Introduction

Functional neurological disorders (FNDs) are a group of closely related neuropsychiatric conditions that occur frequently (Asadi-Pooya, Citation2021; Stone et al., Citation2009), that cause significant disability and distress in patients (Gelauff et al., Citation2019; Jennum et al., Citation2019), and that have a large public health impact (Asadi-Pooya et al., Citation2021; Stephen et al., Citation2021). FNDs consist of neurological symptoms (e.g., seizures, tremors, memory loss) that are due to neural network dysfunction rather than readily identifiable structural pathology (Aybek & Perez, Citation2022; Bennett et al., Citation2021). The concept of FNDs has undergone a great deal of refinement over time, with a variety of prior labels (e.g., hysteria, wandering uterus, pseudoseizure) being inaccurate and stigmatizing. Most recently, FNDs were conceptualized as a conversion disorder (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2022), a term popularized by Freud to mean that underlying traumatic stress and other mental health symptoms are transformed (or converted) into physical/neurological manifestations (Zepf, Citation2015). While it is widely accepted that psychological distress can indeed impact biological health, including in FNDs (Ertan et al., Citation2022; Hallett et al., Citation2022; Jennum et al., Citation2019), modern day frameworks are broader and more complex than a single mechanism, leading to a shift in terminology from conversion disorder to FNDs. Importantly, emphasizing the functional nature of FNDs is consistent with the preference of many patients, who identify FND as a more neutral and representative term than other diagnostic options (Ding & Kanaan, Citation2016).

FNDs have multifaceted etiologies, diverse presentations, and a wide variety of comorbidities (Baslet et al., Citation2010; Butler et al., Citation2021; Ducroizet et al., Citation2023). Although their core symptoms have been observed for thousands of years and across many different cultures (Edwards et al., Citation2023; Kanemoto et al., Citation2017), they have been widely underrecognized and misunderstood in the era of modern medicine (Keynejad et al., Citation2017; Klinke et al., Citation2021; McWhirter et al., Citation2022; Rawlings & Reuber, Citation2018). This is likely due in large part to an overreliance on conventional medical technologies (e.g., brain MRI, spinal tap, and angiography), which cannot reliably identify/diagnose FNDs. Unfortunately, lack of recognition has prevented many patients with FNDs from receiving adequate care, with providers expressing uncertainty in diagnosis and management, and a great deal of avoidance of responsibility occurring amongst clinicians (Barnett et al., Citation2022; Ducroizet et al., Citation2023; Foley et al., Citation2022).

One particularly prevalent historical misunderstanding in the clinical care of patients with FNDs has been the confusion between FNDs and feigning, factitious disorder, and malingering (Edwards et al., Citation2023). That is, many patients with FNDs have been identified by their providers as faking their symptoms. However, FNDs are distinct from disorders where symptoms are intentionally fabricated in order to achieve a goal (e.g., secondary gain, attention from caregivers or medical providers). Instead, the symptoms in FND patients are genuinely experienced rather than being feigned or malingered and are believed to be due in part to excessive interoceptive monitoring, impairments in the sense of agency, and (sometimes) partial decrements in voluntary bodily control (Drane et al., Citation2021; Hallett et al., Citation2022; Pick et al., Citation2019). In order to address this and other misperceptions, there are ongoing efforts to enhance providers’ general education about FNDs, with the ultimate goal of improving healthcare for these patients (Lehn et al., Citation2020; Medina et al., Citation2021; Milligan et al., Citation2022).

Subtypes and diagnosis

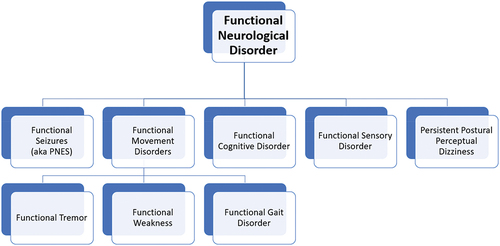

The larger FND umbrella includes a wide variety of sensory, motor, and cognitive symptoms, which can be grouped into subordinate categories (e.g., via DSM 5 specifiers; American Psychiatric Association, Citation2022). Three of the most common FND subtypes with associated cognitive deficits are functional seizures (FS), functional cognitive disorders (FCD), and functional movement disorders (FMDs). In addition to FS, FCD, and FMD, other FND subtypes have been identified, such as functional sensory disorders (Stone & Vermeulen, Citation2016) and persistent postural perceptual dizziness (Espay et al., Citation2018). However, these variations have less empirical support with respect to neurobiology and cognitive functioning and are beyond the scope of this review. shows a simplified breakdown of FND subtypes, while provides a list of additional readings related to FNDs, FS, FCD, and FMD.

Figure 1. A simplified diagram of functional neurological disorder subtypes.

Table 1. Further readings related to FNDs.

The modern day diagnosis of FND subtypes involves the identification of positive signs, which are clinical features that provide evidence for a rule-in determination (Bennett et al., Citation2021; Finkelstein & Popkirov, Citation2023; Silverberg & Rush, Citation2023). For example, FCD is diagnosed based in large part on the presence of internal inconsistency, in which the individual shows observable deficits within a cognitive domain in some situations but not in others (not due to the attentional fluctuations seen in delirium or Lewy body disease; Ball et al., Citation2020; Cabreira, Frostholm, et al., Citation2023; McWhirter et al., Citation2020). FMDs show positive signs of inconsistency/incongruity within the motor domain (Aybek & Perez, Citation2022; Perez, Aybek, et al., Citation2021), while FS is diagnosed based on video EEG evidence of a paroxysmal seizure event that is not linked to epileptiform activity (LaFrance Jr. et al., Citation2013). Overall, well-supported positive signs mean that FNDs are not a diagnosis of exclusion and the determination of FND by an experienced clinician is associated with high diagnostic accuracy and stability over time (i.e., misdiagnosis is rare; Gelauff et al., Citation2019; Stone et al., Citation2005, Citation2009; Walzl et al., Citation2019).

A longstanding debate in neurology, psychiatry, and psychology, relevant to FND subtypes, revolves around the tendency toward “lumping” versus “splitting.” In other words, should the focus of inquiry be on higher order concepts that incorporate many unique components within them (i.e., lumping), or should investigators continually seek to break down multifaceted constructs into simpler, more homogenous ideas (i.e., splitting or reductionism)? This philosophical tension has impacted the development of modern day neuropsychology, including with frameworks for intellectual functioning (e.g., the Cattel-Horn-Carroll [CHC] model; Jewsbury et al., Citation2017) that discuss a hierarchy of cognition, from overall composite scores (full scale IQ; Spearman’s g), to intermediary constructs (e.g., Working Memory Index), to specific subscale scores (e.g., Digit Span scaled score). Psychopathologic nosologies such as the DSM (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2022), the Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP; Kotov et al., Citation2017), and the Research Domain Criteria (RDoC; Insel et al., Citation2010) face similar issues. The lumping versus splitting question, which is clearly not an all-or-nothing endeavor, plays an important role in the understanding of FNDs. For example, there is accumulating evidence for shared biological underpinnings and cognitive profiles across FND subtypes such as FS, FCD, and FMD (Lidstone, Araújo, et al., Citation2020;Hallett et al., Citation2022), arguing for a unified approach to FNDs, while other data suggest unique FND symptom expressions (Ekanayake et al., Citation2017; Kola & LaFaver, Citation2022; Matin et al., Citation2017). Important differences across the subtypes include overt symptoms (FS: seizures, FCD: memory loss, FMD: motor abnormalities), method of diagnosis (FS: video EEG, FCD: neurological or neuropsychological evaluation, FMD: movement disorders examination), and unique treatment approaches (FS: psychotherapy for seizures, FCD: metacognitive training; FMD: physiotherapy).

Ultimately, it is clear that there are important cross-cutting contributors to and characteristics of FNDs that make each subtype closely related to the others (Hallett et al., Citation2022; Kola & LaFaver, Citation2022), and that reinforce the idea of FNDs as a coherent concept. This means that research findings in one FND subtype are likely to generalize well to other subtypes in most situations and that clinicians can talk about FNDs in a general sense with patients. For example, with respect to cognition, it has been argued that a transdiagnostic functional cognitive phenotype (with deficits in selective/divided attention) cuts across FNDs and other related conditions (e.g., fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome; Teodoro et al., Citation2018). On the other hand, the unique aspects of FS, FCD, and FMD argue for continued exploration of specific assessment and treatment strategies that are targeted to the outward expression of the disorder (e.g., the Taking Control of Your Seizures workbook; LaFrance Jr. et al., Citation2014; Reiter et al., Citation2015; Van Patten, Blum et al., Citation2024).

Mental health

Mental health is a core aspect of FNDs and is likely involved in etiology, pathophysiology, symptom manifestations, and treatment outcomes (Ertan et al., Citation2022; Gutkin et al., Citation2021; Hallett et al., Citation2022; Popkirov et al., Citation2019). Comorbid mental health disorders are highly prevalent in FNDs, often occurring at higher rates in FNDs than in other neurological conditions (Cabreira, Frostholm, et al., Citation2023; Walsh et al., Citation2018). For example, with regard to FS, roughly half of patients have depression, half have an anxiety disorder, half have PTSD, and over half have a trauma history (Brown & Reuber, Citation2016a; Popkirov et al., Citation2019), and these comorbidities likely impact cognitive functioning (Ye et al., Citation2020). Although psychiatric symptoms also occur with traditional neurological disorders such as epilepsy, stroke, and TBI, FS can present with a particularly wide range of mental health conditions, including dissociation (Campbell et al., Citation2023), somatization (Fobian & Elliott, Citation2019), and alexithymia (Demartini et al., Citation2014; Sequeira & Silva, Citation2019), among others. Consequently, a thorough assessment of psychopathology is widely appreciated as a core aspect of a comprehensive evaluation of patients with FNDs (Nicholson et al., Citation2020; Pick et al., Citation2020; Saxena et al., Citation2020).

Much of the progress in understanding and treating FNDs in recent years has come as a result of the appreciation of FNDs and their mental health symptoms as brain-based neuropsychiatric conditions. Critically, these disorders are equally real and valid as conventional neurological conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease, TBI, and epilepsy. Rather than imposing a dualistic mind/brain dichotomy in patient interactions, which has been associated with the experience of stigma and limited engagement in care (Ducroizet et al., Citation2023; Foley et al., Citation2022; Rawlings & Reuber, Citation2018), an appreciation for important links between emotions and neurobiology (Pick et al., Citation2019) and communication of a unified mind/brain understanding of FNDs has been suggested as an ideal treatment approach (Finkelstein et al., Citation2022; Gilmour et al., Citation2020; O’Neal et al., Citation2021; Rockliffe-Fidler & Willis, Citation2019; Stone, Citation2016).

Cognitive functioning

There is growing recognition of the centrality of cognition in FNDs (Alluri et al., Citation2020; Butler et al., Citation2021; Carle-Toulemonde et al., Citation2023). For example, cognitive dysfunction is integral to theoretical models of FNDs (Brown & Reuber, Citation2016b; Ertan et al., Citation2022; Teodoro et al., Citation2018) and the neural network abnormalities identified in FNDs impact executive control (Foroughi et al., Citation2020; Pick et al., Citation2019). The resultant cognitive profile in these patients is heterogeneous, with some authors suggesting that deficits in selective and divided attention are a core component of FNDs (Teodoro et al., Citation2018). Clinically, cognitive concerns are common in people with FNDs (Ball et al., Citation2020; Carle-Toulemonde et al., Citation2023; Driver-Dunckley et al., Citation2011; Matin et al., Citation2017; Van Patten, Chan, et al., Citation2024) and correlate with important outcomes such as daily functioning and overall quality of life (Jones et al., Citation2016; Věchetová et al., Citation2018). However, in spite of these findings, neuropsychology has traditionally not been intimately involved in FND research, assessment, and treatment, leading to calls to integrate neuropsychologists more regularly into the care of these patients (Alluri et al., Citation2020; Pick et al., Citation2019, Citation2020; Willment et al., Citation2015).

FS

FS are known by a variety of different labels, including psychogenic epilepsy, dissociative seizures, psychogenic nonepileptic seizures, and others (Kholi & Vercueil, Citation2020). Importantly, of all FND subtypes, FS has the most extensive cognitive literature. Historically, there was interest in investigating cognitive profiles as a potential tool to assist in the differential diagnosis of FS from epilepsy (Cragar et al., Citation2002), but the diffuse and nonspecific cognitive profile in FS does not add incremental utility to the gold standard video EEG diagnosis of seizure disorders (Baslet et al., Citation2021; Van Patten, Austin, et al., Citation2024). Meanwhile, more recent work has highlighted other clinically useful capacities of neuropsychological evaluations in these patients, including identifying and ruling out co-occurring neuropsychiatric conditions, tracking cognition over time, assisting in decisions about participation in cognitively complex tasks (e.g., work, medication management), aiding in treatment planning, and facilitating psychoeducation about brain health during feedback sessions (Alluri et al., Citation2020; Willment et al., Citation2015).

Similar to literature in other clinical populations (e.g., Burmester et al., Citation2016), measures of subjective and objective cognition are only loosely connected in FS, with much stronger relationships between subjective cognition and mental health than between subjective concerns and cognitive test scores (Breier et al., Citation1998; Fargo et al., Citation2004; Ye et al., Citation2020). This subjective/objective discrepancy in cognition and other aspects of health is well appreciated in FNDs such as FS and suggests that both patient report and cognitive test results are needed in order to fully characterize the clinical phenotype (Adewusi et al., Citation2021). Regarding performance-based measures, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis on cognition in FS documented global cognitive composite scores of about 0.6 standard deviations below healthy controls, with significantly worse scores in FS compared to controls on all measured cognitive domains (performance validity, attention, processing speed, language, visuospatial skills, learning/memory, executive functions, social cognition; Van Patten, Austin, et al., Citation2024). In contrast, patients with FS performed slightly better than epilepsy patients in the meta-analysis, with the difference being driven in part by worse language functioning in left temporal lobe epilepsy patients compared to those with FS.

FCD

The overall literature on FCD is less well developed than that of FS and FMD and preliminary diagnostic criteria were only recently published (Ball et al., Citation2020; Kemp et al., Citation2022), with FCD not yet being a recognized DSM-5 subtype of FND (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2022). The current proposed FCD research criteria include internally inconsistent cognitive deficits that lead to distress/functional impairment and that are not better explained by a different disorder. Internal inconsistency is a foundational component of FCD and it is distinct from fluctuating cognition in delirium or dementia with Lewy bodies (Ball, McWhirter, et al., Citation2021). Internal inconsistency allows for the differentiation of FCD from neurodegenerative diseases by requiring that the deficit in a particular cognitive domain be present in some situations but not others (contrasting function and dysfunction), with particularly poor performance when attention is directed toward the task at hand (Ball, McWhirter et al., Citation2021). Similar to FS, internal inconsistency in FCD often manifests with moderate-to-severe cognitive concerns in the patient but more mild deficits on cognitive testing (a subjective/objective discrepancy; Larner, Citation2021). For example, dense amnesia leading to impairment/disability in daily life may be reported by a patient who is able to perform within the expected range on objective tests of verbal memory. Alternatively, severe word finding difficulties may be described and clearly observable during a clinical interview when the provider specifically inquires about language abilities (drawing attention to the problem) but may improve/resolve when the patient is distracted by a conversation about their family pet or favorite sports team. Critically, as mentioned above, these symptoms are not equivalent to feigning (Edwards et al., Citation2023; Kemp et al., Citation2022; Silverberg & Rush, Citation2023), although it is possible for FCD and factitious disorder/malingering to co-occur.

FCD overlaps with but is distinct from subjective cognitive decline (Jessen et al., Citation2014, Citation2020; McWhirter et al., Citation2020), and it appears to be a common and underrecognized condition (Ball et al., Citation2020; McWhirter et al., Citation2022), with one systematic review noting that up to 25% of new referrals to tertiary memory disorder clinics have features that raise concern for FCD (McWhirter et al., Citation2020). Much of the work to date has focused on identifying FCD in older adults who have concerns about a neurodegenerative disease, but who may be better described as having FCD (Ball, McWhirter, et al., Citation2021; Bhome et al., Citation2022; Cabreira, Frostholm, et al., Citation2023; Cabreira, McWhirter, et al., Citation2023; McWhirter et al., Citation2020). However, there is interest in FCD (and/or a “functional cognitive overlay”) in a variety of conditions, including mild TBI (mTBI), long COVID, other FNDs, fibromyalgia, and chronic fatigue syndrome, among others (Silverberg & Rush, Citation2023; Teodoro et al., Citation2018, Citation2023; Walzl et al., Citation2022). In the cognitive aging and dementia space, multiple studies have identified several general characteristics and/or behaviors that tend to differentiate patients with FCD from patients with early Alzheimer’s disease or another degenerative condition. These features of FCD include younger age of onset, more years of education, higher rates of mental health conditions, a greater likelihood of attending medical appointments alone, an absence of the “head turn sign” (turning to a collateral source for assistance in answering questions) and, critically, longer, more detailed responses to clinical interview questions (Alexander et al., Citation2019; Cabreira, Frostholm, et al., Citation2023; McWhirter et al., Citation2020, Citation2022). This last factor may have the greatest clinical utility. Patients with FCD often provide highly specific narrative accounts of cognitive lapses in daily life. In other words, when asked a simple opening inquiry such as, “tell me what you’ve noticed with your thinking and memory,” people with FCD, compared to those with degenerative diseases, tend to speak for much longer (a three-fold difference in one study; McWhirter et al., Citation2022) and to share a wealth of specific details about their cognitive failures. Their core memory circuits are generally intact and they are able to talk through the context of their struggles with cognition in daily life, whereas someone with advancing Alzheimer’s disease, for example, cannot.

Overall, there are at least six ongoing questions and issues in the FCD research space:

The proposed diagnostic criteria have been criticized for neglecting external inconsistency (Silverberg & Rush, Citation2023).

There is debate and uncertainty about the underlying mechanisms leading to FCD (with global metacognition as a notable contender; Bhome et al., Citation2019, Citation2022; Larner, Citation2021).

The possibility of FCD as a dementia prodrome needs further research (Cabreira, Frostholm, et al., Citation2023; Schwilk et al., Citation2021).

The specific role of objective cognitive testing in FCD characterization is not yet well flushed out (Kemp et al., Citation2022; Pennington et al., Citation2019).

The possibility of a functional cognitive “overlay” contributing to FNDs, long COVID, and other conditions requires further investigation (Ball, McWhirter, et al., Citation2021; McWhirter et al., Citation2022; Teodoro et al., Citation2023).

Current treatment options are scarce (Metternich et al., Citation2010; Poole et al., Citation2023).

What is clear is that neuropsychologists can and should play a key role in both scientific and clinical work in this area, with Silverberg and Rush (Citation2023) providing guidance and recommendations for all aspects of neuropsychological evaluations with FCD patients.

FMD

FMDs present with heterogeneous symptoms, including tremor, weakness, dystonia, impaired gait/balance, and (frequently) mixed presentations (Lidstone et al., Citation2022; Perez, Edwards, et al., Citation2021; Saxena et al., Citation2020; Tinazzi et al., Citation2020). FMDs co-occur with traditional movement disorders such as parkinsonism, as well as with other neurological disorders such as cerebrovascular disease and migraine (Carle-Toulemonde et al., Citation2023; Tinazzi et al., Citation2021). Much of the attention in assessment and treatment of FMDs has been on motor functioning, medical history, and mental health, with less of a clear focus on cognition (Perez, Aybek, et al., Citation2021). However, this is beginning to change, with increased recognition of the impact of cognition across all FNDs (Teodoro et al., Citation2018), including FMDs (Alluri et al., Citation2020; Saxena et al., Citation2020).

Direct empirical data have begun to reveal the importance of cognition in FMDs specifically. For example, one international survey study of 1,048 people with FNDs (with the majority reporting functional motor symptoms) documented that 80% of the sample had trouble with memory in everyday life (Butler et al., Citation2021). After fatigue, memory concerns were the most commonly reported issue and tended to overlap strongly with other physical and mental health symptoms, leading the authors to suggest that cognitive symptoms may represent a core aspect of FNDs, including FMD. Additionally, in a study of 61 patients with FMD, participants’ anxiety levels and cognitive concerns were the strongest predictors of health-related quality of life, above and beyond motor symptoms and mental health factors (Věchetová et al., Citation2018). This counterintuitive finding, that cognition explains more variance in quality of life than the presenting problem (movement abnormalities), highlights the heterogeneity and complexity of the FMD phenotype, with the most salient symptom sometimes being a window into additional underlying deficits that affect daily functioning.

The current gold standard treatment for FMDs is interdisciplinary, often involving close collaborations between professionals in neurology, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and psychology (Jacob et al., Citation2018; Lidstone, MacGillivray et al., Citation2020). Although some clinics do regularly refer FMD patients for neuropsychological evaluations (Alluri et al., Citation2020), this is the exception rather than the rule. It is likely that the disorder’s semiology places many of these patients on a different care path than patients with FS or FCD, and cognitive assessment may not be as well integrated into these movement-specific settings. However, results reviewed above about the shared pathophysiology, mechanisms, and symptom expressions across FNDs (Finkelstein & Popkirov, Citation2023; Forejtová et al., Citation2023; Hallett et al., Citation2022; Hopp et al., Citation2012; Lidstone, Araújo, et al., Citation2020; Tinazzi et al., Citation2021), together with some specific evidence for cognitive problems in FMDs (Alluri et al., Citation2020; Butler et al., Citation2021; Věchetová et al., Citation2018), argue for increased involvement of neuropsychologists in this FND subtype.

Summary of contributions

The five contributions to this Special Issue each represent an incremental advancement to the literature on the neuropsychology of FNDs. The manuscripts reflect a range of FND variants, with studies investigating FS (Jungilligens et al. and Drane et al.), FMD and FS (Pick et al.), FCD symptoms post-mTBI (Picon et al.), and mixed FND (de Vroege et al.). The five papers are also diverse in their themes and aims, with areas of focus ranging from documenting objective and subjective cognitive discrepancies, to homing in on metacognition or personality factors as methods for better understanding FND symptomatology, to the clinical benefits of a targeted FND intervention. In the remainder of this section, we further highlight each contribution.

Two of the submissions found that FND (Pick et al.) and mTBI/FCD (Picon et al.) groups had intact objective cognitive test scores and greater subjective cognitive concerns than controls, supporting the notion of a cognitive discrepancy representing internal inconsistency. For example, Pick and colleagues examined multiple domains of cognitive functioning in a mixed FMD/FS sample. Compared to healthy controls (HCs), the FMD/FS group was intact on objective testing, although they reported more daily cognitive concerns than HCs, which were associated with lower subjective ratings of their performance on two cognitive measures and with increased depression, somatization, and dissociation. The FMD/FS group also exhibited shorter reaction times on the anger variant of an emotional bias measure, suggesting hypervigilance to the negative stimuli. Findings add to the prior literature in showing a mismatch between objective and perceived cognitive functioning, with subjective concerns being consistently associated with poor mental health.

Picon and colleagues extend the investigation of internal cognitive inconsistency to the domain of prolonged symptoms following mTBI (sometimes called persistent postconcussive symptoms [PPCS]). They hypothesized that persistent self-reported post-mTBI symptoms in the absence of objective impairment could be a manifestation of FCD or could at least share common perpetuating factors (e.g., metacognition, memory perfectionism) with FCD. Similar to Pick and colleagues, these authors found that an mTBI/FCD group performed similarly to HCs on cognitive testing but reported having more functional memory symptoms than controls. The authors also reported that metacognitive efficiency and memory perfectionism did not distinguish between the groups, but that memory perfectionism was positively correlated with functional memory symptoms in participants with mTBI. Depression and repetitive checking behaviors (which can reinforce negative beliefs about memory failures) were higher in the mTBI group relative to controls and were both associated with more functional memory symptoms. Overall, these findings provide early evidence for phenotypic overlap between PPCS and FCD following mTBI and for low mood, checking behaviors, and memory perfectionism as candidate mechanisms explaining some of the variance in risk for developing prolonged FCD-related symptoms following mTBI.

Furthering this work on potential mechanisms underlying the subjective/objective discrepancy in FNDs, Jungilligens and colleagues specifically investigated correlates of metacognition, which they defined as “the ability to reflect, monitor, and report cognitive processes” (i.e., the accuracy of one’s self-assessment). The authors took the novel approach of testing how metacognition relates to affective arousal and behavioral disinhibition in an FS sample, speculating that these factors could partially explain the emergence of seizures in individuals with FS. To do this, they used emotional go/no-go and metacognitive recognition measures to compare inhibition markers, memory, and metacognition between neutral and affectively valenced (negative-emotional) conditions, given that FS frequently occur in the context of negative effects and can be associated with disinhibition. Results showed that behavioral disinhibition did not differ between task conditions but reaction times were slower and memory and metacognition were better for affectively valenced stimuli, suggesting that negatively charged material reduces information processing speed but improves recall and self-awareness in patients with FS. Relationships were inconsistent between metacognition and a) seizure characteristics and b) mental health factors, with no clear pattern of results.

Next, de Vroege and colleagues incorporate effects of trait-based psychological factors by assessing whether the “Big Five” personality model dimensions (openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism) and/or alexithymia (one’s ability to experience, analyze, and communicate emotions) were associated with cognition in a sample of mixed FND. They found that high conscientiousness correlated with lower planning and high alexithymia correlated with lower verbal memory and lower sustained attention, although these effects became nonsignificant when correcting for multiple comparisons. This could suggest that modest relationships between these preexisting traits and cognitive test scores have low clinical significance, although follow-up replication studies with larger sample sizes are needed to weigh in on this question.

An increased understanding of objective/subjective discrepancies, potential underlying mechanisms, and personality/behavioral correlates of cognitive dysfunction in FNDs all have utility, particularly for assessment and clinical characterization. However, the ultimate goal for clinicians caring for patients with FNDs is to provide support and guidance on a path to symptom reduction and improvement of daily functioning and quality of life. With this in mind, in the final contribution to this Special Issue, Drane and colleagues demonstrated the potential positive effect of a targeted holistic intervention for FNDs. They present a case study of a 59-year-old woman with FS who scored in the invalid range on performance validity tests (PVTs) at baseline and whose performances on cognitive measures were exceptionally low on most tests. They describe the belief amongst some providers that a profile such as this (particularly with multiple invalid scores) suggests that treatment is contraindicated. Nevertheless, the patient subsequently underwent a long-term multimodal intervention program including psychoeducation, couples-based mental health counseling, and individual work incorporating aspects of cognitive behavioral therapy, dialectical behavioral therapy, and acceptance and commitment therapy. She also had psychotropic polypharmacy (including antidepressants, benzodiazepines, an opioid, and an anticonvulsant) gradually reduced under the guidance of a psychiatrist. FS events mostly resolved after approximately 6 months of treatment and she reported feeling more “like her old self” after about 2 years of therapy sessions 1–2 times per week. She underwent a repeat neuropsychological evaluation at age 63, with substantial improvement across most cognitive and behavioral domains, including scores all in the valid range on PVTs. Based on incorporating this case study with a review of the literature, the authors highlight several important considerations for clinicians and researchers. First, patients can earn scores in the invalid range on PVTs for numerous reasons, not solely based on the presence or absence of feigning or low motivation. Second, it is possible to attenuate FS events and improve cognitive functioning in individuals who score in the invalid range on PVTs (i.e., these patients can benefit from treatment). Finally, it is best to treat all potential underlying causes of poor cognition (e.g., unnecessary medications, psychiatric issues/trauma history, poor sleep, substance use, and pain) in a holistic manner in order to minimize the chance of relapse or the onset of new symptoms. Although not all patients and clinics have the capacity to support a long-term multimodal treatment program such as that described by Drane and colleagues, their case study shows preliminary evidence that a resource intensive approach can be effective in patients with complex and severe symptoms. The authors concluded their manuscript with a call for more research investigating evidence-based interventions specific to FNDs.

Conclusions and future directions

A great deal of progress has been made in the understanding and treatment of FNDs in recent years. Given widespread, complex neuropsychiatric symptoms and frequent, disabling cognitive impairments in patients with FNDs, neuropsychologists are well positioned to participate in research and clinical care. This Special Issue presents a cross section of small but meaningful studies advancing assessment and treatment in three FND subtypes: FS, FCD, and FMD. The five published manuscripts from this Special Issue both contribute to the current literature and highlight important gaps for further investigation in large prospective studies. In particular, we recommend that future FND researchers focus their efforts in four areas, which have strong potential to move the field forward:

Compare diverse FND samples to matched comparison participants using comprehensive assessment batteries and measuring a broad cross section of cognitive domains and mental health symptoms.

Further investigate characteristics of candidate mechanisms underlying the subjective/objective cognitive discrepancy (internal inconsistency), which may be ideal targets of treatment.

Examine prevalence and phenotypic variation in functional cognitive symptoms following various neuromedical events and illnesses such as mTBI, COVID-19, and vaccines.

Design and test (via clinical trials) FND-tailored cognitive rehabilitation interventions, including tools and strategies targeting specific cognitive deficits and underlying mechanisms.

With continued involvement of interdisciplinary teams of scientists and clinicians, including neuropsychologists, it is likely that significant advancements will be made in the care of patients with FNDs.

Disclosure statement

R. Van Patten receives funding from VA Providence, RR&D Center for Neurorestoration and Neurotechnology. He engages in profit sharing with the International Neuropsychological Society for Continuing Education proceeds from the Navigating Neuropsychology podcast. He also receives royalties from publication of the book, Becoming a Neuropsychologist: Advice and Guidance for Students and Trainees (Springer, 2021). The research reported/outlined here was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, VISN 1 Career Development Award to R. Van Patten. J. Bellone engages in profit sharing with the International Neuropsychological Society for Continuing Education proceeds from the Navigating Neuropsychology podcast. He also receives royalties from publication of the book, Becoming a Neuropsychologist: Advice and Guidance for Students and Trainees (Springer, 2021).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adewusi, J., Levita, L., Gray, C., & Reuber, M. (2021). Subjective versus objective measures of distress, arousal and symptom burden in patients with functional seizures and other functional neurological symptom disorder presentations: A systematic review. Epilepsy & Behavior Reports, 16, 100502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebr.2021.100502

- Alexander, M., Blackburn, D., & Reuber, M. (2019). Patients’ accounts of memory lapses in interactions between neurologists and patients with functional memory disorders. Sociology of Health & Illness, 41(2), 249–265. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.12819

- Alluri, P. R., Solit, J., Leveroni, C. L., Goldberg, K., Vehar, J. V., Pollak, L. E., Colvin, M. K., & Perez, D. L. (2020). Cognitive complaints in motor functional neurological (conversion) disorders: A focused review and clinical perspective. Cognitive and Behavioral Neurology, 33(2), 77–89. https://doi.org/10.1097/WNN.0000000000000218

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed ed., DSM-5 Text Revision). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787

- Asadi-Pooya, A. A. (2021). Incidence and prevalence of psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (functional seizures): A systematic review and an analytical study. International Journal of Neuroscience, 133(6), 598–603. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207454.2021.1942870

- Asadi-Pooya, A. A., Brigo, F., Tolchin, B., & Valente, K. D. (2021). Functional seizures are not less important than epilepsy. Epilepsy & Behavior Reports, 16, 100495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebr.2021.100495

- Aybek, S., & Perez, D. L. (2022). Diagnosis and management of functional neurological disorder. BMJ: British Medical Journal, o64. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.o64

- Ball, H. A., McWhirter, L., Ballard, C., Bhome, R., Blackburn, D. J., Edwards, M. J., Fleming, S. M., Fox, N. C., Howard, R., Huntley, J., Isaacs, J. D., Larner, A. J., Nicholson, T. R., Pennington, C. M., Poole, N., Price, G., Price, J. P., Reuber, M., Ritchie, C. … Carson, A. J. (2020). Functional cognitive disorder: Dementia’s blind spot. Brain A Journal of Neurology, 143(10), 2895–2903. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awaa224

- Ball, H. A., McWhirter, L., Ballard, C., Bhome, R., Blackburn, D. J., Edwards, M. J., Fox, N. C., Howard, R., Huntley, J., Isaacs, J. D., Larner, A. J., Nicholson, T. R., Pennington, C. M., Poole, N., Price, G., Price, J. P., Reuber, M., Ritchie, C., Rossor, M. N. … Carson, A. J. (2021). Reply: Functional cognitive disorder: Dementia’s blind spot. Brain A Journal of Neurology, 144(9), e73. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awab305

- Ball, H. A., Swirski, M., Newson, M., Coulthard, E. J., & Pennington, C. M. (2021). Differentiating functional cognitive disorder from early neurodegeneration: A clinic-based study. Brain Sciences, 11(6), 800. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11060800

- Barnett, C., Davis, R., Mitchell, C., & Tyson, S. (2022). The vicious cycle of functional neurological disorders: A synthesis of healthcare professionals’ views on working with patients with functional neurological disorder. Disability and Rehabilitation, 44(10), 1802–1811. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2020.1822935

- Baslet, G., Bajestan, S. N., Aybek, S., Modirrousta, M., Price, J., Cavanna, A., Perez, D. L., Lazarow, S. S., Raynor, G., Voon, V., Ducharme, S., & LaFrance, W. C. (2021). Evidence-based practice for the clinical assessment of psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: A report from the American neuropsychiatric association committee on research. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 33(1), 27–42. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.neuropsych.19120354

- Baslet, G., Roiko, A., & Prensky, E. (2010). Heterogeneity in psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: Understanding the role of psychiatric and neurological factors. Epilepsy & Behavior, 17(2), 236–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2009.12.008

- Bennett, K., Diamond, C., Hoeritzauer, I., Gardiner, P., McWhirter, L., Carson, A., & Stone, J. (2021). A practical review of Functional Neurological Disorder (FND) for the general physician. Clinical Medicine, 21(1), 28–36. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmed.2020-0987

- Bhome, R., Huntley, J. D., Price, G., & Howard, R. J. (2019). Clinical presentation and neuropsychological profiles of functional cognitive disorder patients with and without co-morbid depression. Cognitive Neuropsychiatry, 24(2), 152–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/13546805.2019.1590190

- Bhome, R., McWilliams, A., Price, G., Poole, N. A., Howard, R. J., Fleming, S. M., & Huntley, J. D. (2022). Metacognition in functional cognitive disorder. Brain Communications, 4(2), fcac041. https://doi.org/10.1093/braincomms/fcac041

- Breier, J. I., Fuchs, K. L., Brookshire, B. L., Wheless, J., Thomas, A. B., Constantinou, J., & Willmore, L. J. (1998). Quality of life perception in patients with intractable epilepsy or pseudoseizures. Archives of Neurology, 55(5), 660. https://doi.org/10.1001/archneur.55.5.660

- Brown, R. J., & Reuber, M. (2016a). Psychological and psychiatric aspects of Psychogenic Non-Epileptic Seizures (PNES): A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 45, 157–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2016.01.003

- Brown, R. J., & Reuber, M. (2016b). Towards an integrative theory of Psychogenic Non-Epileptic Seizures (PNES). Clinical Psychology Review, 47, 55–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2016.06.003

- Burmester, B., Leathem, J., & Merrick, P. (2016). Subjective cognitive complaints and objective cognitive function in aging: A systematic review and meta-analysis of recent cross-sectional findings. Neuropsychology Review, 26(4), 376–393. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11065-016-9332-2

- Butler, M., Shipston‐Sharman, O., Seynaeve, M., Bao, J., Pick, S., Bradley‐Westguard, A., Ilola, E., Mildon, B., Golder, D., Rucker, J., Stone, J., & Nicholson, T. (2021). International online survey of 1048 individuals with functional neurological disorder. European Journal of Neurology, 28(11), 3591–3602. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.15018

- Cabreira, V., Frostholm, L., McWhirter, L., Stone, J., & Carson, A. (2023). Clinical signs in functional cognitive disorders: A systematic review and diagnostic meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 173, 111447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2023.111447

- Cabreira, V., McWhirter, L., & Carson, A. (2023). Functional cognitive disorder. Neurologic Clinics, 41(4), 619–633. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ncl.2023.02.004

- Campbell, M. C., Smakowski, A., Rojas-Aguiluz, M., Goldstein, L. H., Cardeña, E., Nicholson, T. R., Reinders, A. A. T. S., & Pick, S. (2023). Dissociation and its biological and clinical associations in functional neurological disorder: Systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Psychiatry Open, 9(1), e2. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2022.597

- Carle-Toulemonde, G., Goutte, J., Do-Quang-Cantagrel, N., Mouchabac, S., Joly, C., & Garcin, B. (2023). Overall comorbidities in functional neurological disorder: A narrative review. L’Encéphale, 49(4), S24–S32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.encep.2023.06.004

- Cragar, D. E., Berry, D. T. R., Fakhoury, T. A., Cibula, J. E., & Schmitt, F. A. (2002). A review of diagnostic techniques in the differential diagnosis of epileptic and nonepileptic seizures. Neuropsychology Review, 12(1), 31–64. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015491123070

- Demartini, B., Petrochilos, P., Ricciardi, L., Price, G., Edwards, M. J., & Joyce, E. (2014). The role of alexithymia in the development of functional motor symptoms (conversion disorder). Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 85(10), 1062–1062. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2013-307203

- Ding, J. M., & Kanaan, R. A. A. (2016). What should we say to patients with unexplained neurological symptoms? How explanation affects offence. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 91, 55–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2016.10.012

- Drane, D. L., Fani, N., Hallett, M., Khalsa, S. S., Perez, D. L., & Roberts, N. A. (2021). A framework for understanding the pathophysiology of functional neurological disorder. CNS Spectrums, 26(6), 555–561. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1092852920001789

- Driver-Dunckley, E., Stonnington, C. M., Locke, D. E. C., & Noe, K. (2011). Comparison of psychogenic movement disorders and psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: Is phenotype clinically important? Psychosomatics, 52(4), 337–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psym.2011.01.008

- Ducroizet, A., Zimianti, I., Golder, D., Hearne, K., Edwards, M., Nielsen, G., & Coebergh, J. (2023). Functional neurological disorder: Clinical manifestations and comorbidities; An online survey. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience, 110, 116–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2023.02.014

- Edwards, M. J., Yogarajah, M., & Stone, J. (2023). Why functional neurological disorder is not feigning or malingering. Nature Reviews Neurology, 19(4), 246–256. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-022-00765-z

- Ekanayake, V., Kranick, S., LaFaver, K., Naz, A., Frank Webb, A., LaFrance, W. C., Hallett, M., & Voon, V. (2017). Personality traits in Psychogenic Nonepileptic Seizures (PNES) and Psychogenic Movement Disorder (PMD): Neuroticism and perfectionism. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 97, 23–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2017.03.018

- Ertan, D., Aybek, S., LaFrance, W. C., Jr., Kanemoto, K., Tarrada, A., Maillard, L., El-Hage, W., & Hingray, C. (2022). Functional (psychogenic non-epileptic/dissociative) seizures: Why and how? Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 93(2), 144–157. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2021-326708

- Espay, A. J., Aybek, S., Carson, A., Edwards, M. J., Goldstein, L. H., Hallett, M., LaFaver, K., LaFrance, W. C., Lang, A. E., Nicholson, T., Nielsen, G., Reuber, M., Voon, V., Stone, J., & Morgante, F. (2018). Current concepts in diagnosis and treatment of functional neurological disorders. JAMA Neurology, 75(9), 1132. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.1264

- Fargo, J. D., Schefft, B. K., Szaflarski, J. P., Dulay, M. F., Marc Testa, S., Privitera, M. D., & Yeh, H.-S. (2004). Accuracy of self-reported neuropsychological functioning in individuals with epileptic or psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Epilepsy & Behavior, 5(2), 143–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2003.11.023

- Finkelstein, S. A., Adams, C., Tuttle, M., Saxena, A., & Perez, D. L. (2022). Neuropsychiatric treatment approaches for functional neurological disorder: A how to guide. Seminars in Neurology, 42(2), 204–224. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0042-1742773

- Finkelstein, S. A., & Popkirov, S. (2023). Functional neurological disorder: Diagnostic pitfalls and differential diagnostic considerations. Neurologic Clinics, 41(4), 665–679. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ncl.2023.04.001

- Fobian, A. D., & Elliott, L. (2019). A review of functional neurological symptom disorder etiology and the integrated etiological summary model. Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience, 44(1), 8–18. https://doi.org/10.1503/jpn.170190

- Foley, C., Kirkby, A., & Eccles, F. J. R. (2022). A meta-ethnographic synthesis of the experiences of stigma amongst people with functional neurological disorder. Disability and Rehabilitation, 46(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2022.2155714

- Forejtová, Z., Serranová, T., Sieger, T., Slovák, M., Nováková, L., Věchetová, G., Růžička, E., & Edwards, M. J. (2023). The complex syndrome of functional neurological disorder. Psychological Medicine, 53(7), 3157–3167. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291721005225

- Foroughi, A. A., Nazeri, M., & Asadi-Pooya, A. A. (2020). Brain connectivity abnormalities in patients with functional (psychogenic nonepileptic) seizures: A systematic review. Seizure, 81, 269–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seizure.2020.08.024

- Gelauff, J. M., Carson, A., Ludwig, L., Tijssen, M. A. J., & Stone, J. (2019). The prognosis of functional limb weakness: A 14-year case-control study. Brain A Journal of Neurology, 142(7), 2137–2148. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awz138

- Gilmour, G. S., Nielsen, G., Teodoro, T., Yogarajah, M., Coebergh, J. A., Dilley, M. D., Martino, D., & Edwards, M. J. (2020). Management of functional neurological disorder. Journal of Neurology, 267(7), 2164–2172. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-020-09772-w

- Gutkin, M., McLean, L., Brown, R., & Kanaan, R. A. (2021). Systematic review of psychotherapy for adults with functional neurological disorder. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 92(1), 36–44. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2019-321926

- Hallett, M., Aybek, S., Dworetzky, B. A., McWhirter, L., Staab, J. P., & Stone, J. (2022). Functional neurological disorder: New subtypes and shared mechanisms. The Lancet Neurology, 21(6), 537–550. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(21)00422-1

- Hopp, J. L., Anderson, K. E., Krumholz, A., Gruber-Baldini, A. L., & Shulman, L. M. (2012). Psychogenic seizures and psychogenic movement disorders: Are they the same patients? Epilepsy & Behavior, 25(4), 666–669. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2012.10.007

- Insel, T., Cuthbert, B., Garvey, M., Heinssen, R., Pine, D. S., Quinn, K., Sanislow, C., & Wang, P. (2010). Research Domain Criteria (RDoC): Toward a new classification framework for research on mental disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 167(7), 748–751. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09091379

- Jacob, A. E., Smith, C. A., Jablonski, M. E., Roach, A. R., Paper, K. M., Kaelin, D. L., Stretz-Thurmond, D., & LaFaver, K. (2018). Multidisciplinary clinic for Functional Movement Disorders (FMD): 1-year experience from a single centre. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 89(9), 1011–1012. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2017-316523

- Jennum, P., Ibsen, R., & Kjellberg, J. (2019). Morbidity and mortality of Non Epileptic Seizures (NES): A controlled national study. Epilepsy & Behavior, 96, 229–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2019.03.016

- Jessen, F., Amariglio, R. E., Buckley, R. F., Wagner, O., Saykin, A. J., Sikkes, S. A. M., Smart, C. M., Wolfsgruber, S., & Rodriguez-Gomez, M. (2020). The characterisation of subjective cognitive decline. 19(3), 271–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30368-0

- Jessen, F., Amariglio, R. E., Van Boxtel, M., Breteler, M., Ceccaldi, M., Chételat, G., Dubois, B., Dufouil, C., Ellis, K. A., Van Der Flier, W. M., Glodzik, L., Van Harten, A. C., De Leon, M. J., McHugh, P., Mielke, M. M., Molinuevo, J. L., Mosconi, L., Osorio, R. S., Perrotin, A., & Subjective Cognitive Decline Initiative (SCD‐I) Working Group. (2014). A conceptual framework for research on subjective cognitive decline in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 10(6), 844–852.

- Jewsbury, P. A., Bowden, S. C., & Duff, K. (2017). The Cattell–Horn–carroll model of cognition for clinical assessment. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 35(6), 547–567. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734282916651360

- Jones, B., Reuber, M., & Norman, P. (2016). Correlates of health‐related quality of life in adults with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: A systematic review. Epilepsia, 57(2), 171–181. https://doi.org/10.1111/epi.13268

- Kanemoto, K., LaFrance, W., Duncan, R., Gigineishvili, D., Park, S.-P., Tadokoro, Y., Ikeda, H., Paul, R., Zhou, D., Taniguchi, G., Kerr, M., Oshima, T., Jin, K., & Reuber, M. (2017). PNES around the world: Where we are now and how we can close the diagnosis and treatment gaps-an ILAE PNES task force report. Epilepsia Open, 2(3), 307–316. https://doi.org/10.1002/epi4.12060

- Kemp, S., Kapur, N., Graham, C. D., & Reuber, M. (2022). Functional cognitive disorder: Differential diagnosis of common clinical presentations. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 37(6), 1158–1176. https://doi.org/10.1093/arclin/acac020

- Keynejad, R. C., Carson, A. J., David, A. S., & Nicholson, T. R. (2017). Functional neurological disorder: Psychiatry’s blind spot. The Lancet Psychiatry, 4(3), e2–e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30036-6

- Kholi, H., & Vercueil, L. (2020). Emergency room diagnoses of psychogenic nonepileptic seizures with psychogenic status and functional (psychogenic) symptoms: Whopping. Epilepsy & Behavior, 104, 106882. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2019.106882

- Klinke, M. E., Hjartardóttir, T. E., Hauksdóttir, A., Jónsdóttir, H., Hjaltason, H., & Andrésdóttir, G. T. (2021). Moving from stigmatization toward competent interdisciplinary care of patients with functional neurological disorders: Focus group interviews. Disability and Rehabilitation, 43(9), 1237–1246. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2019.1661037

- Kola, S., & LaFaver, K. (2022). Functional movement disorder and functional seizures: What have we learned from different subtypes of functional neurological disorders? Epilepsy & Behavior Reports, 18, 100510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebr.2021.100510

- Kotov, R., Krueger, R. F., Watson, D., Achenbach, T. M., Althoff, R. R., Bagby, R. M., Brown, T. A., Carpenter, W. T., Caspi, A., Clark, L. A., Eaton, N. R., Forbes, M. K., Forbush, K. T., Goldberg, D., Hasin, D., Hyman, S. E., Ivanova, M. Y., Lynam, D. R., Markon, K. … Zimmerman, M. (2017). The Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP): A dimensional alternative to traditional nosologies. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 126(4), 454–477. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000258

- LaFrance, W., Jr., Baird, G. L., Barry, J. J., Blum, A. S., Webb, A., Keitner, G. I., Machan, J. T., Miller, I., & Szaflarski, J. P. (2014). Multicenter pilot treatment trial for psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 71(9), 997–1005. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.817

- LaFrance, W. C., Baker, G. A., Duncan, R., Goldstein, L. H., & Reuber, M. (2013). Minimum requirements for the diagnosis of psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: A staged approach: A report from the international league against epilepsy nonepileptic seizures task force. Epilepsia, 54(11), 2005–2018. https://doi.org/10.1111/epi.12356

- Larner, A. J. (2021). Functional cognitive disorders (FCD): How is metacognition involved? Brain Sciences, 11(8), 1082. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11081082

- Lehn, A., Navaratnam, D., Broughton, M., Cheah, V., Fenton, A., Harm, K., Owen, D., & Pun, P. (2020). Functional neurological disorders: Effective teaching for health professionals. BMJ Neurology Open, 2(1), e000065. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjno-2020-000065

- Lidstone, S. C., Araújo, R., Stone, J., & Bloem, B. R. (2020). Ten myths about functional neurological disorder. European Journal of Neurology, 27(11). https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.14310

- Lidstone, S. C., Costa-Parke, M., Robinson, E. J., Ercoli, T., & Stone, J. (2022). Functional movement disorder gender, age and phenotype study: A systematic review and individual patient meta-analysis of 4905 cases. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 93(6), 609–616. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2021-328462

- Lidstone, S. C., MacGillivray, L., & Lang, A. E. (2020). Integrated therapy for functional movement disorders: Time for a change. Movement Disorders Clinical Practice, 7(2), 169–174. https://doi.org/10.1002/mdc3.12888

- Matin, N., Young, S. S., Williams, B., LaFrance, W. C., King, J. N., Caplan, D., Chemali, Z., Weilburg, J. B., Dickerson, B. C., & Perez, D. L. (2017). Neuropsychiatric associations with gender, illness duration, work disability, and motor subtype in a U.S. Functional neurological disorders clinic population. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 29(4), 375–382. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.neuropsych.16110302

- McWhirter, L., Ritchie, C., Stone, J., & Carson, A. (2020). Functional cognitive disorders: A systematic review. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(2), 191–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30405-5

- McWhirter, L., Ritchie, C., Stone, J., & Carson, A. (2022). Identifying functional cognitive disorder: A proposed diagnostic risk model. CNS Spectrums, 27(6), 754–763. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1092852921000845

- Medina, M., Giambarberi, L., Lazarow, S. S., Lockman, J., Faridi, N., Hooshmad, F., Karasov, A., & Bajestan, S. N. (2021). Using patient-centered clinical neuroscience to deliver the diagnosis of Functional Neurological Disorder (FND): Results from an innovative educational workshop. Academic Psychiatry, 45(2), 185–189. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-020-01324-8

- Metternich, B., Schmidtke, K., Harter, M., Dykierek, P., & Hull, M. (2010). Konzeption und Erprobung eines gruppentherapeutischen Behandlungskonzepts für die funktionelle Gedächtnis- und Konzentrationsstörung. Psychotherapie, Psychosomatik, Medizinische Psychologie, 60(6), 202–210. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0028-1103281

- Milligan, T. A., Yun, A., LaFrance Jr, W. C., Jr., Baslet, G., Tolchin, B., Szaflarski, J., Wong, V. S. S., Plioplys, S., & Dworetzky, B. A. (2022). Neurology residents’ education in functional seizures. Epilepsy & Behavior Reports, 18, 100517. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebr.2021.100517

- Nicholson, T. R., Carson, A., Edwards, M. J., Goldstein, L. H., Hallett, M., Mildon, B., Nielsen, G., Nicholson, C., Perez, D. L., Pick, S., Stone, J., the FND-COM (Functional Neurological Disorders Core Outcome Measures) Group, Anderson, D., Asadi-Pooya, A., Aybek, S., Baslet, G., Bloem, B. R., Brown, R. J. … the FND-COM (Functional Neurological Disorders Core Outcome Measures) Group. (2020). Outcome measures for functional neurological disorder: A review of the theoretical complexities. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 32(1), 33–42.

- O’Neal, M. A., Dworetzky, B. A., & Baslet, G. (2021). Functional neurological disorder: Engaging patients in treatment. Epilepsy & Behavior Reports, 16, 100499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebr.2021.100499

- Pennington, C., Ball, H., & Swirski, M. (2019). Functional cognitive disorder: Diagnostic challenges and future directions. Diagnostics, 9(4), 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics9040131

- Perez, D. L., Aybek, S., Popkirov, S., Kozlowska, K., Stephen, C. D., Anderson, J., Shura, R., Ducharme, S., Carson, A., Hallett, M., Nicholson, T. R., Stone, J., LaFrance, W. C., Voon, V., & (On behalf of the American Neuropsychiatric Association Committee for Research). (2021). A review and expert opinion on the neuropsychiatric assessment of motor functional neurological disorders. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 33(1), 14–26.

- Perez, D. L., Edwards, M. J., Nielsen, G., Kozlowska, K., Hallett, M., & LaFrance Jr, W. C., Jr. (2021). Decade of progress in motor functional neurological disorder: Continuing the momentum. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 92(6), 668–677. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2020-323953

- Pick, S., Anderson, D. G., Asadi-Pooya, A. A., Aybek, S., Baslet, G., Bloem, B. R., Bradley-Westguard, A., Brown, R. J., Carson, A. J., Chalder, T., Damianova, M., David, A. S., Edwards, M. J., Epstein, S. A., Espay, A. J., Garcin, B., Goldstein, L. H., Hallett, M., Jankovic, J. … Nicholson, T. R. (2020). Outcome measurement in functional neurological disorder: A systematic review and recommendations. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 91(6), 638–649. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2019-322180

- Pick, S., Goldstein, L. H., Perez, D. L., & Nicholson, T. R. (2019). Emotional processing in functional neurological disorder: A review, biopsychosocial model and research agenda. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 90(6), 704–711. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2018-319201

- Poole, N., Cope, S., Vanzan, S., Duffus, A., Mantovani, N., Smith, J., Barrett, B. M., Tokley, M., Scicluna, M., Beardmore, S., Turner, K., Edwards, M., & Howard, R. (2023). Feasibility randomised controlled trial of online group Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Functional Cognitive Disorder (ACT4FCD). BMJ Open, 13(5), e072366. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2023-072366

- Popkirov, S., Asadi-Pooya, A. A., Duncan, R., Gigineishvili, D., Hingray, C., Kanner, A. M., LaFrance, C. W., Pretorius, C., & Reuber, M. (2019). The aetiology of psychogenic non‐epileptic seizures: Risk factors and comorbidities. Epileptic Disorders: International Epilepsy Journal with Videotape, 21(6), 529–547. https://doi.org/10.1684/epd.2019.1107

- Rawlings, G. H., & Reuber, M. (2018). Health care practitioners’ perceptions of psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: A systematic review of qualitative and quantitative studies. Epilepsia, 59(6), 1109–1123. https://doi.org/10.1111/epi.14189

- Reiter, J. W., Andrews, D., Reiter, C., & LaFrance, W. C. (2015). Taking control of your seizures. Oxford University Press.

- Rockliffe-Fidler, C., & Willis, M. (2019). Explaining dissociative seizures: A neuropsychological perspective. Practical Neurology, 19(3), 259–263. https://doi.org/10.1136/practneurol-2018-002100

- Saxena, A., Godena, E., Maggio, J., & Perez, D. L. (2020). Towards an outpatient model of care for motor functional neurological disorders: A neuropsychiatric perspective. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 16, 2119–2134. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S247119

- Schwilk, N., Klöppel, S., Schmidtke, K., & Metternich, B. (2021). Functional cognitive disorder in subjective cognitive decline—A 10‐year follow‐up. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 36(5), 677–683. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.5466

- Sequeira, A. S., & Silva, B. (2019). A comparison among the prevalence of Alexithymia in patients with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures, epilepsy, and the healthy population: A systematic review of the literature. Psychosomatics, 60(3), 238–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psym.2019.02.005

- Silverberg, N. D., & Rush, B. K. (2023). Neuropsychological evaluation of functional cognitive disorder: A narrative review. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2023.2228527

- Stephen, C. D., Fung, V., Lungu, C. I., & Espay, A. J. (2021). Assessment of emergency department and inpatient use and costs in adult and pediatric functional neurological disorders. JAMA Neurology, 78(1), 88. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.3753

- Stone, J. (2016). Functional neurological disorders: The neurological assessment as treatment. Practical Neurology, 16(1), 7–17. https://doi.org/10.1136/practneurol-2015-001241

- Stone, J., Carson, A., Duncan, R., Coleman, R., Roberts, R., Warlow, C., Hibberd, C., Murray, G., Cull, R., Pelosi, A., Cavanagh, J., Matthews, K., Goldbeck, R., Smyth, R., Walker, J., MacMahon, A. D., & Sharpe, M. (2009). Symptoms ‘unexplained by organic disease’ in 1144 new neurology out-patients: How often does the diagnosis change at follow-up? Brain A Journal of Neurology, 132(10), 2878–2888. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awp220

- Stone, J., Smyth, R., Carson, A., Lewis, S., Prescott, R., Warlow, C., & Sharpe, M. (2005). Systematic review of misdiagnosis of conversion symptoms and “hysteria. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 331(7523), 989. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.38628.466898.55

- Stone, J., & Vermeulen, M. (2016). Functional sensory symptoms. In Handbook of clinical neurology (Vol. 139, pp. 271–281). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-801772-2.00024-2

- Teodoro, T., Chen, J., Gelauff, J., & Edwards, M. J. (2023). Functional neurological disorder in people with long COVID: A systematic review. European Journal of Neurology, 30(5), 1505–1514. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.15721

- Teodoro, T., Edwards, M. J., & Isaacs, J. D. (2018). A unifying theory for cognitive abnormalities in functional neurological disorders, fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome: Systematic review. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 89(12), 1308–1319. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2017-317823

- Tinazzi, M., Geroin, C., Erro, R., Marcuzzo, E., Cuoco, S., Ceravolo, R., Mazzucchi, S., Pilotto, A., Padovani, A., Romito, L. M., Eleopra, R., Zappia, M., Nicoletti, A., Dallocchio, C., Arbasino, C., Bono, F., Pascarella, A., Demartini, B., Gambini, O. … Morgante, F. (2021). Functional motor disorders associated with other neurological diseases: Beyond the boundaries of “organic” neurology. European Journal of Neurology, 28(5), 1752–1758. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.14674

- Tinazzi, M., Morgante, F., Marcuzzo, E., Erro, R., Barone, P., Ceravolo, R., Mazzucchi, S., Pilotto, A., Padovani, A., Romito, L. M., Eleopra, R., Zappia, M., Nicoletti, A., Dallocchio, C., Arbasino, C., Bono, F., Pascarella, A., Demartini, B., Gambini, O. … Geroin, C. (2020). Clinical correlates of functional motor disorders: An Italian multicenter study. Movement Disorders Clinical Practice, 7(8), 920–929. https://doi.org/10.1002/mdc3.13077

- Van Patten, R., Austin, T., Cotton, E., Chan, L., Bellone, J., Mordecai, K., Altalib, H., Correia, S., Twamley, E., Jones, R., Sawyer, K., & LaFrance, W., Jr. (2024). Cognitive performance in functional seizures compared to epilepsy and healthy controls: A systematic review and meta analysis. Under Review.

- Van Patten, R., Blum, A., Correia, S., Philip, N., Allendorfer, J., Gaston, T., Goodman, A., & Grayson, L. (2024). Neurobehavioral therapy in seizures with TBI: A non-randomized controlled trial. Under Review.

- Van Patten, R., Chan, L., Tocco, K., Mordecai, K., Altalib, H., Cotton, E., Correia, S., Gaston, T., Grayson, L., Martin, A., Fry, S., Goodman, A., Allendorfer, J., Szaflarski, J., & LaFrance, W., Jr. (2024). Reduced subjective cognitive concerns with neurobehavioral therapy in functional seizures and traumatic brain injury. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences.

- Věchetová, G., Slovak, M., Kemlink, D., Hanzlikova, Z., Dusek, P., Nikolai, T., Ruzicka, E., Edwards, M. J., & Serranova, T. (2018). The impact of non-motor symptoms on the health-related quality of life in patients with functional movement disorders. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 115, 32–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2018.10.001

- Walsh, S., Levita, L., & Reuber, M. (2018). Comorbid depression and associated factors in PNES versus epilepsy: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Seizure, 60, 44–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seizure.2018.05.014

- Walzl, D., Carson, A. J., & Stone, J. (2019). The misdiagnosis of functional disorders as other neurological conditions. Journal of Neurology, 266(8), 2018–2026. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-019-09356-3

- Walzl, D., Solomon, A. J., & Stone, J. (2022). Functional neurological disorder and multiple sclerosis: A systematic review of misdiagnosis and clinical overlap. Journal of Neurology, 269(2), 654–663. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-021-10436-6

- Willment, K., Hill, M., Baslet, G., & Loring, D. W. (2015). Cognitive impairment and evaluation in psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: An integrated cognitive-emotional approach. Clinical EEG and Neuroscience, 46(1), 42–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/1550059414566881

- Ye, K., Foster, E., Johnstone, B., Carney, P., Velakoulis, D., O’Brien, T. J., Malpas, C. B., & Kwan, P. (2020). Factors associated with subjective cognitive function in epilepsy and psychogenic non-epileptic seizures. Epilepsy Research, 163, 106342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2020.106342

- Zepf, S. (2015). Some notes on Freud’s concept of conversion. International Forum of Psychoanalysis, 24(2), 77–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/0803706X.2013.765066