Abstract

Background

The term “safety management planning” can be thought of as having evolved to constitute a number of different intervention types and components used across various clinical settings with various populations. This poses a challenge for effective communication between clinicians and likely variability in the clinical effectiveness of these interventions.

Aim

This PRISMA Scoping Review aims to review the literature to ascertain which intervention components and characteristics currently fall under this umbrella term as well as in which contexts the plans are delivered and who is involved in the process.

Method

Published research studies in PsycINFO, CINAHL Plus, MEDLINE, Science Direct and Web of Science were reviewed. Grey literature was searched using the databases Base and OpenGrey as well as through the search engine Google.

Results

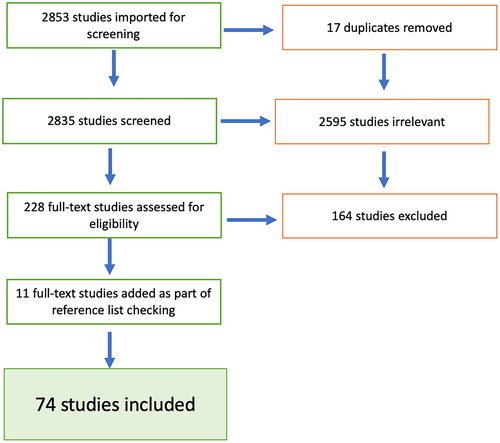

2853 abstracts were initially identified for screening and 74 pieces of literature informed the final review, with 54 derived from the published academic literature and 20 from the grey literature. Results indicated that the safety plans are used with a wide variety of populations and often include components related to identifying warning signs, internal coping strategies, accessing social professional support amongst other components.

Conclusion

Although most safety management plans described appeared to be based on specific interventions, there was a large amount of heterogeneity of components and characteristics observed. This was particularly the case with regards to safety management planning within the grey literature.

This review explored what is currently meant by the term “safety management planning” within the academic and grey literature.

While the majority of safety management planning interventions are based on specific researched interventions, many safety management planning tools vary in their characteristic and components.

Evidence from within the grey literature suggests the use of safety management planning in a community setting, without clinical supervision.

HIGHLIGHTS

Suicide and self-harm are major public health concerns with approximately 800,000 individuals around the world dying by suicide every year (World Health Organization [WHO], Citation2019). Rates of individuals who attend hospital following incidents of self-harm have risen in recent years, with some evidence suggesting that rates may be significantly higher than hospital presentation rates suggest (Clements et al., Citation2016; McIntyre et al., Citation2021). Self-harm is often repeated (Carroll et al., Citation2014; Cully et al., Citation2021) and is indicative not only of an individual’s distress, but is also a key risk factor for later completed suicide (Hawton et al., Citation2015). Self-harm is defined by National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines (CG16 and 133), as “any act of self-poisoning or self-injury carried out by a person, irrespective of motivation” (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [NICE], 2011, p. 4).

There is evidence to support the use of psychosocial interventions with those at risk of self-harm (see Witt et al., Citation2021 for review) and several approaches to addressing acute risk of self-harm have been developed particularly within the cognitive behavioral therapy orientation (Bryan, Citation2010; Jobes, Citation2016; Rudd et al., Citation2006; Stanley & Brown, Citation2012). These include stand-alone interventions formed on the assumption that if individuals can be given tools or skills which enable them to resist or decrease suicidal urges for brief periods of time, risk of self-harm is likely to decrease (Daigle, Citation2005). One such stand-alone intervention which has shown good clinical utility is that of safety management planning (SMP).

The Safety Planning Intervention (SPI) is one such SMP intervention. Defined by Stanley and Brown (Citation2012) as “a brief intervention that can lessen the risk for a suicide attempts and self-harm by identifying potential coping strategies and supportive personal and professional contacts that can be utilized during a suicidal crisis” (Stanley & Brown, Citation2012, p. 257), there are six steps that are utilized as part of the intervention: (1) identifying personal warning signs of an impending suicidal crisis; (2) identifying internal coping strategies; (3) identifying social distractions and social support; (4) identifying social contacts the client can contact to help resolve a suicidal crisis; (5) identifying professionals and/or agencies who can be contacted when the client is in crisis and the previous steps have failed to resolve the crisis; (6) identifying ways to make the client’s immediate environment safe through limiting access to potentially lethal suicide attempt means (Stanley & Brown, Citation2012).

A number of interventions which are related in structure and content to the SPI have also been developed and are referred to within this review as falling under the term of “safety management planning interventions (SMPIs).” The Crisis Response Planning intervention (Bryan & Rudd, Citation2018) is part of a cognitive behavioral approach targeted at reducing risk of self-harm. The intervention consists of helping an individual to identify what specifically triggers a crisis, use skills to regulate emotion and to obtain emergency medical care, if needed. This is done through a collaborative approach with a clinician and the steps are written on a small piece of card, which the individual then takes with them to refer to when needed. A further conceptually similar SMP approach is included within the Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicidality (CAMS) approach for individuals at risk of self-harm (Jobes, Citation2016). The CAMS stabilization plan seeks to identify what an individual could do to cope more effectively during a crisis, who they could contact during a crisis as well as removing items from the environment with which they could harm themselves. It also advises identifying the individual’s reasons for living as well as their reasons for wanting to die. SMPIs are frequently utilized in clinical practice for three key reasons: (i) they are effective at reducing self-harm/suicide attempts; (ii) they are acceptable to individuals who have suicidal ideation or who self-harm; (iii) they are relatively easy to incorporate into clinical practice. A recent meta-analysis by Nuij and colleagues which evaluated the effectiveness of SMPIs in reducing suicidal behavior and ideation found that SMPIs were effective at reducing self-harm behavior in adults although it was noted that there did not appear to be a significant effect on suicidal ideation (Nuij et al., Citation2021). SMPs appear to be acceptable to both the clients they are delivered to, as well as by the clinicians who deliver them, with research indicating that adult clients find SMPs helpful in decreasing their risk of self-harm and negative emotional states (Bryan et al., Citation2018; Stanley et al., Citation2021) and emergency department medical staff appearing to find the interventions useful for increasing patient safety, encouraging connection with follow-up services, and increasing staff confidence in safe discharge (Chesin et al., Citation2017). SMPs can also be easily integrated into routine clinical practice without the need for significant additional resources or reconfiguration of services (McCabe et al., Citation2018) and have been successfully incorporated into settings, such as psychiatric inpatient settings, military and correctional settings, and schools (Erbacher et al., Citation2014; Stanley & Brown, Citation2012).

In addition, SMPs can be integrated within various treatment protocols and interventions including brief cognitive behavioral therapy (Bryan & Rudd, Citation2018; Rudd et al., Citation2015) and trauma focused therapies for individuals with PTSD (Rozek & Bryan, Citation2020). It is for these reasons, SMP has been identified as “best practice” by the US Suicide Prevention Resource Center and is widely used in mental health services internationally.

Since their conception, SMPs have been seen to grow and develop over time alongside new technologies. SMPs via web or app based platforms have shown promising results in both the USA and Australia (Melvin et al., Citation2019). As individuals who complete the original SPI are encouraged to keep a paper copy of the plan to hand so that it is immediately accessible in the event of a crisis (Bryan, Citation2010; Rudd et al., Citation2006; Stanley & Brown, Citation2012), the use of a mobile phone app can facilitate immediate accessibility. The BeyondNow app (Melvin, Citation2016), based on the Stanley and Brown (Citation2012) intervention, is one such example which provides a platform for individuals to create, edit, access, and share their personalized safety management plan. Users can list warning signs, reasons to live, ways to limit access to lethal means, coping strategies, and personal and professional contacts within the app.

Alongside the variation which is seen across conceptually similar approaches and within their delivery, there is likely a considerable amount of variation observed within these approaches. Stanley and Brown (Citation2012) advised that safety plans should not be completed in a one-size-fits-all approach but should be adapted to the individual’s personal circumstances. As such, SMPs by necessity are often adapted according to local service guidelines as well as clinical/professional judgment. In addition, interventions continue to evolve and grow in response to advances of knowledge in the area. For example, a study by Bryan et al. (Citation2018) found that enhanced crisis response plans, which included an overt discussion of the client’s reasons for living, included on the index card reduced the likelihood of inpatient admission, when compared to a standard crisis response plan intervention. The intervention is also likely to be impacted by service and clinician level factors with research indicating that those delivering SMPs not always having had formal training in its delivery, and as such, fidelity to local procedure is likely to be variable (Green et al., Citation2018). A study by Green et al. (Citation2018) found that many of the SMPs reviewed in their study lacked particular items and were of poor quality.

The inherent flexibility of the SMP approach, alongside considerable variations across and within conceptually similar interventions, is a challenge for effective communication between clinicians because the term “safety planning’ does not necessarily denote the use of any particular intervention component or group of components. This variability is also a challenge for research on the effectiveness of SMPs and in particular the value of particular components. For example, although evidence suggests lethal means restriction can reduce suicide attempts and deaths (e.g. Hawton et al., Citation2012; Yip et al., Citation2012), there is less evidence suggesting that other commonly used components of safety planning interventions (e.g. the use of internal coping strategies, disclosing thoughts to supportive friends or family) can do the same (Green et al., Citation2018).

This review seeks to explore what currently falls under the umbrella term of “safety management planning” and related approaches with the aim of developing a greater understanding of how these interventions are currently conceptualized within the literature. The review also aims to examine how safety management planning is currently understood in the grey literature, including through published material which may be available for personal use on the internet.

METHOD

A PRISMA-ScR scoping review was conducted in order to ascertain which intervention components currently fall under the umbrella of “safety management planning” and when and how SMP intervention components are currently used in practice. A scoping review methodology was used in order to capture the scope of the literature available on the topic as well as due to the exploratory nature of the research questions (Tricco et al., Citation2018). The methodology for this scoping review is guided by Arksey and O'Malley (Citation2005) five-stage framework which includes the following step: identify the research question, identify articles, study selection, extract data, and summarize and report the data.

Identifying the Research Question

The review aimed to identify descriptions of SMP in both the published academic literature as well as grey literature, including examples of safety planning templates available for use by the public online. To ensure that a wide range of literature pertaining to the topic was captured, we posed the following research questions:

What information is typically included in the formation of a safety management plan?

Who is involved in the construction and utilization of a safety management plan?

What context is SMP used and with which specific client groups?

What adjunctive advice or guidance is typically offered alongside a SMP intervention?

Identifying Relevant Studies

The review was conducted in line with PRISMA guidelines (2009). The review sought to identify any examples from the literature where a SMP intervention was described. Searches were performed by the first author using the following electronic bibliographic databases: PsycINFO, CINAHL Plus, MEDLINE, Science Direct and Web of Science for studies published up to the date the searches are run. The searches were conducted on June 28, 2020. A review of grey literature, was conducted in order to identify any examples of safety management planning tools available outside the academic literature. This encompassed information in the public domain available on the internet. The search was conducted using the online databases: Base and OpenGrey. A Google search was also conducted and the first 50 websites of results included (in line with previous reviews, e.g. Kelly et al., Citation2010). Additional literature was identified through the hand-searching of reference lists of key included studies and reviews.

Search terms were selected based on previous reviews, from the academic literature on the topic and from a search of the thesaurus function on relevant databases. Search terms were additionally derived from the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) index in MEDLINE. Supplementary material shows the search strings used for searching each electronic database. Consultation was sought from a librarian with expertise in academic reviews.

References were extracted and imported to the Covidence reference management system, where duplicates were removed. In the first instance the first and second author screened all retrieved titles and abstracts independently. Any disagreements were discussed between reviewers. Following this, the first author read independently the full texts of all literature deemed eligible for inclusion from the first step. Any disagreements between reviewers were discussed.

Inclusion Criteria

With regards to study selection, the following inclusion criteria were used: (1) Articles from all geographical locations and settings; (2) Publications in English; (3) Publications published since 2000; (4) All age groups of participants; (5) Literature containing information pertaining to the creation, utility or effectiveness of a safety management planning intervention for individuals or groups at risk of self-harm including peer-reviewed primary research studies and reviews (including but not limited to systematic reviews, scoping reviews, meta-analyses and grey literature, encompassing information in the public domain available on the internet, such as existing clinical guidelines or websites containing safety planning advice).

The following exclusion criteria were used:

Publications published before 2000;

Publications focusing on safety planning interventions from outside the risk of self-harm space (e.g. safety planning for sufferers of domestic violence, safety planning for psychosis);

Publications which did not describe the components of the safety planning tool.

Data Extraction

A data extraction template was developed in the review management software, Covidence (see Supplemental Appendix B). The extraction was completed by reviewer one (MOC) independently and then 20% of the studies were independently extracted by the second reviewer (EH). Any disagreements were discussed between the reviewers.

The characteristics and components of SMP tools and interventions were classified in terms of the contexts and client groups with which they are usually used, information included, individuals who participate in the creation and utilization of the plans, adjunct advice or guidance offered, and the theoretical models and approaches drawn upon. Where descriptive language differed relating to overlapping components, components were grouped together semantically. Characteristics of the literature was summarized in tables and described narratively.

RESULTS

Search Results

As illustrated in , search results from 6 databases and a Google search retrieved 2853 citations. After removing 17 duplicates, 2835 unique titles and abstracts remained. These titles and abstracts were reviewed and following this, 2595 citations were excluded (see ). The full text of 228 citations was then read, with 63 being deemed appropriate for inclusion. 11 additional studies were identified through backwards reference checking. In total, 74 publications were included in the synthesis. Supplemental Appendix C shows the full list of the included literature.

Description of Included Studies and Grey Literature

As presented in , the majority of the literature included were published journal articles (n = 54, 73%). Although studies were published in 12 countries, over half of the were published in the USA. More than half of the studies were published between 2016 and 2020 (59%). 30% of the studies reviewed referred to safety management plans carried out within a clinical outpatient setting. Nearly a quarter of the literature referred to safety management planning conducted with a general adult population (24%) with a smaller percentage referring to an adolescent or young adult population (19%) and a veteran population (16%). Just over half of the literature (54%) referred to safety planning as a discussion or paper based activity with 15% referring to safety management planning apps.

TABLE 1. Characteristics of the included literature.

Within the grey literature, three quarters of safety management planning tools were targeted toward individuals themselves who may complete the document without the guidance of a mental health professional (75%). The grey literature contained material from a variety of sources including mental health charity websites (35%), Veterans’ Affairs Organizations (n = 7) and the UK National Health Service (NHS) (15%).

Characteristics of Safety Management Planning

The included literature assessed 59 different descriptions of SMP tools. 70% of these tools were judged to be based on the Stanley and Brown (Citation2012) Safety Planning Intervention. All of the literature mentioned that SMP should be a collaborative process involving the service user in the creation of the plan either explicitly or in the case of some of the grey literature, this was implicit in the design of the plan. A small proportion of the academic literature makes specific reference to sharing a safety management plan with a friend or family member (18%). This proportion was similar within the grey literature. Within studies and literature concerning adolescents, this rose to 44% of studies recommending that the plan be shared with a family member or another trusted adult.

Within the academic literature, 38% of studies indicated that the individual in crisis should receive a written copy of their plan or this was implied by the use of a mobile phone app. This percentage was substantially higher within the grey literature (80%). A small percentage of studies (13.5%) referred to the importance of ensuring the plan was updated in the future. Within the grey literature, a similar percentage referred to the importance of revising and following up the plan at a later date. See .

TABLE 2. Characteristics of safety management planning.

Components of Safety Management Planning

The majority of SMP tools contained a section related to identifying warning signs or triggers (see ). Most safety planning tools also referred to identifying internal coping strategies, social contacts for assistance in resolving the suicidal crisis and professional and agency contacts to assist in resolving suicidal crisis. A smaller percentage of plans referred to steps involving the identification of social contacts and social settings for distraction and support, with a smaller percentage still referred to steps taken to restrict access to means that one may use to self-harm and to keeping the environment safe. Some other components of safety management plans included sections related to reasons for living and the creation of a hope box. A hope box is defined as a physical representation of an individual’s reasons for living. Items included in an individual’s hope box will vary from person to person but typically might include reminders of previous successes, positive life experiences, existing coping resources, and current reasons for living (Ghahramanlou-Holloway et al., Citation2012). Within the grey literature, all tools referred to seeking support from social contacts whereas within the academic literature only 90% of tools did so. The grey literature also contained fewer tools that encouraged help seeking from professionals or agencies (84.2%) and which referenced reasons for living when compared to the academic literature.

TABLE 3. Components of safety management planning.

DISCUSSION

This scoping review aimed to determine the components and characteristics of safety management planning interventions as reported in the empirical and grey literature. 54 studies were identified that contained descriptions of safety management planning tools and interventions and 20 pieces of grey literature were identified.

The Stanley and Brown (Citation2008) guidelines for the SPI describe six steps as part of their safety planning intervention. The majority of SMPs described included reference to three of these steps (identifying personal warning signs, identifying internal coping strategies, and identifying people the individual can contact to help resolve a suicidal crisis). A smaller percentage of safety management plans referred to the inclusion of external coping strategies, referred to in the Stanley & Brown intervention as “identifying social distractors and social support.” These coping strategies refer to strategies employed by an individual which involve external influence (for example another person or a social situation or calming place) to assist the individual in distracting themselves from the distressing thoughts and feelings. External coping strategies often involve the use of another person, but unlike subsequent steps, the individual does not need to disclose the function of their reaching out in this situation. This may be beneficial for a number of reasons including decreasing perceived burdensomeness. The Interpersonal Theory of Suicide (Van Orden et al., Citation2010) proposes that the most dangerous form of suicidal desire is caused by the simultaneous presence of two interpersonal constructs—thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness (and hopelessness about these states). Therefore the involvement of another person, without the disclosure of the suicidal thought, may allow the individual to benefit from the short term decrease in suicidal ideation offered by distraction and socializing (Stanley et al., Citation2021), without increasing their perceived burdensomeness.

It is noteworthy that qualitatively, the language used differed between the academic and grey literature. The academic literature tended to refer to use more formal language than the grey literature and is more likely to explain the terms that are used. For example, one publication from the grey literature describes warning signs as follows: “What warning signs or triggers are there that make me feel more out of control?” as opposed to the Stanley and Brown template which simply states, “Recognising Warning Signs.” Overall, the plans identified as part of the grey literature might be described as being more “person-centred” or “non-technical” but might also be described as being more general. For example, what is referred to as “internal” and “external” coping strategies in the academic literature has been reduced to the following question in one example from the grey literature: “What have I done in the past that helped? What ways of coping do I have?” This difference is most likely related to the expectation in the academic literature that SMP will be completed with the support of a mental health professional, whereas the grey literature plan assumes no such professional intervention. Research indicates that language adapted to the service user group is more likely to facilitate engagement (Aggarwal et al., Citation2016). However, it is possible that over-simplification of language and instruction could lead to reduced efficacy and clarity, particularly with interventions utilized without the guidance of a mental health professional with familiarity in psycho-social interventions.

Studies evaluating SMP interventions generally refer to a named intervention (e.g. SPI or Crisis Response Planning) which include overlapping but slightly different components. For example, over half of both the academic and the grey literature plans referred to the removal of items from the person’s environment with which they could harm themselves. Research suggests that suicidal crises are often relatively short-lived, tend to subside over time and have an ebb and flow pattern (Daigle, Citation2005). Evidence from research on near lethal suicide attempts suggests that a large proportion of suicide attempts are an impulsive response that would not have occurred if the means had not been readily available (Hawton, Citation2005). As such, lethal means restriction has been shown to have a strong empirical foundation (Mann et al., Citation2021). Future research may seek to examine the effects of the inclusion of items related to means restriction in SMP procedure, to ascertain the effectiveness of its inclusion within the approach. More broadly, future research may also seek to explore which particular intervention components are most important for use within the approach, and if this varies across settings and clinical populations.

It is noteworthy that a large percentage of SMPs described in the grey literature were targeted at individuals who were not necessarily under the care of a clinician or linked in with a mental health service. Furthermore, over 15% of the grey literature included reference to a step involving identifying professionals and/or agencies who could be contacted when the individual is in crisis. The academic literature describes SMP as a collaborative process completed by an individual at risk as well as a trained mental health professional. As such, SMP completed outside of the realms of such a relationship have not been supported by research and therefore the efficacy and suitability of such plans are unknown. Furthermore, as research indicates that individuals in crisis benefit from accessing appropriate services (Atkinson et al., Citation2019; Campo, Citation2009) it is recommended that agencies who distribute SMP tools online or in other formats be aware of this distinction and emphasize the importance of an individual linking in with appropriate services should a mental health crisis arise.

Roughly a quarter of the plans examined included sections related to reasons for living (25.4%). This number was even higher amongst the grey literature (32%). Reasons for living are related to an individual’s perceived meaning in life and might include beliefs, memories or people that decrease the individual’s desire for death (Linehan et al., Citation1983). Determining reasons for living has been shown to reduce suicidal cognitions (Bakhiyi et al., Citation2016) and many recent empirically-supported interventions shown to reduce suicidality directly target identifying and enhancing reasons for living (e.g., Bryan & Rudd, Citation2018). This includes crisis response planning (Bryan & Rudd, Citation2018), which has been recommended by the USA’s Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defence (2019). The inclusion within the grey literature of reasons for living in addition to steps typically included in the Stanley and Brown (Citation2012) SPI suggest a move among health and non-governmental organizations to provide individuals in crisis with a range of strategies which might reduce suicidal crises, however it is noteworthy that within the academic literature fewer studies have examined the effectiveness of such hybrid interventions and so conclusions may not be drawn about the effectiveness or suitability of such plans.

This scoping review was guided by a rigorous protocol and utilized a search strategy that included 6 electronic databases. To ensure a thorough search of the literature, the reference lists of 10 studies were searched and 4 google searches were carried out to identify any additional relevant grey material. Each title and abstract were reviewed by two independent reviewers. The use of the bibliographic manager (Mendeley) in combination with systematic review management software (Covidence) ensured that all literature was properly accounted for during the process. However, despite best efforts, this review may not have identified all relevant literature. Search terms were devised using the thesaurus feature available on each database but it is possible that some publications regarding safety planning used terms that were not included in our searches. The review searched only literature available in the English language and as such literature published in other languages has been missed. Furthermore, the search engine “google” was used in this review which although observed to be a useful way to search for supplementary grey literature which may not be sourced through other methods (Hagstrom, 2015), there are limitations associated with its usage. For example, search results can depend on various elements, such as the search engine’s page ranking, or the user’s habitual search patterns. Although steps were taken to minimize these limitations, in line with Hagstrom (2015), it is possible that more extensive literature could have been retrieved.

In conclusion, this review found that although heterogeneity of components and characteristics were observed across SMPs, the majority of the plans contained reference to similar intervention components, with most examples appearing to be based on specific interventions. SMPs have been used with a wide variety of populations (including adolescents, adults, veterans, military personal, refugees) across a wide range of settings (inpatient and outpatient care, college campus, emergency departments) and were found to be used both as stand-alone interventions as well as part of wider treatment protocols.

O'ConnorM SMP Scoping Review - Appendices.docx

Download MS Word (40.6 KB)DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Maeve O’Connor

Maeve O'Connor, School of Psychology, University College Dublin, Ireland.

Aine Sutton

Aine Sutton, School of Psychology, Queen's University Belfast, UK.

Eilis Hennessy

Eilis Hennessy, School of Psychology, University College Dublin, Ireland.

REFERENCES

- Aggarwal, N. K., Pieh, M. C., Dixon, L., Guarnaccia, P., Alegría, M., & Lewis-Fernández, R. (2016). Clinician descriptions of communication strategies to improve treatment engagement by racial/ethnic minorities in mental health services: A systematic review. Patient Education and Counseling, 99(2), 198–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2015.09.002

- Arksey, H., & O'Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Atkinson, J.-A., Page, A., Heffernan, M., McDonnell, G., Prodan, A., Campos, B., Meadows, G., & Hickie, I. B. (2019). The impact of strengthening mental health services to prevent suicidal behaviour. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 53(7), 642–650. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867418817381

- Bakhiyi, C. L., Calati, R., Guillaume, S., & Courtet, P. (2016). Do reasons for living protect against suicidal thoughts and behaviors? A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 77, 92–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.02.019

- Bryan, C. J. (2010). Managing suicide risk in primary care. Springer Publishing Company.

- Bryan, C. J., & Rudd, M. D. (2018). Brief cognitive-behavioral therapy for suicide prevention. Guilford Publications.

- Bryan, C. J., Mintz, J., Clemans, T. A., Burch, T. S., Leeson, B., Williams, S., & Rudd, M. D. (2018). Effect of crisis response planning on patient mood and clinician decision making: A clinical trial with suicidal US soldiers. Psychiatric Services, 69(1), 108–111. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201700157

- Bryan, C. J., Mintz, J., Clemans, T. A., Leeson, B., Burch, T. S., Williams, S. R., Maney, E., & Rudd, M. D. (2017). Effect of crisis response planning vs. contracts for safety on suicide risk in US Army soldiers: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Affective Disorders, 212, 64–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.01.028

- Campo, J. V. (2009). Youth suicide prevention: Does access to care matter? Current Opinion in Pediatrics, 21(5), 628–634. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOP.0b013e32833069bd

- Carroll, R., Metcalfe, C., & Gunnell, D. (2014). Hospital presenting self-harm and risk of fatal and non-fatal repetition: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One, 9(2), e89944. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0089944

- Chesin, M. S., Stanley, B., Haigh, E. A., Chaudhury, S. R., Pontoski, K., Knox, K. L., & Brown, G. K. (2017). Staff views of an emergency department intervention using safety planning and structured follow-up with suicidal veterans. Archives of Suicide Research, 21(1), 127–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2016.1164642

- Clements, C., Turnbull, P., Hawton, K., Geulayov, G., Waters, K., Ness, J., Townsend, E., Khundakar, K., & Kapur, N. (2016). Rates of self-harm presenting to general hospitals: A comparison of data from the Multicentre Study of Self-Harm in England and Hospital Episode Statistics. BMJ Open, 6(2), e009749. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009749

- Cully, G., Corcoran, P., Leahy, D., Cassidy, E., Steeg, S., Griffin, E., Shiely, F., & Arensman, E. (2021). Factors associated with psychiatric admission and subsequent self-harm repetition: A cohort study of high-risk hospital-presenting self-harm. Journal of Mental Health, 30(6), 751–759. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2021.1979488

- Daigle, M. S. (2005). Suicide prevention through means restriction: Assessing the risk of substitution: A critical review and synthesis. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 37(4), 625–632. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2005.03.004

- Erbacher, T. A., & Singer, J. B. (2018). Suicide risk monitoring: The missing piece in suicide risk assessment. Contemporary School Psychology, 22(2), 186–194.

- Erbacher, T. A., Singer, J. B., & Poland, S. (2014). Suicide in schools: A practitioner’s guide to multi-level prevention, assessment, intervention, and postvention. Routledge.

- Ghahramanlou-Holloway, M., Cox, D. W., & Greene, F. N. (2012). Post-admission cognitive therapy: A brief intervention for psychiatric inpatients admitted after a suicide attempt. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 19(2), 233–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2010.11.006

- Green, J. D., Kearns, J. C., Rosen, R. C., Keane, T. M., & Marx, B. P. (2018). Evaluating the effectiveness of safety plans for military veterans: Do safety plans tailored to veteran characteristics decrease suicide risk?. Behavior Therapy, 49(6), 931–938. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2017.11.00530316491

- Hagstrom, C., Kendall, S., & Cunningham, H. (2015). Googling for grey: Using Google and Duckduckgo to find grey literature. Abstracts of the 23rd Cochrane Colloquium. Cochrane database systematic reviews supplements (pp. 1–327).

- Hawton, K. (2005). Restriction of access to methods of suicide as a means of suicide prevention. In Hawton, K. (Ed.), Prevention and treatment of suicidal behaviour from Science to practice. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, pp. 279-291.

- Hawton, K., Bergen, H., Cooper, J., Turnbull, P., Waters, K., Ness, J., & Kapur, N. (2015). Suicide following self-harm: Findings from the multicentre study of self-harm in England, 2000–2012. Journal of Affective Disorders, 175, 147–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.12.062

- Hawton, K., Saunders, K. E., & O'Connor, R. C. (2012). Self-harm and suicide in adolescents. Lancet, 379(9834), 2373–2382. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60322-5

- Jobes, D. A. (2016). Managing suicidal risk: A collaborative approach. Guilford Publications.

- Kelly, C. M., Jorm, A. F., & Kitchener, B. A. (2010). Development of mental health first aid guidelines on how a member of the public can support a person affected by a traumatic event: A Delphi study. BMC Psychiatry, 10(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-10-49

- Linehan, M. M., Goodstein, J. L., Nielsen, S. L., & Chiles, J. A. (1983). Reasons for staying alive when you are thinking of killing yourself: The reasons for living inventory. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 51(2), 276–286. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-006X.51.2.276

- Mann, J. J., Michel, C. A., & Auerbach, R. P. (2021). Improving suicide prevention through evidence-based strategies: A systematic review. American Journal of Psychiatry, 178(7), 611–624. appi-ajp. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20060864

- McCabe, R., Garside, R., Backhouse, A., & Xanthopoulou, P. (2018). Effectiveness of brief psychological interventions for suicidal presentations: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), 120. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1663-5

- McIntyre, A., Tong, K., McMahon, E., & Doherty, A. M. (2021). COVID-19 and its effect on emergency presentations to a tertiary hospital with self-harm in Ireland. Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine, 38(2), 116–122. https://doi.org/10.1017/ipm.2020.116

- Melvin, G. A. (2016). BeyondNow-suicide safety planning application. Monash University.

- Melvin, G. A., Gresham, D., Beaton, S., Coles, J., Tonge, B. J., Gordon, M. S., & Stanley, B. (2019). Evaluating the feasibility and effectiveness of an Australian safety planning smartphone application: A pilot study within a tertiary mental health service. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 49(3), 846–858.

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151(4), 264–269, W64. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). (2011). Self-harm in over 8s: Long-term management. Clinical guideline [CG133]. NICE. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg133.

- Nuij, C., van Ballegooijen, W., de Beurs, D., Juniar, D., Erlangsen, A., Portzky, G., O'Connor, R. C., Smit, J. H., Kerkhof, A., & Riper, H. (2021). Safety planning-type interventions for suicide prevention: Meta-analysis. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 219(2), 419–426. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2021.50

- Rozek, D. C., & Bryan, C. J. (2020). Integrating crisis response planning for suicide prevention into trauma-focused treatments: A military case example. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 76(5), 852–864. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22920

- Rudd, M. D., Berman, A. L., Joiner, T. E., Nock, M. K., Silverman, M. M., Mandrusiak, M., Van Orden, K., & Witte, T. (2006). Warning signs for suicide: Theory, research, and clinical applications. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 36(3), 255–262. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.2006.36.3.255

- Rudd, M. D., Bryan, C. J., Wertenberger, E. G., Peterson, A. L., Young-McCaughan, S., Mintz, J., Williams, S. R., Arne, K. A., Breitbach, J., Delano, K., Wilkinson, E., & Bruce, T. O. (2015). Brief cognitive-behavioral therapy effects on post-treatment suicide attempts in a military sample: Results of a randomized clinical trial with 2-year follow-up. American Journal of Psychiatry, 172(5), 441–449. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14070843

- Stanley, B., Martínez-Alés, G., Gratch, I., Rizk, M., Galfalvy, H., Choo, T.-H., & Mann, J. J. (2021). Coping strategies that reduce suicidal ideation: An ecological momentary assessment study. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 133, 32–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.12.01233307352

- Stanley, B., Brown, G. K. (2008). Safety plan treatment manual to reduce suicide risk: Veteran version. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/VA_Safety_plan ning_manual.pdf

- Stanley, B., & Brown, G. K. (2012). Safety planning intervention: A brief intervention to mitigate suicide risk. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 19(2), 256–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2011.01.001

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O'Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

- Van Orden, K. A., Witte, T. K., Cukrowicz, K. C., Braithwaite, S. R., Selby, E. A., & Joiner, T. E. (2010). The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychological Review, 117(2), 575–600. https://doi.org/10.1037/a001869720438238

- Witt, K. G., Hetrick, S. E., Rajaram, G., Hazell, P., Salisbury, T. L. T., Townsend, E., & Hawton, K. (2021). Psychosocial interventions for self-harm in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 4(4), CD013668.

- World Health Organization. (2019). Suicide in the world: Global health estimates (p. 32). WHO.

- Yip, P. S., Caine, E., Yousuf, S., Chang, S. S., Wu, K. C. C., & Chen, Y. Y. (2012). Means restriction for suicide prevention. Lancet, 379(9834), 2393–2399. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60521-2