Abstract

This essay examines the history of the PAIGC radio station Rádio Libertação, broadcast from Conakry from 1967. The essay asks how to read the radio station today, and suggests we might see the radio station as a manifestation – albeit limited in scope and life span – of the commitment Amílcar Cabral sketched out in his theoretical writings to collapsing the dichotomy between the practical-utilitarian and the poetic-artistic. The essay reads the radio-magazine as a form that responded to the Portuguese colonial authorities’ information mania, but also as an heir to the journal cultures that sustained black internationalism in earlier decades. It takes the radio as a form in flux, emerging from and remediating the PAIGC’s print journal Libertação. The essay aims to show how the radio-magazine can help us understand the evolution of anticolonial debates about form, culture and society in the 1960s and 1970s.

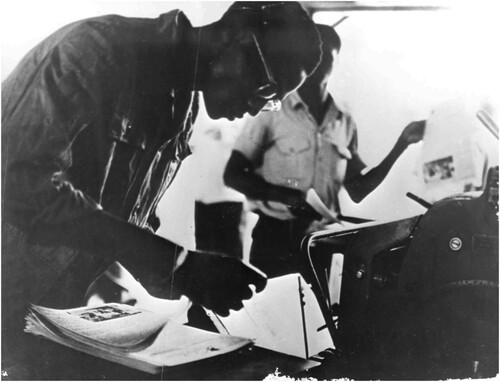

In Amílcar Cabral’s archive in Lisbon there is a black and white picture of a woman reading from a piece of paper and speaking into a microphone (). Amélia Araújo, photographed in 1967, was the main presenter on Rádio Libertação, broadcast from their Conakry base by the Partido Africano para a Independência da Guiné e Cabo Verde (African Party for the Independence of Guinea Bissau and Cape Verde, PAIGC). Further images show other subjects wearing shirts and glasses in the same style, also shot at work. One of them () shows a man typesetting the radio’s sister publication, the newspaper Libertaçāo. These and other striking portraits – presumably posed, or at least carefully composed – portray members of the PAIGC performing different kinds of textual, paratextual and sonic work: writing, typing, copying, printing, typesetting, broadcasting. What can those images tell us about cultural practice and changing ideas about text, language and culture in the plastic political contexts of the 1960s?

Figure 1 Amélia Araújo at the microphones of Rádio Libertação, broadcasting from Conakry, c.1967. Amílcar Cabral Archive, Fundação Mário Soares (10078.001.012).

Figure 2 Typesetting during the printing of the journal “Libertação”, c.1961-71, Documentos Amílcar Cabral, Fundação Mário Soares (05248.000.016).

In the decades since he was assassinated in Conakry in 1973, Cabral’s own writing about culture and liberation has received much critical attention (Andrade Citation1980; Dhada Citation1993; Jones Citation2020; Lopes Citation2013; Manji and Fletcher Citation2013; Mendy Citation2019). Alongside well-known texts by Césaire (Citation1956), Fanon (Citation1959a), and others, Cabral’s essays form part of the canon – if we can say such a thing exists – of anticolonial theorizing about culture. And yet, as the recent work of Borges (Citation2019) reminds us, the enduring valency of those anticolonial histories today extends beyond their perceived leaders and intellectual figureheads.

Recent scholarship on the PAIGC and Bissauan independence has already sought to “decentralize the emphasis so far exclusively laid upon the historical weight of Cabral as an individual” (Almada e Santos and Barros Citation2010, 9), better to understand what Borges calls the PAIGC’s “collective endeavour” (Citation2019, 19) of liberation, self-emancipation and transformation of consciousness. One appeal of these photographs, and the histories of Libertação – both radio and newspaper — to which they beckon, is that they repeople the terrain of anticolonial cultural praxis beyond Cabral’s writing, for all that he was a crucial collaborator in both projects. Our “biggest collaborator”, Araújo later said. In this essay I read the radio-magazine as a radical experiment in collective cultural production, and as a praxis that is itself a source of anticolonial ideas about culture. Formally speaking, I argue Rádio Libertação responded to and refracted the Portuguese colonial authorities’ information mania, and took up and took forward the juxtapositive logics of anticolonial journal cultures of earlier decades.

What is at stake in this argument? Unsympathetically put, the radio station was a short-lived, low-budget and sometimes didactic affair, often referred to in existing discussions with the militaristic cliché that it was the “mouth cannon”, the canhão da boca, of the PAIGC’s war effort (Lopes Citation2016). Certainly, Rádio Libertação was envisioned as an informative and useful tool. But it was a cultural intervention too: reading Rádio Libertação alongside Cabral’s writing and archive, I suggest we might see the radio station as a manifestation – albeit limited in scope and life span – of the commitment Cabral sketched out in his theoretical writings to collapsing the dichotomy between the practical-utilitarian and the poetic-artistic. It was a project informed by an ambition, in Kristin Ross’s terms, to transgress “perhaps the most time-honored and inflexible of barriers: the one separating those who carry out useful labor from those who ponder aesthetics” (Citation2008, 18). I propose here to see the station through the ambition it registers as a cultural experiment, even if that vision was not fully realized because of the material constraints it faced. To do so, I pay particular attention to the radio’s relationship of genealogy and counterpoint with the publication Libertação, and use the term “radio-magazine” both in the colloquial sense of describing a radio programme that covers a variety of topical items, as well as to capture the ongoing dialogic relationship between Libertação and Rádio Libertação.

Working on histories of what are often called “clandestine radios” – as Marissa Moorman (Citation2018, 244) and others have pointed out – is complicated by the fact that sound archives have often disappeared: sometimes lost, discarded, or recorded over; at other times damaged by heat or humidity. Beyond some scraps, this is the case with Rádio Libertação. These lost records demand that those of us who want to think about sonic histories rely on non-audible sources such as print records, photographs and censorship records: to approach one form through its registration in others. Here, I draw mainly on statements by the radio’s principal presenter, Amélia Araújo, on Cabral’s writing and on materials in his and the Portuguese state archives. This reliance on histories of text and image to access what was principally a sonic intervention necessarily curtails and determines our experience of engaging with that history today, as we cannot hear it. Nevertheless, given Rádio Libertação emerged as a remediation of a print publication, there is something appropriate – as well as necessarily curtailed – about a remediated critical approach to its history.

My argument builds on existing work in history and media studies on Rádio Libertação (Martinho Citation2017), on lusophone colonial and anticolonial broadcasting (Saide Citation2020; Moorman Citation2018, Citation2019; Ribeiro Citation2017) as well as broader work on clandestine and liberation radios in Africa (Gunner, Ligaga, and Moyo Citation2010; Scales Citation2013; Lekgoathi Citation2020, Citation2009; Kushner Citation1974; Heinze Citation2019, Citation2014). My engagement with the story of the radio station from a literary and cultural studies perspective, however, is centred on the claim that Rádio Libertação was an important intervention in the evolving rearticulations of the relationships between culture and politics that characterized the conjuncture of decolonization. This essay aims to show how the radio-magazine can help us understand the evolution of anticolonial debates about form, culture and society in the 1960s and 1970s.

Multilingual information

The PAIGC began broadcasting Rádio Libertação – Freedom Radio – from Conakry, the capital of Guinea (Pereira Citation2003, 333; Libertação 80, July 1967, 1), on 16 July 1967. The radio station had been long in the planning and the material technologies were put in place through internationalist support: Amélia Araújo was one of a group who attended a radio training placement in the USSR and returned with a mobile transmitter. Initially, the radio was run from a lorry in a form of mobile studio. Later, the station found a more fixed space and a more powerful emitter in downtown Conakry, in an area called La Minière, colloquially known as “Tricontinental” (Pereira Citation2003, 627) because of the steady stream of internationalist figures who passed through and stayed there. This detail – that “Freedom Radio” was disseminated from “Tricontinental” – neatly encapsulates the elision here between radio broadcasting with transnational networks of solidarity, and wider geographies of political solidarity.

Experimental broadcasts had begun in 1964. Rádio Libertação was directed at PAIGC militants across the country and overseas, broadcasting as far as they could and offering updates on the colonial war, information about party leaders, news and motivational speeches. Information provision was thus one of its key functions. It sought, as an article in Libertação put it, to “break the monopoly of information on the radio of the Portuguese colonialists” (80, July 1967, 2). As part of the colonial war, the PAIGC were engaged in a battle for information in which radio was a field of contestation. Cabral was attentive to the place and power of information in the struggle. He advised PAIGC cadres to “pay the closest attention to the question of information” (Citation1976, 235). Underlining the imbrications between knowledge and power, Cabral argued that, to win the colonial war, “we must constantly be gathering information” (Citation1976, 235). Cabral’s attention to the radio was sharpened by his practical experience organizing radio programmes at the Rádio Clube de Praia in Cape Verde the late 1940s (Chabal Citation1983, 44–45). We can see evidence of Cabral’s engagement with international radio in the letters he sent to radio stations whose coverage of the PAIGC he considered inaccurate. In 1962, for example, Cabral wrote to the directors of Radio Senegal and Radio Ghana to protest that the stations were spreading “lies and slander” that undermined “the reputation and the work of our party.”Footnote1 As such, Rádio Libertação aimed to keep party members in Guinea and Bissau up to date, but also to combat misinformation at an international level. As Cabral’s close comrade in Conakry, Mário Pinto de Andrade, argued, anticolonial movements had to break out of the “obscurantism” (Fele Citation1957) of Salazarist propaganda that isolated Portuguese African colonies on the world stage. For Andrade, the Salazar regime had suppressed so much information about the reality of life in its colonies that from the outside those countries appeared as “zones of silence” (Fele Citation1957). The radio project sought to unsilence those zones.

The form of the radio registered the conditions in which it emerged as a low-budget operation broadcasting in difficult circumstances and trying to evade detection. In 1967 they broadcast for fifteen minutes three times a day. As the years went on and the station’s technical capacity grew, the broadcasting became more ambitious: in 1971 the station was broadcasting one hour a day at 6.30 in the morning (“Students and the African liberation movement” 1971, 47) and a children’s programme for the pupils at the PAIGC school on Saturdays (Pereira Citation2003, 333). Araújo, the main presenter, characterized the evolution of the radio as a self-conscious and dialogic process:

We started with 15-minute broadcasts, three times a day and then, as we received information from different parts of Guinea confirming good reception, we increased the airtime to half an hour. As we gained experience, our programs improved. (Pereira Citation2003, 333)

Though I am drawing here on the testimony of one person, it is important to emphasize that the radio was a collective effort. It is hard to establish exactly how many other people were involved with the station apart from Araújo and her husband José, though in Cabral’s archive there is a 1967 memo listing members ordered to collaborate, including Otto Schacht, Domingos Brito, Armando Ramos, Emilio Costa, Carlota da Silva and Joaquim Landim (Ordem de Serviço 1967, 1). A note in Libertação also refers to a deceased militant, Eusébio Ribeiro, remembered for his early work in developing the radio (80, July 1967, 1). The collective nature of the radio project made possible its multilingualism. Rádio Libertação broadcast in Portuguese, but also in Creole, Balanta, Biafada, Mankanya and Manejo (80, July1967, 2). Araújo stated that linguistic standards at the radio were exacting: Cabral, for example, stopped her from broadcasting in Creole because she was not fluent enough (Pereira Citation2003, 335). Araújo emphasizes the collective multilingualism of the team:

Our team grew and ended up constituted by my husband and I, plus three more comrades, a Balanta, Zeca Martins, a Mankanya, Armando, and Malam, who was Biafada. Later Joaquim Landim appeared with Creole. They were all very young. Fula and Mandika came later as Sory Sow and Yaya Coté, respectively. There were also, of course, programmes in Portuguese: all the Party news, inside and outside Conakry, information about the struggles of the other Portuguese colonies and the War communications. All of this was later reproduced in the different languages of Guinea mentioned above, which were more widely spoken, and in Creole as well. (Pereira Citation2003, 333)

Nevertheless, the radio’s multilingualism was a significant dimension of this war of information. The Estado Novo, the Portuguese fascist dictatorship against whom the PAIGC were fighting, were obsessed with information: with collecting it, and, often, suppressing it. This is clear in the reams of censorship records, personal files and broadcast reviews that exist today in the Lisbon archives of the PIDE, the regime’s secret police. Information collection was a strategy of war but also a practice that inscribed a supremacist – in this case, fascist – desire to surveil, categorize, and control dissenters. Information provision for those struggling against this regime was, then, charged and shaped by that regime’s production of information about them. There are no records of Rádio Libertação in the PIDE archives, but there are notes responding to the Portuguese and Creole broadcasts the PAIGC put out over Radio Conakry earlier in the 1960s, addressed to listeners in Angola, Mozambique, Cabo Verde, Guinea, São Tomé and Senegal (Carvalho Citation1977, 97). These records provide tantalizing details about the tone of those broadcasts, recording the presenter announcing in the legible cadences of militant futurism, for example, that “the ice of colonialism is melting everywhere” (Note on Radio Conakry, 1960). Most remarkable, however, is the censor’s emphasis on how difficult it has been to monitor the radio broadcasts not in Portuguese. They cite interference with the signal, the difficulty of following the Creole, and that they are unsure of the quotations they have noted because of the “speed with which they are talking” (Note on Radio Conakry, 1960). Through these notes, multilingual broadcasting begins to come into view as a technology of information provision that danced around the censor, a form of possibility and communication that colonial authorities couldn’t dominate because they could not hear or understand it properly. In this sense, there are parallels to the oblique poetry Movimento Popular de Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola (People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola, MPLA) and PAIGC writers published in the 1950s, in journals such as Mensagem, that proved difficult for the censors to censor. Thinking across to other colonial contexts, Rebecca Scales’ observation that broadcasting in Algeria “challenged the classificatory mechanisms of the French colonial state” is also suggestive here (Citation2013, 305). The point here is that Libertação’s broadcasts took on a particular significance in the context of illiteracy in Guinea, as I will return to later, but also in relation to a certain form of colonial literacy. More specifically, underpinning the multilingual national community-in-the-making that Rádio Libertação broadcast was an understanding of community that rejected Estado Novo’s lusotropicalist ideas of a world harmoniously built on the Portuguese language. The PAIGC’s multilingualism fundamentally troubled the broader colonial “idealized alignment” (Harrison Citation2007, 341) between a single language and national identity.

These charged dynamics of language underline the entangled relationships between information and culture. The newspaper Libertação also disavowed an understanding of information as objective or neutral. In an article celebrating the anniversary of the radio station, it declared:

Beyond this purely informative work, our Radio has the great merit of being an instrument for the everyday politicization of the masses, for the mobilization of our people. Even more than that, it is an instrument of political work in the heart of the enemy, which has had its results, not only in the desertions that we have seen in the enemy’s ranks, but also, and above all, in the demoralization it has created there. (Libertação 92, July 1968, 1)

It is significant, too, that the article in Libertação emphasizes the enemy’s, not the militants’, heart. Rádio Libertação ran a regular programme addressed directly to Portuguese soldiers in Guinea, inviting them to see the injustice of the colonial war for which they were sacrificing lives, and appealing to the soldiers to see themselves, like the anticolonialists, as suffering from the absurd imperialist delusions of the fascist state. The radio station recorded interviews with soldiers who subsequently deserted:

There was a special programme exclusively dedicated to Portuguese soldiers. It was a programme that sought to make soldiers aware of the absurdity of that war and to mobilize them against this war they were waging without knowing why. As a result, there began to be many desertions. Indeed, many Portuguese soldiers deserted and those who were willing to be interviewed did so at Radio Libertação. This gesture had a tremendous impact on the others who stayed there. It demoralized them. (Pereira Citation2003, 334)

“A work of culture”

My proposition that this informational project should also be understood as a cultural and aesthetic gesture might seem counter-intuitive because of the distinction between literature, culture and aesthetics on the one hand versus information and utility on the other that underpins important thinking about the value of cultural work, including postcolonial cultural work. Here it is useful to go back to dominant ideas about culture and liberation amongst those resisting Portuguese imperialism. The PAIGC in Guinea-Bissau, FRELIMO in Mozambique and the MPLA in Angola worked closely together, including under the formalized auspices of the Conferência das Organizações Nacionalistas das Colónias Portuguesas (Conference of Nationalist Organizations of the Portuguese Colonies, CONCP), a co-ordinating organization that allied liberation fronts across the Portuguese empire during the colonial war. All insisted that culture was an important domain of contestation and liberation. However, they defined culture more widely than, for example, the poetry and written words that had been so important to black intellectuals in (especially) Paris and Lisbon in preceding decades.

Mário Pinto de Andrade, co-founder of the MPLA and later Cabral’s biographer, had worked between 1954 and 1958 at the Paris-based journal Présence Africaine, and was an important link between the black intellectualism of Paris journal-culture and the CONCP. Andrade emphasized Fanon’s place in the thinking of the lusophone anticolonialists, arguing: “political praxis is par excellence a work of culture. This was an idea of Fanon’s, which our group developed” (Laban Citation1997, 155; see also Andrade Citation1979, 8). Fanon had argued political struggle itself was the true cultural expression of a people in his speech at the 1959 second Congress of Black Writers and Artists in Rome organized by Présence Africaine: “the conscious and organized undertaking by a colonized people to re-establish the sovereignty of that nation constitutes the most complete and obvious cultural manifestation that exists” (Fanon Citation1959b, 95). Andrade, Cabral and other members of CONCP met Fanon in Rome at the conference. In particular, Cabral took up Fanon’s idea, writing in one of his central interventions on the topic – The role of culture in the independence struggle – that “the liberation struggle is, above all, an act of culture” (original emphasis) (Cabral Citation1976, 244). For Andrade and Cabral, then, culture was a central category, but the political expression of a people through political resistance was itself an expression of culture just as important as anything to be found on the page or on a canvas.

In these terms, we might say that if the struggle was a cultural act, Rádio Libertação was imagined, in largely indexical terms, to represent that act on the airways. But to go even further, the radio also went beyond representation: producing the radio was itself part of the struggle. It was a gesture of reclaiming cultural “initiative”, to use the word Aimé Césaire mobilized when he spoke at the same conference as Fanon in 1959 (127). In his 1959 Rome speech, Césaire argued that disrupting the colonial “hierarchy of creator and consumer” (original emphasis) was central to anticolonial cultural praxis (Citation1959, 127). In Césaire’s terms, then, the radio project was an act of cultural creation that converted “the colonized consumer into a creator” (original emphasis) (Citation1959, 127). Césaire’s work, Andrade noted, had in those early decades been like “oxygen” to the lusophone anticolonialists (Citation1979, 4).

Reaching “the masses”

Where Fanon’s work, based in his practice as a psychiatrist and in conversation with French philosophy, parses humanist ideas through studying the psychic subject; where Aimé Césaire’s work inscribes a poet’s faith in the transformative power of the creative individual; Cabral’s is the work of an agronomist and political organizer. He, unlike Césaire, was interested in what we might call the sociology of culture. Breadth of audience was important to him and his writing stresses the importance of achieving “a mass character, the popular character of the culture, which is not, and cannot be the prerogative of one or of certain sectors of the society” (Cabral Citation1974).

The breadth of its reach – both because of the cost of its production, and because of inaccess to education – was a limitation of print culture. Cabral pointed out that “in Angola, Mozambique and Guinea, 99 per cent of the population is illiterate” (Citation2004, 63), and that in Portugal illiteracy was also high: “50 per cent” (301). As students in Portugal in the 1950s, Cabral, Andrade and others, including the poets Noémia de Sousa and Alda do Espírito Santo, had run literacy classes (Laban Citation1997, 81). In 1953 they wrote an article for Présence Africaine highlighting the failings of the colonial education system and calling for the establishment of universities in the Portuguese colonies (Des Étudiants Citation1953). The article’s authors included Cabral, Andrade and Espírito Santo, as well as (future president of Angola) Agostinho Neto and the poet Francisco José Tenreiro, though given the already repressive political situation the article was anonymous, signed off Des Étudiants d’Afrique Portuguaise (“Some students from Portuguese Africa”). My point here is that Cabral, Andrade and the early groups in which they became politicized were conscious of the limits of print culture even as they participated in it. Looking back on this period in his later writing, Cabral described how “one part of the middle class minority engaged in the pre-independence movement, uses the foreign cultural norms, calling on literature … and precisely because he uses the language and speech of the minority colonial power, he only occasionally manages to influence the masses, generally illiterate and familiar with other forms of artistic expression” (Citation2004, 195).

The difficulties of disseminating print publications in Guinea is inscribed in the very pages of Libertação: “The Party cannot print a copy of Libertação for everyone. PASS THIS ON TO A COMRADE (89, April 1968, 4). In contrast to its own curtailed circulation, Libertação, the newspaper, anticipates Cabral’s lexicon of the multitudes in celebrating the value of the radio as a technology that allows the PAIGC “direct contact with the general mass of the population” (80, July 1967, 2). Of course, today, it is hard to establish to what extent this is a statement of achievement or intention. We do not have reliable information about radio ownership across Guinea or how Rádio Libertação touched “the masses”. Araújo’s own statements about how the radio was received are often speculative and vague. Her testimony emphasizes the lack of solid information those in the Conakry studio had about how far the signal reached and who was tuning in. Anecdotes like Malian university students remembering listening in provide details that testify to the radio’s international reach, though not to its successful shrugging off of a certain form of cultural elitism: “Amílcar Cabral so inspired our generation in Mali; we listened to the radio of the PAIGC, the radio of the liberation of Guinea-Bissau” (Manji and Fletcher Citation2013, 206).

Beyond the question of reach and breadth, a more nuanced question might be what new listening practices did Rádio Libertação engender. These are not fully retrievable. Marissa Moorman describes “scenes of secret or semi-secret listening” for audiences tuning into guerrilla radios in Angola (Citation2018, 251). Presumably, similar clandestine listening practices evolved around Rádio Libertação. One Portuguese soldier said he and his colleagues deployed in Guinea listened to Libertação’s programmes “on the sly” (às escondidas), unbeknownst to the officers at the base (Falam os portugueses prisioneiros de Guerra, 1968, 19). Some fragments, however, bring into view a sense of new public spaces of collective listening, at a perhaps smaller scale. Take this snapshot of a PAIGC militant, Teodora Gomes, listening to her radio, written by Stephanie Urdang, a South African writer and activist who spent time in Conakry with the PAIGC:

One of Teodora’s treasured possessions … was a small, black, scratched-up shortwave radio. It accompanied her everywhere. Each evening a group of cadres would cluster around to listen to the news from Lisbon … suddenly the clear voice of the Portuguese announcer cut through the evening air … when the newscast ended, everyone talked at once. Excitement competed with disbelief and loud voices argued each other down … Teodora’s radio continued to bring word from outside. (Urdang Citation2017, 148)

Broadcasting a “radio-magazine”

Nevertheless, the PAIGC idea, formalized by Cabral, of the liberation struggle as “act of culture” (original emphasis) (Citation1976, 244) helps us parse the cultural freight of both Libertação and Rádio Libertação. Unlike important long-running newspapers in Portugal’s African colonies and the literary journals in Lisbon and Paris with which Cabral and others associated with Libertação had been involved, Libertação was heavily news based, and did not publish poetry or self-consciously literary or fictional work, though articles about ‘cultural news’ in Guinea, especially about film and music making, were occasionally published. In this sense the newspaper seems to reflect the utilitarianism that inflects, for example, arguments by Andrade in the 1960s and 1970s that most forms of poetry had become superfluous aestheticizm in the midst of armed struggle. Yet to say that there is no “literary” writing on its pages is not to say that Libertação was not underpinned by forms of imaginative writing that sought to bring into being new visions of sociality and politics in Guinea-Bissau. The statements of militant zeal that Libertação published gesture to an imagined future the texts both reflect and seek to create. The articles were unattributed, which lent the publication a strong aura of party sponsorship; any imagined future was centrally endorsed. It was also mainly monolingual, published predominantly in Portuguese.

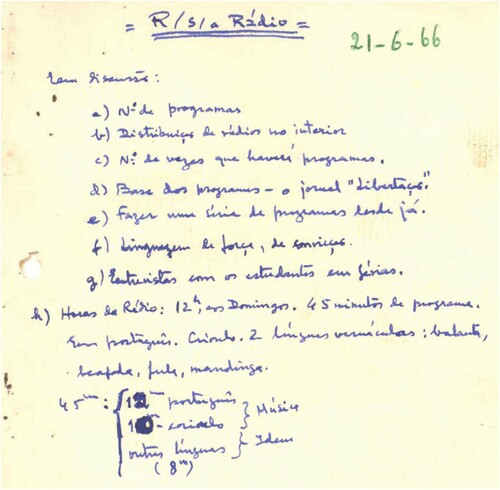

How did the newspaper change when, seven years after it was first published, it began to be broadcast? I am conscious here of Debra Rae Cohen’s warnings about recent work in literary radio studies, that, in privileging the radio text risk “paradoxically flattening broadcast into script, eliding the formal demands of the medium even as they argue for its centrality” (Citation2020, 335). It is important to be precise, therefore, about the relationship between newspaper and radio. First, and at a basic level, articles from Libertação were used as scripts for radio broadcasts. In a document in Cabral’s archive discussing the inception of the radio, we see clearly that the newspaper was intended as the basis for the radio programming (, point d). This genealogy allows us to understand the radio as an attempt to re-edit and re-transmit a written, print culture in a new context. Where Cabral and Andrade’s theoretical essays inscribe a palpable scepticizm about text and writing, however, the radio did not reject, but rather reamplified and remediated Libertação.

Figure 3 Meeting

notes: meeting about the PAIGC radio, 21 June 1966, Documentos Amílcar Cabral, Fundação Mário Soares (07072.124.019).

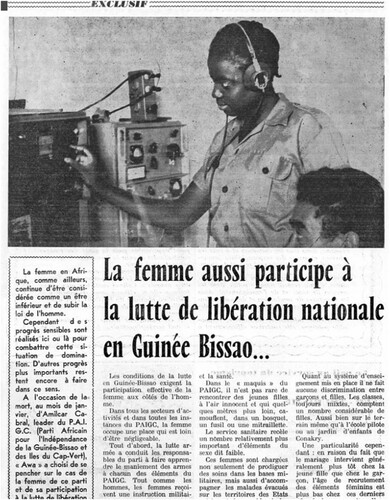

As time went on, what was originally a relationship of genealogy became a dialogic relationship: the newspaper also printed articles about the radio and describing its work (80, 1967). The two forms existed alongside, and in dialogue with, one another. It is reasonable to speculate that radio functioned more broadly as connective with print in this respect. In 1973, for example, the Senegalese women’s magazine AWA ran a feature on PAIGC women in Guinea and Guinea-Bissau. This feature emphasized women’s radio work as an important contribution to the freedom struggle (). The radio, here, functions as a technology that allowed PAIGC women to become legible as part of a transnational network disrupting gendered divisions of labour in anticolonial movements. Key figures of AWA’s editorial board, including Annette M'Baye d'Erneville and Henriette Bathily, also worked on the radio. As Tsitsi Jaji’s work has shown, print magazines such as the Senegalese Bingo advertised radio to women (Jaji Citation2014, 142–146). The vignette of Teodora Gomes also offers a glimpse of how the radio allowed women to connect to broader militant networks outside the domestic. Radio-work became part of a print culture of imagining what women’s work outside the bourgeois-domestic could be.Footnote2

Figure 4 “Women participate in the national liberation struggle in Guinea-Bissau”, Awa Magazine, May. 1973, p.6 (right). (Founded by Annette Mbaye d’Erneville en 1964, this review has been digitized by the IFAN-Cheikh Anta Diop as part of a project between the universities of Bristol and Paul-Valéry – Montpellier 3, in partnership with the IFAN-CAD, the National Archives of Senegal and the Musée de la femme Henriette-Bathily).

The transposition of Libertação to Rádio Libertação in 1967, of course, changed it. The shift from newspaper passed hand to hand might have achieved greater breadth of audience, and might have reached audiences in a wider array of languages, but also came with its own limits. In particular, programmes broadcast into a sonic space filled with competing radio broadcastsFootnote3 made the effect of Libertação less legible to those who produced it. A voice across a crackling radio comes with less paratextual orientation than a newspaper, though this might have made it easier to access for those for whom to do so was dangerous.

One significant change was that the radio broadcast music in different languages, creating a space for oral and polyglot forms of culture that could appeal to a wider audience in Guinea. Libertação, the newspaper, hailed these songs as “full of beauty, optimism and vigour” (64, March 1966, 4). More broadly, the station also began to function as a repository of Guinean music culture, recording the songs and music of militants who came to Conakry from across the country:

We recorded music from all, or almost all, ethnic groups, with the combatants themselves or with people from the liberated regions. When they came to Conakry to get supplies and weapons, we used the opportunity to gather a group together and record … For me, this has an extraordinary value, as Guinean culture, which was stifled until then, began to be disseminated … I imagine the pleasure with which the population … listened to their songs … The impact was great in their hearts. (Pereira Citation2003, 333–334)

Some of these songs remain available today as they were compiled on the record Uma cartucheira cheia de canções (A Cartridge of Songs), a title that reproduces the militaristic imaginary of the radio as “the mouth canon”.Footnote4 The tone of these songs is highly partizan, affirmative and forward looking, rather than traditionalist or nostalgic. These songs capture a society in motion: local music styles redeployed in the service of the liberation struggle. Some are party songs. The Balanta song by Sia Caby, Unity and Struggle, and the Fula song by the musician Aliu, Viva PAIGC, sing about the PAIGC in celebratory terms. Some take a more laconic tone: “Feeling for the tugasFootnote5 in Guinea” by the Creole composer José Lopes notes: “Your commandos are crying, because of our land!” Others, also nationalist in tone, are satirical. One, titled “They who have land”, by the Balanta musician N’Fôre Sambú, deploys the form of call and response to create a sense of collective voice:

In 1979 Mário Pinto de Andrade included some of the Rádio Libertação songs in the two-volume poetry anthology he published that presented the evolution of twentieth-century Portuguese-language African poetry from early poems published in the Cape Verdean journal Claridade in the 1930s, the Mozambican O Brado Africano in the 1940s, through the poems published by Andrade, Cabral and their colleagues in the Lisbon journal Mensagem in the 1950s and beyond. In his preface to the second volume, O canto armado (The Armed Song), written in Bissau in November 1978, Andrade hails this new poetry’s ability to communicate “Confidence in the party, certainty of liberation, victory of the power of weapons” (original emphasis) (Citation1979, 9). Where, during the “colonial night”, (8) poetry had been marked by “an allusive character,” (8) the revolutionary songs of the armed struggle were characterized by their “clear and direct language” (8). For all its appealing celebration of popular creativity, Andrade’s defence of this poetry in terms of its clarity has always struck me as unconvincing. It takes a neorealist’s faith in the referential function of language so far that he suggests poetry can play an almost causal role in ensuring people arrive at a prescribed political position.

Thinking about Rádio Libertação as a form that picked up, stretched and remediated the earlier journal cultures that are so central to Andrade’s genealogy of African poetry in Portuguese allows us to understand the cultural praxis of the armed struggle in different terms. In different ways, part of the critical charge of O Brado Africano, Présence Africaine and Mensagem lay in their juxtapositive logics. They juxtaposed “the literary” and non-literary writing, conjugating “the literary” and “the cultural” with other parts of social life and, in so doing, disrupted the calcified colonial classifications that separated parts of the social whole. In Présence Africaine’s terms, “we find the essential characteristic of colonialism in the deliberate separation of the two concepts (politics and culture)” (“Le Combat Continue”, Citation1960, 5).

In this respect, these journals were quite different to the anglophone “postcolonial little magazines” such as Black Orpheus, which included no commentary on news, current affairs or state policies. In fact, Peter Kalliney and others’ work has demonstrated that Ulli Beier’s publication was “fastidiously apolitical” (Citation2015, 354) partly because of the constraints of the funding it received from the Congress for Cultural Freedom, a CIA front. Nevertheless, there is an obvious difference in emphasis here, all the more remarkable given that Black Orpheus declared itself to be continuing the “excellent work” of Présence Africaine (Jahn Citation1957, 40).

That is, part of the critical charge of journals like Présence Africaine – which Andrade, Cabral and others wrote for and passed around “on the sly” as students in Lisbon – was formal. Libertação, the newspaper, did not achieve this juxtapositive form in the context of the marginality of print to popular cultures in Guinea. The radio, meanwhile, did. Drawing on different languages and bringing together news and song, it took up and took forward that tradition of anticolonial work rearticulating a changing relationship between politics, culture and language, a rearticulation which we see not so much in individual texts it published and broadcast as much as in its form. The radio-magazine stretched and repurposed the journal form in a new context to create a magazine – multilingual variety broadcasts with music, analysis and news– for readers who couldn’t read. As I argued earlier, we see in the censorship records how these broadcasts, in their own way, troubled the “classificatory mechanisms” (Scales Citation2013, 305) of the colonial state.

Existing work on radio in literary postcolonial studies has powerfully argued for the connections between literary modernism and broadcast infrastructure, focusing on, in particular, the imbrications between institutions such as Dennis Duerden’s Transcription Centre, the French Overseas Radio Service’s Concours Théatral Interafricain and BBC programmes such as Caribbean Voices, Calling West Africa and Calling the West Indies, that broadcast African and Caribbean writers working in English and French (Breiner Citation2003; Kalliney Citation2013; Cyzewski Citation2018; Conteh-Morgan Citation1991; Ricard Citation1973; Moore Citation2002; Cohen, Coyle, and Lewty Citation2009; Smith Citation2018; Gunner Citation2019). This work has allowed us to see more clearly the imbrications of literary creativity and radio infrastructures that a narrower focus on text only obscures. The project of Rádio Libertação was of a different scale to the radio infrastructures of national broadcasters like the BBC, and posited its own ideas about what kind of work was culturally significant. Nevertheless, this body of scholarship speaks to my own argument that Rádio Libertação brings into view an expanded field of cultural practice, articulated to a print cultural world but that also moved beyond it.

Conclusion

Underpinning this essay is the question of how important conversations about culture that took place in anticolonial print cultures in the earlier conjuncture of decolonization lived on and changed shape and in the plastic political contexts of the late 1960s and 1970s. In beginning to answer that question, I have argued Rádio Libertação adapted and stretched the print heritage from which it emerged, forging a multiformal radio-magazine for new audiences in new places. The radio-magazine developed new sonic and linguistic coordinates to record and take forward the PAIGC’s struggle for freedom in Guinea. As a collective praxis, the radio project inscribes the PAIGC’s changing ideas about language, text, culture and society in the anticolonial 1960s and 1970s. Libertação was born of a need to contest colonial fictions of information in the radiophonic field, but also of a conviction that the struggle for land, power, sovereignty and changed social relations was inseparably entangled with a struggle for aesthetics, language and new cultural forms in motion.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 See also Cabral’s letter to the director of Rádio Ghana (1962).

2 See also the profiles of radio-women: “Khady Kane” in AWA (Citation1964), and “Mme Mbaye d’Erneville” in Amina (1975).

3 The timetables from Radio Peking and Radio Berlin in Cabral’s archive remind us of the international radio networks that crossed imperial language lines, as both broadcast in French to West Africa. (Radio Pequim, c.1961; Rádio Berlin Internacional [n.d.]). Radio Moscow did a daily Portuguese broadcast (Oliveira Citation1996).

4 My translations here are based on translations from the Portuguese and French lyrics included in the dust jacket of the record.

5 Portuguese colonialists

6 A Guinean river fish.

References

- Africaine, Présence. 1960. “Le Combat Continue.” Présence Africaine 31: 3–7.

- Allan, Michael. 2019. “Old Media/New Futures: Revolutionary Reverberations of Fanon’s Radio.” PMLA 134 (1): 188–193. doi:https://doi.org/10.1632/pmla.2019.134.1.188.

- Andrade, M. de. 1979. Antologia Temática de Poesia Africana, Vol. 2: O Canto Armado. Lisbon: Sá da Costa.

- Andrade, M. de. 1980. Amilcar Cabral: Essai de Biographie Politique. Paris: F. Maspero.

- Borges, Sónia Vaz. 2019. Militant Education, Liberation Struggle, Consciousness: The PAIGC Education in Guinea Bissau 1963–1978. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

- Breiner, Laurence A. 2003. “Caribbean Voices on the Air: Radio, Poetry, and Nationalism in the Anglophone Caribbean.” In Communities of the Air: Radio Century, Radio Culture, edited by Susan Merrill Squier, 93–108. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Cabral, Amilcar. 1974. “National Liberation and Culture.” Transition 45: 12–17.

- Cabral, Amilcar. 1976. Unidade e Luta. 1, a Arma da Teoria. Lisbon: Seara Nova.

- Cabral, Amilcar. 2004. Unity and Struggle. Translated by Michael Wolfers and Edited by Mauruce Taonezvi Vambe and Abebe Zegeye. Pretoria: Unisa Press.

- Cabral, Amilcar. 2016. Resistance and Decolonization, edited by D. Wood, and R. Rabaka. London: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Carvalho, O. 1977. Alvorada em Abril. 2nd edn. Lisbon: Bertrand.

- Césaire, Aimé. 1956. “Culture et Colonisation.” Présence Africaine 8–9–10: 190–205.

- Césaire, Aimé. 1959. “The man of Culture and his Responsibilities.” Présence Africaine 24–25: 125–132.

- Chabal, Patrick. 1983. Amílcar Cabral: Revolutionary Leadership and People’s War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Cohen, D. R., M. Coyle, and J. Lewty. 2009. Broadcasting Modernism. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

- Cohen, Debra Rae. 2020. “Wireless Imaginations.” In Sound and Literature, edited by Anna Snaith, 334–350. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Conteh-Morgan, John. 1991. Theatre and Drama in Francophone Africa: A Critical Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Cyzewski, Julie. 2018. “Broadcasting Nature Poetry: Una Marson and the BBC’s Overseas Service.” PMLA 133 (3): 575–593.

- Des Étudiants, d’Afrique Portuguaise. 1953. “Situation des étudiants Noirs Dans le Monde.” Présence Africaine 14: 221–240.

- Dhada, Mustafah. 1993. Warriors at Work: How Guinea Was Really Set Free. Boulder: University of Colorado Press.

- e Santos, Aurora Almada, and Víctor Barros. 2010. “Amílcar Cabral and the Idea of Anticolonial Revolution.” Lusotopie 19 (1): 9–25. doi:https://doi.org/10.1163/17683084–12341746.

- Fanon, Frantz. 1959a. L’an V de la Révolution Algérienne. Paris: Maspero.

- Fanon, Frantz. 1959b. “The Reciprocal Basis of National Cultures and the Struggles for Liberation.” Présence Africaine 24–25: 89–97.

- Fanon, Frantz. 1965. “This is the Voice of Algeria.” In A Dying Colonialism, edited by Haakon Chevalier, Chap. 2, 69–97. New York: Grove Press.

- Fele, Buanga [Mário Pinto de Andrade]. 1957. “Ghana et les Zones de Silence en Afrique Noire.” Présence Africaine 12: 71–72.

- Gunner, Elizabeth. 2019. Radio Soundings: South Africa and the Black Modern. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gunner, Elizabeth, Dina Ligaga, and Dumisani Moyo. 2010. Radio in Africa: Publics, Cultures, Communities. Johannesburg: Wits University Press.

- Harrison, Nicholas. 2007. “Review Essay: Life on the Second Floor.” Comparative Literature 59 (4): 332–348. doi:https://doi.org/10.1215/-59–4–332.

- Heinze, Robert. 2014. “‘It Recharged our Batteries’: Writing the History of the Voice of Namibia.” Journal of Namibian Studies 15: 25–62.

- Heinze, Robert. 2019. “Dialogue Between Absentees? Liberation Radio Engages Its Audiences, Namibia, 1978–1989.” Participants 16 (2): 489–510.

- Jahn, Janheinz. 1957. “World Congress of Black Writers.” Black Orpheus: A Journal of African and Afro-American Literature 1: 39–46.

- Jaji, Tsitsi. 2014. Africa in Stereo: Modernism, Music, and Pan-African Solidarity. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Jones, Branwen Gruffydd. 2020. “Race, Culture and Liberation: African Anticolonial Thought and Practice in the Time of Decolonisation.” International History Review 42 (6): 1238–1256.

- Kalliney, Peter J. 2013. Commonwealth of Letters: British Literary Culture and the Emergence of Postcolonial Aesthetics. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Kalliney, Peter J. 2015. “Modernism, African Literature and the Cold War.” Modern Language Quarterly 76 (3): 333–368.

- “Khady Kane: Opératrice de Radiodiffusion.” 1964. AWA 7: 14–15.

- Kushner, James M. 1974. “African Liberation Broadcasting.” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 18 (3): 299–310. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/08838157409363744.

- Laban, Michel. 1997. Mário Pinto de Andrade: uma Entrevista Dada a Michel Laban. Lisbon: Sá da Costa.

- Lekgoathi, Sekibakiba Peter. 2009. “‘You are Listening to Radio Lebowa of the South African Broadcasting Corporation’: Vernacular Radio, Bantustan Identity and Listenership, 1960–1994.” Journal of Southern African Studies 35 (3): 575–594.

- Lekgoathi, Sekibakiba Peter. 2020. Guerrilla Radios in Southern Africa: Broadcasters, Technology, Propaganda Wars, and the Armed Struggle. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Lopes, Ângelo. 2016. Canhão de Boca. Luanda: O2.

- Lopes, Carlos. 2013. Africa’s Contemporary Challenges: The Legacy of Amilcar Cabral. London: Routledge.

- Manji, F., and B. Fletcher. 2013. Claim No Easy Victories: The Legacy of Amilcar Cabral. CODESRIA.

- Martinho, Teresa Duarte, et al. 2017. “Amílcar Cabral, the PAIGC and the Media: The Struggle in Words, Sounds and Images.” In Media and the Portuguese Empire, edited by José Luís Garcia, 291–307. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mendy, Peter Michael Karibe. 2019. Amilcar Cabral: A Nationalist and Pan-Africanist Revolutionary. Athens: Ohio University Press.

- Moore, Gerald. 2002. “The Transcription Centre in the Sixties: Navigating in Narrow Seas.” Research in African Literatures 33 (3): 167–181.

- Moorman, Marissa. 2018. “Guerrilla Broadcasters and the Unnerved Colonial State in Angola (1961–74).” Journal of African History 59 (2): 241–261. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021853718000452.

- Moorman, Marissa. 2019. Powerful Frequencies: Radio, State Power, and the Cold War in Angola, 1931–2002. Athens: Ohio University Press.

- Nafafé, J. 2013. “Flora Gomes’s Postcolonial Engagement and Redefinition of Amílcar Cabral’s Politics of National Culture in Nha Fala.” Hispanic Research Journal 14 (1): 33–48.

- Oliveira, César. 1996. “Rádios Clandestinas.” In Dicionário De História Do Estado Novo, edited by Fernando Rosas, and José Maria Brandão De Brito, 811. Venda Nova: Bertrand Editora.

- Pereira, Aristides. 2003. O meu Testemunho: uma Luta, um Partido, Dois Países. Lisbon: Notícias.

- Pereira, Carmen Maria de Araújo. 2016. Os Meus Três Amores: o Diário de Carmen Maria de Araújo Pereira: uma Visão de Odete Costa Semedo. Bissau: Instituto nacional de estudos e pesquisa.

- Ribeiro, Nelson, et al. 2017. “Colonization Through Broadcasting: Rádio Clube de Moçambique and the Promotion of Portuguese Colonial Policy, 1932–64.” In Media and the Portuguese Empire, edited by José Luís Garcia, 179–195. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ricard, Alain. 1973. “The ORTF and African Literature.” Research in African Literatures 4: 189–191.

- Ross, Kristin. 2008. The Emergence of Social Space: Rimbaud and the Paris Commune. London: Verso.

- Saide, Alda Romao Saute, et al. 2020. “A Voz da Frelimo and the Liberation of Mozambique.” In Guerrilla Radios in Southern Africa: Broadcasters, Technology, Propaganda Wars, and the Armed Struggle, edited by Sekibakiba Peter Lekgoathi, 19–39. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Scales, Rebecca. 2013. “Métissage on the Airwaves: Toward a Cultural History of Broadcasting in French Colonial Algeria, 1930–1936.” Media History 19 (3): 305–321. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13688804.2013.817837.

- Smith, Victoria Ellen. 2018. Voices of Ghana: Literary Contributions to the Ghana Broadcasting System 1955–57. Woodbridge: James Currey.

- Tomás, António. 2008. O Fazedor de Utopias: uma Biografia de Amílcar Cabral. Praia: Spleen Edições.

- Urdang, Stephanie. 2017. Mapping My Way Home: Activism, Nostalgia, and the Downfall of Apartheid South Africa. New York: Monthly Review Press.

- Archival Sources.

- Amílcar Cabral archives, Fundação Mário Soares (Lisbon).

- Arquivo Mikko Pyhälä Archive, Fundação Mário Soares (Lisbon).

- Mário Pinto de Andrade Archive, Fundação Mário Soares (Lisbon).

- PIDE archive, Portuguese National Archives, Torre do Tombo (Lisbon).

- Amílcar Cabral Archives.

- Libertação, Órgão do Partido Africano da Independência (Guiné e Cabo Verde). 1960–71 (07177).

- Cabral, Amílcar. 1962. “Letter to the director of Rádio Ghana” (04617.080.062).

- Cabral, Amílcar. 1962. “Letter to the director of Rádio-Senegal” (04612.064.019).

- “Reunião sobre a Rádio e a Informação.”.16 December 1970 (07072.124.026).

- “Ordem de Serviço.”.19 June 1967 (04606.045.126).

- “Rádio Berlim Internacional.” [n.d.] (04617.081.007).

- “Rádio Pequim.” c.1961 (04608.053.067).

- Arquivo Mikko Pyhälä.

- “Students and the African Liberation Movement.” 14–18 February 1971 (11025.00).

- Arquivo Mário Pinto de Andrade.

- “Falam os portugueses prisioneiros de Guerra.” August 1968 (04309.007.011).

- PIDE Archive.

- Note on Radio Conakry (PT/TT/AOS/D-N/25/14/8).