Abstract

Background

The introduction of portable and pocket ultrasound scanners has potentiated the use of ultrasound in primary care, whose many applications have been studied, analyzed and collected in the literature. However, its use is heterogeneous in Europe and there is a lack of guidelines on the necessary training and skills.

Objectives

To identify the fundamental applications and indications of ultrasound for family physicians, the necessary knowledge and skills, and the definition of a framework of academic and pragmatic training for the development of these competencies.

Methods

A modified 3-round Delphi study was carried out in Catalonia, with the participation of 65 family physicians experts in ultrasound. The study was carried out over six months (from September 2020 to February 2021). The indications of ultrasound for family physicians were agreed (the > = 75th percentile was considered) and prioritised, as was the necessary training plan.

Results

The ultrasound applications in primary care were classified into seven main categories. For each application, the main indications (according to reason for consultation) in primary care were specified. A progressive training plan was developed, characterised by five levels of competence: A (principles of ultrasound and management of ultrasound scanners); B (basic normal ultrasound anatomy); C (advanced normal ultrasound anatomy); D (pathologic ultrasound, description of pathological images and diagnostic orientation); E (practical skills under conditions of routine clinical practice).

Conclusion

Training family physicians in ultrasound may consider seven main applications and indications. The proposed training plan establishes five different levels of competencies until skill in real clinical practice is achieved.

KEY MESSAGES

The list of ultrasound applications in primary care may be widely extensive.

Ultrasound training for family physicians should cover clinical knowledge, practical skills in the use of ultrasound scanners and practice options.

This paper establishes a framework of applications, skills and a training point-of-care ultrasound plan.

Introduction

The development in recent decades of portable and pocket ultrasound scanners has allowed the point-of-care application of ultrasound, both in physicians’ offices and in the home [Citation1], making it an accessible tool for family physicians.

A systematic review of the applications of point-of-care ultrasound in primary care, published in January 2019 [Citation2], concluded that the precision with which family physicians perform ultrasounds was good in quality studies but also emphasised the importance of training and the disparity of criteria on this point, with wide variations in the duration and type of training received.

There are wide variations in the use of point-of-care ultrasound between European countries [Citation3]. The expansion and introduction of ultrasound into the regular practice of family physicians is already a reality in some European countries while in others, it is still a project in development or an isolated, one-off event.

The ultrasound performed by the family physician should be contextualised in a clinical setting, accompanied by a history and physical examination, and often aimed at answering a specific clinical question [Citation4]. Given the broad spectrum of competencies and tasks performed by family physicians, the ultrasound applications are multiple and varied. Its claimed benefits are limited not only to completing a diagnosis but may also allow risk stratification, ruling out other diagnoses or associated complications, guiding therapeutic decisions, monitoring the response to treatment, serving as a guide for punctures, and screening for some diseases [Citation5].

At the same time, the provision of ultrasound scanners in primary care should be accompanied by thorough, accredited training of professionals. Some specialty programmes include the training of the resident family physician in ultrasound-related competencies, especially in U.S. teaching units [Citation6,Citation7]. However, ultrasound training should be available not only for residents but also for senior specialists. Training may lead to a change in clinical practice and a more remarkable ability to solve ongoing health problems [Citation8].

This study aimed to identify the fundamental applications of ultrasound for family physicians, the necessary knowledge and skills, and the definition of a framework of academic and pragmatic training for developing these competencies.

Methods

This study was conducted in Catalonia, Spain from September 2020 to February 2021. A literature review was carried out, and the ultrasound applications in primary care were listed [Citation2,Citation4]. Through a modified (includes a joint committee between first and second rounds) 3-round Delphi study, the indications of ultrasound for the family physician and the training plan were agreed and prioritised. All family physicians participating in the Delphi study were members of the ultrasound group of Catalan Society of Family and Community Medicine. Procedure and rounds:

Exploratory round: 65 Spanish family physicians trained in clinical ultrasound who routinely use it in their primary care centre. Objective: select the applications considered fundamental from the list obtained from the literature review.

First round (core group): 15 family physicians (all belonging to the first group of 65) with accredited experience in ultrasound of more than five years from different primary care centres and with sustained use of ultrasound in the office. Objective: classification of applications and discussion about training requirements.

Second round (core group): agreement on the final list of applications and training process. Objective: establish the final document.

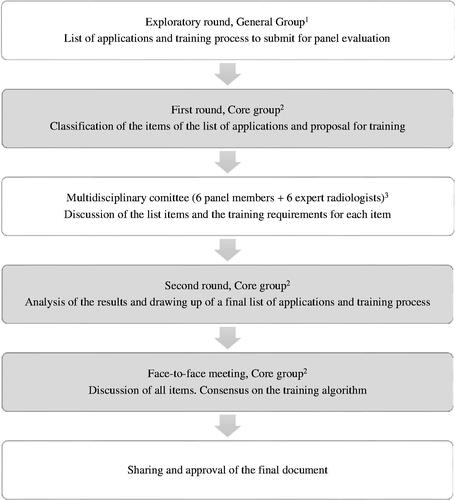

Between the first and second rounds, results were discussed in a joint committee composed of six family physicians and six radiologists. shows the diagram followed in the process.

Figure 1. Process flowchart. 1General Group, 65 family physicians from the ultrasound group of the Catalan Society of Family and Community Medicine who daily perform ultrasound in their clinical practice; 2Core group, 15 family physicians expert in the use of ultrasound, also belonging to the exploratory round group; 36 members of the core group and 6 radiologists who daily perform ultrasound.

For the development of the training plan, international recommendations from various specialties on the evaluation of competencies in ultrasound [Citation9] were taken into consideration. The competencies agreed in the Delphi study were: (1) indication of ultrasound, (2) knowledge of the ultrasound scanners, (3) image optimisation, (4) systematic examination, (5) image interpretation, (6) ultrasound recording and documentation, and (7) clinical decision making. According to these competencies, a training plan was designed by seeking consensus on the number of hours needed to acquire these skills on each of the applications. It should be considered that these are the minimum hours necessary to establish the learner’s autonomy and continuous training and consulting programmes that guarantee the quality and safety of the patient are required. When the minimum training hours are completed, an exam may accredit the corresponding level of competence.

The results of the Delphi study were analysed with descriptive statistics using the R program version 3.6.1 for Windows. In each round, the ≥75th percentile was considered to assess consensus.

Results

Applications

The Delphi study identified seven main ultrasound applications in primary care (). For each application, different structures to be evaluated raised consensus ().

Table 1. Main applications of ultrasound in primary care.

Indications

shows the agreed main indications of ultrasound in primary care according to reason for consultation. The indications also contemplated the ultrasound use to guide different procedures.

Table 2. Indications of ultrasound in Primary Care according to reason of consultation, within the different areas of knowledge and competencies.

Training plan

The Delphi study established five levels of competencies (from A to E), and described the expected skills at each level. shows the fundamental structure of the training plan, which is progressive. To accede to each level of competence, the previous levels must have been accredited.

Table 3. Progressive plan for training in ultrasound in Primary Care.

The minimum number of hours required to accredit the training is shown in .

Table 4. Minimum number of hours needed to qualify for accreditation of each level of competence.

Discussion

Main findings

This document includes the consensus recommendations of the ultrasound group of the Catalan Society of Family and Community Medicine, on the use of ultrasound in all areas of care of family physicians. This Delphi study establishes a framework of applications and skills and a training plan, which may serve as a guide for training programmes in ultrasound in primary care.

Applications

The list of ultrasound applications in primary care may be widely extended. A 2019 Danish study described two main approaches to ultrasound for the family physician; focused clinical ultrasound (aimed at a specific question) or exploratory examination, in a wide range of applications [Citation26]. In a 2020 Danish study, a group of local experts prioritized 30 very varied examinations [Citation27], ranging from determining bladder volume to trochanteric bursitis. However, most ultrasound examinations performed in primary care are abdominal, and this is where more family physicians have received ultrasound training [Citation28], followed by musculoskeletal and head and neck ultrasound. In our document, seven areas of knowledge were defined, as well as using ultrasound for guiding procedures.

Training plan

For the training plan, although levels of competence are typical for any ultrasound, the hours of training required vary according to the different applications. To the accreditation of competencies, the agreed document for assessing of skills in point-of-care ultrasound can be used as a guide [Citation29]. Levels A and B accredit knowledge, level D both accredits knowledge and assesses the skill needed, while levels C and E specifically accredit skills. Level E requires tutored practice in a clinical environment with real patients. For this, the learner must be supervised in carrying out ultrasound examinations by a tutor with accredited experience in ultrasound, until a pre-established number of scans are reached, with an index of agreement with the tutor of >0.7 [Citation30]. We recommend that the tutor is a family physician and that practice is carried out in real clinical conditions. Training for the most advanced level, which involves real clinical practice, may differ. In some cases, the ideal training environment for some ultrasound skills may be the hospital. At this level of advanced skills, collaboration with other specialities is vital.

Strengths and limitations

The availability of ultrasound in primary care varies widely in Europe. Current scientific evidence and technological progress makes its dissemination advisable requiring an implementation plan that includes a structured and accredited training plan, which guarantees its safe use. In Catalonia, the recent provision of ultrasound scanners in most primary care centres, involved developing a training plan for family physicians. Even though this plan has been developed by consensus of family physicians with expertise in ultrasound, the tremendous territorial variety makes it difficult to establish a common strategy for the implementation of ultrasound in primary care. The different European countries start from very remote situations requiring a specific individualised approach.

Implications

Ultrasound training for family physicians should cover clinical knowledge, practical skills in using ultrasound scanners and various learning and practice options, both through live tutoring and with consults at a distance with radiology services.

In addition to the knowledge and skills of the technique itself, physicians performing ultrasounds must know the physical principles and operation of ultrasounds and their clinical indications, as well as have the ability to record images and videos in the medical record, write an ultrasound report and make clinical decisions using the information obtained. The creation of referral and consulting circuits that provide communication channels with other related specialities and especially radiology, is highly recommended.

Training family physicians should be accompanied by a national strategic plan for implementing ultrasound. It is necessary to consider not only the benefits but also the risks of introducting ultrasound in primary care and establish a quality training system.

Conclusion

Training family physicians in ultrasound may consider seven main applications and indications. The proposed training plan establishes five different levels of competencies until skill in real clinical practice is achieved.

Acknowledgements

This study is endorsed by the Spanish Primary Care Foundation.

Disclosure statement

The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper. All authors belong to the ecoAP workgroup, which is an ultrasound group in Primary Care inside the Catalan Society of Family and Community Medicine. The participation of all the members to the workgroup is voluntary, and free from any relationship with the technological and pharmaceutical industry.

References

- Moore CL, Copel JA. Point-of-care ultrasonography. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(8):749–757.

- Andersen CA, Holden S, Vela J, et al. Point-of-care ultrasound in general practice: a systematic review. Ann Fam Med. 2019;17(1):61–69.

- Mengel-Jørgensen T, Jensen MB. Variation in the use of point-of-care ultrasound in general practice in various European countries. Results of a survey among experts. Eur J Gen Pract. 2016;22(4):274–277.

- Sorensen B, Hunskaar S. Point-of-care ultrasound in primary care: a systematic review of generalist performed point-of-care ultrasound in unselected populations. Ultrasound J. 2019;11(1):31.

- Andersen CA, Brodersen J, Davidsen AS, et al. Use and impact of point-of-care ultrasonography in general practice: a prospective observational study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(9):e037664.

- Hall JWW, Holman H, Barreto TW, et al. Point-of-care ultrasound in family medicine residencies 5-Year update: a CERA study. Fam Med. 2020;52(7):505–511.

- American Academy of Family Physicians. Recommended curriculum guidelines for family medicine residents: point of care ultrasound. AAFP Reprint No 290D. 2016. Available from: https://www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/medical_education_residency/program_directors/Reprint290D_POCUS.pdf.

- Tuvali O, Sadeh R, Kobal S, et al. The long-term effect of short point of care ultrasound course on physicians’ daily practice. PLoS One. 2020;15(11):e0242084.

- Tolsgaard MG, Todsen T, Sorensen JL, et al. International multispecialty consensus on how to evaluate ultrasound competence: a Delphi consensus survey. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e57687.

- Frasure SE, Dearing E, Burke M, et al. Application of point-of-Care ultrasound for family medicine physicians for abdominopelvic and soft tissue assessment. Cureus. 2020;12(8):e9723.

- Esquerrà M, Roura P, Masat T, et al. Abdominal ultrasound: a diagnostic tool within the reach of general practitioners. Aten Primaria. 2012;44(10):576–583.

- Lindgaard K, Riisgaard L. Validation of ultrasound examinations performed by general practitioners. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2017;35(3):256–261.

- Speets AM, Kalmijn S, Hoes AW, et al. Yield of abdominal ultrasound in patients with abdominal pain referred by general practitioners. Eur J Gen Pract. 2006;12(3):135–137.

- Sisó-Almirall A, Kostov B, Navarro M, et al. Abdominal aortic aneurysm screening program using hand-held ultrasound in primary healthcare. PLoS One. 2017;12(4):e0176877.

- Tarrazo JA, Morales JM, Pujol J, et al. Usefulness and reliability of point of care ultrasound in family medicine: focused ultrasound in neck and emergency. Aten Primaria. 2019;51(6):367–379. Spanish.

- Sánchez IM, Ruiz AL, González R, et al. Usefulness and reliability of musculoskeletal point of care ultrasound in family practice (1): Knee, shoulder and enthesis. Aten Primaria. 2018;50(10):629–643. Spanish.

- Sánchez IM, Manso S, Lozano P, et al. Usefulness and reliability of musculoskeletal point of care ultrasound in family practice (2): muscle injuries, osteoarthritis, rheumatological diseases and eco-guided procedures. Aten Primaria. 2019;51(2):105–117. Spanish.

- Gottlieb M, Avila J, Chottiner M, et al. Point-of-care ultrasonography for the diagnosis of skin and soft tissue abscesses: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 2020;76(1):67–77.

- Grau M, Marrugat J, Elosua R. Carotid intima-media thickness in the Spanish population: reference ranges and association with cardiovascular risk factors. Response to related letters. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2013;66(4):327. PMID: 24775635.

- Needleman L, Cronan JJ, Lilly MP, et al. Ultrasound for lower extremity deep venous thrombosis: multidisciplinary recommendations from the society of radiologists in ultrasound consensus conference. Circulation. 2018;137(14):1505–1515.

- Diaz S, Conangla L, Sánchez IM, et al. Usefulness and reliability of point of care ultrasound in family medicine: focused cardiac and lung ultrasound. Aten Primaria. 2019;51(3):172–183. Spanish.

- Conangla L, Domingo M, Lupón J, et al. Lung ultrasound for heart failure diagnosis in primary care. J Card Fail. 2020;26(10):824–831.

- Evangelista A, Galuppo V, Méndez J, et al. Hand-held cardiac ultrasound screening performed by family doctors with remote expert support interpretation. Heart. 2016;102(5):376–382.

- Stengel D, Rademacher G, Ekkernkamp A, et al. Emergency ultrasound-based algorithms for diagnosing blunt abdominal trauma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015(9):CD004446.

- Huang Z, Du S, Qi Y, et al. Effectiveness of ultrasound guidance on intraarticular and periarticular joint injections: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;94(10):775–783.

- Andersen CA, Davidsen AS, Brodersen J, et al. Danish general practitioners have found their own way of using point-of-care ultrasonography in primary care: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2019;20(1):89.

- Løkkegaard T, Todsen T, Nayahangan LJ, et al. Point-of-care ultrasound for general practitioners: a systematic needs assessment. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2020;38(1):3–11.

- Touhami D, Merlo C, Hohmann J, et al. The use of ultrasound in primary care: longitudinal billing and cross-sectional survey study in Switzerland. BMC Fam Pract. 2020;21(1):127.

- Sisó-Almirall A, Guirado Vila P, Martínez Martínez N, et al. Top Eco Classroom: a complete track in clinical ultrasound. 22° World WONCA Congress, Seoul. 2018; [cited 2022 November 17]. Available from: www.wonca2018.com/abstract/pop_abstract_view.kin?event=1&pidx=855.

- Solanes-Cabús M, Pujol-Salud J, Alonso Aliaga J, et al. Inter-rater agreement and reliability among general practitioners an radiologists on ultrasound examinations after specialized training programme. J Prim Health Care Gen. Pract. 2019;18(7):3481.