Abstract

Objective

The decline in suicide rates has leveled off in many countries during the last decade, suggesting that new interventions are needed in the work with suicide prevention. Learnings from investigations of suicide should contribute to the development of these new interventions. However, reviews of investigations have indicated that few new lessons have been learned. To be an effective tool, revisions of the current investigation methods are required. This review aimed to describe the problems with the current approaches to investigations of suicide as patient harm and to propose ways to move forward.

Methods

Narrative literature review.

Results

Several weaknesses in the current approaches to investigations were identified. These include failures in embracing patient and system perspectives, not addressing relevant factors, and insufficient competence of the investigation teams. Investigation methods need to encompass the progress of knowledge about suicidal behavior, suicide prevention, and patient safety.

Conclusions

There is a need for a paradigm shift in the approaches to investigations of suicide as potential patient harm to enable learning and insights valuable for healthcare improvement. Actions to support this paradigm shift include involvement of patients and families, education for investigators, multidisciplinary analysis teams with competence in and access to relevant parts across organizations, and triage of cases for extensive analyses. A new model for the investigation of suicide that support these actions should facilitate this paradigm shift.

There are weaknesses in the current approaches to investigations of suicide.

A paradigm shift in investigations is needed to contribute to a better understanding of suicide.

New knowledge of suicidal behavior, prevention, and patient safety must be applied.

HIGHLIGHTS

INTRODUCTION

Although the global suicide rate has decreased over the last three decades, suicide remains a major public health problem with approximately 700,000 deaths every year (World Health Organization, Citation2021). The decrease has leveled off during the last decade, suggesting that new suicide-reducing interventions are needed.

Suicidal behaviors are heterogeneous and complex and are influenced by biological, psychological, and social factors interacting over time (Hawton & van Heeringen, Citation2009; Mann & Currier, Citation2010; Nock et al., Citation2008; Turecki et al., Citation2019; van Heeringen & Mann, Citation2014). Hence, a variety of interventions are needed to reduce suicidal behavior and save lives (Hawton & Pirkis, Citation2017; Hofstra et al., Citation2020; Ishimo et al., Citation2021). Learning from investigations of suicide cases will contribute to the development of such interventions.

However, our recently published review of investigations of healthcare regarding suicides in Sweden showed that the investigations were framed to respond to the template of the supervisory authority rather than analyzing the complexity of suicide and safety (Fröding et al., Citation2021). Further, recurrent deficiencies and failures in healthcare were identified in the investigations over the years, suggesting that the current investigation strategies are not sufficient to reduce current levels of suicide.

If investigations of suicide cases are to be an effective tool for advances in learning and suicide prevention, adaptations of investigation methods, approaches and performance to current knowledge and the context of healthcare at present are required. Knowledge and perspectives from both the science of patient safety and suicidology and patients are necessary to achieve this ambition.

Understanding Suicidal Behavior: implications for Investigations

Risk factors for suicidal behavior are known, such as male sex, psychiatric disorders, prior suicide attempts, alcohol and substance abuse, heredity, negative life events, and trauma (Hawton & van Heeringen, Citation2009; Turecki & Brent, Citation2016). Studies show that a large proportion of the individuals who took their lives were in contact with healthcare close to the time of death (Ahmedani et al., Citation2019; Bergqvist et al., Citation2022; Chock et al., Citation2019; Stene-Larsen & Reneflot, Citation2019). The experiences of suicidal patients and learning from prior suicide attempts could contribute to important perspectives on safety in healthcare (Berg, Rortveit, & Aase, Citation2017; Berg et al., Citation2020).

There is a growing body of evidence for suicide prevention strategies in healthcare, including the identification and proper treatment of psychiatric disorders and abuse, psychotherapy, brief interventions, and safety planning (Doupnik et al., Citation2020; Mann, Michel, & Auerbach, Citation2021). However, there is no algorithm to predict suicide in clinical practice, and the management of further advances in suicide prevention requires more understanding of how to translate this knowledge into effective action (Ngwena, Hosany, & Sibindi, Citation2017).

Psychological theories can provide a framework to understand how a complex interplay of factors combines to increase the risk of suicide, and to identify potentially modifiable targets for treatment and reducing suicide risk (Klonsky & May, Citation2015; O’Connor, Citation2011; Rudd, Citation2006). The intensity of suicidality and the capability to act are influenced by different psychological factors in personality and cognition, social circumstances, and life events (O'Connor & Nock, Citation2014). Several of these factors change over time, and fluctuate in ways that are not always predictable. Some of these factors are modifiable, at least to some extent, raising the possibility of preventative interventions (Klonsky et al., Citation2021; O'Connor & Kirtley, 2018).

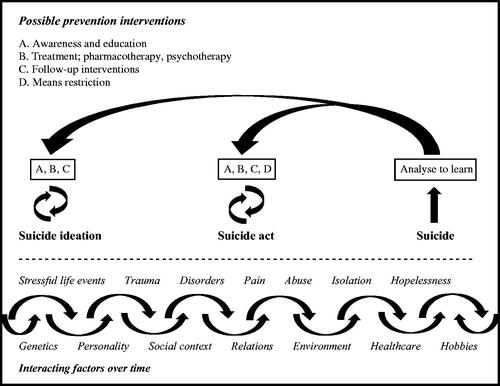

Incorporating the current knowledge of suicidal behavior and suicide prevention into the investigation of suicides could enable effective improvement in suicide prevention ().

FIGURE 1. Illustration of the suicide process from ideation to act and examples of possible suicide prevention interventions, after Targets and methods of suicide prevention, Mann, J. et al. (Citation2021).

Current Approaches to Suicide Investigation

Deaths occurring in healthcare services can be an affront to the expectations of a high level of safety in healthcare. However, healthcare has always been, and continues to be, a risk-laden sector with highly complex therapies, diagnostics, and interventions. Globally, millions of patients annually suffer patient harm, injuries, or death because of poor quality or unsafe healthcare that could have been avoided if appropriate action had been taken by healthcare professionals (World Health Organization, Citation2022). Systematic reporting and investigation of patient harm to identify risks and improve patient safety have become widespread safety improvement strategies (Anderson et al., Citation2013; Leape, Citation2002; National Institute for Health and Welfare, Citation2009). These strategies have expanded our understanding of vulnerabilities in healthcare systems and the prevention of harm from healthcare (Bates & Singh, Citation2018). However, excessive reliance on incident investigation alone has been questioned and is under reassessment (Macrae, Citation2016; Mitchell et al., Citation2016; Peerally et al., Citation2017; Shojania & Thomas, Citation2013; Trbovich & Shojania, Citation2017). The paradigm predominant across incident analysis in healthcare is a linear, cause-and-effect approach with a focus on deviations and non-adherence, which has been labeled Safety-I (Hollnagel, Wears, & Braithwaite, Citation2015). This approach can lead to significant learning within the system. However, these learnings are most effective when activities are well-understood, relatively stable, and have limited external influences (Braithwaite et al., Citation2015), which is not the signature of the usual complex settings around a suicidal person who often suffers from mental illness and social problems (Fortin et al., Citation2021; Turecki et al., Citation2019).

Despite the development of different methods for investigating incidents in healthcare (Hagley et al., Citation2019), root cause analysis (RCA) remains the predominant approach for investigating suicide (Gillies, Chicop, & O’Halloran, Citation2015). The method has been criticized for failing to adequately consider the central aspects of the phenomenon, such as patient factors, because the focus is at a systemic level (Vrklevski, McKechnie, & OʼConnor, Citation2018). The expectation of finding a single or limited number of “root causes” seems to be a gross oversimplification (Neal et al., Citation2004; Vincent, Citation2003). Psychological autopsy is used to examine the psychological and contextual circumstances preceding suicide (Hawton et al., Citation1998; Isometsä, Citation2001). However, literature on other methods for investigating suicide is sparse.

Suicide as an incident of possible patient harm (i.e., preventable with appropriate actions by healthcare) differs from other adverse events in healthcare, which, in some ways, presents additional challenges. Most suicides occur outside hospitals in the homes of patients, with no staff or witnesses (Rajendran et al., Citation2022). Further, the care of patients with suicidal behavior is often carried out over a long time by different providers, and work with patient safety is traditionally centered on hospitals and investigations of patient harm performed within a single unit (Roos af Hjelmsäter et al., Citation2019).

This review aimed to describe the problems with the current approaches of investigations of adverse events in healthcare applicable to investigations of suicides as incidents of patient harm and to propose and discuss ways to move forward.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This review was performed interactively by the authors, researchers, and working professionals in psychiatry and suicidology (EF and ÅW), patient safety (AR, CV, and EF), and improvement in healthcare (BAG).

This review followed the methodological framework of scoping reviews described by Arksey and O’Malley (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005). The scope of this study was investigations of suicide as incidents of patient harm in healthcare, and the research question was two-fold: What problems with the current approaches to investigations of patient harm applicable to investigations of suicides as incidents of patient harm are described in the literature, and what are the evidence to support changes to address the problems?

The searches were performed by EF, and the search strategy was developed in consultation with a professional university librarian with the express purpose to identify relevant literature for the study question. Searches were performed in 2021 in PubMed, PsycINFO, and Cochrane databases. In PubMed and PsycINFO, the terms used were suicide combined with each of the following: patient safety, analysis, investigation, investigation methodology, patient harm, incident, root cause analysis, psychological autopsy, failure mode and effect analysis, and fault tree analysis. Searches were also performed using patient safety in combination with analysis and investigation. Furthermore, patient harm and investigation were combined. The searches were restricted to the English language and search terms in the title/abstract. In Cochrane, reviews were searched using topics (health & safety at work and methodology) and keywords in the title (patient safety, suicide prevention, incident analysis, and investigation). This study did not include systematic searches of gray literature.

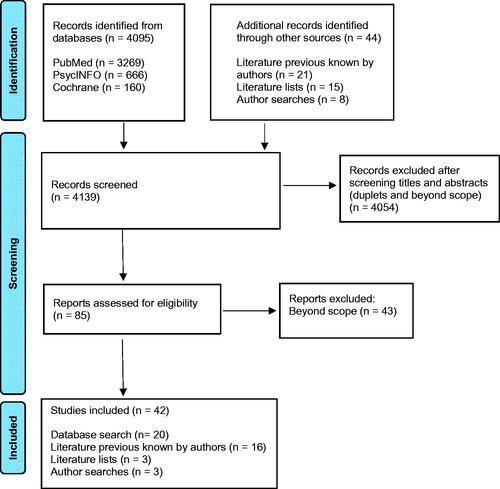

The titles and abstracts were reviewed and screened for relevance to the study. Inclusion criteria were studies on investigations of suicide, investigative methods, and methodologies for analyses of incidents of patient harm. Studies not applicable to the investigation of suicide were excluded. Examples include studies focusing on specific processes or incidents in areas that were not perceived as applicable to suicide, such as radiology and pathology, and studies focusing on the investigation of other specific forms of harm. The selected studies were read in full text, and eligible studies for the study aim were included. Reference lists of included studies were screened for relevant records, and searches for further literature by authors of the included studies were performed using Google Scholar. Literature of relevance previously known by the researchers was also considered. The selection of eligible literature is shown in , and the included literature is presented as references and summarized in and .

FIGURE 2. Flow diagram for the literature selection.

From: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

TABLE 1. The identified problems in the performance of investigations of patient harm applicable to suicide cases, along with evidence.

TABLE 2. Changes in the performance of investigations of suicide cases to address the problems in investigations of patient harm, along with evidence. The changes are interlinked and there is sometimes no sharp separation between them. Actions within one area can be expected to raise improvement in others as well.

The literature was split into two themes in accordance with the main study questions: (1) problems with current approaches to investigations and (2) support for changes to address the identified problems. Some papers included material relevant to both questions, in which case, we identified specific sections relevant to each theme. In each paper, potentially relevant issues were identified by EF in discussion with the other authors. Relevant issues were then grouped and categorized by EF. These categories were reviewed and revised by the research group until a consensus was reached. The final categories provided a framework for this study.

RESULTS

The literature on investigations of suicide as incidents of patient harm is sparse. The included studies originated from Europe, North America, and Australia.

Problems with Current Approaches to Investigations

The literature on investigations and our own recently published review of investigations of healthcare regarding suicides in Sweden (Fröding et al., Citation2021) revealed several weaknesses in the current approaches. These cast doubt on the findings of investigations and limit the scope and nature of the actions taken to reduce suicide. We summarize the main problems below and in , which provides the foundation for the following section on how to move forward.

Failure to Embrace the Perspective of the Patient and Family

Reports of investigations in England showed a lack of perspectives from the patient or their family on the incident (Care Quality Commission, Citation2016) and that involvement of the family in the investigation process could meet resistance from professionals (de Kam et al., Citation2020; Fortin et al., Citation2021). Reviews of suicide investigations of healthcare showed that many did not seriously attempt to understand the experiences of the patient or the perspective of the family (Fröding et al., Citation2021; Vine & Mulder, Citation2013).

Not Addressing All Relevant Factors

Analysis of variables of significance for suicidal behavior, such as risk factors, suicide reducing interventions, and care availability, is a critical part of any suicide investigation (Janofsky, Citation2009; Vine & Mulder, Citation2013; Vrklevski, McKechnie, & OʼConnor, Citation2018). However, our previous review showed that investigations of healthcare did not include an analysis of prior suicidality or suicide attempts (Fröding et al., Citation2021). The investigations were more adapted to responding to the supervisory authority than understanding the complex web of causes and conditions that led to the eventual suicide (Fröding et al., Citation2021).

A Short Timeframe for Analysis

People who take their lives usually suffer from a long period of decline. However, investigations usually focused on a relatively brief, defined period before the suicide or on the last contacts with healthcare before an incident (Fröding et al., Citation2021; Nicolini, Waring, & Mengis, Citation2011b). Any analysis that focuses only on the last contacts with healthcare will fail to uncover progressive degradations in care over time and equally fail to appreciate past care that was supportive and positive (Leistikow et al., Citation2017; Vincent et al., Citation2017).

Investigations Focus Are Too Narrowly Focused on One Healthcare Provider

Our previous reviews of investigations of healthcare before suicide showed that deficiencies in coordination between providers were pointed out as contributory to suicide incidents in almost one-third of cases. However, most investigations were performed by a local leader within a single unit (the last unit caring for the patient), without the involvement of other healthcare providers (Fröding et al., Citation2021; Roos af Hjelmsäter et al., Citation2019).

Failure to Consider a Deeper System Perspective

Investigators tended to finalize their analyses after identifying human error, rather than proceeding to identify wider organizational and system problems (Mills et al., Citation2006; Percarpio et al., Citation2008). This narrow focus on individual failures inevitably leads to inadequate solutions and recommendations (Nicolini, Waring, & Mengis, Citation2011b). Investigators recommend narrow administrative interventions, such as reminders or new routines, rather than those that address the deeper underlying problems (Fröding et al., Citation2021; Wrigstad, Bergström, & Gustafson, Citation2014). Furthermore, the investigations report one case at a time, and the learning stays within the local units (Roos af Hjelmsäter et al., Citation2019).

The Experience and Expertise of the Investigation Team

There are wide differences in experience and competence within investigation teams, leading to variations in performance and approaches to investigations (Macrae, Citation2014a, Citation2014b; Macrae, Citation2016; Nicolini, Waring, & Mengis, Citation2011b; Wu, Lipshutz, & Pronovost, Citation2008). Patients who take their lives are often in contact with multiple services, and yet the investigation teams often lack important clinical perspectives, with the absence of doctors being a particular problem (Elfström, Citation2009; Nicolini, Waring, & Mengis, Citation2011a; Roos af Hjelmsäter et al., Citation2019; Woloshynowych et al., Citation2005).

Moving Forward

Therefore, we suggest major changes in the performance of investigations to address the identified problems, as summarized in . These issues are interlinked, and sometimes there is no sharp separation between them. Involving the family, for instance, will invariably expand the scope and time scale of the investigation.

Understand the Perspectives of the Patient

The involved patient is central in an incident of patient harm, and if preventive suicide care is to be successful, investigators have to endeavor to understand the resources and needs of the suicidal individual (Vrklevski, McKechnie, & OʼConnor, Citation2018). Individual factors, personality, life circumstances, and motivators are of great significance and relevance in the progress of suicidal behavior. After a suicide, the analysis of care through the patient’s eyes is challenging. However, conscious intentional efforts to shift the perspective of the analysis from the provider’s perspective to explore how the healthcare systems managed to meet the expectations and needs of the patient should provide some insights.

Family, carers, and significant others usually know more about the patient and their connections to healthcare compared to the healthcare staff. Their contributions to the analysis should broaden and deepen our understanding of patients’ experiences. Studies on the involvement of patients and/or families in incident analyses have shown contributions of new perspectives to the analyses and identification of adverse events not detected by professionals (Bouwman et al., Citation2018; Lang, Garrido, & Heintze, Citation2016; O’Hara et al., Citation2018; Van Tilburg et al., Citation2006; Weissman et al., Citation2008; Wiig et al., Citation2021; Zimmerman & Amori, Citation2007).

Furthermore, safety in the care of suicidal patients is broader than technical terms and the views of healthcare stakeholders. Perceived connections to professionals, senses of protection, and control of their lives are highly important for suicidal patients’ experiences of safety in healthcare (Berg, Rortveit, & Aase, Citation2017). Efforts to analyze how healthcare managed to meet the expectations and needs through the lens of the patient should introduce perspectives that would be useful in understanding, learning, and improving healthcare and patient safety (Vincent & Amalberti, Citation2016).

Integrate Variables of Significance for Suicide Behavior, Prevention and Safety

Several factors influencing suicidality are now known and available for modification through evidence-based suicide reduction strategies (Klonsky et al., Citation2021; Mann, Michel, & Auerbach, Citation2021; O’Connor & Nock, Citation2014). Integration of these variables, such as risk factors and triggers, into investigations should improve the possibilities of understanding the essentials of the underlying individual process of suicidal behavior (Vine & Mulder, Citation2013). Analysis of performed and/or possible interventions of current influencing factors is crucial in the analysis of risk management over time and raises the possibility of finding improvements in work with suicide prevention and patient safety (Vrklevski, McKechnie, & OʼConnor, Citation2018).

Learn from Recoveries and Periods of Stability

Integration of theories of Safety-II in analyses: learning from performance of daily work and from all that goes well, successes, and recoveries, as well as from failures and close calls, should bring new valuable perspectives (Braithwaite et al., Citation2015; Leistikow et al., Citation2017; Vincent & Amalberti, Citation2016; Wu & Marks, Citation2013). Attention to episodes of successful recovery from acute suicide crises or suicide attempts could have implications for the understanding of individual recovery strategies and how healthcare management can cope with individual needs and factors significant for improving suicide prevention in healthcare (Bowers et al., Citation2011). Furthermore, analysis of periods of stability could reveal individual adaptive strategies and knowledge of factors significant for the preservation of health and wellbeing (Vincent et al., Citation2017).

Widen the Perspective of Time

The investigations should analyze all the relevant factors leading to eventual suicide, not just the healthcare received or not received. Therefore, the analysis must start from the beginning of suicidality and embrace the entire suicide process with fluctuations in intensity to enable an understanding of the current interacting factors. Failures of longer courses of care are often marked by an accumulation and combination of problems, errors, and system vulnerabilities over time, and to uncover potential progressive degradation in care, the analysis must span longer periods (Barker, Steventon, & Deeny, Citation2017; Hutchinson et al., Citation2010; Vincent & Amalberti, Citation2016; Vincent et al., Citation2017).

Widen the System Perspective

Involve current healthcare providers, family, and carers, and other significant persons in the investigations to understand the whole picture. Healthcare staff members are only involved in the care performed at their own units and know about these specific episodes. Investigations need to embrace all relevant contexts across organizations, including the home, community environment, and social service. The high volume of mental outpatient care and the need for collaboration and communication across the continuum of care raise considerations of the transitions between care providers and potential errors in outpatient settings. These wider interdependencies have seldom been addressed in local investigations (Dixon-Woods & Pronovost, Citation2016).

Family, carers, and other significant persons for the patient, social workers, staff at school or job, employers, local authorities, or judicial system are all potentially relevant informants who could shed light on the person’s life outside the healthcare (Zimmerman & Amori, Citation2007), where most people spend the main part of their lives.

External Investigation Leaders with Expertise in Incident Analysis and Healthcare

Ideally, leaders of the investigation should be external and independent of the units involved. Local investigators might be under the influence of hierarchical tensions and hence endeavor to preserve interpersonal relationships, which may compromise the depth and accuracy of the analysis with a focus on what is possible rather than what is needed (Macrae & Vincent, Citation2014; Nicolini, Waring, & Mengis, Citation2011a, Citation2011b). Further, investigation leaders need substantial competence and experience in the chosen investigation method and patient safety to ensure sufficient quality in the investigation (Macrae, Citation2016; Macrae & Vincent, Citation2014; Peerally et al., Citation2017; Vincent & Amalberti, Citation2015, Citation2016; Vincent et al., Citation2017; Woloshynowych et al., Citation2005).

Multidisciplinary Analysis Teams with Expertise in Suicidology and Broad Competence in Healthcare Services

The analysis teams should be multidisciplinary with specific expertise in suicidology and broad competence in healthcare services to enable analyses covering all adequate aspects of care (Pham et al., Citation2010; Vrklevski, McKechnie, & OʼConnor, Citation2018). Besides professional expertise, knowledge of the local conditions and policies is needed to manage the careful and inter-professional considerations of care at all levels that are needed to find meaningful actions at severe patient harms.

DISCUSSION

Several weaknesses in current approaches to investigations of healthcare at suicide have been identified, raising doubts about the effectiveness of current approaches. To become an effective and valuable tool for improving healthcare in the cases of suicidality, investigation methods must reflect the progress of knowledge about suicidal behavior, suicide prevention, and patient safety. This includes embracing the patient’s perspective, professionalization of investigations, analyses across organizational boundaries, and focus on learning and improvement. To support this, there is a need for substantial changes in the investigation approaches (). We see the need for a paradigm shift in the approaches to investigations of suicide. Actions are needed on multiple levels, along with support, recommendations, and requirements from authorities, healthcare providers, researchers, and stakeholders.

TABLE 3. Six major steps to make investigations of suicide valuable for learning and prevention.

Implications for Policies and Clinical Practice

We suggest six actions of importance:

Involvement of families in the analyses should become the default option, with the important proviso of considering psychological and emotional timeliness. New approaches in the analysis process and the capability to manage meetings are needed to allow the inclusion of patient perspectives without burdening the family unduly.

Select and conduct proportionate analyses. The deep, long-term investigations across organizations that we suggest in this paper are resource-intensive. A triage system regarding the depth and extent of the analyses proportional to the value of learning and improvement, particularly in terms of the likely revealing problems not highlighted in current systems, and is needed to support which cases should be selected for extensive analysis.

Education and training for investigator expertise. Investigation leaders are critical in ensuring a thorough and professional investigation. To meet this need, substantial efforts in education and training in incident analysis for healthcare professionals are needed. Fewer investigators should conduct further investigations to build up and maintain expertise.

Multidisciplinary analysis teams with competence in and authorized access to relevant organizations. Infrastructures supporting data sharing, collaborative analysis, and coordinated improvement across organizational boundaries are needed, along with appropriate legal frameworks.

Aggregation of data. Generating learning and recommendations for actions based on a single incident may be delicate and even risky for patient safety. Instead, aggregation of the outcomes of suicide analyses, together with other related quality and safety data, should allow the analysis of major system issues and insights into more meaningful action plans. A regional or national data-base could be one way to meet this requirement.

A new model for investigation of suicide cases based on the results of this study could facilitate this paradigm shift. The model should serve as a framework for how investigations should be performed and guide the analysis of the significant parts and perspectives described above. We are currently working on these models.

Challenges of Implementation

We realize that there are challenges in managing our suggested approaches, and adaptations are required in relation to different contexts.

First, healthcare providers’ resources for investing in investigations are limited. To optimize the benefits, efforts to ensure investigations of high quality and exploration of how the selection of cases for extensive analyses is to be made should be prioritized.

Second, the performance of interactive investigations with families can meet the resistance of professionals (de Kam et al., Citation2020; Fortin et al., Citation2021). Healthcare managers and investigation leaders, in particular, have a significant role in influencing the culture of this issue (Zimmerman & Amori, Citation2007). The involvement requires careful professional respect for both the patient and involved staff and awareness of the psychological impact the analysis can have on all involved. Similarly, analysis across organizations requires the development of norms and social agreements to collaborate and share information across boundaries. Furthermore, ethical and legal frameworks must be considered.

Finally, research and investment in the testing, development, and evaluation of current and new approaches of healthcare analyses are required for progress in learning and improvement in patient safety. Systematic nationwide efforts to aggregate information on all suicides among persons who have been in contact with mental healthcare and/or addiction services during the year before death have been effectuated for several years in Norway (National Center for Suicide Research and Prevention) and the UK (The National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Safety in Mental Health, NCISH). These initiatives have resulted in several publications available on their websites (National Centre for Suicide Research and Prevention, Citation2022; National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Safety in Mental Health, 2022). Standards for investigating serious incidents suggested by NCISH, such as independent investigators, contact with family, access to full case records, and action plans (National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Homicide by People with Mental Illness, Citation2022), and the proposal to improve safety in mental health services by creating a learning culture based on multidisciplinary reviews (National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Homicide by People with Mental Illness, Citation2013) are in line with our suggested changes and implications.

This study focused on the investigation of care during suicide incidents, but the findings and proposals may be relevant to cases of patient harm for other chronic diseases.

Strengths and Limitations

The combination of clinical and academic experiences in suicidology, patient safety and healthcare improvement in the research team served as strengths in this study, facilitating the evaluation and application of the literature. However, this study has several limitations that must be considered in the interpretation of the results.

One limitation of this study was the researchers’ preunderstanding and experience in the research field, risking unintentional reviewer bias. Owing to a lack of common nomenclature in the relevant science fields, there was a risk that studies of relevance might be missed in the literature search. To address these limitations, the search strategy was developed in consultation with a professional university librarian. Furthermore, this study did not include systematic searches of gray literature.

The literature specific to investigations of suicide as incidents of patient harm is sparse. However, to the best of our knowledge, all included studies were applicable and significant for the investigation of suicide cases.

This study aimed to review investigations of suicide as incidents of patient harm, not representing suicides in the general population.

CONCLUSIONS

There are several problems in the current approaches to investigating suicide as incidents of patient harm. The progress in knowledge about suicidal behavior, suicide prevention, and patient safety should be reflected in the improvement of these investigations.

To move forward, a paradigm shift in the investigation approaches is needed. This includes embracing the patient’s perspective, professionalization of investigations, analyses across organizational boundaries, and focus on learning and improvement.

Actions to manage this paradigm shift include involvement of patients and families, education and training for investigators, and multidisciplinary analysis teams with competence in and access to relevant parts across organizations. A triage of cases for extensive analyses, with expected substantial learning and insights valuable for healthcare improvement, is necessary.

A new model for investigating suicide as a potential patient harm based on the results of this study should facilitate this paradigm shift.

Based on the results of this review, we are working on a model for investigating suicide as a potential patient harm. The model was co-designed with persons with their own experiences of suicidality and healthcare, and with professionals. The model will shortly be tested and evaluated iteratively to refine and make it adaptable to different contexts and situations.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are grateful to Region Jönköpings County and Futurum, the academy for health and care, for funding. We thank the librarians for their support in the development of the research methodology.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

E. Fröding

E. Fröding, Jönköping University and Region Jönköping County, Jönköping, Sweden.

C. Vincent

C. Vincent, Department of Experimental Psychology, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom.

B. Andersson-Gäre

B. Andersson-Gäre, Futurum, Region Jönköping County, and Jönköping Academy for Improvement of Health and Welfare, Jönköping University, Jönköping, Sweden.

Å. Westrin

Å. Westrin, Department of Clinical Sciences Lund, Psychiatry, Lund University, and Office for Psychiatry and Habilitation, Psychiatry Research Skåne, Region Skåne, Lund, Sweden.

A. Ros

A. Ros Futurum, Region Jönköping County, and Jönköping Academy for Improvement of Health and Welfare, Jönköping University, Jönköping, Sweden.

REFERENCES

- Ahmedani, B. K., Westphal, J., Autio, K., Elsiss, F., Peterson, E. L., Beck, A., … Lynch, F. (2019). Variation in patterns of health care before suicide: A population case-control study. Preventive Medicine, 127, 105796.

- Anderson, J. E., Kodate, N., Walters, R., & Dodds, A. (2013). Can incident reporting improve safety? Healthcare practitioners’ views of the effectiveness of incident reporting. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 25(2), 141–150. 10.1093/intqhc/mzs081

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. doi:10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Barker, I., Steventon, A., & Deeny, S. R. (2017). Association between continuity of care in general practice and hospital admissions for ambulatory care sensitive conditions: Cross sectional study of routinely collected, person level data. BMJ 356, j84. doi:10.1136/bmj.j84

- Bates, D. W., & Singh, H. (2018). Two decades since to err is human: An assessment of progress and emerging priorities in patient safety. Health Affairs, 37(11), 1736–1743. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2018.0738

- Berg, S. H., Rortveit, K., & Aase, K. (2017). Suicidal patients’ experiences regarding their safety during psychiatric in-patient care: A systematic review of qualitative studies. BMC Health Services Research, 17(1), 73. doi:10.1186/s12913-017-2023-8

- Berg, S. H., Rørtveit, K., Walby, F. A., & Aase, K. (2020). Safe clinical practice for patients hospitalised in mental health wards during a suicidal crisis: Qualitative study of patient experiences. BMJ Open, 10(11), e040088. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-040088

- Bergqvist, E., Probert-Lindström, S., Fröding, E., Palmqvist-Öberg, N., Ehnvall, A., Sunnqvist, C., … Westrin, Å. (2022). Health care utilisation two years prior to suicide in Sweden: A retrospective explorative study based on medical records. BMC Health Services Research, 22(1), 1–10. doi:10.1186/s12913-022-08044-9

- Bouwman, R., de Graaff, B., de Beurs, D., van de Bovenkamp, H., Leistikow, I., & Friele, R. (2018). Involving patients and families in the analysis of suicides, suicide attempts, and other sentinel events in mental healthcare: A qualitative study in The Netherlands. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(6), 1104. doi:10.3390/ijerph15061104

- Bowers, L., Dack, C., Gul, N., Thomas, B., & James, K. (2011). Learning from prevented suicide in psychiatric inpatient care: An analysis of data from the National Patient Safety Agency. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 48(12), 1459–1465. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.05.008

- Braithwaite, J., Wears, R. L., & Hollnagel, E. (2015). Resilient health care: Turning patient safety on its head. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 27(5), 418–420. 10.1093/intqhc/mzv063

- Care Quality Commission. (2016). Learning from serious incidents in NHS acute hospitals. A review of the quality of investigation reports. Stratford: Care Quality Commission.

- Chock, M. M., Lin, J. C., Athyal, V. P., & Bostwick, J. M. (2019). Differences in health care utilization in the year before suicide death: A population-based case-control ctudy. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 94(10), 1983–1993. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.04.037

- de Kam, D., Kok, J., Grit, K., Leistikow, I., Vlemminx, M., & Bal, R. (2020). How incident reporting systems can stimulate social and participative learning: A mixed-methods study. Health Policy, 124(8), 834–841. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2020.05.018

- Dixon-Woods, M., & Pronovost, P. J. (2016). Patient safety and the problem of many hands. BMJ Quality & Safety, 25(7), 485–488. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2016-005232

- Doupnik, S. K., Rudd, B., Schmutte, T., Worsley, D., Bowden, C. F., McCarthy, E., … Marcus, S. C. (2020). Association of suicide prevention interventions with subsequent suicide attempts, linkage to follow-up care, and depression symptoms for acute care settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry, 77(10), 1021–1030. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1586

- Elfström, J. (2009). [Incident analyses in healthcare should be sharpened and involve physicians]. Lakartidningen, 48/2009.

- Fortin, G., Ligier, F., Van Haaster, I., Doyon, C., Daneau, D., & Lesage, A. (2021). Systematic suicide audit: An enhanced method to assess system gaps and Mobilize leaders for prevention. Quality Management in Health Care, 30(2), 97–103. 10.1097/qmh.0000000000000302

- Fröding, E., Gäre, B. A., Westrin, Å., & Ros, A. (2021). Suicide as an incident of severe patient harm: A retrospective cohort study of investigations after suicide in Swedish healthcare in a 13-year perspective. BMJ Open, 11(3), e044068. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-044068

- Gillies, D., Chicop, D., & O’Halloran, P. (2015). Root cause analyses of suicides of mental health clients. Crisis, 36(5), 316–324. doi:10.1027/0227-5910/a000328

- Hagley, G., Mills, P. D., Watts, B. V., & Wu, A. W. (2019). Review of alternatives to root cause analysis: Developing a robust system for incident report analysis. BMJ Open Quality, 8(3), e000646.

- Hawton, K., Appleby, L., Platt, S., Foster, T., Cooper, J., Malmberg, A., & Simkin, S. (1998). The psychological autopsy approach to studying suicide: A review of methodological issues. Journal of Affective Disorders, 50(2–3), 269–276.

- Hawton, K., & Pirkis, J. (2017). Suicide is a complex problem that requires a range of prevention initiatives and methods of evaluation. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 210(6), 381–383.

- Hawton, K., & van Heeringen, K. (2009). Suicide. Lancet, 373(9672), 1372–1381. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60372-X

- Hofstra, E., Van Nieuwenhuizen, C., Bakker, M., Özgül, D., Elfeddali, I., de Jong, S. J., & van der Feltz-Cornelis, C. M. (2020). Effectiveness of suicide prevention interventions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. General Hospital Psychiatry, 63, 127–140. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2019.04.011

- Hollnagel, E., Wears, R. L., & Braithwaite, J. (2015). From Safety-I to Safety-II: A white paper. Published simultaneously by the University of Southern Denmark. Australia: University of Florida, USA, and Macquarie University, Australia: The Resilient Health Care Net.

- Hutchinson, A., Coster, J., Cooper, K., McIntosh, A., Walters, S., Bath, P., … Nicholl, J. (2010). Assessing quality of care from hospital case notes: Comparison of reliability of two methods. Quality and Safety in Health Care, 19(6), e2–e2.

- Ishimo, M.-C., Sampasa-Kanyinga, H., Olibris, B., Chawla, M., Berfeld, N., Prince, S. A., … Lang, J. J. (2021). Universal interventions for suicide prevention in high-income Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) member countries: A systematic review. Injury Prevention, 27(2), 184–193. doi:10.1136/injuryprev-2020-043975

- Isometsä, E. (2001). Psychological autopsy studies–a review. European Psychiatry, 16(7), 379–385. doi:10.1016/S0924-9338(01)00594-6

- Janofsky, J. S. (2009). Reducing inpatient suicide risk: Using human factors analysis to improve observation practices. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law Online, 37(1), 15–24.

- Klonsky, E. D., & May, A. M. (2015). The three-step theory (3ST): A new theory of suicide rooted in the “ideation-to-action” framework. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 8(2), 114–129. doi:10.1521/ijct.2015.8.2.114

- Klonsky, E. D., Pachkowski, M. C., Shahnaz, A., & May, A. M. (2021). The three-step theory of suicide: Description, evidence, and some useful points of clarification. Preventive Medicine, 152(Pt 1), 106549.

- Lang, S., Garrido, M. V., & Heintze, C. (2016). Patients’ views of adverse events in primary and ambulatory care: A systematic review to assess methods and the content of what patients consider to be adverse events. BMC Family Practice, 17(1), 6–9.

- Leape, L. L. (2002). Reporting of adverse events. The New England Journal of Medicine, 347(20), 1633–1638. 10.1056/NEJMNEJMhpr011493

- Leistikow, I., Mulder, S., Vesseur, J., & Robben, P. (2017). Learning from incidents in healthcare: The journey, not the arrival, matters. BMJ Quality & Safety, 26(3), 252–256. 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004853

- Macrae, C. (2014a). Close calls: Managing risk and resilience in airline flight safety. Verlag: Springer.

- Macrae, C. (2014b). Early warnings, weak signals and learning from healthcare disasters. BMJ Quality & Safety, 23(6), 440–445. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002685

- Macrae, C. (2016). The problem with incident reporting. BMJ Quality & Safety, 25(2), 71–75. 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004732

- Macrae, C., & Vincent, C. (2014). Learning from failure: The need for independent safety investigation in healthcare. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 107(11), 439–443. 10.1177/0141076814555939

- Mann, J., & Currier, D. (2010). Stress, genetics and epigenetic effects on the neurobiology of suicidal behavior and depression. European Psychiatry, 25(5), 268–271.

- Mann, J. J., Michel, C. A., & Auerbach, R. P. (2021). Improving suicide prevention through evidence-based strategies: A systematic review. American Journal of Psychiatry, 178(7), 611–624. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20060864

- Mills, P. D., Neily, J., Luan, D., Osborne, A., & Howard, K. (2006). Actions and implementation strategies to reduce suicidal events in the Veterans Health Administration. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 32(3), 130–141.

- Mitchell, I., Schuster, A., Smith, K., Pronovost, P., & Wu, A. (2016). Patient safety incident reporting: A qualitative study of thoughts and perceptions of experts 15 years after ‘To Err is Human’. BMJ Quality & Safety, 25(2), 92–99. 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004405

- National Centre for Suicide Research and Prevention. (2022). University of Oslo. Retrieved July 8 from https://www.med.uio.no/klinmed/english/research/centres/nssf/.

- National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Homicide by People with Mental Illness. (2013). Patient suicide: The impact of service changes. A UK wide study. UK: T. U. o. Manchester.

- National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Homicide by People with Mental Illness. (2022). NCISH 10 standards for investigating serious incidents. The University of Manchester. Retrieved July 8 from https://sites.manchester.ac.uk/ncish/resources/ncish-10-standards-for-investigating-serious-incidents/.

- National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Safety in Mental Health. (2022). The University of Manchester,. Retrieved July 8 from. https://sites.manchester.ac.uk/ncish/.

- National Institute for Health and Welfare. (2009). National reporting systems for patient safety incidents. A review of the situation in Europe. Helsinki: NIHW.

- Neal, L. A., Watson, D., Hicks, T., Porter, M., & Hill, D. (2004). Root cause analysis applied to the investigation of serious untoward incidents in mental health services. Psychiatric Bulletin, 28(3), 75–77. doi:10.1192/pb.28.3.75

- Ngwena, J., Hosany, Z., & Sibindi, I. (2017). Suicide: A concept analysis. Journal of Public Health, 25(2), 123–134. doi:10.1007/s10389-016-0768-x

- Nicolini, D., Waring, J., & Mengis, J. (2011a). The challenges of undertaking root cause analysis in health care: A qualitative study. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 16(1_suppl), 34–41. doi:10.1258/jhsrp.2010.010092

- Nicolini, D., Waring, J., & Mengis, J. (2011b). Policy and practice in the use of root cause analysis to investigate clinical adverse events: Mind the gap. Social Science & Medicine, 73(2), 217–225. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.05.010

- Nock, M. K., Borges, G., Bromet, E. J., Cha, C. B., Kessler, R. C., & Lee, S. (2008). Suicide and suicidal behavior. Epidemiologic Reviews, 30(1), 133–154. 10.1093/epirev/mxn002

- O’Connor, R. C., & Kirtley, O. J. (2018). The integrated motivational–volitional model of suicidal behaviour. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 373(1754), 20170268. doi:10.1098/rstb.2017.0268

- O'Connor, R. C., & Nock, M. K. (2014). The psychology of suicidal behaviour. The Lancet Psychiatry, 1(1), 73–85. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70222-6

- O’Connor, R. C. (2011). Towards an integrated motivational–volitional model of suicidal behaviour. International Handbook of Suicide Prevention, 1, 181–198.

- O’Hara, J. K., Reynolds, C., Moore, S., Armitage, G., Sheard, L., Marsh, C., … Lawton, R. (2018). What can patients tell us about the quality and safety of hospital care? Findings from a UK multicentre survey study. BMJ Quality & Safety, 27(9), 673–682.

- Peerally, M. F., Carr, S., Waring, J., & Dixon-Woods, M. (2017). The problem with root cause analysis. BMJ Quality & Safety, 26(5), 417–422. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2016-005511

- Percarpio, K. B., Watts, B. V., & Weeks, W. B. (2008). The effectiveness of root cause analysis: What does the literature tell us? Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 34(7), 391–398. doi:10.1016/S1553-7250(08)34049-5

- Pham, J. C., Kim, G. R., Natterman, J. P., Cover, R. M., Goeschel, C. A., Wu, A. W., & Pronovost, P. J. (2010). ReCASTing the RCA: An improved model for performing root cause analyses. American Journal of Medical Quality, 25(3), 186–191.

- Rajendran, S., Mills, P. D., Watts, B. V., & Gunnar, W. (2022). Suicide and suicide attempts on Veterans Affairs medical center outpatient clinic areas, common areas, and hospital grounds. Journal of Patient Safety, 18(1), 33–39. 10.1097/PTS.0000000000000796

- Roos af Hjelmsäter, E., Ros, A., Gäre, B. A., & Westrin, Å. (2019). Deficiencies in healthcare prior to suicide and actions to deal with them: A retrospective study of investigations after suicide in Swedish healthcare. BMJ Open, 9(12), e032290. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-032290

- Rudd, M. D. (2006). Fluid vulnerability theory: A cognitive approach to understanding the process of acute and chronic suicide risk. In Cognition and suicide: Theory, research, and therapy (pp. 355–368). Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association.

- Shojania, K. G., & Thomas, E. J. (2013). Trends in adverse events over time: Why are we not improving? BMJ Quality & Safety, 22(4), 273–277. 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-001935

- Stene-Larsen, K., & Reneflot, A. (2019). Contact with primary and mental health care prior to suicide: A systematic review of the literature from 2000 to 2017. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 47(1), 9–17. doi:10.1177/1403494817746274

- Trbovich, P., & Shojania, K. G. (2017). Root-cause analysis: Swatting at mosquitoes versus draining the swamp. BMJ Quality & Safety, 26(5), 350–353. 10.1136/bmjqs-2016-006229

- Turecki, G., & Brent, D. A. (2016). Suicide and suicidal behaviour. The Lancet, 387(10024), 1227–1239. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00234-2

- Turecki, G., Brent, D. A., Gunnell, D., O’Connor, R. C., Oquendo, M. A., Pirkis, J., & Stanley, B. H. (2019). Suicide and suicide risk. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 5(1), 1–22. doi:10.1038/s41572-019-0121-0

- van Heeringen, K., & Mann, J. J. (2014). The neurobiology of suicide. The Lancet. Psychiatry, 1(1), 63–72. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70220-2

- Van Tilburg, C., Leistikow, I., Rademaker, C., Bierings, M., & Van Dijk, A. (2006). Health care failure mode and effect analysis: A useful proactive risk analysis in a pediatric oncology ward. Quality and Safety in Health Care, 15(1), 58–63. doi:10.1136/qshc.2005.014902

- Vincent, C. (2003). Understanding and responding to adverse events. The New England Journal of Medicine, 348(11), 1051–1056. 10.1056/NEJMhpr020760

- Vincent, C., & Amalberti, R. (2015). Safety in healthcare is a moving target. BMJ Quality & Safety, 24(9), 539–540. 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004403

- Vincent, C., & Amalberti, R. (2016). Safer Healthcare: Strategies for the Real World. Cham: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-25559-0

- Vincent, C., Carthey, J., Macrae, C., & Amalberti, R. (2017). Safety analysis over time: Seven major changes to adverse event investigation. Implementation Science, 12(1), 151. 10.1186/s13012-017-0695-4

- Vine, R., & Mulder, C. (2013). After an inpatient suicide: The aim and outcome of review mechanisms. Australasian Psychiatry, 21(4), 359–364.

- Vrklevski, L. P., McKechnie, L., & OʼConnor, N. (2018). The causes of their death appear (unto our shame perpetual): Why root cause analysis is not the best model for error investigation in mental health services. Journal of Patient Safety, 14(1), 41–48. doi:10.1097/PTS.0000000000000169

- Weissman, J. S., Schneider, E. C., Weingart, S. N., Epstein, A. M., David-Kasdan, J., Feibelmann, S., … Gatsonis, C. (2008). Comparing patient-reported hospital adverse events with medical record review: Do patients know something that hospitals do not? Annals of Internal Medicine, 149(2), 100–108.

- Wiig, S., Schibevaag, L., Zachrisen, R. T., Hannisdal, E., Anderson, J. E., & Haraldseid-Driftland, C. (2021). Next-of-kin involvement in regulatory investigations of adverse events that caused patient death: A process evaluation (part II: The inspectors’ perspective). Journal of Patient Safety, 17(8), e1707–e1712.

- Woloshynowych, M., Rogers, S., Taylor-Adams, S., & Vincent, C. (2005). The investigation and analysis of critical incidents and adverse events in healthcare. Health Technology Assessment, 9(19), 1–143, iii. doi:10.3310/hta9190

- World Health Organization. (2021). Suicide. Retrieved January 13 from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/suicide.

- World Health Organization. (2022). Patient safety. Retrieved March 23 2022 from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/patient-safety.

- Wrigstad, J., Bergström, J., & Gustafson, P. (2014). Mind the gap between recommendation and implementation—principles and lessons in the aftermath of incident investigations: A semi-quantitative and qualitative study of factors leading to the successful implementation of recommendations. BMJ Open, 4(5), e005326. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005326

- Wu, A. W., Lipshutz, A. K., & Pronovost, P. J. (2008). Effectiveness and efficiency of root cause analysis in medicine. JAMA, 299(6), 685–687. 10.1001/jama.299.6.685

- Wu, A. W., & Marks, C. M. (2013). Close calls in patient safety: Should we be paying closer attention? Canadian Medical Association Journal = Journal de L'Association Medicale Canadienne, 185(13), 1119–1120.

- Zimmerman, T. M., & Amori, G. (2007). Including patients in root cause and system failure analysis: Legal and psychological implications. Journal of Healthcare Risk Management, 27(2), 27–34.