Abstract

This final article in the four-part series focuses on the often neglected yet important role of the public in implementing research in General Practice and Primary Care more broadly. Experience in implementation of findings from research with public engagement in Primary Care has highlighted how partnership working with patients and the public is important in transitioning from ‘what we know’ from the evidence-base to ‘what we do’ in practice. Factors related to Primary Care research that make public engagement important are highlighted e.g. implementing complex interventions, implementing interventions that increase health equity, implementing interventions in countries with different primary healthcare system strengths. Involvement of patients and public can enhance the development of modelling and simulation included in studies on systems modelling for improving health services. We draw on the emerging evidence base to describe public engagement in implementation and offer some guiding principles for engaging with the public in the implementation in General Practice and Primary Care in general. Illustrative case studies are included to support others wishing to offer meaningful engagement in implementing research evidence.

KEY MESSAGES

Patients and the public are essential partners for taking evidence into General Practice services.

This paper presents practical guiding principles to help General Practice stakeholders to navigate the complexity of implementation with the public as central partners

Understanding local context and building and sustaining meaningful relationships are critical for optimising public involvement in implementation

Introduction

Public engagement, as an important requirement in health and care research, has been adopted in major national research organisations and initiatives such as the National Institute for Health and Care Research, UK, and Co-Act in Europe, which also describe public engagement in the dissemination and implementation of research in the later stages of the research cycle [Citation1,Citation2]. An increased emphasis on reporting public engagement has resulted in a growing evidence base on how it can be embedded throughout the research cycle [Citation3]. Implementation, where research evidence is embedded into everyday practice [Citation4], is notoriously messy and is often a neglected stage of the research cycle. The complexities associated with getting evidence into practice mean that public engagement in implementation is a relatively novel and less developed area. Many factors related to Primary Care research make public involvement and engagement important e.g. implementing complex interventions, implementing interventions that target health equity, implementing interventions in countries with different primary healthcare system strength. Effective public engagement in implementation can help to ensure that research evidence (what we know) is translated into practice (what we do) quickly and successfully, ensuring high-quality services for all [Citation5]. Involvement of patients and public can enhance the development of modelling and simulation included in studies on systems modelling for improving health services. However, implementation is not straightforward, and all stakeholders will likely to encounter challenges. Despite this, the benefits of having public contributors central to implementation projects far outweigh the challenges [Citation6]. Public engagement in implementation can be considered as embedded as public engagement in every other stage of the research process. This paper draws on real-world examples to develop key principles for how partnership working with public contributors can be effective in implementation. Practical examples demonstrate how public contributors can be involved in research implementation in the General Practice setting despite the different local healthcare settings.

Implementation is a practical process which draws upon a range of strategies or methods to embed knowledge (in the form of useable innovations) into clinical practice to improve outcomes and quality of care [Citation7]. Implementation is important in reducing research waste and the delay in adopting evidence into practice, known as the ‘evidence-to-practice gap’. An increasing body of implementation literature seeks to address the evidence-to-practice gap, yet there are a plethora of theories, models, frameworks and terminology to navigate [Citation8]. Box 1 provides an overview of key terms used in implementation, illustrated with a practical example of the cough consultation in Primary Care [Citation9].

Challenges in implementing new ways of working include a lack of a good evidence base of effective implementation strategies [Citation10], workforce issues (e.g. attitudes, skills, knowledge, and resistance to change) [Citation11,Citation12], and conflicting drivers and agendas between different stakeholders. All these factors impact on the involvement of public contributors in implementation. A key issue is identifying and agreeing on who is responsible for implementation of research results. It may not be the researcher’s primary responsibility but a knowledge mobilisation practitioner can be perfectly placed to broker research knowledge across boundaries as ‘boundary spanners.’

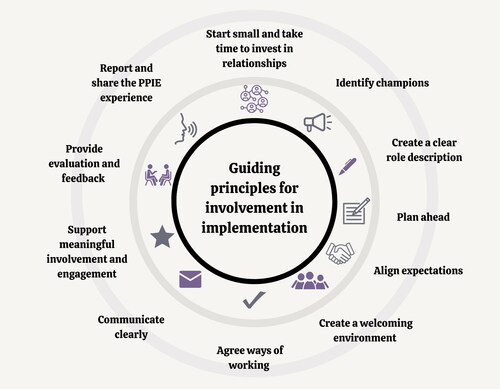

Limited guidance or resources are available to guide implementation stakeholders on how best to involve public contributors as implementers of research in General Practice. As a result, involving public contributors in implementation projects can often be tokenistic with some concerned that public involvement and engagement can increase project costs and that patients or the public might have biased views on specific health issues [Citation13]. Key principles to help to embed public contribution in implementation are proposed in .

Figure 1. Guiding principles for working effectively with patients and the public to implement research into General Practice.

Patient and public networks have been described as an ‘untapped resource’ when implementing research evidence [Citation5]. We have previously demonstrated the emerging role of public contributors as implicit facilitators for mobilising knowledge in implementation practice [Citation14]. Alongside health professionals, they play an important role in optimising implementation and are appropriately positioned to broker and influence both the producers and users of research knowledge [Citation5,Citation15]. Public contributors, therefore, can and should have a role in implementing research evidence to ensure that findings are ready and useable for uptake in Primary Care practice.

Context

Within Primary Care, public contributors are important stakeholders uniquely positioned (as both contributors to and end users of best evidence) to build relationships and better understand local contexts to take opportunities beyond the research into real-world General Practice. A review of reviews on the evidence-to-practice gap in Primary Care identified several effective strategies for closing this gap [Citation16]. Earlier work identified how public contributors generated innovative ideas and solutions to local service problems and catalysed broader change [Citation17]. As implementers, public contributors can help to ensure that end-users have access to information which can lead to a more equal balance of power and better understanding for making decisions regarding their care [Citation14]. However, there is a limited evidence-base to draw on what this looks like and questions remain regarding the role and support required for public involvement and engagement to make meaningful contributions to implementation [Citation10,Citation18].

To optimise public involvement and engagement in implementation and mobilisation of knowledge in General Practice, understanding context and building and sustaining relationships require careful consideration from the outset. Context is a broad concept that concerns ‘weaving together’ of evidence-based practice (e.g. an innovation) with a team, department or organisation [Citation19]. Implementation requires acknowledgement of real-world conditions rather than controlling for them [Citation8], which can help identify strategies to mitigate potential implementation challenges and maximise uptake. For example, a local practitioner will have a good overview of context-specific barriers in their own (working) environment, healthcare setting or local area and, alongside patients and the public, will understand local population needs and context. The context of Primary Care, and more specifically General Practice, will vary between countries and each setting may have a network of public contributors to draw upon (e.g. in the UK many General Practices have a Public Participation Group that work with a range of healthcare professionals to involve the patient voice in shaping services).

Implementation of an innovation, a new way of working, or system change is enhanced by strong relationships and the involvement of all relevant stakeholders, including public engagement, at the outset [Citation20]. Not only is this due to the previously mentioned reasons regarding understanding of context, but building relationships with public contributors and their networks can help to inform decisions and provide support for long-term sustainability. It is also important to recognise that implementation is not a single activity at the end of a project in a linear, staged approach. Implementation is a complex, relational, context-driven approach that requires consideration and planning throughout the research cycle from the outset [Citation21].

The following section outlines examples of how public engagement in implementation has been effective and how public engagement has added value and benefitted an implementation project.

Guiding principles for involving patients and the public in implementation

There is a growing but limited body of literature involving patients and the public in implementation. Yet there are few examples where public involvement has been embedded successfully in implementation in General Practice. This section outlines key guiding principles that can enhance effective involvement of patients and the public to successfully move the benefits of research and other evidence-based practices into Primary Care practice (illustrated in ). Principles are based upon the work of the Keele University Link group: a knowledge mobilisation public contributor group, that grew from Keele’s patient and public involvement and engagement group [Citation22]. This is described further under ‘evaluation’ in the Case Study following.

It is unlikely to need all the components outlined in to succeed. These guiding principles illustrate what can work in practice (e.g. [Citation23]). provides a detailed description of these guiding principles, and the following section demonstrates the practical application of public involvement and engagement in implementation using a completed case study in General Practice as an example.

Table 1. Guiding principles for involving patient and public contributors in implementing research.

Case study

One example of embedded public engagement in the implementation of innovations in General Practice is the Joint Implementation of Osteoarthritis Guidelines Across Western Europe (JIGSAW-E) project based on findings from the Management of OsteoArthritis In Consultations (MOSAICS) study [Citation23]. JIGSAW-E aimed to implement four key innovations from the MOSAICS study across Primary Care in five European countries:

A novel osteoarthritis guidebook

A set of quality indicators

A model consultation in Primary Care

Training of health professionals

Start small, invest in relationships, and identify champions

JIGSAW-E included patients from General Practices from the outset. JIGSAW-E used a cohesive and partnership-focussed Community of Practice (CoP) approach (including patients, clinicians, academics, knowledge mobilisers and project managers) [Citation14] in which public contributors were prioritised and an International Patient Panel was established. Public contributors enjoyed seeing tangible benefits to the communities they represented. In the Netherlands, Patient Research Partners were pleased to see a UK guidebook for osteoarthritis adapted to the Dutch context and actively implemented into practices with GPs and physiotherapists and supported by the Arthritis Foundation.

Create a clear role description, plan ahead and align expectations

The role of public contributors on the International Patient Panel was jointly agreed by the CoP at the start of the project and specific areas for the role of public champions were clarified. They worked with a Knowledge Broker from Keele’s Link Group and local public engagement coordinators on translating, culturally adapting and disseminating the OA guidebook [Citation24].

Payment was offered for their time throughout the project and all expenses were reimbursed.

Create a welcoming environment, agree ways of working and communicate clearly

To facilitate strong communication, the Knowledge Broker and public engagement team developed a glossary of terms in plain language and a guide to acronyms. Plain language summaries of the project were provided. Throughout the project, the Knowledge Broker acted as the dedicated point of contact for Public Contributors and all agreed suggestions were acted upon. They were encouraged by the public engagement leads and a Knowledge Broker to get involved in key knowledge mobilisation activities (e.g. [Citation25]). Additional support and time for questions was provided to public contributors between meetings.

Support meaningful involvement and engagement

Public contributors played a key role in translating complex evidence and recommendations into public-friendly, accessible, and engaging content. Public contributors reminded the team of the importance of creating content in various formats for different demographics and drew on their own varied lived experiences to shape how these were developed.

Provide evaluation and feedback, and report and share the public engagement experience

Teams from across JIGSAW-E were involved in evaluating public engagement and sharing their experiences.

Evaluation was supported by ongoing feedback from the patient panel during the four-year project and shaped how the public could be involved in how the implementation was conducted.

Evaluation of impact of public involvement and engagement in implementation

The Keele Link group assessed their transition into implementation. Using qualitative methods (semi-structured interviews followed by a focus group) the experiences of seven implementers (lay members, healthcare professionals (HCPs), academics, researchers) were explored. Findings highlighted that a conducive environment influenced by an established public engagement team promoted knowledge mobilisation. This team was integral to the selection of the public involvement in implementation. Patient and the public adjusted to and understood the differences between research and implementation. Skills of public members were multi-faceted compromising of experience of conditions, life skills, roles in society and networks (an example of these networks is provided in Supplementary Figure S1). Feedback was important to patients and the public in remaining engaged and feeling confident in questioning ways of overcoming barriers to implementation that they may be in a position to influence.

Implications

JIGSAW-E is an example of well-funded and well-resourced public engagement in implementation, this is not always the case. illustrates a spectrum of examples of engagement in implementation, from small scale local projects to larger collaborations. It shows that even with limited resources, much can be achieved through strong partnership working. Importantly, similarities between key features of and the literature regarding ‘co’-approaches (co-production, co-design, and co-creation) are noted [Citation26]. For example, priorities for successful co-production centre around creating a shared understanding, identifying and meeting the needs of a diverse group of people, balancing power and voice, developing a sense of ownership, and creating trust and confidence [Citation26]. Similar to co-production, it is important to consider all forms of knowledge (including experience and beliefs, not just research) with the patient voice at the forefront and taking local context into account.

Table 2. Description of public involvement in implementation projects and lessons learned.

Public involvement and engagement in implementation takes time and effort and challenges will be encountered. Planning needs to start early, with time and resources set aside to support stakeholders throughout the ‘messiness’ to have a meaningful contribution.

Public contributors remain an under-utilised partner in facilitating successful implementation of research findings into General Practice. We have taken lessons from public engagement in research and applied our understanding to implementation. Core values for partnership working, such as building and maintaining relationships, sharing power, and, establishing mutual ways of working, can help to ensure that public engagement is embedded throughout the research cycle from priority setting research questions through to implementation. Lessons can be learnt from other fields in which patient experiences are used for implementation in Primary Care e.g. in health promotion, individual patient participation as patient experts in patient care or as participants in education.

Conclusion

Public engagement in implementation is important in ensuring that ‘what we know’ from the evidence-base is adopted and embedded ‘what we do’ (in practice) quickly and effectively. The guiding principles presented are intended to help those for whom interventions are intended, to become active partners in enhancing the uptake of research in General Practice services. Further work needs to focus on the accurate and clear reporting of the role of public involvement in implementation to build an evidence base to better understand what works, for whom, and in what contexts.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (115.5 KB)Acknowledgements

To Dr Sue Ashby for her qualitative evaluation of the LINK group and insights and early work into the role of the public in implementation.

The Link Group, Impact Accelerator Unit, Keele University

The JIGSAW-E International Patient Panel

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Box 1. An overview of key terms used in implementation, illustrated by a practical example

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- National Institute for Health and Care Research. Briefing notes for researchers – public involvement in NHS, health and social care research 2021. [cited 2023 Jul 3]. Available from: https://www.nihr.ac.uk/documents/briefing-notes-for-researchers-public-involvement-in-nhs-health-and-social-care-research/27371#how-to-cite-this-guidance

- CoAct. CoAct research cycle 2023. [cited 2023 Jul 3]. Available from: https://coactproject.eu/coact-research-cycle/

- Staniszewska S, Brett J, Simera I, et al. GRIPP2 reporting checklists: tools to improve reporting of patient and public involvement in research. Res Involv Engag. 2017;3(1):13. doi:10.1186/s40900-017-0062-2.

- Proctor EK, Powell BJ, McMillen JC. Implementation strategies: recommendations for specifying and reporting. Implement Sci. 2013;8(1):1. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-8-139.

- Burton C, Rycroft-Malone J. An untapped resource: patient and public involvement in implementation: comment on “knowledge mobilization in healthcare organizations: a view from the resource-based view of the firm.” Int J Health Policy Manage. 2015;4(12):845–847. doi:10.15171/ijhpm.2015.150.

- Rashid A, Thomas V, Shaw T, et al. Patient and public involvement in the development of healthcare guidance: an overview of current methods and future challenges. Patient. 2017;10(3):277–282. doi:10.1007/s40271-016-0206-8.

- Eccles MP, Armstrong D, Baker R, et al. An implementation research agenda. Implement Sci. 2009;4(1):18. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-4-18.

- Davies HT, Powell AE, Nutley SM. Mobilising knowledge to improve UK health care: learning from other countries and other sectors – a multimethod mapping study. Health Serv Deliv Res. 2015;3(27):1–190. doi:10.3310/hsdr03270.

- Francis NA, Phillips R, Wood F, et al. Parents’ and clinicians’ views of an interactive booklet about respiratory tract infections in children: a qualitative process evaluation of the EQUIP randomised controlled trial. BMC Fam Pract. 2013;14(1):182. doi:10.1186/1471-2296-14-182.

- Lau R, Stevenson F, Ong BN, et al. Achieving change in primary care—causes of the evidence to practice gap: systematic reviews of reviews. Implement Sci. 2016;11(1):1.

- Sullivan JL, Adjognon OL, Engle RL, et al. Identifying and overcoming implementation challenges: experience of 59 noninstitutional long-term services and support pilot programs in the veterans health administration. Health Care Manage Rev. 2018;43(3):193–205. doi:10.1097/HMR.0000000000000152.

- Wensing M, Grol R, Grimshaw J. Improving patient care: the implementation of change in health care. Oxford: Wiley; 2020.

- Locock L, Boaz A. Drawing straight lines along blurred boundaries: qualitative research, patient and public involvement in medical research, co-production and co-design. Evid Policy. 2019;15(3):409–421.

- Swaithes L, Dziedzic K, Finney A, et al. Understanding the uptake of a clinical innovation for osteoarthritis in primary care: a qualitative study of knowledge mobilisation using the i-PARIHS framework. Implement Sci. 2020;15(1):1–19. doi:10.1186/s13012-020-01055-2.

- Rycroft-Malone J, Burton C, Wilkinson J, et al. Collective action for knowledge mobilisation: a realist evaluation of the collaborations for leadership in applied health research and care. Health Serv Deliv Res. 2015;3(44):1–166. doi:10.3310/hsdr03440.

- Lau R, Stevenson F, Ong BN, et al. Achieving change in primary care—effectiveness of strategies for improving implementation of complex interventions: systematic review of reviews. BMJ Open. 2015;5(12):e009993. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009993.

- Boaz A, Robert G, Locock L, et al. What patients do and their impact on implementation: an ethnographic study of participatory quality improvement projects in English acute hospitals. J Health Organ Manage. 2016;30(2):258–278. PMID: 27052625. doi:10.1108/JHOM-02-2015-0027.

- Swaithes L, Paskins Z, Quicke JG, et al. Optimising the process of knowledge mobilisation in communities of practice: recommendations from a (multi-method) qualitative study. Implement Sci Commun. 2023;4(1):11. doi:10.1186/s43058-022-00384-1.

- Nilsen P, Bernhardsson S. Context matters in implementation science: a scoping review of determinant frameworks that describe contextual determinants for implementation outcomes. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):189. doi:10.1186/s12913-019-4015-3.

- Rycroft-Malone J, Wilkinson JE, Burton CR, et al. Implementing health research through academic and clinical partnerships: a realistic evaluation of the Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC). Implement Sci. 2011;6(1):1–12. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-6-74.

- Powell A, Davies HT, Nutley SM. Facing the challenges of research‐informed knowledge mobilization: ‘practising what we preach’? Public Admin. 2018;96(1):36–52. doi:10.1111/padm.12365.

- Jinks C, Carter P, Rhodes C, et al. Patient and public involvement in primary care research - an example of ensuring its sustainability. Res Involv Engage. 2016;2:1–1. (doi:10.1186/s40900-016-0015-1.

- Dziedzic KS, Healey EL, Porcheret M, et al. Implementing core NICE guidelines for osteoarthritis in primary care with a model consultation (MOSAICS): a cluster randomised controlled trial. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2018;26(1):43–53. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2017.09.010.

- Schiphof D, Vlieland TV, van Ingen R, et al. Joint implementation of guidelines for osteoarthritis in Western Europe: JIGSAW-E in progress in The Netherlands. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2017;25(1):S414. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2017.02.714.

- Ward V. Why, whose, what and how? A framework for knowledge mobilisers. Evid Policy: J Res Debate Pract. 2017;13(3):477–497. doi:10.1332/174426416X14634763278725.

- Grindell C, Coates E, Croot L, et al. The use of co-production, co-design and co-creation to mobilise knowledge in the management of health conditions: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):877. doi:10.1186/s12913-022-08079-y.

- Vernooij RW, Willson M, Gagliardi AR, the members of the Guidelines International Network Implementation Working Group. Characterizing patient-oriented tools that could be packaged with guidelines to promote self-management and guideline adoption: a meta-review. Implement Sci. 2015;11(1):1–13. doi:10.1186/s13012-016-0419-1.

- Khalil H. Knowledge translation and implementation science: what is the difference? Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2016;14(2):39–40. doi:10.1097/XEB.0000000000000086.

- Araujo de Carvalho I, Beard J, Goodwin J, et al. Knowledge translation framework for ageing and health. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2012. [cited 2023 Jul 26]. Available from: https://www.dcu.ie/sites/default/files/agefriendly/knowledge_translation.pdf

- Langley J, Wolstenholme D, Cooke J. ‘Collective making’ as knowledge mobilisation: the contribution of participatory design in the co-creation of knowledge in healthcare. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):585. doi:10.1186/s12913-018-3397-y.

- Levin B. Thinking about knowledge mobilization: a discussion paper prepared at the request of the Canadian Council on Learning and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council. Canadian Council on Learning. 2008; [cited 2023 Jul 26]. Available from: https://www.oise.utoronto.ca/rspe/UserFiles/File/KM%20paper%20May%20Symposium%20FINAL.pdf

- Currie G, White L. Inter-professional barriers and knowledge brokering in an organizational context: the case of healthcare. Organization Studies. 2012;33(10):1333–1361. doi:10.1177/0170840612457617.

- Eccles MP, Mittman BS. Welcome to implementation science. Implement Sci. 2006;1(1). doi:10.1186/1748-5908-1-1.

- National Institute for Health and Care Research. Guidance on co-producing a research project NIHR Learning for Involvement. 2021. [cited 2023 Jul 23]. Available from: https://www.learningforinvolvement.org.uk/?opportunity=nihr-guidance-on-co-producing-a-research-project

- van den Driest JJ, Schiphof D, Luijsterburg PA, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of duloxetine added to usual care for patients with chronic pain due to hip or knee osteoarthritis: protocol of a pragmatic open-label cluster randomised trial (the DUO trial). BMJ Open. 2017;7(9):e018661. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018661.