Abstract

Objectives

Suicide prevention gatekeeper training (GKT) is considered an important component of an overall suicide-prevention strategy. The primary aim of this study was to conduct the first robust review of systematic reviews of GKT to examine the overall effectiveness of GKT on knowledge, self-efficacy, attitudes, behavioral intentions, and behavioral change. The study also examined the extent to which outcomes were retained long term, the frequency of refresher sessions, and the effectiveness of GKT with Indigenous populations and e-learning delivery.

Methods

For this review of reviews, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Embase; and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews were searched. ROBIS was applied to assess risk of bias and findings were synthesized using narrative synthesis.

Results

Six systematic reviews were included comprising 61 studies, of which only 10 were randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Immediate positive effects of GKT on knowledge, skills, and self-efficacy were confirmed, including for interventions tailored for Indigenous communities. Evidence was mixed for change in attitude; few studies measured e-learning GKT, retention of outcomes, booster sessions, behavioral intentions, and behavioral change, with some positive results.

Conclusions

Evidence supports the immediate effects of GKT but highlights a need for more high-quality RCTs, particularly for Indigenous and e-learning GKT. This review identified a concerning lack of long-term follow-up assessments at multiple time points, which could capture behavioral change and a significant gap in studies focused on post-training interventions that maintain GKT effects over time.

HIGHLIGHTS

This first review of systematic reviews for GKT confirmed positive effects for GKT, although mixed evidence exists for changes in attitude.

Very few studies include long-term measurement of retention of outcomes and what facilitates retention.

There is an urgent need for more research into the effectiveness of GKT with Indigenous populations and e-learning GKT.

INTRODUCTION

Suicide is a significant global public health issue. Annually, approximately 800,000 people worldwide take their own life, and significantly more attempt suicide (World Health Organization, Citation2018). The causes of suicide are multifaceted, and it is widely accepted that effective national responses to preventing suicide should take a comprehensive multilevel approach across sectors (World Health Organization, Citation2014).

Gatekeeper suicide prevention training (GKT) is integral to an overall national suicide prevention strategy according to the United Nations, the WHO, and numerous reviews of suicide-prevention strategies (Beautrais et al., Citation2007; Mann et al., Citation2005; van der Feltz-Cornelis et al., Citation2011). The term gatekeeper refers to community members who are likely to have regular contact with people at risk of suicide and can open the “gate” to support services. GKT recognizes that individuals are unlikely to seek help independently and often require support (Kuhlman et al., Citation2017; Pisani et al., Citation2012). A pivotal theory in GKT is the theory of planned behavior (TPB; Ajzen, Citation1991), which posits that knowledge, self-efficacy, and attitudes explain behavioral intentions, which predict the likelihood that behavioral change will occur. Therefore, the central focus of GKT is to improve trainee knowledge, skills, and attitudes to improve intentions to intervene with someone at risk of suicide (Kuhlman et al., Citation2017).

Gatekeeper training varies widely in duration and content as well as training modality (in-person or web-based, predominantly e-learning programs). The roles of gatekeepers may differ in terms of their intervention techniques and strategies. The most widely available GKTs are Applied Suicide Intervention Skills Training (ASIST) and Question Persuade and Respond (QPR). Both have distinct approaches, with ASIST focusing on providing skills to intervene, assess risk, and support someone in crisis by developing a safety plan, while QPR centers around questioning individuals about suicide, persuading them to seek help, and referring them to appropriate resources.

While some evidence for positive impacts of GKT on knowledge, attitude, and self-efficacy immediately post-training exists, the retention of positive gains over time is less clear (Stone & Crosby, Citation2014). Further, there are mixed results regarding post-training boosters or refresher sessions on retention of knowledge, attitude, and self-efficacy (Johnson & Parsons, Citation2012). Wyman et al. (Citation2008) indicated booster training had no effect on outcomes, while Shtivelband et al. (Citation2015) suggested booster sessions comprising ongoing connections with trainees, further education, reminders, and certification are likely to be more effective.

Concerns also exist regarding the evidence for GKT’s effectiveness with Indigenous communities (Nasir et al., Citation2016). Worldwide, Indigenous populations experience higher rates of suicide compared to the general population (Pollock et al., Citation2018). Mainstream approaches may not suit these, often colonized, populations if they do not adequately address the cultural nuances, values, and beliefs of Indigenous populations or the impact of colonization and historical trauma (Sjoblom et al., Citation2022). Additionally, the distinct social structures of Indigenous communities, their strong connections to spirituality and land and a collective emphasis on well-being. is often overlooked in mainstream approaches. However, when GKT is cocreated and tailored to the context of the specific Indigenous communities, there is emerging evidence to suggest that GKT can be effective in changing attitudes and increasing knowledge and self-efficacy (Clifford et al., Citation2013; Nasir et al., Citation2016).

There are other important gaps in the current evidence base. For example, there is limited understanding of whether the gains for knowledge, attitude, and self-efficacy result in trainees effectively engaging with someone at risk of suicide or making necessary referrals for support. Some studies have reported increases in such behaviors following GKT (Bartgis & Albright, Citation2016; Zinzow et al., Citation2020), while others have found no change (Sareen et al., Citation2013; Wyman et al., Citation2008).

Finally, there is limited understanding regarding the impact of the modality of delivery of GKT, in particular self-directed e-learning modalities, which have increased in response to limited access to in-person training, particularly during the COVID pandemic. The effects of e-learning modalities are unclear, but initial studies show promise (Ghoncheh et al., Citation2016).

To our knowledge, there has not been a review of systematic reviews for GKT conducted to date. The primary aim of this study was to examine the overall effectiveness of suicide prevention GKT on knowledge, self-efficacy, attitudes, behavioral intentions, and behavioral change at the review level through a robust review of systematic reviews.

The secondary aims were to examine:

GKT effectiveness with Indigenous populations at the review level;

the extent of follow-up and retention of outcomes over time across individual studies; and effectiveness at review level;

the extent to which e-learning delivery was used across individual studies; and

frequency of booster or refresher sessions across individual studies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The authors adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement (PRISMA) (Moher et al., Citation2009) and Cochrane guidelines for the reviews of reviews (Higgins & Green, Citation2011).

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria were:

peer-reviewed systematic reviews, including studies of GKT interventions defined as education about risk factors, warning signs, engaging someone who exhibits warning signs, and referral processes;

suicide prevention GKT delivered to the general public not medical and health professionals, and via any modality, i.e., face-to-face, or online;

experimental design, including pre/post studies and controlled trials; and

any age group.

Cochrane systematic reviews, non-Cochrane systematic reviews, and meta-analyses were included if they included:

a systematic search of at least three databases;

description of the approach for inclusion and exclusion; and

systematic description of all included studies.

The exclusion criteria were:

systematic reviews that only included studies of interventions where GKT was included as a part of a multifaceted intervention;

systematic reviews that included nonexperimental studies.

Search Strategy

A systematic search was conducted from February 2000 to February 2024. The electronic research databases searched included: OVID, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Embase, and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.

The following terms and combinations were searched: “gatekeeper*,” “gate-keeper*,” “suicide/,” “suicidal ideation/,” “suicide, attempted/,” “suicid*,” “meta-analysis/,” “systematic review,” “network meta-analysis/,” “met-analy*,” “metanaly*,” “meta-analy*,” “metaanaly*,” “systematic*,” “review*,” “overview*,” and “methodologic*.”

The search strategy combined subject headings (e.g., MESH in Medline) with free-text terms. Searches were designed with an experienced information specialist and run by DKU and RT. The search was limited to articles in academic journals.

Selection Process

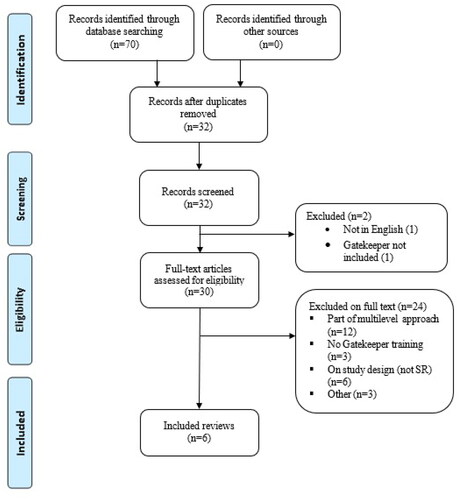

One author (DKU) screened titles and abstracts. From this selection, DKU and SH evaluated the full texts independently (). Disagreements about inclusion were resolved by discussion and peer-moderation.

FIGURE 1. PRISMA (Moher et al., Citation2009) diagram of review identification, screening, and selection.

Data Extraction and Data Management

Three authors (DKU, RT, NT) conducted the data extraction with disagreements resolved by consensus.

At the review level, the authors extracted:

publication details ();

inclusion and exclusion criteria ();

population details ();

number of included studies (Supplementary Material Table 1); and

findings ().

TABLE 1. Participant, study design, criteria, and outcome of systematic reviews.

Risk of Bias Assessment

Risk of bias assessments for each review were conducted using the Risk of Bias in Systematic reviews (ROBIS) tool (Whiting et al., Citation2016) by NT and DKU. ROBIS is distinct from the AMSTAR tool, which assesses study quality more broadly (Banzi et al., Citation2018; Shea et al., Citation2017).

Synthesis

First, we described the characteristics, risk of bias, and findings for our main outcomes at the review level using narrative synthesis. Second, we described details of individual studies for other outcomes of interest.

RESULTS

Identified Reviews

The searches retrieved 70 records; 38 duplicates were removed. The remaining 32 articles were screened using titles and abstract, with two records excluded. Thirty articles were retrieved for full-text assessment. A total of six systematic reviews were included (see PRISMA flowchart, ).

Description of Included Systematic Reviews

The six systematic reviews are summarized in . They comprise 86 studies; 25 were included in more than one review, giving a total of 61 unique studies (see Supplementary Material, ).

Characteristics of Systematic Reviews Studies

Two reviews focused on school settings (Mo et al., Citation2018; Torok et al., Citation2019). Holmes et al. (Citation2021) focused on school settings and community members. Isaac et al. (Citation2009) and Yonemoto et al. (Citation2019) included mixed settings.

Nasir et al. (Citation2016) only included studies with Indigenous populations (five studies in total). The target audience included Australian Indigenous youth, Australian Indigenous youth and community members, Native American college students, Zuni Native American youth, and a group of Canadian First Nation youth, under the age of 16 years.

Risk of Bias Assessment of Included Systematic Reviews

As shown in , the six systematic reviews varied in terms of risk of bias. Two were judged to be at low risk of bias (Mo et al., Citation2018; Yonemoto et al., Citation2019), one unclear (Torok et al., Citation2019) and three at high risk of bias (Holmes et al., Citation2021; Isaac et al., Citation2009; Nasir et al., Citation2016). See Supplementary Material, for full ROBIS assessment.

TABLE 2. Tabular presentation for ROBIS results.

Four reviews applied an appropriate study eligibility criterion for the review questions. The eligibility criteria (inclusion and exclusion) were aligned to review questions. However, Nasir et al. (Citation2016) and Isaac et al. (Citation2009) did not clearly state study designs as eligibility criteria (these were described in results).

For the identification and selection of studies, four reviews were judged to be at low risk of bias. All reviews used an appropriate range of databases. The main databases searched were Ovid, Medline, Embase, Psych INFO, ERIC, Scopus, PubMed, CINAHL, The Cochrane Database of Systematic reviews. Only one review utilized grey literature (Nasir et al., Citation2016). Four reviews used two reviewers to independently screen the inclusion of studies based on the abstracts and full text. Holmes et al. (Citation2021) and Yonemoto et al. (Citation2019) did not explicitly describe their selection process.

In terms of data collection and study appraisal, two studies, Mo et al. (Citation2018) and Yonemoto et al. (Citation2019), reported efforts to minimize error during data extraction, including at least two reviewers independently undertaking this process and a structured data extraction form. All systematic reviews applied narrative synthesis due to the heterogeneity of study design, outcome measures, participants, and characteristics that precluded meta-analysis.

Four reviews did not formally assess risk of bias or methodological quality of included studies. The two studies that did (Mo et al., Citation2018; Yonemoto et al., Citation2019) found that the studies were generally of low methodological quality.

Characteristics of Individual Studies Included in the Systematic Reviews

See Supplementary Material, Table 3 for full description of studies.

Type of Study Design

The studies across all the reviews comprised a range of study designs, with the majority being quasi-experimental studies. Only 10 of the 61 studies were randomized controlled trials (RCTs) ().

Type of GKT Programs

The main GKT interventions across studies consisted of: QPR; n = 16 and ASIST; n = 3. The remainder were community tailored programs.

Indigenous Populations

Of the 61 individual studies, 12 (19.7%) examined GKT’s conducted in non-Western communities. Of these 12 studies, eight were conducted in Indigenous populations (Australian Aboriginal communities (n = 2), Canadian First-Nations communities (n = 1), and American Indigenous communities (n = 5). Of these eight studies, in six the GKT was adapted for the Indigenous communities; in the RCT the intervention was not tailored (Sareen et al., Citation2013), and in the online study the adaptation was limited to including multiethnic avatars (Bartgis & Albright, Citation2016). No New Zealand Indigenous Māori studies were identified.

E-Learning GKT

Four individual studies, which were included in Holmes et al. (Citation2021) and Torok et al. (Citation2019), investigated an e-learning GKT modality, each of a different GKT program (QPR, Mental Health Online, Making Educators Partners, and Kognito Gatekeeper Simulations).

Key Outcomes Described at a Review Level Across the Six Systematic Reviews

Knowledge and Skills

Every review described self-report knowledge and skills as an outcome and aimed to extract data on this. Holmes et al. (Citation2021) highlighted that knowledge was the most commonly reported GKT outcome, reported in 79% (n = 19) of studies, and this was consistent across the other five reviews ( shows 54% to 93% reported knowledge and skills). In all but five studies across the included reviews, there was evidence of improvements in these outcomes. Increased knowledge and skills with Indigenous populations was reported by Nasir et al. (Citation2016).

Four reviews reported that the positive effects were retained at long-term follow-up. Two reviews found these outcomes were retained 6 to 12 months post-training (Isaac et al., Citation2009; Yonemoto et al., Citation2019). Mo et al. (Citation2018) found mixed outcomes. Holmes et al. (Citation2021) reported a decay over time in 12 of 15 studies but highlighted that those outcomes remained higher than pre-training results.

Self-Efficacy

All reviews concluded that GKT significantly increased gatekeepers’ self-efficacy. Self-efficacy was reported in between 23% and 85% of studies and, in every case, findings were positive. Nasir et al. (Citation2016) reported that within Indigenous populations there was an increase in self-efficacy, as reported in the three studies evaluating this outcome. Several reviews suggested self-efficacy is the most enduring outcome with gains remaining at 6 to 9 months follow-up (Holmes et al., Citation2021; Mo et al., Citation2018; Nasir et al., Citation2016).

Attitude

Five reviews evaluated changes in participants’ attitudes about suicide post-training. Attitude change was reported in between 0% and 62% of studies. In three reviews, the studies reported mixed results, with the authors suggesting ceiling effects and voluntary attendance may impact results (Holmes et al., Citation2021; Mo et al., Citation2018; Torok et al., Citation2019). One review reported improvements in three (of 13) studies that reported on attitude, but they were perceived as low-quality individual cohort studies (Isaac et al., Citation2009). Yonemoto et al. (Citation2019) found no change in the one (of 16) RCT study regarding attitude which compared QPR with a no-training comparator.

Four reviews reported on follow-up measurement of attitude but, due to the small number of studies and unclear outcomes, it is difficult to conclude if any attitude improvements were maintained over time.

Behavioral Intentions

Four reviews captured the behavioral intention to intervene with someone at risk of suicide as an outcome, with all reporting that intention increased. Mo et al. (Citation2018) reported improvements in two (of 14) studies; Yonemoto et al. (Citation2019) reported increases in six studies (of 16); Holmes et al. (Citation2021) in 10 studies, but no change in one study (of the 11 studies reporting on intentions out of 24). Nasir et al. (Citation2016) found two out of three studies that measured intentions (out of five included studies) showed increases. All studies involved workshops targeting Indigenous Australian youth and were developed in consultation with the Aboriginal community. One was a two-year follow-up of one of the three studies. Initially, no changes in intentions were noted as the baseline scores were already high. However, the two-year follow-up reported increases and a relationship between pre-intentions and actually helping someone who was suicidal (Deane et al., Citation2006).

Behavior Change

While most systematic reviews in this study reported on some form of behavior change, outcomes were based on only a few individual studies within each review. Gatekeeper behavior change was not a focus in the Isaac et al. (Citation2009) review, therefore not reported.

Four reviews reported on intervening or referring behavior (see ). In the Nasir et al. (Citation2016) review, only two out of the five studies report on intervening behavior and one on referring behavior. For the other reviews: three out of 14 (Mo et al., Citation2018), four out of 13 (Torok et al., Citation2019), 11 out of 24 (Holmes et al., Citation2021), and eight out of 16 (Yonemoto et al., Citation2019) reported both behavioral outcomes.

Overall, there were mixed results (noting this outcome was only measured in between 21% and 50% of studies). There was some nuance in these mixed results; for example, Torok et al. (Citation2019) reported no improvements in identification and referrals by teachers but that referrals increased among school counselors. Holmes et al. (Citation2021) found moderate support for an increase in referrals (eight out of 11 studies) but weaker support for intervention (six of 11 studies).

Nasir et al. (Citation2016) found mixed results in the two studies (of five) of Indigenous populations reporting on these outcomes. One study showed 37.5% of gatekeepers reported supporting someone at risk of suicide at the two-year follow-up, with a significant relationship between intentions to intervene and helping someone at risk of suicide (Deane et al., Citation2006). In the only RCT, there was no difference in behaviors between GKT and the control training group. The authors suggest this may be due to a small sample size and because the participants differed from most GKT studies, as they were youth with a history of suicidal behaviors.

Overall, 65% of studies reported follow-up assessment of behavioral change. However, most were within 3 to 6 months, and such short-term follow-up may not give people the opportunity to encounter someone at risk; therefore, it is difficult to demonstrate behavioral change. In the reviews that reported long-term follow-up, Mo et al. (Citation2018) and Nasir et al. (Citation2016), there was clear evidence of behavioral change at one-year and two-year follow-up.

E-Learning Modalities

Improvements in knowledge, self-efficacy, and attitude were reported in all four studies and improvements in behavioral change were noted in the three studies that reported this outcome. Results from an RCT of e-learning GKT showed increases in knowledge and self-efficacy after GKT was delivered via eight sessions (5 to 10-minute duration), with improvements retained at three-month follow-up (Ghoncheh et al., Citation2016).

Follow-Up Assessment

More than half of the 61 individual studies analyzed (n = 40; 65.6%) included a follow-up assessment of outcomes. The timing of follow-up assessment varied significantly; 19 (of 40) studies carried out a follow-up at 1–3 months after the post training assessment, 17 at 4–6 months, seven at 7–12 months, and six at 1–2 years. Only five of the 40 studies included more than one follow-up assessment; three of these five included two post-training assessment time points, 1 and 3 months, and 3 and 12 months; one study had five follow-ups (bi-monthly for 12 months) and one study had three follows-ups (monthly for three months).

Booster or Refresher Sessions

Few studies (5 out of 61, 8.2%) included booster or refresher sessions, and these varied enormously. Parents of youth in an at-risk youth program in the United States received a phone call 2.5 months post-training to reinforce skills in one study (Hooven, Citation2013); general practitioners (GPs) in Sweden were offered access to a 1-day seminar (Henriksson & Isacsson, Citation2006); GPs and nurses in Hungary were offered attendance for three 1-hour lectures annually for four years (Szanto et al., Citation2007); school staff in the United States were invited to a 30-minute QPR refresher several months after training (Wyman et al., Citation2008); and Australian Indigenous service providers and community members had access to a follow-up forum 6–12 months following GKT (Westerman, Citation2007).

Only two of these five studies reported on outcomes for refresher sessions. Wyman et al. (Citation2008) found no effect on training outcomes. Westerman (Citation2007) found that “follow-up forums” had a medium to large effect on training outcomes.

DISCUSSION

This review of six systematic reviews included a range of GKT programs comprising 61 individual studies conducted in a variety of settings. The risk of bias in four of the six reviews was judged as high or unclear, and only 10 of the 61 included studies were RCTs.

Overall, results showed that knowledge and skills was impacted positively, as well as increases in intentions to intervene with someone at risk of suicide, with self-efficacy showing the most robust change. These results are important given that the theory of planned behavior proposes perceived knowledge, self-efficacy, and attitudes explain behavioral intentions, which predict the likelihood that behavioral change will occur. While there were more inconsistent results regarding attitudes, research by Kuhlman et al. (Citation2017) found that perceived knowledge and self-efficacy appear to be the most significant predicters of behavioral change following GKT.

Several factors have been proposed to explain mixed outcomes regarding attitudes, such as whether a participant attends GKT voluntarily or is required to attend (Holmes et al., Citation2021). Ceiling effects, particularly for those who attend voluntarily, are a noted methodological problem (Mo et al., Citation2018). It has been suggested that altering a person’s attitude, especially within the constraints of a brief 2-hour training session (Coppens et al., Citation2014), poses challenges. Therefore, it has been proposed that a preliminary approach to shifting attitudes might involve enhancing participants’ awareness of the pivotal role attitudes play (Montiel & Mishara, Citation2023).

There were few studies reporting on intervening behaviors. Those that did reported mixed results, making it difficult to reach any firm conclusions about the GKT effectiveness for behavior change. Our review suggests this may be due to the length of follow-up for measurement of these outcomes, which was mostly over a short time frame. Capturing behavioral change is primarily dependent on a trainee encountering someone at risk of suicide post-training, so short-term follow-up does not provide sufficient opportunity to encounter someone at risk and use these skills to intervene, making it difficult to demonstrate behavioral change. Studies investigating the sustainability of results beyond 6 months reveal encouraging findings regarding trainees’ continued support for individuals at risk of suicide, with evidence persisting at the 12-month follow-up (Mo et al., Citation2018) and even after 2 years (Nasir et al., Citation2016).

The inequities in health outcomes for Indigenous populations are well recognized and reflected in high rates of suicide, particularly among Indigenous youth (Pollock et al., Citation2018). Five of the eight Indigenous studies included in this review of reviews were synthesized in one systematic review by Nasir et al. (Citation2016). These studies were restricted to three countries (Australia, Canada, and the United States) and primarily targeted young people, limiting the generalizability of results. Findings were consistent with those found more broadly, with increases in knowledge, attitude, self-efficacy, or behavioral intentions but limited reporting of behavioral change. The improved outcomes reported are likely because, in most cases, sufficient adaptation had taken place. There remains, however, ongoing concern about potential adverse effects, which are almost uniformly not measured, although previous evaluations in New Zealand have highlighted both cultural and clinical apprehensions (Oliver et al., Citation2015). The RCT study, which had no cultural adaptions, reported concerning negative outcomes for those attending GKT (Nasir et al., Citation2016).

Only four studies investigated the delivery of e-learning GKT; however, results suggest this training modality appears to show promising results, although measurement of long-term retention of outcomes is needed. E-learning GKT has considerable benefits for those unable to access in-person workshops and the potential to increase accessibility.

The longevity of positive gains in knowledge, self-efficacy, and attitude is unclear with evidence of a decay over time, although some evidence suggests that, despite decay, gains remain above pre-training measures (Holmes et al., Citation2021). Booster sessions may help to ensure gains in knowledge, self-efficacy, and attitudes are retained. Studies have also recommended that GKT gains might be retained via increased education and factors such as ongoing connections with trainees, reminders, and certification (Shtivelband et al., Citation2015). Cross et al. (Citation2010) found support for behavioral rehearsals in enhancing gains and recommended sending reminders via videos or web-based interactive practice.

All systematic reviews emphasize the need for more high-quality RCTs. Conducting RCTs in suicide prevention has been challenging for investigators who face methodological issues, such as the need for larger group size, acceptable control groups, and ethical issues such as withholding effective interventions (Reifels et al., Citation2018). Seeking to demonstrate a reduction in suicide rates is challenging because very large sample sizes are needed to ensure the statistical power to detect differences between groups, and, given the low base rates of suicide, this is difficult (Pearson et al., Citation2001).

Limitations

When interpreting the findings of this review of reviews, the potential for risk of bias should be considered. Most study designs were quasi-experimental and the 10 RCTs included were noted to be of low quality. The diversity of gatekeeper programs in terms of content, format, and evaluation measures makes it difficult to generalize findings across different contexts, populations, and intervention strategies.

Inclusion of systematic reviews was restricted to those that were peer reviewed and in English. Publication bias might exist given grey literature was not included.

Recommendations and Future Research

While extensive evidence exists from largely quasi-experimental studies demonstrating the positive impact of GKT on knowledge, skills, and self-efficacy, there is a need for more RCT studies to substantiate these findings. With increasing evidence demonstrating the important influence of knowledge, self-efficacy, and attitude on intervening and referral behaviors of gatekeeper trainees, RCTs could investigate the retention of gains in these domains, including the impact of booster/refresher sessions, and establish the impact on behavioral change.

Given the high rates of suicide in Indigenous populations, high-quality RCTs are also required to evaluate the effectiveness of GKT in Indigenous populations, as a stand-alone intervention and as part of a comprehensive suicide prevention strategy.

CONCLUSIONS

Overall, there was evidence across the systematic reviews for the immediate effects of GKT on trainees’ knowledge, skills, and self-efficacy but unclear evidence for improvement in attitudes and the transferability of training gains into behavioral application. Evidence suggests GKT is promising for Indigenous populations, but care is needed to ensure adequate adaptation to the specific cultural, historical, and social contexts of Indigenous populations with further research needed given most studies to date focus on youth and Northern American and Australian populations. No studies involving New Zealand Indigenous Māori were identified. Robust research into e-learning modalities and post-training (booster) interventions is warranted to ensure the sustainability of positive training outcomes. This is particularly crucial given the notable scarcity of research in this domain.

ETHICS STATEMENT

No institutional ethics approvals were required as this is a review of systematic reviews which are publicly available articles.

ESM 2 Table 4 ROBIS Template.xlsx

Download MS Excel (57.6 KB)ESM 1 TAble 2 Individual studies included in the identified systematic reviews.docx

Download MS Word (31.4 KB)ESM 3 Table 5 Characteristics of individual studies.pdf

Download PDF (396.2 KB)DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Denise Kingi-Uluave

Denise Kingi-Uluave, The University of Auckland Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences, Auckland, New Zealand.

Nalei Taufa

Nalei Taufa, The University of Auckland Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences, Auckland, New Zealand.

Ruby Tuesday

Ruby Tuesday, Moana Connect, Auckland, New Zealand.

Tania Cargo

Tania Cargo, The University of Auckland Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences, Auckland, New Zealand.

Karolina Stasiak

Karolina Stasiak, The University of Auckland Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences, Auckland, New Zealand.

Sally Merry

Sally Merry, The University of Auckland Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences, Auckland, New Zealand.

Sarah Hetrick

Sarah Hetrick, Department of Psychological Medicine, The University of Auckland Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences, Auckland, New Zealand.

REFERENCES

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Arensman, E., Coffey, C., Griffin, E., Van Audenhove, C., Scheerder, G., Gusmao, R., Costa, S., Larkin, C., Koburger, N., Maxwell, M., Harris, F., Postuvan, V., & Hegerl, U. (2016). Effectiveness of depression–suicidal behaviour gatekeeper training among police officers in three European regions: Outcomes of the optimising suicide prevention programmes and their implementation in Europe (OSPI-Europe) study. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 62(7), 651–660. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764016668907

- Banzi, R., Cinquini, M., Gonzalez-Lorenzo, M., Pecoraro, V., Capobussi, M., & Minozzi, S. (2018). Quality assessment versus risk of bias in systematic reviews: AMSTAR and ROBIS had similar reliability but differed in their construct and applicability. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 99, 24–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2018.02.024

- Bartgis, J., & Albright, G. (2016). Online role-play simulations with emotionally responsive avatars for the early detection of native youth psychological distress, including depression and suicidal ideation. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research, 23(2), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.5820/aian.2302.2016.1

- Beautrais, A., Fergusson, D., Coggan, C., Collings, C., Doughty, C., Ellis, P., & Surgenor, L. (2007). Effective strategies for suicide prevention in New Zealand: A review of the evidence. New Zealand Medical Journal, 120(1251):U2459. PMID: 17384687..

- Clifford, A. C., Doran, C. M., & Tsey, K. (2013). A systematic review of suicide prevention interventions targeting indigenous peoples in Australia, United States, Canada and New Zealand. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 463. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-463

- Coppens, E., Van Audenhove, C., Iddi, S., Arensman, E., Gottlebe, K., Koburger, N., Coffey, C., Gusmão, R., Quintão, S., Costa, S., Székely, A., & Hegerl, U. (2014). Effectiveness of community facilitator training in improving knowledge, attitudes, and confidence in relation to depression and suicidal behavior: Results of the OSPI-Europe intervention in four European countries. Journal of Affective Disorders, 165, 142–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.04.052

- Cross, W., Matthieu, M. M., Lezine, D., & Knox, K. L. (2010). Does a brief suicide prevention gatekeeper training program enhance observed skills? Crisis, 31(3), 149–159. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000014

- Deane, F. P., Capp, K., Jones, C., de Ramirez, D., Lambert, G., Marlow, B., Rees, A., & Sullivan, E. (2006). Two-year follow-up of a community gatekeeper suicide prevention program in an aboriginal community. The Australian Journal of Rehabilitation Counselling, 12(1), 33–36. https://doi.org/10.1375/jrc.12.1.33

- Ghoncheh, R., Gould, M. S., Twisk, J. W., Kerkhof, A. J., & Koot, H. M. (2016). Efficacy of adolescent suicide prevention e-learning modules for gatekeepers: A randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mental Health, 3(1), e8. https://doi.org/10.2196/mental.4614

- Henriksson, S., & Isacsson, G. (2006). Increased antidepressant use and fewer suicides in Jämtland County, Sweden, after a primary care educational programme on the treatment of depression. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 114(3), 159–167. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00822.x

- Higgins, J. P. T., & Green, S. (Eds.). (2011). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. The Cochrane Collaboration.

- Holmes, G., Clacy, A., Hermens, D. F., & Lagopoulos, J. (2021). The long-term efficacy of suicide prevention gatekeeper training: A systematic review. Archives of Suicide Research, 25(2), 177–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2019.1690608

- Hooven, C. (2013). Parents-CARE: A suicide prevention program for parents of at-risk youth. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 26(1), 85–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcap.12025

- Isaac, M., Elias, B., Katz, L. Y., Belik, S.-L., Deane, F. P., Enns, M. W., & Sareen, J. (2009). Gatekeeper training as a preventative intervention for suicide: A systematic review. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 54(4), 260–268. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674370905400407

- Johnson, L. A., & Parsons, M. E. (2012). Adolescent suicide prevention in a school setting: Use of a gatekeeper program. NASN School Nurse (Print), 27(6), 312–317. https://doi.org/10.1177/1942602x12454459

- Kuhlman, S. T. W., Walch, S. E., Bauer, K. N., & Glenn, A. D. (2017). Intention to enact and enactment of gatekeeper behaviors for suicide prevention: An application of the theory of planned behavior. Prevention Science, 18(6), 704–715. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-017-0786-0

- Mann, J. J., Apter, A., Bertolote, J., Beautrais, A., Currier, D., Haas, A., Hegerl, U., Lonnqvist, J., Malone, K., Marusic, A., Mehlum, L., Patton, G., Phillips, M., Rutz, W., Rihmer, Z., Schmidtke, A., Shaffer, D., Silverman, M., Takahashi, Y., … Hendin, H. (2005). Suicide prevention strategies: A systematic review. JAMA, 294(16), 2064–2074. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.294.16.2064

- Mo, P. K. H., Ko, T. T., & Xin, M. Q. (2018). School-based gatekeeper training programmes in enhancing gatekeepers’ cognitions and behaviours for adolescent suicide prevention: A systematic review. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 12, 29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-018-0233-4

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & The PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed1000097

- Montiel, C., & Mishara, B. L. (2023). Evaluation of the outcomes of the Quebec provincial suicide prevention gatekeeper training on knowledge, recognition of attitudes, perceived self-efficacy, intention to help, and helping behaviors. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 54(1), 108–121. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.13022

- Nasir, B. F., Hides, L., Kisely, S., Ranmuthugala, G., Nicholson, G. C., Black, E., Gill, N., Kondalsamy-Chennakesavan, S., & Toombs, M. (2016). The need for a culturally-tailored gatekeeper training intervention program in preventing suicide among Indigenous peoples: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 16(1), 357. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-016-1059-3

- Oliver, P., Spee, K., Akroyd, S., & Wolfgramm, T. (2015). Evaluation of the suicide gatekeeper training programmes. Ministry of Health. https://www.health.govt.nz/system/files/documents/publications/evaluation-suicide-prevention-gatekeeper-training-programmes.pdf

- Pearson, J. L., Stanley, B., King, C. A., & Fisher, C. B. (2001). Intervention research with persons at high risk for suicidality: Safety and ethical considerations. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 62(Suppl 25), 17–26.

- Pisani, A. R., Schmeelk-Cone, K., Gunzler, D., Petrova, M., Goldston, D. B., & Wyman, P. A. (2012). Associations between suicide high school students’ help-seeking and their attitudes and perceptions of social environment. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(7), 1106–1116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-102-9766-7

- Pollock, N. J., Naicker, K., Loro, A., Mulay, S., & Colman, I. (2018). Global incidence of suicide among Indigenous peoples: A systematic review. BMC Medicine, 16(1), 145. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-018-1115-6

- Reifels, L., Ftanou, M., Krysinska, K., Machlin, A., Robinson, J., & Pirkis, J. (2018). Research priorities in suicide prevention: Review of Australian research from 2010–2017 highlights continued need for intervention research. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(4), 807. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15040807

- Sareen, J., Isaak, C., Bolton, S. L., Enns, M. W., Elias, B., Deane, F., Munro, G., Stein, M. B., Chateau, D., Gould, M., & Katz, L. Y. (2013). Gatekeeper training for suicide prevention in First Nations community members: A randomized controlled trial. Depression and Anxiety, 30(10), 1021–1029. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22141

- Shea, B. J., Reeves, B. C., Wells, G., Thuku, M., Hamel, C., Moran, J., Moher, D., Tugwell, P., Welch, V., Kristjansson, E., & Henry, D. A. (2017). AMSTAR 2: A critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ, 358, j4008. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j4008

- Shtivelband, A., Aloise-Young, P. A., & Chen, P. Y. (2015). Sustaining the effects of gatekeeper suicide prevention training. Crisis, 36(2), 102–109. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000304

- Sjoblom, E., Ghidei, W., Leslie, M., James, A., Bartel, R., Campbell, S., & Montesanti, S. (2022). Centering Indigenous knowledge in suicide prevention: A critical scoping review. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 2377. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-14580-0

- Stone, D. M., & Crosby, A. E. (2014). Suicide prevention: State of the art review. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 8(6), 404–420. https://doi.org/10.1177/1559827614551130

- Szanto, K., Kalmar, S., Hendin, H., Rihmer, Z., & Mann, J. J. (2007). A suicide prevention program in a region with a very high suicide rate. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64(8), 914–920. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.64.8.914

- Torok, M., Calear, A. L., Smart, A., Nicolopoulos, A., & Wong, Q. (2019). Preventing adolescent suicide: A systematic review of the effectiveness and change mechanisms of suicide prevention gatekeeping training programs for teachers and parents. Journal of Adolescence, 73(1), 100–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.04.005

- van der Feltz-Cornelis, C. M., Sarchiapone, M., Postuvan, V., Volker, D., Roskar, S., Grum, A. T., Carli, V., McDaid, D., O’Connor, R., Maxwell, M., Ibelshäuser, A., Van Audenhove, C., Scheerder, G., Sisask, M., Gusmão, R., & Hegerl, U. (2011). Best practice elements of multilevel suicide prevention strategies: A review of systematic reviews. Crisis, 32(6), 319–333. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000109

- Westerman. (2007). Summary of results from Indigenous suicide prevention programs delivered by Indigenous psychological services. https://indigenouspsychservices.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Suicide-Intervention-Program-Outcomes.pdf

- Whiting, P., Savović, J., Higgins, J. P. T., Caldwell, D. M., Reeves, B. C., Shea, B., Davies, P., Kleijnen, J., Churchill, R., & The ROBIS Group. (2016). ROBIS: A new tool to assess risk of bias in systematic reviews was developed. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 69, 225–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.06.005

- World Health Organization. (2014). Preventing suicide: A global imperative. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241564779

- World Health Organization. (2018). National suicide prevention strategies: Progress, examples and indicators. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241515016

- Wyman, P. A., Brown, C. H., Inman, J., Cross, W., Schmeelk-Cone, K., Guo, J., & Pena, J. B. (2008). Randomized trial of a gatekeeper program for suicide prevention: 1-year impact on secondary school staff. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(1), 104–115. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.104

- Yonemoto, N., Kawashima, Y., Endo, K., & Yamada, M. (2019). Gatekeeper training for suicidal behaviors: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 246, 506–514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.12.052

- Zinzow, H. M., Thompson, M. P., Fulmer, C. B., Goree, J., & Evinger, L. (2020). Evaluation of a brief suicide prevention training program for college campuses. Archives of Suicide Research, 24(1), 82–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2018.1509749