ABSTRACT

Objective

Prior work has demonstrated that women have been historically underrepresented across various research fields, including neuropsychology. Given these disparities, the goal of this study was to systematically evaluate the inclusion of women as participants in neuropsychology research. The current study builds upon previous research by examining articles from eight peer-reviewed neuropsychology journals published in 2019.

Method

Empirical articles examining human samples were included in the current review if they were available in English. Eligible articles were examined to glean whether the main topic of the article was related to a gender issue, how gender was categorized, the gender distribution of the sample, whether gender was considered in analyses, whether gender was addressed in the discussion, and what age categories the study examined.

Results

There was a relatively even distribution of men (51.76%) and women (48.24%) in neuropsychological research studies reviewed. There were twice as many studies that included only men compared to only women (16 vs. 8 studies), and nearly twice as many studies consisted of ≥ 75% men (16.6%) compared to ≥75% of women (8.5%). Gender-focused research was limited (3%). Furthermore, gender was frequently disregarded in analyses (58%) and often not addressed in the discussion (75%).

Conclusions

The current study highlights the limitations within neuropsychology related to the representation of women in research. Although it is encouraging that neuropsychological research is generally inclusive of women participants, future research should aim to more comprehensively investigate how gender may influence cognitive risk and resilience factors across different clinical presentations. Recommendations to begin addressing this challenge and to move toward more gender-equitable research are provided.

Introduction

Females and womenFootnote1 are historically underrepresented across various research fields, spanning animal models, human subjects studies, basic science, and clinical trials (Feldman, Citation2019; Will et al., Citation2017). Within the field of neuroscience, biases in sex and genderFootnote2 inclusion are particularly prevalent (Shansky & Woolley, Citation2016). The term “sex omission” has been used to describe a lack of reporting on sex in research articles (Will et al., Citation2017). In fact, a 2011 study examining ten biological disciplines revealed that neuroscience had the most considerable sex bias, both in terms of the proportion of men to women included in studies and appropriate reporting of sex data (Beery & Zucker, Citation2011). Even in studies that do include equal representations of men and women, sex is often omitted from analyses and discussion, thereby limiting our understanding of its potential impact on outcomes (Will et al., Citation2017). Demonstrating the extent of this problem, a 2020 study of six major neuroscience journals revealed that 73% of human participant studies did not consider the role of biological sex in their analyses (Mamlouk et al., Citation2020). As such, there is a pressing need to address the sex bias present in neuroscience research and promote more inclusive practices.

Clinically, these pervasive patterns of sex bias and omission in research have profound implications, limiting our understanding of how various conditions may differentially affect men and women, with downstream effects on treatment development and intervention. For example, longitudinal assessments show a differential cognitive trajectory between men and women contributing to sex differences in late-life dementia, with a higher prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias in women (Levine et al., Citation2021). Studies exploring gender-specific cognitive profiles may help elucidate the phenotypic heterogeneity seen in neurodegenerative conditions such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases, and aid in identifying social, health, and biological treatment targets (Duara & Barker, Citation2022; Fengler et al., Citation2016; Levine et al., Citation2021). This disparity becomes even more pronounced when considering certain minority samples of women, including women veterans, women athletes, elderly women, and women of color, who are consistently underrepresented in research studies (Bierer et al., Citation2022; D’Lauro et al., Citation2022; Vitale et al., Citation2017; Yano et al., Citation2010). Moreover, several topics specific to women’s health, such as cognitive changes related to times of hormonal change (e.g., pregnancy and menopause) remain vastly underexplored (Conde et al., Citation2021; Davies et al., Citation2018). By neglecting to include diverse populations and explore sex-specific factors, we are missing critical opportunities to enhance our knowledge and improve the quality of care provided to individuals from all backgrounds.

Although trends in representation of women in research have been delineated in other disciplines, this remains an understudied phenomenon in neuropsychology. Decades of research has established the impact of sex on certain domains of neuropsychological test performance (Heaton et al., Citation1986; Parsons & Prigatano, Citation1978; Yeudall et al., Citation1986), resulting in the development and use of demographically corrected norms that adjust for sex effects when appropriate. More recent research has explored the impact of sex-related conditions and disorders on neuropsychological functioning, including pregnancy and breast and gynecologic cancers (Correa et al., Citation2010; Henry & Randell, Citation2007; Morse et al., Citation2003). Despite the contributions of neuropsychology to the understanding of sex differences, there are still gaps in the literature, including a lack of data on whether and how sex is treated in neuropsychology research specifically. Understanding how women are represented in neuropsychological research may provide insight into the extent of sex bias and inform concrete recommendations as needed. As such, the goal of the present investigation was to evaluate representation of biological sex in neuropsychology publications.

All articles published in eight major peer-reviewed neuropsychology journals in the year 2019 were reviewed. The decision to restrict our review to 2019 was made for several reasons. First, intentional selection of one year was made in order to gain a recent snapshot of typical publication breakdown of sex in neuropsychology publications, in line with prior efforts in other disciplines (see Mamlouk et al., Citation2020). Second, we aimed to provide a snapshot of the research landscape just before the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, given the significant social and political changes that have occurred (and continue to occur) since that time. This review will provide a focused baseline examination of the state of representation of women in neuropsychology research within eight major peer-reviewed neuropsychology journals.

Specific aims were to: (1) describe representation of sex and/or women-specific topics, (2) quantify the overall proportion of women vs. men participants, (3) evaluate what percentage of studies included gender in analyses and discussion sections, and (4) assess whether studies included gender non-binary individuals or other gender minorities.

Methods

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

In order to be included in the current review, studies must have been published in the 2019 issues of one of the following journals: Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society (JINS; impact factor: 2.576), Neuropsychological Rehabilitation (impact factor: 2.556), Neuropsychology (impact factor: 2.333), The Clinical Neuropsychologist (TCN; impact factor: 2.232), Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology (JCEN; impact factor: 2.209), Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology (ACN; impact factor: 2.154), Journal of Neuropsychology (impact factor: 2.19), or Applied Neuropsychology: Adult (impact factor: 1.488). Journals were selected for their focus on neuropsychology (e.g., not primarily larger issues in cognitive neuroscience; not specific to pediatric neuropsychology), to limit the scope of the review. Within the general neuropsychology-focused journals, eight journals with the highest impact factor were selected. The publication period was restricted to research articles published in 2019 to provide a representative scope of neuropsychology literature prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Impact factors were derived from 2019 metrics. Exclusion criteria included: (a) non-human studies; (b) articles not available in English; and (c) review articles, editorials, meta-analyses, case studies, and conference abstracts.

Procedure

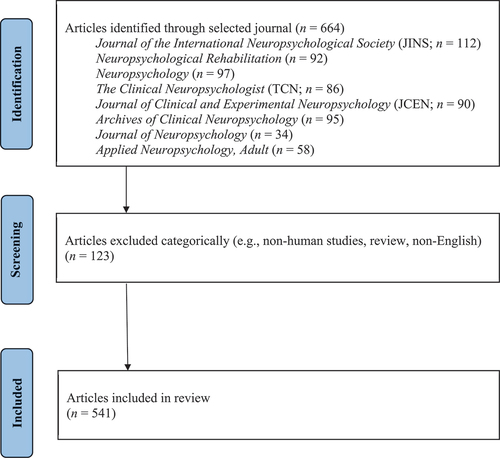

Articles were examined by a team of four independent researchers. Specifically, identified articles were screened in two stages by two independent researchers following methods employed in prior work (Mamlouk et al., Citation2020; Will et al., Citation2017). First, copies of all relevant articles (i.e., every 2019 article from the eight pertinent neuropsychology journals) were downloaded. In the first stage, titles and abstracts were screened for eligibility by two independent researchers. Specifically, two independent researchers screened out animal studies, review articles, editorials, meta-analysis, case studies, conference abstracts, and studies that were not available in English. Results were compared, and discrepancies were resolved through discussions during meetings. Please see for flowchart of inclusion and exclusion criteria.

After completing screening, included studies were assessed by two independent reviewers blinded to each other. Entries were analyzed for the following information: (a) was the main topic addressing a biological sex and/or gender issue?; (b) how was sex and/or gender categorized?; (c) what was the sex distribution of the sample?; (d) was biological sex considered in the analyses?; (e) was sex and/or gender addressed in the discussion?; and (f) what age categories did this study address?

For all articles reviewed, if biological sex was omitted, we indicated whether authors provided a rationale for the omission. Articles containing more than one sex and/or gender (e.g., men and women; male and females) were further evaluated for a description of the sample size by sex. Moreover, we examined whether sex was considered as an experimental variable. Articles were considered to have addressed sex in the analyses if the main independent variable was sex, sex was included as a covariate, or sex-stratified analyses were included. Study information was extracted into a standardized Excel spreadsheet. Inter-rater discrepancies in coding were resolved through discussions in which the original raters re-reviewed the assigned codes and their rationale. Coders reached agreement in all cases.

Statistical analyses

All data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Macintosh, version 28. Analyses were primarily descriptive in nature.

Results

Descriptive characteristics of articles

Out of the 541 articles meeting inclusion criteria, the majority of studies (n = 465) included samples of adult participants, 10 studies included adolescents, 29 included children, 10 included children, adolescents, and adults, 13 included adolescents and adults, and 14 included children and adolescents.

Description of sex/gender variables and methodology of data collection

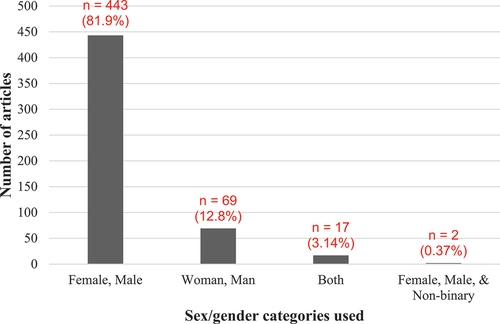

Use of “male/female” categories was most common (82%; see ), with only two studies (0.37%) including an option for non-binary gender identification. In 48 articles, sex identification was reported as being based on self-report; whereas, 13 studies indicated the use of medical records. Additionally, 3 studies employed a combination of self-report and medical records for sex identification. However, for over 85% of the articles (n = 467), the source of sex/gender classification was unreported.

Percentage of papers reporting sex/gender data

Ten articles (2%) omitted biological sex and gender data entirely. Across all studies that reported gender, participants were on average 48.2% female and 51.76% male. Forty-six out of the 541 eligible articles (8.5%) included 75% or more women in their sample; whereas, 90 studies (16.6%) reported 75% or more men in their samples. Of the 541 included studies, 88 (16.3%) matched by sex, while 227 (42%) disregarded sex in their analyses completely. Nearly 75% of the studies did not address sex or gender in the discussion (see ).

Table 1. Number and proportion of published articles by sex/gender focus.

Representation of women in articles

shows an overview of the number and proportion of articles by journal that mention sex/gender of participants and if the articles had a biological sex focus. Of the 541 articles included in this review, only 16 (3%) of the studies were sex-focused.

Of these, four studies examined sex differences in sports-related concussion or mild traumatic brain injury (TBI), one study investigated the impact of a self-help group among women with TBI, three studies examined sex differences in performance in either semantic categories (n = 1) or across adulthood (n = 2), and four studies examined normative data of cognitive tasks among women (n = 2) or among men and women (n = 2). The remaining studies examined sex differences in Parkinson’s disease (n = 1), sex differences in adaptive functioning following radiation treatment for pediatric posterior fossa tumors (n = 1), cognitive functioning and functional capacity in women with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD; n = 1), and verbal memory performance in women with remitted anorexia nervosa (n = 1). Eight studies included women-only samples, while sixteen studies included men-only samples. See for more information.

Table 2. Recommendations for clarity and transparency in sex and gender reporting.

Discussion

The present study investigated the representation of women in eight major peer-reviewed neuropsychology journals during the year 2019, with the aim of describing both quantitatively and qualitatively how researchers addressed sex and women’s issues prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Although similar reviews have been performed in other fields, most notably the related field of neuroscience (i.e., Mamlouk et al., Citation2020), this is the first study to systematically evaluate the inclusion of representation of women as participants in neuropsychology research.

Additionally, Medina et al. (Citation2021) previously outlined demographic variables in neuropsychological research, including sex, and highlighted a gradual increase in the reporting of sex/gender across neuropsychological studies over 15 years. Expanding upon this groundwork, our study advances prior research by conducting a more comprehensive analysis of women’s representation across various parameters. This includes examining how sex considerations are incorporated into analyses and discussions, the thematic relevance of papers to sex and/or gender issues, and the categorization of sex/gender within the literature.

Inclusion of sex- or women-focused topics

In total, only 3% of studies focused on gender, sex, or women’s issues, indicating a critical need for heightened efforts to enhance representation and, consequently, deepen our understanding of women’s issues in neuropsychology. Specifically, efforts should concentrate on two primary fronts: conducting robust, well-powered studies spanning both sexes and focusing solely on women. In studies encompassing both sexes, larger sample sizes are imperative to scrutinize the confluence of sex, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and other intersecting factors. Simultaneously, women are a heterogenous group and, as such, highly powered studies exclusively centered on their experiences can reveal further critical information germane to provision of neuropsychological healthcare services to this population. For instance, within-sex studies present an optimal framework to explore connections between brain health, cognitive function, and reproductive history indicators (e.g., reproductive span, number of children, use of menopause hormonal therapy, and hormonal contraceptives). Previous research suggests that reproductive history influences cognitive aging and risk for Alzheimer’s disease (e.g., Schelbaum et al., Citation2021), which may be important information to consider when interpreting neuropsychological data or tailoring recommendations to a client.

Our assertion is supported by an ever-growing message spanning several different research strands, including mild TBI (Merritt et al., Citation2019), Alzheimer’s disease (Nebel et al., Citation2018), epilepsy (Sullivan Baca et al., Citation2023), movement disorders (Meoni et al., Citation2020), and stroke (Cordonnier et al., Citation2017), all of which summarize the scant literature on sex differences and include calls to action to build on this literature base. The scarcity of such literature not only impedes our understanding of sex-specific differences in disorders affecting both men and women but also markedly hampers our knowledge of conditions predominantly impacting women.

For example, there were no papers in the literature we reviewed that focused on issues related to the influence of estrogen and other sex hormones on cognition either in the context of reproductive years, pregnancy, or menopause. This insufficient focus on women’s issues perpetuates a lack of understanding of how biological and psychosocial influences associated with times of hormonal change may affect neuropsychological presentation either independently (e.g., the influence of estrogen on domains of cognition or risk of neurodegeneration) or in conjunction with other conditions (e.g., TBI in combination with menopause). In a recent review paper focused on pregnancy-related stroke (Sullivan Baca et al., Citation2022), one of the present authors (E.S.) highlighted the fact that this condition has never been presented in a neuropsychology journal. This prompts contemplation on the number of analogous conditions observed clinically that are absent from the literature. This pursuit may encompass exploring the interaction between age, sex, and neuropsychological presentations across various conditions, delineating the differential effects of medications on cognition between men and women, and elucidating neurological complications secondary to intimate partner violence. Further, Clayton (Citation2016) suggested six neurological disorders that affect men and women differently and could be worthy candidates for future exploration. Overall, researchers must remain attentive to potential differences in neuropsychological presentations between men and women and actively explore and expand these fronts of inquiry.

Representation of women and men

The vast majority of reviewed studies included both women and men, with a relatively even distribution (48.24% and 51.76%, respectively). This is a more balanced distribution than published reviews of biological sex representation in other fields and provides an encouraging view of sex inclusion in neuropsychology. For example, in a review of the status of sex bias and omission in neuroscience, which included both human and animal model studies from 2017, only 52% of articles reported using both women and men (Mamlouk et al., Citation2020). As another example, a systematic review of clinical trials leading to FDA approval for cancer drugs from 2014 to 2019 demonstrated that while gender representation differed by tumor type, women were broadly underrepresented, with a distribution of 39.7% women and 60.3% men out of 60,000 participants (Dymanus et al., Citation2021).

Despite the relatively balanced sex distribution when averaging across all studies, there were twice as many studies that included only men compared to only women (16 vs. 8 studies), and nearly twice as many studies were comprised of a large majority of men (75% or more) compared to a large majority of women (16.6% vs. 8.5% of studies). The 24 studies assessing solely women or men examined a heterogeneous range of samples and topics (e.g., Veterans, HIV, head injury, opioid use disorder, weightlifters, normal development, breast cancer, anorexia, PTSD, Rett Syndrome, etc.). This may be partly accounted for by base rates for specific clinical conditions (e.g., almost exclusive occurrence of Rett Syndrome in women) or recruitment settings (e.g., Veteran Affairs system), where oversampling could be a more appropriate research method or there may be procedural limitations (Petriti et al., Citation2023). Nevertheless, while researchers examining certain populations such as Veterans and athletes may tend to exclude women due to an assumption of lower representation, this can inadvertently neglect the specific needs and interventions required for women within these groups. For example, a study investigating the enrollment and retention of men and women in VA Health Services Research and Development Trials found that the rate of women veterans who consented and completed research activities was at a similar or greater rate compared to men, despite a significantly higher base rate of male patients in the VA system (Goldstein et al., Citation2019). Therefore, although it may be appropriate for certain research questions to focus on a single sex, such studies should remain cautious of assumptions based on a condition or recruitment setting and instead strive to provide a compelling justification for such exclusion and discuss implications of excluding participants based on sex alone.

Consideration of sex and gender in analyses and discussion

Researchers have previously noted that enrolling women participants in clinical research studies does not necessarily translate to adequate analysis and reporting (Geller et al., Citation2018). While only 2% of the studies that we examined completely excluded biological sex, over half of studies did not consider sex in their analyses, even for the purposes of matching groups. Furthermore, 72% of articles did not mention sex considerations in their discussion or limitation sections, although this may not have been relevant for some studies (e.g., study focused on dystrophinopathy, which rarely affects women). Per our coding scheme, even if the lack of ability to perform sex-specific analyses was mentioned as a limitation, we coded an article as having addressed biological sex in the discussion. Thus, even using a liberal parameter for consideration of sex in the discussion, we found that most studies still did not address issues related to biological sex in discussion sections. This finding is consistent with previous research in broader psychological sciences, indicating that although studies may report sex breakdowns, few (17%) examine whether results are influenced by these contextual factors (Rad et al., Citation2018). We concur that conducting analytical examinations of human diversity, including sex, is essential for achieving a more nuanced understanding of outcomes.

Additional major issues included inconsistent use of the terms gender/sex, males/females, and women/men; limited information on how sex/gender is identified; and minimal inclusion of gender categories aside from a binary of men/women. Prior work has highlighted the distinctions between sex and gender and strategies for determining when and how to collect and report sex and gender data. Briefly, gender is a multidimensional term that refers to sociocultural norms, identities, and relations, and it can and does intersect with sex to affect health outcomes (Klinge, Citation2023). Best practice recommendations encourage stratifying results by sex, gender, or both, with careful exploration of the interactions between sex and gender and theory-driven rationale for investigating sex and gender differences (Hankivsky et al., Citation2018; Heidari et al., Citation2016; Springer et al., Citation2012).

A similar pattern of lack of consideration of sex as an experimental variable has been noted in neuroscience research (Beery & Zucker, Citation2011; Will et al., Citation2017) and randomized clinical trials (Geller et al., Citation2018). One study reported that only 12–25% of neuroscience articles published from 2010–2014 incorporated sex as an experimental variable (Will et al., Citation2017). A study of randomized control trials published in 2015 found that 26% reported at least one outcome by sex or explicitly included sex as a covariate, whereas the rest did not include sex as an outcome or explain reasons for this exclusion (Geller et al., Citation2018). When compared to these findings, our results suggest that neuropsychology research is considering sex as an experimental variable more often than is found in other fields.

It is important to note that all articles selected for the current study were from 2019, which is three years after the implementation of the National Institute of Health (NIH) Sex as a Biological Variable (SABV) regulatory policy (NIH, Citation2015). This policy does not require statistical tests examining sex as an experimental variable, but does require that, at a minimum, disaggregated data by sex is reported. This may in part explain the increased report of sex as an experimental variable compared to earlier studies in other fields (i.e., those examining articles published prior to the implementation of this NIH policy).

Given that sex has pervasive effects on biological functioning, consideration of sex in research is thought to be critical to the interpretation, validation, and generalizability of results (for review see Arnegard et al., Citation2020; Mauvais-Jarvis et al., Citation2020). NIH policies encourage that studies factor sex into all aspects of research, including study design, analyses, reporting, and interpretation. Disaggregation of data by sex will allow for comparisons of these groups and may ultimately inform interventions and facilitate precision medicine (Arnegard et al., Citation2020).

Inclusion of gender minorities

In addition to examining representation of women in neuropsychology research, we also sought to investigate inclusion of other gender minorities. Only two of the studies in our review provided a possible demographic option for gender minorities. One study offered distinct questions delineating sex at birth and gender, where a single participant identified within the “different identity” category (Lee & Suhr, Citation2019). In the second study, two participants identified with the “other” category for gender (Hirst et al., Citation2019). The available data do not provide clarity on whether additional studies did not provide these options or if these options were not chosen, potentially due to discomfort or reluctance to share this information. Nonetheless, these numbers considerably underrepresent the proportion of individuals within the general population identifying who identify as gender minorities.

Additionally, our review did not yield any studies explicitly focusing on gender minority issues within neuropsychology. There is a pronounced need for comprehensive research in this area to best inform our cognitive screening procedures, and to implement and develop interventions. Highlighting this urgency, a national longitudinal study, “Aging with Pride,” projected that the population of adults aged 50 and above identifying as sexual and gender minorities could surpass 5 million by 2060 (Fredriksen-Goldsen & Kim, Citation2017). Moreover, subjective cognitive difficulties are highly reported among this group, suggesting that this minority status may be a proxy risk factor for perceived cognitive decline (Brown & Patterson, Citation2020; Flatt et al., Citation2021). Another study found lower physical and psychological quality of life associated with sex and gender minority-related discrimination and victimization, identity stigma, insufficient food intake, and a higher rate of chronic medical conditions (Kim et al., Citation2022).

Recommendations to enhance representation of women in neuropsychology research

Clear and transparent reporting of sex and gender characteristics of participants is essential in advancing sex-equitable research practices. Throughout this review, several consistent limitations in this reporting have been identified (see for an overview of the current challenges and related recommendations). A common limitation was the lack of clarity in reporting the number of men/males and women/females in the studies. It is essential not only to transparently report sex and gender in sample demographics but also to maintain consistent reporting throughout the results. Explicitly stating in the results if specific analyses involve different numbers of men/males versus women/females from the overall sample size is imperative. Furthermore, when studies include only one sex or gender, clearly stating this in the manuscript title and abstract, alongside a methodological explanation in the background and methods sections, is recommended. Researchers are encouraged to utilize methodology-related best practices in recruitment of diverse samples (e.g., oversampling of marginalized groups), whenever feasible and/or appropriate.

Table 3. Number of published articles including samples of only women and/or men.

Correct usage of sex and gender terminology is crucial to avoid confusion. Distinguishing between “sex” and “gender” as distinct constructs with different meanings and employing specific gender terminology (e.g., “woman/girl,” “man/boy,” “non-binary person,” etc.) when referencing gender is important for accurate representation. The reported terminology should align with the terms used in data collection (e.g., do not report that your sample consisted of “cisgender males” unless you collected information on cis vs. trans gender identity from research participants) and the methodology used to collect that information (e.g., participant self-report, sex and/or gender listed in medical records, researcher observation, etc.). This includes indicating whether the data collection allowed for reporting non-binary gender identities or constrained participants to report a binary identity.

Future directions

Before addressing issues related to sex/gender reporting of study results, we must first consider future directions related to best practices on thorough sex/gender data collection. Researchers should be thoughtful to increase accuracy of the source of sex/gender demographics (e.g., prioritizing self-report vs. medical records and/or observation; ensuring there are options to allow for self-report of gender non-binary identities as discussed above). Several institutions have recommended separating sex, gender, and sexual orientation questions when possible and to offer an open-ended write-in option under “gender” (e.g., National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education; Committee on National Statistics; Committee on Measuring Sex, Gender Identity, and Sexual Orientation; Puckkett et al., Citation2020; Westbrook & Saperstein, Citation2015). Furthermore, journals and editorial staff can include specific guidelines and requirements for publication related to including data on sex and gender and addressing these topics in analyses and discussion sections. Journals can reference APA’s specific recommendations regarding best practices for reporting on gender (https://apastyle.apa.org/style-grammar-guidelines/bias-free-language/gender) as well as general principles for reducing bias (https://apastyle.apa.org/style-grammar-guidelines/bias-free-language/general-principles).

Furthermore, editorial staff can play a role by including experts in biological sex and gender minorities in the review process. In line with this recommendation, The Clinical Neuropsychologist created a Culture and Gender in Neuropsychology department intended to integrate culture and gender into the field and into editorial leadership in order to ensure better integration of these factors into manuscripts reviews (Hilsabeck & Marquine, Citation2022; Rivera Mindt & Hilsabeck, Citation2021), a structural change with the potential to be replicated across other journals. APA has helped foster the development of a number of recent Editorial Fellowship initiatives; programs specifically geared toward promoting and supporting participation by early career scientists from historically excluded groups to prepare them for editorial leadership). These types of programs may be another way to address gender/sex imbalances in neuropsychological science. Even within the programs, conscious efforts can be made to balance the composition of both the Fellows, as well as the Associate Editors and the Editorial Board in terms of sex/gender. Both researchers and journals may also consider consultation with professional organizations, such as APA and/or within neuropsychology the Queer Neuropsychological Society, on specific projects/publications as well as to improve larger programs and policies to future more inclusive gender/sex representation in both the research and editorial review process in the field.

In addition to editorial processes, we must also consider the characteristics and interests of the investigators who are conducting research in the field of neuropsychology. Babicz et al. (Citation2023) recently published on promising findings of no significant gender discrepancies in authorship or author byline position of manuscript submissions to four major clinical neuropsychology journals during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2019 and 2020. This is in contrast to other clinical fields, wherein underrepresentation of women in authorship remained prevalent, such as one study that cited discrepancies in first, last, and corresponding authors’ gender and the number of manuscripts that were submitted between 2018 and 2021 across 11 different biomedical journals (Gayet-Ageron et al., Citation2021). Taken together, while recent data suggests that women are equally represented among authors of neuropsychology articles, the support of initiatives to promote women researchers in the field remain imperative. In addition to the examples provided above, Babicz et al. suggest other ways to foster this positive change may include sponsorship and mentorship for women neuropsychologists through local, national, and international organizations (e.g., American Psychological Association’s Division 40: Women in Neuropsychology Committee and Division 35: Society for the Psychology of Women; National Academy of Neuropsychology’s Women in Leadership Committee), as well as the provision of information on available resources particularly for early career professionals whose research productivity may be at least partly impacted by limited time and/or support due to other responsibilities (e.g., childcare, household). We would be remiss to not acknowledge APA Division 40, Society for Clinical Neuropsychology (SCN)’s Women in Neuropsychology (WIN) recent (2022) special issue on mentoring in neuropsychology in collaboration with the Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology (JCEN), which had a specific focus on women and sexual/gender minorities from diverse background. Overall, although areas in need of improvement remain, it is important that we recognize these types of efforts as well as progress made in our field, and use the growing resources cited above to take deliberate steps that go beyond passive inclusion of sex and gender in the analysis, but rather put gender in the forefront of future neuropsychology research.

Limitations

It is important to acknowledge limitations to the current review. First, the review examined results from eight prominent neuropsychology journals in 2019, providing a snapshot in time of the representation of women in neuropsychology. This approach may not fully represent an exhaustive analysis of all neuropsychological journals. Moreover, although we believe this was an effective approach to describe representation of women and biological sex in our field, its applicability to related fields within psychology may be limited.

Another limitation pertains to the scope of the study. Though we included studies examining pediatric and adolescent samples, our primary focus was on adults, and we did not specifically investigate pediatric neuropsychology research. Nevertheless, it’s crucial to recognize that gender/sex bias might manifest differently in child and adolescent populations within the field of neuropsychology. Future research should thoroughly examine the representation of girls in pediatric neuropsychological studies. Moreover, to be included in the current review, articles had to be published in English, which limited the generalizability of our study. Since considering linguistic and sociocultural dimensions may offer insights into the representation of gender constructs and the linguistic representation of sex/gender labels, future research would benefit from a more expansive approach. Similarly, while we did examine the representation of women in neuropsychological research, our analysis did not specifically capture intersectional categories within sex, such as older women and women of color. Exploring intersectionality has the potential to reveal nuanced sex representation patterns and disparities in research foci, thus enhancing our comprehension of sex/gender bias within neuropsychology.

In addition to scope-related limitations, this review did not explicitly investigate the base rates of specific conditions and/or recruitment settings as part of the statistical analysis. Further investigation into base rates may assist with delineating issues pertaining to institutional or procedural barriers versus gender and other culturally-based biases, which can inform our field on ways to develop more targeted solutions. Future research may take one step further and include a breakdown of base rates for conditions of interest and/or recruitment settings as part of the statistical analyses, particularly of conditions that are known to predominantly affect women. Examples of clinical conditions that are understudied in women (despite either relatively affecting men and women at similar rates or with high prevalence in women) and warrant more attention in future research may include lung cancer, cardiovascular disease, and chronic conditions in women as proposed by the National Institutes of Health’s Advisory Committee on Research on Women’s Health (Duma et al., Citation2018; Reza et al., Citation2022; Temkin et al., Citation2023; Tobb et al., Citation2022).

Additionally, the review did not assess whether the studies included in the analysis were sufficiently powered to detect sex and gender differences. Furthermore, while we did take note of studies that were focused on biological sex-specific topics, we acknowledge that a comprehensive examination of these subjects, such as menopause and pregnancy-related stroke, would warrant separate and in-depth review papers dedicated to each of these areas. Additionally, we did not contact authors to determine reasons for certain trends (i.e., omission of women, overrepresentation of men, lack of inclusion of gender minorities, reason for sex/gender terminology, etc.). Given the broad variability of reviewed articles in their usage of the terms “sex/gender” “men/women” and “males/females,” we attempted to standardize our wording to refer to gender and men/women. However, in doing so, some specific issues related to sex versus gender may have been undermined.

We selected the year for analysis considering the potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on publishing trends. Although early data suggests that women were not underrepresented in authorship of neuropsychology manuscripts during the pandemic (Babicz et al., Citation2023), the full extent of anomalous trends remains unclear. As such, we chose a year just preceding the pandemic to be proximal to the current time while minimizing the unknown effects of such publishing trends on biological sex representation in the literature. While we do not consider the year chosen to be a limitation per se, we do want to acknowledge more contemporary women and biological sex-focused efforts, including those addressing professional issues in neuropsychology (e.g., Klipfel et al., Citation2023; Matchanova et al., Citation2022; Rohling et al., Citation2022), those addressing sex differences in specific conditions such as HIV (Dreyer et al., Citation2022) and TBI due to intimate partner violence (Raskin et al., Citation2023), and those investigating intersectional variables, such as the interplay between race, age, and sex (Dixon et al., Citation2021; Hill-Jarrett & Jones, Citation2022).

Conclusions

Overall, the present study highlights the significant limitations in the field of neuropsychology in our understanding of how biological and psychosocial influences of sex and related hormonal presentations may affect neuropsychological presentation, both for women and gender minorities. Although much of current research, as assessed by a review of research published from eight prominent neuropsychology journals in 2019, included both men and women in their data collection, gender minorities are not included in a representative way as indicated by their proportion in the U.S. population, and neither women nor gender minorities were systemically included in analyses and results across studies. Notably, our field and current understanding of the cognitive sequela of medical and psychiatric conditions will stagnate without an understanding of how biological and sociocultural differences in the population may mediate or moderate cognitive outcomes. This may in turn create a cyclical effect, in which these incomplete findings across our field are then disseminated to researchers and students/trainees, which may risk subsequently moving through their training and profession to perpetuate these knowledge gaps in their own research and clinical practice, ultimately disserving both the field of neuropsychology and patients.

We hope the present study is a call to action for the field of neuropsychology, such that even during graduate training, students/trainees begin to appreciate the current limitation of our knowledge for various populations (e.g., women and gender minorities) and actively consider how to mitigate these limitations with best practices in research design, representative sample collection, and data analysis and reporting for generation of more sex/gender-inclusive and representative research findings. Further, we encourage other institutional/organizational drivers of research, such as grant funders and publishers, to continue to push for public and clear expectations regarding inclusion of sex analyses in research, as well as for diverse reviewers/editors to help support these systemic changes in processes. It is our hope that should a replication of the current study be carried out in a few years’ time, that we will see dramatically different results, thereby moving our field forward in our understanding how sex as a biological variable and related hormonal differences may differentially impact cognitive risk and resilience factors for various clinical presentations and outcomes for both women and gender minorities.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The term “females” is most appropriately used to describe biological sex; whereas, “women” is used to describe gender. However, for brevity, the terms “females” and “women” will be grouped under the term “women” where possible.

2. While acknowledging that sex and gender are separate constructs, the terms “sex” and “gender” will be grouped together under the term “sex” for the sake of brevity where possible. Of note, sex is intentionally used over gender in this context, given its reference to a biological versus social construct.

References

- Arnegard, M. E., Whitten, L. A., Hunter, C., & Clayton, J. A. (2020, June). Sex as a biological variable: A 5-year progress report and call to action. Journal of Women’s Health (Larchmt), 29(6), 858–864. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2019.8247. Epub 2020 Jan 22. PMID: 31971851; PMCID: PMC7476377.

- Babicz, M. A., Matchanova, A., Broomfield, R., DesRuisseaux, L. A., Gereau, M. M., Brothers, S. L., Radigan, L., Porter, E., Lee, G. P., Rapport, L. J., Suchy, Y., Yeates, K. O., & Woods, S. P. (2023). Was the COVID-19 pandemic associated with gender disparities in authorship of manuscripts submitted to clinical neuropsychology journals? Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355617721001375

- Beery, A. K., & Zucker, I. (2011). Sex bias in neuroscience and biomedical research. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 35(3), 565–572. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.07.002

- Bierer, B. E., Meloney, L. G., Ahmed, H. R., & White, S. A. (2022). Advancing the inclusion of underrepresented women in clinical research. Cell Reports Medicine, 3(4), 100553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrm.2022.100553

- Brown, M. J., & Patterson, R. (2020). Subjective cognitive decline among sexual and gender minorities: Results from a U.S. population-based sample. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 73(2), 477–487. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-190869

- Clayton, J. A. (2016). Sex influences in neurological disorders: Case studies and perspectives. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 18(4), 357–360. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2016.18.4/jclayton

- Conde, D. M., Verdade, R. C., Valadares, A. L. R., Mella, L. F. B., Pedro, A. O., & Costa-Paiva, L. (2021). Menopause and cognitive impairment: A narrative review of current knowledge. World Journal of Psychiatry, 11(8), 412–428. https://doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v11.i8.412

- Cordonnier, C., Sprigg, N., Sandset, E. C., Pavlovic, A., Sunnerhagen, K. S., Caso, V., & Christensen, H. (2017). Stroke in women—from evidence to inequalities. Nature Reviews Neurology, 13(9), 521–532. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2017.95

- Correa, D. D., Zhou, Q., Thaler, H. T., Maziarz, M., Hurley, K., & Hensley, M. L. (2010). Cognitive functions in long-term survivors of ovarian cancer. Gynecologic Oncology, 119(2), 366–369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.06.023

- Davies, S. J., Lum, J. A., Skouteris, H., Byrne, L. K., & Hayden, M. J. (2018). Cognitive impairment during pregnancy: A meta‐analysis. The Medical Journal of Australia, 208(1), 35–40. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja17.00131

- Dixon, J. S., Coyne, A. E., Duff, K., & Ready, R. E. (2021). Predictors of cognitive decline in a multi-racial sample of midlife women: A longitudinal study. Neuropsychology, 35(5), 514–528. https://doi.org/10.1037/neu0000743

- D’Lauro, C., Jones, E. R., Swope, L. M., Anderson, M. N., Broglio, S., & Schmidt, J. D. (2022). Under-representation of female athletes in research informing influential concussion consensus and position statements: An evidence review and synthesis. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 56(17), 981. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2021-105045

- Dreyer, A. J., Munsami, A., Williams, T., Andersen, L. S., Nightingale, S., Gouse, H., Joska, J., & Thomas, K. G. F. (2022). Cognitive differences between men and women with HIV: A systematic review and meta analysis. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 37(2), 479–496. https://doi.org/10.1093/arclin/acab068

- Duara, R., & Barker, W. (2022). Heterogeneity in Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis and progression rates: Implications for therapeutic trials. Neurotherapeutics, 19(1), 8–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13311-022-01185-z

- Duma, N., Vera Aguilera, J., Paludo, J., Haddox, C. L., Gonzalez Velez, M., Wang, Y., Leventakos, K., Hubbard, J. M., Mansfield, A. S., Go, R. S., & Adjei, A. A. (2018). Representation of minorities and women in oncology clinical trials: Review of the past 14 years. Journal of Oncology Practice, 14(1), e1–e10. https://doi.org/10.1200/JOP.2017.025288

- Dymanus, K. A., Butaney, M., Magee, D. E., Hird, A. E., Luckenbaugh, A. N., Ma, M. W., Hall, M. E., Huelster, H. L., Laviana, A. A., Davis, N. B., Terris, M. K., Klaassen, Z., & Wallis, C. J. D. (2021). Assessment of gender representation in clinical trials leading to FDA approval for oncology therapeutics between 2014 and 2019: A systematic review‐based cohort study. Cancer, 127(17), 3156–3162. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.33533

- Feldman, J. R. (2019). Gender on the divide: The dandy in modernist literature. Cornell University Press. https://doi.org/10.7591/9781501734519

- Fengler, S., Roeske, S., Heber, I., Reetz, K., Schulz, J. B., Riedel, O., Wittchen, H. U., Storch, A., Linse, K., Baudrexel, S., Hilker, R., Mollenhauer, B., Witt, K., Schmidt, N., Balzer-Geldsetzer, M., Dams, J., Dodel, R., Gräber, S., Pilotto, A., & Kassubek, J.… Kalbe, E. (2016). Verbal memory declines more in female patients with Parkinson’s disease: The importance of gender-corrected normative data. Psychological Medicine, 46(11), 2275–2286. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291716000908

- Flatt, J. D., Cicero, E. C., Lambrou, N. H., Wharton, W., Anderson, J. G., Bouldin, E. D., McGuire, L. C., & Taylor, C. A. (2021). Subjective cognitive decline higher among sexual and gender minorities in the United States, 2015-2018. Alzheimer’s & Dementia (New York, NY), 7(1), e12197. https://doi.org/10.1002/trc2.12197

- Fredriksen-Goldsen, K. I., & Kim, H.-J. (2017). The science of conducting research with LGBT older adults- an introduction to aging with pride: National Health, aging, and Sexuality/Gender study (NHAS). The Gerontologist, 57(suppl 1), S1–S14. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnw212

- Gayet-Ageron, A., Ben Messaoud, K., Richards, M., & Schroter, S. (2021). Female authorship of COVID-19 research in manuscripts submitted to 11 biomedical journals: Cross sectional study. BMJ, 375, n2288. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n2288

- Geller, S. E., Koch, A. R., Roesch, P., Filut, A., Hallgren, E., & Carnes, M. (2018). The more things change, the more they stay the same: A study to evaluate compliance with inclusion and assessment of women and minorities in randomized controlled trials. Academic Medicine, 93(4), 630–635. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002027

- Goldstein, K. M., Duan-Porter, W., Alkon, A., Olsen, M. K., Voils, C. I., & Hastings, S. N. (2019). Enrollment and retention of men and women in health services research and development trials. Women’s Health Issues, 29 Suppl 1(Suppl 1), S121–S130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2019.03.004

- Hankivsky, O., Springer, H. W., & Hunting, G. (2018). Beyond sex and gender difference in funding and reporting of health research. Research Integrity and Peer Review, 3(6). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41073-018-0050-6

- Heaton, R. K., Grant, I., & Matthews, C. G. (1986). Differences in neuropsychological test performance associated with age, education, and sex. In I. Grant & K. M. Adams (Eds.), Neuropsychological assessment of neuropsychiatric disorders (pp. 100–120). Oxford University Press.

- Heidari, S., Babor, T. F., de Castro, P., Tort, S., & Curno, M. (2016). Sex and gender equity in research: Rationale for the SAGER guidelines and recommended use. Research Integrity and Peer Review, 1(2). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41073-016-0007-6

- Henry, J. D., & Randell, P. G. (2007). A review of the impact of pregnancy on memory function. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 29(8), 793–803. https://doi.org/10.1080/13803390701612209

- Hill-Jarrett, T. G., & Jones, M. K. (2022). Gendered racism and subjective cognitive complaints among older black women: The role of depression and coping. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 36(2), Article 2. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2021.1923804

- Hilsabeck, R. C., & Marquine, M. J. (2022). Editorial from the TCN department of culture and gender in neuropsychology: Moving the field toward broader representation in neuropsychological studies. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 36(4), 779–789. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2022.2056924

- Hirst, R. B., Watson, J., Rosen, A. S., & Quittner, Z. (2019). Perceptions of the cognitive effects of cannabis use: A survey of neuropsychologists’ beliefs. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 41(2), 133–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/13803395.2018.1503644

- Kim, H. J., Fredriksen‐Goldsen, K., & Jung, H. H. (2022). Health‐related quality of life among sexual and gender minority older adults living with cognitive impairment. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 18(S8), e063193. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.063193

- Klinge, I. (2023). Best practices in the study of gender. In C. Gibson & L. A. M. Galea (Eds.), Sex differences in brain function and dysfunction (pp. 27–46). Springer Nature Switzerland. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-26723-9.

- Klipfel, K. M., Sweet, J. J., Nelson, N. W., & Moberg, P. J. (2023). Gender and ethnic/racial diversity in clinical neuropsychology: Updates from the AACN, NAN, SCN 2020 practice and salary survey. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 37(2), 231–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2022.2054360

- Lee, G. J., & Suhr, J. A. (2019). Expectancy effects on self-reported attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity disorder symptoms in simulated neurofeedback: A pilot study. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 34(2), 200–205. https://doi.org/10.1093/arclin/acy026

- Levine, D. A., Gross, A. L., Briceño, E. M., Tilton, N., Giordani, B. J., Sussman, J. B., Hayward, R. A., Burke, J. F., Hingtgen, S., Elkind, M. S. V., Manly, J. J., Gottesman, R. F., Gaskin, D. J., Sidney, S., Sacco, R. L., Tom, S. E., Wright, C. B., Yaffe, K., & Galecki, A. T. (2021). Sex differences in cognitive decline among US adults. JAMA Network Open, 4(2), e210169–e210169. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0169

- Mamlouk, G. M., Dorris, D. M., Barrett, L. R., & Meitzen, J. (2020). Sex bias and omission in neuroscience research is influenced by research model and journal, but not reported NIH funding. Frontiers in neuroendocrinology, 57, 100835. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yfrne.2020.100835

- Matchanova, A., Avci, G., Babicz, M. A., Thompson, J. L., Johnson, B., Ke, I. J., Rahman, S., Sullivan, K. L., Sheppard, D. P., Morales, Y., Tierney, S. M., Kordovski, V. M., Beltran-Najera, I., Ulrich, N., Pilloff, S., Yeates, K. O., & Woods, S. P. (2022). Gender disparities in the author bylines of articles published in clinical neuropsychology journals from 1985 to 2019. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 36(6), 1226–1243. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2020.1843713

- Mauvais-Jarvis, F., Bairey Merz, N., Barnes, P. J., Brinton, R. D., Carrero, J. J., DeMeo, D. L., de Vries, G. J., Epperson, C. N., Govindan, R., Klein, S. L., Lonardo, A., Maki, P. M., McCullough, L. D., Regitz-Zagrosek, V., Regensteiner, J. G., Rubin, J. B., Sandberg, K., & Suzuki, A. (2020, August 22). Sex and gender: Modifiers of health, disease, and medicine. Lancet, 396(10250), 565–582. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31561-0. Erratum in: Lancet. 2020 Sep 5;396(10252):668. PMID: 32828189; PMCID: PMC7440877.

- Medina, L. D., Torres, S., Gioia, A., Lopez, A. O., Wang, J., & Cirino, P. T. (2021). Reporting of demographic variables in neuropsychological research: An update of O’Bryant.’s trends in the current literature. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 27(5), 497–507. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355617720001083

- Meoni, S., Macerollo, A., & Moro, E. (2020). Sex differences in movement disorders. Nature Reviews Neurology, 16(2), 84–96. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-019-0294-x

- Merritt, V. C., Padgett, C. R., & Jak, A. J. (2019). A systematic review of sex differences in concussion outcome: What do we know? The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 33(6), 1016–1043. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2018.1508616

- Morse, R., Rodgers, J., Verill, M., & Kendell, K. (2003). Neuropsychological functioning following systemic treatment in women treated for breast cancer: A review. European Journal of Cancer, 39(16), 2288–2297. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-8049(03)00600-2

- National Institutes of Health. (2015). Consideration of Sex As a Biological Variable in NIH-Funded Research. https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/not-od-15-102.html

- Nebel, R. A., Aggarwal, N. T., Barnes, L. L., Gallagher, A., Goldstein, J. M., Kantarci, K., Mallampalli, M. P., Mormino, E. C., Scott, L., Yu, W. H., Maki, P. M., & Mielke, M. M. (2018). Understanding the impact of sex and gender in Alzheimer’s disease: A call to action. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 14(9), 1171–1183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2018.04.008

- Parsons, O. A., & Prigatano, G. P. (1978). Methodological considerations in clinical neuropsychological research. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 46(4), 608–619. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.46.4.608

- Petriti, U., Dudman, D. C., Scosyrev, E., & Lopez-Leon, S. (2023). Global prevalence of Rett syndrome: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Systematic Reviews, 12(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-023-02169-6

- Puckkett, J. A., Brown, N. C., Dunn, T., Mustanski, B., & Newcomb, M. E. (2020). Perspectives from transgender and gender diverse people on how to ask about gender. LGBT Health, 7(6), 305–311. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2019.0295

- Rad, M. S., Martingano, A. J., & Ginges, J. (2018). Toward a psychology of Homo sapiens: Making psychological science more representative of the human population. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(45), 11401–11405. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1721165115

- Raskin, S. A., DeJoie, O., Edwards, C., Ouchida, C., Moran, J., White, O., Mordasiewicz, M., Anika, D., & Njoku, B. (2023). Traumatic brain injury screening and neuropsychological functioning in women who experience intimate partner violence. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 38(2), 354–376. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2023.2215489

- Reza, N., Gruen, J., & Bozkurt, B. (2022). Representation of women in heart failure clinical trials: Barriers to enrollment and strategies to close the gap. American Heart Journal Plus: Cardiology Research and Practice, 13, 100093. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahjo.2022.100093

- Rivera Mindt, M., & Hilsabeck, R. C. (2021). Introductory editorial to the special issue on white privilege in neuropsychology and norms for Spanish-speakers of the US-Mexico border region. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 35(2), 201–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2020.1866076

- Rohling, M. L., Ready, R. E., Dhanani, L. Y., & Suhr, J. A. (2022). Shift happens: The gender composition in clinical neuropsychology over five decades. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 36(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2020.1778791

- Schelbaum, E., Loughlin, L., Jett, S., Zhang, C., Jang, G., Malviya, N., Hristov, H., Pahlajani, S., Isaacson, R., Dyke, J. P., Kamel, H., Brinton, R. D., & Mosconi, L. (2021 December 7). Association of reproductive history with brain MRI biomarkers of dementia risk in midlife. Neurology, 97(23), e2328–e2339. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000012941. Epub 2021 Nov 3. PMID: 34732544; PMCID: PMC8665431.

- Shansky, R. M., & Woolley, C. S. (2016). Considering sex as a biological variable will be valuable for neuroscience research. Journal of Neuroscience, 36(47), 11817–11822. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1390-16.2016

- Springer, K. W., Stellman, J. M., & Jordan-Young, R. M. (2012). Beyond a catalogue of differences: A theoretical frame and good practice guidelines for researching sex/gender in human health. Social Science & Medicine, 74(11), 1817–1824. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.05.033

- Sullivan Baca, E., Lorkiewicz, S. A., Rehman, R., van Cott, A. C., Towne, A. R., & Haneef, Z. (2023). Utilization of epilepsy care among women veterans: A population-based study. Epilepsy Research, 192, 107130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2023.107130

- Sullivan Baca, E., Modiano, Y. A., McKenney, K. M., & Carlew, A. R. (2022). Pregnancy-related stroke through a neuropsychology lens. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2022.2131631

- Temkin, S. M., Barr, E., Moore, H., Caviston, J. P., Regensteiner, J. G., & Clayton, J. A. (2023). Chronic conditions in women: The development of a National Institutes of Health framework. BMC Women’s Health, 23(1), 162. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-023-02319-x

- Tobb, K., Kocher, M., & Bullock-Palmer, R. P. (2022). Underrepresentation of women in cardiovascular trials-it is time to shatter this glass ceiling. American Heart Journal Plus: Cardiology Research and Practice, 13, 100109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahjo.2022.100109

- Vitale, C., Fini, M., Spoletini, I., Lainscak, M., Seferovic, P., & Rosano, G. M. (2017). Under-representation of elderly and women in clinical trials. International Journal of Cardiology, 232, 216–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.01.018

- Westbrook, L., & Saperstein, A. (2015). New categories are not enough: Rethinking the measurement of sex and gender in social surveys. Gender & Society, 29(4), 534–560. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243215584758

- Will, T. R., Proaño, S. B., Thomas, A. M., Kunz, L. M., Thompson, K. C., Ginnari, L. A., Jones, C. H., Lucas, S.-C., Reavis, E. M., Dorris, D. M., & Meitzen, J. (2017). Problems and progress regarding sex bias and omission in neuroscience research. Eneuro, 4(6), ENEURO.0278–17.2017. https://doi.org/10.1523/ENEURO.0278-17.2017

- Yano, E. M., Hayes, P., Wright, S., Schnurr, P. P., Lipson, L., Bean-Mayberry, B., & Washington, D. L. (2010). Integration of women veterans into VA quality improvement research efforts: What researchers need to know. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 25(S1), 56–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-009-1116-4

- Yeudall, L. T., Fromm, D., Reddon, J. R., & Stefanyk, W. O. (1986). Normative data stratified by age and sex for 12 neuropsychological tests. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 42(6), 918–946. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-4679(198611)42:6<918:AID-JCLP2270420617>3.0.CO;2-Y