offers further details of the multiple colour schemes adopted, posing the question as to how restored architecture should be presented:

Surveys showed successively white, white-ochre, ochre-yellow then ochre-pink distemper. The foundations were red, black or light grey. The metal work was, originally, tinted grey then white, yellow, pink and finally light grey. (Bortolussi Citation2018, 70)

Figure 1 Excavated paintwork at the Camp de la transportation, Saint Laurent du Maroni (June 2018). Photo with kind permission of Claire Reddleman.

We question whether a skewed attentiveness to colonial memorials and recognized ruins may offer less purchase on where these histories lodge and what they eat through than does the cumulative debris which is so often less available to scrutiny and less accessible to chart. (Stoler Citation2013, 7)

The architecture of houses, the use of verandas, wrought ironwork, the systematic organisation of outhouses behind the villas and the uniformity of their appearance by the small brick walls which surround them bear witness to the authoritarian role of the district upon the rest of the town. (Coquet Citation2013, 64)

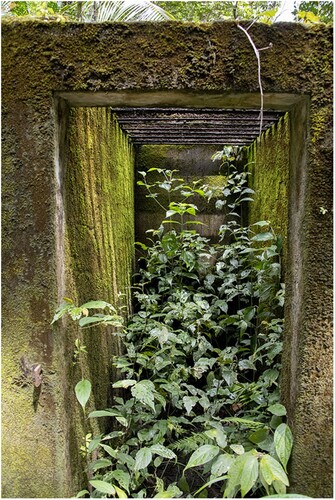

In its common usage, ruins indicate privileged sites of reflection – of pensive rumination. Portrayed as enchanted, desolate spaces, large-scale monumental structures abandoned and grown over, ruins provide a favored image of a vanished past, what is beyond repair and in decay, thrown into aesthetic relief by nature’s tangled growth. (Stoler Citation2013, 9)

What is striking is how the two sets of structures both emphasize continuity across colonial spaces yet their ruins attest to completely different conceptions of time. On Con Dao the preservation of the tiger cages complete with mannequins emphasizes the use of such technologies of confinement and torture within a relatively recent history. Their presentation is also quite deliberately juxtaposed with the American camp located about a kilometre down the road. Signposts direct visitors to the “American tiger cages,” making the point that similar technologies of punishment were employed by the different occupations. Old world colonialism is thus displaced by new world imperialism. Both rely on the prison island and its cellblocks. Both are visible markers of Artières’ concept of grey heritage, but call on an expanded understanding of power-knowledge beyond Foucault’s focus on Europe to incorporate the colonial prison, penal colony and reeducation camp. Stoler has referred to this expanded understanding in terms of a “carceral archipelago of Empire” (Citation2016, 78).

Figure 2 Vestiges of a cell at the Bagne des annamites, Montsinery-Tonnegrande (June 2018). Photo with kind permission of Claire Reddleman.

Figure 3 View of “tiger cage” cell from above, Con Dao, Vietnam (September 2018). Photo taken by author.

The stone architecture of the French penal administration that was built to last is nevertheless replaced by the temporary concrete structures of a new world order in which the ability to assemble prisons, camps and detention centres rapidly requires flat-packed, shippable technologies supplied by industry back home rather than built from scratch by on-site convict labour. The notion of grey heritage can thus be called upon as a means to identify not only continuities between different colonial spaces but also different colonial and postcolonial temporalities. On Con Dao the “grey” of grey heritage emphasizes the near-seamless transition from European colonialism to US imperialism. Grey stone structures (where these have not been painted yellow or pink) give way to grey concrete ones. It is grey which describes the landscape in which military industrial and prison industrial complexes merge, making it difficult to work out where one begins and the other ends.

To define heritage as grey is thus to emphasize the administrative decisions, paperwork, bureaucracy which underpins an architectural history of incarceration. Artières is making an important point when he insists on the role of the prison museum as commemorating not merely an exceptional or marginal site of suffering filled with the irregular, the abnormal or the deviant but, rather, as one that is central to France’s “Grande Histoire” in which all bodies are subjected. What emerges, what grey brings to light, is the historical contingency of imprisonment and confinement as response to definitions of illegality which emerge in relation to shifting demands of the shifting requirements of capital and empire.

Grey thus involves the homogenisation, a rendering banal and assumed but at the same time implying obfuscation, a fudging of details, blurring of lines. The carceral continuities which see the same architectural structures erected in French Guiana and on Con Dao and the widespread use of the “barre de justice,” a relic of the dockyard prisons, in blockhouses throughout France’s penal colonies are supplemented by legal exceptionalism which works to redefine colonial subjects within shifting political contexts. Perhaps the best-known evocation of the process of blurring is found in Primo Levi’s account of the “grey zones” in The Drowned and the Saved (Citation1988) whereby one’s survival in Auschwitz occurred at the expense of the lives of others. Such grey zones might also be located in the wider landscape of camps, the use of which extends far beyond the Nazi use of extermination and concentration camps (in terms of both geography and history). Writing in Le Monde in Citation2017, former Minister of Justice and outspoken critic of both the death penalty and France’s prison system Robert Badinter described the operation of the bagne during Vichy as “a veritable hecatomb” and a crime against humanity that has until recently been largely overlooked.

Many of the Indochinois convicts transported to the forest camps of French Guiana in 1931, including the Bagne des annamites, had originally been classed as political prisoners. The transfer was intended in part to deal with overcrowding in French colonial prisons across the region, as well as to remove a number of anticolonial actors from Indochina. At least eighty of those deported to French Guiana in 1931 were involved in the 1930 Yen Bay mutiny. As political deportees sent to French Guiana were usually exempt from labour according to the political decree of 1850, this status had to be revoked to ensure the maximum labour force possible. Consequently, those arrested on suspicion of specific acts of violence or property damage were reclassed as common criminals. Described by Dedebant and Frémaux (Citation2012, 7) as “little arrangements between governors,” this was not simply a sleight of hand but written into legal codes.Footnote2 The importance given to this population of prisoners as workforce is further emphasized in the care taken by the administration to ensure the new camps avoided the sanitation crises of earlier camps such as Saint Georges and Ilet la Mère (18–19). These measures included the careful medical examination and vaccination of the prisoners before departure from Indochina (10–11).

Reading files belonging to those sent to the EPS and now housed in the Archives Territoriales de Guyane, there is small comfort to be found in reading “Evadé (escaped)” marked in red at the top of many of the individual dossiers (ATG Citation1946–1948). However, as indicated earlier, many of the Vietnamese sent to French Guiana had to wait until the 1960s to be repatriated. Others found new lives amongst the Chinese traders in Cayenne, quietly accepting the racial stereotypes and assumptions required to ensure economic stability at a remove from the city’s Creole and white metropolitan populations. This disappearance from view, this relegation to a life in the shadows, embodies Rob Nixon’s (Citation2011) definition of “slow violence.” The colour of this violence is grey.

Grey ecologies

Pursuing a narrative of slow violence that extends the legacy of the penal colony well beyond its operation, it becomes useful to return to our original juxtaposition of grey and green and the role both colours play in simultaneously effacing and maintaining French colonial violence following the reclassification of French Guiana as an overseas department of France in 1946. Aerial views of French Guiana offer it up as incontestably green, with the majority of the territory covered in primary rainforest that when viewed from above resembles broccoli-like florets. Moreover, secondary rainforest has reclaimed many of the sites once cleared to make space for work camps belonging to the penal colony. However, it is all too easy to think of this reclamation in terms of a “return” to nature which erases the very existence of some of the most brutal work camps from the surface of the territory. The championing of the territory as symbol of French ecological pride via the lexicon of “green” affirms the bifurcation of nature and culture warned against by Latour (Citation2004). Drawing on the project for a “prismatic ecology” developed by Cohen (Citation2013) and others offers an alternative approach to reading the postcolonial space of French Guiana.

According to Cohen (Citation2013), “Color is not some intangible quality that arrives belatedly to the composition but a material impress, an agency and partner, a thing made of other things through which worlds arrive” (xvi). However, the tendency to privilege “green” when thinking of nature (or, more precisely, Nature) and ecology tends to endorse unproductive binaries between nature and culture (Latour Citation2004).

Nardizzi (Citation2013) identifies the role of the colour green in enforcing a certain image of “nature” as stemming from “a genetic fantasy dreamed by white privilege” (148). In other words, the term “green,” particularly when used alongside ecology, describes a human conception which is really nothing more than a frame for human, and more precisely colonial, activity and interaction above all else. Nugent’s study (Citation2007; see also Citation1993) of the history of representation of the Amazon by anthropologists and in popular culture more generally identifies the “accumulation and aggregation” of certain stereotypical images and figures with the idea of “green hell” providing the backdrop to these. In the context of French Guiana, Spieler (Citation2012) has argued it is precisely through the absence of buildings and infrastructure at sites once under the jurisdiction of the penal administration, along with the erasure of different indigenous and migrant populations, that we should understand the legacy of the penal colony.

A “grey” ecology might be called upon to provide a more holistic understanding of the links between the administrative grey zones created by the colonial authorities and the grey architectures and technologies of punishment that endure as ruins within the former penal colony. It might also help us locate the absent, missing humans. The idea of a grey ecology set out by Cohen (Citation2013) is apocalyptic but one which eschews our apocalyptic fantasies – it is a dying out, a fading rather than a light-filled explosion. But a dying out also embodied by a refusal to die. It is not the ruins of the penal colony that refuse to die but our refusal to let them die. All heritage involves a certain conjuring up of ghosts. Penal heritage calls upon those who were never allowed properly to die. Instead, they were simply disappeared, buried alive or left to rot.

In 1951 the photographer Dominique Darbois arrived in French Guiana in search of the Tumac-Humac. She did not anticipate encountering the vieux blancs (old white men), former convicts who had opted not to make the journey back to Europe, or the abandoned penal administration buildings, the degradation of which was rapidly accelerated by the tropical climate (Sanchez Citation2010). Large screen prints reproduced from Darbois’ photos now hang from the ceiling of the Musée du bagne located in the former kitchen at the Camp de la transportation in Saint Laurent (). Several of these feature former convicts, the libérés, prematurely old, topless, heavily tattooed, emaciated men. Known as the vieux blancs, although not necessarily white or from the Metropole, their weather-beaten skin and faded tattoos gives them a washed out, grey appearance in Darbois’ photographs. Their presence in and around Saint Laurent pre-dates the closure of the bagne in the late 1940s. After their sentences were completed, convicts were not simply repatriated to France or other colonies. A system of “doublage” intended to shore up colonial development meant they had to serve the same length of their sentence again on the colony. For those condemned to eight years or more, this became life. Opportunities for sustainable livelihood were limited in a territory possessing swathes of free convict labour. Worn out and sick from their time in the bagne, most of these men were unfit to work and relied on charity to survive.

Figure 4 Musée du bagne, Camp de la transportation, Saint Laurent du Maroni (June 2018). Photo with kind permission of Claire Reddleman.

The museum is not air-conditioned and relies on a breeze blowing through its open doors. The near-transparent screen prints blow precariously, emphasizing the fragility of their subjects. A fragility that is at the same time a form of endurance. At other times when there is less wind, they simply float suspended. The men featured resemble ghosts haunting the space they could not leave even when they finally could. Within the museum the story of the last living convict is recounted. Ali Belhouts died in Algeria in 2007 after being repatriated to Annaba. In an interview given in 2005, he claims that every night he dreams he is back in Cayenne: “when I think about it, I get vertigo, I spent my life there” (cited in Pierre Citation2017).

The biggest irony of all in defining penal heritage as “grey” perhaps comes with the repatriation of the last batches of French convicts. While there was little reason to stay in Saint Laurent, many found the grey, cold skies and buildings of France difficult to adjust to. As Danielle Donet-Vincent writes citing an account from M. Durand of the Salvation Army:

The liberated convicts often arrived wearing their straw hat, a shirt or thin jacket. They all felt the cold. Many of those who disembarked in Winter took in the countryside with trepidation: ‘But what happened here? … Everything is black … There are no leaves on the trees … Have there been fires everywhere? … ’ These men who had returned from the humidity of the equator, from the luxuriance of the forest boasting every shade of green, where the sun made each scale of the morphos wings sing … no longer recalled the winters that stripped the trees, the dark sky or the cold. (Donet-Vincent Citation1992)

Grey heritage is white heritage is dark heritage

So far we have adopted the colour grey in order to highlight processes of blurring, the banality of the administration together with the underlying and often slow violence of the penal colony. In adopting the notion of grey heritage how do we also maintain a critical distance, a reflexive position in relation to the racial politics not only of practices of transportation and incarceration which emerged following the abolition of slavery, but also in the framing of heritage and the exclusions frequently enacted by heritage practices and discourses?

There is a racist logic underpinning the closure of the penal colony, something downplayed in the museum in favour of the humanitarian narrative in which investigative journalist Albert Londres and Salvation Army officer Charles Péan are the protagonists. Omitted in the original newspaper edition appearing in Le Petit Parisien, Londres’ report on the penal administration includes a damning indictment of its director, Herménégilde Tell, whom Londres emphasizes is “un nègre” (Citation1924, 141). In a report dated 11 April 1946, Inspector Perreau warned that release of the convict population and the impossibility of regulating access to previously closed sites offered a “spectacle” that would no doubt be exploited by individuals “more or less” qualified to “inspect” the penal colony (in other words, the international press) (ATG Citation1945–1946). Perreau imagines the future publication of photographs in various New York newspapers featuring impoverished former white convicts looked down upon by black members of society with the caption reading “Colonial France.” It is perhaps this reversal of racial hierarchies and fortunes within the colony that constituted the main source of shame for France’s colonial administration and the only real reason the operation was deemed a failed project.

Today, black heritage (the history of slavery) and grey heritage (the history of the penal colony) are kept both separate and conflated within French Guiana. For example, in Cayenne, former sites relating to the penal colony have been lost while former habitations Vidal and Loyola belonging to the slave-trade era have been excavated and preserved. There is confusion about the objects (such as shackles) and monuments (the statue of the bagnard commissioned by former mayor of Saint Laurent Léon Bertrand) called to represent these distinct phases in the territory’s colonial history. Yet there is also a lack of understanding about the continuities existing between the slave trade and convict transportation. Although the Camp de la transportation now boasts multiple municipal and community functions including a theatre, library and multimedia lab in addition to museum and exhibition space, as a historical monument the site is considered a space of limited interest to the Creole, Amerindian and Maroon populations. There is also little recognition of the social cleansing that saw families renting the space moved to other sites. Their stories now represent an aporia in the history of both the camp and the town. Likewise, other spaces around Saint Laurent that bear witness to an ongoing history of displacement and social cleansing are imbued with silence and forgetting (Léobal Citation2019). These include the Camp de la relégation at Saint Jean (now an enormous military barracks), which operated as a refugee work camp after the Second World War and the camps set up for Surinamese refugees during the Interior War of the late 1980s.

Grey heritage must not only bear witness to White history via the privileging of the stories of suffering of white subjects imprisoned and transported to the colonies. It must not merely insert the history of imprisonment into the larger history of France and its colonial project but, rather, work to deconstruct this history. There is an urge to view the end of the penal colony as a moment of decarceration, the end of a system of punishment and, as such, to insert it into a longer history of abolition(s). But, in doing so, caution is required. The legacy of the bagne, its heritage, consists not only in the buildings and ruins that have been preserved and classed as historic monuments.

Grey heritage is not only White heritage in its focus on the stories of white prisoners or its assumption of predominantly white audiences. It is also white in its obfuscation of the racist underpinnings first of convict transportation and second of its abolition. This, and not simply its testament to human suffering, is why grey heritage is also dark heritage.

Conclusion: devoid of colour

Drawing on existing colour studies, I have suggested ways in which the concept of grey heritage can develop a critical, reflexive approach to the interpretation of heritage associated with convict transportation and former penal colonies. This approach might include making visible the historical contingencies of imprisonment and displacement. It might also draw our attention to previously ignored grey zones, texts and spaces that redefine individuals and the “grey” souls these produce. However, there is also the risk that grey heritage might work to affirm and maintain these ecologies of punishment, whether this is via the abandoned and overgrown ruin or the carefully curated state-sponsored museum housed in restored prison buildings. It is worth noting the obvious limitations of a study built around the lexicon of “grey” (or “gris” in French), predicated on Eurocentric taxonomies of colour. Such limitations might be further situated within what Herwitz (Citation2012) has called the “heritage of heritage”, namely the idea that heritage as bound up in the collective memory and identity of the nation-state remains an essentially colonial endeavour. Nevertheless, sites of penal heritage can provide spaces in which the ongoing use of incarceration and, indeed, extraterritorial detention can be actively contested. While heritage practitioners are required to navigate between a growing abolitionist movement and the ongoing emphasis on “punishment” within many so-called western democracies, the museum visitor also bears a responsibility to interrogate the desires and pathologies that make penal tourism so appealing.

When I visited the Bagne des annamites in 2018 and again in 2019 I was accompanied by a blue morpho which came close yet refused to pause long enough to be photographed. Its presence pierced the subdued green and brown of the forest with a blue so striking it left no doubt as to its status as one of the most famous butterflies found in the Amazon region. During the operation of the penal colony it was avidly hunted by convicts due to the high prices offered by collectors. Yet the most fascinating thing about the blue morpho is the lack of blue pigment in its wings. Its colour is produced solely through the reflection of its microscopic diamond-shaped scales.

I want to suggest that the blue morpho offers a metaphor with which to understand some of the tensions of grey heritage further. We have left largely unexplored the idea that grey is boring. Something is required to disrupt the banality of punishment, to make the grey interesting and worthy of our attention. As Henri Charrière (Citation1969) recognized in his appropriation of the butterfly as personal insignia, the blue morpho represents the spectacle, the sensational, the exceptional within the penal colony. But unlike the vieux blancs drained of colour, the blue morpho is devoid of its own colour, its own content. Instead, it reflects the light back to us. Bound up in the concept of grey heritage outlined above is the call not only for a reflexive, critical approach towards the presentation of heritage, but also for recognition of our accountability as consumers of this heritage. The story of the penal colony along with that of penal history more generally reflects back to us our own fantasies, our own obsessions, our own pathologies as penal spectators.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Unless otherwise stated all translations from the original French are the author's own.

2 Articles 7 and 365 of the penal code, quoted in letter from the Governor of Cochinchine to the Governor General of Indochina, 22 March 1937 (ANOM Citation1915–1952).

References

- Archival sources

- Archives Nationales d’Outre Mer [ANOM]. (1915–1952). 1 HCI 694 Poulo-Condore (1915–1952).

- Archives Territoriales de Guyane [ATG]. (1946–1948). 1Y – EPC – Correspondances (1945–1946). IX 73 (Série Y) – Établissements Pénitentiaires (Convoi d’Indochine No. 19–259 (1946–1948)).

- Andersen, Rune, Juha A. Vuori, and Xavier Guillaume. 2015. “Chromatology of Security: Introducing Colours to Visual Security Studies.” Security Dialogue 46 (5): 440–457.

- Artières, Philippe. 2018. “Entretien avec Philippe Artières.” Monumental 18: 1.

- Ashworth, Gregory John, and John E. Tunbridge. 2005. “Moving from Blue to Grey Tourism: Reinventing Malta.” Tourism Recreation Research 30 (1): 45–54.

- Badinter, R. 2017. “Le Bagne de Guyane, un crime contre l’humanité.” Le Monde, November 24.

- Bortolussi, Pierre. 2018. “Les travaux de restauration.” Monumental 18 (1): 68–70.

- Brown, Michelle. 2009. The Culture of Punishment: Prison, Society and Spectacle. New York: New York University Press.

- Carrabine, Eamonn. 2010. “Imagining Prison: Culture, History, Space.” Prison Service Journal 187: 15–22.

- Chamoiseau, Patrick, and Rodolphe Hammadi. 1994. Guyane: Traces-mémoires du bagne. Paris: CNMHS.

- Charrière, Henri. 1969. Papillon. Paris: Gallimard.

- Cohen, Jeffrey Jerome2013. Prismatic Ecologies: Ecotheory Beyond Green. Minneapolis: Minnesota University Press.

- Coquet, Martine. 2013. “Totalisation carcérale en terre coloniale: la carcéralisation à Saint-Laurent-du-Maroni (XIXe–XXe siècles).” Cultures & Conflits 90: 59–76.

- Dedebant, Christèle, and Céline Frémaux. 2012. Le Bagne des Annamites: Montsinéry-Tonnégrande. Guyane: L’inventaire.

- Donet-Vincent, Danielle. 1992. La Fin du Bagne: 1923–1953. Paris: Éditions Ouest-France.

- Forsdick, Charles. 2018. “Postcolonialising the Bagne.” French Studies 72 (2): 237–255.

- Foucault, Michel. 1977. Discipline and Punish: Birth of the Prison. London: Penguin.

- Foucault, Michel. 1978. “La société disciplinaire en crise.” Asahi Jaanaru 20 (19). 12 May. Reproduced in Foucault, Michel. 2001. Dits et écrits II. 1976–1988. Paris: Quarto/Gallimard.

- Harkin, Tom. 1970. “The Tiger Cages of Con Son.” Life 69(3): 26–29.

- Herwitz, Daniel. 2012. Heritage, Culture and Politics in the Postcolony. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Latour, Bruno. 2004. Politics of Nature: How to Bring the Sciences into Democracy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Lennon, John, and Malcolm Foley. 2000. Dark Tourism: The Attraction of Death and Disaster. London: Continuum.

- Léobal, Clémence. 2019. “Le logement social en situation postcoloniale. État social, impérialisme et ségrégation à Saint-Laurent-du-Maroni, Guyane.” Métropolitiques, November 4. https://www.metropolitiques.eu/Le-logement-social-en-situation-postcoloniale.html.

- Levi, Primo. 1988. The Drowned and the Saved. London: Vintage.

- Londres, Albert. 1924. Au Bagne. Paris: Albin Michel.

- Morin, Karen, and Dominique Moran. 2015. Historical Geographies of Prisons: Unlocking the Usable Carceral Past. London: Routledge.

- Nardizzi, Vin. 2013. “Greener.” In Prismatic Ecologies: Ecotheory Beyond Green, edited by Jeffrey Jerome Cohen, 147–169. Minneapolis: Minnesota University Press.

- Nixon, Rob. 2011. Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Nora, Pierre. 1984–1992. Les Lieux de mémoire. 3 vols. Paris: Gallimard.

- Nugent, Stephen. 1993. “From ‘Green Hell’ to ‘Green’ Hell: Amazonia and the Sustainability Thesis.” Occasional Paper No. 57, Amazonian Paper No. 3, Institute of Latin American Studies. University of Glasgow.

- Nugent, Stephen. 2007. Scoping the Amazon: Image, Icon, and Ethnography. Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press.

- Paterson, Lorraine M. 2018. “Ethnoscapes of Exile: Political Prisoners from Indochina in a Colonial Asian World.” International Review of Social History 63 (S26): 89–107.

- Piché, Justin, Kevin Walby, Jacqueline Z. Wilson, and Sarah Hodgkinson. 2017. The Palgrave Handbook of Prison Tourism. London: Palgrave.

- Pierre, Michel. 2017. Le Temps des bagnes. 1748–1953. Paris: Éditions Tallandier.

- Redfield, Peter. 2000. Space in the Tropics: From Convicts to Rockets in French Guiana. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Sanchez, Jean-Lucien, ed. 2010. Dominique Darbois, regard sur le bagne. La Seyne-sur-Mer: Maison du patrimoine et de l’image.

- Sanchez, Jean-Lucien. 2013. A Perpétuité: relégués au bagne de Guyane. Paris: Vendémiaire.

- Soares, Bruno Brulon, and Anna Leshchenko. 2018. “Museology in Colonial Contexts: A Сall for Decolonisation of Museum Theory.” ICOFOM Study Series 46: 61–79.

- Spieler, Miranda Frances. 2012. Empire and Underworld: Captivity in French Guiana. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Stoler, Ann Laura. 2013. “Introduction, ‘The Rot Remains’: From Ruins to Ruination.” In Imperial Debris: On Ruins, edited by Ann Laura Stoler, 1–35. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Stoler, Ann Laura. 2016. Duress: Imperial Durabilities in Our Times. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Suchet, André, and Michel Raspaud. 2011. “‘Le patrimoine, c’est un truc pour les vieux … ’ Le cas du rejet d’une politique de tourisme en faveur du patrimoine (vallée d’Abondance, Alpes du Nord).” Mondes du Tourisme 4: 49–60.

- Toth, Stephen. 2006. Beyond Papillon: The French Overseas Penal Colonies, 1854–1952. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- Welch, Michael. 2015. Escape to Prison: Penal Tourism and the Pull of Punishment. Oakland: University of California Press.