Abstract

Introduction

Effective suicide prevention interventions are infrequently translated into practice and policy. One way to bridge this gap is to understand the influence of theoretical determinants on intervention delivery, adoption, and sustainment and lessons learned. This study aimed to examine barriers, facilitators and lessons learned from implementing complex suicide prevention interventions across the world.

Methods and materials

This study was a secondary analysis of a systematic review of complex suicide prevention interventions, following updated PRISMA guidelines. English published records and grey literature between 1990 and 2022 were searched on PubMed, CINAHL, PsycINFO, ProQuest, SCOPUS and CENTRAL. Related reports were organized into clusters. Data was extracted from clusters of reports on interventions and were mapped using the updated Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research.

Results

The most frequently-reported barriers were reported within the intervention setting and were related to the perceived appropriateness of interventions within settings; shared norms, beliefs; and maintaining formal and informal networks and connections. The most frequently reported facilitators concerned individuals’ motivation, capability/capacity, and felt need. Lessons learned focused on the importance of tailoring the intervention, responding to contextual needs and the importance of community engagement throughout the process.

Conclusion

This study emphasizes the importance of documenting and analyzing important influences on implementation. The complex interplay between the contextual determinants and implementation is discussed. These findings contribute to a better understanding of barriers and facilitators salient for implementation of complex suicide prevention interventions.

INTRODUCTION

Suicide is inextricably linked with broader contextual issues such as matters of social justice and equity (Fitzpatrick, Citation2018; Westefeld, Citation2020). The complexity and challenges involved in preventing suicidal behaviors is, therefore, well documented. A complex, public health approach to suicide prevention, involving multiple strategies operating at different levels of the social ecology, has been found to be helpful in targeting a complex interplay of risk factors (Yip & Tang, Citation2021). In addition, scientific investigations to demonstrate effectiveness of such public health interventions must reflect this complexity (Hawton & Pirkis, Citation2017; Skivington et al., Citation2021). However, the evidence base for effective suicide prevention is far from convincing (Platt & Niederkrotenthaler, Citation2020; Zalsman et al., Citation2016). Important questions such as – What makes an intervention work? How do we implement and disseminate what is known to achieve a population level impact? remain unaddressed (Wilkins et al., Citation2013). Therefore, a gap between evidence-practice exists, which can take many forms such as slow uptake of effective interventions, continued uptake of interventions that are ineffective and/or failure to stay updated with changes in the ethos of care (Presseau et al., Citation2019).

Some scholars critique the origin and evolution of the term evidence base and call for a non-linear way of looking at its relationship with practice (Green, Citation2008; Kessler & Glasgow, Citation2011). Green and Nasser (Citation2017) discuss the issue of inadequate consideration of external validity within research and critique the emphasis on greater rigor or scientific control over generalizability of results to populations, settings, and conditions. It is suggested that the problem of relevance of research for practice and policy could be addressed by emphasizing best processes as much as best practices (Green, Citation2006). There is a need to go beyond simplistic understandings of this evidence-practice translation to explore rich contextual links between knowledge, practical wisdom, as well as approaches to facilitate partnerships between stakeholders such as researchers, practitioners, and policy makers (Greenhalgh & Wieringa, Citation2011).

The science and practice of bridging this gap has been codified in implementation science (Eccles & Mittman, Citation2006; Kilbourne et al., Citation2020) which is concerned with fundamental questions such as – “evidence on what, for whom, in what settings and under what conditions” (Brownson et al., Citation2022, p. 5). The field offers a variety of theories and frameworks to evaluate interventions within environments for which they were designed, with a focus on uptake and transferability of evidence (Bauer et al., Citation2015). When an intervention is delivered within a complex reality, there are active and dynamic forces (Hawe et al., Citation2004) which might impede (barriers) and/or enable (facilitators) implementation outcomes (Nilsen, Citation2020). Therefore, context and implementation are deeply intertwined (Pfadenhauer et al., Citation2015). Examining contextual determinants can help: a) understand the relative importance and impact of these factors on implementation outcomes; b) identify and tailor strategies to address barriers and enhance the impact of facilitators; c) enhance our understanding of what happens in the evidence translation process; and, d) contribute to a collective understanding of expected (or unexpected) outcomes in the delivery of complex suicide prevention interventions in a real-world setting. Additionally, experiences involved in the process of delivering interventions may yield invaluable lessons. In expanding the notion of evidence, these lessons can be formal or informal reflections on what happened. If documented and consolidated systematically, these lessons can offer critical insights into important errors that can be avoided, and desirable outcomes that can be promoted.

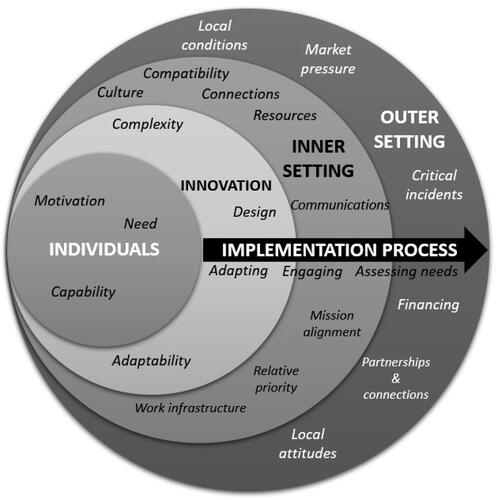

Contextual factors impinging on implementation are summarized in several determinant frameworks (Nilsen, Citation2020; Tabak et al., Citation2017). The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research is one such practical theory-based framework which offers a list of constructs associated with effective implementation. It was developed (Damschroder et al., Citation2009) as a tool for understanding what works, where and why across multiple contexts and for promoting implementation theory and was further updated in 2022 (Damschroder et al., Citation2022) based on user feedback. It consists of 5 domains: (1) the innovation domain or characteristics of the intervention; (2) the outer setting domain or the setting external to the intervention environment; (3) the inner setting domain or the intervention setting; (4) the individuals domain or the roles and characteristics of individuals involved; and (5) the implementation process domain or the activities or strategies used to implement the intervention. These domains encompass a list of constructs which can be used to understand the context, evaluate implementation progress, and explain findings.

Recently, a scoping review presented an overview of barriers and facilitators to the implementation of suicide prevention interventions, using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) (Damschroder et al., Citation2009) for classification (Kasal et al., Citation2023). However, a comprehensive understanding of the influence of a dynamic complex context on multicomponent, multilevel interventions is further needed and could help in retrospectively explaining implementation outcomes (Damschroder, Citation2020) and prospectively informing choice of strategies (Waltz et al., Citation2019).

This present paper represents an extension of our recent systematic literature review on complex suicide prevention interventions (Krishnamoorthy et al., Citation2023). The objective is to systematically map and summarize barriers, facilitators and lessons learned from reports of complex suicide prevention interventions implemented across the world using the updated CFIR (Damschroder et al., Citation2022).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This paper reports on data from a systematic review (Krishnamoorthy et al., Citation2023). The review followed the updated Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidance (Page et al., Citation2021) and was pre-registered on PROSPERO (registration number: CRD42021247950). Interventions were considered complex if they were multicomponent (three or more distinct intervention components) and multilevel (delivered across at least two levels of the social-ecology and/or levels of prevention – universal, selective, indicated) (Krishnamoorthy et al., Citation2022). Key search terms included suicid*; self harm*; AND complex intervention*, complex trial*, multilevel intervention*, multilevel trial*, multimodal intervention*, multimodal trial*, systems approach*. These key terms were searched on CINAHL, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), ProQuest, PsycINFO, PubMed, and SCOPUS for records between January 1, 1990, to December 8, 2022. The search strategy was further strengthened with a forward citation search and a thorough reference search. Detailed definitions, methods and findings from the systematic review are reported elsewhere (Krishnamoorthy et al., Citation2023).

The search yielded multiple records, which were clustered together based on shared intervention characteristics (Booth et al., Citation2013). Data regarding intervention characteristics and the use of implementation science approaches was extracted from the reports included in the study (Krishnamoorthy et al., Citation2023). Importantly, qualitative information regarding contextual details, challenges and barriers experienced during the implementation process, and enabling factors or facilitators were extracted from the reports. Reflections of authors regarding their experiences of learning and observations from implementing large scale, complex interventions were also noted. This information was not explicitly reported, usually embedded in a discussion on findings and needed to be inferred. Lessons learned as stated in the reports were summarized and analyzed.

Determinants inferred from reports were mapped using the domains, constructs and their respective definitions using the updated CFIR (Damschroder et al., Citation2022). Authors of the updated CFIR urge users to operationalize the framework based on project specific requirements. For this study, constructs were further defined as either barriers or facilitators and organized in a table ranking from most reported to the least reported (). There were some overlaps – a few barriers and facilitators identified were mapped across more than one domain. For example, community buy-in and engagement as a determinant factor could be labeled under the inner setting domain (as relational connections) and within the individuals domain (as motivation).

TABLE 1. Summary of most frequently reported barriers and facilitators across intervention clusters (in descending order of most to least frequently reported) using updated CFIR domains.

RESULTS

Data on barriers, facilitators, and lessons learned from 19 complex suicide prevention interventions was identified through 139 records (). Most complex interventions were implemented in high income countries including Australia (n = 4), Japan (n = 4), USA (n = 4), New Zealand (n = 2), Netherlands (n = 2), Canada (n = 1), and countries within Europe (n = 1). One complex intervention was implemented in India, a lower-middle-income country. Across these 19 interventions, 53 barriers and 31 facilitators were identified. These determinants were mapped onto domains represented within the updated CFIR (Damschroder et al., Citation2022). These include – the innovation domain, the outer setting domain, the inner setting domain, the individuals domain and the implementation process domain.

TABLE 2. Implementation process related information reported per intervention cluster.

Overall, the most frequently reported barriers () in delivering a complex suicide prevention intervention were related to conflicts between the research agendas and expectations and community needs, difficulties in building community ownership, and differences in cultural norms. Unexpected challenges from the outer context such as economic downturns, natural disasters, changes in policies, ongoing warfare affected implementation plans and outcomes. A key facilitator was community willingness and participation. This was also linked to an important learning related to the responsiveness of the intervention to community needs, building ownership, and embracing a pragmatic and flexible approach to implementation. Records of these interventions highlighted and emphasized the importance of reflective practice and of sustained implementation for long term impact. For some interventions barriers and/or facilitators could not be inferred, in the absence of information available in the reports.

On closer inspection, the greatest number of barriers were reported in the inner setting domain, which is defined as the setting within which the intervention is implemented (community, healthcare setting, school etc.). In some instances, there were multiple settings within which the intervention was implemented. The most common inner setting barriers were related to compatibility or challenges related to the fitness of the intervention within the setting; culture or shared values, norms, and beliefs within the setting; relational connections or challenges in maintaining relationships between different networks and teams; and resource related challenges such as – funding, knowledge, infrastructure. This was followed by the outer setting domain in which barriers related to general conditions outside of the intervention context, the pressure to compete with existing programs, and socio-cultural values and beliefs were highly reported. Barriers within the individuals domain primarily related to needs not met or addressed by the intervention, the capacity to engage in the intervention and the lack of engagement. Other barriers within the intervention domain and the implementation domain were related to innovation design and complexity, and the process of adapting and engaging recipients respectively.

Facilitators reported in these interventions were mostly related to the individuals domain. A commonly reported facilitator was motivation, followed by capability and then need. This indicates that these interventions heavily relied on stakeholder investment and engagement, not only in the delivery but also the values and ethos of the program. This was followed by facilitators within the inner setting domain which included maintaining relational connections, alignment of the intervention with inner setting goals and objectives, work infrastructure, formal and informal sharing practices, and compatibility between the setting and the intervention. Within the implementation process domain, an important facilitator was assessing the context and the needs of the recipients. Simplicity and adaptability of the intervention design were found to be other important facilitators. The only outer setting facilitators reported were related to supportive socio-cultural values and attitudes with an emphasis on bolstering community strengths and encouraging help seeking. As mentioned above, lessons learned were inferred and extracted from reports and rarely explicitly stated (). Lessons learned could be categorized along three themes – lessons related to design and evaluation, stakeholder engagement, intervention delivery and context. These themes are interrelated as lessons were found to be overlapping. For example – collaboration at the heart of intervention design, implementation, and evaluation-intervention of the people, for the people and by the people could be categorized across design, delivery, and stakeholder engagement. The most reported reflections on lessons learned were related to the design and delivery of the intervention. This theme involved reflections on procedures, overarching approach and methods/plans involved in intervention delivery. Authors of these reports consistently emphasized the importance of continuous and ongoing efforts such as training, funding support, regular contact, spaces for collaborative learning as important procedures for ensuring sustainability of intervention programs. Adaptation of the intervention and its materials was also reported as an essential procedural matter to ensure responsiveness of the intervention to recipient/beneficiary needs.

Collaboration with stakeholders and ensuring cultural sensitivity to norms and values was emphasized as an important overarching approach. In relation to lessons learned on stakeholder engagement, there was a noteworthy emphasis on community engagement and the importance of adapting to community needs. This could be done through adopting a genuine participatory and collaborative approach, delivering interventions in a culturally sensitive manner.

Importantly, reports (published and grey literature) of these interventions were not presented as implementation research or practice focused reports. Therefore, these factors or lessons learned were not formally evaluated. However, these were important experience-based observations of individuals involved in the implementation of complex suicide prevention interventions.

DISCUSSION

This review provides a glimpse into the factors influencing the delivery, adoption, and sustainment of complex suicide prevention interventions () as well as lessons learned. Similarities in barriers and facilitators reported were perhaps indicative of the universality of some challenges irrespective of settings/country contexts. For example, barriers related to resources, individual capabilities; and facilitators related to individual engagement and motivation, were found to be omnipresent. On the other hand, differences in the reporting of these determinants across settings were also found. This could be indicative of the important influence of the setting in which the complex intervention was implemented. For example, for a complex intervention implemented in a health setting – work infrastructure was reported as a barrier because of the complexities of organizational structures. Whereas work infrastructure providing stability in recruitment, training and functioning of the organization was reported as a facilitator for another intervention implemented with the Police force. Therefore, contexts are dynamic and factors that may pose as barriers to implementation in one context/setting may facilitate the intervention in another setting (May et al., Citation2016).

FIGURE 1. Barriers & facilitators to implementing complex suicide prevention interventions, mapped on updated CFIR domains.

Interventions included in this review were mostly implemented in high income countries. A few issues need to be underscored. Firstly, availability of resources (inner setting domain) and financing (outer setting domain) were not reported as the most important barriers. There may be an inherent bias as the reports included in the review were of well-resourced programs that are generally more likely to result in a publication. Under-resourced programs may not have the capacity to onboard an evaluation team, publish and thereby be represented in the data set. Complex interventions are particularly resource intensive and require a sustained source of funding. In Australia for example, a recent report outlining the current and future research priorities indicated increased funding for suicide prevention research in the context of unprecedented national policy and reform attention to suicide prevention (Reifels et al., Citation2022a). Secondly, the question of funding and resources may have been less pertinent for the countries represented in this review. However, a ground-level perspective on implementation would indicate otherwise. Hence, there could be various reasons as to why resources were not frequently reported as a barrier; an important one being – the nature of data reviewed.

Published and grey literature reports included in this review suggest that other factors such as compatibility (between the intervention and contextual needs), individual need, capability, and inner setting culture seem to pose bigger challenges. This finding seems to be consistent with the lesson highlighted in most reports, regarding the importance of ensuring responsiveness and thereby appropriateness of an intervention within a context. The finding also draws attention to the important need for adapting interventions to the needs of the beneficiaries. Recently, interest in closing the research and practice gap has brought attention to the importance of participatory approaches in implementation (Minkler et al., Citation2012). Principles such as building on strengths and resources within the community, fostering capacity building, integrating knowledge generation and implementation, and long-term commitment to sustainability, have been highlighted as important ways of facilitating a collaborative relationship in all phases of research (Kral & Kidd, Citation2018; Minkler et al., Citation2012).

The finding related to individual and organizational capability as a barrier seems to somewhat align with barriers reported for mixed interventions in suicide research in a similar scoping review (Kasal et al., Citation2023). Capacity building has been emphasized as a critical factor in bridging the gap between knowledge and its application (Brownson et al., Citation2018). Consistently reported facilitators in the study such as individual motivation and engagement also seem to be aligned with facilitators reported for mixed interventions (Kasal et al., Citation2023). However, it is difficult to make comparisons between the two studies since the types of interventions and the versions of the CFIR used to analyze determinants were different. Similar findings related to resources, capacity for implementation, and specific intervention features such as collaboration, effective planning, tailoring to context and clear implementation strategies have also been identified in literature on barriers and facilitators in healthcare (Braithwaite et al., Citation2014; Rogers et al., Citation2021). It should be mentioned that not all factors are modifiable. However, the quality of implementation depends on how these factors are mitigated.

Practice-based evidence requires a deep understanding of the challenges faced by both those who deliver and receive the intervention (Green, Citation2008). Lessons learned are an important reflection of practice-based learning that occurs in the process of delivering an intervention within real world settings. On closer examination, there were important recurrent themes in lessons learned, irrespective of the time (1990–2022) and the settings within which these interventions were implemented. There seemed to be an overwhelming emphasis on the importance of two interrelated processes – adaptation of the intervention for contextual relevance and sustained efforts in community engagement and buy in. Importantly, cultural fit of intervention approaches, engagement and buy in from communities have also been identified as factors key to sustaining tribal suicide prevention efforts (Haroz et al., Citation2021). Unless stakeholders (community members, practitioners, policy makers) see more evidence generated in circumstances like their own, they are likely to remain skeptical of the applicability and relevance of the program (Green & Nasser, Citation2017). This can be done through participatory processes and engagement of beneficiaries in specifying research questions, setting up systems, delivering programs as well as interpretation of findings (Green et al., Citation2009). Several models of engagement exist, involving strategies such as communication, partnership exchange, capacity building, leadership, and collaboration (Pinto et al., Citation2021). Despite acknowledgement of the significance of participatory approaches, “mistakes” such as prioritizing research agenda, being misinformed about the context, and lack of alignment between research objectives and context needs, continue to occur (Dearing, Citation2009, p. 22). Baumann and Cabassa (Citation2020) propose steps for adopting an “equity lens” to break away from a one size fits all approach, which may help tackle unique needs of vulnerable communities and settings (p.2).

It is noteworthy to mention that information on barriers, facilitators and/or lessons learned was unavailable for some interventions included in the review. This does not necessarily mean that a reflection on these determinants and lessons learned was non-existent. This was perhaps because reflections did not find space or articulation in the reports of these interventions and/or the trials for these interventions were ongoing. Examples of barriers, facilitators and lessons learned are not systematically recorded and/or consistently reported in suicide prevention literature. This may be because community involvement and participation (an important and recurrent theme from lessons learned) is not simply an approach, but a worldview prioritizing systemic and contextual thinking which emphasizes community involvement in every step of conducting research and delivering the intervention. This contrasts a more traditional approach to conducting research, wherein research agenda and objectivity are prioritized over community involvement and capacity building (Trickett, Citation2011). Additionally, current research endeavors do not necessarily reward generation of practice-based evidence (Ammerman et al., Citation2014). Several evidence-based practice models now exist (Pearson et al., Citation2005; Satterfield et al., Citation2009; Tucker et al., Citation2021; Upshur et al., Citation2008) which encourage the adoption of a pluralistic approach to what constitutes as evidence and has utility for practice. This is critical because decisions around implementing an intervention are not entirely based on research evidence and may involve other pragmatic considerations. However, a reciprocal relationship between evidence and practice is needed; and therefore, several sources of and methods and tools for generating practice-based evidence have also highlighted to support implementation of relevant, generalizable and effective practice (Ammerman et al., Citation2014; Green & Allegrante, Citation2020).

A scoping review has identified 17 unique frameworks in implementation science that address contextual determinants (Nilsen & Bernhardsson, Citation2019). However, Nilsen (Citation2020) also summarizes challenges in using determinant frameworks, which include difficulties in distinguishing between actual determinants (experience based) and hypothetical determinants (perceived to exist), and the lack of consensus around how context is conceptualized and defined. As discussed, the CFIR has been widely cited and continuously used (Damschroder et al., Citation2009; Skolarus et al., Citation2017). A recent revision of the framework in response to the feedback provided by CFIR users (Damschroder et al., Citation2022), demonstrates the importance of continuously responding to everyday challenges in applying theory. In suicide research, a few studies have specifically demonstrated how tailored implementation strategies can be developed using an understanding of barriers and facilitators within an intervention setting (Zbukvic et al., Citation2022). Whereas the Kasal et al. (Citation2023) study broadly summarizes the nature of barriers and facilitators reported across different types of suicide prevention interventions. Both these studies highlight the benefits of adopting such an approach in understanding what influences intervention delivery in real-life settings.

IMPLICATIONS

In this study, the CFIR was used as an organizing structure to identify and report frequencies of barriers and facilitators influencing implementation of complex suicide prevention interventions. Complexity is not simply a characteristic of the intervention itself but also a consequence of its interaction with implementation within a context (Pfadenhauer et al., Citation2017). Hence, the results reported shed light on some of these complexities involved in translating effective interventions into practice. From an implementation practice perspective, this data offers important insights into what can be expected in the translation process, what may lead interventions to succeed or fail (May et al., Citation2016). Lessons learned offer guidance into the dos and don’ts regarding delivery of complex interventions in real-life settings. This is valuable in informing future implementation efforts. From an implementation research perspective, a systematic approach to identifying barriers and facilitators can help build evidence around which determinants are relevant for suicide prevention and/or generalizable across settings (Reifels et al., Citation2022b). Furthermore, an understanding of the interplay between barriers and facilitators and the context can be further analyzed to understand what contributed to specific outcomes. Contextual influences can be unpacked by enumerating contextual effects within a study setting; determining which factors are most salient for implementation within and across settings; and applying lessons learned from other settings (Brownson et al., Citation2022).

LIMITATIONS

This study has some important limitations. The data on barriers, facilitators and lessons learned was inferred and extracted from reports of complex suicide prevention interventions and was not explicitly stated. The inclusion criteria (specifically, search terms and their respective definitions) limited the scope of our findings. Moreover, these reports were not specifically focused on implementation research or practice. The review relied on authors’ reflections on barriers, facilitators and lessons learned. Hence, data on implementation processes presented in this study is not exhaustive and does not represent the breadth of experiences involved in delivering these complex interventions.

CONCLUSIONS

The decision to implement a suicide prevention intervention suited to a setting is often guided by pragmatic considerations in addition to empirical evidence. We have presented a comprehensive summary of barriers, facilitators and lessons learned in implementation of complex suicide prevention interventions. The study highlights the importance of gathering, analyzing, and using this data to understand whether an intervention works, for whom and in what setting. There is a need to systematically understand the diverse influences on implementation outcomes, to develop a complete picture of what happens on the ground thereby enabling more informed decisions for future efforts.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

SK: conceptualization, data search, data screening, data extraction, quality appraisal, data synthesis, writing – original draft, writing – review, and editing; SM: data screening, data extraction, quality appraisal, data synthesis, writing – review, and editing; GA: supervision, writing – review, and editing; VR: supervision, writing – review and editing; JF: supervision, writing – review; LR: supervision, writing – review; KK: conceptualization, data screening, data curation, supervision, writing – review, and editing. All authors have read and agreed to this version of the manuscript.

AUTHOR NOTES

Sadhvi Krishnamoorthy, Sharna Mathieu, Victoria Ross, and Kairi Kõlves, Australian Institute for Suicide Research and Prevention, World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Research and Training in Suicide Prevention, School of Applied Psychology, Griffith University, Queensland, Australia. Gregory Armstrong, Nossal Institute for Global Health, Melbourne School of Population and Global Health, University of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. Jillian Francis, School of Health Sciences, The University of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia; Department of Health Services Research, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, Victoria, Australia; Clinical Epidemiology Program, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. Lennart Reifels, Centre for Mental Health, Melbourne School of Population and Global Health, The University of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Funding

REFERENCES

- Ammerman, A., Smith, T. W., & Calancie, L. (2014). Practice-based evidence in public health: Improving reach, relevance, and results. Annual Review of Public Health, 35(1), 47–63. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182458

- Bauer, M. S., Damschroder, L., Hagedorn, H., Smith, J., & Kilbourne, A. M. (2015). An introduction to implementation science for the non-specialist. BMC Psychology, 3(1), 32. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-015-0089-9

- Baumann, A. A., & Cabassa, L. J. (2020). Reframing implementation science to address inequities in healthcare delivery. BMC Health Services Research, 20(1), 190. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-4975-3

- Booth, A., Harris, J., Croot, E., Springett, J., Campbell, F., & Wilkins, E. (2013). Towards a methodology for cluster searching to provide conceptual and contextual “richness” for systematic reviews of complex interventions: Case study (CLUSTER). BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13(1), 118. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-13-118

- Braithwaite, J., Marks, D., & Taylor, N. (2014). Harnessing implementation science to improve care quality and patient safety: A systematic review of targeted literature. International Journal for Quality in Health Care: Journal of the International Society for Quality in Health Care, 26(3), 321–329. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzu047

- Brownson, R. C., Fielding, J. E., & Green, L. W. (2018). Building capacity for evidence-based public health: Reconciling the pulls of practice and the push of research. Annual Review of Public Health, 39(1), 27–53. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040617-014746

- Brownson, R. C., Shelton, R. C., Geng, E. H., & Glasgow, R. E. (2022). Revisiting concepts of evidence in implementation science. Implementation Science, 17(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-022-01201-y

- Damschroder, L. J. (2020). Clarity out of chaos: Use of theory in implementation research. Psychiatry Research, 283, 112461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.06.036

- Damschroder, L. J., Aron, D. C., Keith, R. E., Kirsh, S. R., Alexander, J. A., & Lowery, J. C. (2009). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-4-50

- Damschroder, L. J., Reardon, C. M., Widerquist, M. A. O., & Lowery, J. (2022). The updated consolidated framework for implementation research based on user feedback. Implementation Science, 17(1), 75. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-022-01245-0

- Dearing, J. W. (2009). Applying diffusion of innovation theory to intervention development. Research on Social Work Practice, 19(5), 503–518. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731509335569

- Eccles, M. P., & Mittman, B. S. (2006). Welcome to implementation science. Implementation Science, 1(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-1-1

- Fitzpatrick, S. J. (2018). Reshaping the ethics of suicide prevention: Responsibility, inequality and action on the social determinants of suicide. Public Health Ethics, 11(2), 179–190. https://doi.org/10.1093/phe/phx022

- Green, L. W. (2006). Public health asks of systems science: To advance our evidence-based practice, can you help us get more practice-based evidence? American Journal of Public Health, 96(3), 406–409. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2005.066035

- Green, L. W. (2008). Making research relevant: If it is an evidence-based practice, where’s the practice-based evidence? Family Practice, 25 Suppl 1(Supplement 1), i20–i24. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmn055

- Green, L. W., & Allegrante, J. P. (2020). Practice-based evidence and the need for more diverse methods and sources in epidemiology, public health and health promotion. American Journal of Health Promotion: AJHP, 34(8), 946–948. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890117120960580b

- Green, L. W., Glasgow, R. E., Atkins, D., & Stange, K. (2009). Making evidence from research more relevant, useful, and actionable in policy, program planning, and practice. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 37(6 Suppl 1), S187–S191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2009.08.017

- Greenhalgh, T., & Wieringa, S. (2011). Is it time to drop the ‘knowledge translation’ metaphor? A critical literature review. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 104(12), 501–509. https://doi.org/10.1258/jrsm.2011.110285

- Green, L. W., & Nasser, M. (2017). Furthering dissemination and implementation research: The need for more attention to external validity. In R. C. Brownson, G. A. Colditz, & E. K. Proctor (Eds.), Dissemination and implementation research in health: Translating science to practice. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190683214.003.0018

- Haroz, E. E., Wexler, L., Manson, S. M., Cwik, M., O'Keefe, V. M., Allen, J., Rasmus, S. M., Buchwald, D., & Barlow, A. (2021). Sustaining suicide prevention programs in American Indian and Alaska Native communities and Tribal health centers. Implementation Research and Practice, 2, 263348952110570. https://doi.org/10.1177/26334895211057042

- Hawe, P., Shiell, A., & Riley, T. (2004). Complex interventions: How “out of control” can a randomised controlled trial be? BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 328(7455), 1561–1563. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.328.7455.1561

- Hawton, K., & Pirkis, J. (2017). Suicide is a complex problem that requires a range of prevention initiatives and methods of evaluation. British Journal of Psychiatry: Journal of Mental Science, 210(6), 381–383. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.116.197459

- Kasal, A., Táborská, R., Juríková, L., Grabenhofer-Eggerth, A., Pichler, M., Gruber, B., Tomášková, H., & Niederkrotenthaler, T. (2023). Facilitators and barriers to implementation of suicide prevention interventions: Scoping review. Cambridge Prisms: Global Mental Health, 10, e15. https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2023.9

- Kessler, R., & Glasgow, R. E. (2011). A proposal to speed translation of healthcare research into practice. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 40(6), 637–644. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2011.02.023

- Kilbourne, A. M., Glasgow, R. E., & Chambers, D. A. (2020). What can implementation science do for you? Key success stories from the field. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 35(Suppl 2), 783–787. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06174-6

- Kral, M. J., & Kidd, S. (2018). Community-based participatory research and community empowerment for suicide prevention. In J. K. Hirsch, E. C. Chang, & J. Kelliher Rabon (Eds.), A positive psychological approach to suicide: Theory, research, and prevention (pp. 285–299). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-03225-8_12

- Krishnamoorthy, S., Mathieu, S., Armstrong, G., Ross, V., Francis, J., Reifels, L., & Kõlves, K. (2023). Utilisation and application of implementation science in complex suicide prevention interventions: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 330, 57–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2023.02.140

- Krishnamoorthy, S., Mathieu, S., Ross, V., Armstrong, G., & Kõlves, K. (2022). What are complex interventions in suicide research? Definitions, challenges, opportunities, and the way forward. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(14), 8591. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19148591

- May, C. R., Johnson, M., & Finch, T. (2016). Implementation, context and complexity. Implementation Science, 11(1), 141. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0506-3

- Minkler, M., Salvatore, A. L., & Chang, C. (2012). Participatory approaches for study design and analysis in dissemination and implementation research. In R. C. Brownson, G. A. Colditz, & E. K. Proctor (Eds.), Dissemination and implementation research in health translating science to practice. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:Oso/9780199751877.001.0001

- Nilsen, P. (2020). Overview of theories, models and frameworks in implementation science. In P. Nilsen & S. Birken (Eds.), Handbook on implementation science (pp. 8–31). Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781788975995.00008

- Nilsen, P., & Bernhardsson, S. (2019). Context matters in implementation science: A scoping review of determinant frameworks that describe contextual determinants for implementation outcomes. BMC Health Services Research, 19(1), 189. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4015-3

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., & Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 372, n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

- Pearson, A., Wiechula, R., Court, A., & Lockwood, C. (2005). The JBI model of evidence-based healthcare. JBI Evidence Implementation, 3(8), 207.

- Pfadenhauer, L. M., Gerhardus, A., Mozygemba, K., Lysdahl, K. B., Booth, A., Hofmann, B., Wahlster, P., Polus, S., Burns, J., Brereton, L., & Rehfuess, E. (2017). Making sense of complexity in context and implementation: The context and implementation of complex interventions (CICI) framework. Implementation Science, 12(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0552-5

- Pfadenhauer, L. M., Mozygemba, K., Gerhardus, A., Hofmann, B., Booth, A., Lysdahl, K. B., Tummers, M., Burns, J., & Rehfuess, E. A. (2015). Context and implementation: A concept analysis towards conceptual maturity. Zeitschrift Fur Evidenz, Fortbildung Und Qualitat im Gesundheitswesen, 109(2), 103–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.zefq.2015.01.004

- Pinto, R. M., Park, S., Miles, R., & Ong, P. N. (2021). Community engagement in dissemination and implementation models: A narrative review. Implementation Research and Practice, 2, 2633489520985305. https://doi.org/10.1177/2633489520985305

- Platt, S., & Niederkrotenthaler, T. (2020). Suicide prevention programs: Evidence base and best practice. Crisis, 41(Supplement 1), S99–S124. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000671

- Presseau, J., McCleary, N., Lorencatto, F., Patey, A. M., Grimshaw, J. M., & Francis, J. J. (2019). Action, actor, context, target, time (AACTT): A framework for specifying behaviour. Implementation Science, 14(1), 102. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-019-0951-x

- Reifels, L., Krishnamoorthy, S., Kõlves, K., & Francis, J. (2022b). Implementation science in suicide prevention. Crisis, 43(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000846

- Reifels, L., Krysinska, K., Andriessen, K., Ftanou, M., Machlin, A., McKay, S., Robinson, J., Pirkis, J. (2022a). Suicide prevention research priorities: Final report. The University of Melbourne and Suicide Prevention Australia. https://www.suicidepreventionaust.org/research-grants/research-outcomes/

- Rogers, H. L., Pablo Hernando, S., Núñez-Fernández, S., Sanchez, A., Martos, C., Moreno, M., & Grandes, G. (2021). Barriers and facilitators in the implementation of an evidence-based health promotion intervention in a primary care setting: A qualitative study. Journal of Health Organization and Management, ahead-of-print(ahead-of-print), 349–367. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHOM-12-2020-0512

- Satterfield, J. M., Spring, B., Brownson, R. C., Mullen, E. J., Newhouse, R. P., Walker, B. B., & Whitlock, E. P. (2009). Toward a transdisciplinary model of evidence-based practice. Milbank Quarterly, 87(2), 368–390. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00561.x

- Skivington, K., Matthews, L., Simpson, S. A., Craig, P., Baird, J., Blazeby, J. M., Boyd, K. A., Craig, N., French, D. P., McIntosh, E., Petticrew, M., Rycroft-Malone, J., White, M., & Moore, L. (2021). A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: Update of Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 374, n2061. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n2061

- Skolarus, T. A., Lehmann, T., Tabak, R. G., Harris, J., Lecy, J., & Sales, A. E. (2017). Assessing citation networks for dissemination and implementation research frameworks. Implementation Science, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0628-2

- Tabak, R. G., Chambers, D. A., Hook, M., & Brownson, R. C. (2017). The conceptual basis for dissemination and implementation research. In R. C. Brownson, G. A. Colditz, & E. K. Proctor (Eds.), Dissemination and implementation research in health: Translating science to practice (pp. 31). Oxford University Press.

- Trickett, E. J. (2011). Community-based participatory research as worldview or instrumental strategy: Is it lost in translation(al) research? American Journal of Public Health, 101(8), 1353–1355. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300124

- Tucker, S., McNett, M., Mazurek Melnyk, B., Hanrahan, K., Hunter, S. C., Kim, B., Cullen, L., & Kitson, A. (2021). Implementation science: Application of evidence-based practice models to improve healthcare quality. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 18(2), 76–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/wvn.12495

- Upshur, R. E. G., VanDenKerkhof, E. G., & Goel, V. (2008). Meaning and measurement: An inclusive model of evidence in health care. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 7(2), 91–96. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2753.2001.00279.x

- Waltz, T. J., Powell, B. J., Fernández, M. E., Abadie, B., & Damschroder, L. J. (2019). Choosing implementation strategies to address contextual barriers: Diversity in recommendations and future directions. Implementation Science, 14(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-019-0892-4

- Westefeld, J. S. (2020). Suicide prevention: An issue of social justice. Journal of Prevention and Health Promotion, 1(1), 58–79. https://doi.org/10.1177/2632077020946419

- Wilkins, N., Thigpen, S., Lockman, J., Mackin, J., Madden, M., Perkins, T., Schut, J., Van Regenmorter, C., Williams, L., & Donovan, J. (2013). Putting program evaluation to work: A framework for creating actionable knowledge for suicide prevention practice. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 3(2), 149–161. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13142-012-0175-y

- Yip, P. S. F., Tang, L. (2021). Public health approach to suicide research. In K. Kõlves, M. Sisask, P. Värnik, A. Värnik, & D. D. Leo (Eds.), Advancing suicide research. Hogrefe Publishing. http://public.eblib.com/choice/PublicFullRecord.aspx?p=6454541

- Zalsman, G., Hawton, K., Wasserman, D., van Heeringen, K., Arensman, E., Sarchiapone, M., Carli, V., Höschl, C., Barzilay, R., Balazs, J., Purebl, G., Kahn, J. P., Sáiz, P. A., Lipsicas, C. B., Bobes, J., Cozman, D., Hegerl, U., & Zohar, J. (2016). Suicide prevention strategies revisited: 10-year systematic review. Lancet. Psychiatry, 3(7), 646–659. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30030-X

- Zbukvic, I., Rheinberger, D., Rosebrock, H., Lim, J., McGillivray, L., Mok, K., Stamate, E., McGill, K., Shand, F., & Moullin, J. C. (2022). Developing a tailored implementation action plan for a suicide prevention clinical intervention in an Australian mental health service: A qualitative study using the EPIS framework. Implementation Research and Practice, 3, 26334895211065786. https://doi.org/10.1177/26334895211065786