Abstract

Background

For several decades, medical school graduates’ motivation to specialise in family medicine is decreasing. Therefore, residents in family medicine must be motivated for the profession and finish their residency.

Objectives

Goal of the current study is the development and internal validation of an instrument to measure the residents’ motivation for family medicine, which is based on the self-determination theory: STRength mOtivatioN General practitioner (STRONG).

Methods

We used an existing instrument, the ‘Strength of Motivation for Medical School,’ adapted the 15 items and added a 16th item to make it suitable for residency in family medicine. After a review by experts, the questionnaire was sent to 943 residents of family medicine in Bavaria, Germany, in December 2020. An exploratory factor analysis for the STRONG item scores was carried out. The items were analysed for grouping into subscales by using principal component analysis. Cronbach’s alpha for internal consistency was determined for calculating the reliability of the subscales.

Results

After analysis, the questionnaire appeared to consist of two subscales: ‘Willingness to sacrifice’ (eight items, Cronbach’s alpha is 0.82) and ‘Persuasion’ (five items, Cronbach’s alpha is 0.61). The factor analysis with Promax rotation resulted in two factors explaining 39.6% of the variance. The Cronbach’s alpha of the full scale is 0.73.

Conclusion

Based on the internal validation, the STRONG Instrument appears to have good reliability and internal validity, assuming a two-factor structure. This may therefore be a helpful instrument for measuring the strength of the motivation of (future) family medicine residents.

KEY MESSAGES

STRONG may be a valuable instrument to measure the motivation of (future) residents in family medicine.

One possible application of the instrument is that by measuring motivation at several points during residency, the factors that influence motivation can be identified.

It is recommended to validate this tool also for other countries and contexts.

Introduction

For several decades, the motivation of medical school graduates to specialise in family medicine has been decreasing and in many countries smaller than the demand for general practitioners [Citation1–4]. Moreover, residents in family medicine must be motivated for the profession, which increases the chance that they will finish residency, work in family medicine with pleasure for a long time and continue to work on developing their professional skills throughout their careers [Citation5–7].

A commonly used definition of motivation is ‘Powering people to achieve high levels of performance and overcoming barriers to change’ [Citation8]. Motivation is a feeling that moves people to do something and is related to purposefulness and success [Citation5,Citation9].

The self-determination theory (SDT) argues that motivation is influenced by three psychological needs: autonomy, relatedness and competence. SDT differentiates among more or less autonomous motivation, intrinsic, extrinsic and amotivation [Citation10,Citation11]. Intrinsic motivation reflects engagement in an activity due to inherent interest. It is an autonomous type of motivation. Extrinsic motivation refers to engagement in an activity to obtain outcomes, like to gain rewards or social approval, avoid punishment or comply with external norms. They are considered controlling types of motivation. Motivational regulations have different cognitive, affective and behavioural consequences [Citation10,Citation11].

There is a direct relevance from educational settings to intrinsic and extrinsic motivation [Citation12]. As Kusurkar et al. describe in their review [Citation13], motivation in medical education can be both a dependent and an independent variable. In the function of dependent variable, motivation can be influenced by changes in the curriculum or the learning environment in clinical practice. Motivation as an independent variable can influence students’ learning behaviour and study success [Citation13].

Motivation is a major determinant of the quality of learning, the learning strategies students use, their persistence and performance [Citation8,Citation10,Citation14]. The hypothesis is that motivated students try harder during the lesson, pay more attention and persist more to learn the skills than the less intrinsically motivated students. It confirms that autonomous forms of motivation positively influence performance [Citation10,Citation14].

Several validated questionnaires measure the strength of motivation of medical students [Citation15–17]. This makes it possible, for example, to measure changes in motivation over time or to measure correlations between motivation and other factors, such as empathy or personality traits [Citation11,Citation18,Citation19].

Many studies have investigated factors and motivations impacting the decision to choose specific medical specialties. Motivations may include lifestyle choices, the possibility of private practice, interest in particular diseases, motivation for research or teaching or to gain a higher income. Students’ speciality preferences are influenced mainly by interaction with patients and desire to work in a challenging speciality while less common reasons are high demand for specific health services, the income potential, the workload, prestige or the duration of the residency [Citation16,Citation20,Citation21].

Studies on the motivation for a specialisation generally aim to inventory the students’ or residents’ reasons for a particular choice. These are usually self-designed questionnaires, sometimes supplemented with interviews [Citation2,Citation3,Citation20]. Due to its primarily qualitative nature, these questionnaires cannot be used to measure the strength of motivation.

Goal of the current study therefore is the development and internal validation of an instrument to measure the motivation of residents for family medicine: STRength mOtivatioN General practitioner (STRONG).

Methods

Initial instrument

For the development of the STRONG questionnaire, we have chosen to use an existing instrument as a starting point, namely the SMMS: Strength of Motivation for Medical School [Citation15]. This questionnaire is developed to measure the strength of motivation of medical students for medical school. This instrument based on the Self-Determination Theory by Ryan and Deci [Citation9,Citation12], has shown good psychometric properties. The SMMS-questionnaire consists of 15 items scored on a five-point Likert scale, from ‘strongly disagree’ tot ‘strongly agree’. The higher the score, the stronger the motivation. This instrument consists of three sub-scales: ‘willingness to sacrifice’, ‘readiness to start’ and ‘persistence’. The internal consistency of the three subscales, with each five items, measured by Cronbach’s alpha, ranges from 0.55 to 0.67 [Citation15].

Development STRONG

To stay as close as possible to the original questionnaire, we used the Dutch version of the SMMS. We adapted the 15 items to make them suitable for family medicine residency and added a 16th item. This new questionnaire was translated back and forth from Dutch into German and English by native speakers. The items were then critically reviewed in two rounds by general practitioners involved in residency training (n = 4) and family medicine residents (n = 3). Based on the comments from these panels, the items were slightly edited. The items of the SMMS and the STRONG that we used in this validation study are listed in .

Table 1. Items SMMS and STRONG.

Internal validation

The STRONG questionnaire was sent electronically to 943 family medicine residents in Bavaria, Germany, in December 2020. A reminder was sent two weeks after the original invitation.

For the statistical analyses, the software programme SPSS version 27 was used. An exploratory factor analysis for the STRONG item scores was carried out. The items were analysed for grouping into subscales by using principal component analysis. Cronbach’s alpha for internal consistency was determined for calculating the reliability of the subscales.

Ethical approval

Approval for the study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine of the Technical University of Munich (approval no. 627/19S). The survey was anonymous and voluntary, and all participants gave written consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All residents received information on survey’s nature, purpose and procedure and their right to withhold or revoke their consent at any time.

Results

Of the 943 family medicine residents, 275 completed the questionnaire making a response rate of 29.1%. The gender distribution was 83.3% females and 16.7% males. In the entire research group, 78.3% are women meaning that women are slightly over-represented among the respondents. The average age of the responders was 36.7 years, corresponding to the average age in the whole study group (36.8).

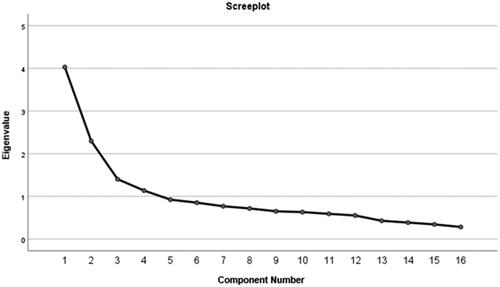

The value of the KMO (Kaiser, Meyer und Olkin) test was .79 and the Bartlett Test resulted in a value of < 0.001, indicating that the data was suitable for a factor analysis [Citation22]. The factor analysis with Promax rotation resulted in two factors (see screeplot – ) explaining 39.6% of the variance [Citation22].

Figure 1. Screeplot of the factor analysis. The x-axis shows the questionnaire items. The y-axis shows the eigenvalues per item.

The questionnaire subscales could be labelled as: ‘Willingness to sacrifice’ (Subscale1) and ‘Persuasion’ (Subscale 2).

Subscale 1: Willingness to sacrifice

This subscale measures to what extent residents are prepared to make sacrifices to become general practitioners. Eight items based on their factor loadings (> 0.40) belonged to this subscale – see [Citation23]. This subscale explained 25.2% of the variance. Although item 2 had a factor loading of only 0.32, we checked the effect of adding this factor on the internal consistency of the subscale. The Cronbach’s alpha of this subscale was 0.82 and decreased to 0.81 when item 2 was added, so we decided to exclude the item from the subscale.

Table 2. Factors loadings of the STRONG items.

Subscale 2: Persuasion

The subscale ‘persuasion’ measures how convinced the residents are of their choice for family medicine. This subscale explained 14.4% of the variance. Four items belonged to this subscale based on the factor loadings of > 0.40 (see ). Although item 4 had a factor loading of only 0.28, we decided to include it into the subscale because it improved the internal consistency of the subscale. Cronbach’s alpha of the subscale was 0.61, which is acceptable.

There were no cross loadings of items in one subscale onto the other subscale with a value of > 0.40. The Cronbach’s alpha for the full scale, with 13 items was 0.73, which is good.

Discussion

Main findings

As far as we know, the STRONG-questionnaire, based on the Self-Determination Theory by Ryan and Deci [Citation9,Citation12], is the only existing instrument for measuring the strength of motivation of residents for family medicine. Based on the internal validation described in this paper, this instrument appears to have good reliability and internal validity, assuming a two-factor structure. The reliability for the ‘willingness to sacrifice’ subscale and ‘persuasion’ subscale are very good (0.82) and acceptable (0.61), respectively. The reliability of the total instrument with 13 items is 0.73.

Comparison SMMS – STRONG

The SMMS, on which the STRONG is based, has three subscales [Citation15]. The questions in the ‘Willingness to sacrifice’ subscale largely overlap with the modified questions on scale 1 in our instrument. Therefore, we have given it the same name. The other questions fit our second subscale. We cannot confidently say why we found two rather than three subscales. The most likely explanation is that it has to do with the different study group (students versus residents) and different content (medicine in general versus family medicine).

Implications of the internal validation

Our study findings mean that the STRONG instrument may be used to measure the strength of the motivation of family medicine residents at different moments during residency: by regularly evaluating the strength of motivation during residency, factors which influence motivation positively or negatively can be identified [Citation13]. This can be done, for example, by measuring the motivation of cohorts of residents over a longer period and seeing how motivation develops. If an apparent increase or decrease can be seen at certain moments, it will be worthwhile to see what possible factors may have contributed. This is especially relevant because in addition to the primary motivation, multiple aspects such as work environment and professional development opportunities, can impact motivation for family medicine [Citation1].

Furthermore, insights into the strength of motivation for the profession are also important later on, as motivation affects the extent to which general practitioners continue to take courses throughout their careers, which increases their employability [Citation24]. To gain insight into the usefulness of this instrument, for example, whether low motivation strengths lead to a higher risk of dropping out, the instrument will have to be used over a longer period. Other possible applications for this tool include calculating the correlation with other factors, such as professional identity formation regarding family medicine or personality traits [Citation25,Citation26]. We do not want to promote using the instrument as a selection tool for family medicine residency or in other situations that may encourage socially desirable responses. The questionnaire has not been validated for selection purposes.

Moreover, this instrument may also be used during medical school, for example, for students considering taking part in a special track that prepares them for family medicine [Citation23]. The validation of this instrument for this group could be done in a follow-up study.

As described earlier, motivation can be more or less intrinsic or extrinsic, with intrinsic and autonomous forms of motivation in particular positively affecting performance and perseverance [Citation8,Citation10,Citation14]. The SMMS, on which our instrument is based, appears to correlate especially positively with intrinsic motivation [Citation15]. A relevant follow-up study is to examine if the same is true for the STRONG.

Strengths and limitations

This study has several limitations. The most significant limitation is the moderate response rate. Because of that, we cannot exclude a selection bias, meaning that more motivated residents may be more inclined to respond. The number of female respondents is slightly higher than the percentage of women among the Bavarian family medicine residents but as the difference is small, it does not affect generalisability. Besides, the sample of this internal validation study only consisted of German residents. Although there are no indications that this target group differs greatly from residents in family medicine in other countries, it is recommended that the validation study be repeated in several countries and different contexts (for example, with residents in other disciplines) for external validation, supplemented by applying the tool in different contexts to test for feasibility.

Conclusion

Based on the internal validation, the STRONG Instrument appears to have good reliability and internal validity, assuming a two-factor structure. This may therefore be a useful instrument for measuring the strength of the motivation of (future) family medicine residents. Insight into the motivation of family medicine residents may increase the likelihood that they will complete their training and stay in family medicine for a long time.

Ethical approval

Approval for the study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine of the Technical University of Munich (approval no. 627/19 S). The survey was anonymous and voluntary. All students received information on the nature, purpose and procedure of the survey and their right to withhold or revoke their consent at any time.

Consent form

All participants have written Informed Consent prior to the study. All methods were carried out in accordance with Declaration of Helsinki.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dagmar Scheider from KOSTA for sending the questionnaire to the residents.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Data availability statement

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to data protection guidelines of the institution but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- Marchand C, Peckham S. Addressing the crisis of GP recruitment and retention: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2017;67(657):e227–e237.

- Avgerinos ED, Msaouel P, Koussidis GA, et al. Greek medical students’ career choices indicate strong tendency towards specialization and training abroad. Health Policy. 2006;79(1):101–106.

- Roos M, Watson J, Wensing M, et al. Motivation for career choice and job satisfaction of GP trainees and newly qualified GPs across Europe: a seven countries cross-sectional survey. Educ Prim Care. 2014;25(4):202–210.

- Brown RGS, Walker C. Motivation and career-satisfaction in general practice. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1973;23:194.

- Artino AR, La Rochelle JS, Durning SJ. Second-year medical students’ motivational beliefs, emotions, and achievement. Med Educ. 2010;44(12):1203–1212.

- Van der Burgt SME, Kusurkar RA, Wilschut JA, et al. Medical specialists’ basic psychological needs, and motivation for work and lifelong learning: a two-step factor score path analysis. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):1–11.

- Schmit Jongbloed LJ, Schönrock-Adema J, Borleffs JC, et al. Physicians’ job satisfaction in their begin, mid and end career stage. J Hosp Admin. 2016;6(1):1.

- Tohidi H, Jabbari MM. The effects of motivation in education. Proc Soc Behav Sci. 2012;31:820–824.

- Ryan RM, Deci EL. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: classic definitions and new directions. Contemp Educ Psychol. 2000;25(1):54–67.

- Barkoukis V, Taylor I, Chanal J, et al. The relation between student motivation and student grades in physical education: a 3-year investigation. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2014;24(5):e406–e414.

- Kunanitthaworn N, Wongpakaran T, Wongpakaran N, et al. Factors associated with motivation in medical education: a path analysis. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):1–9.

- Ryan RM, Deci EL. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemp Educ Psychol. 2020;55:10186.

- Kusurkar RA, Cate TT, van Asperen M, et al. Motivation as an independent and a dependent variable in medical education: a review of the literature. Med Teach. 2011;33(5):e242–e262.

- Pelaccia T, Viau R. Motivation in medical education. Med Teach. 2017;39(2):136–140.

- Kusurkar R, Croiset G, Kruitwagen C, et al. Validity evidence for the measurement of the strength of motivation for medical school. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2011;16(2):183–195.

- McManus IC, Livingston G, Katona C. The attractions of medicine: the generic motivations of medical school applicants in relation to demography, personality and achievement. BMC Med Educ. 2006;6(1):1–15.

- Schulte-Uentrop L, Cronje JS, Zöllner C, et al. Correlation of medical students’ situational motivation and performance of non-technical skills during simulation-based emergency training. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):351.

- An M, Li L. The strength of motivation for medical school: a three-year longitudinal study. Med Teach. 2021;43:1–6.

- Gonçalves-Pereira M, Loureiro J, Trancas B, et al. Empathy as related to motivations for medicine in a sample of first-year medical students. Psychol Rep. 2013;112(1):73–88.

- Al-Fouzan R, Al-Ajlan S, Marwan Y, et al. Factors affecting future specialty choice among medical students in Kuwait. Med Educ Online. 2012;17(1):19587.

- Gąsiorowski J, Rudowicz E, Safranow K. Motivation towards medical career choice and future career plans of Polish medical students. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2015;20(3):709–725.

- Field A. Discovering statistics using SPSS. 2nd ed. Londen: Sage Publications; 2005.

- Herzog T, Brandhuber T, Barth N, et al. “Beste landpartie allgemeinmedizin” (BeLA). ZFA. 2019;95(9):356. German.

- Peabody MR, Peterson LE, Dai M, et al. Motivation for participation in the American board of family medicine certification program. Fam Med. 2019;51(9):728–736.

- De Lasson L, Just E, Stegeager N, et al. Professional identity formation in the transition from medical school to working life: a qualitative study of group-coaching courses for junior doctors. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16:165.

- Hansen SE, Mathieu SS, Biery N, et al. The emergence of family medicine identity among first-year residents: a qualitative study. Fam Med. 2019;51(5):412–419.