Abstract

Background

In most countries, men complete suicide at twice the rate of women; masculinity plays an important role in placing men at a greater risk of suicide. This study identifies and describes trends in the topics discussed within the masculinity and suicide literature and explores changes over time.

Methods

We retrieved publications relating to masculinity and suicide from eight electronic databases and described origins in the field of research by reference to the first decade of publications. We then explored the subsequent evolution of the field by analysis of the content of article titles/abstracts for all years since the topic first emerged, and then separately by three epochs.

Results

We included 452 publications (1954–2021); research output has grown substantially in the last five years. Early publications framed suicide in the context of severe mental illness, masculinity as a risk factor, and suicidality as being aggressive and masculine. We observed some differences in themes over time: Epoch 1 focused on sex differences in suicidality, a common theme in epochs 2 was relationship to work and its effect on men’s mental health and suicidality, and epoch 3 had a focus on help-seeking in suicidality.

Conclusion

The research field of masculinity and suicide is growing strongly, as evidenced by recent increase in publication volume. The structure, content and direction of the masculinity and suicide research are still evolving. Researchers must work with policymakers and practitioners to ensure that emerging findings are translated for use in programs designed to address suicide in boys and men.

Masculinity and suicide as a field is not new, with its origins in the literature dating back to 1954.

More than half of the total research output in the field (1954–2021) has been published in the last five years.

Early work focused on individual-level risk factors to male suicide (e.g., severe mental illness), while contemporary research focused on social and cultural determinants of male suicide (e.g., help-seeking).

HIGHLIGHTS

INTRODUCTION

The World Health Organization estimates that over 700,000 people die by suicide every year (World Health Organization, Citation2021a, Citation2021b). In 2019, the global age-standardized suicide rate was more than double for males than females (12.6 vs 5.4 per 100,000 people, respectively), and this disparity holds true for most countries (World Health Organization, Citation2021a). Some explanations for this gender inequality in suicide rates have been proposed, including: (i) choice of method: compared with females, males tend to favor more lethal methods (Mergl et al., Citation2015); (ii) differences in risk factors: the prevalence of alcohol and drug use is higher amongst males than females (Pompili et al., Citation2010; Schneider, Citation2009), and (iii) help-seeking behavior: males are less likely than females to seek help in times of difficulty (Möller-Leimkühler, Citation2002). It is also plausible that masculinity—the socially constructed cultural ideal that tells boys and men how they should think, feel, and behave (Connell & Messerschmidt, Citation2005; Levant & Pryor, Citation2020)—may underpin these factors that put men at a greater risk of suicide.

As masculinity is culturally constructed, there are several masculinities, even within individual societies (Levant & Pryor, Citation2020). Therefore, masculinity is a heterogenous construct with multiple dimensions (Pirkis, Spittal, Keogh, Mousaferiadis, & Currier, Citation2017). For example, one of the most cited scales measuring conformity to masculine norms—the “Conformity to Masculine Norms Inventory”—has validated 11 dimensions: winning, emotional control, risk-taking, violence, dominance, playboy, self-reliance, primacy of work, power over women, disdain for homosexuals, and pursuit of status (Mahalik et al., Citation2003). However, it appears that only certain dimensions of masculinity are harmful in terms of being linked to suicidal behavior and/or major suicide risk factors (Cleary, Citation2012). Those harmful dimensions of masculinity, at least in Western societies, are those that define manhood narrowly and traditionally, emphasizing strength, stoicism, and attributing the expression of emotions to weakness (Cleary, Citation2019); a 2017 meta-analysis (78 samples; 19,453 participants) (Wong, Ho, Wang, & Miller, Citation2017) reported conformity to traditional masculine norms such as self-reliance, power over women, and playboy as being robustly associated with poor mental health, a major risk factor for suicide (San Too et al., Citation2019). Important mental health outcomes found to be related to adherence to these traditional masculine norms included depression, psychological distress/stress, substance use, body image problems, negative social functioning (e.g., loneliness), and less favorable attitudes toward seeking psychological help (Wong et al., Citation2017). Because social norms and values that influence concepts of masculinity and femininity change over time, there is value in tracking the research in line with these evolving social constructs.

Bibliometrics is defined as the body of research that explores units of publications, citations, and authorship within a field (Broadus, Citation1987). Bibliometric analyses provide a high-level overview of a field, highlighting trends over time by analyzing which publications, journals, authors, and organizations are the most influential. Further, they can identify and describe trends in the topics discussed in the literature, and how they may change over time. While previous bibliometric studies have mapped the broad suicide literature (Astraud, Bridge, & Jollant, Citation2020; Cai, Chang, & Yip, Citation2020), we are unaware of studies that have focused specifically on the confluence of masculinity and suicide. Thus, to take stock and inform future research, we aimed to address this important research gap through a bibliometric exploration of the origins and evolution of masculinity and suicide research.

We addressed our overall study aim through four objectives:

Objective 1: to identify and describe when the topic of masculinity first emerged in the suicide literature.

Objective 2: to identify how research output relating to masculinity and suicide has evolved over time.

Objective 3: to identify the major topics discussed within the masculinity and suicide literature, and whether they have changed over time.

Objective 4: to identify the most influential publications in masculinity and suicide research.

METHODS

Tools

We used a combination of manual database search, and plotting and inspection of publication trends over time. All work was conducted using Endnote (v20.1) (The EndNote Team, Citation2013), Microsoft Excel, R (v4.1.2) (R Core Team, Citation2021), and VOSviewer software (v1.6.17) (Eck & Waltman, Citation2009; Van Eck & Waltman, Citation2010).

VOSviewer is a freely available and widely used tool that allows the automation of bibliometric analyses; it was designed to create, visualize, and explore maps of complex network data (Van Eck & Waltman, Citation2013). VOSviewer has been used to characterize the literature in several health-related fields, including mental health (Chen et al., Citation2020; Xu et al., Citation2021), environmental health (Briganti, Delnevo, Brown, Hastings, & Steinberg, Citation2019), and digital health (Pai & Alathur, Citation2020).

Data Sources and Search Strategy

Suicide and masculinity research is cross-disciplinary, with research output found across medicine, allied health, public health, and the social sciences. For this reason, we developed a search strategy to capture the relevant literature as comprehensively as possible.

For objectives 1, 2, and 3, we searched Web of Science (WoS) Core Collection, Scopus, Embase (via Ovid), Academic Search Complete (via EBSCOhost), PsycInfo (via Ovid), Medline (via Ovid), SocINDEX (via EBSCOhost), and CINAHL (via EBSCOhost). The search syntax was developed and piloted for WoS (see Supplementary Table S1) and then translated for the other sources. The search strategy included free-text terms relating to masculinity and suicide in titles, abstracts, keywords, and controlled vocabulary subject headings (e.g., Medical Subject Headings, [MeSH] for Medline, and Emtree subject headings for Embase). The search was conducted from the inception of each database to 05 November 2021, and inclusion was limited to journal articles published in the English language. We imported the results of the searches into Endnote to allow duplicate publications to be removed. We then conducted a random check of 10% of the deduplicated data set to assess how well the search results matched our intended topic. Then, we iteratively refined and rechecked the search strategy to eliminate any obviously irrelevant publications.

For objective 4, we required access to citation data. We had ready access to two sources of multidisciplinary citation data (WoS and Scopus). Because there is no consensus on which database provides the greatest coverage (Pranckutė, Citation2021), we conducted pilot searches to identify which source would provide the best coverage of our topic. We determined that WoS had slightly greater coverage (4% more publications) than Scopus, and thus we used WoS source to retrieve the citation data. The WoS search syntax (see Supplementary Table S1) was identical to the search used for objectives 1, 2, and 3, including filters (journal articles, English language), with the exception that the citation data was retrieved on 18 December 2021.

Data Analyses

Objective 1: To Identify and Describe When the Topic of Masculinity First Emerged in the Suicide Literature

To characterize the origin of research in the field, we downloaded and manually assessed the earliest publications in the first decade of the literature. For each publication, we extracted authors names, publication year, country of publication, and aim of the study. We then summarized those publications to characterize the topics discussed in the earliest literature.

Objective 2: To Identify How Research Output Relating to Masculinity and Suicide Has Evolved over Time

To quantify output over time, we plotted and visually inspected the distribution of publications by year and the cumulative percentage of publications from 1954 to 2021.

Objective 3a: To Identify the Major Topics Discussed within the Masculinity and Suicide Literature

To identify the most prominent topics in the literature, we analyzed the co-occurrence of terms in the titles/abstracts of all publications’ years (1954–2021) using VOSviewer. Co-occurrence analysis is based on the number of publications in which terms occur together. The VOSviewer algorithm uses natural language processing to find terms as single nouns and/or compound nouns, such as masculinity/hegemonic masculinity, suicide/suicide prevention (Van Eck & Waltman, Citation2013), thus, counting compound nouns as a single term. The software uses distance-based bibliographic metrics, whereby the closer the distance between two terms on a network map, the more linked they are to each other. VOSviewer also color codes its clusters in the map within bubbles—with terms that co-occur more frequently having bigger bubbles (Van Eck & Waltman, Citation2010, Citation2011, Citation2013).

VOSviewer does not include common words such as pronouns, articles, and prepositions, and we merged terms that were synonyms (e.g., singular vs. plural forms; British vs. American spellings) or without any meaningful content (e.g., abstract, methods, results, data, date) from the analyses. Furthermore, when VOSviewer aggregates co-occurrences of terms in titles and abstracts, it shows the number of occurrences of a term and its relevance score (Van Eck & Waltman, Citation2011). The algorithm determines the most relevant terms by finding the distribution of (second-order) co-occurrences for each term and over all terms in the data set. Then these distributions are compared to each other. The greater the distance (as measured by the Kullback-Leibler distance), the larger the relevance of a term (Van Eck & Waltman, Citation2011). By default, the software shows 60% of the most relevant term in the network maps. We have also used the binary counting method (Van Eck & Waltman, Citation2013; presence vs absence of a term in a publication) in this analysis.

Objective 3b: To Explore If and How the Topics Discussed within the Masculinity and Suicide Literature Have Changed over Time

To explore the evolution of the field over time, we used discrete analysis epochs as per methods described elsewhere (Armfield et al., Citation2014). We initially considered dividing the data set into periods where there was a publication growth. However, due to low research activity until 2011 (fewer than 15 publications per year), we divided the corpus of publications into three equal epochs (based on the cumulative percentage), each representing one-third of the total published output. We imported each epoch’s publications separately into VOSviewer, and terms in titles/abstracts were counted using the binary counting method (Van Eck & Waltman, Citation2013)—presence vs absence of a term in a publication. We then imported the terms and number of occurrences to R and created word clouds for each. The word clouds were used to visualize the most prominent terms per epoch.

Objective 4: To Identify the Most Influential Publications in the Masculinity and Suicide Research

To identify the most influential publications, we downloaded citation data from the WoS database (see section “Data Sources and Search Strategy”, objective 4). We ranked the publications for their influence based on the average citations per year, as older publications have a greater window of opportunity to be cited than more recent publications.

RESULTS

Search Results

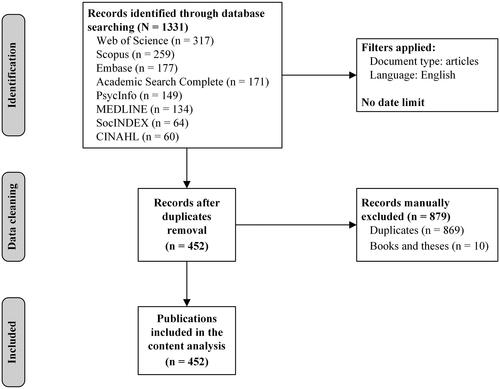

The search from the eight databases resulted in 1,331 publications. Ten publications were excluded as they were not journal articles (i.e., they were theses, books, and book sections). A further 869 publications were excluded as they were duplicates, leaving 452 publications for the analyses. Relevant fields, such as author(s), year of publication, journal name, title, abstract, and name of database, were exported for descriptive analyses. Out of 452 publications, 11 (2%) had missing data in the abstract field. We identified that the WoS database had the greatest number of publications across all databases, with 317 out of 1,331 (24%) publications before deduplication and 304 out of 452 (67%) publications after deduplication. See for a flow diagram for the identified records and results within each database.

Objective 1: The Origins of the Field of Masculinity and Suicide

The first decade of the literature (1954–1964) contained three articles. These publications were published in 1954 (Edelheit, Citation1954), 1958 (Rubenstein, Moses, & Lidz, Citation1958), and 1960 (Stone, Citation1960), and all three were published in the United States. Edelheit (Citation1954) and Rubenstein et al. (Citation1958) considered masculinity and suicidality in the context of severe mental illness and focused on masculinity being a risk factor in male suicidality, while Stone (Citation1960) focused on characteristics of masculinity such as suicidality in males being “an impulsive grasping for the active, aggressive masculine role” (p. 29).

Objective 2: The Evolution of the Field of Masculinity and Suicide

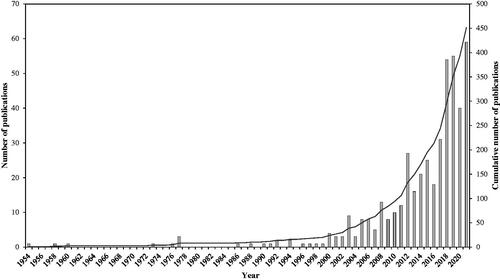

Between 1954 and 2021, 452 articles relating to masculinity and suicide were published. shows the distribution of publications by year. Between 1954 and 2007, the number of publications per year was fewer than 10. Even though the publication numbers increased to 13 in 2008, the research activity was still low from 2008 to 2011 (fewer than 15 publications per year). In 2012, there was a peak in the number of publications (n = 27), with publications in the years between 2012 and 2017 ranging from 16 to 27. In 2018, there was a major increase in the number of publications (n = 54), with publications in the years between 2018 and 2021 ranging from 40 to 59. The highest number of publications over the period was in 2021 (as at 05 November 2021); the upward trajectory appears to be continuing.

Objective 3a: Major Topics Discussed in the Literature

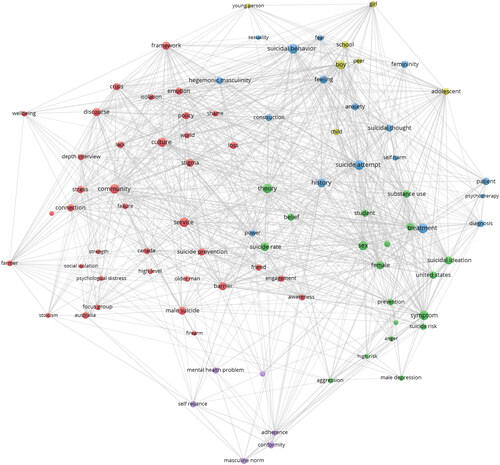

The most prominent terms in the masculinity and suicide literature are shown in . The terms were clustered by mapping the co-occurrences of terms from titles/abstracts of publications related to masculinity and suicide in the retrieved literature (1954–2021), as at 05 November 2021. Of the 9,184 terms, 143 occurred in at least 10 publications. For each of the 143 terms, a relevance score was calculated and used to select 60% of the most relevant terms. The largest set of linked terms included 86 terms and is shown in in five color-coded clusters.

FIGURE 3. Network visualization map of the co-occurrences of terms in title/abstract for publications related to masculinity and suicide (1954–2021). Colors indicate five clusters of related terms, and size of circles represents the occurrences of terms in titles/abstracts.

The red cluster was related to social and cultural elements of masculinity, with terms including social isolation, connection, well-being, stigma, loss, failure, Canada, and Australia. An example of this cluster is a publication (Alston, Citation2012) that discusses rural male suicide in Australia, and how rural masculinities are constructed in the Australian culture that restrict men’s ability to ask for help. The purple cluster was related to the self-reliance component of conformity to masculine norms in suicidality, with terms including conformity, masculine norm, mental health problem, and self-reliance. An example of this cluster is a publication (McDermott et al., Citation2018) that explores the relationship between intentions to seek psychological help for suicidal thoughts and conformity to masculine role norms in university students. The green cluster was related to risk factors in men’s suicidality, with terms including aggression, anger, male depression, substance use, and suicide risk. An example of this cluster is a publication (Rice et al., Citation2021) that investigates specific factors often associated with suicide risk in young men—depression symptoms, sexual abuse, and alcohol abuse. The blue cluster was related to mental health treatment, with terms including anxiety, diagnosis, fear, feeling, self-harm, psychotherapy, history, treatment, and patient. An example of this cluster is a publication (Dognin & Chen, Citation2018) that discusses the interplay of depression, suicidal behavior, and masculinities in veterans and highlights the role of dynamic interpersonal therapy in helping these men reconstruct their sense of self built in the “military culture”. Finally, the yellow cluster was related to suicidality in youth, with terms including adolescent, boy, child, girl, peer, school, and young person. An example of this cluster is a publication (King et al., Citation2020) that investigates the relationship between masculinity and suicidal ideation in adolescents.

Objective 3b: The Evolution of Topics Discussed in the Literature over Time

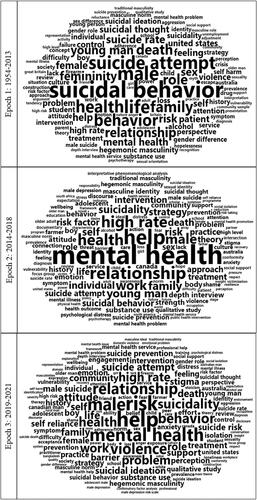

Epoch 1 (1954–2013) and epoch 2 (2014–2018) had 149 publications each, while epoch 3 (2019–2021) had 154 publications. The number of terms found by VOSviewer from epochs 1 to 3 were 3,186 terms, 3,569 terms, and 4,044 terms, respectively. The process of illustrating key terms according to publication occurrence helps to identify emerging topics. shows word clouds for the most commonly occurring terms found in titles/abstracts of the masculinity and suicide literature for each epoch. We omitted from the word clouds six single noun terms: masculinity, suicide, man, gender, woman, and depression, as they were the most occurring terms across all epochs and thus did not help to visualize/understand the evolution of topics discussed in the field. We included, however, compound noun terms related to the terms above (e.g., suicidal behavior, hegemonic masculinity, suicide prevention, male depression) as they were not in the top list of most occurring terms for all epochs. For a comprehensive list of the most occurring terms by epoch, including omitted terms, see Supplementary Table S2.

FIGURE 4. Word clouds of the most occurring terms in titles/abstracts for publications related to masculinity and suicide by epoch. Size of font represents the occurrences of terms in titles/abstracts

According to , prominent terms in epoch 1 (1954–2013) included sex, suicide attempt, and suicidal behavior, which can be broadly interpreted as related to sex differences in suicidality. An example of epoch 1 is a publication (Linehan, Citation1973) that investigates suicidal behavior as a function of sex in university students, showing evidence for suicide death being considered more masculine than attempted suicide. Prominent terms in epoch 2 (2014–2018) included mental health, relationship, and work, which can be broadly interpreted as related to men’s relationship to work and its impact on their mental health and suicidality. An example of epoch 2 is a publication (Oliffe & Han, Citation2014) that discusses masculinities and men’s health, men and work, men’s work-related depression and suicide, and men’s mental health promotion. Prominent terms in epoch 3 (2019–2021) included help, self-reliance, and barrier, which can be broadly interpreted as characteristics of help-seeking in suicidality. An example of epoch 3 is a publication (Ross, Caton, Gullestrup, & Kolves, Citation2019) that investigates the effectiveness of a suicide prevention intervention designed to encourage help-seeking and help-offering in men working in construction.

Objective 4: The Most Influential Publications in Masculinity and Suicide

The WoS search returned 327 publications with citation data as at 18 December 2021. However, as the earliest publication in this database was from 1991, we only included publications from epochs 2 and 3 (i.e., 2014–2021, n = 251) in this analysis.

The publication with the highest citation count per year and total citation count (average of 15.6 citations per year, 78 citations in total) was by Pirkis et al. (Citation2017). This publication describes an Australian cohort study (n = 13,884 adult men) investigating the relationship between conformity to dominant masculine norms and suicidal ideation. Pirkis and colleagues found that self-reliance, a dimension of dominant masculine norms, is a key risk factor for suicidal ideation in men. The publication with the second highest citation count per year was by Rice, Purcell, and McGorry (Citation2018). This publication is a narrative review by Australian researchers about the mental health of adolescent boys and young men. Synthetized key themes within the review include “cultural expectations and masculinity”. The authors highlight the issue in Western society whereby boys and men are discouraged to demonstrate vulnerability, weakness, or emotions. They also discussed the modeling of help-seeking behaviors for men, arguing that they are modeled from a very young age within the family of origin and community context. The publication with the third highest citation per year was by McKenzie, Collings, Jenkin, and River (Citation2018). This publication describes a qualitative study conducted in New Zealand that explored the interplay between masculinity, men’s everyday social practices, and mental health. This study found four major patterns in men’s social relationships: (1) compartmentalizing relationships (i.e., differentiating between relationships with men and women); (2) difficulties in confiding and mobilizing support in times of difficulty/distress; (3) desire to be independent; and (4) endeavor to create support networks to actively seek support. For the ten most influential masculinity and suicide publications in WoS, see Supplementary Table S3.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to report the origins and evolution of research at the confluence of masculinity and suicide. In providing an overview of publication trends and by examining changes in topic foci over time we provide new knowledge on the scope, structure, and maturity of the field.

We identified that the masculinity and suicide field originated in the 1950s. However, it was not until recently that the field grew to any degree. This trend is in line with previous bibliometric studies conducted in the field of suicide (Astraud et al., Citation2020; Cai et al., Citation2020), where a steady growth was observed from around 2004 onwards; see Figure 1 in Astraud et al. (Citation2020) and Figure 2 in Cai et al. (Citation2020). Furthermore, our bibliometric study found that the earliest publications discussed masculinity and suicide in the context of severe mental illness, suggesting the use of a medical model of suicide by which suicide is mainly an outcome of mental disorders (Isacsson, Citation2000; Miles, Citation1977). Although the use of a medical model was consistent with dominant suicide theories of the time, it is possible that it viewed male suicide and masculinity simplistically, where suicide was an outcome of not fulfilling a role (Stone, Citation1960) or being mentally ill (Edelheit, Citation1954; Rubenstein et al., Citation1958). Leading thinkers in suicide prevention have now moved away from this medical model, viewing suicide as a more complex phenomenon that is influenced by a range of risk factors. Mental illness is only one of these; a range of societal and cultural factors also play a major role in male suicide, including gun policies (Wamser-Nanney, Citation2021), social isolation (Oliffe et al., Citation2019), help-seeking behavior (Ross et al., Citation2019), and aspects of masculinity (Pirkis et al., Citation2017).

This study also shows key emergent research areas within the masculinity and suicide literature, with research themes from biology, sociology, and psychology. Emergent research areas included mental health treatment as a means of suicide prevention; risk factors in men’s suicidality, including social and cultural elements of masculinity, particularly the traditional masculine norm of self-reliance; and suicide in young people. This broadened focus is consistent with more recent understandings of suicide as a complex phenomenon with many contributing factors.

We also identified noticeable changes in discussions regarding masculinity and suicide over time. The discussions shifted from focusing solely on individual-level risk factors (e.g., sex and mental illness) to incorporating broader social and cultural determinants (e.g., gender and help-seeking), suggesting that researchers have recently begun to unpack the mechanisms by which male suicide occurs, and the extent to which this is influenced by conformity to masculine norms. This evolving knowledge has given rise to a growing number of suicide prevention campaigns targeting traditional masculinity and help-seeking behavior in men (King, Schlichthorst, Spittal, Phelps, & Pirkis, Citation2018; King et al., Citation2019; Ross et al., Citation2019).

Strengths and Limitations

This study has several strengths. Firstly, it is the first study to explore the trends and content in the masculinity and suicide field using bibliometric methods. Secondly, we searched eight electronic databases from a wide range of fields, thereby capturing the most relevant literature as comprehensively as possible. A limitation of this study was that the search for the citation count analysis relied on a single source (i.e., WoS), meaning that our list of the most influential publications may not represent the whole literature. However, this source is one of the most comprehensive indices of peer-reviewed multidisciplinary literature available, including citation data.

CONCLUSIONS

This study offers new knowledge in the field of masculinity and suicide. The field of masculinity and suicide has grown considerably in the last few years; however, its structure, content and direction are still evolving. Researchers must work with policy makers and practitioners to ensure further work is conducted to design and evaluate appropriate interventions, and that emerging findings are translated for use in programs designed to address suicide in boys and men.

ETHICS APPROVAL

Not applicable as the data used in this study are publicly available.

CREDIT AUTHOR STATEMENT

Simone Scotti Requena: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – Original Draft; Jane Pirkis: Writing – Review & Editing, Supervision; Dianne Currier: Writing – Review & Editing; Angela Nicholas: Writing – Review & Editing; Adriano A. Arantes: Software, Visualization; Nigel R. Armfield: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – Review & Editing, Supervision. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (92.4 KB)ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Lindy Cochrane (research librarian at the University of Melbourne) for her assistance with the search strategy development.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Simone Scotti Requena

Simone Scotti Requena, Jane Pirkis, Dianne Currier, and Angela Nicholas, Centre for Mental Health, Melbourne School of Population and Global Health, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia.

Jane Pirkis

Simone Scotti Requena, Jane Pirkis, Dianne Currier, and Angela Nicholas, Centre for Mental Health, Melbourne School of Population and Global Health, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia.

Dianne Currier

Simone Scotti Requena, Jane Pirkis, Dianne Currier, and Angela Nicholas, Centre for Mental Health, Melbourne School of Population and Global Health, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia.

Angela Nicholas

Simone Scotti Requena, Jane Pirkis, Dianne Currier, and Angela Nicholas, Centre for Mental Health, Melbourne School of Population and Global Health, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia.

Adriano A. Arantes

Adriano A. Arantes, Independent Researcher, Brisbane, Australia, and

Nigel R. Armfield

Nigel R. Armfield, RECOVER Injury Research Centre, Faculty of Health and Behavioural Sciences, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia, Centre for Health Services Research, Faculty of Medicine, Brisbane, The University of Queensland, Australia.

REFERENCES

- Alston, M. (2012). Rural male suicide in Australia. Social Science & Medicine, 74(4), 515–522. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.04.036

- Armfield, N. R., Edirippulige, S., Caffery, L. J., Bradford, N. K., Grey, J. W., & Smith, A. C. (2014). Telemedicine – A bibliometric and content analysis of 17,932 publication records. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 83(10), 715–725. doi:10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2014.07.001

- Astraud, L.-P., Bridge, J. A., & Jollant, F. (2020). Thirty years of publications in suicidology: A bibliometric analysis. Archives of Suicide Research, 25(4), 751–764.

- Briganti, M., Delnevo, C. D., Brown, L., Hastings, S. E., & Steinberg, M. B. (2019). Bibliometric analysis of electronic cigarette publications: 2003–2018. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(3), 320. doi:10.3390/ijerph16030320

- Broadus, R. N. (1987). Toward a definition of “bibliometrics”. Scientometrics, 12(5–6), 373–379. doi:10.1007/BF02016680

- Cai, Z., Chang, Q., & Yip, P. S. (2020). A scientometric analysis of suicide research: 1990–2018. Journal of Affective Disorders, 266, 356–365. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2020.01.121

- Chen, S., Lu, Q., Bai, J., Deng, C., Wang, Y., & Zhao, Y. (2020). Global publications on stigma between 1998 and 2018: A bibliometric analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 274, 363–371.

- Cleary, A. (2012). Suicidal action, emotional expression, and the performance of masculinities. Social Science & Medicine, 74(4), 498–505. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.08.002

- Cleary, A. (2019). The gendered landscape of suicide: Masculinities, emotions, and culture. Berlin: Springer.

- Connell, R. W., & Messerschmidt, J. W. (2005). Hegemonic masculinity: Rethinking the concept. Gender & Society, 19(6), 829–859.

- Dognin, J. S., & Chen, C. K. (2018). The secret sorrows of men: Impact of dynamic interpersonal therapy on ‘masculine depression’. Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy, 32(2), 181–196. doi:10.1080/02668734.2018.1458747

- Eck, N. J. v., & Waltman, L. (2009). VOSviewer. In (Version 1.6.17). Leiden: Leiden University.

- Edelheit, H. (1954). Mixed psychoneurosis with character defect and later symptomatic changes. Journal of the Hillside Hospital, 3(1), 40–59. http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emcl1&NEWS=N&AN=280830281

- Isacsson, G. (2000). Suicide prevention – A medical breakthrough? Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 102(2), 113–117. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.102002113.x

- King, K., Schlichthorst, M., Turnure, J., Phelps, A., Spittal, M. J., & Pirkis, J. (2019). Evaluating the effectiveness of a website about masculinity and suicide to prompt help‐seeking. Health Promotion Journal of Australia, 30(3), 381–389. doi:10.1002/hpja.237

- King, K. E., Schlichthorst, M., Spittal, M. J., Phelps, A., & Pirkis, J. (2018). Can a documentary increase help-seeking intentions in men? A randomised controlled trial. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 72(1), 92–98. doi:10.1136/jech-2017-209502

- King, T. L., Shields, M., Sojo, V., Daraganova, G., Currier, D., O’Neil, A., … Milner, A. (2020). Expressions of masculinity and associations with suicidal ideation among young males. BMC Psychiatry, 20(1), 1–10. doi:10.1186/s12888-020-2475-y

- Levant, R. F., & Pryor, S. (2020). The tough standard: The hard truths about masculinity and violence. USA: Oxford University Press.

- Linehan, M. M. (1973). Suicide and attempted suicide: Study of perceived sex differences. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 37(1), 31–34. doi:10.2466/pms.1973.37.1.31

- Mahalik, J. R., Locke, B. D., Ludlow, L. H., Diemer, M. A., Scott, R. P., Gottfried, M., & Freitas, G. (2003). Development of the conformity to masculine norms inventory. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 4(1), 3–25. doi:10.1037/1524-9220.4.1.3

- McDermott, R. C., Smith, P. N., Borgogna, N., Booth, N., Granato, S., & Sevig, T. D. (2018). College students’ conformity to masculine role norms and help-seeking intentions for suicidal thoughts. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 19(3), 340–351. doi:10.1037/men0000107

- McKenzie, S. K., Collings, S., Jenkin, G., & River, J. (2018). Masculinity, social connectedness, and mental health: Men’s diverse patterns of practice. American Journal of Men’s Health, 12(5), 1247–1261.

- Mergl, R., Koburger, N., Heinrichs, K., Székely, A., Tóth, M. D., Coyne, J., … Maxwell, M. (2015). What are reasons for the large gender differences in the lethality of suicidal acts? An epidemiological analysis in four European countries. PLoS One, 10(7), e0129062. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0129062

- Miles, C. P. (1977). Conditions predisposing to suicide: A review. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 164(4), 231–246.

- Möller-Leimkühler, A. M. (2002). Barriers to help-seeking by men: A review of sociocultural and clinical literature with particular reference to depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 71(1–3), 1–9. doi:10.1016/S0165-0327(01)00379-2

- Oliffe, J. L., Broom, A., Popa, M., Jenkins, E. K., Rice, S. M., Ferlatte, O., & Rossnagel, E. (2019). Unpacking social isolation in men’s suicidality. Qualitative Health Research, 29(3), 315–327. doi:10.1177/1049732318800003

- Oliffe, J. L., & Han, C. S. (2014). Beyond workers’ compensation: Men’s mental health in and out of work. American Journal of Men’s Health, 8(1), 45–53.

- Pai, R. R., & Alathur, S. (2020). Bibliometric analysis and methodological review of mobile health services and applications in India. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 145, 104330.

- Pirkis, J., Spittal, M. J., Keogh, L., Mousaferiadis, T., & Currier, D. (2017). Masculinity and suicidal thinking. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 52(3), 319–327. doi:10.1007/s00127-016-1324-2

- Pompili, M., Serafini, G., Innamorati, M., Dominici, G., Ferracuti, S., Kotzalidis, G. D., … Tatarelli, R. (2010). Suicidal behavior and alcohol abuse. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 7(4), 1392–1431. doi:10.3390/ijerph7041392

- Pranckutė, R. (2021). Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus: The Titans of bibliographic information in today’s academic world. Publications, 9(1), 12. doi:10.3390/publications9010012

- R Core Team. (2021). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. In (Version 4.1.2) https://www.R-project.org/.

- Rice, S. M., Kealy, D., Seidler, Z. E., Walton, C. C., Oliffe, J. L., & Ogrodniczuk, J. S. (2021). Male-type depression symptoms in young men with a history of childhood sexual abuse and current hazardous alcohol use. Psychiatry Research, 304, 114110. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114110

- Rice, S. M., Purcell, R., & McGorry, P. D. (2018). Adolescent and young adult male mental health: Transforming system failures into proactive models of engagement. Journal of Adolescent Health, 62(3), S9–S17. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.07.024

- Ross, V., Caton, N., Gullestrup, J., & Kolves, K. (2019). Understanding the barriers and pathways to male help-seeking and help-offering: A mixed methods study of the impact of the mates in construction program. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(16), 2979–2912. doi:10.3390/ijerph16162979

- Rubenstein, R., Moses, R., & Lidz, T. (1958). On attempted suicide. A.M.A. archives of Neurology and Psychiatry, 79(1), 103–112. http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emcl1&NEWS=N&AN=280957524

- San Too, L., Spittal, M. J., Bugeja, L., Reifels, L., Butterworth, P., & Pirkis, J. (2019). The association between mental disorders and suicide: A systematic review and meta-analysis of record linkage studies. Journal of Affective Disorders, 259, 302–313.

- Schneider, B. (2009). Substance use disorders and risk for completed suicide. Archives of Suicide Research, 13(4), 303–316. doi:10.1080/13811110903263191

- Stone, A. A. (1960). A syndrome of serious suicidal intent. Archives of General Psychiatry, 3(4), 331–339. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1960.01710040001001

- The EndNote Team. (2013). EndNote. In (Version 20) [64 bit]. London: Clarivate.

- Van Eck, N. J., & Waltman, L. (2010). Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics, 84(2), 523–538. doi:10.1007/s11192-009-0146-3

- Van Eck, N. J., & Waltman, L. (2011). Text mining and visualization using VOSviewer. arXiv, preprint arXiv:1109.2058

- Van Eck, N. J., & Waltman, L. (2013). VOSviewer manual. Leiden: Univeristeit Leiden, 1(1), 1–53.

- Wamser-Nanney, R. (2021). Understanding gun violence: Factors associated with beliefs regarding guns, gun policies, and gun violence. Psychology of Violence, 11(4), 349–353. doi:10.1037/vio0000392

- Wong, Y. J., Ho, M.-H R., Wang, S.-Y., & Miller, I. (2017). Meta-analyses of the relationship between conformity to masculine norms and mental health-related outcomes. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 64(1), 80–93. doi:10.1037/cou0000176

- World Health Organization. (2021a). Suicide worldwide in 2019: Global health estimates. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240026643.

- World Health Organization. (2021b). Suicide: Key facts. Geneva: WHO.

- Xu, D., Wang, Y.-L., Wang, K.-T., Wang, Y., Dong, X.-R., Tang, J., & Cui, Y.-L. (2021). A scientometrics analysis and visualization of depressive disorder. Current Neuropharmacology, 19(6), 766–786. doi:10.2174/1570159X18666200905151333