Abstract

This article analyses the apparatus of practices dedicated to reducing long-term diet-associated health risks so as to question how risk is framed and worked upon in everyday risk governance contexts. In 2020–2021, I conducted 10 semi-structured interviews with public & environmental health researchers and programme managers at both federal (Canada) and provincial (Quebec) levels, as well as with clinical practitioners (clinical physician, dietician). I also used these interviews and the information provided by my interviewees to gather a corpus of materials comprised of clinical protocols, empirical guidelines, governmental screening programmes, and more. In the analysis, I contrast testing practices dedicated to preventing and controlling chronic conditions associated with food ingestion such as type 2 diabetes, with others dedicated to predicting and preventing health conditions associated with the ingestion of pesticides and contaminants. I use Foucauldian discourse analysis methods as well as Sheila Jasanoff’s (1999) “songlines of risk” in her analysis of environmental risk assessment practices to analyse how the risk mitigation practices under study integrate different approaches to risk and thus different ways of caring for health and bodies. This leads me to a discussion on the biopolitical approach to risk and health that informs these practices and the apparatus they constitute, contributing to orienting where the onus of the responsibility lies when it comes to managing or preventing diet-associated health conditions. I argue that the apparatus plays a role in invisibilizing the environmental factors in disease causation and reinforcing the individualisation of health (responsibility) rather than its collectivisation.

In this article, I analyse the apparatus of practices dedicated to preventing long-term diet-associated health risks so as to question how risk is framed and worked upon. More specifically, I contrast two sets of practices as techniques of approaching risk, so as to highlight how they integrate different ways of caring (or not) for health and bodies.

This research interest comes out of previous research conducted on the role of “healthy food”’s construction in the reinforcement of the “obesity crisis” (Durocher, Citation2023) and its association with increasing incidence of chronic conditions such as diabetes. While conducting that research, I came across the work of an increasing number of scholars in social sciences (Gálvez et al., Citation2020; Guthman, Citation2011; Guthman & Mansfield, Citation2013; Hatch et al., Citation2019; Landecker, Citation2011) and in health and environmental sciences (Berman, Citation2022; Evangelou et al., Citation2016; Gupta et al., Citation2020; Neel & Sargis, Citation2011; O’Donovan & Cadena-Gaitán, Citation2018) who pay closer attention to the environmental causes of chronic and “non-communicable” conditions that are currently associated with the diet, including diabetes. More specifically, these works stress the necessity to pay further attention to the environmental pathways of diseases and health conditions that are still to this day largely associated with individual behaviours and lifestyles “choices” within popular culture and public health discourses. Observing the discrepancy between this critical research and what I was observing while conducting my fieldwork in Quebec/CanadaFootnote1 analysing various health and healthy food promotion discourses, I started wondering: how are long term diet-associated risks actually managed by health experts and authorities in Canada? And how are environmental risks part of the equation?

This analysis focuses on two sets of practices: testing practices dedicated to preventing and controlling chronic conditions associated with food ingestion such as type 2 diabetes, and others dedicated to predicting and preventing health conditions associated with the ingestion of pesticides and contaminants. I approach these practices as constitutive of the apparatus developed in Quebec/Canada to manage health risks associated with food consumption. I am drawing here on Foucault’s use of the term “apparatus”, especially in his analysis of the politics of health in the 18th century (as cited in Rabinow & Rose, Citation2003), to describe a heterogeneous ensemble of elements (including institutions, policies, laws, tools and technologies, discourses, measures, among others) meant to manage and control certain (biological) characteristics of a population: “The biological traits of a population became pertinent elements in its economic management, and it was necessary to organize them through an apparatus that not only assured the constant maximization of their utility but equally their subjection” (Excerpt from Foucault, Citation1976, p. 18, translated and cited in Rabinow & Rose, Citation2003, pp. 10–11). Rabinow and Rose (Citation2003) highlight how, for Foucault, the apparatus “[…] embodied a kind of strategic bricolage articulated by an identifiable social collectivity. It functioned to define and to regulate targets constituted through a mixed economy of power and knowledge” (p. 10–11). Influenced by feminist materialists and STS scholars who pay attention to the becoming of materialities (Abrahamsson et al., Citation2015; Pitts-Taylor, Citation2016; Alaimo & Hekman, Citation2008), I am particularly interested in the testing practices that are part of this apparatus in that they contribute to producing knowledge on bodies and health, and therefore further orienting their (organic) becoming.

Socio-cultural approaches to and critical analyses of the governance of health and risks (e.g., Clarke et al., Citation2010; Ehlers & Krupar, Citation2019; Harthorn & Oaks, Citation2003; Polzer & Power, Citation2016) and the role science and technologies play in this governance (for example, Braun, Citation2014; Doucet-Battle, Citation2021; Ehlers & Krupar, Citation2019; Lock & Nguyen, Citation2018) have revealed how risk is not a given, a pre-existent thing; it is constructed along with the existent tools and knowledge developed to circumscribe and assess it. While Mary Douglas (Douglas, Citation1992; Mary & Wildavsky, Citation1983) had already emphasised the inherently political nature of risk, STS scholars have since then further demonstrated that the science and technologies used to assess risk are not simply “neutral” (Braun, Citation2014; Lock & Nguyen, Citation2018; Murphy, Citation2006); they are permeated by ideologies that contribute to shaping how risk is defined, assessed and acted upon (or not).

Risk management is a central feature of how health is approached and governed nowadays, both at an individual and populational level (Adams et al., Citation2009; Clarke et al., Citation2010). Yet, sociologists, anthropologists, feminist STS and environmental justice researchers and activists, among others, have usefully demonstrated that risk, while currently highly individualised within Western neoliberal, biopolitical modes of governance, is political and unevenly distributed (Gravlee, Citation2009; Harthorn & Oaks, Citation2003; Murphy, Citation2006; Citation2017). In their work on biopolitics, Ehlers and Krupar (Citation2019), drawing on Foucault’s approach to biopower and life governance, argue that life-making, characteristic of biopower, is permeated by power(/knowledge) relations, and that it is inseparable from its correlate, “letting die”. While doing so, they demonstrate that “[n]ot all forms of life are fostered equally; indeed, the life possibilities of some are produced through limiting the lives of others.” (p. 4)

This perspective informs my approach in analysing how risk is framed and worked on in the context of the practices analysed in this paper. I pay attention to the power relationships at play in how bodies are cared for in this apparatus, which leads me to a discussion on the biopolitical approach to risk and health that informs these practices and the apparatus they constitute, contributing to orienting where the onus of the responsibility lies when it comes to managing or preventing diet-associated health conditions. I argue that the apparatus plays a role in invisibilizing the environmental factors in disease causation and reinforcing the individualisation of health (responsibility) rather than its collectivisation.

In the following sections, I first detail the methodology used to collect the materials analysed in this paper, while also providing more information on the practices in focus and how I analysed them. Then, drawing on Sheila Jasanoff (Citation1999)’s “songlines of risk” (causation, agency and uncertainty) and Foucauldian discourse analysis methods, I analyse the practices and compare how they approach and work on risk. I conclude by discussing the biopolitics of this apparatus, and what it means in terms of which bodies are cared for (or not) and how.

Methodology

In the “findings” section below, I develop an analysis of testing practices constitutive of the apparatus in place in Quebec/Canada to predict and inflect long-term health risksFootnote2 associated with food ingestion via organic materialities (through the testing of, among other things, blood, urine, food matters). To circumscribe the practices in focus and gather the materials under analysis here, I used a combination of methods. In 2020–2021, I conducted 10 semi-structured interviews with public & environmental health researchers and programme managers at both federal (Canada) and provincial (Quebec) levels, as well as with clinical practitioners (clinical physician, dietician). I used these interviews to collect information about the array of practices developed and used to monitor and control health risks currently associated with diet, whether linked to the management of nutrition or pesticides/contaminants, at an individual and populational level. I also used these interviews and the information provided by my interviewees to gather a corpus of materials comprised of clinical protocols, empirical guidelines, governmental screening programmes, food databases, screening reports, and more. My selection of these materials was driven by a focus on practices that either directly test food and bodily materialities, or which are informed by or related to such testing (such as a nutrient file database, or the Canadian Community Health Survey). Once I had a sense of the vast array of testing practices and their related activities, I decided to focus on two sets of testing practices (described below), as they directly involved organic materiality testing and as such contributed to orienting how risk was approached and worked on.

In the “findings” section below, I mobilise excerpts from the notes taken during these interviews as well as excerpts of documents from my corpus to support and develop the analysis. I use Foucauldian discourse analysis methods (also used by researchers from whose work I draw; Ehlers & Krupar, Citation2019) as well as Jasanoff’s (Citation1999) “songlines of risk” in her analysis of environmental risk assessment practices to analyse how risk is framed, approached and worked on in the context of the practices under analysis. Before I move on with the analysis, I briefly outline the practices in focus.

The practices in focus

Blood sugar

In the analysis, I focus on blood testing, done to evaluate the health status of bodies and assess the risk of developing metabolic/chronic conditions such as diabetes or high cholesterol. I restricted the analysis to diabetes prevention/control since it is currently the chronic condition that receives the most public attention, given its common conflation with “obesity” (see “diabesity”, McNaughton, Citation2013a; McNaughton & Smith, Citation2018). This type of testing practice is done most often in a clinical context, either when someone is brought to the hospital for an emergency or after a doctor completes a risk assessment and evaluates that there is an increased risk of developing diabetes. The results of these testing practices are also used at a population level when governmental authorities monitor the variation in number of cases diagnosed (for example via the Canadian Chronic Disease Surveillance System) to orient future health programmes and priorities, as well as epidemiological studies.

Pesticides/Chemical contaminants

The other set of testing practices I focus on here is concerned with monitoring and controlling the levels of chemical contaminants in foods and bodies. I focus particularly on two different testing practices. The Canadian Total Diet Study (TDS) is designed to evaluate levels of chemical contaminants in foods “that are typically consumed by Canadians” (Health Canada, Citation2003) and to watch the variation of these levels over time. The Bureau of Chemical Safety (BCS) is the entity within Health Canada responsible for establishing the threshold limits of chemical residue to be respected in the country; it is also the entity in charge of conducting the TDS. TDS testing practices are done either annually, on a pre-determined cycle basis or in response to a punctual food safety issue. It “provides estimate levels of exposure to chemicals that Canadians in different age-sex groups accumulate through the food supply” (Health Canada, Citation2003). The BCS relies on surveys conducted with or by Statistics Canada (such as the Canadian Community Health Survey) that help to determine what foods are included in “the Canadian diet”: testing done in the context of the TDS encompasses testing foods as they would be consumed. If something “abnormal” is observed via these monitoring activities, the BCS might carry out risk assessment activities and, if a significant risk is observed, risk management activities can be undertaken which can include the revision of thresholds, or new legislative interventions, among other possibilities.

In this analysis, I also pay closer attention to human biomonitoring activities, a set of human bodies’ testing practices. Human biomonitoring activities, as led by public health authorities at both the provincial and federal levels, consist of carrying out testing on body materials, usually collected in the context of population-wide surveys such as the Canadian Health Measures Survey (CHMS): “Biomonitoring is the measurement, in people, of a chemical or the products it makes when it breaks down. This measurement (called the level or concentration) is usually taken in blood and urine and sometimes in other tissues and fluids such as hair, nails and breast milk. The measurement indicates how much of a chemical is present in a person” (Health Canada, Citation2010). As is the case with food monitoring, human biomonitoring activities are used to watch over the varying amounts of chemical contaminants (this time in bodies) and make sure that these amounts respect the thresholds established by the BCS. These practices are also used to monitor trends over time and can influence risk management activities and inform further risk assessment analysis in that they provide useful information to assess the degree and source of exposure to various contaminants.

In the analysis that follows, I pay attention to these testing practices but also more largely how they are used to frame, assess and control the risk, hence what comes before and after the moment of testing: What triggers these practices? How are the materialities analysed? How are their results interpreted and with what effects? This is all part of how risk is managed.

Findings

The following analysis draws on Jasanoff’s (Citation1999) “songlines of risk” in her analysis of environmental risk assessment practices. She argues that, for risk to exist, to be perceived, and to be controlled, its elements – which she identifies to be causation, agency and uncertainty – need to be “sung”. By this she refers to how these three elements are incorporated into how risk is defined and assessed, including via scientific methods and quantitative risk assessment tools and techniques. In the upcoming sections, I analyse the practices in focus along with this framework/lens and bring forward how risk is framed and as such, acted upon for each set of practices. I conclude by a discussion on the biopolitical character of this diet-associated risk management apparatus.

Causation

Health risks exist only in their relation to the possibility of harm in the future; they are defined by their relation to an unknown future (Reith, Citation2004). The apprehension of harm in the future is what incites acting upon the risk, in the present (Adams et al., Citation2009; Reith, Citation2004). In order to act on risks, causation links are identified so that the harm’s possible progression/trajectory can be assessed, and so that causes could be acted upon. In this section, I pay closer attention to how causation is established and approached in both sets of practices.

Blood sugar

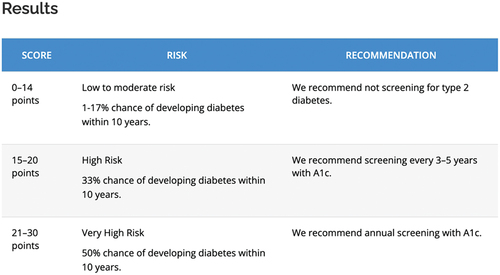

When it comes to preventing diabetes, testing practices are used to assess blood sugar levels. Chronic elevated blood sugar is feared for the future health problems it may lead to. Blood testing practices are involved in the screening and in the diagnosing of the condition. Screening includes non-invasive and invasive approaches (such as blood testing). Non-invasive screening techniques include an evaluation of “risk factors” such as age, weight (obesity most particularly), lifestyle habits, and the identification of “at-risk” populations (Diabetes Canada clinical guidelines 2021; Canadian Task Force clinical guide for diabetes screening 2016) using a questionnaire such as the FINDRISC (Finnish Diabetes Risk Score) or CANRISK (Canadian Diabetes Risk Questionnaire). Unless a patient is hospitalised or requires a medical consultation for a precise medical reason (for example, diabetes related symptoms) which would lead more systematically to direct blood testing, screening with non-invasive techniques is used on a more regular basis (such as an annual consultation). Screening using non-invasive approaches can lead to blood testing if the risk of developing diabetes is considered high (see ).

Figure 1. Printscreen of the FINDRISC score analysis grid (https://canadiantaskforce.ca/tools-resources/type-2-diabetes-2/type-2-diabetes-clinician-findrisc/). This grid is used in a clinical setting (non-invasive screening) to assess if blood test is required.

While screening via the evaluation of risk factors is not meant to determine causation, it has the effect of framing certain bodies as more at risk of disease incidence, given certain biological characteristics and/or behaviours (such as eating habits) (Fletcher, Citation2022; Rock, Citation2003; Shim, Citation2002). As many researchers have pointed out before me, this contributes to essentializing the causes of a condition at a biological/individual level (Gravlee, Citation2009; Hatch, Citation2016; Lock & Nguyen, Citation2018; Montoya, Citation2011; Shim, Citation2002).

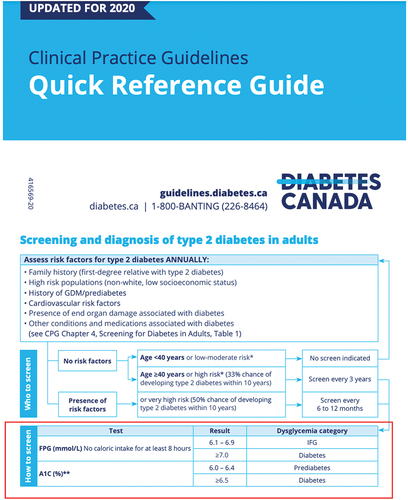

Risk factors are determined via epidemiological studies. Risk is identified via the analysis of an individual’s characteristics (including age, race, weight, potential health related behaviours), but in light of populational data portraying incidence or prevalence of a condition among a defined population. Epidemiology is also what underlies the diagnostic itself (see ), which brings the patient under the biomedical gaze.

Figure 2. Excerpt of the Diabetes Canada clinical guidelines featuring the diagnosis chart (https://guidelines.diabetes.ca/CDACPG/media/documents/CPG/CPG_Quick_Reference_Guide_PRINT_EN_2021.pdf). The tab with a red framing features the possible results of blood glucose while testing, and what it means in terms of clinical evaluation/diagnostic.

In her study of the treatment and identification of the causes of diabetes, Rock (Citation2005a) argues that “[…] diabetes is a disease not because of elevated blood glucose per se but because of the health risks this causes.” (p. 479–480) In other words, elevated blood sugar is not synonym of “unhealthiness” in the present per se, but it is approached as such since it leads to increased chances of developing microvascular (kidney damage, vision loss) and macrovascular complications in the future. As I have argued elsewhere (Durocher, Citationforthcoming), diagnosing brings the focus on future health risks to be mitigated, which means acting on blood sugar levels in the present. It does not explain what caused the long-term elevated blood sugar in the first place. The focus put on screening and diagnosing to prevent and controlFootnote3 shifts the gaze away from the many factors that can contribute to elevated blood glucose. Yet as Rock argues (2005), these factors can also contribute to higher risk of health conditions (including some currently associated with elevated blood glucose), “even if blood glucose levels do not (yet) meet the diagnostic criteria for diabetes.” (p. 479–480).

Thus, although screening and diagnosing do not lead to the identification of causes, they rely on epidemiological data to assume causal links: that identified risk factors lead to diabetes; that elevated blood sugar leads to future health issues. These statistically determined relationships, while not revealing what leads to elevated blood sugar or health conditions, have big implications for how the disease pathways are investigated (see next section on agency) as well as for the meanings that are attributed to bodily difference (see McNaughton, Citation2013a; Shim, Citation2002).

Pesticides/Chemical contaminants

Risk, or the possibility of harm, in the context of pesticides/chemical contaminants risk control is defined via the establishment of threshold limits, which determines what level of a given contaminant contained in foods or bodies is deemed “safe”. The TDS and the human biomonitoring activities investigated in the context of this study serve to monitor long-term variations or trends and make sure levels of contaminants in food and bodies respect the amounts authorised by the Bureau of Chemical Safety – the threshold limits. Risk assessment and the establishment of maximum residue amounts authorised in foods and bodies is done with the evaluation of exposure (such as for foods; combining the data on presence/concentration of chemicals with the data about what Canadians eat) and the potential hazard (evaluation of toxicity; characterising the dose-response of a chemical). The evaluation of the hazard is based on existent toxicological data, either within scientific literature or produced via “in-house experiments” (Notes from interview with BCS).

Many researchers concerned with environmental (in)justice and toxic exposure have taken issue with the thresholds’ paradigm in pesticides/contaminants risk control. They have pointed out that toxicological data is produced following a model where chemicals are singled out and their effect is analysed “out of context” (for instance, via toxicological studies conducted in a laboratory; Liboiron, Citation2021; Roberts, Citation2021; Saxton, Citation2021). They have also criticised that the threshold paradigm lacks consideration for (and capacity to trace back) the multiple cumulative exposures that do not necessarily follow a linear, graspable timeframe (Goldstein, Citation2017; Guthman & Mansfield, Citation2013; Landecker, Citation2011; Saxton, Citation2021) as well as for how critical periods of exposure change from one contaminant to the other (Guthman & Mansfield, Citation2013; Landecker, Citation2011; Langston, Citation2010; Liboiron, Citation2021; Vogel, Citation2013).

This is something the public & environmental health researchers and programme managers I interviewed acknowledged and took into consideration. Because of the limits of current knowledge and techniques but also because of the omnipresence of multiple contaminants in one’s environment and life trajectory and the variability of their effects, causal links between given contaminants and their effects on humans’ bodies and health are described as hard to assess and demonstrate:

[…] at the scale of the individual, […] it’s almost impossible, unless we talk of an acute intoxication, to prove scientifically – scientifically, not legally as we’ve seen in trials – that this disease, or this case is caused by this molecule, and you’ve been exposed during this period of your life … It’s almost impossible statistically. [… .] These are the limits of our field of work. (Excerpt from interview with INSPQ researcher)

Moreover, as my informants shared with me and as scholars concerned with environmental risks (Liboiron, Citation2021; Roberts, Citation2021; Saxton, Citation2021) have also argued elsewhere, current methods make it pretty much impossible to evaluate what some call the “cocktail effect”, which can refer to: a) when there is a multiplicity of sources of the same contaminant (such as through the air, or the water.), something current techniques allow more or less to track and that the toxicologists I have encountered take into account in their calculation of threshold limits; and b) when multiple different contaminants react together at the level of the organism, in ways that are too complex to be assessed by current techniques and knowledge:

That, it’s true, is probably the ‘poor parent’ of the toxicological evaluation. And in epidemiology in fact, because it is extremely difficult to measure what we are exposed to, really. All the more so because the combinations are in fact almost infinite. So even if in laboratory we study … 5, 10, 15 contaminants blended together in rats for example, well it still is only 5, 10, 15 while we are exposed to much more contaminants than that. […] So which contaminant is the most influential … influences the health outcome … .? How does it influence the other contaminants […]? It’s almost impossible to know. […] Norms, criteria, and risk evaluations are often for contaminants isolated; not in bad faith but because of the challenge of proceeding otherwise. So that’s why we try to be careful in our evaluation of risks when we suspect possibilities of interactions on the basis of what we know at a molecular level or something like that, to apply certain additional protection factors in the calculation. (Interview with INSPQ researcher)

In order to be able to manage risks despite these challenges (through legislation for instance), statistical calculations are used. As a researcher I interviewed from the Quebec’s National Public Health Institute (Institut national de santé publique du Québec; INSPQ) put it, it is all about a “balance of probabilities”:

[…] only one study isn’t sufficient to influence decisions such as public policies with regards to contaminants. It requires more than one study, led in different contexts, and if we see that finally, each time it’s the same link we observe, we end up … . It’s a balance of probabilities. It’s a kind of scientific consensus. […] There are nine causality criteria that are recognized: Hill’s criteria we call them in epidemiology. So, temporality: does the effect arrive after the exposure, that’s obvious. Is it repeated […]? Do we observe a dose-response relationship? Do we see that the effect is stronger when there are more substantial exposures? Are there mechanisms of action that can explain the relationship we observe? [… .] So when there are many elements together that converge, it’s not only a correlation, it’s a causal relationship. […] At a certain point, as an institution, we don’t wait to have all the answers to our questions to say ‘well … ’: at a certain point, we have enough evidence to say that there is a reasonable presumption that there is a link between this exposure and this risk. So we take action to try to limit the risk factors. (My emphasis. Interview notes with INSPQ researcher)

Links of causation are hence established via statistical tools that circumscribe what can be possibly acted upon (legislated, controlled, watched over, monitored). In other words, that means that the risks that can be apprehended and monitored are those currently ‘graspable’ with existing (statistical, epidemiological) methods and technologies, which cannot account for relationships still invisible to them or for processes that extend over periods of time that challenge classical dose-response timeframes (such as accumulation over generations) (Langston, Citation2010; Saxton, Citation2021; see also on care and what is “visible” or “seizable” Puig de la Bellacasa, Citation2017).

There are hence similarities in how causation is traced back or, more accurately, established, in diabetes risk prevention practices and pesticides/chemical contaminants ones: in both cases, risk assessment is done via abstract statistical calculations. In the context of diabetes, causation in risk analysis is established through the analysis of an individual’s characteristics or blood analysis, in light of statistical calculations of populational data. In the context of pesticides/chemical contaminants, threshold limits, exposure, and hazard are all calculated out of universal statistics that have little to do with an individual body whose risk and exposure are assessed in context. As Gabrielson (Citation2016) puts it, individual risks are “abstract[ed] […] through a universal language based upon a fictional body (the average body)” (p. 183). It is in some ways “disembodied” in that that risk is not associated with or thought of in relation to an actual individual, situated body about to ingest or ingesting, whose risk would be calculated on the basis of its testing.

Agency … & responsibility

In her analysis of environmental risk assessment, Jasanoff (Citation1999) highlights how risk is approached in an overly simplified way as emanating from inanimate objects, which increases humans’ sense of control over them. Yet she stresses that humans’ role in generating and enhancing risks is overlooked. Where does the agency lie when it comes to assessing and preventing risk in the two sets of practices? What does it mean in terms of who is held responsible or accountable, and therefore who needs to act to curtail the risk and/or how?

Blood sugar

‘Lifestyle habits, we also question them systematically: are you smoking, do you exercise? Diet … are you the type of person who cooks? Who eats out a lot? So when we do an annual exam, these are the things we ask systematically. And after that, on the basis of this information and in function of the patient we have in front of us, we push more or less to have more information.

[The interviewee mentions for example a patient who runs marathons, cooks, has their own garden …]

There are chances I won’t ask too many questions on their lifestyle habits, if they don’t have antecedents and if I see that they are thin and healthy. I will only do a little screening […] the classic though is the person who comes in our office, who we see is overweight, this is what we see the most I’d say, and that this person will have lifestyle habits … smoker, alcohol consumer, not very active, sedentary, who tell us they eat often at the restaurant […]. Well, for sure, these people have a baseline of cardiovascular risk factors, so it is among these persons that we will do metabolic screenings including for diabetes, lipids, tension, weight, waist circumference which are all predictors of cardiovascular diseases, chronic diseases. […] You look at clinical guidelines, the first-line treatment for hypertension is lifestyle habits; the treatment for diabetes, it’s lifestyle habits; the treatment of cholesterol, it’s lifestyle habits […]” (My emphasis. Excerpt from interview notes with family doctor)

The guidelines this family doctor is referring to are those recommended by the Canadian Task Force for the treatment and prevention of type 2 diabetes. These guidelines stress that change in lifestyle behaviours is key to diabetes prevention and treatment:

Individuals with a prediabetes diagnosis are strongly encouraged to undertake lifestyle modifications that include increasing physical activity, altering one’s diet and weight loss. It is estimated that a 5% reduction in initial body weight can reduce the risk of progression from prediabetes to type 2 diabetes by approximately 60% […] The goals of treatment for type 2 diabetes are similar to prediabetes treatment, in that lifestyle modification is a cornerstone of management. (Sherifali, Citation2011, pp. 9–10)

The results of the blood testing practices described in the previous section are interpreted in such a way that current health is assessed, future health is predicted and past behaviours that could have led to these results are investigated and targeted for change. As McNaughton and Smith (Citation2018) reveal, diabetes in Canada has increasingly been associated with obesity and framed as a matter of lifestyle factors:

From 2005 onwards, however, diabetes has moved up the list to rank as the first or second disease associated with obesity across key government websites, including Health Canada, the Public Health Agency of Canada, and various provincial ministries of health. But we also see another significant shift in emphasis in how diabetes is framed across these sites. From 2005 onwards, non-modifiable factors or causes of diabetes such as age, genetics, and family history have begun to slip into the background (and down the list), while those factors seen as modifiable lifestyle factors – notably weight, diet, and exercise – are given greater prominence. In short, there is a discernible shift in emphasis away from the non-modifiable to what is deemed open to change and intervention. (p. 131)

Change in weight and lifestyle behaviours (most particularly in diet and exercise) are framed as the cause of the condition as much as the solution to its treatment/management. In a context where health conditions such as diabetes are associated with the diet and with lifestyle “choices”, high blood sugar characteristic of type 2 diabetes becomes loaded with moral judgements as it is framed “as a disease of lifestyle [which] implies that like obesity, it is too self-inflicted – the result of wholly changeable and risky lifestyle factors […]” (McNaughton & Smith, Citation2018, p. 132; see also Bennett, Citation2019; Bombak et al., Citation2020; McNaughton, Citation2013a; Citation2013b). Even though “[t]he exact etiology for diabetes remains undetermined” (Bombak et al., Citation2020, p. 103) and there is currently no cure that exists for it, the measurement of the condition and of the “outcomes” of practices adopted to ”fix it” (via the analysis of the results of testing practices described above) make the condition appear as manageable, preventable.

Putting the emphasis on the individual’s behavioural change as a treatment (and cause) of the condition not only locates the condition within the individual body and puts the focus on individual responsibility, it also erases the “profound social and economic inequalities underlying incidence of the disease” (Rock, Citation2005b, p. 467; see also Rock, Citation2005a; Gálvez et al., Citation2020). The focus put on individual behaviour such as in the clinical procedures described here frames the individual as “in control” – autonomous and independent from contingencies and contexts – a move against which scholars who advocate for a reframing of diabetes as a “communicable disease” position themselves. In the context where disease causation pathways leading to diabetes are unclear, and where fraught and misleading associations are made between the condition and individual features or behaviours, these scholars argue that chronic conditions should be approached as the result of systemic and structural violence and inequities that contribute to the emergence and “spreading” (Gálvez et al., Citation2020; Hatch et al., Citation2019; Manderson & Warren, Citation2016; McCullough & Hardin, Citation2013; Moran-Thomas, Citation2020; Rock, Citation2003) of chronic conditions such as diabetes. Such a reframing would also bring a change in perspective on agency: rather than assuming that the individual is entirely autonomous, in control of their body/health becoming, it would bring a reframing of that agency as being distributed and shared.

Pesticides/Chemical contaminants

As discussed in the previous section, organic materiality testing practices are used to observe variations in levels of chemical contaminants contained in bodies and foods, trends, and act upon abnormalities when/if necessary. Health Canada acknowledges that there is “no systematic, comprehensive national surveillance of environmental exposures, food contaminants and risks” (Health Canada, Citation2005), one of the limits of its monitoring activities. Risk is rather assessed and controlled via the analysis of samplings and calculations of variations in averages. Health Canada also includes among the limitations of its biomonitoring activities (see ) the fact that it is often hard to know where/what are the sources or pathways of exposure since these practices consist of analysing bodies “after the fact”, once chemicals have already permeated the human body.

Figure 3. Screenshot from Health Canada’s website, exposing the limitations of biomonitoring activities and the data it generates (Health Canada, Citation2010).

The way risk is handled via this risk monitoring apparatus reveals how the focus is put on thresholds and therefore on the chemicals, even though their effects and their trajectory are hard to circumscribe with current tools and techniques. What matters in the context of these risk management strategies is not to investigate how given contaminants could interact with the specificities of a body exposed to various types of environmental stress (including the physical environmental, but also as linked to discrimination, social exclusion/isolation, poverty, and famine – see for instance Guthman, Citation2011; Manderson & Warren, Citation2016; Saxton, Citation2021), nor how risk could be assessed and controlled in a preventive manner (before ingestion). What matters is rather that levels observed in monitoring activities are within the thresholds already established.

As Jasanoff (Citation1999) observes in her analysis of environmental risk assessment, agency is attributed to the nonhuman contaminants, in that they are approached as what can have an effect on one’s health. Techniques and practices (such as monitoring activities and the establishment of threshold limits) are developed in order to circumscribe and control that risk. The focus on chemical control via the monitoring activities analysed here and the reliance on threshold limits avoids considering the agency of these chemicals as something that is distributed, done in context (Abrahamsson et al., Citation2015), so that the effect of a chemical may vary in different contexts and more specifically, in function of the array of processes and networks of elements it interacts with.

As mentioned above, as part of the acknowledged limits of the biomonitoring activities conducted in Canada, not all the foods produced, put into circulation and consumed in Canada are actually tested to evaluate the amount of residue they may contain, nor are all bodies monitored to identify levels of contaminants in them. That means that monitoring and risk assessment are not done for an individual body ingesting or about to ingest, and as such, they do not take into consideration the actual specificities of an individual body that is more exposed to chemicals (for example, through environmental racism), that has a history of exposure that extends over generations, and whose specific biology or biochemistry might be affected by various forms of violence (Gálvez et al., Citation2020; Liboiron, Citation2021; Manderson & Warren, Citation2016; Saxton, Citation2021). Considerations for differentiated, situated biology may come in envisioning different sources of exposure, such as through food, as explained by one of my interviewees: “For Northern populations [for example], because their diet is distinct, they may be exposed to higher concentrations of chemicals through the consumption of their traditional diet. The chemical response in the human body is not expected to be distinctly different, it is the differences in exposure that need to be considered.” (Interview notes with BCS) But considering different sources of exposure through different diets than that of the “typical Canadian” is different than considering the specificities of a body, and the traces various forms of structural violence have left in its materiality – which, admittedly, would be hard to investigate or demonstrate with the current scientific apparatus (see previous section on that).

The ubiquity and pervasiveness of a multiplicity of contaminants make it also hard to scientifically/empirically trace back links of causality between certain contaminants and diseases (Bowness et al., Citation2020; Langston, Citation2010; Saxton, Citation2021) and to disentangle the causal pathways among the multiplicity of contaminants already present in environments, bodies and foods (Saxton, Citation2021). In a globalised food system that relies heavily on pesticides and all sorts of chemical contaminants, it becomes hard to pinpoint and hold accountable one stakeholder; accountability, as explained by Health Canada in its Decision-Making Framework for Identifying, Assessing, and Managing Health Risks, is shared:

Health Canada has a primary role in protecting the health and safety of Canadians at the national level; however it is but one component of a complex system of health protection, which includes, among others, various levels of government, government agencies, the health care and medical professions, the academic and health sciences research and development communities, manufacturers and importers, consumer groups, and individual Canadians. (Health Canada, Citation2000)

This shared responsibility, as criticised by researchers concerned with toxic injustices, is what contributes to making it difficult to legislate and control the use and presence of contaminants, notably in foods and bodies (Langston, Citation2010; Liboiron, Citation2021; Nash, Citation2007; Vogel, Citation2013). Moreover, the way risks associated with pesticides/chemical contaminants are managed and controlled via the observation and analysis of long-term trends and variations (through the TDS and the biomonitoring activities) shifts the attention away from what contributes to the presence or omnipresence of the chemicals in the first place. In other words, the ubiquity and pervasiveness of the contaminants lead to monitoring strategies that pay closer attention to the chemical themselves (their levels in foods and bodies), shifting the attention away from who/what could be held accountable for the omnipresence of these contaminants in the first place.

Hence, in both diabetes and pesticides/chemical contaminants, testing does not lead to the identification of the causes of a possible health condition in the present or in the future, or to all the causes that could have led to what is framed as a risk (for example the presence of contaminants; elevated blood glucose). In the case of diabetes though, agency is attributed to the individual being tested, framed as both the cause and solution to the risks, and hence as bearing responsibility for them. In the context of pesticides/chemical contaminants, agency is attributed to the contaminants that have permeated organic materialities, with little attention to how that agency might be distributed, or to whom or what could be held accountable (responsible) for the (omni)presence of the contaminants in the first place.

Uncertainty

Risk is intimately linked to uncertainty; it is the uncertainty of the future, and the perceived possibility that it could be inflected, that leads to the development of tools and techniques to quantify and apprehend it. Risk analysis, through the characterisation and quantification of uncertainty, is meant to exert control over it, to the point where it becomes an event seemingly preventable, manageable (Reith, Citation2004). The two sets of practices analysed in the context of this article are dealing with lots of uncertainty with regards to scientific unknowns, to future health outcomes, and to the pathways of disease causation. Yet, they deal with it very differently. As Jasanoff (Citation1999) argues, the way we deal with uncertainty is political. How do the practices under study here frame and deal with uncertainty? In this section I build on the two preceding sections by looking at various forms of uncertainty previously identified and I question how they are acknowledged, addressed (or not), and embedded in the apparatus meant to control diet-related risks.

Blood sugar

In the two previous sections (causation & agency), I have discussed how causation is established through the association of individual characteristics and behaviours with the risk of developing diabetes, hence contributing to an individualising of risk and agency. Yet, the aetiology of the diabetic condition remains unclear. Critical obesity researchers in particular have been criticising how, despite the unknowns, the framing and management of diabetes risks assume links of causality that are detrimental to the individuals targeted. For instance, these researchers have highlighted how the relationship between weight/obesity and diabetes is far from clear as to whether obesity is a symptom or a cause (Bombak et al., Citation2020; Campos, Citation2011; Guthman, Citation2011; McCullough & Hardin, Citation2013; McNaughton, Citation2013b). The amalgamating of weight with diabetes does not leave room for considering that “some overweight or obese people never develop the disease, or […] that some people whose body weight is considered normal will be diagnosed with T2DM” (McNaughton & Smith, Citation2018, p. 133). These researchers have also stressed that the way treatment puts emphasis on lifestyle behaviour changes is not only detrimental to the individuals who are framed as responsible for their condition, but also might miss the point of proper intervention, as the association with certain specific foods to be consumed or avoided is unclear when it comes to chronic disease causation: “The links between diet and chronic disease are highly contested within the field of nutrition science; whether any specific dietary pattern can prevent chronic disease is unknown and perhaps unknowable. Recommendations to prevent chronic disease through dietary change persist not because they are supported by scientific evidence but because they are driven by complex social, political, and economic forces” (Hite, Citation2020, p. 652).

While links of causality remain unclear between the ingestion of particular foods and chronic diseases (Hite, Citation2020; also; Villines, Citation2022), the management of diabetes through the apparatus set into place assumes that they are, and hence investigates links between the “bad” lifestyle behaviours and the emergence or progression of the condition (see the section “Causation” above). This approach thereby decontextualises the condition from the multiplicity of potential causes and unknowns that are yet acknowledged by various researchers and health authorities but not necessarily clearly nuanced in how the condition is approached in various public health initiatives, medical encounters, and public and popular culture discourses (Bennett, Citation2019; McCullough & Hardin, Citation2013; McNaughton & Smith, Citation2018; Frazer and Walker Citation2021). As I mentioned earlier, this underplaying of uncertainty has important implications for how bodily difference is approached, but also for how the possible other causes of the condition, beyond the individual’s agency, are addressed or not.

Pesticides/Chemical contaminants

As I have highlighted in the sections above, there are limits to the thresholds paradigm and how risk is assessed and worked upon within the testing apparatus developed to control pesticides/chemical contaminants’ risks. All the experts I met with were transparent with regards to the limits of their practice, as well as with the limits of the knowledge they produce and work with. While these limitations were acknowledged (and often visibly exposed; see previous sections), this does not mean that the threshold approach to risk control is shattered; it rather means that more “precautionary measures” are used to compensate for uncertainty. The precautionary approach in the context of chemical contaminant risk management practices means that the thresholds authorised are lowered to account for unknowns such as with regards to how a “vulnerable” population would react to a specific contaminant; to the toxicity of a contaminant; to the “cocktail effect”, in order to “account for the variations in the biological responses in a population” (Excerpt interview notes with BCS). This approach is understood in relation to the “healthy worker effect” whereby studies are often conducted on healthy, working populations, which are not representative of the immense diversity of the population (see Gabrielson, Citation2016; Murphy, Citation2006 for a critical perspective). To compensate for this, precautionary measures are used, as explained by the experts I met. This does not mean though that, confronted with the unknowns, no use or presence of the contaminant would be allowed or tolerated.

Many researchers have demonstrated how delays in the production of scientific knowledge have benefited industries since the absence of demonstration of harm slows down legislative interventions and more stringent regulations (Henry, Citation2021; Langston, Citation2010; Murphy, Citation2006). The apparatus set into place in Canada to monitor and control risks associated with chemical contaminants at the time of my research seemed to resonate with what Langston (Citation2010, p. 114) describes as:

The assumption guiding quantitative risk assessment is that risk is an unavoidable fact of modern life, something to be managed rather than eliminated. […] Risk assessors then manage the danger from toxic chemicals by permitting them to be used as long as they do not exceed a standard of contamination deemed to be an acceptable trade-off for economic gains. Who decides what trade-offs are acceptable to whom is deeply contentious, of course.

This approach to risk management was well summed up by the INSPQ researcher I interviewed who commented on the use of norms as a regulatory measure to control risks: “A norm, in the end, is a permit to pollute […].”

Discussion: the biopolitics of diet-associated risk management practices

I explained in the introduction that I approach, in the context of this analysis, these risk related practices as constitutive of an apparatus intended to control the biological characteristics of the population and, more specifically, life. Foucault’s approach to the governance of life is intimately tied not only to the economy and the governance of health and the biological characteristics of a population (through biopolitics, for instance), but also to how “biological life comes to be known and conditioned through various mechanisms and techniques – power/knowledge relations” (Ehlers & Krupar, Citation2019, p. 2). I understand the practices I have analysed above as producing knowledge on bodies and health within the limits of what is currently possible/available (in terms of contemporary knowledge as much as in terms of technological advancement), while also contributing to orienting future actions undertaken to act on both these bodies and the overall health of the population. More importantly with regards to what I want to discuss in this last section, in their analysis of US biocultures, Ehlers and Krupar (Citation2019) stress that forms of “letting die” take form alongside strategies and imperatives to “make live”: “According to Foucault, “letting die” is integral to the biopolitical imperative to “make live” and entails various operations of abandonment, negligence, and oversight […]” (p. 4), hence contributing to encouraging certain lives more than others. Ehlers and Kruplar identify three interrelated forms of “letting die” at play in US biocultures: how life-making practices can “obscure death”, “create deadly conditions”, and “produce death and/or death effects” (p. 4–5). This is a useful lens to analyse the power relationships at play in the apparatus developed to manage diet-associated and contaminant-associated risks, and the differentiated health that such apparatus contributes to reproducing.

As I have mentioned while discussing how causation is established and drawn upon in the context of diabetes risk prevention/control, many researchers have criticised the risk factor approach to disease control and prevention since it contributes to a heightening surveillance on some racialised (Hatch, Citation2016; Montoya, Citation2011; Rock, Citation2003; Shim, Citation2002) and fat bodies (McCullough & Hardin, Citation2013; McNaughton & Smith, Citation2018), in contrast to others. This inequal structuring of surveillance contributes not only to individualising and essentializing a condition, such as diabetes, but also to fostering an increased medical gaze and stigma. The focus put on individuals’ agency with regards to the development and treatment of the condition contributes to shifting the attention away from the uncertainty with relation to the condition’s aetiology and the many possible pathways of disease causation, two elements that remain under-stated and more or less visible in public/clinical contexts. It also means that, presumably, pathways of disease causation that lie beyond individual control (such as environmental and social stressors and inequalities, for instance) are left underinvestigated (for instance, in clinical contexts) and therefore remain unchanged and unaddressed. This focus on individual responsibility is characteristic of a biopolitical mode of governance (Rabinow and Rose, Citation2006; Foucault, Citation1975, notably through his use of “discipline”) that produces the individual body as the object (the target) and the subject of this form of biopower. Strategies and imperatives focusing on the individual’s role with regards to their health shift the attention away from the social and environmental networks within which one’s health is defined and evolves. Not everyone can opt for the so-called “right choices”, those that would purportedly orient or even drive the becoming of one’s health (something that remains, as I argued earlier, also unclear), and these “choices” might have limited impacts upon one’s health, especially when other pathways of disease causation are neglected.

While discussing practices intended to prevent health issues associated with pesticides and chemical contaminants, I have argued that risk assessment is in some ways “disembodied” in that it is not meant to assess the risk of an individual situated in context, who has ingested or who is about to ingest; it rather monitors variations in the population’s bodies (via statistical calculations). There is hence no consideration for what has already permeated or inflected a body and how that may interact with new inputs. In other words, there is no way of preventing or assessing risk for an individual body who endures an accumulation of harmful processes. As I have stressed multiple times throughout the analysis, this is not because of a disingenuous engagement of researchers/risk managers with risk prevention, but rather a manifestation of the limits of existent tools and knowledge, which constrain what knowledge can be developed and acted upon. As Jasanoff (Citation1999) argues, causation analysis is always partial; the thing is that the apparatus they work within acts as if it was not. Rather than a thorough engagement with partiality, unknowns are dealt with by using specific procedures/practices that force them into the logic of objective closure. As long as thresholds are respected, risks are seen as ‘controlled’.

These dynamics also speaks of what this apparatus is ready to accept in terms of letting die. How resources and energy are spent indicates which bodies are taken care of and how. For example, the difference in how both sets of practices deal with risk prevention/control and work with uncertainty in the context of food consumption reveal the neoliberal and biopolitical approach to risk management in contemporary Western food cultures. Individuals are expected to take care of their own health through the adoption of prescribed practices (such as adopting a “healthy” diet) while broader, more systemic, structural, environmental, social pathways of disease causation are not acted upon, or are even rendered invisible through the public and clinical discourses surrounding conditions that are chiefly understood at an individual level, such as diabetes.

While a whole apparatus has been developed to monitor the incidence of diabetes within the population so that preventive programmes and practices could be developed (and hence eventual health care costs minimised), environmental, societal, and structural causes of such health conditions are not equally addressed or investigated. The acknowledgement of limits in how current techniques allow for seizing and acting upon risk in the context of pesticides and chemical contaminants does not prevent their use and spread; it means more ‘letting go’ (that is, letting die) until more knowledge is produced and risk can be better understood, circumscribed, and/or acted upon. From a biopolitical perspective, the logic that this approach follows is one where action is limited to what does not impinge on capitalism. That means that those who cannot afford to buy the “best” possible foods (local, less processed, organic, and the like), or who embody multiple, accumulated forms of harm that interact with new inputs, are left overlooked. Their bodies are rendered invisible among the many bodies that determine statistically what represents a risk that should be acted upon. While I have focused most particularly on what is being ingested or about to be ingested, these reflections could also be extended to the forms of “letting die” accepted when it comes to what permeates the bodies of those who work in the fields/environments where foods are produced, what some researchers have described as “chronic layering” (Saxton, Citation2021); or as referred to in other contexts as slow violence (Davies, Citation2018; Nixon, Citation2011).

Concluding remarks

In this paper, I have looked at how risk is framed, approached, and worked on following Jasanoff’s (Citation1999) songlines of risk as a lens and framework for analysis. In my study, I have brought forward how various risks associated with food ingestion are worked upon through the identification of causation links and attribution of agency, which I have analysed alongside responsibility. Risk related practices are characterised by uncertainty and unknown futures (Adams et al., Citation2009; Jasanoff, Citation1999; Reith, Citation2004). Yet, as I have discussed, the way we deal with these uncertainties is political. At the end of this analysis, I am left with a similar questioning formulated by Nash (Citation2007), who considered it vital to “[…] [question] why so much of contemporary biomedicine is divorced from any study of the larger environment and why individual solutions to disease such as improving one’s diet are quickly institutionalised while other, more difficult social and environmental questions are not even discussed.” (p. 214–215).

As mentioned in the introduction, more than ever, researchers in social sciences as well as in health and environmental sciences pay closer attention to the environmental causes of chronic and non-communicable conditions that are currently associated with diet (such as diabetes). Yet, the apparatus of testing practices set into place to prevent and control risks associated with food ingestion does not reflect this. The last decades of research in epigenetics, on the microbiome, and in endocrinology among other fields reveal how the “very premise of the discrete body is unravelling” (Murphy, Citation2018, p. 115) and how the body cannot and should not “be treated separatee[d] from environmental flows, a point that has been made by critics and scholars of biomedical paradigms” (Guthman & Mansfield, Citation2015, p. 558). Yet risk management approaches at the intersection of foods and bodies still follow a narrow, linear and decontextualised approach to disease causation, health risk, and biological processes.

I hope that this analysis can help shed light on the power relationships that inform the development of risk management practices. I also hope that it can help with fostering better acknowledgement of the role of this risk management apparatus in not only managing risks and health, but also orienting the focus of interventions and hence how (and which) bodies are cared for. Throughout the article, I have highlighted different ways in which the risk, while unevenly distributed, might also be unevenly addressed, despite an appearance of objective and universal treatment of all bodies constitutive of the Canadian population. In other words, the biotechnical apparatus set into place to manage risks can contribute to reinforcing existing inequalities – for instance, through the neglection of pathways of disease causation, through the targeting of certain bodies more than others, through the meanings that are associated with the interpretation of the results created, through the absence of consideration for the specificities of a body situated. In a context where many researchers are seeking to heighten our awareness of the discrimination and stigmatisation that surrounds diabetes in the context of the moral panic created around obesity and “diabesity” (McNaughton, Citation2013a; McNaughton & Smith, Citation2018), this article has intended to contribute to shedding light on how more effort could be invested in transforming our food system and environments so that they would be themselves more healthy and sustainable, especially in a context of increasing recognition of use of pesticides, chemical contaminants and pollution, more generally.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the anonymous reviewers of this manuscript as well as Patrick Brown, the editor of this Journal for their generous comments throughout the reviewing process, which immensely helped improving this paper by clarifying its contribution and key arguments. Thank you also to Emily Yates-Doerr and to the colleagues from the “Origin stories of harm” workshop hosted in Amsterdam in November 2022 who provided insightful comments on the previous version of this manuscript, leading to its improved version. Thank you also to Samuel Thulin who has helped with clarifying the ideas presented in this paper by helping with the editing.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. To situate myself to the reader: I am a White settler francophone Canadian based in Quebec.

2. Hence not practices dedicated to control acute outbreaks.

3. Since it is seen as engaging only “small costs” in comparison to the “burden of illness” for the Canadian society (Canadian Task Force clinical guide for diabetes screening; https://canadiantaskforce.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/2012-type-2-diabetes-clinician-summary-en-1.pdf).

References

- Abrahamsson, S., Bertoni, F., Mol, A., & Ibáñez Martín, R. (2015). Living with omega-3: New materialism and enduring concerns. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 33(1), 4–19. https://doi.org/10.1068/d14086p

- Adams, V., Murphy, M., & Clarke, A. E. (2009). Anticipation: Technoscience, life, affect, temporality. Subjectivity, 28(1), 246–265. https://doi.org/10.1057/sub.2009.18

- Alaimo, S., & Hekman, S. (Eds.). (2008). Material Feminisms. Indiana University Press.

- Bennett, J. A. (2019). Managing diabetes: The cultural politics of disease. NYU Press.

- Berman, R. (2022). Soil pollution: Pesticides, plastics may lead to heart disease. MedicalNewstoday. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/pollution-and-health-contaminated-soil-may-lead-to-heart-disease#Workers-in-the-fields-at-risk

- Bombak, A. E., Riediger, N. D., Bensley, J., Ankomah, S., & Mudryj, A. (2020). A systematic search and critical thematic, narrative review of lifestyle interventions for the prevention and management of diabetes. Critical Public Health, 30(1), 103–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/09581596.2018.1516033

- Bowness, E., James, D., Desmarais, A. A., McIntyre, A., Robin, T., Dring, C., & Wittman, H. (2020). Risk and responsibility in the corporate food regime: Research pathways beyond the COVID-19 crisis. Studies in Political Economy, 101(3), 245–263. https://doi.org/10.1080/07078552.2020.1849986

- Braun, L. (2014). Breathing race into the machine: the surprising career of the spirometer from plantation to genetics. Univ Of Minnesota Press.

- Campos, P. (2011). Does fat kill? a critique of the epidemiological evidence. In E. Rich, L. F. Monaghan, & L. Aphramor (Eds.), Debating Obesity: Critical Perspectives (pp. 36–59). Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Clarke, A., Mamo, L., Fosket, J. R., Fishman, J. R., & Shim, J. K. (2010). Biomedicalization : Technoscience, health, and illness in the U.S. Duke University Press.

- Davies, T. (2018). Toxic space and time: Slow violence, necropolitics, and petrochemical pollution. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 108(6), 1537–1553. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2018.1470924

- Doucet-Battle, J. (2021). Sweetness in the blood: race, risk, and type 2 diabetes. Minnesota University Press.

- Douglas, M. (1992). Risk and Blame Essays in Cultural Theory. Routledge Taylor & Francis.

- Durocher, M. (2023). ‘Healthy’ food and the production of differentiated bodies in ‘anti-obesity’ discourses and practices. Fat Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Body Weight and Society, Fat Food Justice and Fat Femininities, 12(1), 37–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/21604851.2021.1980281

- Durocher, M. (forthcoming). What’s in the Blood? Analyzing Temporalities at Play in Diet-Related Risk Management Testing Practices. Science, Technology, and Human Values.

- Ehlers, N., & Krupar, S. (2019). Deadly Biocultures. University of Minnesota Press.

- Evangelou, E., Ntritsos, G., Chondrogiorgi, M., Kavvoura, F. K., Hernández, A. F., Ntzani, E. E., & Tzoulaki, I. (2016). Exposure to pesticides and diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environment International, 91, 60–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2016.02.013

- Fletcher, I. (2022). Middle-aged businessman and social progress: the links between risk factor research and the obesity epidemic. In M. Gard, D. Powell, & J. Tenorio (Eds.), Routledge handbook of critical obesity studies. Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9780429344824-8/middle-aged-businessman-social-progress-isabel-fletcher

- Foucault, M. (1975). Surveiller et punir: naissance de la prison. Gallimard.

- Frazer, Bianca C., and Heather R. Walker, eds. (2021). (Un)Doing diabetes: representation, disability, culture. In Frazer, B. C., and Walker, H. R. (Eds.), Palgrave studies in science and popular culture (pp. 1–18). Springer International Publishing.

- Gabrielson, T. (2016). The enactment of intention and exception through poisoned corpses and toxic bodies. In V. Pitts-Taylor (Ed.), Mattering: Feminism, Science, and Materialism (pp. 173–187). NYU Press.

- Gálvez, A., Carney, M., & Yates‐Doerr, E. (2020). Chronic disaster: Reimagining noncommunicable chronic disease. American Anthropologist, 122(3), 639–640. https://doi.org/10.1111/aman.13437

- Goldstein, D. M. (2017). Invisible harm: Science, subjectivity and the things we cannot see. Culture, Theory & Critique, 58(4), 321–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/14735784.2017.1365310

- Gravlee, C. C. (2009). How race becomes biology: Embodiment of social inequality. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 139(1), 47–57. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.20983

- Gupta, R., Kumar, P., Fahmi, N., Garg, B., Dutta, S., Sachar, S., Matharu, A. S., & Vimaleswaran, K. S. (2020). Endocrine disruption and obesity: A current review on environmental obesogens. Current Research in Green and Sustainable Chemistry, 3, 100009. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crgsc.2020.06.002

- Guthman, J. (2011). Weighing In: Obesity, food justice, and the limits of capitalism (1st ed.). University of California Press.

- Guthman, J., & Mansfield, B. (2013). The implications of environmental epigenetics: A new direction for geographic inquiry on health, space, and nature-society relations. Progress in Human Geography, 37(4), 486–504. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132512463258

- Guthman, J., & Mansfield, B. (2015). Nature, difference, and the body. In T. Perreault, G. Bridge, & J. McCarthy (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Political Ecology (pp. 558–570). Routledge.

- Harthorn, B. H., & Oaks, L. (2003). Risk, culture, and health inequality: shifting perceptions of danger and blame. ABC-CLIO.

- Hatch, A. R. (2016). Blood sugar. Minnesota University Press.

- Hatch, A. R., Sternlieb, S., & Gordon, J. (2019). Sugar ecologies: Their metabolic and racial effects. Food, Culture & Society, 22(5), 595–607. https://doi.org/10.1080/15528014.2019.1638123

- Health Canada. (2000). Health Canada decision-making framework for identifying, assessing, and managing health risks. [Governmental website]. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/corporate/about-health-canada/reports-publications/health-products-food-branch/health-canada-decision-making-framework-identifying-assessing-managing-health-risks.html

- Health Canada. (2003). Canadian total diet study. Governmental website. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/food-nutrition/food-nutrition-surveillance/canadian-total-diet-study.html

- Health Canada. (2005). Table - food and nutrition surveillance in Canada: an environmental scan. Governmental Website. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/food-nutrition/food-nutrition-surveillance/table-food-nutrition-surveillance-canada-environmental-scan.html

- Health Canada. (2010). Human biomonitoring of environmental chemicals [governmental website]. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/environmental-workplace-health/environmental-contaminants/human-biomonitoring-environmental-chemicals.html

- Henry, E. (2021). Governing occupational exposure using thresholds: A policy biased toward industry. Science, Technology, & Human Values, 46(5), 953–974. https://doi.org/10.1177/01622439211015300

- Hite, A. (2020). A critical perspective on “diet-related” diseases. American Anthropologist, 122(3), 657–658. https://doi.org/10.1111/aman.13446

- Jasanoff, S. (1999). The songlines of risk. Environmental Values, 8(2), 135–152. https://doi.org/10.3197/096327199129341761

- Landecker, H. (2011). Food as exposure: Nutritional epigenetics and the new metabolism. Biosocieties, 6(2), 167–194. https://doi.org/10.1057/biosoc.2011.1

- Langston, N. (2010). Toxic bodies. Yale University Press.

- Liboiron, M. (2021). Pollution is colonialism. Duke University Press.

- Lock, M., & Nguyen, V.-K. (2018). An anthropology of biomedicine (2nd ed.). Wiley-Blackwell.

- Manderson, L., & Warren, N. (2016). “Just one thing after another”: Recursive cascades and chronic conditions. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 30(4), 479–497. https://doi.org/10.1111/maq.12277

- Mary, D., & Wildavsky, A. B. (1983). Risk and culture: an essay on the selection of technical and environmental dangers. 1st pbk. print. University of California Press.

- McCullough, M. B., & Hardin, J. A. (2013). Reconstructing obesity: The meaning of measures and the measure of meanings (First ed.). Berghahn Books.

- McNaughton, D. (2013a). Diabesity” and the stigmatizing of lifestyle in Australia. In M. B. McCullough & J. A. Hardin (Eds.), Reconstructing obesity: The meaning of measures and the measure of meanings (1st ed. Vol. 2, pp. 71–86). Berghahn Books.

- McNaughton, D. (2013b). ‘Diabesity’ down under: Overweight and obesity as cultural signifiers for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Critical Public Health, 23(3), 274–288. https://doi.org/10.1080/09581596.2013.766671

- McNaughton, D., & Smith, C. (2018). Diabesity or the “twin epidemics”: Reflections on the iatrogenic consequences of stigmatising lifestyle to reduce the incidence of diabetes mellitus in Canada. In J. Ellison, D. McPhail, & W. Mitchinson (Eds.), Obesity in Canada: Critical perspectives (pp. 122–147). University of Toronto Press.

- Montoya, M. (2011). Making the Mexican diabetic: Race, science, and the genetics of inequality. University of California Press.

- Moran-Thomas, A. (2020). Traveling with sugar: Chronicles of a global epidemic. University of California Press.

- Murphy, M. (2006). Sick building syndrome and the problem of uncertainty. Duke University Press.

- Murphy, M. (2017). Alterlife and decolonial chemical relations. Cultural Anthropology, 32(4), 494–503. https://doi.org/10.14506/ca32.4.02

- Murphy, M.(2018). Against population, towards afterlife. In A. E. Clarke, & D. Haraway (Eds.), Making kin, not population (pp. 101–124). Prickly Paradigm Press.

- Nash, L. (2007). Inescapable ecologies: A history of environment, disease, and knowledge. University of California Press.

- Neel, B. A., & Sargis, R. M. (2011). The paradox of progress: environmental disruption of metabolism and the diabetes epidemic. Diabetes: Diabetes, 60(7), 1838–1848. https://doi.org/10.2337/db11-0153

- Nixon, R. (2011). Slow violence and the environmentalism of the poor. Harvard University Press.

- O’Donovan, G., & Cadena-Gaitán, C. (2018). Air pollution and diabetes: It’s time to get active! The Lancet Planetary Health, 2(7), e287–e288. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(18)30148-7

- Pitts-Taylor, V. (Ed.). (2016). Mattering: Feminism, science, and materialism. NYU Press.

- Polzer, J., & Power, E. M. (2016). Neoliberal governance and health: duties, risks, and vulnerabilities. McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- Puig de la Bellacasa, M. (2017). Matters of care: Speculative ethics in more than human worlds (1st ed.). Univ Of Minnesota Press.

- Rabinow, P., & Rose, N. (2006). Biopower Today. BioSocieties, 1, 195–217.

- Rabinow, P., & Rose, N. S. (2003). Introduction: Foucault today. In P. Rabinow & N. S. Rose (Eds.), The essential foucault: selections from essential works of foucault, 1954-1984 (pp. vii–xxxv). New Press.

- Reith, G. (2004). Uncertain times: The notion of ‘risk’ and the development of modernity. Time & Society, 13(2–3), 383–402. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961463X04045672

- Roberts, E. F. S. (2021). Making better numbers through bioethnographic collaboration. American Anthropologist, 123(2), 355–369. https://doi.org/10.1111/aman.13560

- Rock, M. (2003). Sweet blood and social suffering: Rethinking cause-effect relationships in diabetes, distress, and duress. Medical Anthropology, 22(2), 131–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/01459740306764

- Rock, M. (2005a). Classifying diabetes; or, commensurating bodies of unequal experience. Public Culture, 17(3), 467–486. https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-17-3-467

- Rock, M. (2005b). Figuring out type 2 diabetes through genetic research: Reckoning kinship and the origins of sickness. Anthropology & Medicine, 12(2), 115–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/13648470500139890

- Saxton, D. I. (2021). The devil’s fruit: farmworkers, health, and environmental justice. Rutgers University Press.

- Sherifali, D. (2011). Screening for type 2 diabetes ( p. 50). McMaster University.

- Shim, J. K. (2002). Understanding the routinised inclusion of race, socioeconomic status and sex in epidemiology: The utility of concepts from technoscience studies. Sociology of Health & Illness, 24(2), 129–150. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.00288

- Villines, Z. (2022). Diabetes and sugar intake: what is the link? MedicalNewstoday. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/317246#summary

- Vogel, S. A. (2013). Is it safe? BPA and the struggle to define the safety of chemicals. University of California Press.