Abstract

Background: Adolescents often have emotional and behavioural problems that general practitioners are likely to miss. While nearly 80% of them consult their GP every year, it is usually for physical, not psychological reasons. Trust in their GPs in necessary for screening.

Objectives: To identify the key quality desired by adolescents for them to feel free to confide in GPs. To determine whether this quality differed according to gender, level of at-risk behaviours or interlocutor: friend, parent or GP.

Methods: A descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted in 182 French educational institutions chosen by lot. Fifteen-year-olds completed a self-administered questionnaire under examination conditions. While the questions on behaviour were drawn from the cross-national survey entitled ‘Health behaviour in school-aged children (HBSC),’ the questions on conditions conducive to trust were drawn from previous studies.

Results: A total of 1817 (911 boys, 906 girls) questionnaires were analysed. Adolescents said they seldom confided. The main quality they expected from a GP to whom they could confide in was ‘honesty’, which meant ensuring secrecy, refraining from judgment, and putting forward the right questions. This priority was modified by neither gender nor experience with health-risk behaviour. The quality of ‘reliability’ was more closely associated with their parents or friends, while ‘emotionality’ was cited less often.

Conclusion: To gain the trust of adolescents, GPs have to be sincere and non-manipulative and have the ability to ensure confidentiality and to put forward the right questions without passing judgment. Can this be verified during consultations? Prospective studies could shed light on this point.

Above all, troubled adolescents expect from their GP ‘honesty’, which meant secrecy, to refrain from judgment and to put forward the right questions.

High-risk girls were the most inclined to talk to their GP about interpersonal problems but they were reluctant to talk about their bodies.

Introduction

Adolescence is a period marked by biological, psychological and social turbulence, which can be manifested by health-risk behaviour,[Citation1] self-harm, aggressiveness, use and misuse of alcohol, drugs and sexual behaviour, etc. These behaviours increase short-term morbimortality and long-term adult morbimortality.[Citation1,Citation2] General practitioners (GP) are ideally placed to address these issues opportunistically.[Citation3,Citation4] However, despite the high prevalence of mental disorders in young people, detection and treatment are low.[Citation5]

Adolescents, particularly the most troubled, seldom request professional help; instead, they are inclined to turn to their friends or parents.[Citation3] Even if consultations are essentially physical or administrative, and only 8% psychological,[Citation6] 80% of adolescents see their GP at least once a year.[Citation3] Moreover, organized preventive visits are generally few and far between.[Citation7] Occasional consultation represents the more relevant opportunity for GPs to address the unspoken difficulties not included in the adolescent’s stated reasons for a visit.[Citation8] To avoid allegations of intrusiveness and so as to facilitate its leading to an expression or request, this approach necessitates a trusting relationship.[Citation9]

When examining the expectations for GPs expressed by adolescents,[Citation10] it is possible to rank them in order.

The first objective was to identify the key quality desired by adolescents for them to feel free to confide in GPs. Our second objective was to determine whether this quality differed according to gender, level of at-risk behaviours or interlocutor: friend, parent or GP.

Methods

Sample and survey design

In June 2012, we carried out a cross-sectional survey involving a representative sample of 15-year-old adolescents enrolled in 182 randomly drawn schools in two French regions, which taken together represent 5.5% of the overall French population. Nominative selection was performed by the statistical services of the French education ministry. Adolescents and their parents were informed before the study in a letter presenting the survey and asking for their consent to participate. At the beginning of the questionnaire, adolescents were offered a second opportunity to decline to participate. As is obligatorily the case in France when surveys are conducted in a school setting, the competent authorities in the French Ministry of Education preliminarily approved the study. By French legislation on observational studies, our survey was registered by the National Commission on Informatics and Liberty (CNIL no. 1560423 and no. 7z70310939s), which is mandated to ensure personal data protection and prohibits any search for ethnic differences.

At school, participants were asked to fill out with pen and ink a self-completion paper-based questionnaire under examination conditions in the presence of a representative of the health arm of the French Ministry of Education. Data were processed by an electronic recording device or captured manually by two independent operators.

The questionnaire

Development of the questionnaire necessitated preliminary studies. It was drawn up by a non-formalized expert consensus associating a GP, a child psychiatrist, a biostatistician, a school physician, a public health physician.

There were three series of questions:

Interrogation on the interlocutor chosen according to the difficulty encountered: ‘When you have (or had) difficulty involving ….’ You spoke (or would speak) about it to…’ Difficulties were grouped under three headings:

difficulties in physical health and worry over not being ‘normal‘;

personal difficulties involving: stress, morale, assaults suffered, aggressiveness, time in front of screens and consumption of illegal drugs;

interpersonal difficulties concerning parents, teachers, friends, boy/girlfriends.

Interrogation on conditions for trust. As we did not find in the literature a questionnaire specifically addressed to adolescents, we based ours on the Wake Forest University Scale (WFUS) adapted to adults and the children’s interpersonal trust belief scale (CITB) adapted to children averaging 10 years of age.[Citation11]

The CITB presents different situations experienced by a child who is then asked to position himself with regard to three types of qualities expected from an adult: ‘reliability‘ = being constant and consistent; ‘emotionality’ = not causing emotional harm; ‘honesty’ = being kind, sincere and non-manipulative. In our survey, situations were replaced by questions drawn from the WFUS that respected the CITB categories and presented formulations adapted to adolescents. Adolescents were asked to justify the reasons for their trust according to its addressee and to each of the three following categories:

If you speak to … (parent/friend/GP), it is because:

‘He/she has already assisted or supported you’, ‘he/she is available to hear you out.’ ‘You understand what he says’ (= ‘reliability’).

‘You feel understood.’ ‘He/she knows how to put you at ease’, ‘you’re not afraid of disappointing him’ (= ’emotionality’)

‘He/she knows how to ask you the right questions’, ‘he/she keeps the confided secrets’, ‘you don’t feel you’re being judged’ (= ‘honesty’).

Interrogation on health-risk behaviour. For this part, we had access by convention to formulations of the ‘Health behaviour in school-aged children’ international questionnaire (HBSC).[Citation12] We chose questions that were related to health-risk behaviour:[Citation1,Citation13] tobacco, alcohol and cannabis consumption, early sexual intercourse, group violence (brawls) and attempted suicide. Questions on firearms and automobile driving were excluded because they corresponded neither to the ages nor the French context.

The questionnaire was tested during three preliminary consecutive studies. The first one assessed 15 and 16-year-old adolescents seen by GPs and concerned the levels of relevance and comprehension of questions. After some improvements, the second one included 115 students of 15 and 16 years old in a school setting. The non-response rate was 28% for questions about the most sensitive or intimate matters. Then, the third questionnaire had his presentation simplified, but the questions were the same. This questionnaire presented a non-response rate lower than 5%.[Citation14]

Statistical analysis

We divided them into three subgroups. The ‘low risk’ group (LR) brought together those stating they had never engaged in any of the at-risk behaviours. The ‘high risk’ (HR) group was composed of those stated that they had engaged in at least one of the behaviours reaching the previously described level of severity. Finally, the ‘moderate risk’ group (MR) consisted in those belong to neither of these two groups.

HR presented at least one behaviour with a level of severity that was worrisome due to repetition or early occurrence, e.g. smokes at least one cigarette every day; has consumed so much alcohol as to become completely inebriated at least four times in his life; has smoked at least three joints over the last 30 days; had sexual intercourse at least one time by or before the age of 13; has participated in a physical fight at least three times over the last 12 months; has made at least two suicide attempts in his life.

We decided ‘at least two’ because the reporting rate for ‘one’ (20%) was pronouncedly higher than in studies,[Citation15] and that suicide attempts could be confused with other forms of self-harm.

While members of the LR had presented none of the above behaviours, the MR brought together all the other adolescents. Comparison between the three groups, which were constituted according to declared health-risk behaviours, was carried out using the χ2 test with a 5% risk of error under the null hypothesis of homogeneity of proportions between the groups. SAS software version 9.3 was employed.

Results

Out of the 192 schools contacted, 182 participated; 2,158 students were registered. A total of 1,819 questionnaires were collected from 911 girls and 906 boys. The overall loss represented 15.8%. Distribution according to health-risk behaviours is detailed in .

Table 1. Behaviours of the adolescents according to gender and health risk group.

Most of the adolescents had seen their GPs over the previous year: from 95% of the girls in LR group to 86% of the boys in the LR and HR groups. Those who consulted frequently (>5/year) were significantly more numerous in the HR group, among both boys (28%, P = 0.026) and girls (32%, P < 0.001).

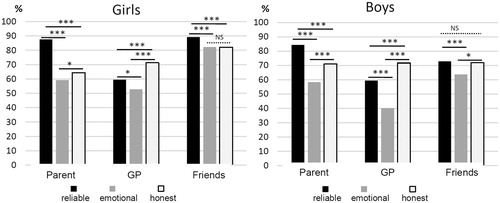

The adolescents preferred to confide in their parents and friends (). It was without preference for any single topic that they spoke to their parents about all their concerns. To their GPs, they focused on their physical health, were reluctant to talk about their at-risk behaviours and said nothing about their relationships. With their friends, they were less inclined to mention their physical concerns. Distribution was similar for the two sexes except for confiding in friends, which occurred more frequently in girls.

Figure 1. Nature of the difficulties or concerns voiced by the teenagers according to gender and type of interlocutor.

By selecting their behaviours (), the HR adolescents confided less than the others in their parents, except for girls, who confided as much in them as did members of the other groups about their interpersonal difficulties.

Table 2. Nature of the difficulties or concerns mentioned by the adolescents according to interlocutor, risk group and gender.

HR girls spoke less to their GP about their physical health and talked more to them about their relationships. Regardless of their groups, boys spoke more to their GPs, while girls opened up to their friends.

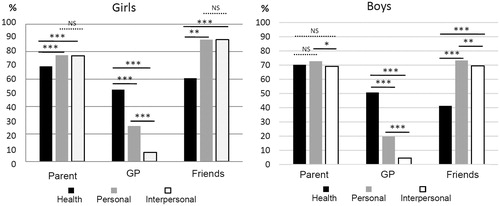

All told, 39% (n = 712) of the adolescents confided in their GPs, from whom they expected first ‘honesty’, and then ‘reliability’ and ‘emotionality’. From their parents or friends, they placed ‘reliability’ before ‘honesty’. In all cases, the quality of ‘emotionality’ was cited the least often ().

Table 3. Classification of the qualities expected by adolescents who say they confide in their physicians according to gender, risk group and interlocutor.

For the adolescents who said they confided in GPs (), the qualities they expected from them did not differ according to the level of their health-risk conduct. As concerns parents, ‘reliability’ was less frequently expected by HR adolescents, and there was no difference pertaining to the other qualities.

Discussion

Main findings

The main quality the 15-year-olds expected from GPs so that they would confide in them about their difficulties was ‘honesty’, which meant that their GP ensured secrecy, refrained from judgment, and put forward the right questions without difference of gender or health-risk conducts.

HR girls were the most inclined to talk to their GP about interpersonal problems but were reluctant to talk about their bodies. This aspect has not been found in medical literature and it deserves an exploration.

Limitations of methods

The first limit was that the one and only age of the adolescents, 15 years, reduced the interest of the study for other ages. However, our choice enabled us to obtain a homogeneous sample at an age where the rate of at-risk behaviours steeply increases,[Citation16] and it may not be too late for effective preventive action. Moreover, 15-year-olds currently represent the most widely studied age bracket in Europe.[Citation15]

The second limit concerns the French national health system. Access to doctors is very easy and open and not limited according to financial resources. This French specificity leads us to question the reproducibility of the results in other countries.

The third limit involved the data collection conditions, which while highly conducive to the expression of opinions, were not based on observations drawn from a concrete context. In fact, priority was given to emancipation from the influence exerted by an adult, and that is one reason why the questionnaire was filled out under conditions favouring anonymity and sincere responses.

The fourth limit involved the choice of health-risk behaviours, in which we subscribed to present-day orientations of the literature associating internalized and externalized disorders.[Citation13,Citation17] The choices of frequency and early age as criteria of severity allowed us to avoid focusing on initial trials (alcohol, cannabis) or impulsive-reactive behaviour. Severity from one cigarette a day is well-referenced at that age,[Citation18] particularly in its relationships with stress and suicide.[Citation19] The decision to ask about more than one suicide attempt was motivated by a wish to emphasize repetition, which is an important severity criterion in the literature. The very high rate for one attempt by girls (21%) was more elevated than those reported in all the international or national studies[Citation15,Citation20,Citation21] and suggested that self-harm gestures were being improperly considered as suicide attempts. Moreover, it has been shown that severity is preferentially associated with repetition.[Citation22]

We did not analyse if GP’s gender has an impact on adolescent’s expectations. It could be studied in a more specific study.

Our results are reliable thanks to the number of schools and students included.

Confidence, a complex notion

We tried to establish a hierarchy of different criteria for adolescents’ trust in GPs. It nonetheless bears mentioning that trust is a highly complex notion representing an aggregation of possibly overlapping criteria. Moreover, it is quite possible that adolescents are far from homogeneous in the ways they appropriate the concept of trust.

Comparison to the literature

This study confirmed several well-known factual elements reported in the literature: adolescents with psychological problems confide first in their friends and then in their parents, but in our study, they do it more, and with less variance.[Citation23]

When they address themselves to GPs, it is essentially due to their physical health problems.[Citation2,Citation24] Their reluctance to confide in GPs about their psychological and interpersonal problems is equally well known.[Citation9,Citation23] Our study showed that even if their reasons for seeing their GP were mainly somatic, at-risk adolescents were the ones who consulted most frequently. However, HR girls talked to their GPs about their interpersonal problems; paradoxically, they were less inclined to confide in their GPs about their bodies. This disinclination carried over to their parents, but not to their friends. It would seem that the at-risk girls were reluctant to talk to an adult about their bodies and that GP’s function in no way modified their wariness.

For girls, friends remained the primary confidants. The differences we found in attitudes to calling for assistance is in agreement with several studies in which boys are described as generally less likely to seek out help from adults.[Citation25] Our study allows this observation to be nuanced; unlike other boys, those in difficulty confide less in their parents, as much to GPs, and more to friends.

In fact, it was according to their interlocutors that adolescents effectively defined the qualities required for trust. The quality expected from parents was ‘reliability’ = ‘he has already helped me, he is available, he understands what I say.’ The quality expected from GPs was ‘honesty’, which corresponded to the following three wishes:

The first wish was for confidentiality, confirmed by several studies.[Citation3,Citation10,Citation26] Without assurances of secrecy, adolescents will close themselves off and refrain from addressing sensitive topics such as health-risk behaviours.[Citation26] The determination to respect confidentiality has to be reasserted during consultation with adolescents.

The second wish, confirmed by other studies,[Citation9,Citation10] is not to be judged. It is particularly necessary when interacting with adolescents.

The third wish, which is that the GP ‘put forward the right questions’, has seldom been mentioned in the literature. As adolescents have trouble finding the words allowing them to speak of themselves, they express their difficulties using somatic complaints.[Citation20] While in the final analysis they are not opposed to speaking of themselves, they expect the initiative to come from an adult.

What are ‘the right questions’? Several tools have been validated and recommended in France; some can be memorized, such as the test to screen suicide risks and the HEADSS psychosocial interview guide;[Citation17] others such as the ADRSp are self-administered questionnaires designed to evaluate depressive tendencies.[Citation27–29]

Conclusion

Several qualities are required to gain the trust of adolescents. Our study has highlighted those that appear primordial for all adolescents, regardless of their gender or behaviour; the most important is ‘honesty’ understood as being kind, sincere and non-manipulative and the ability to ensure confidentiality and to put forward the right questions without passing judgment.

The second quality expected is ‘reliability’ and the third is ‘emotionality’.

The girls in the high-risk group confide more to the other persons mentioned than to GPs. It would be relevant to explore how GPs could convince them to open up.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the proprietors of the merged data bases: ORS Alsace and the biostatistics and epidemiology unit INSERM CIC 0802 of Poitiers as well as their partners: the HBSC France association, the Poitiers rectorate, the Relais 17 association, ORS Poitou-Charentes, ARS Poitou-Charentes, the medicine and pharmacy faculty of the University of Poitiers, the Strasbourg rectorate, ARS Alsace, DRJSCS Alsace, the city of Strasbourg, the city of Mulhouse and the Bas-Rhin departmental council.

The authors also wish to thank Brigitte Drapt, Joelle Chevalier and Coralie Servant for their active participation.

Ethics

I declare to be the author of this article and have complied with the ethical rules in force in France: The study was conducted by the regulations applied in France, a country in which committees for the protection of persons do not examine observational research. The Helsinki declaration principles have been respected: informed consent and the guarantee of confidentiality using anonymity.

In accordance with French legislation on observational studies, our survey was registered by the National Commission on Informatics and Liberty (CNIL no. 1560423 and no. 7z70310939s), which is mandated to ensure personal data protection.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Gore FM, Bloem PJN, Patton GC, et al. Global burden of disease in young people aged 10–24 years: A systematic analysis. Lancet 2011;377:2093–102.

- Colman I, Murray J, Abbott RA, et al. Outcomes of conduct problems in adolescence: 40-year follow-up of national cohort. Br Med J. 2009;338:a2981.

- Tylee A, Haller DM, Graham T, et al. Youth-friendly primary-care services: How are we doing and what more needs to be done? Lancet 2007;369:1565–1573.

- Bates T, Illback RJ, Scanlan F, et al. Somewhere to turn to, someone to talk to [Internet]. Dublin: Headstrong – The National Centre for Youth Mental Health; 2009 [cited 2016 Mar 17]. Available from: http://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/11947/1/Headstrong_somewhere_to_turn.pdf.

- Roberts J, Crosland A, Fulton J. Patterns of engagement between GPs and adolescents presenting with psychological difficulties: A qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2014;64:e246–254.

- Meynard A, Broers B, Lefebvre D, et al. Reasons for encounter in young people consulting a family doctor in the French speaking part of Switzerland: A cross sectional study. BMC Fam Pract. 2015;16:159.

- Nordin JD, Solberg LI, Parker ED. Adolescent primary care visit patterns. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8:511–516.

- Binder P, Caron C, Jouhet V, et al. Adolescents consulting a GP accompanied by a third party: Comparative analysis of representations and how they evolve through consultation. Fam Pract. 2010;27:556–562.

- Leavey G, Rothi D, Paul R. Trust, autonomy and relationships: The help-seeking preferences of young people in secondary level schools in London (UK). J Adolesc. 2011;34:685–693.

- Freake H, Barley V, Kent G. Adolescents’ views of helping professionals: A review of the literature. J Adolesc. 2007;30:639–653.

- Hall MA, Zheng B, Dugan E, et al. Measuring patients’ trust in their primary care providers. Med Care Res Rev. 2002;59:293–318.

- Roberts C, Freeman J, Samdal O, et al. The health behaviour in school-aged children (HBSC) study: Methodological developments and current tensions. Int J Public Health. 2009;54(Suppl 2):140–150.

- Brener ND, Kann L, Shanklin S, et al. Methodology of the youth risk behavior surveillance system—2013. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2013;62:1–23.

- Esnault-Prunier M-L. What are the adolescents conditions for them to confide in someone close to them including their GP?: Creation and validation of a questionnaire for 15 years old students [dissertation]. Poitiers: Université de Poitiers; 2011.

- Kokkevi A, Rotsika V, Arapaki A, et al. Adolescents’ self-reported suicide attempts, self-harm thoughts and their correlates across 17 European countries. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2012;53:381–389.

- Chan Chee C, Jezewski Serra D. Hospitalizations for suicide attempts between 2004 and 2007 in metropolitan France. PMSI-MCO analysis. Special issue. Suicide and suicide attempts: Situation in France. Bull Epidemiol Hebd. (Paris) 2011;492–496.

- Goldenring J, Rosen D. Getting into adolescent heads: An essential update. Contemp Pediatr-Montvale 2004;21:64–92.

- Riala K, Taanila A, Hakko H, et al. Longitudinal smoking habits as risk factors for early-onset and repetitive suicide attempts: The Northern Finland 1966 birth cohort study. Ann Epidemiol. 2009;19:329–335.

- Stanley IH, Snyder D, Westen S, et al. Self-reported recent life stressors and risk of suicide in pediatric emergency department patients. Clin Pediatr Emerg Med. 2013;14:35–40.

- Youssef NN, Atienza K, Langseder AL, et al. Chronic abdominal pain and depressive symptoms: Analysis of the national longitudinal study of adolescent health. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:329–32.

- Jousselme C, Cosquer M, Hassler C. Adolescents portraits. Epidemiological multicentric study in schools in 2013. Paris, France: INSERM; 2015.

- Christiansen E, Jensen BF. Risk of repetition of suicide attempt, suicide or all deaths after an episode of attempted suicide: A register-based survival analysis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2007;41:257–265.

- Mauerhofer A, Berchtold A, Michaud P-A, et al. GPs’ role in the detection of psychological problems of young people: A population-based study. Br J Gen Pract. 2009;59:e308–314.

- du Roscoät E, Beck F. Efficient interventions on suicide prevention: A literature review. Rev Dépidémiologie Santé Publique. 2013;61:363–374.

- Cotton SM, Wright A, Harris MG, et al. Influence of gender on mental health literacy in young Australians. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2006;40:790–796.

- Ford CA, Millstein SG, Halpern-Felsher BL, et al. Influence of physician confidentiality assurances on adolescents’ willingness to disclose information and seek future health care. A randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Assoc. 1997;278:1029–1034.

- Haute Autorité de Santé. Adolescents manifestations of depression. Screening, diagnosis and strategy of care in primary care. Paris, France: HAS; 2014.

- Binder P, Chabaud F. To detect teenagers’ suicide behaviour (II). Clinical audit among 40 general practitioners. Rev Prat. 2007;57:1193–1199.

- Binder P, Heintz A-L, Servant C, et al. Screening for adolescent suicidality in primary care: The bullying-insomnia-tobacco-stress test. A population-based pilot study. Early Interv Psychiatry 2016; doi: 10.1111/eip.12352 (Epub ahead of print).