Abstract

Since the 1980s, a growing body of scholarship suggests that societal concerns and management of risk have become a central feature of modernising societies. Most prominently Ulrich Beck has asserted that modern societies were increasingly confronted with the side-effects of social progress challenging the modern machinery, such as science and insurance, to manage risk. Since this early focus on technological advancement and environmental degeneration, there have been little systematic empirical analyses of the forces that drove the proliferation of risk in the public sphere. Following suggestions by Luhmann, among others, that the risk semantic is central to modernisation and Skolbekken’s description that since 1945 medical journals have experienced a ‘risk epidemic’, this article examines the developments and events responsible for the social proliferation of health risk. In particular, I utilise The Times corpus (1790–2009) provided by the Corpus Approaches to Social Sciences research centre at Lancaster University, and the corpus linguistics tool CQPweb, for a detailed quantitative and qualitative analysis of language in its social contexts. I argue that the occurrence and increasingly widespread use of the ‘at risk’-expression indicate a transformation of public consciousness related to a growing social prominence of health and well-being, the normalisation of rational management of health, and the definition of social reality by its ‘at risk’-status.

Introduction

Since the 1980s, a growing body of scholarship suggests that societal concerns and management of risk have become a central feature of modernising societies (see, for example, Beck, Citation1992; Citation2009; Douglas & Wildavsky, Citation1982; Giddens, Citation1991). However, theorising of this shift towards risk has encountered difficulties in substantiating these claims with empirical evidence and related insights into the reasons for this long-term social change (Crichton et al., Citation2016). In this article, I aim to provide such evidence by the analysis of the articles published in a central media outlet, The Times (1785–2009), which I argue reflect and have shaped the public debate over decades. The analysis builds on the assumption that language is central to the social construction of reality (Berger & Luckman, Citation1966) and therefore a good way of generating evidence for social change. For this purpose, I conducted a study which utilised corpus linguistics tools to identify the meaning of an increasingly frequent expression – ‘at risk’ – and the possible reasons for its spread. In this article, I focus on the health domain since a number of studies have found health to be central to the proliferation of risk language (see Hardy & Colombini, Citation2011; Zinn & McDonald, Citation2018). However, understanding linguistic changes requires a detailed analysis of both the social contexts and the changes in media production (Conboy, Citation2010; Curran & Seaton, Citation2018). Therefore, in the article, I examine key (institutional) developments and events, which have contributed to the introduction and increasingly frequent use of ‘at risk’ expressions. I also consider changes in the production of news as well as in society more broadly.

Researching the shift towards risk

Since the 1980s, a number of social theorists tried to explain increasing public debates about risk. Mary Douglas and Aaron Wildavsky in Risk and Culture (Citation1982) made socio-cultural shifts responsible for a growing opposition against nuclear power. Ulrich Beck, in his work on the Risk Society (Beck, Citation1992; Citation2009), suggested that ongoing modernisation dynamics produce side-effects such as new catastrophic risks, which push societies into a new stage of modernisation characterised by heightened conflicts about risk. Scholars developing Michel Foucault’s work on power have positioned risk in the context of a new form of governing populations, called governmentality, which would utilise risk technologies and neoliberal ideologies (Dean, Citation1999). However, even though all these approaches are strong in highlighting particular dimensions considered central to the societal shift towards risk, their macro-theoretical considerations, on the basis of general scholarly observations and fine grain historical case studies, have provided a ‘mixed bag’ of evidence to explain the proliferation of risk language in the public sphere.

One reason for their limited explanatory power might be that the role of the media remains under-theorised. Even when the media’s shaping of social awareness is addressed, as in the work of Ulrich Beck, it is not theorised thoroughly enough (Allan et al., Citation2000; Beck, Citation2000; Huan, Citation2016) to clarify the media’s contribution to the shift towards risk. This is surprising since the print news media had been celebrated as a central social institution constituting an important part of the public sphere (Starr, Citation2004) while reporting on disasters was the staple of news (Jones, Citation1976). Indeed, many of the risks we know only about since they are reported in the media. However, the news media’s form and content change over time in competition with other media. With the trend towards mass production, newspapers were increasingly dependent on advertisers and new audiences and therefore shifted style, content, and layout to attract both readers and advertisers (Conboy, Citation2010, pp. 137–8). Conboy suggested that with broadcasting, newspapers lost being the fastest source for news and concentrated on the development of particular ‘voices’ through a focus on commentary and opinion (Conboy, Citation2002, pp. 114–126).

At the time there were trends to write for the expanding public-sector professions (education, social services, for example) and to use additional revenue from advertising for extra pagination to expand sections for analysis and commentary. In particular, the elite press targeted increasingly affluent and socially engaged professional women readers, which came with a trend towards specialist columns, idiosyncratic opinion, and commentary (Conboy, Citation2010: 141–2; Jucker & Berger, Citation2014; Fink & Schudson, Citation2014; Duguid, Citation2010). The output of news media has always been contested and shaped by social forces and the economics of media production (Curran & Seaton, Citation2018). In this sense, journalists do not merely report and comment on what happens but reflect the social organisation of a society, as it is characterised by divisions such as between the rich and the poor, men and women, and white people and people of colour, which shape language and content of the news. Understanding the shift towards risk must, therefore, be complemented by examining how the different forces populating the public sphere have shaped the communication of risk. As has been argued for a long time, this is not merely about what the media reports upon but how – thus giving language and discourse a prominent role in the production, reproduction, and change of the social sphere (Berger & Luckman, Citation1966; Fairclough, Citation1995; Wodak & Meyer, Citation2015).

Most scholars agree that there is a close connection between the occurrence and spread of the risk semantic and the modernisation process, which has been characterised by Max Weber as a process of rationalisation during which the future became accessible to human planning (Weber, Citation1948). Thus, responsibility for the future shifts from God or supernatural forces to humanity. This change was not merely a shift of worldview but was accompanied by the development of new evidence-based forms of knowledge (science), the development of institutions (such as universities), as well as techniques and practices (statistics, insurance) to manage risk and uncertainty (Bernstein, Citation1996; Hacking, Citation1990). Indeed, even though risk studies have focussed on the sphere of economics and how maritime trading fostered the development of risk management strategies such as early forms of insurance (Giddens, Citation2000; Luhmann, Citation1993), functionally differentiating societies witnessed modernisation processes and a rise of the risk semantic in politics (Franklin, Citation1998) and medicine as well (Green, Citation1997). A diachronic study on discourse and language in the news should therefore allow us to identify and trace significant social changes including changes in the social understanding and responses to health and illness.

Despite huge advances in medical knowledge, from Antiquity to the present day – from advances in the understanding of the functioning of the human body, to the causes of illnesses such as viruses and bacteria, to the discovery of antibiotics and the development of vaccines – it is only recently that risk language has proliferated within medical science journals. Based on his analysis of American, British, and Scandinavian medical science journals from 1967 to 1991, John-Arne Skolbekken (Citation1995) suggested that a ‘risk epidemic’ has taken place, which was particularly pronounced but not restricted to epidemiology journals. While epidemiology witnessed significant developments after World War Two, the development of computers, which allowed researchers to conduct more complex calculations and to process a large body of data, helped to identify a growing number of risk factors responsible for the development of illnesses.

These shifts were paralleled with a shift in focus in public health from accidents to prevention, relying on the identification of various risk factors (Green, Citation1999). Institutionally, this was accompanied by the development of risk management and risk analysis and the growing prominence of quality assurance in health services and health education which, according to Skolbekken, are likely to have contributed to the ‘epidemic’ of risk words in medical science journals. Skolbekken admitted however that the concept of ‘risk’ he found in medical science journals is far from coherent, confirming insights from risk studies more generally. There is a variety of different understandings of risk in the sciences and social sciences (Renn, Citation1992) as well as in the public sphere (Crichton et al., Citation2016), and this should be taken into account in any risk study, as outlined below.

Research design, methodology and methods

There is considerable debate regarding what ‘risk’ is, how it should be defined (e.g., Althaus, Citation2005; Renn, Citation1992), and who has the authority to define it (experts or the public, for example, see Rosa, Citation2010). Since agreement remains unlikely, it seems more appropriate for the analysis of broader societal change to keep the use and understanding of ‘risk’ open for analysis. The occurrence and increase of risk wordsFootnote1 can serve as a starting point for exploring the social changes which triggered the development of new linguistic expressions and their diffusion (similarly: Koselleck, Citation1989; Luhmann, Citation1993).

In this study, I followed earlier research which has argued that risk words are a reasonable proxy-variable for the risk semantic (see Zinn & McDonald, Citation2018). Although there are all kinds of words which might have some overlapping with the meaning of risk, such as danger, threat, and peril, there is good evidence that the meaning of these expressions differs (Battistelli & Galantino, Citation2019; Boholm, Citation2012). Indeed, risk words have been used in the news media throughout the 19th and 20th century and occurred in a wide range of expressions. However, there is a clear shift observable that started with the 1960s and 1970s, a time during which ‘at’ most regularly co-occurs with ‘risk’, while the at risk expression occupied a growing proportion of the semantic space (Zinn, Citation2020: 67ff.). To explore these changes, this article uses a case study of The Times. The focus is on health issues since health and illness form the dominant thematic domain in which at risk is instantiated (Zinn & McDonald, Citation2018: 137ff.) and seem to be a driving force fostering the proliferation of risk.

My analysis is based on a unique resource, The Times corpus, made available through Lancaster University’s CQPweb server.Footnote2 The pre-processed corpus provides all articles published from 1785 to 2009 and allowed me to analyse a huge number of instantiations of risk words against the backdrop of all articles, in contrast to most analysis which can only rely on comparatively small, thematically focused corpora. My approach also enabled detailed analysis of discourse-semantic changes over a long-time span otherwise not possible. Despite The Times representing a rather conservative middle-class perspective of the world, it reflects to a large degree the language and the social debates which were being debated and examined at a point in time, allowing a meaningful analysis of historical social change. Nerlich et al. (Citation2012) similarly based their comparison of UK and US climate discourse on one newspaper per country (The Times and the New York Times).Footnote3

Because of the huge amount of data, the corpus has been divided into 23 subcorpora, each containing all articles from one decade from 1790 to 1799 and so on until 2000 to 2009 with the exception of the 1780s that only consists of the years 1785 to 1789 (compare for more detail of the technical aspects: Zinn, Citation2020, pp. 59–71). Altogether, the corpus consists of 6,803,359,769 words, which include 429,831 risk words and 40,541 instances of ‘at risk’.

Since the data are based on automatised OCR recognition of The Times archive, older texts contain a large number of mistakes that would affect the quality of fine-grain analysis of the earliest volumes. It is likely that the numbers of occurrences of specific word patterns in the earlier decades of the 19th century are systematically underestimated. However, since the corpus is very large it is unlikely that these issues affect the analysis to a large degree (Joulain-Jay, Citation2017) and the thematic analysis might be less affected where it refers to the general thematic context rather than to specific linguistic expressions.

In the research, I combine corpus linguistic tools (Zinn, Citation2019) with the analysis of social contexts to gain insights about the (social) forces, which drive the occurrence and change of the risk semantic in print news media. In contrast to quantitative content analysis, corpus linguistics provides a number of tools and pre-processing, which allows more targeted and detailed analysis. For example, it is possible to search for the lemma (for the verb ‘to risk’ this includes also other verb forms such as ‘risking’, ‘risked’, ‘risks’) and it also allows me to distinguish between the verb ‘risk’ and the noun ‘risk’.

My analysis is based on the insight that the meaning of a word results from the company it keeps (Firth, Citation1957, p. 179) or – in other words – the words co-occurring with it. The likelihood that a word such as ‘at’ occurs close to ‘risk’ can be statistically measured (Evert, Citation2009). For such collocations, different statistical measures are available such as Mutual Information (MI) and Dice Coefficient, which produce many low-frequency-collocates populating the top ranks in a collocation list (Baker, Citation2006: 101ff.). This means that words which rarely occur in a corpus are high in the list because they almost always appear together with the node (in the case of this study ‘at risk’). Since the following analyses are more interested in the most frequent words and how their occurrence changes over time, the log-likelihood (LL) has been used, which is more sensitive to high occurrence words (Baker, Citation2006, p. 102). The following analysis uses statistical collocations mainly to inform and direct detailed qualitative analyses. Using so-called concordance lines, which display as many words before and after the node as desired, helped me to specify the wider context of the articles and to reconstruct the meaning of at risk and its conditions of occurrence (see Zinn, Citation2020 for a detailed overview).

Findings

The modern machinery

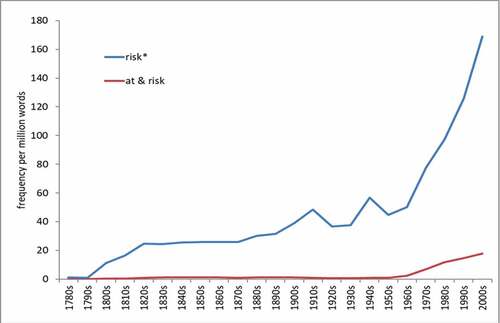

The rational approach to health and illness rests on what I have called ‘the modern machinery’, the practices of rational decision-making and generation of knowledge as institutionalised in science and insurance, for example, and are central to the historical modernisation process. Specifically, science comes with risk language. Even though this process started historically much earlier, shows a steep increase in the use of risk words and a robust increase of at risk-constructs from the 1960s and 1970s onwards. This parallels Skolbekken’s observation of a ‘risk epidemic’ in medical science journals during a similar time. But the at risk-construct is not only an increasingly used expression. It also occurs more and more often as the bigram ‘at risk’, without any additional complementing text in between (e.g., at serious risk). This would seem to indicate that ‘at-risk’ refers to a generally understood meaning, which does not require any additional linguistic clarification.

shows that the shift towards risk is mainly a development from the 1960s onwards. This is also reflected in the collocation analysis which examines the changing co-text of at risk in The Times. From the 1950s to 1960s, the risk mentioned closely to the at risk-construct was mainly war until from the 1960s onwards a growing number of words related to health issues occur. The table displays the 10 strongest at risk-collocates (compare with ).

Table 1. The risks – collocates of ‘at *** risk of/from’ the 1950s to 2000s

These collocates such as battering, injury, pregnancy, disease, heart, Aids, infection, abuse, cancer, starvation, BSE, attack, and diabetes refer to different issues and problem constellations, which relate to the modern machinery that rationally approaches and manages threats to health.

Health risks, indeed, are not restricted to illnesses. In the early 1960s, with the increasing application of x-ray technology in paediatrics, evidence showed that unexplained injuries of babies and children were often not the result of yet unknown illnesses or genetic conditions but regular and systematic abuse by their carers (Crane, Citation2015). Parton (Citation1979, p. 439) suggested that even though there was some publicity of the problem, it was given a low profile by the media at the time until the official inquiry into the death of Maria Colwell in 1973. Throughout the 1970s, an ongoing stream of child abuse scandals (compare Parton, Citation1979: 450, footnote 67) kept the issue on the public agenda.

The occurrence of the at risk-collocates battering, abuse, harm, and injury is connected to historical social changes during which the abuse of children became recognised as a social problem (Ferguson, Citation2004; Hendrick, Citation1994). But also, the reporting of child abuse changed. In early reporting, it was often assumed that the victim was somehow involved in and partly responsible for the abuse (Delap, Citation2015; Smart, Citation2000). With the use of the at risk-expression, the victim was mainly considered innocent but generally vulnerable to others or to a complex set of conditions.

He [Health Minister] undertook to re-examine the case for giving social workers the power to have a medical examination earned out on a child at risk of abuse. (1988_04_30)

He added that children were at no greater risk of abuse in boarding schools than they were in any other residential setting away from home. (2002_03_25)

He pioneered the use of covert video surveillance to identify children at risk of child abuse. This showed children aged 2 months and 44 months being deliberately injured in hospital by their parents or stepparents. (2007_12_05)

The analysis shows that once the concept of ‘at risk of abuse’ was established its application further broadened partly beyond the domain of health and illness. The analysis found financial abuse, drug abuse, elderly abuse, mentally ill abuse, and human rights abuse. ‘At risk of abuse’ eventually defines a complex set of conditions being responsible for a specific social group or entity experiencing the possibility of harm.

The collocate pregnancy is also connected to technological advancements but the discourse is not so much linked to health risks as socio-economic risks. Indeed, in the first half of the 18th century pregnancy was still accompanied by 55 deaths per 1,000 births (Chamberlain, Citation2006). With the advancement in hygiene and medical technologies, pregnancy and childbirth in the Western world has become a comparatively safe experience with no more than 7 deaths per 100,000 live births in the UK (WHO et al., Citation2019). In the 1970s it was the economic costs of young and underaged women, illegitimate children, or unwanted pregnancies more generally, which became the key issue in public debate. With medical research providing a new, cheap, and reliable contraception, called ‘the pill’, it was only a question of organising their social availability to at risk-groups to reduce the social costs of unwanted pregnancies. The debate was triggered at a time when fundamental changes in public attitudes to sex and family planning had taken place since the late 1960s (Leathard, Citation1980; Weeks, Citation2017) increasingly welcoming women’s opportunity to exercise control over their bodies.

News coverage of the early 1970s was informed by these debates and reports of the need to educate young women in particular, considered being at risk of pregnancy. This included informing about the most reliable forms of birth control and to make the pill available through the NHS to low or no cost:

The survey found that 93% of all married women at risk of pregnancy used some form of contraception, but 30% used the least reliable methods such as (1973_07_19)

“But we cannot escape the fact that some young people are sexually active and at risk of pregnancy from an early age” he said. In 1976 27,104 abortions and 19,800 illegitimate live births … (1978_04_15)

Technological advancement, in this case the development of efficient contraception, helped to manage a social problem. The debate resulted in a solution and ‘at risk of pregnancy’ disappeared from the news, indicating the success of the modern machinery. However, the continuous and growing stream of infectious and chronic diseases amongst the top 10 at risk-collocates indicates that the modern machinery might not always provide quick solutions for the healing and management of health.

There is good evidence that the use of at risk-language is connected to the growing significance of chronic and civilisation diseases (see, for example, Kurylowicz & Kopczynski, Citation1986). Even though infectious diseases did not disappear, significant health risks of our times are cardiovascular diseases, which are connected to modern lifestyles. In the 2000s, diabetes entered the top 10 at risk-collocates the first time. Such ongoing health issues are accompanied by different forms of cancer. Even though ongoing research has improved success rates of healing, many forms of cancer are still a severe health threat; thus, the modern machinery has only partly fulfilled its promise to successfully manage health risks. Therefore, it is no surprise that these illnesses remain amongst the 10 strongest at risk-collocates over decades.

The collocates heart, attack, and disease mainly refer to medical expertise and the (alleged) factors which influence the likelihood of the onset of a disease:

… older women who have a narrow choice of contraceptive methods because their weight, blood pressure or smoking puts them at risk of heart problems if they take the pill. (1983_04_13)

DOCTORS may be better able to predict when someone is at risk of having a second heart attack by using a test that measures … (1990_06_07)

SEVERAL short sessions of exercise can be just as beneficial to men at risk of heart disease as a single lengthy burst of activity, scientists have discovered. The first study of … (2000_08_29)

Cancer in the 1990s and 2000s mainly refers to breast cancer (f = 62), followed by skin cancer (f = 14) and lung cancer (f = 13). Debates are about treatments and lifestyle choices, which might affect the likelihood of developing one of these. Their occurrence almost always comes with scientific evidence or research, a study or conference.

The data show the growing co-occurrence of civilisation and chronic diseases, but infectious diseases have not disappeared. Even though about 50% of the articles on the risk of infection in the 1980s and 1990s relate to HIV/AIDS, there is also a wide range of other illnesses and threats, such as hepatitis B, goat milk, meningitis, salmonella, and the risk of animals transferring infectious diseases to humans, which all contribute to the instantiations of ‘at risk of infection’. What the discourse in all these cases shares is as follows: First, a notion of enlightenment, which highlights the risks people expose themselves or others to in everyday life. Second, the responsibility to prevent and reduce risk. Third, the efficient use of the means for specific ends. Fourth, the ethical management of risk, which means to overcome or improve an undesired situation according to shared social values.

The 1980s were the defining decade of the onset of HIV/AIDS, which is reflected in AIDS becoming a strong collocate of at risk. Over the following decades, advances in medical research contributed to HIV/AIDS, at least in the Western world, losing its character of a deadly disease. With HIV taking on the character of a chronic disease, media coverage on HIV/AIDS declined (Berridge, Citation1996). Major issues in news coverage have been groups at risk of infection, contracting and developing AIDS, and strategies to manage the illness:

… three quarters of sufferers belong to the main ‘high risk’ category: homosexual men, who are most at risk of contracting Aids through sexual intercourse with male partners. About one-fifth are drug abusers … (1985_02_21)

He said that safety of blood supply was maintained by giving all potential donors a leaflet asking those at risk of Aids not to give blood and by testing all blood donations for evidence of infection. (1987_01_17)

The BMA medical academics also decided that doctors must not discuss the cases of patients found to be at risk of Aids infection without their consent. (1987_06_09)

Thus, being at risk of infectious diseases is still an issue, but it is less a specific disease but a range of diseases, which require a scientific approach to prevent infection and managing the disease. AIDS mainly stood out because it was an unknown illness with no treatment available. AIDS was also socially explosive, from the early stigmatisation of homosexuals to a growing recognition of same sex forms of living and respective legislation which is also reflected in the data.

Similar to HIV/AIDS, the debate about BSE (Bovine spongiform encephalopathy or Mad Cow Disease) was shaped by the potential scope – everyone could be affected – and the uncertainty involved. BSE is a fatal neurodegenerative disease in cattle which became known in the 1980s and widespread in public debates in the 1990s. Early in the debate, experts suggested that animals were infected by carcases of sick and injured cattle or sheep, which were included as a protein supplement in cattle feed. This practice, which had been widespread in Europe, was therefore banned in 1988. The debate became politically disruptive, however, when concerns increased that BSE would be responsible for the occurrence of a new variant of the deadly Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (vCJD) in humans (Wales et al., Citation2006, p. 187). Experts suggested that BSE could be transmitted to humans by eating food contaminated with the brain, spinal cord, or digestive tract of infected carcases. In 1988 there had been policies for slaughtering infected beef while in 1989 a ban of high-risk beef products (brain, spinal cord, and spleen) was in place. The debate was about three themes, the possibility that humans would become infected, the management of BSE within the UK, and the harm done to the British beef industry caused by the ban of British beef by other countries and the EU.

Of course, humans are theoretically at risk of catching BSE. (1994_02_07)

Mr Hogg ‘s plan to cull up to 80,000 cattle, mainly dairy, considered to be at high risk of developing BSE, British farmers and vets had denounced the scheme as irrelevant and unjustified. (1996_05_22)

In an eleventh-hour attempt to avoid legal action, Britain last night made a fresh attempt to reassure France that cattle at any risk from BSE (bovine spongiform encephalopathy) would be removed from the food chain. (1999_11_16)

While the management of the infected cattle was somehow effective after slaughtering large numbers of cattle, the danger to humans appeared to be still minimal since deadly Creutzfeldt-Jakob diseases in humans remained extremely small. Thus, it was mainly the communication and (alleged) mismanagement of the risks, which triggered the public debate (see Dressel, Citation2002). The Times mainly reported on the management of cattle at risk of infection and the desire to lift the EU ban on British beef.

In summary, the instantiations of ‘at risk’ were related to the advancement of medical knowledge and technological innovation which provided the means to manage illnesses and discover the sources of ill-health. Where the modern machinery was not able to provide cure or control illness, there was an ongoing stream of reporting on the advancements and limits in the management of health and illness. Sometimes, the reasons for the use of at risk-language are less related to health but to social struggles. Examples have been the social rather than medical causes of illness as in the case of child abuse, and the new spheres of political action opened up by ‘the pill’.

In the following section, I examine how new knowledge and the institutionalisation of science and health services contributed to a new social consciousness connected to at risk-language.

The social management of risk

The expression that something of value is at risk only occurred infrequently during the 19th century in The Times but has become more frequent in the 20th century. The numbers were still relatively low in the first half of the 20th century (compare with ) while the thematic focus was economics and maritime trading. The dominance of collocates referring to economic issues, such as amount, property, and value and in the 1950s capital and amount illustrate this point. There is only one exception, the collocate population (compare with ).

Table 2. Objects ‘at risk’, noun collocates in The Times (London), 1900 to 2009

The occurrence of the collocate population connects to the success and institutionalisation of epidemiological knowledge. Already the mid-1800s witnessed the landmark study of John Snow (Citation1854) on cholera outbreaks in the UK including the famous 1854 Broad Street Pump outbreak in London, which had been contested at the beginning (Eyler, Citation2001). The successful institutionalisation of epidemiology as a discipline took another century (Rothman, Citation2007). In the 1930s and 1950s, the notion of at risk-population occurs in articles, which discuss epidemiological knowledge and reasoning and is bound to the context of research, a scientific report, and as part of a measure or calculation:

It is impossible to estimate how many more cases will be notified, but as the polluted supply was geographically limited and the population at risk was no more than one-twentieth of the total population of the borough, it is not anticipated that they will be numerous. (1937_11_13)

This total of 15 in six years seven months, with an average population at risk in the neighbourhood of 6,000, gives an annual suicide rate of 38.0 100,000 living Oxford University students. (1953_09_05)

The impression that ulcers occur more often in young men is due to a failure to take into account the relative size of the population at risk. (1957_05_10)

With the epidemiological concept becoming part of the socio-cultural repertoire of society it is regularly used without any discussion of the scientific underpinnings. Since the 1970s, at risk population started to spread to other contexts such as crime, war, economics, famines in the Global South, species at risk of extinction and finally global warming. With the spread of the notion of population at risk, the concept became sometimes detached from the epidemiological, evidence-based approach, and increasingly characterised as a generally assumed condition of a valued object. Formal scientific evidence can then become replaced by expert advice, everyday wisdom, or cultural expectation. Especially noteworthy is the shift from at risk populations in the 1960s to a large number of collocates, which refer to social groups considered vulnerable such as children, (old and young) people, patients, workers, babies, and women. The large proportion of articles referring to children are due to the scandal of widespread child battering and abuse while many articles refer to all kinds of issues where children are presented as vulnerable, such as parents not knowing how properly to fit a child seat in their car.

However, the epidemiological risk is increasingly complemented by a general risk concept, which determines the quality of a valued object by its at risk-status. There is also a clear tension between the evidence-based use of at risk, and the ethical use of at risk when the underpinning evidence can be vague or missing altogether. Indeed, both aspects often combine to different degrees.

An interesting case of the increasing frequency of at risk-language is the institutionalisation of the National Health Service (NHS) founded in 1948, which has been welcomed as a major social achievement by providing comprehensive, universal, and free health service for UK residents (Klein, Citation2010; Webster, Citation1988). The collocate patients is closely linked to the NHS and mainly occur in the context of reporting on the quality and the costs of service delivery and the ongoing industrial conflicts between staff and their unions and the government in the 1970s and 1980s (compare , 1970s: f = 34 [2.56/k], 1980s: f = 89 [3.24/k], 1990s: f = 136 [3.86/k], 2000s: f = 193 [3.66/k]).

During the 1970s the British economy was beset by multiple problems, while the Labour government of James Callaghan tried to keep inflation at bay through arrangements with the unions to limit pay rises. However, while the union leadership agreed with the government on pay restraint for improved benefits, major strike actions were initiated at the local level where shop stewards disregarded the agreement. During the so-called Winter of Discontent in 1978/1979, widespread strikes particularly in the public sector helped the Conservatives to win the following election with the new Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, subsequently contributing to reducing the power of the trade unions. In this context, the strike action of doctors and nurses was debated as putting patients’ health or even lives at risk (Hayward & Fee, Citation1992; Muyskens, Citation1982), an argument which reoccurred in the early and late 1980s:

The chairmen of the five groups in the Birmingham Regional Hospital Board’s area said yesterday that Monday’s statement by 300 of the city’s consultants that the dispute was putting patients increasingly at risk confirmed their own views (1973_03_14).

In the Government’s view, it is indefensible that any patients should remain at risk while the discussions arranged by the review body take place and pending the further talks which the Government have offered to both junior doctors and consultants (1975_12_02).

Here the notion of at risk no longer referred to scientific knowledge but the moral standards of staff putting vulnerable people at risk. During the 1990s, after industrial action was no longer a theme with unions’ power decreasing, the collocate patients refers to another set of issues such as the growing numbers of foreign doctors practising in the UK, overstretched personnel, bad practice in hospitals, and doctors behaving irresponsibly. At the end of the 1990s and the 2000s, there were a growing number of cases (one-fifth), which focused on doctors as a risk to patients, whether this was attributed to a lack of skills, inappropriate attitudes,Footnote4 or even criminal activitiesFootnote5 and triggered efforts to re-establish public confidence in the NHS (Alaszewski, Citation2002).

While the example of patients at risk mainly emphasises specific contextual conditions, which threatens the health and wellbeing of patients, there is also an indication for at risk being a quality of people and valued objects. This is the case with the hyphenated adjective at-risk (1980s, f = 33, 1990s, f = 47, and 2000s, f = 256) but also in a number of cases where patients at risk comes with a positive framing, such as in the reporting on new medicines and treatments, even though occasionally interspersed with high-profile scandals:

A study at the University of California-Davis showed that a mug of cocoa or a bar of chocolate have a similar beneficial effect on the blood as a low dose of aspirin, which doctors already recommend to patients at risk of developing the disease (2001_09_04)

Merck, the German drugs group, knowingly put patients at risk by relying on limited animal studies to claim that Vioxx would not harm the human heart (2005_07_15)

But doctors hope that the anticoagulant pill could also be used to treat thousands of other patients at risk from heart conditions and strokes (2008_03_10)

The positive framing is an interesting observation and complements the common assumption that risk comes overwhelmingly with a negative meaning (Hardy & Colombini, Citation2011: 472; Hamilton et al., Citation2007, p. 178).

From the early epistemological definition of at risk-populations which is defined by scientific evidence to the morally framed exposure of vulnerable groups to risk, the frequency of at risk significantly increased and spread across more and more social domains and applications. This comes with instantiations when at risk describes the quality of a social group. There is also a clear tendency of news coverage in The Times focusing on the unreasonable and unethical exposure of people or valued objects to risk.

Unreasonably put at risk

The example of the collocate patients and the NHS has already touched on the social expectation that institutions function well. This is the case for the NHS as with other infrastructures such as transport, buildings, and work. Accidents related to infrastructure and ‘at work’ were more common in early industrialisation while the expression safety at risk has become widespread during the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s (1970s: f = 8 [0.60/k], 1980s: f = 44 [1.60/k], 1990s: f = 58 [1.64/k], 2000s: f = 96 [1.82/k]). Particularly traumatic was the Zeebrugge ferry disaster in 1987 which resulted in the death of 193 passengers and crew and railway incidents such as near Clapham Junction in 1988, which caused the death of 35 people.

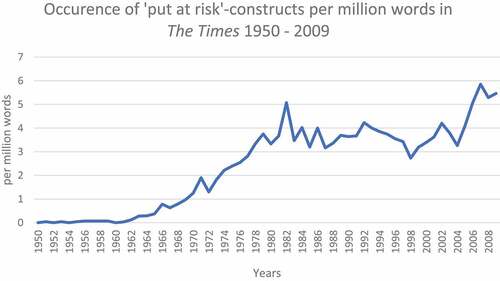

Across different social domains but specifically in the health domain put, putting and puts has a high affinity to at risk (Zinn, Citation2020, p. 146). The instantiations of the put at risk compoundFootnote6 as shown in suggest an increasing volume of such formulations in The Times reporting on people who are put at risk by others, by circumstances, or even by themselves.

Most frequent are cases in which circumstances or others put people at risk. There is only about 13% of cases in which people put themselves at risk:

Toxoplasma – a parasite found in raw meat, unwashed vegetables and in the faeces of mouse-catching cats – can put the unborn baby at risk if a mother-to-be becomes infected for the first time in early pregnancy (2000_06_24).

Dr Phil Hamond reveals how patients can be put at risk when undergoing specialist surgery at the hands of inexperienced staff. (2000_03_22)

Following the South Yorkshire traffic police as they track teenage car criminals and off-road bikers who put their lives at risk. (2005_08_24)

There is a clear indication that the news coverage of The Times is underpinned by the modern norm of rational decision-making (Weber, Citation1922), with an emphasis on risk minimisation and prevention. The reality of vulnerable people being put at risk by decisions of others, their negligence, or even their own unreasonable activities is newsworthy in a world where individual well-being and safety are of high value.

Discussion

The analysis of The Times news coverage provides a differentiated account of health issues driving the proliferation of at risk-language. The development of epidemiology and the notion of the at risk-population became embedded within socio-cultural lifeworlds via the institutionalisation of epidemiology as a discipline after World War Two. There is no doubt that the proliferation of risk language is linked to the development of epidemiology in tandem with population health. The empirical calculation of the future is part of the social rationalisation process, which has manifested in the development of scientific knowledge, social institutions, and practices. These combine to constitute a modern machinery that manages social challenges such as HIV/AIDS, cancer, and infectious and cardiovascular diseases. When issues are seemingly resolved, they disappear from the news media but there are also ongoing challenges which keep the at risk collocates of cancer, heart, attack, and infection amongst the top 10 at risk-collocates.

With several social groups populating the top 10 collocates of valued objects at risk, the epidemiological concept at risk-populations loses ground. Vulnerable groups do not necessarily refer to epidemiological evidence. Instead, at risk-language is also instantiated to make moral statements and express the urgency of a response. Thus, at risk-language can also be possibilistic (generalised possibility of harm) rather than probabilistic (likelihood of harm). What both versions of risk share is the norm that people should not put others or themselves unreasonably at risk. In this way, at risk-language is instantiated in the context of a social consciousness of a rationalised worldview that has become typical for Western societies. At the same time, it is mainly the same groups which are reported vulnerable – such as patients, children, women, and (young/elderly) people reflecting social inequality structures of society.

Technological innovation, ongoing medical research, unresolved and chronic health issues, and related social issues have all contributed to the public debate on individual well-being and risk exposure, which increasingly dominate reporting in the media. This shift started before the digitalisation of media production through the Wapping revolution (Conboy, Citation2010, p. 142) in 1986, but the increase of pagination certainly supported this trend, giving increasing space to new forms of journalism such as the new features and opinion sections. While at risk-constructs are instantiated in large numbers in the news section, the size of the features and opinion section grew over time and with them the frequency of at risk-constructs (Zinn, Citation2020: 197 f.). This is an indication that the new genre of contextual journalism (Fink & Schudson, Citation2014) and a stronger focus on debate, rather than mere reporting (Jucker & Berger, Citation2014), also comes with growing at risk-instantiations referring to both scientific evidence and moral debate.

The media, including the more conservative news media such as The Times, broadened their themes and included more lifestyle, well-being, and health topics to attract diverse audiences including more female readers as well as advertisers. It should not be forgotten that these changes took place at a time which heralded a significant socio-cultural shift, which included a growing focus on subjective experiences, individual well-being, and fitness (for example, aerobics, jogging, gym, and Pilates) and healthy and politically correct eating (such as consuming fairtrade, organic, vegetarian, or vegan produce). Indeed, this shift seems to run parallel to the growing frequency of the at risk-expression, which was driven by both the growing pervasiveness of risk language in health studies and the norm of self-improvement and risk minimisation.

The analyses support the view that mainstream approaches to risk such as the cultural approach, the risk society, and the governmentality perspective complement, rather than exclude, one another in the explanation of the growing pervasiveness of risk in present-day societies. Technological advancement provided new resources to manage the future, but the modern machinery continued to work on remaining unknowns and incalculable spheres. Rather than provide healing or ultimate solutions, forms for managing the uncontrollable became institutionalised in a stream of news on the most recent advancements (not least in cancer treatment). At the same time, media coverage reinforces new subjectivities of self-responsible behaviour to improve population health, which utilises a growing cultural desire in self-exploration and self-improvement. These developments are reinforced by the news media, which scandalise breaches and irresponsible behaviour that puts people at risk, while simultaneously encouraging compliance.

The case of COVID-19 evidences that health concerns are high on the public agenda and that epidemiological expertise has a significant influence on the debate and social management of the pandemic. However, the alleged evidence about risk is instrumentalised to silence critique and to push political agendas. This is expected but with the risk being a value-based concept these underpinnings have to be addressed in research and social practice. The media coverage on COVID-19 in the UK has also exemplified that the modern narrative of rationality does not count for everyone in the same way. There is good evidence that the opportunities and rights to behave irresponsibly are unequally allocated (Zinn, Citation2012). The repeating breach of lockdown rules by Dominic Cummings, who was at the time the UK Prime Minister’s advisor, is only one prominent example (Davies & Dellanna, Citation2020).

Conclusions

With risk having become an increasingly influential social practice and moral discourse shaping the understanding and management of health and illness, critical questions have to be asked about the negative and positive effects of such changes and how they might influence research. Indeed, a critical sociology of risk and uncertainty would have to resist a narrow clinical and epidemiological focus on risk as well as to exclude the broader social practices related to the social understanding and management of health and illness (for a debate, see Green, Citation2009; Zinn, Citation2009). Rather than to abandon risk, the major task for research remains in examining how the dominant narrative and social practice of risk relate to other practices of people, organisations, and societies as these engage with and manage understandings of health and illness. Part of this examination would include, as I have shown above, how the various meanings of risk change over time and are allocated unequally within society.

Acknowledgements

This publication is based on research conducted at the ESRC research centre Corpus Approaches to Social Science (CASS) at Lancaster University (Jul 2016-Dec 2018). It was funded by the European Commission through its Horizon 2020 Marie Skłodowska-Curie Individual Fellowship action (Grant Number 701836, H2020- MSCA-IF-2015). I am grateful for the funding and the anonymous reviewers’ comments and suggestions as well as the editor’s support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. A ‘Risk word’ is defined as any lexical item whose root is risk (risking, risky, riskers, etc.) or any adjective or adverb containing this root (e.g., at-risk, risk-laden, no-risk; Zinn & McDonald, Citation2018, p. 70).

3. Zinn and McDonald (Citation2018) successfully used a similar approach for the historical change of risk words in the New York Times.

4. During the 1990s at the Bristol Royal Infirmary, babies died at high rates after cardiac surgery as a lack of skills and cover up allowing harmful practice to continue over a decade. The Stafford Hospital Scandal in the 2000s resulted in an investigation and attempts to improve and monitor service quality.

5. A high-profile case was the mass murderer Harold Shipman, a general practitioner who was found guilty in January 2000 of killing 15 of his patients while his total number of victims has been estimated about 250.

6. ‘put at risk’ constructs are all constructs with up to three words in between the lemma ‘put’ and ‘at’ and ‘at’ and the noun lemma ‘risk’: {put} *** at *** {risk/N}.

References

- Alaszewski, A. (2002). The impact of the Bristol Royal Infirmary disaster and inquiry on public services in the UK. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 16(4), 371–378. https://doi.org/10.1080/1356182021000008319

- Allan, S., Adam, B., & Carter, C. (2000). Environmental risks and the media. Routledge.

- Althaus, C. E. (2005). A disciplinary perspective on the epistemological status of risk. Risk Analysis, 25(3), 567–588. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2005.00625.x

- Baker, P. (2006). Using corpora in discourse analysis. Continuum.

- Battistelli, F., & Galantino, M. G. (2019). Dangers, risks and threats: An alternative conceptualization to the catch-all concept of risk, risks and threats: An alternative conceptualization to the catch-all concept of risk. Current Sociology, 67(1), 64–78. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392118793675

- Beck, U. (1992). Risk society: Towards a new modernity. Sage.

- Beck, U. (2000). Foreword. In S. Allan, B. Adam, & C. Carter (Eds.), Environmental risks and the media (pp. xii–xiv). Routledge.

- Beck, U. (2009). World at risk. Polity.

- Berger, P. L., & Luckman, T. (1966). The social construction of reality. A treatise in the sociology of knowledge. Anchor Books.

- Bernstein, P. L. (1996). Against the Gods. John Wiley.

- Berridge, V. (1996). AIDS in the UK: The making of a policy, 1981–1994. Oxford University Press.

- Boholm, M. (2012). The semantic distinction between “risk” and “danger”: A linguistic analysis. Risk Analysis, 32(2), 281–293. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2011.01668.x

- Chamberlain, G. (2006). British maternal mortality in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 99(11), 559–563. https://doi.org/10.1177/014107680609901113

- Conboy, M. (2002). The press and popular culture. Sage.

- Conboy, M. (2010). The language of newspapers: Socio-historical perspectives. Continuum.

- Crane, J. (2015). The bones tell a story the child is too young or too frightened to tell. The battered child syndrome in post-war Britain and America. Social History of Medicine, 28(4), 767–788. https://doi.org/10.1093/shm/hkv040

- Crichton, J., Candlin, J., & Firkins, A. S. (eds.). (2016). Communicating risk. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Curran, J., & Seaton, J. (2018). Power without responsibility: The press, broadcasting and new media in Britain. Routledge.

- Davies, P., & Dellanna, A. 2020. Pressure builds on UK advisor to quit over new allegations he breached coronavirus lockdown. Euronews (24/05/2020) accessed 16 Sep. 2020 https://www.euronews.com/2020/05/23/uk-opposition-calls-for-top-government-aide-to-resign-due-to-alleged-coronavirus-lockdown

- Dean, M. (1999). Governmentality: Power and rule in modern society. Sage.

- Delap, L. 2015. Child welfare, child protection and sexual abuse 1918-1990. History and Policy, King's College London and the University of Cambridge. Accessed 16 October 2018 http://www.historyandpolicy.org/projects/project/historical-child-sex-abuse.

- Douglas, M., & Wildavsky, A. (1982). Risk and culture: An essay on the selection of technical and environmental dangers. University of California Press.

- Dressel, K. (2002). BSE – The new dimension of uncertainty. The cultural politics of science and decision-making. edition sigma

- Duguid, A. (2010). Newspaper discourse informalisation: A diachronic comparison from keywords. Corpora, 5(2), 109–138. https://doi.org/10.3366/cor.2010.0102

- Evert, S. (2009). Corpora and collocations. In A. Lüdeling & M. Kytö (Eds.), Corpus linguistics: An international handbook (Vol. 2, pp. 1212–1248). Mouton de Gruyter.

- Eyler, J. M. (2001). The changing assessments of John Snow’s and William Farr’s cholera studies. Soz Präventivmed, 46(4), 225–232. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01593177

- Fairclough, N. (1995). Media discourse. Arnold.

- Ferguson, H. (2004). Protecting children in time: Child abuse, child protection and the consequences of modernity. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Fink, K., & Schudson, M. (2014). The rise of contextual journalism, 1950s–2000s. Journalism, 15(1), 3–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884913479015

- Firth, J. R. (1957). A synopsis of linguistic theory 1930–55. In: Studies in linguistic analysis (Vols. 1-32). The Philological Society.

- Franklin, J. (ed.). (1998). The politics of risk society. Polity.

- Giddens, A. (1991). The consequences of modernity. Polity.

- Giddens, A. (2000). Runaway world. How globalization is reshaping our lives. Routledge.

- Green, J. (1997). Risk and misfortune: The social construction of accidents. UCL Press.

- Green, J. (1999). From accidents to risk: Public health and preventable injury. Health, Risk & Society, 1(1), 25–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698579908407005

- Green, J. (2009). Is it time for the sociology of health to abandon ‘risk’? Health, Risk & Society, 11(6), 493–508. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698570903329474

- Hacking, I. (1990). The taming of chance. Cambridge University Press.

- Hamilton, C., Adolphs, S., & Nerlich, B. (2007). The meanings of ‘risk’: A view from corpus linguistics. Discourse & Society, 18(2), 163–181. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926507073374

- Hardy, D. E., & Colombini, C. B. (2011). A genre, collocational, and constructional analysis of RISK. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics, 16(4), 462–485. https://doi.org/10.1075/ijcl.16.4.02har

- Hayward, S., & Fee, E. (1992). More in sorrow than in anger: The British nurses’ strike of 1988. International Journal of Health Services, 22(3), 397–415. https://doi.org/10.2190/CKJC-UGCX-DTFN-W9AK

- Hendrick, H. (1994). Child welfare: England 1872–1989. Routledge.

- Huan, C. (2016). Negotiating risk in Chinese and Australian print media hard news reporting on food safety: A corpus based study. In J. Chrichton, C. N. Candlin, & A. S. Firkins (Eds.), Communicating risk (pp. 216–266). Palgrave MacMillan.

- Jones, M. W. 1976. Deadline disaster. A newspaper history. Newton Abbot, Devon: David & Charles.

- Joulain-Jay, A. T. 2017. Corpus linguistics for history: The methodology of investigating place-name discourses in digitised nineteenth-century newspapers. PhD thesis, Lancaster University.

- Jucker, A. H., & Berger, M. (2014). The development of discourse presentation in The Times, 1833–1988. Media History, 20(1), 67–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/13688804.2013.879793

- Klein, R. (2010). The new politics of the NHS (6th ed.). Radcliffe.

- Koselleck, R. (1989). Social history and conceptual history. Politics, Culture and Society, 2(3), 308–325, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01384827.

- Kurylowicz, W., & Kopczynski, J. (1986). Diseases of civilization, today and tomorrow. MIRCEN Journal of Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2(2), 253–265. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00933491

- Leathard, A. (1980). The fight for family planning. The development of family planning services in Britain 1921–74. Macmillan.

- Luhmann, N. (1993). Risk. A sociological theory. Walter de Gruyter.

- Muyskens, J. L. (1982). Nurses’ collective responsibility and the strike weapon. The Journal of Medicine and Philosophy: A Forum for Bioethics and Philosophy of Medicine, 7(1), 101–112. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmp/7.1.101

- Nerlich, B., Forsyth, R., & Clarke, D. (2012). Climate in the news: How differences in media discourse between the US and UK reflect national priorities. Environmental Communication: A Journal of Nature and Culture, 6(1), 44–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2011.644633

- Parton, N. (1979). A natural history of child abuse: A study in social problem definition. British Journal of Social Work, 9(4), 431–451. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.bjsw.a057117

- Renn, O. (1992). Concepts of risk: A classification. In S. Krimsky & D. Golding (Eds.), Social theories of risk. Praeger, 53-79.

- Rosa, E. A. (2010). The logical status of risk – To burnish or to dull. Journal of Risk Research, 13(3), 239–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669870903484351

- Rothman, K. J. (2007). The rise and fall of epidemiology 1950-2000. International Journal of Epidemiology, 36(4), 708–710. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dym150

- Skolbekken, J.-A. (1995). The risk epidemic in medical journals. Social Science & Medicine, 40(3), 291–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(94)00262-R

- Smart, C. (2000). Reconsidering the recent history of child sexual abuse 1910–1960. Journal of Social Policy, 29(1), 55–71. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279400005857

- Snow, J. (1854). On the mode of communication of cholera (2nd ed.). John Churchill.

- Starr, P. (2004). The creation of the media. Political origins of modern communications. Basic Books.

- Wales, C., Harvey, M., & Warde, A. (2006). Recuperating from BSE: The shifting UK institutional basis for trust in food. Appetite, 47(2), 187–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2006.05.007

- Weber, M. (1922). Economy and society. University of California Press.

- Weber, M. (1948). Science as a vocation. In H. Gerth (Ed.), Max Weber: Selections in translation. CUP.

- Webster, C. (1988). The health services since the War, Vol. 1, problems of health care: The national health service before 1957. HMSO.

- Weeks, J. (2017). Sex, politics and society. The regulation of sexuality since 1800 (4th ed.). Routledge.

- WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United National Population Division (2019). Maternal Mortality: Levels and trends 2000–2017. Country profiles, UK, Accessed 28 September 2019 https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/maternal-mortality-2000-2017/en/

- Wodak, R., & Meyer, M. (eds.). (2015). Methods of critical discourse analysis (3rdedition ed.). Sage.

- Zinn, J. O. (2009). ‘The sociology of risk and uncertainty: A response to Judith Green’s ‘Is it time for the sociology of health to abandon “risk”?”. Health, Risk & Society, 11(6), 509–526. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698570903329490

- Zinn, J. O. (2012). More irresponsibility for everyone? In G. Hage & R. Eckersley (Eds.), Responsibility (pp. 29–42). Melbourne University Press.

- Zinn, J. O. (2019). Utilising corpus linguistic tools for analysing social change in risk. In A. Olofsson & J. O. Zinn (Eds.), Researching risk and uncertainty. Methodologies, methods and research strategies (pp. 337–366). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Zinn, J. O. (2020). The UK ‘at risk’. A corpus approach to historical social change. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Zinn, J. O., & McDonald, D. (2018). Risk in The New York Times (1987–2014). A corpus-based exploration of sociological theories. Palgrave Macmillan.