Abstract

Background: The gut feelings questionnaire (GFQ) is the only tool developed to assess the presence of a ‘sense of alarm’ or a ‘sense of reassurance’ in the diagnostic process of general practitioners (GPs). It was created in Dutch and English and has validated versions in French, German and Polish.

Objectives: To obtain a cross-cultural translation of the GFQ into Spanish and Catalan and to assess the structural properties of the translated versions.

Methods: A six-step procedure including forward and backward translations, consensus, and cultural and linguistic validation was performed for both languages. Internal consistency, factor structure, and content validity were assessed.

Results: Internal consistency was high for both questionnaires (Cronbach’s alpha for GFQ-Spa = 0.94 and GFQ-Cat = 0.95). The principal component analysis identified one factor with the sense of alarm and the sense of reassurance as two opposites, explaining 76% of the total variance for the GFQ-Spa, and 77% for the GFQ-Cat.

Conclusion: Spanish and Catalan versions of the GFQ were obtained. Both have been cross-culturally adapted and showed good structural properties.

KEY MESSAGES

The gut feelings questionnaire (GFQ) is the only tool developed to assess objectively the presence of a sense of alarm or a sense of reassurance in GP consultations.

The GFQ was cross-culturally translated and validated into Spanish and Catalan.

The GFQ is now available for research among Spanish and Catalan-speaking doctors.

Introduction

The role of gut feelings in the general practitioner’s (GPs) decision-making process has been described in several qualitative studies from the Netherlands, Belgium, France, and Spain [Citation1–3]. These studies have shown that gut feelings play a substantial role in diagnostic reasoning and that many general practitioners in Europe trust and follow them. GPs distinguish two types of gut feelings, both with prognostic implications. The ‘sense of alarm’ is defined as ‘an uneasy feeling perceived by a GP as he/she is concerned about a possible adverse outcome, even though specific indications are lacking.’ The ‘sense of reassurance’ is defined as ‘a secure feeling perceived by a GP about the further management and course of a patient's problem, even though he/she may not be certain about the diagnosis [Citation1].’

GPs in the studies mentioned above showed interest in knowing the accuracy of their gut feelings. The gut feelings questionnaire (GFQ) was created and validated to facilitate quantitative research into the role of gut feelings and their diagnostic value [Citation4]. The latest version can be found in the COGITA website (http://www.gutfeelings.eu/questionnaire/). The COGITA expert group is a European network for collaborative research on gut feelings in general practice. French, Polish and German versions of the GFQ have already been linguistically validated. They are also available at the COGITA website. Our objective was to obtain a cross-cultural translation of the GFQ into Spanish and Catalan and to assess the structural properties of the translated versions.

Methods

Cross-cultural validation procedure

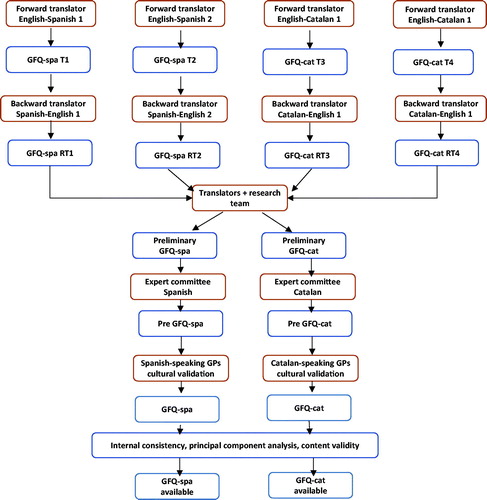

We followed the standard criteria for linguistic validation found in previous literature and the adapted procedural scheme used in previous validations of the modified GFQ [Citation5,Citation6]. A linguistic validation procedure was performed in Majorca (Spain) from September 2016 to January 2017. summarizes the validation procedure of the GFQ.

First step: forward translation. Two independent forward translations into Spanish of the modified GFQ questionnaire (T1, T2) were produced by two bilingual doctors whose mother tongue was Spanish. Two bilingual family doctors whose mother tongue was Catalan, produced two independent versions of the GFQ in Catalan (T3, T4).

Second step: backward translation. Four family doctors whose mother tongue was English, two of them with Spanish and two with Catalan as second languages, produced backward translations of the T1, T2, T3, and T4 versions into English. The results were two backward translations into Spanish (RT1, RT2), and two into Catalan (RT3, RT4).

Third step: synthesis and expert committee. The translators and the research team conducted a synthesis of the translations. The results were preliminary Spanish and Catalan versions of the GFQ. Two expert panels were formed, one for each language. Each panel was composed of members of the research team (BO, SM, ME), the two forward translators, the two backward translators of each version, and a linguistic expert. The expert panels reviewed all versions and the synthesis of each language and reached agreements on discrepancies. The items were reviewed for clarity, semantic, idiomatic, experiential, and conceptual equivalences. The panel agreed a pre-final translation of the Spanish (GFQ-Spa) and Catalan (GFQ-Cat) GFQ based on the adequacy of each item and the expected comprehension of the phrasing of the item.

Fourth step: cultural validation. The GFQ-Spa was sent to 18 Spanish speakers GPs, nine from different Spanish regions and nine from eight Latin American Spanish-speaking countries. The GFQ-Cat was sent to eight Catalan speakers GPs from the Balearic Islands and Catalonia. A letter explaining the gut feelings concept and the purpose of the questionnaire was also sent to all the GPs. They were asked to indicate the comprehension of the items, possible misunderstandings, or any lack of clarity in the statements.

Fifth step: final consensus. After studying the answers, the research team developed the final version of the GFQ-Spa and the GFQ-Cat.

Sixth step: submission to developers. The final versions of both translations were presented and assessed by the original developers of the GFQ in a meeting of the COGITA group [Citation7].

The study was approved by the Majorca Primary Health Care Research Committee and by the Regional Ethical Committee.

Structural properties

We purposively selected 15 GPs to fill out the GFQ-Spa and eight GPs to fill out the GFQ-Cat for one working day. Patients with new reasons for encounter were included. We obtained 150 consultations with the GFQ-Spa fulfilled and 79 with the GFQ-Cat. Internal consistency was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha test. Principal component analysis (PCA) was used to explore the factor structure of the GFQ.

No Delphi procedure

The focus group study conducted with Spanish and Catalan speaking GPs showed the same GF content among GPs in Spain as the original Dutch study [Citation3,Citation8]. Delphi procedures performed in the Netherlands and France also gave comparable outcomes [Citation1,Citation2]. Moreover, the feasibility studies of the GFQ in France, Belgium, and the Netherlands did not show differences between GPs from different countries (pending publication). We can assume that the gut feelings concept is a cross-border concept. We agreed with the developers of the original GFQ not to repeat the Delphi consensus procedure in Spain.

Results

Cross-cultural translation

The Spanish term chosen for gut feelings was corazonada. It is defined by the Diccionario de Uso del Español (2aEd) as a ‘vague belief that something happy or unhappy is going to happen.’ The Catalan term was pressentiment. It is defined by the Gran diccionari de la llengua Catalana (1aEd) as the ‘impression or conviction that something is going to happen’.

There were no major difficulties in either translation. The word outcome (questions 4 and 5) was translated into Spanish using desenlace (which has a literary sense) and into Catalan using resultat (more factual sense). In both languages, an impersonal construction was chosen to avoid leaving the subject (Yo in Spanish, Jo in Catalan) alone at the end of the first sentence in question 9. The English expression ‘wait and see’ can be literally translated into Spanish as espera y verás, and into Catalan as espera i veuràs. The expert panel agreed to include the expressions actitud expectante in Spanish and actitut expectant in Catalan as they are equivalent medical expressions among Spanish and Latin American doctors to the English ‘wait and see’.

The validated versions of the GFQ into Spanish and Catalan (GFQ-Spa and GFQ-Cat) can be consulted and downloaded through the COGITA web (http://www.gutfeelings.eu/questionnaire/) and as online supplementary material.

Structural properties

Internal consistency of both versions was high (Cronbach’s alpha GFQ-Spa = 0.94 and GFQ-Cat = 0.95). PCA showed one factor with the sense of alarm and the sense of reassurance as two opposites explaining 76% of the total variance for the GFQ-Spa, and 77% for the GFQ-Cat.

Discussion

Main findings

This study has allowed obtaining Spanish and Catalan versions of the GFQ. At this moment, the GFQ is the exclusive measurement tool available to determine the presence of gut feelings of alarm or reassurance in family medicine consultations. The linguistic validation into Spanish and Catalan will allow to expand the research on gut feelings into the Spanish and Catalan speaking regions and to compare their diagnostic value across different health systems.

Literature comparisons

Internal consistency was high for both the Spanish and the Catalan versions (Cronbach’s alpha 0.94 and 0.95 respectively) [Citation4]. The original GFQ achieved Cronbach’s alpha (0.91) and PCA (70.2%) results comparable to the Spanish and Catalan versions [Citation4]. Values for Cronbach’s alpha over 0.7 have been considered acceptable, and values over 0.9 are desirable for clinical application of a questionnaire [Citation9].

Strengths and limitations

Among the limitations of the validation, it should be pointed out the lack of a Delphi procedure with Spanish and Catalan speakers GPs for determining the content validity. In the Methods section, we have discussed the reasons for not doing a Delphi procedure. Considering the participation in our study of GPs from nine different Spanish-speaking countries and two Catalan-speaking regions, the validated GFQ can be used in Spanish and Catalan-speaking countries.

Implications

The next step could be to establish the predictive values of GF for serious diseases in primary care. There is an already finished study aiming to define the diagnostic accuracy of the sense of alarm measured with the GFQ when applied to dyspnoea and thoracic pain [Citation10]. Another study has been designed to assess the accuracy of gut feelings measured with the GFQ in the diagnostics of cancer and other serious diseases in a Spanish primary care setting.

The Spanish and Catalan GFQ could allow research on gut feelings among over 400 million Spanish speakers in more than 20 countries and 10 millions of Catalan speakers in four countries. Researchers interested in translating the GFQ into other languages can use the standardized procedure described in our study and previous translation procedures.

The GFQ can be used in the field of medical education, helping trainers and teachers to explain the existence of an intuitive approach in the decision-making process. Decision-making is the result of the continuous interaction of analytical and intuitive processes. Analytical reasoning and intuitive reasoning check each other’s outcome until a final decision is made. The GFQ can also be used to increase medical students’ and GP-trainees’ awareness of their gut feelings and to learn how to refine and use them. Researchers interested in developing some of these lines of research would be welcomed in the COGITA group (http://www.gutfeelings.eu/contact/).

Conclusion

We have obtained Spanish and Catalan versions of the gut feeling questionnaire, which do not differ from the original one regarding content and reliability.

Gut feelings questionnaire

Download PDF (33.3 KB)Qüestionari de Pressentiments

Download PDF (26.7 KB)Cuestionario de corazonadas

Download PDF (27.6 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors thank Eugenia Carandell, Sara Davies, Gabriel Moragues, Ignacio Ram ırez, Bartomeu Riera, Christian Ruiz, Paloma S. Montes, Alfonso Villegas, and Christopher Yates for their invaluable help during the process. The authors also thank all the Spanish and Latin American GPs who helped with their useful comments; and the Balearic Cancer League (AECC-Baleares) for their support.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Stolper E, Van Royen P, Van de Wiel M, et al. Consensus on gut feelings in general practice. BMC Fam Pract. 2009;10:66.

- Le Reste J-Y, Coppens M, Barais M, et al. The transculturality of ‘gut feelings’. Results from a French Delphi consensus survey. Eur J Gen Pract. 2013;19:237–243.

- Oliva B, March S, Gadea C, et al. Gut feelings in the diagnostic process of Spanish GPs: a focus group study. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e012847.

- Stolper CF, Van de Wiel MWJ, De Vet HCW, et al. Family physicians’ diagnostic gut feelings are measurable: construct validation of a questionnaire. BMC Fam Pract. 2013;14:1.

- Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, et al. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25:3186–3191.

- Barais M, Hauswaldt J, Hausmann D, et al. The linguistic validation of the gut feelings questionnaire in three European languages. BMC Fam Pract. 2017;18:54.

- Report of the COGITA meeting in Riga 2017. [cited 2018 July 11]. Available from: www.gutfeelings.eu/2017/05/22/report-of-the-cogita-meeting-in-riga-2017/

- Stolper E, van Bokhoven M, Houben P, et al. The diagnostic role of gut feelings in general practice. A focus group study of the concept and its determinants. BMC Fam Pract. 2009;10:17.

- Bland JM, Altman DG. Cronbach’s alpha. BMJ. 1997;314:572.

- Barais M, Barraine P, Scouarnec F, et al. The accuracy of the general practitioner’s sense of alarm when confronted with dyspnoea and/or thoracic pain: protocol for a prospective observational study. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e006810–e006810.