Abstract

Background

Increasing numbers of primary care physicians (PCPs) are reducing their working hours. This decline may affect the workforce and the care provided to patients.

Objectives

This scoping review aims to determine the impact of PCPs working part-time on quality of patient care.

Methods

A systematic search was conducted using the databases PubMed, CINAHL, Embase, and the Cochrane Library. Peer-reviewed, original articles with either quantitative, qualitative or mixed methods designs, published after 2000 and written in any language were considered. The search strings combined the two concepts: part-time work and primary care. Studies were included if they examined any effect of PCPs working part-time on quality of patient care.

Results

The initial search resulted in 2,323 unique studies. Abstracts were screened, and information from full texts on the study design, part-time and quality of patient care was extracted. The final dataset included 14 studies utilising data from 1996 onward. The studies suggest that PCPs working part-time may negatively affect patient care, particularly the access and continuity of care domains. Clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction seem mostly unaffected or even improved.

Conclusion

There is evidence of both negative and positive effects of PCPs working part-time on quality of patient care. Approaches that mitigate negative effects of part-time work while maintaining positive effects should be implemented.

KEY MESSAGES

Studies suggest primary care physicians working part-time may negatively affect access and continuity, whereas the quality of medical care and patient satisfaction seem mostly unaffected or improved.

Approaches exist to alleviate the negative effects.

Future research should use a standardised definition of part-time work for comparisons.

Introduction

Increasing numbers of primary care physicians (PCPs) are reducing their work hours. Proposed factors contributing to this development are demographical changes in the workforce such as the increased proportion of female PCPs, and the rise of part-time (PT) work connected to shifting generational interests among younger PCPs from career-oriented perspectives to improved work-life balance [Citation1–3]. Lastly, changes in how primary care is organised may enable this development, as primary care is moving away from PCPs working in full-time (FT) single-handed practices towards more extensive group practices with two or more PT PCPs [Citation4].

'Full-time’ refers to the traditional work schedule of PCPs, typically involving a standard number of hours per week. On the other hand, 'part-time’ encompasses any form of reduced work hours compared to the standard full-time schedule. Considering the changing healthcare landscape, Hodes et al. highlight the complexities of defining full-time work in general practice. The definition of full-time work in the field of general practice has been a subject of debate, as the role of a PCP has become more demanding over time and many PCPs working part-time easily work longer hours than the official definition of FT hours [Citation5].

Not only the workforce itself but also their patients face changes. Timely access to a PCP and continuity of care are both important indicators of quality of care [Citation6,Citation7]. Both indicators are affected if a PCP is only available a reduced number of days per week or a different PCP sees a patient due to reduced availability of their usual PCP. Other domains of the quality of patient care that may be affected by PT work are clinical outcomes, overall patient satisfaction and communication with the patient. The quality of care provided to patients must not suffer because of these developments. Therefore, knowledge of the consequences of PCPs reducing their work hours is vital so approaches mitigating harmful effects can be developed. This scoping review aims to determine the impact of PCPs working PT on quality of patient care.

Methods

To answer our research question, we conducted a scoping review following the guidelines of the PRISMA-ScR checklist (cf. supplementary material). A scoping review was the appropriate study design to support our aim as the heterogenous concept of PT does not allow us to pool quantitative results [Citation8]. This study is a literature review without patient data and, therefore, requires no ethical approval.

Literature search

A systematic search was conducted using the following four databases: PubMed, EMBASE, Cinahl, and the Cochrane Library. The search string used a combination of MeSH terms (for PubMed), Emtree terms (for EMBASE), and free-text terms with Boolean operators. The search strings combined the two concepts PT work and primary care (cf. supplementary material). Finally, a hand search was performed based on the reference lists of selected articles.

Inclusion criteria

Peer-reviewed, original articles with either quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods designs, published after 2000 written in any language were considered for inclusion. Studies were included if they examined any effect of PCPs working PT on quality of patient care, referring to the range of effects and outcomes that can arise when PCPs work part-time. We regarded any reduced (weekly/monthly/yearly) work hours as PT work, regardless of the terminology used by the articles in question. A PCP was understood to be a physician providing primary care, first-contact, accessible, continuous, comprehensive, and coordinated person-focused care as defined by the WHO [Citation9].

Articles were excluded if (1) PT work was not studied as part of the research questions (2) patient impact was not examined (3) primary care was not the setting (4) the full text was unobtainable (5) the article was not a peer-reviewed original article, i.e. comments, opinions, editorials, or 6) there was insufficient information reported in the article to answer our research question.

Selection

We performed a selection in two steps. First, the abstracts and titles of the retrieved publications were screened by the first author (SK). A random sample of 659 abstracts (around 28%) was screened by a second researcher (RT) and an agreement rate of 89% was reached. Discrepancies in the selection choices were discussed among the two researchers and a third researcher was consulted in case of disagreements (SE). Both RT and SE have previous experience undertaking evidence reviews [Citation10,Citation11]. The 75 abstracts the authors disagreed upon consisted of 52 abstracts the second researcher ruled out and 23 papers the second researcher ruled in. The papers were screened manually without utilising any software tools. Second, full texts were reviewed for inclusion by both researchers. None of the 23 abstracts ruled in by the second researcher were included in the final selection.

Data charting

Data from the included articles were abstracted and structured in a table. The table contained the title, first author, year of publication, country of origin, study design, population, and outcomes. This process was performed by the first author and discussed with the other researchers. Finally, we critically appraised the individual articles using the MMAT tool [Citation12]. SK appraised the quality and the results were discussed among the research team to finalise the reporting (cf. supplementary material).

Results

Study selection

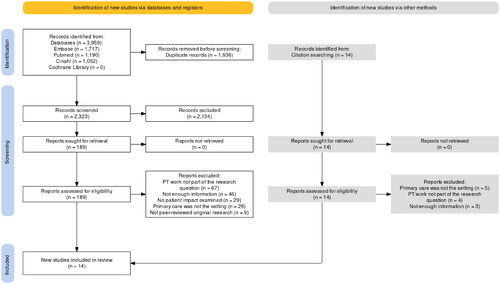

The literature search was performed on 23 March 2023. As shown in , the search identified 2,323 potentially eligible publications after removing duplicates, and 14 additional publications were identified by hand search. After screening titles and abstracts, 203 full texts were assessed and 14 quantitative studies were included for further analysis.

Description of included studies

The included studies were published between 2000 and 2020 and utilised data from 1996 onward (). Eight were conducted in the USA [Citation13–20], one in Canada [Citation21], one in Australia [Citation22], one in Denmark [Citation23], and one in the Netherlands [Citation24]. Two studies were conducted in multiple countries: the first was conducted in 9 European countries [Citation25] and the more recent in 31 European Countries, Canada and New Zealand [Citation26]. Eight studies used questionnaires [Citation15,Citation19,Citation21–23,Citation25,Citation26] or telephone surveys [Citation20] for data collection, one used administrative data [Citation18], and four used a combination of questionnaires and administrative data [Citation13,Citation14,Citation16,Citation17] or practice visits [Citation24]. Three questionnaire-based studies [Citation23–25] used EUROPEP, an internationally standardised measure of patients’ evaluation of care [Citation27] and two [Citation21,Citation26] used data from the QUALICOPC study, a large international cross-sectional study on primary health care performance conducted in 35 countries [Citation28]. All studies addressed community-based PCPs and three additionally considered hospital-based PCPs [Citation13,Citation16,Citation20]. Most studies exclusively investigated general practitioners or family physicians, whereas three studies also included PCPs of other specialities such as paediatrics, internal medicine, and geriatrics [Citation14,Citation15,Citation18].

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies.

The studies’ definitions of PT work varied. Four studies defined PT work as several sessions or weekly work hours below a predefined cut-off [Citation13,Citation15,Citation16,Citation19]. Three studies measured the percentage of a PCP’s full-time equivalent (FTE)[Citation14,Citation17,Citation18] and six studies did not dichotomise between FT and PT status but instead measured weekly work hours as a continuous variable [Citation21–26]. One study differentiated between FT and PT status but did not explain the definition used [Citation20].

Narrative synthesis

Analysis of the studies revealed various outcomes of PT work impacting patient care. These outcomes, i.e. accessibility, continuity of care, clinical outcomes, overall patient satisfaction, and communication, are summarised hereafter.

Accessibility

We found 10 studies determining patients’ ease of access to their PCPs. The studies mostly agreed that a higher FTE was associated with better accessibility. Seven studies supported this finding [Citation13,Citation14,Citation18,Citation21,Citation22,Citation24,Citation25], e.g. by showing that a 10% reduction in weekly work hours resulted in a 12% increase in waiting time [Citation22]. Two studies measured accessibility as a PCP's mean number of days until the third-next available appointment [Citation14,Citation18]. In the study by Panattoni et al. that mean was 3.8 days among PCPs working FT, and 6.2 days among PCPs working 50--60% FTEs [Citation14]. Rosland et al. reported that patients of PT PCPs had less same-day access to their usual PCP than patients of FT PCPs [Citation13]. However, clinic-level same-day access and same-week access to the usual PCP were similar for both patient groups. At the sites studied, patient panels were assigned to teams of one FT PCP, one registered nurse, and one medical assistant. One FT PCP role could be shared among several PT PCPs.

Three questionnaire-based studies found no association between working hours and accessibility [Citation15,Citation23,Citation26]. A Danish study reported that practice characteristics mostly influenced accessibility: PCPs in single-handed practices with short patient lists received more positive evaluations from patients, whereas working hours had no significant effect on perceived accessibility [Citation23].

Continuity of care

We found five studies that measured the continuity of care experienced by patients. Three of these studies found a positive association between weekly work hours and continuity of care [Citation14,Citation23,Citation26]. One study [Citation14] further differentiated between continuity of care provided (which measured the percentage of time PCPs spent seeing their patients) and continuity of care received (which measured patients’ experience). Both measures were positively associated with higher PCP FTE.

Two studies addressing continuity of care found no statistically significant difference between FT and PT PCPs [Citation13,Citation15]. However, PCPs working overtime (more than 65 h per week) were associated with improved continuity. The effect size was relatively small and the authors noted that the organisational structure in which PCPs operated had a five-fold more significant effect on continuity than work hours alone. Further, no group difference was found in the category ‘knowledge of the patient’ [Citation15].

Patient satisfaction

Six studies measured patients’ satisfaction with their PCPs. Four studies found no difference between FT and PT [Citation15–17,Citation19]. In one of the four studies, patients were asked if they would recommend their PCP to a friend [Citation15]. When comparing FT with PT PCPs, no difference was found. However, the proportion of patients who would recommend their PCP was statistically significantly greater among PCPs working overtime (i.e. more than 65 h per week). This was the only study reporting a positive correlation between higher FTE and patient satisfaction.

Two studies found improved patient satisfaction for PT PCPs [Citation14,Citation20]. Haas et al. found that patients of PCPs working PT reported higher overall satisfaction with their health care and their most recent PCP visit. Additionally, patients were more satisfied with these two outcome measures if their PCPs reported a higher professional satisfaction [Citation20].

Three studies used questionnaires answered by patients regarding their opinions on the care they received from their PCPs [Citation23,Citation24,Citation26]. Two of these suggested that patient-reported quality of care increased with work hours [Citation23,Citation26]. An international study found that patients of PCPs working more hours per week reported better comprehensiveness of care, defined as PCPs addressing multiple problems, including personal problems [Citation26]. While Van den Homberg et al. found no statistically significant association between work hours and patient-reported quality of medical care, they identified a powerful association between total PCP time per patient and increased patient-reported quality of medical care [Citation24].

Clinical outcomes

Various measures assessed the clinical outcomes: Two studies used clinical indicators, specifically rates of Pap smear and mammography [Citation16,Citation17], diabetes management [Citation17], and cholesterol measurement [Citation16] to quantify this dimension. One study used 11 indicators (including diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, asthma/COPD, Pap smear, and lifestyle advice) to measure prevention and disease management [Citation24]. One study surveyed PCPs’ satisfaction with the quality of medical care they provided [Citation15].

Most studies found no difference in clinical outcomes associated with work hours [Citation15,Citation16,Citation24]. One report showed a slight increase in quality: After controlling for confounders, PT PCPs had higher rates of Pap smear and mammography (4% higher) and diabetes management (3% higher) [Citation17]. Murray et al. found no statistically significant difference between FT and PT PCPs regarding their satisfaction with the quality of medical care they provided. PCPs working more than 65 h were significantly less satisfied with the time they had for each patient [Citation15].

Communication and the PCP--patient relationship

Only three questionnaire-based studies examined interpersonal aspects of care, such as communication and the relationship between PCPs and their patients. Two studies found positive effects of longer work hours for this domain, reporting better communication, [Citation26] and an improved PCP-patient relationship [Citation23]. One study found no difference between PT and FT PCPs in any interpersonal aspect of care [Citation15].

Discussion

Main findings

We found evidence of undesirable effects of PCPs working PT on quality of patient care: Accessibility was generally shown to be positively associated with longer work hours, and there is also evidence of a similar association for continuity of care. Both accessibility and continuity may not be influenced by PCPs’ working hours alone but also by the organisational characteristics of the practice. Also, communication and the PCP--patient relationship were negatively impacted by PT work.

However, neither clinical outcomes nor patient satisfaction were negatively affected by shorter PCP work hours; several studies showed that PT PCPs performed better in these domains.

Implications on how to maintain the quality of patient care

The framework put forth by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) includes six domains of healthcare quality: Safety, patient-centeredness, timeliness, efficiency, and equity [Citation29]. The domains of safety and effectiveness were most accurately captured by the clinical outcomes examined by the studies included in this review. The clinical outcomes were unaffected [Citation16,Citation24] or improved [Citation17] by all studies using measuring them. This implies that the safety domain is not jeopardised by PCPs reducing their hours. However, no study measured rates of medical errors or clinical outcomes using any form of more objective outcome such as avoidable hospitalisations or hospitalisations for primary care sensitive conditions and it is therefore difficult to draw any more detailed conclusions regarding safety and effectiveness.

The outcome most closely related to timeliness in the review is accessibility. Our results seem to indicate that accessibility as well as continuity of care may suffer when doctors reduce their weekly hours. However, studies also suggested that organisational factors of the practice influence these two dimensions [Citation13,Citation15,Citation23], which implies that practice organisation may hold the key to mitigating the negative effects of reduced working hours. Heje et al. found GPs in single-handed practices received the most positive evaluations regarding accessibility. In contrast a higher number of employees and number of listed patients per GP, and working in a training practice were associated with more negative evaluations [Citation23]. Wensing et al. also supports this finding, with fewer PCPs per practice associated with better patient-reported accessibility [Citation25]. This finding is alarming, as the trend in primary care is moving towards larger practices with several PCPs in many countries. Future research should explore why these particular factors impact accessibility in greater depth. No paper examined the impact of different PCPs, such as practice owners, acting PCPs and PCPs working salary-based. This is unfortunate, as the rise of salary-based PCPs working in group practices may be a significant driving force behind the increasing prevalence of PT work.

Bodenheimer et al. proposed several organisational approaches to improve access and continuity of care [Citation6]. One approach suggests that PT PCPs work more half-days per week instead of fewer but longer days. This change enables PCPs to be available to patients on as many weekdays as possible. Further, continuity and access may be improved through increased usage of alternative communication with patients other than face-to-face visits, such as answering emails every day. Another approach suggested was to create job-sharing arrangements between two PT PCPs. Two PCPs would jointly be responsible for a full panel of patients, so that the same two PCPs would always see a patient. The last approach, i.e. team-based care, was examined by Rosland et al. [Citation13], who showed that same-day access to a patient’s usual PCP was worse if the PCP worked PT but that clinic same-day access to a PCP remained unaffected. For some patients, continuity of care is more critical than for others. In single, acute problems continuity is less important than in longer episodes of care involving chronic illness and multimorbidity. The latter type of health problem often involves plannable care. As it is policy in some practices, if you want to see a GP today or tomorrow, we will decide who you’ll see and if the consultation can be planned, you can see the PCP of your choice. It should be noted that the physicians in a practice and the composition and size of the whole team determine accessibility. Interestingly, Paré-Plante et al. found that the presence of nurses offering primary care services in the practice did not improve accessibility [Citation21].

Despite reduced access and continuity, PT PCPs seem to achieve an equal or even better patient experience [Citation14,Citation15]. This relates strongly to the domain of patient-centeredness. Murray et al. hypothesised that one explanation may be that PT PCPs take on smaller patient panels, thereby increasing the time and energy available for each patient. The study reported that PCPs working more than 65 h weekly were significantly less satisfied with the time they spent with each patient, which supports this theory. However, studies need to directly investigate whether this is the case. This theory could be relevant, as Homberg et al. found a robust correlation between the time PCPs had for each patient and the patient’s perceived quality of care [Citation24]. Further, patient-reported quality of care is influenced by PCPs’ professional satisfaction, as demonstrated by Schäfer and colleagues [Citation26]. PCPs’ job satisfaction was found to be higher for PT PCPs [Citation19] and was shown to be directly associated with patient satisfaction [Citation20]. As this review found several positive effects of PT work, approaches should be developed which mitigate adverse effects while preserving or increasing the positive effects.

Notably, eight out of the fourteen included studies, were published between 2000 and 2009. In contemporary societies, including the field of medicine, working PT is becoming increasingly normalised, which may affect how patients perceive and evaluate PT work in primary care settings.

A 2018 scoping review of the Norwegian Institute of Public Health focusing on effects and experiences of PT work in the health- and community-care services found that studies in the review were very heterogeneous hampered any attempt to pool or compare results. The authors conclude that future research would benefit from a standardised definition of PT work [Citation30]. The comparability issue was also found in our review. Eight of the included studies were performed in the USA with primary care systems that are not comparable to European ones. For example, the study by Rosland et al. was set in two large sites with 68 PCPs that cater exclusively to veterans, to which there is no equivalent in Europe [Citation13]. Further, the average size of practices not only differs between Europe and the USA but also between individual European countries. Finally, the lack of a standardised definition of FT and PT hours means that several weekly work hours, which passes as FT work in certain countries is considered PT work in others [Citation26]. There is, therefore, a need to define PT and FT status more clearly and there is a need for more quantitative studies, which are comparable between countries [Citation5]. These issues may also explain why none of the associations examined in the study by Wensing et al. were found consistently across all countries the study was conducted in [Citation25].

Our review did not yield any specific findings related to efficiency and equity. The approaches proposed earlier should be considered to enhance efficiency of practices and the healthcare system.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first review to examine the impact of PCPs working PT on quality of patient care. This scoping review followed the guidelines of the PRISMA-ScR checklist [Citation31]. A thorough search strategy was designed, and four databases were searched. The MMAT documents the high quality of the included studies, except relatively high nonresponse rates in studies using data from extensive multinational surveys and one study employing the validated Press Ganey instrument, which still maintained a response rate comparable to the national average.

One limitation of this study is the wide-ranging understanding of what comprises a PCP. Most European studies shared a similar concept of the ‘general practitioner’ whereas north American studies used terms such as ‘family physician’ or ‘general internist’ and, in some cases, included other specialists. The role PCPs hold in healthcare systems, as well as what procedures and diagnostics are performed by PCSs varies considerably between countries. Further, some studies included community-based PCPs and hospital-based PCPs and a wide range of practice sizes. We did not want to exclude any of these professions as we hypothesise that the underlying mechanisms of PT-induced changes in patient care are similar in all primary care settings. We recognise that the heterogeneity of definitions of PT work did not allow us to pool the quantitative results. Still, we are confident that the scoping review provides a valuable overview and baseline for future research and systematic reviews.

Conclusion

There is evidence of both negative and positive effects of PCPs working part-time on quality of patient care. PCPs working PT does influence quality of patient care, particularly access and continuity of care, which may be negatively affected. The clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction seem mostly unaffected or even improved. Approaches that mitigate negative effects of PT work while maintaining positive effects should be implemented.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (35.7 KB)Supplemental Material

Download PDF (729.5 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Hedden L, Barer ML, Cardiff K, et al. The implications of the feminization of the primary care physician workforce on service supply: a systematic review. Hum Resour Health. 2014;12(1):32. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-12-32.

- Buddeberg-Fischer B, Stamm M, Buddeberg C, et al. The new generation of family physicians - career motivation, life goals and work-life balance. Swiss Medical Weekly. 2008;138:305–312.

- Gisler LB, Bachofner M, Moser-Bucher CN, et al. From practice employee to (co-)owner: young GPs predict their future careers: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Fam Pract. 2017;18(1):12. doi: 10.1186/s12875-017-0591-7.

- Gerber T, Giezendanner S, Zeller A. Measuring workload of Swiss general practice: a five-yearly questionnaire-based survey on general practitioners’ self-reported working activities (2005–2020). Swiss Med Wkly. 2022;152(2526):w30196. doi: 10.4414/smw.2022.w30196.

- Hodes S, Hussain S, Panja A, et al. When part time means full time: the GP paradox. BMJ. 2022;377:o1271. doi: 10.1136/bmj.o1271.

- Bodenheimer T, Haq C, Lehmann W. Continuity and access in the era of Part-Time practice. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(4):359–360. doi: 10.1370/afm.2267.

- Van Walraven C, Oake N, Jennings A, et al. The association between continuity of care and outcomes: a systematic and critical review. J Eval Clin Pract. 2010;16(5):947–956. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2009.01235.x.

- Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, et al. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):143. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x.

- Primary care. [Internet]. [cited 2023 Jul 5]. Available from: https://www.who.int/teams/integrated-health-services/clinical-services-and-systems/primary-care.

- Tomaschek R, Lampart P, Scheel-Sailer A, et al. Improvement strategies for the challenging collaboration of general practitioners and specialists for patients with complex chronic conditions: a scoping review. Int J Integr Care. 2022;22(3):4. doi: 10.5334/ijic.5970.

- Cody R, Gysin S, Merlo C, et al. Complexity as a factor for task allocation among general practitioners and nurse practitioners: a narrative review. BMC Fam Pract. 2020;21(1):38. doi: 10.1186/s12875-020-1089-2.

- Hong QN, Pluye P, Fàbregues S, et al. Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), version 2018. Registration of Copyright (#1148552), Canadian Intellectual Property Office, Industry Canada. MMAT_2018_criteria-manual_2018-08-01_ENG.pdf. [Internet]. [cited 2023 Jul 5]. Available from: http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/127916259/MMAT_2018_criteria-manual_2018-08-01_ENG.pdf.

- Rosland A-M, Krein SL, Kim HM, et al. Measuring patient-centered medical home access and continuity in clinics with part-time clinicians. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21:e320-328.

- Panattoni L, Stone A, Chung S, et al. Patients report better satisfaction with part-time primary care physicians, despite less continuity of care and access. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(3):327–333. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-3104-6.

- Murray A, Safran DG, Rogers WH, et al. Part-time physicians. Physician workload and patient-based assessments of primary care performance. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9(4):327–332. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.4.327.

- Fairchild DG, McLoughlin KS, Gharib S, et al. Productivity, quality, and patient satisfaction: comparison of part-time and full-time primary care physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(10):663–667. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.01111.x.

- Parkerton PH, Wagner EH, Smith DG, et al. Effect of part-time practice on patient outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(9):717–724. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20401.x.

- Margolius D, Gunzler D, Hopkins M, et al. Panel size, clinician time in clinic, and access to appointments. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(6):546–548. doi: 10.1370/afm.2313.

- Mechaber HF, Levine RB, Manwell LB, et al. Part-time physicians…prevalent, connected, and satisfied. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(3):300–303. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0514-3.

- Haas JS, Cook EF, Puopolo AL, et al. Is the professional satisfaction of general internists associated with patient satisfaction? J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(2):122–128. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.02219.x.

- Paré-Plante A-A, Boivin A, Berbiche D, et al. Primary health care organizational characteristics associated with better accessibility: data from the QUALICO-PC survey in Quebec. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19(1):188. doi: 10.1186/s12875-018-0871-x.

- Swami M, Gravelle H, Scott A, et al. Hours worked by general practitioners and waiting times for primary care. Health Econ. 2018;27(10):1513–1532. doi: 10.1002/hec.3782.

- Heje HN, Vedsted P, Sokolowski I, et al. Doctor and practice characteristics associated with differences in patient evaluations of general practice. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7(1):46. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-7-46.

- van den Hombergh P, Künzi B, Elwyn G, et al. High workload and job stress are associated with lower practice performance in general practice: an observational study in 239 general practices in The Netherlands. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9(1):118. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-118.

- Wensing M, Vedsted P, Kersnik J, et al. Patient satisfaction with availability of general practice: an international comparison. Int J Qual Health Care. 2002;14(2):111–118. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.intqhc.a002597.

- Schäfer WLA, van den Berg MJ, Groenewegen PP. The association between the workload of general practitioners and patient experiences with care: results of a cross-sectional study in 33 countries. Hum Resour Health. 2020;18(1):76. doi: 10.1186/s12960-020-00520-9.

- EUROPEP Patientenbefragungen. [Internet]. [cited 2023 Feb 3]. Available from: https://www.aqua-institut.de/projekte/europep-patientenbefragungen.

- Schäfer WL, Boerma WG, Kringos DS, et al. QUALICOPC, a multi-country study evaluating quality, costs and equity in primary care. BMC Fam Pract. 2011;12(1):115. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-12-115.

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. [Internet]. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2001. [cited 2023 Jul 5]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK222274/.

- Gerd FM. Effects and experiences of part-time work in the health- and community-care services [Internet]. Norwegian Institute of Public Health; 2019. [cited 2023 Jul 6]. Available from: https://www.fhi.no/en/publ/2019/Effects-and-experiences-of-part-time-work-in-the-health-and-community-care-services/.

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850.